19,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: John Wiley & Sons

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

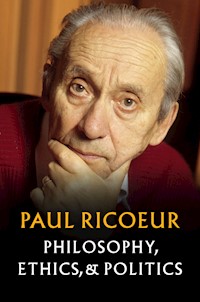

The philosophy of Paul Ricoeur is rarely viewed through the lens of political philosophy, and yet questions of power, and of how to live together in the polis, were a constant preoccupation of his writings. This volume brings together a selection of his texts spanning six decades, from 1958 to 2003, which together present Ricoeur’s political project in its coherence and diversity.

In Ricoeur’s view, the political is the realm of a tension between “rationality” (the attempt to provide a coherent explanation of the world) and “irrationality,” which manifests itself in force and repression. This “political paradox” lies at the heart of politics, for the claim to explain the world generates its own form of violence: the more one desires the good, the more one is inclined to impose it. Ricoeur warns citizens, the guardians of democracy, against any totalizing system of thought and any dogmatic understanding of history. Power should be divided and controlled, and Ricoeur defends a form of political liberalism in which states are conscious of the limits of their power and respectful of the freedom of their citizens.

Ranging from questions of power and repression to those of ethics, identity, and responsibility, these little-known political texts by one of the leading philosophers of the twentieth century will be of interest to students and scholars of philosophy, politics, and theology and to anyone concerned with the great political questions of our time.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 484

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Page

Editor’s Introduction

Notes

Note on the French Edition

I Theological-Political Prologue

1. The Adventures of the State and the Task of Christians

The Twofold Biblical “Reading” of the State

The Twofold History of Power

Our Twofold Political Task

Notes

2. From Marxism to Contemporary Communism

Marxism’s Scope

The Petrification of Marxism

Notes

3. Socialism Today

The Economic Level: Planning

The Social and Political Level: Democratic Governance

The Cultural Level: Socialist Humanism

Notes

II The Paradoxes of the Political

4. Hegel Today

The

Phenomenology of Spirit

, or How to Enter into Hegel’s System

Three theses

Three questions

The

Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences

or Fifteen Years Later

Logic

The philosophy of nature

The philosophy of spirit

Questions

Fascinations

Resistances

Notes

5. Morality, Ethics, and Politics

[The Capable Human Being]

[From the Capable Subject to the Historical Subject]

[Politics, the Milieu Where the Ethical Aim is Fulfilled]

[The Political Paradox]

[Responsibility and Fragility]

Notes

6. Responsibility and Fragility

Rival Cities

Paradoxes of the Political

International Society

Notes

7. The Paradoxes of Authority

[Reciprocity and Dissymmetry]

[The Foundation Before the Foundation]

[Authority and Mutual Indebtedness]

8. Happiness, Off Site

Happiness and What is One’s Own

Happiness and Close Relations: Friendship

Happiness and the Distant: Justice

Notes

III Politics, Economy, and Societies

9. Is Crisis a Phenomenon Specific to Modernity?

Some “Regional” Concepts of Crisis

Criteria for a “Generalized” Concept of Crisis

Criteria for a “Modern” Concept of Crisis?

Notes

10. Money: From One Suspicion to the Next

The Moral Level

The Economic Level

The Political Level

Notes

11. The Erosion of Tolerance and the Resistance of the Intolerable

12. The Condition of the Foreigner

Basic Distinction: “Foreigner” versus “Member”

The Foreigner “Chez Nous”

The foreigner as visitor

The foreigner as immigrant

The foreigner as refugee

Notes

13. Fragile Identity: Respect for the Other and Cultural Identity

The Question of Memory

What is the Cause of the Fragility of Identity?

The Other Experienced as a Threat

The Heritage of Founding Violence

Notes

IV Europe

14. What New

Ethos

for Europe?

The Model of Translation

The Model of the Exchange of Memories

The Model of Forgiveness

Notes

15. The Dialogue of Cultures, the Confrontation of Heritages

Notes

16. The Crisis of Historical Consciousness and Europe

[Exhausting the Project of the Enlightenment?]

[From Dissolution to Reconstruction]

Notes

V Epilogue

17. The Struggle for Recognition and the Economy of the Gift

[Recognition]

[The Gift]

Notes

Origin of the Texts

Index

End User License Agreement

Guide

Cover

Table of Contents

Begin Reading

Pages

iii

iv

vii

viii

ix

x

xi

xii

xiii

xiv

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

Politics, Economy, and Society

Writings and Lectures, Volume 4

Paul Ricoeur

Edited and with an Introduction by Pierre-Olivier Monteil

Translated by Kathleen Blamey

polity

Copyright Page

Originally published in French as Politique, économie et société. Écrits et conférences, 4 © Editions du Seuil, 2019

This English translation © Polity Press, 2021

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

101 Station Landing

Suite 300

Medford, MA 02155, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4386-1 – hardback

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-4387-8 – paperback

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NL

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Editor’s Introduction

Paul Ricoeur’s work is rarely viewed through the lens of political philosophy. And yet the question of power and the desire-to-live-together in the polis is his constant preoccupation and the substance of numerous writings.1 However, none of these themes are presented as part of an overall system in which they are a part. Lectures 1. Autour du politique is composed of studies coming from a wide range of periods and treating apparently unrelated topics.2Ideology and Utopia deals with the political from the standpoint of the social imagination, but the anthropological and epistemological reflections on this topic do not extend to the institutional forms of the political.3 This last aspect is indirectly approached in two other collections, notably through a reflection on the law.4 Finally, the most fully developed text on the political as such is to be found in the series of three studies on ethics, morality, and practical wisdom in Oneself as Another.5

