3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

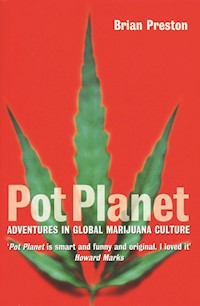

Marijuana is cultivated in nearly every region of the world, from the jungles of Laos to the bedsits of Manchester - and is smoked and enjoyed for medicinal, recreational and spiritual purposes by an estimated 200 million people worldwide. In Pot Planet, Brian Preston set out on a global ganja safari to explore strange new cannabis cultures, to seek out new growers activists and other reefer revolutionaries... and to boldly get baked with each of them. Preston's journeys take him across every stratum of pot cultivation and enjoyment. In Cambodia and Laos he explores the final frontiers of Third World dope tourism. In California, he takes a clear-eyed look at the medicinal marijuana movement, while in Britain, Spain and Switzerland, he finds grudging governments caching up with public tolerance. At the Cannabis cup in Amsterdam he joins the raucous multi-day tasting competition at the international summit of best breeders, growers and connoisseurs in the world. Part investigative travelogue, part cultural history, part manifesto for the unfettered enjoyment of nature's most pleasing herb, Pot Planet is an hilarious odyssey into the multifaceted world of hemp.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

About the Author

Brian Preston is an award-winning journalist whose articles have appeared in Rolling Stone, Details, Playboy, and Vogue. He lives in Vancouver, B.C.

Pot Planet

Adventures in Global Marijuana Culture

Brian Preston

ATLANTIC BOOKS

London

Copyright page

First published in the United States of America in 2002 by Grove Press, Inc.

First published in Great Britain in 2002 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Copyright © Brian Preston 2002

The moral right of Brian Preston to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

The names of certain people in this book have been changed, sometimes at their request. Parts of chapter 10 first appeared in Saturday Night magazine. Part of chapter 11 first appeared in the Vancouver Sun.

9 8 7 6

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 1 84354 084 3

Design by Laura Hammond Hough

Printed in Great Britain by Creative Print and Design (Wales), Ebbw Vale

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Dedication

To everyone who gave me a light

Epigraphs

He had discovered a great law of human action, without knowing it—namely, that in order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to attain.

—Tom Sawyer, by Mark Twain

There! there is happiness; heaven in a teaspoon; happiness, with all its intoxication, all its folly, all its childishness. You can swallow it without fear; it is not fatal … You are now sufficiently provisioned for a long and strange journey; the steamer has whistled, the sails are trimmed; and you have this curious advantage over ordinary travellers, that you have no idea where you are going. You have made your choice; here’s to luck!

—The Poem of Hashish, by Charles Baudelaire

Contents

1: MY HOMETOWN

2: BON VOYAGE

3: NEPAL

4: SOUTHEAST ASIA: THAILAND, LAOS, AND CAMBODIA

5: AUSTRALIA

6: ENGLAND

7: AMSTERDAM

8: SWITZERLAND AND SPAIN

9: MOROCCO

10: THE KOOTENAYS AND THE COAST

11: THE CANNABIS CUP

12: THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

13: TWO JUSTICES

14: POT POLEMIC

EPILOGUE

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

1: MY HOMETOWN

Four years ago Rolling Stone magazine assigned me to write a story about the marijuana culture of Vancouver, British Columbia. Vancouver had been my home for nine years, and although I was a moderate toker by local standards, I had something of a reputation with my stressed New York editor: I was the West Coast stoner dude.

Until then I hadn’t considered myself part of any kind of pot community, any more than someone who picks up a six-pack thinks of himself as part of the beer community. I was a consumer, that’s all, and pot was a product, a form of euphoria that came to me in convenient little plastic Baggies, in eighth or quarter ounces at a time. Sometimes it was good, sometimes it was mediocre, but I smoked it all regardless and never really worried too much about what variety it might be, or who had grown it, or where, or using what methods, any more than I would wonder about the dairy industry when buying a quart of homogenized milk.

Though I’ve smoked it on and off since 1976, I only really started thinking about marijuana seriously when, researching that magazine story, I ended up in a store called the Little Grow Shop in Vancouver. The shop sold hydroponic and other indoor growing supplies, and marijuana seeds over the counter, from the basement of a larger store called Hemp B.C., an upscale head shop selling bongs, books, rolling papers, pipes, hemp jeans, and tie-dyed T-shirts on West Hastings Street. Downstairs in the Little Grow Shop I had the strange feeling of being in some urban mutation of the rural farm supply outlets I’d known as a kid—comfortable places where farmers stood around and swapped talk about the crops. Even the manner of speaking was the same—a clipped, minimalist farmer shorthand. The five staff members had varying experiences growing marijuana outdoors in swampy low-lands, dry prairie, hillsides and valleys; some had grown indoors, in soil or hydroponically, using chemical fertilizers or going totally organic. I learned a lot about growing pot just by eavesdropping at the counter:

“We can’t guarantee which are females. It’s normal to get two or three males in ten seeds.”

