28,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

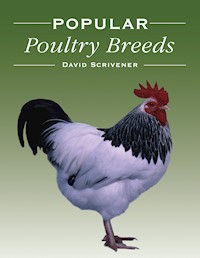

Popular Poultry Breeds examines forty mainstream breeds of chickens and bantams divided into thirty-five chapters. Most breeds exist in several plumage colour varieties, and in large and bantam (miniature) size versions, all of which are also included in this comprehensive book. Detailed histories of each breed are given, in many cases including the names of the breeders and where they lived. Also, the special management and selective breeding requirements needed for certain breeds is studied, even if they are not going to be entered into shows. The book includes helpful descriptions of the breeds, and is beautifully illustrated in full colour with over 180 photographs of prize-winning birds and nearly ninety reproductions of exquisite old prints of artist's drawings. This painstakingly researched reference work is aimed at smallholders, hobbyist poultry keepers, serious enthusiasts and those researching chicken breeds.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 521

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

First published in 2009 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2015

© David Scrivener 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 971 1

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Mrs Joyce Tarren for allowing me to buy her late husband's collection of photographs, over 180 of which are reproduced in this book; and to Fred Hams and Andrew Sheppy for help with details of some breed histories.

Contents

Introduction

1. Ancona

2. Araucana, British, Rumpless and Ameraucana

3. Asil (formerly Aseel)

4. Australorp

5. Barbu d’Anvers (Antwerpse Baardkriel or Antwerp Belgian)

6. Barbu d’Uccles/Ukkelse Baardkriel/Belgian d’Uccle

7. Barbu de Watermael/Watermaalse Baardkriel

8. Barnevelder

9. Brahma

10. Cochin

11. Dorking

12. Dutch Bantam/Hollandse Kriel

13. Faverolles

14. Hamburgh (UK)/Hamburg (USA)/Hollandse Hoen (Netherlands)

15. Indian Game (UK)/Cornish (USA)

16. Japanese/Chabo Bantams

17. Leghorn/Italiener

18. Malay

19. Marans

20. Minorca

21. Modern Game

22. New Hampshire Red

23. Old English Game, Carlisle and Oxford types

24. Orpington

25. Pekin and/or Cochin Bantam

26. Plymouth Rock

27. Poland or Polish

28. Rhode Island Red and Rhode Island White

29. Rosecomb (UK, USA)/Bantam (Germany)/Java (Netherlands)

30. Sebright Bantam

31. Shamo, Ko-Shamo and Relations

32. Silkie

33. Sussex

34. Welsummer/Welsumer

35. Wyandotte

Bibliography

Index

Introduction

This is intended to be a companion volume to Rare Poultry Breeds, which should explain any apparent omissions or inconsistencies in the breeds covered. There are references to some ‘rare breeds’ where they were involved in the development of ‘popular breeds’, mainly some now extinct American breeds, which had to be mentioned again in the histories of Plymouth Rocks, Rhode Island Reds and Wyandottes.

‘Bantams’. Like many of the illustrations in this book, this picture comes from a print that was originally a free gift with a magazine, in this case Feathered World magazine, 2 March 1928. Artist: A.J. Simpson

Fortunately a lot of detailed information was documented, during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, on the origins of the breeds covered in this book. In most cases it has been possible to give names and details of key individuals. In the case of some very ancient breeds, Dorkings for example, although their early history was never recorded, changes made to them in the Victorian era are known. Poultry shows, and the publication of detailed breed standards for show judges to go with them, stimulated most breeders to selectively breed for specific plumage patterns, comb shapes and so on, more than they had before.

In addition to the historical content, there are also some details of the main difficulties in breeding perfect specimens, and how to overcome them. Another of the author’s books, Exhibition Poultry Keeping (also published by the Crowood Press) covers breeding and showing techniques, including ‘double mating’ in much greater detail. It did not seem sensible to duplicate too much.

Most of the breeds included in Popular Poultry Breeds are also kept by many hundreds, in some cases thousands, of hobbyists all over the world. In some cases their breed standards are noticeably different from one country to another. These differences have been fully covered, and it is hoped that breeders in one country will be interested by the fact that their champion birds would not even be recognized by breeders and judges elsewhere.

CHAPTER 1

Ancona

Ancona is a city on the east coast of Italy, from which the first recorded shipments of chickens arrived in England in about 1850. Among the first importers and subsequent exhibitors were Mr Simons and Mr John Taylor. The latter, who lived at Cressy House, Shepherd’s Bush, London, was also a leading early breeder of Andalusians. For most of the century-and-a-half since then, Anconas have been universally recognized as a single plumage colour breed, black with small white tipping. This was not the case in the first few decades of the changes from simply being local laying hens to being an internationally recognized ‘proper’ breed. Readers should be aware that in the 1850s, although some birds had already been taken from the west-coast port of Livorno to the USA, the Leghorn breed had not yet been properly established. In addition to the expected ancestors of the present Ancona breed (birds with variations of black-and-white mottling from neat spotting to random markings like the later Exchequer Leghorns), there were also Black-Red/Partridge and Cuckoo barred ‘Anconas’. The then local name for black-and-white plumaged birds was ‘Marchegiana’, the name of a nearby district. However, even these varied, some coloured as Spangled OEG or a white-spotted variation of Duckwing Game.

Anconas. Originally a free gift with Poultry magazine, circa 1912. Artist: J.W. Ludlow

Although they were good layers, their varied appearance led many authorities in the world of poultry keepers to write them off as mongrels for many years. This attitude started to change when Mr A.W. Geffcken of Southampton obtained a fresh importation of more uniformly coloured Anconas in 1886. These were all black with white spots, although the white markings were not yet as neat and tidy as they would become. They also had the present shank/foot colour of yellow with black spots. Over the following decade Mr Geffcken, and subsequently his customers, spread them around the country. Mrs Constance Bourley of Frankley Rectory near Birmingham was a particularly enthusiastic Ancona breeder of this period, who was quoted in the livestock Journal Almanack of 1895 and in Wright’s Book of Poultry praising their hardiness, activity and laying ability on her wet, windswept hilltop farm. She said most other breeds she had tried had sickened and died there, with the survivors laying very few eggs. In contrast, Anconas kept themselves warm by foraging around the fields, even when there was snow on the ground. No doubt she would have been one of the founder members when the Ancona Club was formed in 1898. Some Ancona Club members concentrated on tidying up their plumage markings, in response to the very generous show prize money and high sale prices of potential winners then. However, Ancona Club members were aware of the dangers of separate exhibition and utility types developing, as happened with some other breeds. The Club agreed a joint breed standard with the National Utility Poultry Society in 1926 to avoid this.

