Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

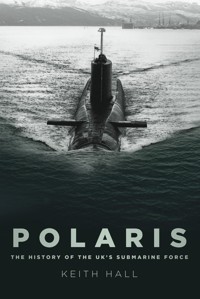

Between 15 June 1968 and 13 May 1996, the Polaris submarines of the 10th Submarine Squadron carried out a total of 229 patrols, travelling over 2 million miles. Wherever you sit on the nuclear debate, it makes an impressive tale; delivered on time and on budget essentially by a small group of naval officers and civil servants, the Polaris programme ensured that Britain had a Continuous at Sea Deterrence for twenty-eight years. Polaris is not just the history of the weapons, submarines and politicians: it is the history of those who were there. Combining through history with personal memories and photographs, Keith Hall has created a long-lasting legacy to a fascinating project and provided an insight into a world that no longer exists.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Children on Rhu Spit, waving goodbye.

All royalties raised from the sale of this book are being donated to the Friends of the Submarine Museum

First published 2018

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Keith Hall, 2018

The right of Keith Hall to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7509-8850-6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed in Great Britain

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword by Bob Seaward OBE

Introduction

1 In the Beginning

2 Britain and the Bomb

3 The Polaris Project

4 And so to Work

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Bibliography

Also by the Author

Friends of the Royal Navy Submarine Museum

FOREWORD

The United Kingdom’s independent strategic nuclear deterrent is a weapon of peace, not war. Throughout the period known as the Cold War, the Polaris weapon system in various forms of upgraded capability was on continuous deployment, ready at all times to retaliate to a pre-emptive nuclear attack on the United Kingdom or members of the NATO alliance. The unimaginable outcome of an attack of this kind, the inevitability of mutually assured destruction (MAD), deterred the use of nuclear release during its in-service life and after with the introduction of the Trident weapon system.

I am honoured to pen the foreword to this most informative and personal salute to the Polaris project, which stands alone as an example of managerial, logistical and leadership competency, both in its planning and execution. A project of this magnitude and complexity has not been equalled since. Not only did the team procure a completely new major weapon system under that very special relationship with the United States but they designed and built the submarines to carry them. To house all this, they constructed the two sizeable bases to support these submarines and their weapons, and provided the especially trained personnel to man them. The submarines came on stream in June 1968 and carried the national deterrent until May 1996, when the responsibility passed to the Trident weapon system. The four Polaris submarines of the 10th Submarine Squadron carried out a total of 229 operational patrols, their unbroken service ensuring that the UK’s nuclear deterrent was available and ready to launch at all times.

My own submarine service spanned the Cold War years from 1969 to 1994, during which time I spent eighteen years in support of the Polaris deterrent both at sea and ashore. First I became an integral part of the strategic weapon system as the navigating officer of HMS Resolution, then gained further experience as an executive officer, before holding a key operational planning role at Polaris headquarters in Northwood. I had successful command of HMS Repulse, launching a batch of y missiles at the US demonstration and shakedown facility at Cape Canaveral, then a second command, of HMS Revenge, before an MoD appointment to the Nuclear Policy Directorate. A committed believer in the independent strategic nuclear deterrent, I would not have missed a day in its service.

The author also spent the majority of his submarine service in support of the Polaris weapon system, part of that unique team providing continuous at sea deterrence. It was during the long periods at sea on patrol that hobbies were indulged. Some members of the ships’ companies chose model making, others took up art projects, some studied for Open University degrees and Keith Hall developed his interest in submarine history, in time publishing a series of books and articles about submarines and their supporting bases. This book is a comprehensive record of the incredible Polaris project from inception to replacement. Keith is a firm believer that the rapid development of the UK Polaris fleet and its timely operational deployment was a truly outstanding political and management achievement only made possible by the determination and leadership of Admiral Sir ‘Rufus’ Mackenzie KCB, DSO, DSC a former flag officer submarines appointed Chief Polaris Executive, responsible to the Controller of the Navy, an equally talented Vice Admiral Sir Michael Le Fanu GCB DSC. They were a formidable couple.