Generally speaking, Ricoeur assigned a limited scope to each of his writings; he himself characterizes his thinking as a style that privileges fragmentation. This is singularly the case in political matters, where he seems to have been unconcerned about confining to oblivion so many studies never to be republished. The selection of the texts collected here has been guided by the concern to repair this oversight by restoring Ricoeur’s political project in its coherence and in the diversity of its centers of interest.6 An initial criterion, that of chronology, has prevailed: retrieving the most salient features of the development of his thought over a period of six decades. This is complemented by a thematic criterion, which has led to retaining the most significant texts and – a more difficult task – setting aside those deemed circumstantial: those with less apparent philosophical intent, as the content was focused on a question specific to a point in time.

The first section brings together texts from the 1950s and 1960s, written in the context of the Christianisme social [Social Christianity] movement during the period, from 1958 to 1970, when Ricoeur was its president. Is there any need to underscore this fact? Since these writings, which contain reflections that remain entirely pertinent today, are related to a political and theological context that is now distant from our own, we have provided in notes, when necessary, some information useful for understanding them. It was indeed within the framework of this Protestant movement that the philosopher first developed his political thought. Far from a Christian apologetic, it was for him a matter of articulating conviction and responsibility, paying particular attention to giving an account of the tradition within which he placed himself, through the mediation of the public debate he solicited. On the basis of this foothold, an evolution ensued, and over its course the philosopher continued, little by little, to strip his formulations of their theological or biblical references, as if increasingly to open them up to discussion in secular terms.

In this respect, the text “The Adventures of the State and the Task of Christians” constitutes the exception that proves the rule. For this 1958 article is the transposition in theological terms of “The Political Paradox,” the seminal text published the preceding year in the journal Esprit, after the Soviet repression of the Budapest uprising in October 1956.7 In these circumstances, the “Christians’ task” is to demonstrate with respect to the State both responsibility, by actively participating in democratic institutions, and critical vigilance. In the first instance, Ricoeur dismisses, back-to-back, anarchism and the apology of submission. In the second, he rejects both millennialist utopia and sterile criticism. The central point is focused on the double-sided reality which is the State, a protective and pedagogical institution, but at the same time the power that is potentially subjugating through lies and illusions.

The parallel with respect to the argument of “The Political Paradox” is clear: the political is the realm of an extreme tension between “rationality” – the explanation it gives of the world – and “irrationality,” which is seen in the use of force, repression, totalitarianism. This internal tension is constitutive of the political, for the claim to provide a total meaning to the world generates violence: the more one desires the good, the more one is inclined to impose it. In this way, Ricoeur warns the citizen, the guardian of democracy, against any totalizing system of explaining the world, any dogmatic understanding of history. As a corollary, power should be divided and controlled. Ricoeur declares himself to be in favor of a political liberalism, that is, a State respectful of limits to its domain and confident in the liberty of its citizens.

In his effort to grasp the political as such, Ricoeur discerns an evil specific to it, the grandeur of the political ambition and its claims. The result of this is a critique of Marxism, published in 1959 in “From Marxism to Contemporary Communism.” If Marxism succumbed to political evil with Stalinism, this is because it, quite wrongly, made political domination the consequence of another evil: economic exploitation. In this text, Ricoeur presents a diagnosis of “the petrification of Marxism.” The following year, however, in “Socialism Today,” he is no less critical in the face of “the gradual downfall of the great dream of the founders of socialism,” degraded to the welfare state. The heirs of Marx and Proudhon are in serious danger of turning away from the fundamental significance of work in human activity, to the benefit of a simple socialization of abundance and, finally, to the promotion of the “common man” (l’homme quelconque). Beyond the question of Ricoeur’s political allegiances – he, the great reader of Marx, is not himself Marxist, but socialist in his leanings – it is his philosophical approach that is especially to be underscored. The terms, “dream,” “decline,” and “petrification” seem to suggest that political evil is accompanied over time by the ideological rigidness of utopia in the domain of the social imagination.

In addition to the preceding two criteria, there is a third, methodological one. It is conveyed in the ample reflection on “Hegel Today,” from 1974, which opens the second section.8 Political evil has its counterpart on the level of thinking, which requires elucidation. What is at issue is the temptation of synthesis, of totalization, the illusion that leads thought astray. Applying this observation to the work of philosophy itself, Ricoeur states his “invincible points of resistance” with respect to Hegelian absolute knowledge. There are intractable aspects of human experience that do not allow themselves to be totalized within a theory. They remind us of the sense of limitation and of the impossibility of attaining a view of the whole. With Kant, we come back to an awareness of the limits of knowledge. From this perspective, the fragmentary style Ricoeur has adopted is highlighted as a philosophical strategy in opposition to the claims of a definitive synthesis. In this sense, there is good reason to see in the texts collected in this volume less an ensemble that forms a system, than exercises of systemization in the critique of system-building.