Mrs Bourley’s praises of Anconas as active layers in free range conditions were confirmed by hundreds of other small scale poultry keepers through to the 1950s, but they were also rather wild and nervous. These were valuable survival instincts in free range flocks, which could get safely up a tree when foxes were on the prowl, but less welcome with larger scale commercial egg producers. Several such producers gave up Anconas during the 1920s because they could not be tamed when kept in laying flocks of 100 to 1000 in deep litter houses, with or without outside runs (normal commercial conditions then), without birds being lost by panicking. A Mr Messenger reported in 1921 that fifteen glass windows were smashed by a flock of 150 Anconas over a three-week period, despite their attendant being a quiet and elderly man with a lifetime of chicken-keeping experience.

Most Anconas have always been single-combed, but a rose-combed variety was bred by crossing with Hamburghs and Wyandottes, the latter type predominating. These first appeared about 1902–5. Eventually, say by 1930, the only difference was the comb; but up to about 1920 rose-combed Anconas were noticeably heavier and more docile than single-combed Anconas. They were made to cope with cold climates, as large single-combed chickens can suffer from frostbite. There was a separate Rosecomb Ancona Club in the UK, 1923–26.

Francis A. Mortimer of Pottsville, Pennsylvania, was the first to import Anconas to America from England in 1888. He bred and sold several batches before his death a few years later. One buyer was Mr H.J. Branthoover of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, who was so impressed that he arranged further importations from Mrs Bourley. Mr Branthoover promoted them, becoming President of the Ancona Club of America, formed in 1903. The club grew from thirteen founders to over 400 members by 1912, but then declined as White Leghorns became the only breed used in America for commercial egg production.

Ancona Bantam

Mr Endson exhibited a team of Ancona Bantams at the 1912 Dairy and Crystal Palace shows, the first mention of them found by the author. Another leading breeder of them was Robert W. Tunstall of Leyburn, Yorkshire. He claimed to have made them from successive generations of ever smaller undersized large Anconas, without crossing with other bantam breeds. However, photos of Ancona Bantams in the 1920s show muscular birds with rather small tails, indicating some breeders had tried crosses with Spangled Old English Game Bantams. Mr D. Dennison was showing rose-combed Ancona Bantams in 1929.

During the 1930s the largest displays of Ancona Bantams, even at major shows, were about twenty birds, Mr Tunstall usually taking most of the prizes. They became more popular after the war, as indicated by an entry of twelve males and twenty-five females at the 1954 National Show at the Olympia exhibition hall, London. The 1962 event in the same hall had an impressive display of sixty-nine Ancona Bantams in six classes (cock, hen, cockerel, pullet, novice male, novice female). Entries at major UK shows in recent years (2000–2007) have been typically about fifty birds.

Mr W.L. Marr of Narembum, New South Wales established Ancona Bantams in Australia. He imported some hatching eggs from Gerald Gill of Kent, England in 1946, just before the Australian government banned all importations of livestock and hatching eggs. Unfortunately only one cockerel was successfully reared from these eggs, but another Australian fancier, Joe Saul, had already started to make a strain by selecting from the smallest available large Anconas. Thus Ancona Bantams were established in Australia from the imported cockerel and ‘half size’ pullets from Mr Saul. Mr Marr noted (in the 1980 Bantam Club of N.M. Yearbook) that other Australian fanciers had also tried crossing with Spangled OEG Bantams, resulting (as in the UK) in Ancona Bantams with rather small tails, some of which (unusually for Mediterranean light breeds) went broody.

ANCONA DESCRIPTION

For full details consult British Poultry Standards, the American Standard of Perfection or their equivalents in other countries. General body shape is similar to other Mediterranean breeds, perhaps more compact and meatier in body and a little shorter in leg and neck than their relations. Large fowl weights range from 2kg (4½lb) pullets up to 3kg (6½lb) adult cocks. The equivalent bantam weights are 510g (18oz) and 680g (24oz). Most specimens appear to be of approximately correct weight.

Ancona, large male. Photo: John Tarren

Single combs should be of medium size, upright on males, flopping over on females. Some females have rather small, straight combs, which could be helped by keeping pullets in warm houses for a few weeks before showing. The opposite problem is often seen on the rarer rose-combed variety; they often have rather coarse, poorly shaped combs. A neat rose comb, of Wyandotte type with the leader close to the skull, is the ideal. Cool conditions, with access to outside runs, help to limit comb growth. Remember that combs are heat-losing organs. Ear lobes should be medium sized, oval and white. Anconas allowed out on grass sometimes have a yellowish tinge, which is not considered a major fault by most judges, unlike partly red lobes, which are more serious. Eyes are orange-red. The beak should be yellow with black or horn shadings, to match their shanks and feet, which are yellow with black spots.

Ancona, large rose-combed female. Photo: John Tarren

Plumage is glossy greenish-black with neat white, V-shaped tips on enough of them to give the impression of even markings. A white tip on every feather would be too much. The white tips get larger and more numerous with each moult after they reach maturity. Novice Ancona breeders should be aware that their juvenile plumage is nothing like the adult pattern; instead they have a penguin-like arrangement of white breast and black back and wings. Very few Anconas are still showable by the time they are three years old, although some that were almost completely black in their first year, might come into their prime. The black pigment should extend down to the skin, some faulty specimens having a light undercolour. Excessive white in plumage is most likely to be seen in main wing and tail feathers. A new Blue-Mottled variety has, so far (2008) only been seen in Germany and the Netherlands.

Ancona, bantam female. Note rather small tail, a legacy from the Spangled OEG Bantams used to make Ancona bantam strains circa 1920. Photo: John Tarren

CHAPTER 2

Araucana, British, Rumpless and Ameraucana

As far as the scientific community was concerned, South American blue-egg laying chickens were first discovered by Prof. Salvadore Castello in 1914, which he made known to the general public in 1921 at the first World Poultry Congress at Den Haag (The Hague), the Netherlands. In fact, European explorers had recorded blue chicken eggs in South America as early as 1520.

Araucanas. Artist: Cornelis S. Th. van Gink

Rumpless Araucanas. Artist: R. Hoffmann

Despite being four centuries behind their real initial European discovery, Prof. Castello’s rediscovery is a significant part of the history of Araucana chickens, so is as good a start to this chapter as any.

Prof. Castello was Director of the Royal Spanish Poultry School, Arenys De Mar, Barcelona. His duties included advising and lecturing on poultry farming in several Spanishspeaking South American countries. On one such trip, on 6 August 1914, he noticed a lot of blue eggs for sale in the market of Punta Arenas, a city at the southern end of Chile. He also saw the chickens who laid them, which were rumpless, had small single combs, many of them being white or pile in plumage colour. He was told they were called ‘Colloncas’, and that local people had a vocabulary of poultry-keeping words, completely different from equivalent Spanish terms. Thus there were three unusual features: blue eggs, rumplessness and local linguistics, all suggesting they might have existed in South America for a very long time.