The early chapters of this book chart the history of the United Kingdom’s international relationships, periods of conflict, development of war fighting capability and the complexities of political discord that resulted in the Iron Curtain dividing Europe. From this grew the need to establish a defence mechanism through deterrence. The creation of the independent strategic nuclear deterrent is catalogued in detail, including details of the political and technical exchanges between the UK, USA and France before the decision was made bilaterally to proceed with Polaris. Thereafter, we are shown the ‘Who’s Who’ of the 10th Submarine Squadron when it was reformed in 1967 and the lists of commanding officers of the four Resolution Class submarines. The reader is then treated to a guided tour of a Polaris submarine and an insight into the way our lives were conducted in support of this unique part of the UK’s military capability. For the curious, this is perhaps the most interesting section as it answers the questions so frequently asked: What does it feel like to be underwater? Do you ever suffer from claustrophobia? What happens if you go sick? What is the food like? What would you feel if you had to fire these missiles for real? With all that time spent in the system there will be so many anecdotes to record and tell. Perhaps this will appear in time as an amusing sequel to a very serious but proud story.

Bob Seaward OBE

A Bomber Man

INTRODUCTION

The world immediately after the Second World War was a very different place to the one we know today, even with all its uncertainties and insecurities. Although Russia, America and Britain had been allies during the last four years of the war, it would be fair to say it was a far from harmonious relationship and disagreements that had existed throughout the war continued and even intensified after the defeat of Germany. Age old cultural and political differences between East and West came to the fore, only this time as a result of contradictory interests, misinterpretations and especially the introduction of nuclear weapons. The troubles between the superpowers reached new heights and resulted in a self-perpetuating, spiralling competition to better one another. Looking back, even over this relatively short period of time, it is hard to imagine the feelings of apprehension and foreboding that were felt throughout Europe after the Second World War. Countries were shattered and their people’s hopes of a peace, a new just world, were not realised, or at best, would take some time to materialise. In Britain, a victor of the war, cities lay devastated, rationing was still in force and was to remain so until 1953; the country was all but bankrupt. Was this the country that so many people had died defending? It was no fit place for heroes.

After the war, most of Europe was occupied by the three victorious countries. The Russians created an Eastern Bloc of countries, annexing some as Soviet socialist republics, in others they installed puppet governments, and these satellite states would later form the Warsaw Pact. In other parts of the world, Latin America and Southeast Asia, for example, Russia encouraged Communist revolutionary movements. Needless to say, America and many of its allies opposed this and, in some cases, attempted to obstruct or even topple these puppet regimes. America and various Western European countries began a policy of containment, which became known as the Truman Doctrine, in an attempt at a European Recovery Programme (ERP). This was a plan to aid Western Europe in which America gave $13 billion (approximately $130 billion in today’s money) in economic support to help rebuild Western European economies after the end of the war. Several alliances were forged to combat the Russian threat, most noticeably the formation of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) on 4 April 1947.

In the years after the war the Russians were making threatening radio broadcasts into Finland, while revolts that broke out against the communist governments in East Germany in 1953 and in Poland in 1956 were ruthlessly put down. Also in 1956, Hungary was invaded after trying to break free from Russian control. American nuclear-armed Thor missiles were stationed in Eastern England. All this added to the general atmosphere of distrust, cynicism and concern that prevailed throughout much of the world and was further fuelled by politicians’ responses to events that they did not properly understand. Public fears reached new heights during the Cuban missile crisis in October 1962, a thirteen-day confrontation between America and the Soviet Union when Russian ballistic missiles were deployed in Cuba. I remember reading about an RAF officer who was stationed at a Thor missile battery at this time, when these missiles were at full alert ready to launch. He was stood down for a few hours and took the opportunity to go home and see his family, who lived nearby. When he got there he was surprised to see his young children playing with their Christmas presents on the front lawn. He asked his wife why she had given the children presents early. She told him she was so worried about the current world situation that she was convinced none of them would be alive at Christmas. She certainly wasn’t alone in this view.