The reflection on Hegel nevertheless leads to a proposal. In fact, Ricoeur advances the possibility of a function that would be related more to the imagination than to knowledge, here a utopian function, which would be the site of figures portraying the realization of man, in the forward projection of his freedom – rather than in the mode of totalization. The theme of imagination, clearly present in Ricoeur, thus finds an application in the political field. One has only to consider on this point writings that can be found elsewhere.9

The next three texts date from the 1990s. “Morality, Ethics, and Politics” (1993) provides a summary of Ricoeur’s political thinking as it has progressively unfolded since “The Political Paradox.” It is not without importance that this text was published in Pouvoir, a journal intended for constitutional scholars and political figures, as if to solicit a dialogue with interlocutors who were not necessarily philosophers. The major interest of this article is to have set out a multi-storied architecture, after the model of Oneself as Another, superimposing an anthropology, an ethics, and a politics. The political sphere occupies the top level. Among other developments, two new “paradoxes” are added to the first. This construction no longer concerns the cognitive realm alone, but also includes action, sensibility, and temporality. It requires that the citizen be capable of reconciling opposites, combining belonging and distancing, identity and otherness, conviction and responsibility.10 A democratic ethics comes to light, which strives to make both the institution and protest possible, relying on the lived experience of conflict internalized in individuals.11

In “Responsibility and Fragility” (1992), as well as in “Morality, Ethics, and Politics,” Ricoeur conceives of the political by linking it to the ethical.12 This is the corollary of political liberalism. Indeed, once the State abstains from intervening, not everything is political. There are apolitical, or pre-political, margins where civil society flourishes. However, the freedom of action animating social mores and ethical life produces a certain sense of the desire-to-live-together, which in a democracy serves to impress its orientation on the political. In return, democracy is entrusted to the protection of the citizenry, auditors of its fragility. This is highlighted in the 1992 article. To do this, Ricoeur identifies the points of fragility belonging, precisely, to the three figures of the “Political Paradox,” providing to citizens the corresponding themes of vigilance and participation.

Ethics and politics are in a relation of mutual critique. Political institutions are necessary to limit the violence of social mores and actions; but, conversely, they have legitimacy only in the service of democratic ethics. The question of legitimacy, notably, refers back to the question of determining what constitutes authority. In “The Paradoxes of Authority” (1997), an unpublished lecture,13 Ricoeur reflects on the vertical axis of domination. He defines authority as a combination of asymmetry and concealed reciprocity, once authority is viewed to exist only as recognized. In this way, he shows that obedience can be exercised in the name of autonomy – and not against it – if it intervenes in response to a proposal that calls upon one’s autonomy. In this case, domination does not found power, but the other way around. The relation of domination only covers over and occults the roots of a desire-to-live-together, constitutive of the power stemming from acting-in-common (in Hannah Arendt’s sense).14 This brings to light a positive foundation of the social bond, which does not stem from fear. These are the stakes of grandeur: either the citizen obeys power because, in its calling upon him, he grows in stature; or, ceding to the inebriation of grandeur, domination diminishes him, drawing his criticism and his just revolt.

The third and fourth sections extend the perspective to themes related to the economy, society, and to Europe. One should speak of society in the plural here to mark the pluralist dimension affecting these reflections on tolerance, the situation of the foreigner, identity, and, of course, the issues at stake in the difficult elaboration of a European ethos. Broadening the horizon in this way is all the more necessary as, up until the 1980s, the political is often envisaged by Ricoeur in its function of mediation between the economic and the cultural, in reference to the Kantian trilogy of the passions of possession, power, and value.15 But this manner of problematizing no longer appears as systematically after this period, as if the neo-liberal turn prevented drawing any clear line between these three spheres, as they were being overtaken by the logic of the market. In this new context, Ricoeur approaches the economic sphere with a series of probes, as it were, in the studies on money and crisis.

One can then wonder what remains of the critique addressed in the 1960s to the ambition of a “bourgeois” society centered on well-being alone and of a socialism in danger of becoming the promoter of the common man. More circumspect, the argument does not, however, seem to be absent, even as it adopts new forms. This is the case in “The Struggle for Recognition and the Economy of the Gift,” a lecture given by Ricoeur while he was preparing The Course of Recognition, the last work published during his lifetime.16Fearing that an infinite demand for recognition would produce only an insatiable expectation, he introduces a remedy in the struggle for recognition: the gift. This represents the utopian incentive that can keep social exchanges from lapsing into violence. Instead of the unlimited thirst for money, Ricoeur proposes a respite from the race for production and for enrichment. This is doubtless the mark of a continuity – beyond the evolutions of historical context and the shifts in his own thinking17 – a constant preoccupation that runs through his entire meditation on the political: the aspiration for freedom.

Notes

1

See

History and Truth

, tr. C. A. Kelby (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1965);

Time and Narrative

, 3 vols, tr. K. McLaughlin (Blamey) and D. Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984–88);

From Text to Action: Essays in Hermeneutics

, tr. K. Blamey and J. Thompson (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1991);

Memory, History, Forgetting

, tr. K. Blamey and D. Pellauer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004).

2

Paul Ricoeur,

Lectures 1. Autour du politique

(Paris: Le Seuil, 1991).

3

Paul Ricoeur,

Lectures on Ideology and Utopia

, ed. G. H. Taylor (New York: Columbia University Press, 1986).

4

Paul Ricoeur,

Le Juste 1

(Paris: Éditions Esprit, 1995) and

Le Juste 2

(Paris: Éditions Esprit, 2001).

5

Paul Ricoeur,

Oneself as Another

, tr. K. Blamey (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1992).

6

An earlier collection of Paul Ricoeur’s interviews and dialogues,

Philosophy, Ethics, and Politics

, tr. K. Blamey, ed. Catherine Goldenstein with a Preface by Michaël Foessel (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020), concerned ethical and political questions. The present volume offers a selection of articles and lectures collected to shed light on the progress of Ricoeur’s political thought.