“You’re giving them way too much nitrogen.”

“Sativas grow taller than indicas as a rule.”

“You need a light, an exhaust fan, a reservoir to hold your water, soil, pots, nutrients, a good fertilizer, and good seed. For about a five-hundred-dollar start-up you can grow four ounces of pot every two months.”

“Absolutely everybody grows it differently, which tells you it’s real easy to grow.”

Surrounded by super-enlarged photo posters of richly resinous buds from strains like B.C. Kush, White Rhino, and Pearly Girl, the store’s staff dispensed advice, while the owner, Marc Emery, held court from his desk in the back corner of the open room. He wore his hair in a dated, parted-down-the-middle cut that showed too much of a spacious forehead, and had a habit of squinting as if he were trying to keep his glasses from slithering down his nose, yet somehow Emery managed to exude a kind of charisma. Likely you remember someone from high school who was smarter than the teachers and took pleasure in letting them know it. Emery would be the forty-year-old version of that bratty kid.

He toked from a huge fattie consisting of a variety called Shiva Skunk, then lit up a personal favorite, a cross of two varieties, Northern Lights and Blueberry, but smoking huge quantities of reefer didn’t seem to mellow him at all, as pot does most people. He kept up a caustic, funny patter—he doesn’t so much talk as crow—and since he was the boss, no matter how obnoxious or abrasive his opinions became, no one could tell him to shut up.

“American farm boy types come in here often,” he told me, “and they’ll stand there at the book rack, taking in the room over the top of a magazine for the longest time. Then suddenly a big smile comes over their face, and they’ll burst out, ‘Ah cain’t buleeve what ahm seein’ here!’ ”

His desk was a clunky old wooden schoolteacher’s model with three cubic feet of drawers that contained the most intense concentration of marijuana genetics in North America. There were about three hundred little black film canisters in Emery’s desk, each holding seeds of a unique marijuana strain, some back-bred to stability, others a first-generation hybrid. Many of these strains were local varieties that have given Canada’s west coast a reputation for some of the world’s best pot.

He wore a headset to take a constant stream of phone calls, and he was filling some of the $20,000 worth of mail orders he received each and every week, inlaying seeds in cardboard flats that he slid into envelopes bound most often for California and Australia. “Our Commonwealth brothers in Oz are really into pot,” he said. “They’re at the same stage of marijuana acceptance as Canada.”

Listening to the staff chat to customers, I felt humbled, and a little intimidated, to be so thoroughly enlightened: growing pot can be approached with all the dedication and attention to horticultural science that any serious farmer gives his acreage, or any prizewinning gardener her rose bed. Beyond that, the fruits of these labors, the harvested flowers, can be damned or praised with the epicurean subtlety, the gourmandise, that the French or Italians bring to wine and food. Producing and imbibing the best marijuana can be elevated to an art form.

Researching the story gave me an excuse to keep hanging out at the Little Grow Shop. I really did enjoy the no-pretense General Store ambience of the place, plus there was the promise, or I should say the guarantee, of getting totally baked. By chance I met Jorge Cervantes, American author of Indoor Marijuana Horticulture and other outstanding grow books. “This is like a farmer’s co-op,” Jorge said as he took in the scene, “where you can meet growers and ask them what works for them. Europe is still much more advanced than here, but I think Vancouver’s following in the same footsteps as Holland.”

Jorge had come north for a research tour. “As an author, I cannot and will not go to a grow room in the United States,” he said. “I could go to jail for the rest of my life. If a grower gets arrested and they have evidence of me being there, then I’m an accomplice and I’m equally guilty under the RICO statute.” The Racketeering Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act is a federal law from 1970 intended to fight organized crime, on the theory that planning to commit a crime, or even having knowledge of a crime, is the same as committing the crime, and should carry the same punishment. “I’ve been all over the world, and the U.S. is one of those Gestapo countries when it comes to marijuana laws,” Jorge said. “Here in Canada I can visit people who are growing, do it carefully and quietly, and not have any troubles. And it’s nice here.”

Many Americans think of Vancouver as part of the Pacific Northwest, but for Canadians it’s the extreme southwest. In winter it’s as warm as you can get and still be in Canada. It’s like Seattle, only rainier, if you can imagine that. Vancouver’s a great town. One point eight million people, and you can still say, as a friend did lately from a sidewalk chair outside a pleasant café, “Let’s get out of this cultural contrivance and into the beauty of nature.” Nature, in the form of clean beaches, or spectacular temperate rain forest, is twenty minutes away. That makes Vancouver my pick as best city in the world to smoke a doob and go for a walk.

Jorge drove me east to the Vancouver suburb Coquitlam to visit the home of Mike, one of the five growers who at that time made up the Spice of Life seed company. We sat with him in the living room for a while, watching the local hockey team, the Canucks, take on Carolina on the tube.

The house was a labyrinth of white-walled grow rooms, some no bigger than a closet. Jorge happily snapped pictures of me sniffing bud, pictures that Mike was careful to stay out of. Things are cool in Canada, but not that cool. Jorge said, “I can’t believe the attitude in Spain right now. When I take pictures there, the growers want to be in them.”