Although nominally a Chilean breed, Araucanas were found in many parts of South America. Ferdinand Magellan’s expedition across the Pacific from the Philippines recorded them on the west coast (now Chile) in 1520, but so did Sebastian Cabot, who found blue-egg laying chickens on the east coast (now Brazil), on his expedition which had started from Bristol.

Moving on a few centuries, one wonders why British poultry experts in the nineteenth century had not investigated the matter, as they are clearly described in Bonington Moubray’s book A Practical Treatise on Breeding, Rearing and Fattening all kinds of Domestic Poultry (various editions, 1815–1842). ‘In addition, there is a South American variety, either from Brazil or Buenos Aires, which will roost in trees. They are very beautiful, partridge-spotted and streaked; the eggs small and coloured like those of the pheasant; both the flesh and eggs are fine flavoured and delicate.’ (‘Buenos Aires’ because the state of Argentina did not exist then.)

The chickens were named after the Araucano tribe of Native South Americans, one of the few on the continent who were warlike enough to survive in large numbers as Spanish immigration increased over the centuries.

When the scientific community was made aware of the sixteenth-century references to them being bred in large numbers in many parts of South America, clearly having been there long before Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492, they were faced with a mystery. Domestic chickens were known to be mainly descended from Red Jungle Fowl, with some contributions from the other three species of Jungle Fowl, all of which live in south and east Asia. It was then also thought that all Native Americans came across from northern Asia, Siberia to Alaska (to use current place names) when they were connected, before chickens were domesticated. There have been many suggestions of answers to this riddle, including the domestication of now extinct wild South American species, as none of the living Galliformes, Curassows and Guans are likely candidates.

Recent discoveries have confirmed one of the other suggestions made since the 1920s, that chickens were brought across the Pacific, island by island, by another group of early Native Americans, Polynesians, in ancient times. Chicken bones have been found in South America by palaeontologists which have been dated to a century before Christopher Columbus arrived. There will no doubt be more such discoveries, which will be found to be older.

Rapanui (also known as Olmec) fowl also lay blue eggs, and are found on Easter Island (called Rapu Island locally), Pitcairn and other Polynesian islands. As these are more remote than most places on earth, these are likely to be as near to the ancient ancestors of Araucanas as it will be possible to find.

As blue-egg laying chickens were found in many parts of South America, and were ‘just chickens’ to the people who kept them, it is not surprising that they vary in appearance. Since 1921 there has been quite a lot of argument among American and European poultry experts on the question of what ‘a true Araucana’ should look like. The matter was confused by Prof. Castello who, to be fair to him, was misled about the origin of the birds he first obtained. These laid blue eggs, were rumpless, pea-combed, and had very unusual tufts of feathers growing out from near their ears, which soon became popularly known as ‘ear rings’. This type, which was said to be known locally as ‘Collonca de Artez’, eventually became the standard type of rumpless exhibition Araucanas around the poultryshowing world.

They had been supplied to Prof. Castello by Dr Reuben Bustos of Santiago University, who confessed to Prof. Castello after the 1921 World Poultry Congress that they were the result of crossing two different breeds Dr Bustos had discovered many years earlier. Prof. Castello explained the mistake at the next World Poultry Congress in 1924, but it was too late; poultry enthusiasts had taken to the 1921 description of Araucanas, and they still choose not to change the standard to avoid its inherent problems. Embryos with two ear-tuft genes never hatch, and some of those with only one ear-tuft gene have head deformities.

Dr Bustos found his two original breeds when in the Chilean Army in 1881. The Colloncas, the blue-egg laying rumpless type, were in the village of the Araucano chieftain Quineoa. Being rumpless was considered an advantage, as predators had difficulty catching them. The other type, called ‘Quetros’ locally, were found in another village, the chief of which was Michinues-Toro-Mellin. These birds were tailed, had ear rings, and laid brown eggs. They were popular with the villagers because the cocks had a peculiar crow, possibly a result of the ear-tuft gene affecting their larynx. ‘Quetros’ apparently translates as ‘laughing hens’, the sound they made said to resemble human laughter.

Many of the originals had single combs and beards, both now counted as show disqualifications. It was later found that pea comb is associated with blue eggs, both being close together on the same chromosome. Some Colloncas already had pea combs, but as many of the birds made available to American and European fanciers came from Dr Bustos’ stock, they nearly all had pea combs. A few single-combed, and a lot of bearded, rumpless Araucanas still appear. There are also a lot without ear tufts, which will always be the case because of its semi-lethal nature. If show birds, with good ear tufts on both sides, are mated together, few chicks will hatch, but birds with no/only one/small ear tufts can be bred with winners for best possible results.

Black-Red Rumpless Araucana, large male. Photo: John Tarren

Dr Bustos crossed the two breeds simply because he was intrigued by the two unusual characteristics of ear tufts and rumplessness, and (unfortunately, as it turned out) decided to try to combine both on one bird. Surprisingly, he thought blue eggs were only ‘quite interesting’, and he never really concentrated on preserving this characteristic. Despite trying for over thirty years (1881–1914) he had not stabilized ‘Collonca de Artez’ as he imagined them.

There were few shipments of Araucanas from Chile to the USA over the following years, and they were featured by John Robinson in his book Popular Breeds of Domestic Poultry, which, as it was published in 1924, must be the first widely available (apart from scientific works) poultry book to include Araucanas, although Mr Robinson had described them in the November 1923 issue of Reliable Poultry Journal (the magazine also published the book). The book has three photos of Araucanas; one shows a pair with single combs, no ear tufts and coloured ‘same as Brown Leghorns’. The other two photos show a young Pile cockerel and a White pullet, both with well formed ear tufts. They seem to have small single combs, but as they are both immature, they could have been pea combs. Other Americans imported tailed blue-egg layers, and there were many arguments between groups of fanciers, spanning several decades, which greatly delayed Araucanas being standardized in the USA.

White Rumpless Araucana, large female. Photo: John Tarren

The poultry fancy in the USA has two governing bodies, the American Poultry Association and the American Bantam Association, which say in public that they work in harmony, although this may not have always been true. The ABA first standardized Araucanas in 1965, recognizing tailed and rumpless types, with or without ear tufts, perhaps in an attempt to satisfy rival breeders. These standards were, of course, only for bantams. The APA called interested parties to their APA Convention, at Pomona, California in 1975 to clarify matters. The APA decided to only recognize the pea-combed, ear-tufted, non-bearded, rumpless type in 1976. The ABA decided to cut down to just this type in 1983, when they were trying to harmonize with APA standards.

However, all was not lost for tailed Araucanas; they were to be standardized under a new name, the Ameraucana. These more convential looking chickens, along with the broadly similar British type Araucana (see below), are both reasonably representative of blue-egg laying chickens as they had been bred for centuries all over the rest of South America. Rumpless ‘Colloncas’ were probably a speciality of southern Chile.