7

This article is reprinted in Ricoeur,

History and Truth

, pp. 247–70.

8

This text anticipates “Should We Renounce Hegel?,” a chapter in

Time and Narrative 3

, published eleven years later (pp. 193–206).

9

“Ideology and Utopia,” in

From Text to Action

, pp. 300–16; and

Lectures on Ideology and Utopia

.

10

This task assigns the work of interpretation to citizens. In this way, Ricoeur employs in the domain of the political the “graft of hermeneutics onto phenomenology,” which he had introduced into his philosophical method as early as the 1960s.

11

The figure of the “political paradox” does not refer to a stance of indecision, but to a sense of compromise. Ricoeur himself warns against “what can be paralyzing in a position that oscillates between two poles” in

Philosophy, Ethics, and Politics

, p. 14.

12

On this important axis of Ricoeur’s political project, see the article “Freedom” (1971), reprinted in

Philosophical Anthropology

, tr. D. Pellauer (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2016), pp. 124–48.

13

Unavailable to the general public, considering that this text was published in le

Bulletin de liaison des professeurs de philosophie de l’académie de Versailles

, and had limited circulation. It is, moreover, to be paired with an article on the same topic bearing almost the identical title published in 1996, “Le paradoxe de l’autorité,” in

Le Juste 2

.

14

See also, Ricoeur,

Philosophy, Ethics, and Politics

, p. 27.

15

See Paul Ricoeur, “Ethics and Politics” (1983), reprinted in

From Text to Action

, pp. 317–28.

16

Paul Ricoeur,

The Course of Recognition

, tr. D. Pellauer (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005).

17

A question under debate is whether the encounter with the work of John Rawls marks a social-democratic turn in Ricoeur.

Note on the French Edition

The “Writings and Lectures” in this volume were assembled with scrupulous respect for the original texts, after approval by the Ricoeur Foundation. Modifications made to the body of these texts concern punctuation, typographical errors, and the most obvious inaccuracies that may have appeared in previously published versions. However, the text properly speaking has been retained in its entirety, without changes. Latin or foreign language expressions have been systematically placed in italics. Modifications and complements have been added to quotations and to references, when these were imprecise, incomplete, or absent; I did not, however, find it necessary to underscore all of these. Only the most important have been noted. Missing bibliographical references have been added when the work in question gives rise to a discussion and is not merely cited, with no further commentary. Missing words were added, as were section headings intended to facilitate reading when the original text did not include them. All of these are indicated in square brackets.

I want to thank Marc Boss, director of the Ricoeur Foundation, Daniel Frey, president of the advisory council, Jean-Louis Schlegel, secretary of the editorial board, and Johan Michel for their valuable assistance at every step of this task. I also thank Olivier Villemot for rendering the texts in digital form.

P.-O. M.

ITheological-Political Prologue

1The Adventures of the State and the Task of Christians

The Twofold Biblical “Reading” of the State

It is of critical importance for a Christian interpretation of the State that the New Testament writers handed down to us not one but two readings of political reality: one, that of Saint Paul, leads to a difficult justification, the other, that of Saint John, to a tenacious distrust. For one, the State is the figure of the “magistrate,” for the other, it is the figure of the “Beast.”

We must begin by allowing these two figures to take shape within us, keeping both of them as possibilities, contemporaneous with one another, in every State we encounter.

Saint Paul, addressing Christians in the capital of the Empire – who were little inclined to recognize the authority of a pagan power, foreign to the Good News and, moreover, compromised in the trial that ended in the slow death of the Lord – calls upon his correspondents to obey not out of fear but as a matter of conscience: the State, wielding the sword, which punishes, is “instituted” by God for the “good” of the citizens. And yet this State has a very strange place in the economy of salvation, very strange and very precarious: the apostle has just celebrated the greatness of love – love, which creates reciprocal ties (“Love one another in brotherly love”) – love which forgives and repays good for evil. Now, the magistrate does not do that: the relation between the magistrate and the citizens is not reciprocal. He does not forgive, he repays evil for evil.

His province is not love but justice; the “good” he serves is, therefore, not the “salvation” of humankind, but the maintenance of “institutions.” One could say that through him a violent pedagogy is continued, a coercive education of human beings as members of historical communities, organized and governed by the State.

Saint Paul does not say (and perhaps does not know) how this pedagogy, penal in nature, is related to Christ’s charity: he only knows that this instituted order (taxis in Greek) realizes God’s intention concerning human history.

And at the same time he attests to the divine meaning of the institution of the State, Saint Paul reserves the possibility of an opposing reading. For, at the same time as this State is an “institution,” it is also “power.” Following the somewhat mythical conceptions of the era, Saint Paul pictures a more or less personalized demon hiding behind each political entity; now, these powers have already been vanquished on the Cross – at the same time as the Law, Sin, Death, and other powers – but are not yet annihilated. This ambiguous status (“already” but “not yet”), on which Oscar Cullmann1 has decisively commented, does much to illuminate the theological significance of the State: intended by God as an institution, half-way between condemnation and destruction as power, altogether out of kilter with the economy of salvation, and in reprieve until the end of the world.

It is therefore not surprising that in another historical context, where the evil of persecution overwhelms the good of order and the law, it is the figure of the “Beast” which serves to denote the evil power. Chapter XIII of the Apocalypse depicts, moreover, a Beast, wounded, doubtless mortally, but whose wound is healed for a time; the power of the Beast is not so much the power of irresistible force as of seduction. The Beast produces marvels and demands the adoration of the people; it subjugates through lies and illusions (a description, as we see, close to that of the “tyrant” in Plato, who reigns only thanks to the “sophist,” who first twists language and corrupts belief).