Mike wished he could be that free. “As far as I’m concerned I’m not doing anything wrong at all,” he said. “It’s a crime that pot’s illegal. It is. How dare they come in here and bust my ass, get the fuck out right now, that’s how I feel about it. Turn around and don’t break any lightbulbs on the way out.”

Jorge said, “You’d make it about a week in the U.S. with that attitude. You’d be kissing the floor with your hands behind your back, a big boot right on your neck”—he made a choking sound—“and every time you’d squeak they’d stomp you a little bit more.”

The plant names were labeled on white plastic knives stuck in the soil: Shishkaberry, Sweet Skunk, Purple Hempstar. The Shishkaberry, like the currently popular Bubbleberry, is a hybrid developed from a strain called Blueberry. Blueberry comes out of various crossings and recrossings of three strains: Highland Thai, also called Juicy Fruit when it was first bred in the 1970s in the American Pacific Northwest; Purple Thai, which was itself a cross between Chocolate Thai and Highland Oaxaca Gold; and a nameless Afghani indica.

This knowledge may sound as though it were difficult to acquire, but truth be told, a ton of information is out there for anyone, for free, on the Internet. This is how Blueberry was described in Marc Emery’s Summer 2000 catalogue: “80% Indica, 20% Sativa. Dates to the late 1970’s. Large producer under optimum conditions. A dense and stout plant with red, purple and blue hues, usually cures to a lavender blue. The finished product has a very fruity aroma and tastes of blueberry. Notable euphoric high of the highest quality, and very long lasting. Medium to large calyxes. Stores well. Height 0.7 to 1 meter. Flowering 45–55 days.”

The genus cannabis belongs to the cannabaceae family, which has only one other member, hops. Indica and sativa are the two major species of the cannabis genus (a third, Ruderalis, native to Russia, is seldom bred for marijuana, although I’ve seen people attempt it indoors in Canada and outdoors in California).

Cannabis sativa originally grew (and still does grow) naturally nearer the equator than indicas. Sativas tend to be tall, from two to six meters, with long thin leaves and loose flowers. They smell fruity. The high is usually described as cerebral and uplifting.

Cannabis indica is associated with the Hindu Kush region, the cooler, mountainous, more northerly terrain of Afghanistan and Pakistan. It’s a smaller plant, one or two meters high, with short, fat leaves and tight, heavily resinous flowers. Almost all commercial strains of cannabis have some indica bred into them, because slow-growing long-limbed pure sativas aren’t profitable. Indicas tend to smell more skunky than sweet. The high is a heavier “body” stone.

Smoke a sativa and go for a swim, and you’re likely to feel yourself to be a water sprite, splashing on the diamond surface. Smoke an indica, and you’ll feel yourself a shark, with an urge to hold long breaths and descend to the murky depths.

Most marijuana varieties have a lineage as complex as Blueberry, but not all of them are as well-documented. The venerable weed is, after all, illegal, and breeding in most places is a clandestine, secretive, risky business. And even if pot were legal, many growers would want to keep trade secrets from their competitors.

Mike pointed to an oddly spindly plant and said, “This one is really interesting, it’s called Parsley Bud. It’s going through a bit of stress right now, but all the leaves grow that way.” Rather than spreading out in the familiar seven-leaf pattern, the crinkly leaves clung in tight bunches. “I’m crossing it with a purple strain to get the color into it, then I’m going to back-cross back, to try and keep some purple color with this leaf structure. It does not look like a pot plant.”

“It looks like it should have berries,” I said.

“The cops could fly over and look for what they’re used to looking for, and not see that one. Great, eh?”

Mike had a new strain called Romulan he wanted us to taste. He was planning on entering it in an upcoming Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam. The Cannabis Cup is a huge smokefest hosted annually by New York-based High Times magazine, America’s leading monthly devoted to marijuana since 1974.

“We should hire someone to dress like a Star Trek character and hand out free samples,” he said. “It’s like any world-class flower show: you’ve gotta impress the judges.”

2: BON VOYAGE

Wild and free for countless millennia, cannabis is believed to have evolved in central Asia. Either that or God created it on the third day, and saw that it was good. When human beings started to figure out how to grow plants, cannabis was one of their first choices. It has been continuously cultivated in China since Neolithic times, about six thousand years ago. In ancient China the plant was used as a cereal grain, for medicinal purposes, and especially for its fibers. The rich wore silk, the poor clothed themselves in sturdy hemp. Hui-Lin Li, a botanist at the University of Pennsylvania, states, “From the standpoint of textile fibers, three centers can be recognized in the ancient Old World—the linen [flax] culture in the Mediterranean region, the cotton culture of India, and the hemp culture in eastern Asia.”