AMERAUCANA

Harry Cook of New Jersey is mentioned by the Ameraucana Breeders Club as a pioneer breeder of bearded and tailed Araucanas since before 1960, although he was not alone, as there was a short-lived American Araucana Breeders Association which tried to support tailed Araucanas after the APA’s decision in 1976. Don Cable of Orangevale, California, Mike Gilbert (Iowa in 1977, later Holmen, Wisconsin) and Jerry Segler, Illinois took up the cause of tailed Araucanas, forming a provisional (then unnamed) club in 1978 with eleven scattered founder members, including Dorian Roxburgh, then Secretary of the British Araucana Club.

The name Ameraucana was preferred by the majority of the founder members over the other proposed alternative: American Araucana. A provisional standard, initially just for bantams, was written in 1979, when the new club had twenty-eight members. Only bantams were standardized initially because the ABA was usually more willing to accept new breeds than the APA. Ameraucana Bantams were presented at the ABA at Pleasanton, California in November 1979, and were recognized by the ABA in May 1980. The APA accepted large Ameraucanas in 1984, requiring a name change, from Ameraucana Bantam Club to Ameraucana Breeders Club.

BRITISH ARAUCANA

Araucanas seem to have been first brought to the UK in enough numbers for many people to notice in 1930, no doubt including a fair number brought for the World Poultry Congress at the Crystal Palace that July. There were certainly some here earlier, however, including some bought by Ian Kay’s father in about 1920 from someone who brought some eggs back from Peru. These were Black-Red Partridge, and the strain was kept going by Ian until about 1970.

Mr F.C. Branwhite, of Often Belchamp Hall, Clare, Suffolk, wrote an article about them in the 1932 Feathered World Yearbook. As well as an early UK Araucana breeder, he was also one of the last known people with Yorkshire Hornets. His Araucanas were imported from the USA, and were Black-Reds, with pea combs and green shanks and feet. The article has photos of a male and a female, taken by Arthur Rice. Mr Branwhite preferred red ear lobes, but the cockerel photographed had white lobes. His males weighed 2.7kg (6lb), females 2.5kg (5½lb).

The 1935 Feathered World Yearbook had an article on Araucanas by Miss V. Barker Mill, with photos of birds owned by Mrs Whiteway, of Exmouth, Devon, ‘who has kept Araucanas for some time’. These birds were similar to Mr Branwhite’s.

Another early breeder of Araucanas obtained indirectly from the USA was Mr Ernest Wilford Smith of Great Glen, near Leicester, who bought Black-Reds with single combs from George Beaver, a salesman who had been to America. Mr Smith still had Araucanas when he died, aged 89, in May 1994, that were latterly cared for by a neighbour, Richard Billson, Rare Poultry Society Secretary for many years, then President.

Lavender British type Araucana, bantam female. Photo: John Tarren

Apart from American stocks, much of the stock which eventually became British type Araucanas (tailed, bearded, crested, and often with Lavender plumage) came to the north of Scotland and the Hebrides. A Chilean nitrate (fertilizer made from dried seabird droppings) ship foundered on the coast somewhere in this area during the thirties, and Araucanas on board became established in the Hebrides from then on. More blue eggs, some of which were incubated, were brought to Scotland from South America in the early years of the Second World War. A club, the Araucana Society of Great Britain, was formed in 1956. Its secretary was Mrs Main, of Turriff, Aberdeenshire, who bred a great many birds (by hobbyist standards), and must be remembered for keeping them going when Araucanas almost died out about 1945. She and the other members, who despite the ‘Great Britain’ title were almost all in the north of Scotland and the Scottish islands, adopted beards and crests as their ideal because many of the original birds had them, so it was assumed these features must be correct. Unfortunately, for reasons which are not entirely clear, the ASGB chose not to become involved when English breeders tried to get Araucanas standardized by the PCGB in the 1960s. The ASGB existed until 1985, but never affiliated to the PCGB. This situation could not continue, so English Araucana breeders joined the Rare Poultry Society when it was formed in 1969 (many also had other rare breeds, so were members anyway) as a first step, before they formed a new British Araucana Club, covering the whole of the UK, in 1972.

Duckwing British type Araucana, large female. Photo: John Tarren

One long-time Scottish Araucana breeder deserves special mention: George Malcolm, of East Lothian. He started to make Araucana Bantams about 1945, using Belgian Bantams to cross with undersized large Araucanas. Some of the Belgians must have carried the Lavender gene, although it is not known whether they were Lavender Quail, Barbu d’Anvers or Porcelain Barbu d’Uccles. The result was the Lavender British type Araucana, which has remained the most popular variety of the breed ever since. Large Lavenders were made much later by a Mr Edwards, address unknown, who crossed Crested Legbars with other colours, also unknown, of large Araucanas, possibly Blacks.

The British Araucana Club also supports Rumpless Araucanas, but there have never been many breeders of them in the UK. British type Araucanas have been bred in much greater numbers than the number seen at shows would suggest; however, a lot of regular exhibitors keep some for showing their eggs. Here are a few examples of entries at British Araucana Club Annual Shows, which illustrate the gradual increase in the colour varieties kept:

1978 National Show: 15 large (mostly Lavenders), 18 Lavender bts, 5 AOC bts, 9 Rumpless

1990 National Show: 13 large Lavender, 14 large AOC, 0 Rumpless, 28 Lavender bts, 9 Black bts, 6 AOC bts

2004 National Show: Large: 15 Lavender, 9 Black-Red, 15 Black, 15 AOC, 14 AC young-stock. Bantam: 17 Lavender, 5 Black-Red, 11 Black, 18 AOC, 15 AC youngstock. Rumpless: 8 large, 8 bantam.

(Rumpless Araucana Bantams were a recent arrival in the UK then, see below for details.)

RUMPLESS ARAUCANA DESCRIPTION

For many years there was only one size of Rumpless Araucanas, a smallish large fowl, but now we have a bantam version; which will no doubt encourage breeders to try to increase the size of their large birds. The British Araucana Club Rumpless standard weights have been 2.7kg (6lb) males, 2.25kg (5lb) females for a long time, although it is highly unlikely that any have ever appeared at a UK show up to these weights. Weights given in the Netherlands’ standards are much more realistic for the majority of Rumpless Araucanas bred worldwide over the last fifty years or so: 1.8–2kg (4–4½lb) males, 1.4–1.6kg (3–3½lb) females. German standard weights represent an achievable target: 2–2.5kg (4½–5½lb) males, 1.6–2kg (3½–4½lb) females.

