13,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

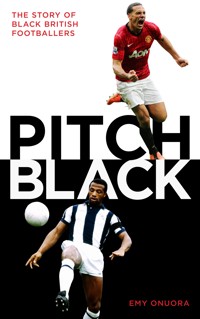

When Paul Canoville took to the pitch for Chelsea in 1982, he was prepared for abuse. When the monkey chanting and the banana throwing started, he wasn't surprised. He wasn't prepared, however, for the abuse to be coming from his own side. Canoville was the only member of the team whose name was booed instead of cheered, the only player whose kit wasn't sponsored. He received razor blades in the post. He took to waiting two or three hours to leave the ground after a match, fearing for his safety. So minimal was the presence of black players in the game, the few who managed to break through were subjected to the most graphic abuse from all sides. Today, 30 per cent of English professional footballers are black, and amongst their number are some of the biggest heroes of the beautiful game. But just how far have we come? With unprecedented access to current and former players ranging from Viv Anderson to Cyrille Regis to John Barnes, Emy Onuora charts the revolutionary changes that have taken place both on and off the pitch, and argues that the battleground has shifted from the stands to the board room. In this fascinating new book, Onuora critically scrutinises the attitudes of FIFA, the FA and the media over the last half-century, and asks what is being done to combat the subtler forms of racism that undeniably persist even today. Featuring startling revelations from all levels of the footballing fraternity, Pitch Black takes a frank and controversial look at the history of the world's most popular sport - and its future.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

To Niki Eltringham, Lloyd, Sean, Amaka, Anayo and Lota, without whom I’d never have got to this place

CONTENTS

PREFACE

IT’S A FREEZING cold January afternoon and it’s a third-round FA Cup tie. The atmosphere is that combination of euphoria and cockiness you get when your team’s comfortably ahead and the opposition are just going through the motions. Mixed in with that cheery, swaggering arrogance is anticipation. Anticipation that at any time you might get another goal to really drive home your dominance. Familiar songs are sung in homage to our heroes. It’s like New Year’s Eve.

The opposition make a change. It’s not made with any conviction that things can be turned around, but just to give the substitute a run-out. As the sub does the familiar handshake with his departing teammate and runs onto the pitch, passing on instructions and tactical changes, the party atmosphere suddenly changes, as if he’s said something loud and offensive to the host. For the final ten minutes or so, the focus of the crowd is on this one player. All the singing has stopped and the cheery atmosphere dissipates into a sea of bitterness and hatred. They can’t wait for him to get possession so they can have their few seconds of vitriol. Every touch, every pass, there’s no let-up. The player himself seems not exactly oblivious – how could he be, such is the noise? – but seems determined to concentrate on the job in hand. He plays gamely, but doesn’t really have any effect on the rest of his teammates, who just want the match to end. The final whistle goes and he retreats to the dressing room with his teammates, pausing to shake hands with home team players. The player in question is an eighteen-year-old striker called Garth Crooks. I was in the crowd that day and was just eleven years old. It was the first time I’d ever really thought about an opposition player. I kept wondering, what must he really be thinking? Did he want to jump into the crowd and take them all on, Bruce Lee-style? What would I have done if he had? Would I have joined in with him? Could the two of us have taken on every one of the 40,000-odd people in the crowd together? The significance of that event for me as an eleven-year-old football fan has led – in a roundabout way, and several years later – to the writing of this book. I’d seen black players before, on Match of the Day and the regional football programmes that ITV showed on Sunday afternoons. I was interested in them, of course – their relative scarcity gave them a kind of novelty value – but something had changed after I thought about Garth Crooks, and I began to develop an enduring empathy with all black players. I wanted to know what they really thought.

Throughout the 1970s, when Crooks was making his name as a slippery, predatory striker, the nature and level of racism that existed within the professional game was at a level that exceeded anything seen today in southern or eastern Europe. Black players were routinely subjected to the most vile racist abuse imaginable. From the terraces, black players were routinely subjected to monkey noises and racist chanting.

Bananas were thrown at them; they were spat at and received death threats. Far-right groups openly sold racist literature both inside and outside football grounds without opposition or condemnation from clubs. Terrace abuse wasn’t solely confined to away fans, either. Home fans abused their own black players mercilessly and sent letters to clubs and the local press, vehemently condemning decisions to include black players in teams.

On the pitch there was often no hiding place from the abuse that black players suffered. Routine racist abuse from opponents was commonplace, as was abuse from teammates in dressing rooms and training grounds.

Racist myths steeped in historical justifications for slavery, colonialism and racial discrimination were widespread. Black players were admired for their strength, speed and flair, but also denigrated for their lack of intelligence, application and courage and their inability to play in cold weather. Coaches and managers ascribed these popular myths to players under their charge and stereotyped their ability and performances.

The FA, as the governing body of the English game, and its Scottish and Welsh counterparts were complicit in all this by their refusal to take action or provide even the most cursory of condemnation – that is, until they were forced by pressure from grassroots anti-racist campaigns to take a stand and provide some semblance of leadership.

The media blindly peddled the same racist myths without either disapproval or qualification and often ignored some of the nastiest examples of racism, so they were tacitly and overtly complicit in the racism that was raging around the game. Black players were routinely described as ‘black pearls’ or ‘black gold’ and their achievements described as ‘black magic’.