A fifth-century Chinese medical text differentiates between the plant’s “nonpoisonous” seeds (ma-tze) and the “poisonous” fruits (ma-fen), according to Li. The text states, “Ma-fen is not much used in prescriptions (now-a-days). Necromancers use it in combination with ginseng to set forward time in order to reveal future events.” A tenth-century work observes, “It clears blood and cools temperature … it undoes rheumatism. If taken in excess it produces hallucinations and a staggering gait. If taken over the long term, it causes one to communicate with spirits and lightens one’s body.”

From China the plant spread to India, where it was awarded sacred status in the Vedas, the central texts of Hinduism, recorded between 1400 and 1000 B.C. In India’s Ayurvedic medical tradition, cannabis is still prescribed for a variety of ailments. In ancient times the plant spread to all regions except the driest of deserts and the dampest of jungles. It flourished from Norway to South Africa, from England to Japan. It was one of the first plants brought to the New World, by the Spanish to Mexico and South America, the French to Canada, and the British to America.

Mankind’s ancient relationship with cannabis began when some sharp-witted Neolithic Homo sapien thought, Let’s throw some hemp seeds in the soil around the camp here, so we don’t have to walk so far to find them next year. From that long-ago moment, lost in the shroud of undiscovered prehistory, an unbroken human–plant symbiotic continuum flows across the millennia, the centuries, and the years, and, ever-widening like a river delta near the sea, spreads for a moment to include me smoking a joint on a ferry along the west coast of Canada in 2000 A.D.

I’m on my way to be a marijuana judge, at Cannabis Culture magazine’s first-ever Cannabis Culture Cup. Compared with High Times’ Amsterdam Cannabis Cup, this one promises to be pretty modest. In fact, it’s supposed to fit into Marc Emery’s living room, in a rented waterfront house on British Columbia’s mellow Sunshine Coast. Emery is the publisher of Cannabis Culture, which has a circulation of about 60,000.

Twenty-eight months have passed since I first met Marc at his Little Grow Shop. The Vancouver police long ago raided the place, along with the Hemp B.C. store upstairs, and seized inventory worth half a million dollars. Charges have never been laid, and the merchandise has never been returned. Emery promptly reopened, but the city government of Vancouver ultimately shut down Hemp B.C. for good by refusing to renew the store’s business license. Emery then transformed his seed-selling business into a strictly Internet operation, and relocated to the Sunshine Coast.

To get to his house I need to ride from Horseshoe Bay on a big ferry that can carry 360 cars. It’s almost empty on this cool mid-winter day, about 10 Celsius, 50 Fahrenheit. Out of the chilly breeze the sun is warm on my face. Beneath its glinting surface the water looks very cold, black, and secretive. I have a joint to smoke that I’ve cadged from my stoner niece. I love smoking a joint on the ferry, because all that clean water and fresh air seems doubly sharp and bracing when I’m high. The ferry makes it easy to be naturally high on life, of course, but why not just take that natural high and make it even higher?

On the upper deck I wander outdoors in search of a lighter. On the starboard side two rosy-cheeked blond teenage girls sit cross-legged on a big box of life vests, turning their backs to the too-playful sea breeze and trying to ignite some pot in the little bowl of a brass and wood pipe. One of them lowers her chin to tuck her pipe inside her jean jacket and out of the wind. That works.

She lends me the lighter and I perform the same trick, hiding in my coat like a bird tucking beak under wing. We share the smoke of the blessed burning herb, not exactly hiding what we’re doing from the passengers who stroll past us, but pretending we are invisible, as do they. Canada is very civilized that way.

A guy from Nova Scotia with an acoustic guitar invites himself to join us, and we sit on the big life preserver box and sing Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on the Wire” together. The girls’ shy voices are as beautiful as the snow-topped mountains that fall in a skirt of green forest to the distant shore. Under us the vibrating hull shudders along a serpentine path toward a familiar dock. We start talking about ambition: one of the girls is trying to choose between becoming a helicopter pilot or becoming a chiropractor. We decide she can do both if she wants, combine them even: dangle her patients by bungee cords below the chopper, and give their spines a good jerk.

“I feel better, I feel better, just let me down!”

We’re high and happy, all of us. On many occasions marijuana stirs the same impulses in me that make people cry at corny movies. Makes me love the sun, the moon, the earth, and humankind. It’s an alternate state of consciousness that makes life more lovable. How could I not love life when I’m headed to a glorious smokefest? How could I not start bragging? “As a judge I’ll be sampling and rating sixteen varieties of top-flight bud, and our combined overall scores will then determine a champion,” I say matter-of-factly, as if I do this sort of thing every day.

When the ferry docks I see Barge, a Vancouver photographer specializing in shots of marijuana buds, sucking on an eight-inch-long handblown glass pipe and offering tokes to three of his friends, in full view of people in rows of parked cars waiting to drive onto the ferry.

“Doesn’t it make you feel exposed, or vulnerable, to smoke it so openly?” I ask.

He shrugs. “I just act like it’s legal, like it’s perfectly normal.” He offers me a toke, which I take. The other three decline. They’re going to be judges too, and appear to be taking the responsibility seriously. They don’t want to get baked too early. One of them is a twenty-three-year-old marijuana grower named Arthur.