Rumpless Araucana Bantams were made by two German fanciers, Friedrich Proebsting, of St Augustin–Meindorf, and Hubert Voßhenrich, of Schloss Holter, circa 1965–75. They were made by crossing smallish large Rumpless Araucanas, Dutch Bantams and Zwerg-Kaulhuhn (German Rumpless Bantams, similar to UK Rumpless Game Bantams but less ‘gamey’). Standard weights are 750g (26oz) males, 650g (23oz) females. Most are bigger and heavier than this, nearer 900g (31oz) and 800g (28oz).

Rumpless standards in all countries require pea combs, ideally small and compact, although many have rather high and floppy combs. Fanciers have to cope with the genetic problems of ear tufts as best they can. Laws have been passed in some countries prohibiting the breeding of livestock with harmful characteristics, which may affect Araucana breeders in future. Such laws, however well intentioned, may unfortunately cause the extinction of some historic breeds of livestock, but as Rumpless-Tufted Araucanas seem to have been a mistake in the first place, it is not a great concern. Beards on Rumpless Araucanas are required in some countries (such as the UK), a disqualification in others (such as the USA), and tolerated in the rest.

The main colour varieties seen around the world are variations of Black-Red, with Partridge, Wheaten or ‘in-between’ females. The standards in some countries only allow one type of female plumage, but evidence suggests some latitude would be more historically correct. Blue-Reds and Duckwings are also seen, again with historical evidence suggesting a range of female colours should be allowed. There are also Blacks, Blues, Cuckoos and Whites. Piles are not included in the standards of Rumpless Araucanas in many countries, but have been known since the 1920s, so perhaps some of the breed clubs should review this variety.

BRITISH ARAUCANA DESCRIPTION

While still a light breed, these are a good sized utility breed. There are some undersized birds around, but many are well up to standard weights of 2.7–3.2kg (6–7lb) males, 2.25–2.7kg (5–6lb) females. Bantam standard weights are 740–850g (25–30oz) males, 680–790g (24–28oz) females. As is often the case, quite a lot of bantams are above these weights, but oversized bantam pullets are still very saleable as pet blue-egg layers.

General body shape is similar to many light-to-medium type breeds, as can be seen in the photos. Their most characteristic features are on their heads: a pea comb, compact crest, and beard. Walnut combs have been common over the years, but are a show disqualification.

The most popular colour variety is the Lavender. Good females are not too difficult to breed, but many males have yellow (or ‘straw’) neck and saddle hackles. Bright sunlight worsens this fault, so runs under the shade of trees are ideal for show birds. Other self colours are Blacks, Blues and Whites. There are also Cuckoo British type Araucanas.

Black-Reds, Blue-Reds, Gold-Duckwings, Silver-Duckwings, Creles, Piles and Spangles are all standardized, in all cases with the relevant Partridge-based female colour pattern. This is no doubt why some Club members have been reluctant to accept wheaten females on Rumpless Araucanas: they have not fully understood the differences in origins of the two types.

Blue-Red large Araucana male. Photo: John Tarren

AMERAUCANA DESCRIPTION

General body shape and type is similar to British type Araucanas, with slightly lower standard weights. The most noticeable difference is that Ameraucanas do not have a crest.

Standardized self-colour varieties are Black, Blue, Buff and White. There are no Lavender Ameraucanas. The patterns are a rather difficult to understand list: Black-Red/Wheaten, Blue-Red/Blue-Wheaten, Brown-Red, Silver Duckwing. The last named apparently with salmon-breasted (that is, a silver version of partridge pattern) females. Considering the other varieties, one would have expected Silver-Wheaten (as Salmon Faverolles) females.

Large Araucana Pile cock. Photo: John Tarren

CHAPTER 3

Asil (formerly Aseel)

The name Asil is derived from an Arabic word meaning pure, or of long pedigree. Similar birds were described in Indian documents written over 3000 years ago, which probably makes Asil the most ancient poultry breed. The name has been applied to fighting cocks across much of Asia. Some regional types, especially in the north-western part of this range, were somewhat larger birds, which have now been standardized for showing in the UK as ‘Kulang’ or ‘Kulang Asil’. They are rare here, and are a recent addition to UK poultry shows, so have not been considered in this book. The smaller type of Asil has never been popular in the UK, but there has been a steady succession of enthusiasts since the first specimens were brought to England in the seventeenth century. They have been shown here, in modest numbers, since Victorian times.

Asil. Artist: F.W. Perzlmeyer

Although there is some variation in size and shape between the larger Kulang type and the smaller versions of Asil, they have enough common features to support their relationship. All have hard, scanty plumage, usually showing bare red skin along the breastbone, on their wing joints and around the vent. Tail feathers are almost straight on males, and carried at or below the horizontal. All types have a powerful skull and beak, a long, very muscular neck, minimal wattles and a small pea or walnut comb. These features have been developed to suit them for their original purpose, ‘naked-heel’ cockfighting. This is the type of cockfighting where artificial steel or silver spurs are not used, instead the cocks are left to fight with the tools nature, and a lot of selective breeding, has provided. Cockfights with artificial spurs were sometimes over in under a minute, but naked-heel fights could last an hour or more. Naked-heel fights did not always end in the death of the loser, as one bird might ‘run’. Naked-heel cockfighting enthusiasts have long said, with some justification, that unlike the quarry animals in all forms of hunting (including fishing), game cocks fight because they want to. They may be in an enclosure (‘pit’), but if one cock ran, that was it, end of contest. Within the social context and mores of those times, all forms of cockfighting were bound by strict rules and conventions, so were not the scenes of bloodlust most people imagine.

The type of Asil mainly bred and exhibited in the UK and elsewhere since the 1860s were based on the type bred in the Mughal kingdom of Oude (or Awadh) in northern India, around Lucknow, circa 1670 to 1870. This region was a ‘puppet’ kingdom for many years under British colonial rule. Some other regional types, such as those traditionally bred around Calcutta, were not too different, and were no doubt added to the stocks brought to England by British army officers and colonial civil servants when they came back on leave or at the end of their time in India. Captain Spencer Astley was one such, employing a dozen Indian servants to look after his Asil until he retired to England in 1898. Another was Charles F. Montresor, who was given a Black Asil hen by the (then) ex-king of Oude. Another was Herbert Atkinson, a wealthy artist who spent summers at his home in Oxfordshire, and winters in India until his death in 1936. An Asil Club briefly existed during the 1890s, and he was its secretary. Robert de Courcy Peele, of Ludlow, Shropshire, was secretary of the Aseel Club (the spelling used then), when it was reactivated for a few more years, circa 1909–22.