Although the two prime contenders never fought one another directly, there were several proxy wars and unimaginably vast amounts of money were spent on espionage, weapon developments, propaganda and competitive technological development, the most obvious of which was the space race. Initially the responsibility for the Cold War was placed on the Russians; Stalin had broken promises he made at Yalta by imposing Russian-dominated regimes on reluctant Eastern European states. Also, his paranoia and ego did little to quell Western fears and this was further increased by his stated aim to spread communism throughout the world. This left America and her allies with little option but to respond.

During the 1960s an alternative view was proposed. It was claimed that America had made efforts to isolate and confront Russia well before the end of the Second World War. The main motivation was the promotion of capitalism and to this end they pursued a policy that guaranteed an open door to foreign markets for American business and agriculture across the world. It was reasoned that a growing domestic economy would lead to a bolstering of American influence and power internationally. It has also been stated that the Russian occupation of Eastern Europe might have had a defensive rationale, enabling the Russians to avoid ‘encirclement’ by America and its allies; it would also provide a buffer zone against invasion. It was argued that Russia was devastated, both physically and financially, at the end of the Second World War; it was highly unlikely she could pose a credible threat to America, particularly as at this time, America was the only country with the atomic bomb. However, in view of Russia’s actions after the war it is particularly difficult to support these arguments. Controlling repressive governments need an enemy, real or imaginary, to justify and defend their oppressive regimes. Conversely, it could be argued that even the more moderate regimes used the Cold War to justify certain policies and weapon programmes.

Until August 1957 Europe could safely ‘sit’ under the ‘American nuclear umbrella’, where the Americans convinced the Russians that any level of attack would result in massive nuclear retaliation. Things got a little more complicated at that time when the Russians successfully launched the world’s first intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) and two months later, on 4 October, launched the first Earth-orbiting satellite, Sputnik. To complicate matters further, a little later they reached nuclear parity. This left the Americans with basically two choices: surrender or face annihilation. In response American policy makers looked to Europe to do more in its own defence and introduced various strategies to achieve this.

America has maintained substantial forces in Britain since the Second World War and this has done little to allay people’s apprehensions. In July 1948, the first American deployment began with the stationing of B-29 bombers. The radar facility at RAF Fylingdales is part of the American Ballistic Missile Early Warning System, the base is operated entirely by British personnel and has only one USAF representative, mainly for administrative purposes. Several other British bases have a significant American presence including RAF Croughton, RAF Alconbury and RAF Fairford. British military forces also deployed American tactical nuclear weapons under a NATO nuclear sharing policy. These included nuclear artillery, nuclear demolition mines and warheads for Corporal and Lance missiles deployed in Germany. The RAF also deployed American nuclear weapons – the Mark 101 nuclear depth bomb on Shackleton maritime patrol aircraft. Later this was replaced by the B-57, which was deployed on RAF Nimrod aircraft. These arrangements stopped in 1992. Britain also allowed America to deploy nuclear weapons from its territory, the first having arrived in 1954. During the 1980s nuclear-armed USAF Ground Launched Cruise Missiles were installed at RAF Greenham Common and RAF Molesworth. Nuclear bombs were also stored at RAF Lakenheath for deployment by based USAF F-15E aircraft. During the Cold War, critics of the special relationship jocularly referred to the United Kingdom as the biggest aircraft carrier in the world. Britain and America also jointly operated a military base on the Indian Ocean island of Diego Garcia and on Ascension Island, a dependency of Saint Helena in the Atlantic Ocean. During this period, the United States Strategic Air Command (SAC) kept 30 per cent of its nuclear armed bombers on alert, their crews ready to take off within fifteen minutes. In the early 1960s, during periods of increased tension, B-52s were kept airborne all the time and this practice continued until 1990.