That image of the game seems like something from a bygone age. Certainly it is a generation away from today’s multi-camera, 24/7, wall-to-wall football coverage. Racist chanting of the massed, four-sides-of-the-ground variety is almost unheard of, at least in English football stadiums, and is curbed by legal statutes and powers against such behaviour. The media is willing to condemn such behaviour in outraged tones, and coaches and fellow professionals are quick to jump to the defence of fellow teammates subjected to these displays of racism. But while overt racism is condemned, racism in more subtle forms remains. There are still few players of Asian origin playing in the professional game, in spite of the widespread popularity of the game within their communities, and there remains a chronic shortage of black coaches and managers.

There are an increasing number of books on issues of race both in sport and in football in general. Phil Vasili’s excellent Colouring Over the White Line (Mainstream Publishing, 2000) provided a well-researched encyclopaedia of black footballers who have played in the British professional game. However, the critical difference between Vasili’s book and this one is that this book serves as a history of black British footballers from the perspective of those footballers themselves, and an analysis of the key events that have shaped the experience of black footballers today. The sometimes angry, moving and humorous testimonies from current and former players demonstrate the strategies they adopted to deal with and respond to the racism they suffered.

However, although Pitch Black differs in approach from Colouring Over the White Line in many other respects, its starting point is the place at which Vasili’s book ends. Colouring Over the White Line provided an overview of the start of an era in which black footballers were beginning to come of age, or ‘exploding into maturity’, as Vasili put it. Vasili’s book supplied evidence of a black presence since the birth of the professional game in England and ended in the 1980s just as a crop of talented young black footballers were starting to make their mark. Pitch Black concentrates specifically on UK-born or -raised players. Therefore, there’s no Thierry Henry or Patrick Vieira. No Shaka Hislop, Lucas Radebe or Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink. Also, because it’s about British-born black players, Republic of Ireland internationals Paul McGrath, Chris Hughton and Terry Phelan don’t feature, even though they were born in west London, east London and Manchester respectively, though Chris Hughton does count as a manager. However, players such as Cyrille Regis, Brendon Batson, Eric Young and John Barnes, all of whom were born outside the UK but were raised in Britain and played at international level for one of the home nations, are featured in these pages.

This book takes an historical approach, beginning in the 1970s and charting the black British presence in the national game, and ending with an assessment of contemporary issues and an analysis of future developments.

The issue of racism in football just doesn’t seem to go away. Every incident brings about a familiar pattern. Denouncement, outrage, soul-searching, finger pointing. The event is analysed from all angles and eventually things move on once the incident has been milked for all its worth, until the next incident and the old familiar circular pattern emerges again. The purpose of this book is two-fold. Firstly, to provide greater understanding of the issues involved and to allow the debate around racism in football to move away from its familiar arguments. Secondly, it’s intended to provide a voice to those at the sharp end of racism in the game, but a voice that goes beyond the familiar knee-jerk responses, articulating a considered, thoughtful analysis of players’ own experiences and their role within the game.

INTRODUCTION

IT IS 12 April 1982. Paul Canoville is warming up on the sidelines getting ready to come on as substitute for Chelsea against Crystal Palace. He is met with a torrent of racist abuse, mainly from his own fans. Monkey chants and cries of ‘Sieg Heil’ rain down from all four sides of the ground. When Canoville replaces his teammate, the abuse becomes louder as he enters the field of play. He is visibly shaken as he runs on to make his debut for Chelsea. He is just twenty years old.

17 June 2007. Nedum Onuoha is playing for England in the UEFA under-21 European Championship against Serbia. He is met with a volley of racist abuse from a large section of Serbian supporters. Onuoha stares and observes the Serbian fans. His head is held high. He appears cocky, arrogant, but above all dignified. He is twenty years old.

At first glance, the different reactions of Canoville and Onuoha may simply be explained by differences in the personalities of the two young men. In reality, enormous changes took place in the intervening twenty-five years that shaped the two players’ responses. Huge strides have been made in British football to eliminate the type of racist abuse suffered by Canoville. These changes reflect growing opposition to overt forms of racism in wider society, which provides a broader context for Onuoha’s reaction to the racism he suffered.

Onuoha would not have been allowed to react that way had he played in Canoville’s era. Almost certainly, he would have received some form of condemnation from within the media and other commentators on the game for making a stand. He may even have received a fine or a ban. Canoville and his contemporaries were expected to take the abuse, say nothing and concentrate on playing football. In Canoville’s time there was no question of support or sympathy; instead, it was expected that these incidents would build a player’s ‘character’. In 2007, the reaction Onuoha received from the media, fellow professionals, football coaches and the FA was overwhelmingly supportive. If only it were always this way.

The story of black British footballers is linked inevitably with post-war immigration to the UK from the West Indies and, to a lesser extent, from west Africa. There has been a consistent black presence within the game in Britain right throughout the professional era. Many notable players were born outside the UK, in British colonies, like the South African Albert Johanneson. Others were from Britain’s black communities, which, prior to the Second World War, were largely atomised and dispersed, with the exception of black communities within British seaports. The post-Second World War migration from the Caribbean and other Commonwealth countries saw black communities settle not in seaports for the most part, but in manufacturing and industrial centres. It was the sons of this generation of migrants who formed the cohort of black players who, by their numbers and endeavours, collectively began to have an impact on the beautiful game throughout the UK.

Of course, there were black professional footballers plying their trade from the beginning of this era. There was the Bermudan Clyde Best at West Ham, who had made his debut for the Hammers at the start of the 1969/70 season. Local boy and pacy winger Johnny Miller played for Ipswich and Norwich from 1968 until 1976 and was in some, albeit limited, circles touted as a possible first black player to play for England. The East End-born Charles brothers, John and Clive, played for West Ham in the early 1970s. But it was a younger group of players, those who first came to prominence in the mid- to late 1970s onwards, whose impact was so significant. This wave of black footballing pioneers, whose presence paved the way for the normalising of a black footballing presence within the British game, differed in two important respects from those who had gone before.