All of the above had seen Asil in India, so were occasionally upset by some of the birds bred and given prizes by fanciers and judges at British shows by those who were not so well travelled. It was suspected that some had been crossed with Indian Game/Cornish, as they had puffy cheeks and were too meaty, especially on their back (over their hip joints). The two most popular plumage colour varieties with these exhibitors and judges were Spangles and Whites. Those who had been to India had seen these colours there, but knew that Indian breeders thought they were not as good as various shades of Black-Red cocks (a few white feathers were not considered a problem) and hens which normally ranged from Black, via ‘Grouse’ or ‘Pheasant’ (‘messed up’ variations of the Dark Indian Game pattern), to Cinnamon and the darker shades of Wheaten (similar to Malay hens). Other colours seen since the mid-nineteenth century have included Black-Mottles, Duckwings, Greys and Piles. All are permitted, but to most Asil enthusiasts, are seldom as good as Reds. There are a number of splendid looking Spangled Asil, most of which are believed to be from German strains, seen at UK shows; but when handled, most of them have the same fleshy type (possibly part Indian Game) criticized by Atkinson in the 1920s.

ASIL BANTAM

No records have been found on the origins of the first Asil Bantams, which were popular from 1875 to 1900 but then died out. They may have been Ko-Shamo, Chibi-Shamo or Nankin-Shamo which were incorrectly identified by the fanciers who bought them, probably from ships in Falmouth or other ports in south-west England.

Black-Red Asil, male. Photo: John Tarren

Virtually nothing was seen of them, or anything like them, again in the UK until 1975–80. The birds that appeared then – probably from Germany – were very small Black-Red males and Wheaten females. They were incorrectly called Tuzo at the time. We now know Tuzo are a larger breed (halfway between large fowl and bantam size), only recognized in one colour variety, Black. A few fanciers in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK have been working on new strains since the 1990s.

ASIL DESCRIPTION

There are full standards in American, British, Dutch and German Poultry Standards books, so this section concentrates on the key points.

The beak must be short, strong and thick. Its colour can range from ivory or yellow through to very dark horn, almost black; the darker colours are usually seen on Black, ‘Grouse’ and ‘Pheasant’ hens. Correct eye colour is considered an important breed characteristic, the ideal being yellow or white, often with some red blood vessels visible. Young birds usually have darker eye colour, which gradually lightens between 8 and 18 months of age. Asil have neat, small pea combs and no wattles at all. Instead of wattles, the skin of the throat is bright red and bare of feathers some way down the neck. The neck is of medium length and very muscular. The neck hackle feathers of males are short, not covering the shoulders.

Spangled Asil, male. Photo: John Tarren

The correct body shape is distinctive and an important breed characteristic, broad across the shoulders and shallow from the back down to the breast. Some birds seen at shows have been too deep-bodied, suggesting they were not ‘the real thing’. Body plumage should be sparse and close, showing bare red skin along the breastbone, around the vent and on wing joints. The tail should be horizontal or lower, in line with the back. Male tail sickle feathers are fairly straight, sometimes described as sabre shaped. Legs are medium length, with very muscular thighs. Scales on shanks are prominent, giving a ‘square’ appearance. Shanks and feet are usually creamy or yellow; horn, olive or black on dark-plumaged varieties.

There are no fixed plumage colours, but most experts prefer the traditional colour varieties over new colours which might indicate dubious ancestry. Remember the name of the breed means ‘of long pedigree’. Within these conventions, Asil are not judged on fine details of plumage colour. The majority of males are Black-Reds, but it does not matter if there is some red or brown in breast or thighs, or which shade of ‘red’, or if there are some white feathers. Spangles are a traditional variety, as are any birds between Black-Red and Spangled. The comments made previously about some Spangled Asil being suspiciously fleshy do not mean that there are no good Spangles. The hens to go with Black-Red cocks range from ‘Grouse’ and ‘Pheasant’ to ‘Cinnamon’ and ‘Red Wheaten’. The first two have a rich brown ground colour with black peppering (Grouse) or an irregular version of the Dark Indian Game/Cornish pattern (Pheasant). Spangled hens usually have a red wheaten ground colour with variable black-and-white spangles.

Black Asil, White Asil and Pile Asil are seen occasionally, but their plumage colour names should be regarded as a rough guide only. For example, White Asil are usually more or less ‘brassy’. A snow-white Asil (as is expected with other exhibition poultry breeds) would probably be too profuse and soft in plumage to be regarded as a good specimen of this breed. Similarly, Black Asil usually have a few red or brown feathers mixed in; but if its head, body shape and other important characteristics are correct, no one cares. Duckwing and Grey Asil cocks are rarely seen, and the hens to go with them will probably be silver ground coloured versions of Grouse or Pheasant, or Silver Wheatens. Salmon-breasted Duckwing hens (as Duckwing Modern Game or OEG) would be regarded with extreme suspicion.

ASIL MANAGEMENT

Asil are usually bred in pairs, trios or (at most) quartets. Where two or three pullets are together, they will be sisters who have been reared together. When one goes broody, it is seldom possible to put them back together after they have been away sitting and chick rearing. Asil are usually kept in a range of netting-fronted, aviary-type pens. Each pen needs to be about 1.5 × 2 metres (4½ × 6ft) for a pair or group of youngsters. This makes them a very time-consuming breed. The positive side of this is that they usually become remarkably tame.

CHAPTER 4

Australorp

William Cook’s first Black Orpingtons, which he launched in 1886, were quite tight-feathered, much more like Australorps than the much more profusely-feathered Black Orpingtons which were developed by Joseph Partington a few years later, and have been the accepted type of exhibition Orpington ever since. Pictures in his book, W. Cook’s Poultry Breeder and Feeder, clearly show the first Orpintons were like today’s Australorps. Cook’s type were exported to Australia as soon as 1887, with Partington’s type following soon afterwards. Robert Burns, of Sladevale, Warwick, Queensland, kept both types separately for many years: Cook’s for eggs, Partington’s for prizes. SeeChapter 24: Orpington for more details.

Australorps. Artist: C.S. Th. van Gink

One of the key people involved in establishing Australorps as a recognized breed on its own, separate from Orpingtons, was Arthur Harwood (2 June 1887–3 October 1981). He was an Englishman who moved to Australia in July 1910, having previously worked for William Cook’s daughter (after Cook’s death) at St Mary Cray, Kent. He became Chief Poultry Officer at Galton (Agricultural) College, Queensland until he retired in 1938. According to some accounts he coined the name ‘Australorps’ (to replace the long-winded title ‘Australian Utility Orpingtons’) at a poultry farmers’ conference at the college in 1919. The name ‘Australs’ was also in use at the time by several people, including George Greenwood, who was a leading breeder of both utility type and exhibition Orpingtons in Australia. They may have argued over who invented which name, but agreed that Australian fanciers and farmers needed to be educated about the increasing differences between utility and show types. Australian poultry keepers had used British Poultry Standards for Orpingtons, and the British Orpington standard has never been changed to accurately describe the fluffy exhibition type. Some breeders and other experts in Australia opposed the new names, taking the attitude that the published Orpington standard still fitted the utility type. Among these was James Hadlington, New South Wales Government Poultry Expert based at Hawkesbury Agricultural College, Richmond, NSW. Like many poultry experts at the time, he supported pure breeds, even for commercial production. Many commercial breeders were already selecting stock entirely on egg numbers, not caring about plumage colour, and so on. To them a new name meant they could forget breed standards. James Hadlington did not approve, although his strains of ‘Utility type Orpingtons’ (his preferred name) eventually became Australorps.