Throughout this period Britain’s nuclear policy was based on nuclear interdependence with America, although British political leaders often referred to this, and certainly tried to sell it to the public, as independence. Operational control of the Polaris force was assigned to Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) and, like the V bomber force, targeting policy was determined by NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). At times when the missiles would be launched without Britain’s NATO allies, the independent targeting policy would apply. This relied on the ‘Moscow criterion’, basically Britain’s capacity to retaliate against the centralised command structures concentrated in the Moscow area. In 1980, US President Jimmy Carter changed the original American MAD doctrine in by adopting a ‘countervailing’ strategy under which the planned response to a Soviet attack was no longer to bomb Soviet population centres and cities, but first to kill the Soviet leadership, then attack military targets, in the hope of a Soviet surrender before total destruction of the Soviet Union. This policy was further developed by the Reagan administration with the announcement of the Strategic Defense Initiative (nicknamed ‘Star Wars’) that aimed to develop a space-based technology to destroy Russian missiles before they reached America.

Events don’t happen in isolation, they are all interconnected, like interwoven threads. They are twisted by people’s interpretation of these events, which are influenced by their own aims, often their own personal aims, and perhaps with an eye to the future and how they want history to remember them. At the end of the day all we can be sure of is what happened, and this book tells the incredible story of the British Polaris project, which by any measure is a truly epic story and a truly a remarkable achievement. It stands alone as an example of managerial, logistical and leadership competency, both in its planning and execution, that even some sixty years later has not been equalled. Not only did the team procure a completely new major weapon system but it designed and built the submarines to carry them, constructed the two sizeable bases to support these submarines and their weapons and provided the correctly trained personnel to man them. Once the submarines became operational between 15 June 1968 and 15 May 1996, the four Polaris submarines of the 10th Submarine Flotilla carried out a total of 229 operational patrols, ensuring the British Continuous At Sea Deterrent (CASD) was ready at all times.

To try to put the Polaris project in context, Chapters 1 and 2 detail Cold War history and the British nuclear weapon programme, admittedly somewhat briefly but I hope it gives readers an overview of the background to the project. Being a Royal Navy project with more than a smattering of American input, acronyms abound. I have purposely avoided including a glossary and I explain the abbreviations in the text, avoiding the need for the reader to flip backwards and forwards through the book. For a similar reason, I have not included footnotes or references. If readers require further information, they should refer to the texts in the bibliography.

This is a story that I and my family were a part of; admittedly a small part but, as I’m sure it was for many others involved in the Polaris project, it was an enjoyable part and, I felt, a well worthwhile one. I also hope it is a story you will enjoy.

1

IN THE BEGINNING

Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, felt that a general election should be held as soon as possible after the Second World War ended; not to do so, he believed, would be a very serious constitutional failure and the majority of his party agreed with him. However, when the war ended in Europe on 8 May 1945 he reconsidered his decision and proposed to Attlee, the Labour Party Leader, that the election should be delayed until the Japanese had been defeated. Many Labour ministers in the Coalition agreed with his reasoning, although Herbert Morrison, the Home Secretary, did not. This proposal was put to the Labour party conference on 20 May 1945 and was overwhelmingly rejected; they wanted the election to be held sooner, despite Attlee wanting the election delayed until October. He argued that it would be impossible to compile an accurate register of voters any earlier. Atlee’s decision was undoubtedly motivated by the fact that, the sooner the election was held the more the Conservatives would benefit from Churchill’s respected position as the country’s wartime leader. Probably as a result of this, Churchill called for an election much earlier than Labour had wanted. He resigned as leader of the Coalition government on 23 May 1945 and agreed to form what became known as the ‘Caretaker Government’ until the dissolution of Parliament, a few months later, on 15 June 1945.

Regrettably for the Conservatives their election campaign depended, almost entirely, upon Churchill’s personal popularity; in fact, their manifesto was initialled ‘Mr Churchill’s Declaration of Policy to the Electors’. It highlighted five areas that the Conservatives considered essential if the country was to recover from its post-war desolate state. They were: completing the war against Japan, demobilisation, restarting industry, rebuilding exports and a four-year plan regarding food, work and homes. Unfortunately it totally failed to address the people’s concerns and priorities. On the other hand, the Labour Party manifesto detailed a wide-ranging set of proposals for the rebuilding of the devastated post-war Britain. Their plan proposed a programme of nationalisation that included: the Bank of England, fuel and power, inland transport and iron and steel. It also proposed that there should be controls on raw materials and food prices, government intervention to maintain employment, a National Health Service, social security, and controls on where industries should be located. This was much more in keeping with the voters’ priorities. Housing, the last consideration for the Conservatives, was the overwhelming top priority for the voters, along with jobs, social security and nationalisation. Not surprisingly, Labour won a landslide victory – 393 seats to the Conservatives’ 213.