Firstly, those players such as Laurie Cunningham, Cyrille Regis, Viv Anderson, Brendon Batson and others were born or at least raised in the UK and grew up within emerging black communities. The places they grew up in and the schools they attended were mainly based in working-class areas where football was ingrained within the fabric of the community. Football was, and is, extremely popular in the Caribbean and in Africa, where the pioneers of the black professional game in the UK drew their heritage from. A generation of young black boys played football and flourished, building on the game’s appeal within black communities and in working-class sporting culture, which became particularly potent following the success of the 1970 Brazil World Cup side. This multiracial team, with its style and skill and brand of flowing, graceful and above all exciting football, personified by its stars, Pelé and Jairzinho, provided the role models that this generation could follow and emulate.

Secondly, sport was one of the few areas black communities in Britain were actively encouraged to excel in. Black British footballers remain vastly over-represented in the professional game compared to their overall proportion within the general population. Some 20 per cent of professional footballers are black, compared to around 3 per cent of the general population. In the 1970s, the experience of black pupils in schools was characterised by widespread and systematic underachievement and discrimination. Black pupils typically received an educational experience that was distinctly below par, to use a sporting metaphor. In London, where the vast majority of migrants from the West Indies lived, some 70 per cent of pupils in schools for the educationally sub-normal (as students with learning difficulties were then termed) were of West Indian origin, in spite of this group making up only 20 per cent of the overall school population. In addition, school expulsion figures were dominated by children of West Indian origin. Parents of these children consistently complained about the low expectations that teachers had for their sons and daughters, and about the unfair application of discipline and sanctions. Sport often remained the only part of school life where teachers had high expectations and actively nurtured and supported any aspirations these children had.

Therefore, a combination of football’s widespread appeal within black and working-class communities, the encouragement and support for black sporting achievement (largely at the expense of academic study), and the inspiration provided by the all-conquering Brazil side would provide the British game with a pool of footballing talent from within its black communities in excess of the handful of black footballers who had participated in the professional game up to that point.

Black footballers have always reflected the changing styles and fashions of Britain’s black community. George Berry and Vince Hilaire’s afros, Ricky Hill’s ‘wet look’, Les Ferdinand’s ‘flat top’ and Rio and Anton Ferdinand’s cornrows, as well as the young Paul Ince’s quite frankly woeful hairstyle, have provided sources of admiration, amusement and downright disgust amongst black football fans and the wider black community. Black players’ goal celebrations – the high five, the touch, the grip, the bogle, body popping and backslides – all reflected shifts in black popular culture. These symbols were extremely important to black players throughout the 1970s and beyond. In the face of widespread racism within the game, they reflected the solidarity that existed between black players, and their role in helping footballers deal with the racism they suffered on and off the pitch cannot be underestimated.

These ordinary black men from ordinary black communities instantly became role models, pioneers, ambassadors and the focal point for debates around national identity, just at the point at which they got their first foothold in the professional game. Most if not all of the players who feature in this book were ill prepared for the responsibility associated with their new-found status as professional footballers, let alone as role models and pioneers. Many of them managed to live up to the responsibility, but often at a price, both to their dignity and pride, and to their families and close friends. For black communities, an empathy and understanding of their plight, based on often bitter experiences in school, on the streets and in the workplace, is the reason pioneers such as Regis, Barnes and Wright remain extremely popular amongst black football fans regardless of which team they support.

Beyond black communities, the impact of black footballers has played another important role. It provided a glimpse, albeit a narrow one, into the culture of young black Britain. Fashions, hairstyles, musical preferences all provided a lens through which many whites viewed black communities. More importantly, in supporting their heroes who play week in, week out for the teams they support, many white fans took their first steps towards a stand against racism. Football became the arena in which the stupidity and folly of racism was cruelly exposed, and led to a sea change in football grounds around the country. It is the one place that many if not most football fans receive any kind of anti-racist education or challenge to their racist behaviour and it helped to challenge the most overt expressions of racism not only in football but in society as a whole.

Of course, the level of racism suffered by black players in the 1970s and ’80s differs radically from that suffered by black players today. Today, cases are more isolated and less socially acceptable. Official responses to racism within the game are more likely to condemn the racists as a matter of course. Players have been sent off and clubs have been fined where allegations of racial abuse have been confirmed, but there remain deep-rooted problems within the British game. The lack of black coaches at managerial level is an ongoing issue which those responsible for running the game continue to be slow to address. Sympathy is offered and highly qualified black coaches are told to be patient and that their time will come, yet it seems that the number of black managers never rises past three or four, while younger and less-qualified white coaches are given high-profile managerial and coaching positions. In addition, football clubs and the respective Football Associations have done little to bring their considerable influence to bear to protect black footballers in their care and employ from racist abuse and discrimination, particularly when those players are representing their clubs and countries in European competitions.