Significant importations of ‘Australian Black Orpingtons’ to England were made in 1921, and there may have been smaller importations some years previously. The ‘Austral Orpington Club’ was formed in the UK in August 1921, and the name ‘Australorp’ was well known, if not universally used, in the UK, in 1921, with the club’s name being changed to ‘Australorp Club’ in 1924.

Charles Arthur House, editor ofPoultry World magazine (UK) went on a tour of Australia in 1922. In discussions with Australian breeders (who were still arguing about the name), he told them about recent developments in the UK; suggesting they had little choice but to follow suit. Australorps were eventually standardized in Australia in 1930.

British breeders started to discuss standards in 1921, but their first application for recognition by the PCGB in November 1923 was refused because the Council was concerned about the variability of imported stock: some like fluffy Orpingtons, others tighter feathered and smaller. The Australorp standard was eventually passed by the PCGB Council in 1928.

One of the first places C.A. House visited on his arrival was the Western Australia egg laying trial, where over half of the birds entered were utility Black Orpingtons/Australorps, most of the remainder being White Leghorns, very different from British tests, where Black Orpingtons were rare, Rhode Island Reds and Light Sussex being most popular. Australian breeders had certainly improved the laying performance of utility Black Orpingtons since the 1890s. One hen laid a record-breaking 339 eggs in 365 days at the 1912–22 trial at Bendigo, near Melbourne, Victoria. Another batch of six pullets laid 1760 eggs, an average of 291.4 each. A lot more birds were recorded as laying over 280 eggs, and these performances were publicized by UK importers. As soon as they had enough birds, they entered Australorps in British laying trials, with much poorer results, usually nearer 200 eggs, in our colder climate.

Despite the best efforts of the Australorp Club and a few large-scale breeders, they were never as popular in the UK itself as they were overseas, although they were bred commercially and exhibited in fair numbers, such as 81 birds at the 1934 Australorp Club Show at Olympia. Their black plumage would not have helped as cockerels were then reared for the table, and would have left black feather stubs and shanks.

This level of support for Australorps continued through to the early 1960s, after which they gradually declined until the present (2008) situation, where large Australorps are rarer in the UK than some rare breeds. Blue and White varieties have recently been added to the range, and all three varieties are still neat, tidy and attractive birds, but there are plenty of more exotic breeds for hobbyists.

AUSTRALORP BANTAM

Roy Corner of Hereford (Australorp Club Secretary 1930–35) and Jack Mann made Australorp Bantams, first showing them in 1934. No details have been found on how they made them, but we can assume it was by crossing undersized large Australorps with suitable bantams, possibly including Black Wyandottes. They do not seem to have attracted much interest from other fanciers before the war, but their practical qualities during hostilities and food rationing (which continued well into the 1950s) were clearly noticed, although not widely written about. At the 1954 National Poultry Show there was an impressive entry of 43 birds in four classes. They have continued to grow in popularity, with displays of over 100 bantams at the Australorp Club Show being not unusual. Regular exhibitors appreciate that while Black Australorp Bantams might have little appeal to the general public, they are smart little birds, easy to keep and prepare for showing.

Entirely separate strains were made by German fanciers, first exhibited in the new breeds section of the 1956 Hannover Show. More details are known of the breeds used to make them in Germany: large Australorps, Black Wyandotte Bantams, Barnevelder Bantams, Rhode Island Red Bantams and Black German Langshan Bantams. There is a noticeable difference in the back and tail profile of Australorp Bantams in the UK and Germany. In the UK the back/saddle plumage rises in an almost straight line to the tip of the tail, very similar to the top profile of German Langshans. German fanciers have avoided this similarity by selecting a flatter back with a distinct angle at the base of the tail. No doubt they did so to emphasize the difference between the two breeds. German Langshan Bantams have become quite popular in the UK since the 1990s, but were unknown here when Australorp Bantams became popular in the 1950s and 1960s. Photos of large Australorps through the 1920s and 1930s show enough variation to justify both types as true miniatures of the original fowl.

Black Australorp, bantam male. Photo: John Tarren

Blue Australorp Bantams were first made by Alan Maskrey of Sheffield, who started with a Black Australorp Bantam × Blue Orpington Bantam mating. Jack Turton of Ramsgate also started another strain on the same lines, both fanciers beginning about 1973, and having their new colour variety accepted by the Australorp Club in 1978, confirmed by the PCGB in 1979. Herbert Todtmann of Minden-Stemmer made German standard shape Blues a few years later, standardized in 1986.

White Australorp Bantams were made in Germany by Wilhelm Mayland of Wermelskirchen about 1973, with Alan Maskrey following with a British-shape version in the early 1980s. Black and Blue Australorps had followed the Orpington standard in eye, shank and foot colour, but this would have made White Australorps rather too similar to White Sussex for comfort, so White Australorps were made with dark eyes and slate shanks and feet.

Blue Australorp, bantam female. Photo: John Tarren

AUSTRALORP DESCRIPTION

Full details are included in American, British, Dutch, German and New Zealand poultry standards books. Novice breeders should visit shows and established breeders to fully understand the details of size and shape required. Large Australorp weights range from 2.5kg (5½lb) pullets up to 4.5kg (10lb) adult cocks. The bantams have an equivalent weight range of 800 to 1000g (28–36oz), and most appear to be close to these weights.

The comb should be single, straight, not too large and nicely serrated. Eye colour should be very dark brown or black. Comb, lobes, wattles and facial skin should all be red. Many pullets either have red faces and light eyes or dark eyes and equally dark facial skin. Both are faulty, but fortunately most of the dark-faced pullets lighten to red faces in their second year.

Young Black Australorps have black shanks and feet, fading to slate on older birds, the colour required on Blue and White Australorps of all ages. All colours should have white toenails and white foot soles.

Plumage should be pure white on Whites, black with a green gloss on Blacks (blue or purple gloss a serious fault) and bluish-grey with fuzzy lacing on Blues. Blues are by far the most difficult to breed, many being too dark or an uneven mixture of shades.