Regrettably, the cost of the war shone the cold light of reality on these optimistic dreams. Although the actual costs were unknown, the war placed a colossal strain on the country’s finances; it was estimated that approximately one quarter of the nation’s wealth, some £7 billion, was spent on the war effort and the national debt had tripled. The leading British economist, John Maynard Keynes, who at the time was the chief economic advisor to the Labour Government, warned that the country was living well beyond its means and he thought that the country would not be able to enjoy its pre-war, world power position. He estimated the overspend to be in the region of some £2 billion a year. He stressed that without the lend-lease agreement with the US it was doubtful that the country could have won the war and once this arrangement ceased the country’s worldwide commitments would in all probability have to be reduced with the related loss of national prestige. To avoid this, Keynes estimated, the country would need a loan of $5 billion dollars and America was the only credible source for this. He thought that if this loan was unobtainable the country’s future could be likened to a second-class power, which he equated to the present state of France. This was an intolerable situation for British politicians, who still imagined the country’s world standing in its pre-war state.

During the war the Americans supplied Britain, Russia, China, France and other allied nations with war materials and food. This aid programme became known as lend-lease, in which a total of $50 billion (approximately $639 billion in today’s money) worth of supplies was shipped to these countries. Once this stopped, Clement Attlee sent Keynes to America to obtain this loan and much to his credit, despite his ill health, he managed to secure $3.75 billion. The Canadians also loaned C$1.25 billion and the country also received £2.4 billion from the European Recovery Programme (the Marshall Plan). Even with these loans, money was still very tight and the Government was forced to adopt other money-saving solutions. Attlee’s government introduced import controls and continued the wartime practice of rationing food. In fact, it got worse and between 1947 and 1948 about half of consumer expenditure on food was rationed. Such staple foods as meat, cheese, eggs, fats and sugar were rationed; bread had been rationed in July 1946, followed by potatoes in November 1947. Rationing was slowly relaxed between late 1948 and 1954, but coal remained rationed until 1958. The Government also implemented defence cuts, which caused Herbert Morrison to express his concern in November 1949 by stating the country could be paying more than it could afford for an inadequate defence organisation. The government also reduced capital investment, affecting roads, railways and industry. As promised, Labour embarked on a massive programme of nationalisation, with approximately 20 per cent of the economy involved. On top of this, the government created the very expensive National Health Service.

Despite the loans and Labour’s best efforts, by 1947 the country’s economy was in crisis. At the TUC conference in 1948, the Labour chancellor Sir Stafford Cripps announced, ‘There is only a certain sized cake. If a lot of people want a larger slice they can only get it by taking it from others.’ He had already introduced a wage freeze in his austerity budget the year before. The government’s problems were further compounded when the winter that year turned out to be one of the worst on record and the wheat harvest failed, adding to the rationing problems and further increasing difficulties with the country’s food supply. In 1949 Britain was forced to devalue the pound, from US$4.03 to US$2.80.

And while all this was going on, unnoticed by most, the next war had already started, or perhaps more correctly, entered a new phase: the Cold War. It was a name given to the post-war tensions between America and its allies and the Russian-led countries. It was a peculiar war. A proxy war. The main participants never directly fought one another, but in one way or the other it was a war that affected the lives of most of the people in the world. It was a war without a clear-cut start and, despite the celebrations during 1991, it’s a war that’s probably still in progress.