It would, however, be wrong to define the participation of black footballers solely in terms of racism. The life of a professional footballer is a good one, even a great one. It remains the envy of many small and not-so-small boys and has caused untold heartache to those whose chances to join its ranks have been cruelly denied through bad luck, injury or lack of talent. Even before the Premier League era, when the financial rewards for players, including those of modest ability, became downright insane, it was a very good way to earn a living. Football’s golden age can arguably be traced back to the beginning of the 1960s and the abolition of the £20 per week maximum wage. Even then, it wasn’t until stars like Jimmy Greaves and Denis Law decamped to Italy to earn big money that clubs were forced to pay up in order to head off the potential drain of talent to foreign shores. By the end of the 1960s, George Best was earning £1,000 a week, a staggering leap in wages in comparison to what he might have earned at the beginning of the decade. It was the start of the real disparity between the wages of the average footballer and that of their friends from their communities. This ever increasing disparity was firmly entrenched by the mid-1970s, when black footballers were collectively making their way in the game. In addition to the financial rewards, there was the adulation, the very reasonable working hours, the downtime and the myriad off-field distractions. Footballers have lived the lifestyle and black players have been no different in that respect. However, while the lifestyle of a professional footballer has brought great rewards, both financial and otherwise, the experience of black footballers has been materially different from that of their white counterparts. Although some black players firmly attest that they have not faced racism, or that its impact has been marginal, for the vast majority it has been an important feature of their careers as footballers. For those players, whether they played in the top flight and won international caps or spent their careers in the lower leagues, it is their common experience of racism that forged the solidarity that exists between them and it’s that which makes their stories so compelling.

CHAPTER 1

PRE-THREE DEGREES

‘He was as good as anyone I saw play. As good as Barnes and right up there with George Best. He was the best player I ever played with.’ – Cyrille Regis

IAURENCE PAUL CUNNINGHAM was quite simply one of the most talented players of his generation. Possessed of poise, balance and speed, his movement was graceful, effortless and economic. He glided around the pitch and was blessed with great touch, awareness and an ability to play at his own pace regardless of the topsy-turvy, helter-skelter nature of the game going on around him. In a remarkable career, he was the first English player to play for Real Madrid and the second black player to win a full England cap. He played for Manchester United, won an FA Cup winners’ medal as a prince amongst Wimbledon’s Crazy Gang and, at West Bromwich Albion, he made up one-third of the ‘Three Degrees’, the legendary footballing trio that formed a critical part of the Ron Atkinson side that achieved considerable success throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s. Injuries robbed him of his key footballing faculties while at Real Madrid, and he never fully recovered those key ingredients that made him such a wonderful performer: his easy acceleration and change of pace. While his career declined from its peak of gracing the Bernabéu, the greater tragedy was the cutting short of his life in a car crash at the age of just thirty-three.

English football could be a dire place if open, attractive football was the kind of thing you wanted to watch. Pitches were often devoid of grass and the first shower of rain would quickly turn them into mud baths. Derby County’s Baseball Ground was notorious for being particularly poor. It was covered in several inches of mud throughout autumn and winter, and baked hard in early and late spring as the season drew to a close. Grass seemed to be anathema to the Baseball Ground, as though it were permanently on strike or some grass-based apartheid was at play to prevent it from operating as it should. Coaches valued toughness, grit, determination, work rate and courage over technical ability. Every team seemed to have at least one midfield ‘enforcer’, who possessed little in the way of technical ability but whose job was to intimidate and brutalise the opposition. Central defenders were typically big, tough-tackling and good in the air, but extremely vulnerable to any kind of pace or speed of turn. Full-backs were often of limited technical ability, but were likewise expected to be tough in the tackle. Up front, target men were often cut from the same cloth as their centre-back counterparts and would typically operate alongside a small, nippy, infinitely more mobile partner to form a big-man/little-man strike force. In midfield, players were expected to get stuck in and display a lung-busting work ethic. As a result, the football served up on a weekly basis often lacked guile and quality and was devoid of anything approaching style. Players would often be covered in so much mud the numbers on the backs of their shirts couldn’t be seen. That is not to say that football didn’t possess moments of excitement. There were plenty of goal-mouth incidents and the attritional nature of the football on show, while not aesthetically pleasing, had its own unique beauty of a kind.

There were, of course, exceptions to this. Some teams throughout the leagues had supremely gifted individuals of outstanding technical ability, but they were often mistrusted. Viewed often as ‘Fancy Dan’, maverick types, they were too showy, too ostentatious and over-indulgent for the tastes of all but a few football managers. They were not to be trusted, particularly when the going got tough, and they would often be overlooked at international level. The England national team’s wilderness years throughout the 1970s and early 1980s was attributable to this rigid mindset. Successive England managers would ignore or give limited opportunities to flair players, and then all too readily dispense with their services when, with the team set up in a strict, rigid and functional formation, they inevitably failed to perform.

Laurie Cunningham was one of the game’s aesthetes. In addition to the fluency and grace of his movement, he had an array of tricks, flicks, drag-backs and general ball skills that were simultaneously baffling for defenders and breathtaking for spectators. Traditionally, in-swinging corners were performed by left-footed players from the right-hand side and vice versa. Cunningham took in-swinging corners from the right with the outside of his right foot. He also had two good feet and was a deceptively good header of a ball, but his hallmark was his ability to run with the ball at opposing defences. Picking up the ball from deep, he could turn defenders inside out and, with a drop of the shoulder and a change of pace, could beat them from a standing start.

West Bromwich Albion’s Three Degrees marked a watershed in the development of black professional footballers in the UK. Until the 1970s, black footballers tended to exist as isolated examples. Albion’s larger-than-life manager Ron Atkinson, however, turned the blackness of Cunningham, Cyrille Regis and Brendon Batson into a somewhat crude publicity drive, dubbing them the Three Degrees after the popular black female vocal trio, who were allegedly Prince Charles’s favourite singers.

Atkinson had transformed the fortunes of Albion, and the side had developed into a successful, attractive team. From the beginning of the 1970s, the club had struggled to maintain its First Division status and suffered relegation in 1973. It had gained promotion in 1976 and had performed well, but under Atkinson’s stewardship they began to challenge for trophies and titles. Cunningham, Batson and Regis formed an integral part of the team’s transformation and Albion was the first high-profile club of the era to play so many black players in the same side. The Three Degrees were distinctly of their time.