This twofold theological grid is full of meaning for us: hereafter we know that it is not possible to situate ourselves in an anarchism motivated by religion, under the pretext that the State does not declare its belief in Jesus Christ, but nor can we take refuge in an apology for the State in the name of “submitting ourselves to the authorities.” The State is this two-sided reality, at once instituted and fallen.

The Twofold History of Power

We therefore have to orient ourselves in the political sphere by means of this twofold guidance. The modern State advances both along the line of the “institution” (what Saint Paul terms taxis), and along the line of “power,” seduction, and threat.

On the one hand, we can indeed say that there is progress on the part of the State in history; it is even admirable that after so many tears and so much blood, the juridical and cultural accomplishments of humanity have been able to be saved, renewed, and carried further, in short, that humanity continues beyond the fall of empires, as a single being who never ceases to learn and to remember. This perpetuation of humanity, protected by the “institution,” is a kind of verification by history of Saint Paul’s risky affirmation that all authorities are instituted by God.

I will offer four signs of this institutional growth of the State in history.

1. The State is a reality that tends to evolve from an autocratic stage to a constitutional stage. All States are born out of the violence of amassers of territory, wagers of war, inveiglers of dowries and inheritances, subjugators of peoples, unjust conquerors. But we see force moving toward form, becoming enduring by becoming legitimate, associating ever more groups and individuals with the exercise of power, promoting discussion, submitting to the control of the subjects. Constitutionality is the juridical expression of the movement by which the will of the State is stabilized in a law that defines power, divides it, and limits it. To be sure, States succumb to violence through war and dictatorship, but the juridical experience is preserved; another State, somewhere else, welcomes it, and continues it. However slow it may be, however halting, the movement of de-Stalinization, the liberalization of Soviet power, will not escape this law’s tendency, in which, for my part, I see a verification of Saint Paul’s wager on the State.

2. A second sign of this institutional growth of the State is the rationalization of the State by means of its administrative body. There is not sufficient reflection on this important fact, which is just as characteristic of the modern State as its legal system. A State worthy of this name is today a power capable of organizing a body of civil servants, who not only carry out its decisions but develop them without having political responsibility for them. The existence of government service as a politically neutral body has radically transformed the nature of the political. In it, a part of the function of the magistrate is realized, that is, the part of power without political responsibility. This development of a public administration (on the basis of which we judge in part the capacities of young States that have recently emerged in Asia and in Africa) is based in the prolongation of technical rationality, more precisely, in the industrial organization of labor. In this way, power, which is fundamentally irrational as a demonic force, is rationalized by the legal system expressed in the constitution and by the technical prowess expressed in administration.

3. A third sign of institutional progress lies in the organization of public discussion in modern societies. However perverted and subjugated it may be, public opinion is a new sort of reality, which has developed on the basis of a certain number of “political vocations” studied by Max Weber in the past. Militants, office holders, members of parties and unions, journalists, opinion and human relations experts, publicists, and journal editors are the administrators of a new reality, which is an institution in its own right and the organized form of public discussion. Perhaps we should reserve the word “democracy” to designate the degree of participation by citizens in power by means of organized discussion (rather than calling “democracy” the constitutional stage that follows the autocratic stage).

4. Finally, the appearance of large-scale planning represents the most recent form of the institution of the State. The reduction of chance to the benefit of forecasts and long-term projects presents in the economic and social sectors of the life of the community the same kind of rationality which had long since triumphed in other sectors. When the State assumed the monopoly of vengeance and constituted itself as the sole penal force of the community, it rationalized punishment: a table of penalties henceforth corresponds to a nomenclature of infractions. In the same way, the State has defined in a civil Code the different “roles,” their rights and their duties – the role of father, husband, heir, buyer, contracting party, and so on. This codification has rationalized and, in a sense, already set out the plan of social relations. The grand economic plans of the modern State are in line with this double rationalization of the “criminal” and the “civil” and belong to the same institutional spirit.

***

I think we have to state all of this, if we are to give the slightest meaning to what is taking place before our eyes and to avoid an unlimited irrationalism, without bounds and without criteria.

But at the same time we state all this, we have also to say something else, which manifests the endless ambiguity of political reality. All growth in the institution is also a growth in power and in the threat of tyranny. The same phenomena that we have traced under the sign of rationality can also be viewed under the sign of the demonic.

Thus, simultaneously in Germany and in Russia, we have seen constitutions serving as alibis for tyranny. The modern tyrant does not abolish the Constitution, but finds in it the apparent forms and sometimes the legal means for his tyranny, playing with the delegation of powers, the plurality of offices, exceptional forms of legislation, and special powers. The central administration, branching into every aspect of the social body, in no way prevents political power from being completely insane at the top, as we saw during the dictatorship of Stalin. Quite the opposite, to the tyrant’s madness it offered the technical means of an organized and long-lasting oppression. Opinion technologies, moreover, deliver the public over to ideologies at once passionate in their themes and rational in their schematization; the parties become “machines,” where technological prowess in organization is equaled only by the spirit of abstraction driving their slogans, programs, and propaganda.