Marc Emery arrives, and we pile into his old International Harvester. Barge scrambles in through the back window with the luggage, Arthur and friends take the backseat, and I get the front passenger seat. I’m being treated like a celebrity.

Marc describes my official judge’s sampling kit: “Some of the people at the lower end of the priority list will be smoking less desirable samples. But you’ve got all flawless buds.”

“Geez, you shouldn’t spoil me.”

“Yes we should, because this has to reflect well in your book.”

He knows I’m writing this book, knows I’m planning to fling myself by the slingshot of velvet-comfort modern air travel to a dozen countries around the world, in order that I might experience the dance of intimacy between humankind and marijuana in all its infinite variety and confusion. In corners of our planet near and far, I want to see how cannabis is cultivated, processed, and ingested, not to mention championed or denigrated. Pot lovers, psychologically landlocked by the War on Drugs, need to be reminded there’s a big ol’ world out there where the DEA doesn’t hold sway. I’m the tour guide for a global gourmet-ganja holiday.

“You’re not going to find better pot anywhere than what you’re going to smoke this weekend,” Marc says. “Every single entry was grown here in B.C., and most of them are B.C. strains. One of them is Arthur’s, as a matter of fact: Mighty Mite/Skunk. There’s Blueberry from Oregon, there’s Shishkaberry, which is old Breeder Steve’s from around here, plus there’s a Texada Time Warp, and a Northern Lights, too. I’ve had them all grown and harvested under exactly the same conditions.”

Marc has been a salesman since the age of eleven. As a boy in London, Ontario, he saved his paper route money to start Marc’s Comics Room, a mail-order comic book business that had 29,000 titles by the time he sold it at sixteen. At age twelve he was buying up vast numbers of bound volumes of American newspapers that a local recycler had bought at auction from the Library of Congress, and cutting out the daily comics to sell to collectors. “I met my first celebrities this way,” he tells me. “Like Mort Walker, who did ‘Beetle Bailey.’ He collected ‘Moon Mullins’ strips from me.” At thirteen he was pulling down four hundred bucks a week tax-free. “One of the motivations for making money was to be able to eat in restaurants. My mom was English and hated to cook and just steamed the hell out of everything. Eating in restaurants was a revelation.”

At sixteen he quit school and started up an antiquarian bookstore. He ran the store for eighteen years, sold it, went to India for two years, then settled in Vancouver in 1994, opened Hemp B.C., and started selling seeds over the counter.

“At that time there were only four or five types of pot around here,” he says. “Big Bud, Hindu Kush—it was all good, but very homogenous, very similar. What we did was buy up a few local strains, and brought in some varieties from Holland. Seeds were almost reinvented in that period, because everyone was just growing from cuttings. The market demanded sensimilla pot, and there weren’t a lot of males around.” Marijuana is one of the few plants (kiwifruit is another) that is either entirely male or entirely female. On most of the world’s plants the female and male sex organs, the pistils and stamens, occur on the same flower.

“We started growing some males, pollinating females, and now there are all these strains,” Marc tells me. “The consumer is demanding name pot now. They want Juicy Fruit, by the Dutch company Sensi Seed Bank, for example, and they’re willing to pay for it. In the U.S. they pay so much for it that the customer is getting sophisticated and demanding it from the dealers.”

Marc Emery Direct Seed Sales is now quite likely the largest seed supplier in the world, with yearly sales of more than a million dollars. “We mail anywhere in the world,” Marc says. “This week alone, we’ve sent seeds to places like Poland, France, and Croatia.”

The sixteen varieties in competition this weekend are all available from Emery on the Internet. “I’ve commissioned this one guy to grow them out for me,” he says. “They’re flushed twenty-one days, so it’ll all burn perfectly.”

“What do you mean ‘flushed’?”

“Flushing is when you just feed the plant water in the latter part of the growing, to get rid of the chemicals from the fertilizers.” Commercial growers don’t bother with niceties like that, he says. “Most growers just do that for five or ten days because they’re anxious to get it to market and pay the rent. Arthur knows all about this.”

In the backseat, Arthur just nods.

“What happens is there tends to be a carbon buildup in the plant material, because of the heavy fertilization,” Marc continues. “One of the ingredients of fertilizers, potassium, is actually like asbestos, a fire retardant, and so when you find pot that doesn’t burn well it’s either wet, which is curable, or it wasn’t flushed long enough, which is not curable. You can always tell if you have perfectly flushed pot if the ashes are white. You want the ash to be powder white when you flick it. If it’s gray or black or anything like that, it ain’t flushed properly.”

After the three-week flushing, the plants in competition were harvested, the buds manicured, which involves clipping off all but the tiniest leaves from around the buds, and then cured for a month. “They sit in my grower’s cedar box, slowly drying out. So these are all flawlessly dried, at their peak potential. You can’t get better. All grown by the same person, with the exception of three strains—so there are no variables. Because some pot could be a great strain genetically, but a bad cure, a bad flush, a bad manicure, or a bad everything can really affect it, you could have the same strain taste completely different and give you a completely different high from grower to grower. All the ones in competition today are in their optimum condition. The only odd thing is, the Afghani seems to be awfully leafy, and I’m not sure why.”