Regis and Batson were born in the Caribbean and Cunningham was born in north London. Their parents were of the generation that had come to the UK during the postwar period. Many migrated to Britain without any real plans other than finding work and getting settled, and many others came with the intention of staying for a few years and then returning home. Those whose initial plan was to return home often found that employment, settling into a community and, in particular, raising their children in a new country all acted as impediments to their moving back to their countries of birth.

The second generation had a distinctly different attitude to that of their parents, but players such as the Three Degrees learned, in the rarefied atmosphere of English professional football, to adopt some of those characteristics of determination and stoicism that formed a critical part of their parents’ experience. Their parents had faced unparalleled levels of discrimination. Many skilled workers were forced to take jobs several rungs beneath their levels of expertise and competence. Their employment opportunities were characterised by low pay, low status and semi-or unskilled work and they were barred access to promotion, equal pay and often basic employment protection. In housing, the deliberately discriminatory policies applied by local housing authorities and estate agents conspired to consign black communities to the worst housing available, and they suffered discrimination in all other aspects of the social life of Britain, including in shops, pubs and clubs. Racist taunts and abuse in the streets and physical attacks and beatings were a common experience, particularly for young men. Even places of worship were often off-limits for fanatically Christian West Indians, as men of the cloth applied their own rather unique take on Bible teachings of ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’ and politely, and not so politely, refused them admittance to church. Their children, mainly born and raised in the UK and without the perspective of immigrants and new arrivals, were not prepared to put up with the indignities their parents were subjected to, and resisted this treatment in more overt ways. Discriminated against in a range of social spaces, including the streets of their own communities, often by right-wing activity or the police-enforced ‘Sus’ (stop and search) laws, they began to develop both organised and spontaneous forms of resistance.

The Three Degrees were of this generation. All had spent their formative years growing up in London; Cunningham had been born there. Their impact was little short of phenomenal for a number of key reasons. Firstly, they could all play. Regis and Cunningham went on to become full internationals and Batson represented England at B level. Secondly, they were members of a successful side that played free-flowing, attractive football that brought Albion some success before Atkinson departed for Manchester United and the side he had built broke up. Thirdly, as a consequence of the team’s success and their manager’s eye for publicity, the novelty of three black players in a top-flight side at a time when black players were still rare proved to be too good an opportunity to resist for the press, who competed with each other to come up with the most offensive headlines and ways of peddling lazy stereotypes. The final reason was related to the level of hatred and abuse they received during games. At a time when the existence of racist abuse from the terraces often went unreported by match commentators, even when it was evident from Match of the Day or the regional football programmes shown on ITV, the level of venom was such that Granada TV’s Gerald Sinstadt commented on the ‘unsporting’ treatment of the trio by Manchester United supporters in a league game that Albion had won 5–3 at Old Trafford in December 1978. The three had played brilliantly and Cunningham in particular had given United’s defence a torrid afternoon. Uniquely, Sinstadt had commented on their treatment at a time when the media routinely ignored instances of racist abuse towards black players.

However, their impact on the generation of black footballers who aspired to play the game professionally, and those professionals already plying their trade as footballers, would prove to be inspirational. Their contribution marked the point at which the experiences of black players moved from the individual to the collective, more generalised experiences. The Three Degrees marked the point at which any young black professional entering the game knew they could expect to receive torrents of racist abuse, but also knew that, given attitudes within the game, they would be forced to deal with this largely by themselves. It is conceivable that for some black players considering a football career, the poisonous environment in which they had to earn a living would have acted as a serious impediment.

West Ham had been the first top-flight club to field three black players at the same time when Clyde Best, Ade Coker and Clive Charles turned out for the Hammers in April 1972 for a game against Tottenham. Before the mid-1970s, black players had suffered racist abuse to a certain degree, but their involvement in the professional game had been different. They were largely viewed as an exotic novelty act. What changed – and the Three Degrees epitomised this sea change – was the numbers of players coming into the professional game, and the subsequent response from the terraces: a concerted campaign to abuse black players, often involving organised racist groups. Their presence was no longer an anomaly; this was a movement. Viv Anderson was winning titles and European honours under Brian Clough at Nottingham Forest. Tunji Banjo and John Chiedozie were at Orient. Luther Blissett was terrorising defences as part of the Watford team that had a meteoric rise through the divisions to finish as runners-up in the then First Division. George Berry and Bob Hazell formed a tough-tackling, physically intimidating centre-back partnership at Wolves. Garth Crooks was top-scorer for his home town team of Stoke City.

The participation of these players and others was an affront to those who viewed the game as the preserve of whites. For the far right, who used football to promote their ideology and recruit followers, here in microcosm was the expression of the narrative that the country was being, or had been, taken over by blacks, and no area of society was safe, including the game that Britain had given the world.

Laurie Cunningham’s introduction to the professional game was a baptism of fire. Shortly after making his debut, playing for Leyton Orient, Cunningham played against Millwall at their home, the Den, in December 1974. In May of that year, the National Front had achieved 11.5 per cent of the vote in a by-election in the London Borough of Newham and were claiming to have 20,000 members.

In addition to Cunningham, the Orient side included another black player in Bobby Fisher, and an Asian player, Ricky Heppolette. As the team arrived at the Den, they were met by National Front members, distributing racist propaganda. As they emerged from the tunnel and entered onto the pitch, as well as the usual vitriol, they were greeted with bananas and a carving knife that were thrown onto the pitch. Cunningham and Fisher, in imitation of the 1972 US Olympic athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith, made black power salutes as an act of defiance.