CHAPTER 5

Barbu d’Anvers (Antwerpse Baardkriel or Antwerp Belgian)

This true bantam is unusual among old poultry breeds in that it has been kept by many more people and in far greater numbers from the 1970s up to the present day than ever before. It was established as a breed to an agreed standard in the late nineteenth century, but what were probably its ancestors existed long before then. Some sources mention that small bearded chickens of the Quail plumage pattern (a characteristic colour variety of Barbu d’Anvers) are depicted in one or more paintings by Albert Cuyp (1620–1691), but no details of exactly which painting(s) are given.

‘Belgian Bantams’. Originally a free gift with Feathered World magazine, 1931. Artist: Harry Hoyle

The history of the breed really started in 1895, when fanciers in bilingual Belgium started showing Barbu d’Anvers/Antwerpse Baardkriel at Brussels (51 birds), Liege and elsewhere. A breed club, Club Avicole du Barbu Nain, was formed in 1904. Nain is French for dwarf, the general term for bantams or miniature chickens in France. There were twenty-three founder members, all still known, the most significant being René Delin (1877–1961, also a specialist poultry artist), Robert Pauwels (who made Barbu d’Grubbe and Barbu d’Everberg, rumpless versions of Barbu d’Anvers and Barbu d’Uccles, fully described in Rare Poultry Breeds), and L. Vander Snickt (a leading Belgian poultry expert at the time). The club published a standard which was officially recognized on 12 May 1905. There were three colour varieties, Black, Cuckoo and White at this stage. The Quail pattern was added on 18 April 1910. Their Club Show on 31 July 1910 had 465 birds entered, representing excellent progress. Het Antwerpse Baardkrielen Club was mentioned in 1916, it not being clear if this was the Flemish name for the Club Avicole du Barbu Nain or if it was a separate name for Flemish speakers.

Belgian fanciers successfully introduced their new bantams to the UK at the Crystal Palace Shows of 1911, 1912 and 1913 in London.Their displays attracted a lot of interest; however, this was mostly from casual visitors and beginners to showing rather than ‘old hands’. Six Black Barbu d’Anvers had been shown by G. de la Kethulle de Ryhore at the 1901 Alexandra Palace Show, London, but not many people seem to have appreciated them. The British Belgian Bantam Club was formed in 1915, the first secretary being Robert Terrot, of Cookham, Berkshire. Mr and Mrs Terrot also promoted Malines fowl, a large Belgian heavy breed. Progress was held back by both world wars and the Great Depression, so Barbu d’Anvers did not really begin to gain popularity until after 1945. Normal life suffered even more in Belgium from 1914 to 1945, so the efforts by Belgian fanciers to popularize their breed in the UK proved vital, as British fanciers were able to help their Belgian friends restock in 1919 and 1945.

Black-Mottled Barbu d’Anvers male. One of the first seen in the UK, exhibited by Mr Jamotte at the 1912 Crystal Palace Show. Artist: A.J. Simpson

Barbu d’Anvers, Black-Mottled male and Cuckoo female. Artist: René Delin, one of the founder breeders. These show the ideal type, which clearly did not exist in 1912

Barbu d’Anvers were held back from achieving greater popularity in the UK before 1945 by the reluctance of many show organizers to provide classes for them, and older judges being less than enthusiastic about this new breed when they had to compete in mixed AOV classes. The British Belgian Bantam Club did not have enough funds, or wealthy members, to guarantee show organizers against losses from the generous prize money offered in those days. Even if there were classes, they were often poorly assessed by unsympathetic judges who seemed to positively refuse to learn about any breed of which they did not approve. Fortunately, now almost all UK shows have several classes of Barbu d’Anvers, which are properly judged. The British Belgian Bantam Club, along with some other True Bantam breed clubs, holds its main annual show in conjunction with the Reading Bantam Club Show, now held at Newbury.

They have been known in the USA since the 1920s, but have not been as popular there as in Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands or (eventually) the UK. Several names for them seem to be used in the USA: Belgian d’Anver, Belgian Bearded d’Anver or Antwerp Belgian. The highest show entry in the USA found by the author was at the 1998 Ohio National Show where 221 were entered by twenty-five exhibitors. Fewer colour varieties are bred in the USA than elsewhere, as seen in this breakdown of the Ohio total: 183 Quail, 20 Self Blue [Lavender?], 11 Black, 5 Blue-Quail, l White and 1 Blue.

BARBU D’ANVERS, TYPE DESCRIPTION

This is a small breed. Exact weights differ in standards books around the world, the clearest weight requirements appearing in Dutch standards: 500g (17oz) pullet, 600g (21oz) hen and cockerel, 700g (25oz) cock. They should be compact and cobby, appearing to have almost no back at all as the profuse neck feathering reaches halfway along the back, and the plumage of the lower back rises to the tail at the same point. The tail is long and held high. On males, the sickle feathers should be fairly straight: more like a sabre than a sickle. Wings are carried pointing down to the ground.

Head characteristics are very important on Barbu d’Anvers, starting with the compact rose comb with a leader (rear spike) following the skull, pointing down the neck. Ideally, wattles should be completely absent as they detract from one of their main features, the well developed beard. This should be in a trilobed formation. Neck hackle feathers should be very profuse, with the breed’s characteristic ‘boule’, some of the feathers on the side of the neck pointing to the rear.

Eye, beak, shank and feet colours vary according to plumage colour variety, all being almost black on Blacks. Many other varieties have red eyes and slate-blue beak, shanks and feet. Cuckoos and Whites have white shanks and feet.

Black Barbu d’Anvers, male. Photo: John Tarren

BARBU D’ANVERS PLUMAGE COLOURS

This breed is best known for the Quail pattern, which exists in five colour versions, detailed below. Millefleur and Porcelaine, colour varieties usually associated with Barbu d’Uccles, are also recognized in Barbu d’Anvers, but are comparatively rare. Other, more conventional, colour varieties of Barbu d’Anvers are Black, Black-Mottle, Blue, Blue-Mottle, Cuckoo, Ermine (as Columbian in other breeds), Fawn-Ermine (as Buff Columbian in other breeds) and Lavender. Self Buff, Black-Red/Partridge and Silver Duckwing (Silver Partridge) are listed as recognized varieties, but rarely seen.

The general colour scheme of Normal Quails consists of light ochre beard, breast and legs contrasting with dark brown (‘umber’) neck, back and tail plumage with bright ochre or golden feather shafts and lacing. Tail feathers on males are glossy greenish-black, again with light shafts and edging. Consult a standards book for full details. Neck, back, wing and tail plumage is not as dark as it should be on many birds. This is because correct, dark ‘top colour’ often brings faulty dark markings on the breast. Breeders, understandably, wish to avoid double mating, but may not achieve the best compromise colours with single mating.

Quail Barbu d’Anvers in Germany and the Netherlands have darker beard, breast and legs than Normal Quails in Belgium and the UK. The shade is a rich buff. These have appeared in the UK, where they are called Red Quail.