While he’s been talking and driving I’ve been looking at all the tasteful upper-middle-class houses tucked back among big trees, mostly well away from the road. Some of them must have amazing ocean views. “Who lives around here?”

“Mostly people who don’t need to live in the city,” Marc says. “There are a number of potheads, but they’re mostly forty-five to fifty-five years old. I’m hoping the sun comes out, because we live right along the ocean.”

The sun fails to come through; it’s the kind of drizzly misty gray winter day that’s typical here. The Sunshine Coast? A Realtor must have invented that one.

The living room of Marc’s house has a huge fireplace framed by twelve-foot windows with a view of Georgia Strait between the spaced trunks of tall spruce. The judges gather and sit themselves down shoeless on the thick carpet while Marc lays down the rules: “Each of you will be testing sixteen strains, and each of you will have about two ounces total of bud to smoke. That’s about an eighth of an ounce, three grams or so, of each sample for each judge.”

“How much should we smoke of each?” someone asks.

“I would suggest one hit in a pipe, until you get high. Just smoke a small amount and assess it.”

Each of us recieves an obese manila envelope containing sixteen self-sealing numbered Baggies. Mine all contain flawless buds, as promised. Even the little leaves surrounding the buds glisten with resin. Marijuana’s psychoactive ingredient, delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (better known as THC), is found in serious amounts in resin glands that occur most densely on the female flowers—the buds—and on the small leaves that cradle them. Some of the buds Marc’s given me are so gooey with resin, if I threw them at the wall they’d stick.

In the envelope along with the buds there’s a three-page judging form, asking that each strain be rated and commented upon according to six attributes: appearance, fragrance, texture, taste, aftertaste, and stone. The seventh and final category, overall impact, will be used to determine the winners.

We get down to the work of smoking, and the experts start trading opinions:

“I’m going to roll some seven.”

“Seven? I just smoked it. Seven is the red-haired extravaganza with the minty ephemeral kind of fragrance, and I gave it a good score for texture, with a smooth taste.”

“Do you know if eleven is plum bud? It seems like a lemony citrus bud …”

“I’m sure this one is Blueberry. It’s got that unmistakable Blueberry flavor.”

The conversation at times verges close to sounding like pretentious wine-snob chatter. It’s not surprising, really. The wines of the world are made from less than a hundred of the existing five thousand varieties of grape. Marc Emery’s seed company alone offers nearly four hundred marijuana varieties. Variations in taste and aroma in marijuana are potentially as ripe for subtle analysis as are variations in wines. In fact, the aroma wheel developed by A. C. Noble for wine tasting (in which basic olfactory categories, like “fruity,” “floral,” or “pungent,” branch out to more specific scents) has inspired marijuana grower and connoisseur D. J. Short to create a chart for marijuana.

Short’s main cannabis aroma categories are “woody,” “spicy,” “earthen,” “pungent,” “chemical,” and “vegetative.” The more specific flavors branching from these broad phyla can be found in any number of subtle combinations. Obviously the palates (and lungs) of most pot smokers aren’t that subtle, and there’s one major difference between sampling pot and wine: elite wine samplers take a sample taste and spit it out, so that they don’t actually get drunk during the course of testing. Wine experts will discuss aroma, taste, and body till the cows come home, but they don’t often write about the drunk, the inebriation, about the variation of intoxication between, say, a Bordeaux and a Merlot, although I’d argue that a different feeling of tipsiness from a little, and drunkenness from a lot, does make itself felt among different vintages.

Cannabis connoisseurs are less disingenuous about the ultimate appeal of their favorite mood-altering substance than are their wine counterparts. People drink wine to get tipsy or drunk, and people smoke pot to get high. Cannabis connoisseurs inhale and so get high almost immediately. Beyond aroma and taste, they notice differences in the types of highs from one strain to the next, which relate to variations in the sixty or so known cannabinoids found in marijuana, which act upon the main psychoactive element, THC, in ways still little understood.

Three hits is all it takes. Tiny samples from numbers 1, 2, and 3 of my sixteen Baggies. Three good tugs on a pipe, and already I’m too high to tell the effect of one entry from the next. We’re smoking them quickly, one right after another. There are always joints lit and circulating. I take a toke of number 8 and think, Wow, what a fantastic, awesome, head-clearing high, but maybe number 7 from five minutes back is a creeper. Or maybe it’s the combined effect of 1 to 6 amalgamating into a fireball of shivering joy playing hot and cold fingers up my spine. Or maybe I’ve just smoked too much dope to do the job. That does happen. That’s why it’s called a recreational drug. Turning it into a job is ridiculous. The effect of cannabis is to free the mind, not focus it.

Rising from the carpet to the middle of the big circle of cross-legged stoners, Marc Emery teases me about my dilettante’s palate. Nodding toward a woman busily scissoring up some number 6, he says, “You’ll be giving everything eights and nines out of ten, while she’ll be giving things threes and fours.”