The game had given the eighteen-year-old Cunningham a taste of the racial prejudice he would face throughout his career. He also recognised his position as a trailblazer and role model, realising that he couldn’t be seen to allow the abuse to affect him because of the impact it might have on other black players. Cunningham reasoned that if he could find a way of dealing with the abuse and the other forms of racial prejudice he faced, it would be easier for others to get a fair chance. He understood that he was going to need to put up with the intimidatory tackling, not only because he was a young, skilful winger, but also to prove that, as a black player, he possessed the necessary ‘bottle’ – the mental fortitude that casual prejudice dictated was a key trait lacking in black players.

Cunningham was shown remarkable patience by George Petchey, his manager at Orient, who was to remain a friend of Cunningham’s throughout his life. He was a man prepared to go against the popular and often populist ideas about black players. He was not alone in this regard, but few within the game appeared to be prepared to actively challenge conventional wisdom at this stage. The clubs and the FA appeared impotent and unsure as to how to respond, preferring instead to remain silent, with only a few honourable exceptions. Not wholly convinced that football was to be his chosen career, Cunningham was torn between a career as a dancer (he had an offer to join the renowned Ballet Rambert Dance Company) and football. He’d developed a reputation as a somewhat indifferent time-keeper with a penchant for fashion and nightclubs. However, he also displayed a canny sense of the political and social environment in which he lived, and embarked on a political journey in order to make sense of his experiences and those of other people in black communities. Assessing his time as a young professional at Orient, he remarked:

There have been times when I’ve been mixed up about the race thing. A couple of years ago I thought that to be black in England was to be a loser. You know, back of the queue for decent jobs. Suspicion on you before anyone knew what you were about.

He continued:

I did have a feeling for ‘Black Power’. It seemed to meet the mood of frustration. It could give you some pride. Then I changed. It sort of struck me that the great majority of people, black and white, are in the same boat, fighting for a decent living. It also struck me down at Orient I was getting a very good break. I got on well with George Petchey. It didn’t matter to him whether I was black, white or Chinese just as long as I could play.

For Cunningham, the footballer’s lifestyle could elevate him above the economic effects of racism, but couldn’t protect him from its psychological and emotional impact. It’s uncommon for footballers to take a political stance, but Cunningham had one. How could he not, given the harsh realities of racism in the game and wider society?

At the beginning of the 1976/77 season, a singular event encapsulated the tense relationship between the police and the black community, something Cunningham no doubt had in mind when he was analysing the way that black people were treated with suspicion as a matter of course. Two hundred and fifty thousand people had attended the 1975 Notting Hill Carnival, the biggest ever turn-out. Capital Radio had broadcast live from the event, encouraging attendance from across London. The carnival had become Europe’s biggest street event and was being established as a must-attend attraction for people from the black community from London and beyond. Middle-class residents in north Kensington had organised an anti-carnival petition, signed by 500 people in March 1976. Tension rose throughout the spring and summer of 1976 in the run-up to the carnival, and the Metropolitan Police had stated there was to be a heavy presence in response to incidences of pickpocketing the previous year. Three thousand police officers were to be deployed, ten times the numbers from previous years. Pressure was placed on carnival organisers to cancel the event or hold it elsewhere. By the August bank holiday, the scene was set for clashes. Disproportionate and aggressive policing, designed to intimidate or to establish superiority, was met with resistance. In the fighting that followed, 325 police were wounded and sixty people were arrested and charged. Later that day, the police, by way of some kind of poorly conceived vengeance on the black community, arrested eighteen young men in Islington, far away from Notting Hill. These young men were first accused of ‘suspicious behaviour’, then arrested and questioned in custody. While in custody, according to the police accounts, all eighteen young men voluntarily confessed that they had gone to the carnival in order to steal and attack the police. The police case hinged on these ‘confessions’ of these eighteen men, seventeen of whom provided evidence that they had been assaulted in police cells. In spite of the best efforts of the prosecution to secure convictions, the jury came up with forty-three not-guilty verdicts, eight guilty and twenty-eight undecided to the range of charges that had come to court. The media response was, as usual, to back the police version of events, even in the face of the evidence as to how the ‘confessions’ had been obtained; there was nothing by way of media or basic journalistic investigative scrutiny of this event. The incident illustrated not only the tense relationship between black communities and the police but, critically, the media’s attitude to black communities.

The press, particularly the tabloids, were busy demonising black communities and especially black youths, portrayed as criminal, job-stealing, slum-dwelling immigrants rather than the disadvantaged, criminalised and exploited section of British society that, by and large, they were. The press and media in general did not routinely condemn incidences of racism in football until some two decades later and in fact actively contributed to spreading the stereotypes and myths that were routinely ascribed to black footballers.

The era was also a time of increasing activity from the National Front and the British Movement. The far right had first targeted football as potentially fertile ground in the mid-1960s and again made a concerted effort in the 1970s. Far-right literature cynically contained football-related material in a direct attempt to appeal to fans, with Bulldog, the youth paper of the National Front, even having a league table of the most racist fans. While the level of racism in the 1970s was often of a horrific kind, and at clubs where the level of hatred was at its most venomous there existed a significant far-right presence, not all fans who indulged in this behaviour were members of far-right groups. Some indeed were; others had a loose association or alliance; others had no involvement at all but were heavily involved in racist behaviour. Other fans, of course, wanted nothing to do with the behaviour of their fellow travellers. Inevitably, racism coupled with the increase in incidences of football violence turned many off attending games.