Finally, the great socialist plans provide the central power with the means of pressuring individuals in a way that no bourgeois State has managed to assemble. The monopoly of ownership of the means of production, the monopoly of employment, the monopoly of provisions, the monopoly of financial resources, and hence of the means of expression, scientific research, culture, art, thought – all these monopolies concentrated in the same hands make the modern State a considerable and formidable power. There is no point in thinking that the government of persons is in the process of being transformed into the administration of things, because all progress in the administration of things (and supposing that planning is a progress) is also progress in the governance of persons. The apportionment of the great financial costs of the Plan (investments and consumption, well-being and culture, etc.) represents a series of global decisions concerning the life of individuals and the meaning of their life: a plan is an ethics in action, and by this means, a manner of governing men and women.

All these threats are tendencies, as are the resources of reason, order, and justice that the State develops as the history of power unfolds. What makes the State a great enigma is that both tendencies are contemporaneous and together form the reality of power. The State is, in our midst, the unresolved contradiction of rationality and power.

Our Twofold Political Task

Before drawing some consequences for action on the basis of this double reading of political reality, is there a need to recall two essential rules?

First rule: it is not legitimate (nor even possible) to deduce a politics from a theology. For any political commitment is at the point of intersection of a religious or ethical conviction, of information of an essentially profane nature, of a situation that defines a limited number of available possibilities and means, and of a more or less risky option. It is not possible to eliminate from political action the tension arising out of the confrontation of these various factors. In particular, conviction which is not tempered by a reflection on the possible would lead to a demand for the impossible by demanding perfection: for if I am not perfect in everything, I am perfect in nothing. On the other hand, a logic of means, not tempered by a meditation on ends, would easily lead to cynicism. Purism and cynicism are the two extremes between which political action moves, wavering in its calculated culpability back and forth between the morality of all or nothing and the technique of realization.

Second rule: political engagement makes no sense for the Church but only for believers. This seems clear in principle, but it is not yet the case in fact: Churches are themselves cultural realities that weigh in the balance of power, and there still remains a more or less unacknowledged, residual, shameful politics of the Church. This is why the secularism of the State has not yet been realized: we are witnessing the death-throes of political and clerical Christianity, and this interminable agony is demoralizing for believers and unbelievers.

It is therefore in terms of the political responsibility of the Christian individual that we must now draw the conclusions of the preceding contradictory analysis.

If this analysis is correct, we have to say that we must at one and the same time improve the political institution in the sense of greater rationality and exercise vigilance against the abuse of power inherent in State power.

***

What sort of institutional improvements are we particularly responsible for today?

1. It seems to me that, first of all, we have to continue constitutional evolution in a reasonable direction, one that takes into account the appearance of new nations in the geographical area controlled by the French State. The number one problem of French politics is transforming the centralized State, inherited from the monarchy and from the Jacobin Republic, into a federal State, capable of bringing together on an egalitarian basis the nations that have emerged within its borders; this invention of new structures would genuinely promote rationality, for it would consist in adapting constitutional reality to the historical, cultural, and human reality of the modern world. The alternative will be decisive: either we do this, and new ties will be made with peoples overseas, or else we do not do this, and these peoples will carve out their own destiny apart from us, even against us.

2. Next, we have to reinvigorate the life of political parties. We cannot say that the experience of multiple political parties is doomed, and that this pluralism simply reflects class divisions: we need a political instrument that will allow citizens to enter into discussion in order to shape and to formulate opinion. The existence of several parties would still be essential, even in a classless society, because it translates the fact that politics is not science, but opinion; there is only one science – and even this is not entirely true – but there are several opinions on questions concerning the direction of public policy. Thus, it is in the interest of democracy that the parties survive the death threats resulting from the weight of bureaucracy, the ossification of party machinery, the false reality of ideologies unrelated to the real problems of the day, and the absurd proliferation and pretentious dogmatism of French political parties. Doubtless, two parties would be sufficient, on condition that they integrate many contradictions, resolved in concrete forms of governance, and that internally they encourage ongoing and open discussion. This is the essential condition for reinvigorating public opinion.

3. We then have to invent new ways for citizens to participate in power other than the election system and parliamentary representation. Here we can learn from the efforts in Yugoslavia, Poland, and other examples of producing new forms of representation for groups of workers and consumers. If a labor-based economy is in view which makes work the dominant economic category, only a political system in which workers would be represented as workers could make this labor-economy a civilization of workers. The task of inventing new forms of representation is perhaps to be combined with the reinvigoration of political parties; it is not simply a matter of defending democracy but of expanding it.

4. Finally, we have to, as people say, reinforce the authority of the State, but in a different way than is often stated. This would not be the primary task if reinforcing the authority of the State is taken to mean increasing the indirect power of several pressure groups over a weak State which, moreover, has not changed its centralized structure and relies on artificial parties, lacking substance, and without internal democracy. And yet this is what is commonly called reinforcing the authority of the State. Now, if this expression has a meaning, it signifies that civil power has authority over military power, over the police and the administration, that the decision-making power belongs to the executive and not to technocrats, that the executive is answerable only to popular representation and not to pressure groups, be they beet farmers or oil magnates.

This action is reasonable action and presumes that the State can be reasonable, that it is reasonable to the extent that it is the State, and that it can become ever more so.

***

However, this reasonable task in view of a reasonable State does not exclude – but, quite the opposite, includes – a vigilance that never lets down its guard, directed against the ever-increasing threat of an unreasonable and violent State.

This vigilance takes several forms.