He’s right. Everything seems like a nine to me. This is pure organic smoking pleasure. No chemical headache aftereffect. Each toke a gift.

Even a seasoned smoker like Dana Larsen, the editor of Cannabis Culture magazine, admits, “After a joint or two, you’re only really able to judge for taste and flavor, and for how well it burns, as opposed to the effects. Unless it’s really spectacular and cuts through everything else.” He intends to judge the psychoactive qualities of each strain by smoking a different strain each morning for the next two weeks. I decide to do that too. It turns out to be a better way to separate the differing qualities of each high and select favorites.

But my appreciation is inevitably affected by how the world and my responsibilities to it impinge on my day. You could say the difference between good pot and bad is the difference between being in love and having a gastrointestinal disorder, because being in love has moments that feel like a gastrointestinal disorder.

Of my sixteen samples, some buds are covered in clusters of fine red hairs, others wear a shaggy green-blond wig. Some buds are tight and dense, others loose. Some smell like citrus, others skunky, musky, still others like fresh-mown hay. I’m talking smell before lighting. I’m talking sticking your snout in the Baggie to inhale the pungent perfume of the herb. There is a huge variation at that point. And the scents can tantalize. Pot advocates keep telling me cannabis was a major ingredient in nineteenth-century perfumes. I have no trouble believing it.

However, once it’s rolled up and ignited, I find it impossible to rate pot smoke in terms of flavor, as some pot smokers claim to be able to do. Cigars I can tell apart. Good pot from bad I can tell apart. But when all the pot is excellent, as at this intimate coastal competition, it pretty much all smells alike to me.

Barge and I stay overnight at Dana Larsen’s house, and in the morning we eat blueberry pancakes fried in hemp oil. They have a greenish tint but taste delicious. After breakfast Barge is ruthlessly taking the scissors to his samples, pruning every little leaf to reveal nothing but the essential bud. Whoever manicured the buds for the competition has left them way too leafy for his taste. “I’m doing the job someone else should have been doing,” he complains.

Dana sees positives in unmanicured buds. “It’s a good thing, because with all those leaves to protect it, there’ll be fewer trichomes busted off in transport.” When magnified the THC-laden resin glands on the bud look like oily little blobs called trichomes. The most THC-potent of them are called capitate-stalked trichomes, and they look like little gooey mushrooms.

I hesitate to admit it to them, but the way the tiniest leaves wrapped around the bud entered into my appearance ratings yesterday. Some cradled the bud like five perfect little fingers round a softball.

“That’s a personal preference,” says Barge. “I don’t like to see any leaves on it when I smoke it. The calyxes and the hairs and the crystals are far more important when I smoke.” The calyxes and hairs are part of the female flower, and crystal is yet another word for a resin gland. In Holland the terminology gets even weirder, because they call the resin “pollen,” although pollen has nothing to do with it. Cannabis pollen is produced by the male plant, not the female, and the buds we smoke are the females, horny girls denied their pollen and overproducing the sticky resin in the hopes of catching some.

Barge trims off every single leaf and sets them all aside to make butter or cooking oil. “It’s better to make a concentrate form than to smoke all that green leafy matter,” he says. “Anytime you’re smoking, it’s not the best for your lungs.”

He finishes rolling a joint, using the absolute minimum of paper. The joint looks taut as a stuffed sausage skin. He brings it to his lips unlit, and inhales it that way, an act he calls a dry hoot. Dry hoots are the best way to savor the flavor, according to Barge. “Sweet, sappy smell,” he says of this one. He yells to Dana, who is playing with his young daughter in the living room. “Hey, Dana! Number seven. Smells sweet and sappy!”

Marc Emery takes me back to the ferry in his big blue International Harvester. Along the way he stops to buy a massive bouquet of fresh-cut flowers from a roadside stand. It’s the honor system; just a little metal box with a slot for your money. Canada is very civilized that way. We stop for brunch at the Gumboot, a funky restaurant up the coast at Roberts Creek. As he parks, Emery points to the local hemp store next door. “When a community of two thousand people can support one of those, you know you’re in eco-hippie central,” he says.

The Gumboot is packed with dreaded, barefoot, tied-dyed, twenty-something neo-hippies. Emery is wearing a Stranjahs in da night baseball cap, which is about as countercultural as he ever looks. Stranjahs is a semi-underground Vancouver restaurant that cooks with cannabis. Their slogan is “An All You Can Eat Buffet to Make You Hungry.” They use donated shake, not bud. “It cleans you out, plus you get a mild body buzz—great for arthritics,” says founder Cherise Mitchell.

Outside the Gumboot the woman who runs the little juice stand that sells organic drinks of the beet-carrot-ginger type is plugging an upcoming outdoor rave in the woods, proceeds going to save some nearby old-growth rain forest. By her cash register there are postcards hand-lettered with “Gumboot Rules,” a list of mostly too-cute aphorisms like No rain, no rainbows. Emery underlines one with a finger: Goals are deceptive—the unaimed arrow never misses. “This rationalizes a lot of layabout behavior here, though,” he says. “I’ve always been very goal-oriented. Every day needs to have some sense of accomplishment.”