There were other developments taking place within the game that were beginning to affect the behaviour of spectators at football matches, too. By the mid-1970s, players’ wages were on the rise, which precipitated an increase in revenue. This increase was, at least amongst the top clubs, paid for by an increase in admission prices. The increases weren’t significant enough to deter the large bulk of supporters, but they had the effect of pricing out supporters at both ends of the supporter age spectrum: pensioners and those of school age no longer attended matches in the numbers they had previously. These two groups generally had a civilising effect on fan behaviour. Older fans – fathers, grandfathers, older relatives – would actively deter bad behaviour, usually by their presence alone. Young children, mainly boys, would often be taken to games by older relatives, but many would also attend together in small groups. The Merseyside giants, Everton and Liverpool, both had a ‘Boys’ Pen’: an area of the ground set aside specifically for under-12s. When crowd crushes or surges occurred on the terraces (which was often), these young fans would be removed from the affected areas or otherwise ‘looked after’ by other spectators concerned about their safety. The absence of these two groups of supporters meant that there were greater proportions of young men and teenage boys – precisely those supporters most likely to participate in football violence – and while this didn’t on its own lead to racist behaviour, the combination of football-related violence and racist behaviour served to make the atmosphere at football grounds more poisonous.

Elsewhere, the start of the 1976 season saw Cunningham continue to produce stellar performances for Orient, but the side struggled both on and off the pitch. Performances and results were poor and the club was crippled with debt. As the season dragged on, it became clear that due to the club’s huge debts and poor form, it was a case only of when, not if, Cunningham was to be sold. There was speculation about where he might go. Johnny Giles, the player-manager of West Bromwich Albion who had taken the Baggies to the First Division, contacted Orient, a fee was agreed and Cunningham was eventually sold, the first of the legendary Three Degrees to join the West Midlands outfit in March 1977.

A few months later, Cyrille Regis joined him. Regis was born in French Guiana and arrived in England, aged five, without being able to speak any English. A good sportsman, his first love was cricket, at which he represented his county at school level, and although he played football like any other boy of his age, he didn’t excel. At secondary school, he wasn’t good enough to get into his school football team until he was thirteen. He first played on the right wing and then moved to the striker’s position, where he found that he could score goals. His strength was his speed and he blossomed into a prolific striker and was selected to play representative football for the Borough of Brent. Along the way he had played for a team called Oxford & Kilburn with future England cricket captain Mike Gatting and Mike’s brother Steve, who later played for Arsenal and Brighton. However, it was Cyrille’s performances playing Sunday league that got him noticed and he signed for Moseley in the Athenian League in 1976.

The Athenian League was developing a reputation as a decent source of black footballing talent. The previous year, Phil Walker and Trevor Lee had left Epsom & Ewell to begin a successful stint at Millwall. The eighteen-year-old Regis scored twenty-four goals in his debut season, earning him a transfer to semi-pro outfit Hayes Football Club. Combining work on building sites as an apprentice electrician with playing non-league for Hayes, he scored another twenty-five goals in his first season for them. Fifty goals in two seasons alerted a crop of scouts from league clubs. Eventually it was Ronnie Allen, chief scout at West Bromwich Albion, who persuaded his bosses to pay the £5,000 transfer fee Hayes wanted. Legend has it that Allen offered to pay the transfer fee for the young Regis himself. As Cyrille put it:

Story goes that they weren’t sure about me, not that they’d seen me play or whatever, but it came down to money. Five grand and another five grand and Ronnie Allen said, ‘Well, I’ll buy him with my own money and when he makes it, give me my money back.’ But there’s also another story that what persuaded him to buy me was he came down to watch me play at Hayes … The ball came across from a corner and I went up for a header … Myself, the goalkeeper and two defenders, and the ball ended up in the net and so that persuaded him to buy me.

Along with his capacity for scoring goals, one of the key criteria that had persuaded Allen to bring Regis to Albion was his strength, which was to earn him the nickname of ‘Smokin’ Joe’ due to his alleged similarity to former heavyweight boxing champion Joe Frazier. The name epitomised the somewhat crude depiction of black players at the time, which chose to focus almost exclusively on their physical attributes. Undoubtedly, Regis was strong and powerful and he was also quick, but this description belied his other attributes. Regis would not have been able to play in the top flight for so long and represent England at international level had he been simply a battering ram of a striker. His hold-up play was intelligent and cunning. His ability to bring others into play was exceptional. His movement was clever and incisive and his finishing was as good as any of his contemporaries. These more cerebral attributes that apply to Regis as well as other black players were rarely analysed in any great detail by a media constrained by a distinctly nineteenth-century perception of black people – and, by extension, black footballers – as ‘exotic’.

Football, like many sports, is a game where clichés are in abundance, and within English football they are rife. These clichés often act as a convenient shorthand to convey ideas and concepts. However, in the case of black footballers from this era, the clichés served to present information in a way that not only offered a limited version of the truth but also suggested that the style of play that black players brought to the game was purely and exclusively physical and therefore of limited merit. Bobby Robson, in assessing Johnny Miller, said, ‘Miller had potential without ever really fulfilling it … He didn’t seem to have the aggression and commitment that I was looking for … At the time there was this feeling in the country that coloured players lacked heart. I must admit that I asked myself a number of times, could it be right?’