1. It is first of all a critical vigilance on the plane of reflection. Political philosophy from Plato and Aristotle to Marx has never ceased returning to the theme of political perversions or alienations. But this vigilance wavers when political evil is believed to come from somewhere other than the political sphere, from the conflicts of classes or groups, and that having a good economy is sufficient for having a good political system. Constant reflection on the evils proper to the political, on the passions of power, is the soul of all political vigilance directed against the “abuse of power.”

2. But this vigilance must also take the form of an appeal and an awakening. It is sometimes necessary to appeal to the State on the basis of its founding values. Every State rests on an implicit or tacit consent, on a “pact” that seals a set of common beliefs, common ends, a common good (this is the “good” Saint Paul was speaking of when he said that the magistrate exercises constraint “for your good”). The State can and must be judged on the basis of the values that justify it. Thus, citizens can never be exempt by the State from serving these ideals, and have the duty to condemn actions incompatible with these ideals (exactions, we have to call them); protests against torture flow from this source. At the limit of protest, there is the possibility of illegal actions which have the value of testimony with respect to the “good” upon which the State itself is founded. These acts, in appearance harmful, are in reality very positive; they reaffirm and firm up the ethical foundation of the nation and of the State.

3. Finally, this vigilance has to take a properly political form and link together with the institutional reform we were speaking of earlier. Indeed, we have at one and the same time to reinforce the State and to limit its power: this is the most extreme practical consequence of our entire analysis. This means the following: in the period when we have to extend the competencies of the State in the economic and social arena and to move forward along the path of the socialist State, we have to take up once again the task of liberal politics, which has always consisted in two things: dividing power among various powers, and controlling the power of the executive by means of popular representation.

Dividing power means, in particular, ensuring the independence of judges which the political tends to subjugate. This is what Stalinism ran up against, because the tyrant could not have purged and liquidated his political enemies without the complicity and subservience of the power of the judiciary. But the division of power perhaps implies the invention of new powers which the liberal tradition has not known; I am thinking in particular of the necessity of guaranteeing, and even of establishing the independence of, cultural power, which in fact covers a vast domain, from the university (which has not yet found its appropriate place, between independence with respect to the executive and the anarchical freedom of competition) to the press (which currently has a choice solely between State support or capitalist support), passing by way of scientific research, publishing, and the fine arts. The socialist State, more than any other, requires this sort of separation of powers, by reason of the very economic concentration of power it exercises; more than any other, it needs the independence of judges, of the university, and of the press. If citizens have access to no sources of information other than those of the State, socialist power immediately veers toward tyranny; the same is true if scientific research and literary and artistic creation are not free.

However, power cannot be divided unless executive power is controlled. And here I want to recall how misleading is the dream of the withering away of the State, originating in anarchism and integrated into communism. To be sure, the repressive apparatus of the bourgeois State, its military and police forces, can wither away, but not the State as the power of organization and decision-making, as a monopoly of unconditional constraint. In any case, the State has to be reinforced before eventually withering away. And the problem is keeping it from subjugating people during the no doubt lengthy period in which it will still have to be reinforced. Now, the control of the State is the control by the citizens, by the workers, by the base. It is the movement of sovereignty from the bottom up, in opposition to the government’s movement from the top down, and this bottom-up movement has to be willed, managed, defended, and extended in opposition to the tendency of power to eliminate the forces out of which this bottom-up movement has come. This is the entire meaning of the liberal combat.

***

I have said that there is not a Christian politics, but a politics of the Christian as a citizen. It must be said that there is a Christian style in politics.

This style consists in finding the just place of the political in life: elevated but not supreme. An elevated place, because the political is the primary education of the human species, through order and justice, but not the supreme place, because this violent pedagogy educates human beings in external freedom, but does not save them, does not free them radically from themselves, does not make them “happy,” in the sense of the Beatitudes.

This style consists as well in the seriousness of the engagement, without the fanaticism of faith. For the Christian knows that she is responsible for an institution that is God’s intention with respect to human history, but she knows that this institution falls prey to a vertigo of power, with a desire of divinization that clings to it, body and soul.

Finally, this style marks a vigilance that wards against sterile critique as well as against millennialist utopia.

A single intention animates this style: making the State possible, in accordance with its proper destination, in this precarious interval between the passions of individuals and the preaching of reciprocal love, which forgives and repays good for evil.

Notes

1

Oscar Cullmann,

Christ and Time: The Primitive Christian Conception of Time and History

, tr. F. Filson (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 3rd edition, 2018).

2From Marxism to Contemporary Communism

Up to what point is contemporary communism, guided by the Party and bound up with the political fate of the Soviet Union, the sole and legitimate heir to Marx and, more specifically, to his written work?

The question occupying us here is prior to all discussion broadly concerning Marxism and orthodox communism.

I would like to show that, from Marx to Stalin, there exists a considerable gap, that from one to the other, Marxism has continued to close itself off, conceiving of itself more and more dogmatically and in a more mechanistic sense. Political Machiavellianism has smothered it as free thought; its eschatology has been reduced to a technological aspiration. And yet Marxism is more comprehensive than its Stalinist projection.

We are going to try to understand this movement of Marxism’s progressive crystallization.

Marxism’s Scope

We must go back to the young Marx’s philosophy: it truly constitutes the nebula of Marxism. The roots of this philosophy extend down into the theology of the young Hegel.