Over brunch we run through the list of places I don’t want to miss on my pot pilgrimage. Nepal, Southeast Asia, Australia, California, Morocco, Spain, France, Switzerland, Holland, and Britain are on the A list. I run out of breath just rhyming them off. My lungs are tender from two days of solid smoking. No stamina.

Marc tells me I cannot leave out Jamaica—no book would be complete. Or India.

“Go to Jaisalmer and find the guy who owns the bhang shop there.”

“Where?”

“Jaisalmer. It’s in the middle of nowhere between Pakistan and India, a wonderful old fortress town built in the fourteenth century in the desert, where nothing deteriorates because it never rains out there,” he says. “You can tell the tourists who’ve been to the bhang shops because they’re the ones taking close-up photos a foot from camels’ faces. There are lots of great places in India. The problem for you is the same as for me—you won’t get approached. If you look straight, no one tries to sell you anything. But look like a dreaded hippie, like these guys”—he surveys the unaimed-arrow crowd at the tables around us—“and they all want to sell you stuff.”

“But is it good pot?”

“Oh yeah. The quality of pot is really good everywhere. I remember in Mysore, India, I hadn’t scored in four weeks, and I’m in the market. A guy looks at me and says, ‘Peter Tosh? Legalize it?’ And I go, ‘Yeah, I like Peter Tosh, and I believe in legalizing it,’ and he goes, ‘Okay, follow me.’ Of course, it’s always going to take a lot longer than they tell you, it’s going to cost a lot more, they’ll say for extra expenses. But you know what? If you give them money in advance in India they will always come back, they will not rip you off! It’s really cool that way.”

“Unlike here at home,” I say, “where every adolescent learns the hard way there’s no legal recourse.”

“Yep. Thailand has good pot, but the paranoia factor is high. The concept of bribery—once you have to start bribing people it gives you an uneasy feeling, it reminds you you’re doing something wrong, and if something doesn’t go right they could just throw you in the brig. If you want to score anywhere in Asia, just find a place where they’re playing Bob Marley music. Malaysia has nothing, it has the death penalty. And pot is like twenty bucks a joint, which is just ridiculous. I remember buying two pounds in Indonesia in 1993 for five hundred dollars. Of course, the paranoia kicks in when you’re wandering around with that much pot in a backpack.”

“I don’t just want to buy and smoke the pot,” I say. “I want to go where they grow it.”

“In Thailand that’s the north, and you’ll have to bribe people for sure,” he says. “That’ll double the paranoia factor. That’ll be a theme of your book, I bet. First of all because it’s something you know about yourself, that you get paranoid easily. And then the sellers are going to magnify the paranoia just because it’s profitable for them.”

I start thinking about something a Vancouver Drug Squad cop told me a few years back: that except for a few timid souls, everyone who wants to smoke pot is doing it already. No one worries about the consequences around here, because it’s a slap on the wrist. But in foreign countries, it’s another matter. I can’t even picture where I might end up, but I can picture myself being Timid as Hell over there. The Timid Toker Abroad.

“You’ll do fine,” Marc says at the ferry dock. “Keep your eyes open, be a little brave, and have a good time.”

3: NEPAL

“Tomorrow is the day of puffing,” Rajiv says. “It is part of our religion. Shiva used to puff hashish, so in the name of Shiva, those who wish to can puff also. Tomorrow everyone is free to puff all through the day, through the night until morning, and the police will not interfere.”

The streets of Kathmandu are crowded with Indian pilgrims who have streamed north from the plains into the mountains of Nepal for the festival—rural people, confused, frightened, and fucking up the traffic flow by not knowing how to get across the roundabout above the temple. Nepali cabdrivers are mellow, usually. This is the only time of year you’ll hear them curse. Fronting the circle across from the police station is the Siva Shakti Fastfood Cafe, and we are eating a lunch of momo, a Tibetan dish of fried meat and vegetable dumplings similar to Japanese gyoza. Rajiv is one of four Nepalese schoolteachers, unmarried guys pushing thirty, who are taking me to the temple at Pashupatinath, on the western edge of the city. They are all nonsmokers of cannabis, but they have befriended me.

Pashupatinath is named for one of Shiva’s incarnations, Pashupati, the Lord or Guardian or Protector of Animals. It is one of the holiest Hindu shrines. Tomorrow night is the culmination of the festival Hindus call Mahashivaratri—Shiva’s Great Night—or more often just Shivaratri, Shiva’s Night.

The Indian scholar Shakti M. Gupta has written that to keep vigil on Shivaratri “is reckoned so meritorious that every orthodox Hindu keeps awake by engaging himself or herself in pious exercises, and Shivaratri in common parlance means a sleepless night … Those who keep vigil on Shivaratri are promised, in the Puranas, material prosperity and paradise after death; the indolent who sleep on this night are destined to lose their worldly goods and go to hell on death.”