Despite their common origin – both America and Russia were born from revolution – they developed very different ideologies and very different attitudes in their dealings with the rest of the world. In America the state had little influence over the day-to-day life of its citizens; the Constitution limited the state’s power. In contrast, primarily due to the influence of Eastern Orthodoxy and rule of the Tsar, Russia was a bureaucratic, land-based power that saw its security in terms of the land it owned. Additionally, there were major differences in the attitudes regarding empire-building. The Americans, along with many other Western nations, were primarily seafaring nations, whose economies were largely trade-based, whereas Russia tended towards isolationism viewing anything outside its direct control with a degree of suspicion.

It seems unlikely that this conflict between the two superpowers could have even been prevented. During the war there was never any real relationship, it was more a union based on need and convenience and the seeds that would grow into the Cold War were probably sown well before the Second World War.

Britain, or the Kingdom of England as it was known then, first established relationships with Russia in 1553 when the English navigator Richard Chancellor sailed to Arkhangelsk. He returned to England but revisited Russia in 1595. The Muscovy Company, which had the monopoly of trade between the two countries until 1698, was formed this year. Relationships were further improved when Peter I visited England in 1697. During the 1720s Peter invited English engineers to St Petersburg, and this eventually led to the formation of a small but nevertheless important ‘expat’ community.

During the eighteenth century the two countries were allies as often as they were on opposing sides in the various European wars. During the War of Austrian Succession they were allies, but eight years later, during the Seven Years War, they were on opposite sides, although they never actually fought one another. The outbreak of the French Revolution caused the two countries to unite in a political alliance against French republicanism. Their invasion of the Netherlands in 1799, which ended in failure, concluded this agreement. The two countries fought in the 1807 Anglo–Russia War, but joined forces against Napoleon in the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15). Both countries became involved with the Ottoman Empire and intervened in the Greek War of Independence (1821–29). Despite the London Peace Treaty, problems with the Ottomans were never fully settled and this eventually led to the Crimean War (1853–56), which saw the British, French and Ottomans join forces against the Russians.

Britain’s objective was to stop Russian expansion into Ottoman Turkey; they were particularly worried about the Russians gaining a Mediterranean port that would allow them to, possibly, control the recently opened Suez Canal. This was to be a recurring theme in the following years. Britain was also concerned about the closeness of the Tsar’s territorially expanding empire in Central Asia to India. This caused a number of conflicts in Afghanistan, which became known as ‘The Great Game’, further increasing the tension between the two countries. For example, in 1885 the Russians invaded Afghan territory, this became known as the Panjdeh Incident. Conversely, the two countries saw fit to join forces in the Boxer Rebellion (1899–1901). In October 1905 Russian ships mistakenly fired on several British fishing boats in the North Sea. Preparations were made for war and a flotilla of submarines was dispatched to engage the enemy. They were subsequently recalled before any ‘shots’, or indeed torpedoes, were fired. Britain was not the only country to find itself in conflict with Russia during the nineteenth century; there were several conflicts between Russia and America all centred on the opening of East Asia to American trade, markets and influence.

In 1907 the Anglo–Russian Entente and the Anglo–Russian Convention made both countries part of the Triple Entente, which led them to form an alliance against Germany and its allies in the First World War.

Many countries including Britain, France, Japan, Canada and America supported the White Russians against the Bolsheviks during the 1918–20 Russian Civil War. The revolution involved two separate coups; in February and October 1917, but it took a further three years for Lenin to finally come to power. America landed troops in Siberia in 1918 to protect its interests; they also landed forces at Vladivostok and Arkhangelsk. This undoubtedly coloured Russian attitudes in their dealings with the Western world over the coming years and hardened their suspicions of it. After this period tensions between Russia and the West turned more ideological in nature.

In the First World War, America, Britain and Russia were allies from April 1917 until the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in November 1917. In 1918, Lenin negotiated a separate peace deal with the Central Powers (the German, Austro–Hungarian and Ottoman Empires and the Kingdom of Bulgaria) at Brest-Litovsk. This further compounded American mistrust of the Russians, it also left the Western Allies to fight the Central Powers alone while allowing the Germans to deploy more troops to the Western Front.