It is indeed in the Early Theological Writings that the theme of alienation, in the sense of the loss of human substance in an Other than self, is developed in Hegel. For the young Hegel, initially the Jew was the model of this consciousness, canceling itself by emptying itself in a foreign Absolute. However, throughout his entire life, Hegel will try to show the fruitfulness of this “unhappy consciousness,” at least when it is superseded, surpassed, and integrated into absolute knowledge, in which consciousness and its Other are reconciled. Feuerbach would take up the original theme once more and turn it into a radical atheism: if man prostrates himself before God, his task is to “receive … the rejected nature into his heart again”;1 if God appears when man is annihilated, God must disappear in order for man to reappear.

Marx’s atheism is constituted as an extension of this atheism: Marx was atheist and humanist before he was communist. “The religion of workers has no God because it seeks to restore the divinity of man” (letter to Hartmann); it is the (positive) vision of human beings as the producers of their own history which guides the (negative) critique of alienation. One cannot overestimate the importance of the texts in the Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts: here we see the critique of religion, complete in its principle, seeking its economic base. It is the production of the human being by a human being that renders the idea of creation unacceptable: “But since for socialist man the whole of what is called world history is nothing more than the creation of man through human labor, and the development of nature for man, he therefore has palpable and incontrovertible proof of his self-mediated birth, of his process of emergence.”2 Man’s ability to recover what has been lost makes God’s existence superfluous.

But already, this text introduces the feature specific to Marx: the interpretation of man as worker and, as such, as the producer of his own existence: this is where the alienation stemming from Hegel and Feuerbach begins to be placed in an economic and social situation.

We can thus, already at this period, speak of materialism; Marxist materialism is prior to the theory of class struggle; it signifies that alienation stems from the material existence of human beings and extends up to their spiritual existence. But materialism takes on substance when the relation of spiritual life to material life is conceived in close connection to the idea of “reflection.” The German Ideology is a critical witness here: it is Marx’s most materialist text. Ideas “are continually evolving out of the real life-process.”3 The nature of individuals must be found “not as they may appear … but as they actually are, as they act, produce materially.”4 Ultimately, it must be said that “There is no history of politics, law, science, art, religion”: “such is the true materialism of real society.”

This materialism seeks to make itself scientific through a history of “money”: in texts prior to the Manifesto, money is already the instrument of the material alienation of human beings; to understand its mechanism is already to overcome alienation (se désaliéner). A new critique is thus born, which is no longer a critique of consciousness by consciousness, but a real critique of real conditions. The sharpest thrust of this critique is the last of the Theses on Feuerbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways, the point is to change it.”

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts sum up the situation well, in calling for “the positive suppression of all estrangement [alienation], and the return of man from religion, the family, the state, etc., to his human, i.e. social existence.” The text continues: “Religious estrangement as such takes place only in the sphere of consciousness, of man’s inner life, but economic estrangement is that of real life – its supersession therefore embraces both aspects.”5

Why speak of a Marxist nebula with regard to these texts? Because materialism can receive several meanings. This materialism is not a materialism of things, but a materialism of human beings. Better yet, a realism: the fact that the individual is a “producer” underscores that she is not nature, animality; moreover, the individual does not “produce” simply to live, but to become human and to humanize nature. Nature itself appears as the “inorganic body of the individual.” Work thus becomes more than an economic category: through work, people express themselves, grow, create. Through work, it would seem that Marx is pursuing a dream of innocence: the reconciliation of the human being with things, with others, with the self – reintegration “at home” (chez soi).

This is why human alienation is itself always more than economic; it is the total dehumanization of the individual. “What the product of his labor is, he is not.”6 Marx knows what this means for the individual, producing himself as merchandise, before understanding the mechanism of surplus-value. Alienation is scandalous precisely because “Labor is the only means whereby man can enhance the value of natural products, and labor is the active property of man … [and] the only constant price of things.”7 One does not see how this description can be given without an expression of indignation, a properly ethical moment of evaluation: “The devaluation (Entwertung) of the human world grows in direct proportion to the increase in value (Verwertung) of the world of things.”8

However, if Marxism, in its beginnings, is more than economic, on what level is it to be situated? Is it philosophy? Sociology? It seems to me that Marxism created a mode of thinking that is to scientific economics what phenomenology is to psychology. There is perhaps no mechanism for which Marx would truly be the inventor. To borrow Father Bigo’s expression, “Marxism is not the explanation of a mechanism, but an explanation of existence.” Marx’s science

does not aim at eliciting empirical laws and finding better forms of organization. It takes capital and value as situations in which human beings find themselves, and it sets for itself the task of showing the deep contradictions they contain. Marxist science – lengthy analyses would be necessary to make acceptable this idea which is, at first glance, disturbing – is actually a philosophy of man, a meta-physics of the subject, more precisely a meta-economics of capital and value.9

It is because this is a meta-economics that the Hegelian law of contradiction and reconciliation could be taken up in a dialectic of real human beings. Humanity’s movement then appears as the passage from unity without distinction (archaic communism) to the economy of classes, which is the antithesis of the preceding thesis. The synthesis is thus a return to the thesis, but by means of “negation”: from the class-based economy, the technology is retained but the exploitation is suppressed. This sort of overview escapes empirical verification. It is rather a matter of illuminating by the totality of history each of its moments; the grasp of this totality includes at one and the same time a sociological forecast, a judgment of economic and ethical value, and a maxim of action.

By the same stroke, the exploitation of man by man that introduces the “negative” is neither a moral evil nor an external fate; it is not a dialectic external to the human being, a mechanical determinism, but a movement of the human being as such: “the whole of what is called world history is nothing more than the creation of man through human labor.”10