Germans may be efficient and ruthless, which provides a useful explanation for their prowess at penalty shoot-outs, but this doesn’t preclude admiration for their technical ability. Brazilians possess a rhythmic, samba-inspired footballing style and although popular wisdom often fails to appreciate that the technical ability of Brazilian footballers is rooted in their country’s cultural notions of how football should be played, combined with hours of practice to hone that technique, it’s at least admired for its beauty and success. The clichés surrounding black footballers were never juxtaposed with an appreciation of their intelligence and their tactical discipline and awareness. If speed were the only attribute required to play on the wing, that position would be dominated by Olympic sprinters. If strength were the only attribute required to play as a target man, that position would be dominated by powerlifters. Good defensive tactics can often negate speed and strength, and the challenge to overcome this requires a level of strategic thought and planning that often goes unappreciated, even by those who have been involved in the game at the highest level. Knowing how to make the best use of your speed or how to best utilise strength has been a key challenge for generations of footballers, but in spite of achieving this week after week and season after season, the same lazy clichés dominated the perception of black footballers for several decades.

• • •

‘I was like, where’s West Brom? You hear it in the scoresheet, but I didn’t know where West Brom was.’ – Cyrille Regis

The timing of Regis’s shot at the big time couldn’t have been better. He had just completed his exams and was now a fully qualified electrician. Albion offered him a one-year contract. His employers wished him well and offered him his job back if it didn’t work out. Although he had absolutely no idea where West Bromwich was, he was both excited and apprehensive at the prospect of becoming a professional footballer. Staying in club lodgings in Handsworth, an area of Birmingham with a large Caribbean community, the nineteen-year-old Regis began his professional career. Laurie Cunningham was already at the club, but as Cunningham trained with the first team, Regis, on the reserves, didn’t have a great deal to do with him at this stage.

Regis’s career at Albion began well. Chief scout Ronnie Allen had taken over as first-team manager after Johnny Giles had resigned and Regis had played regularly for the reserves, scoring on his debut. He scored twice on his first-team debut, in a League Cup game against Rotherham, and again on his league debut in a victory over Middlesbrough. In his own words: ‘I’d settled well. I was living in Handsworth, where I felt comfortable, even though I was far from home and I’d had a great start to my career. Strikers are judged on scoring goals and it’s so important to get off to a good start.’

He was blossoming in his quest to make the big time, but something else was happening as well. ‘It was great having him around,’ Regis said of his new-found friendship with Laurie Cunningham.

He kind of took me under his wing and we became friends almost immediately. It was good that one of the first-team players took an interest in me and, with him being black and from London, made it more important. I looked up to him and it’s only when I think back now that me being there was as good for him as it was for me.

Regis highlights the two factors that were key to his initial development at West Bromwich Albion. Of course, he was hungry. As a raw nineteen-year-old, he was keen to show what he could do in the top flight of English football. Although it’s a matter of conjecture as to whether Ronnie Allen had paid for Regis’s transfer out of his own pocket, the manager nonetheless had some form of investment in him and was prepared to give him an extended run in the side. His hunger and the belief of his manager were important factors, and these alone may have been enough to guarantee his success at Albion, but equally important were his friendship with Cunningham and his residency in Handsworth. Regis remembers: ‘We’d be seen in and around Handsworth and we soon became popular in the black community. People would come up to us and you started seeing black kids taking a real interest in going to football matches.’

His friendship with Cunningham was an important part of his initial experience and, ultimately, with the arrival of Brendon Batson, was to define his career at Albion. Playing up and down the country, suffering the taunts together, created an important bond in helping the two players to deal with the abuse they received. For Cunningham, this was equally important. Up until then, he had been the only black player at the club. Here was someone who was able and willing to share the load.

Handsworth was also an important part of Regis’s ‘settling-in’ period. Becoming a part of a black community provided him with an opportunity to escape from the pressures of justifying his blackness. In Handsworth, he could just be himself. In turn, he became an instant hero amongst the black community. The ability of black players to deal with racist abuse and use the experience as a source of motivation gave inspiration to black communities not only in Birmingham but throughout the country. The experiences of black players in suffering racist abuse mirrored their own experiences, but differed in an important dimension. The dehumanising effects of both racist abuse and racial discrimination offered very few opportunities to resist their impact. Football provided an opportunity to hit back. Here were players who not only took the abuse but turned the taunting of their abusers on its head in order to perform well on the pitch. For black communities therefore, black players who were scoring goals, making goals, tackling and playing well were resisting and fighting back in the only way they were able.

As Regis put it, ‘Black people of all ages would just want to talk to us or just wish us well. I suppose in some way they wanted us to know that we had their support and we weren’t doing this on our own.’

Regis had quickly established himself as a first-team regular. However, before 1977 had ended, Ronnie Allen had taken up an opportunity to manage the Saudi Arabian national side and Albion were on the hunt for a new manager. Veteran defender John Wile was installed in a caretaker role, but Albion appointed a young and hungry manager who’d done very well with unfashionable Cambridge United. Ron Atkinson was to change Albion’s fortunes and play a pivotal role in changing the way that black players were perceived and the way in which incidents of racism were handled.

• • •

Arsenal had won the historic league and cup double in 1971. Their domestic dominance was further underlined by the fact that their youth team, containing Brendon Batson, had won the FA Youth Cup the same year. Batson was born on the Caribbean island of Grenada and had arrived in the UK at the age of nine. He was spotted as a thirteen-year-old playing representative football for his district and signed as an apprentice at fifteen. First-team opportunities had eluded Batson and he made only ten appearances in three seasons. He moved to Cambridge United in 1974 and joined a team in the fourth tier of English professional football. United had only been a league outfit since 1970 and there was an amateurish quality to the whole club. For Batson, this was a far cry from his beginnings at Arsenal: ‘At Arsenal the apprentices were raised to be gentlemen as part of our development. We were introduced to fine food, told to dress well, taught good manners and taught discipline. When I went to Cambridge, I wondered what have I got into here?’