Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

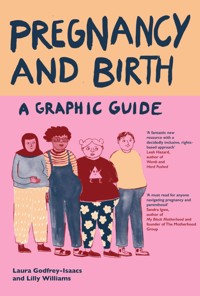

Midwife and award-winning author Laura Godfrey-Isaacs, alongside illustrator Lilly Williams, celebrates the beauty and science of pregnancy and birth. This accessible and approachable book is the perfect guide for expectant parents, as well as anybody interested in knowing more about how we are brought into the world. Covering everything from contractions and fetal positioning to feeding and postnatal care, Pregnancy and Birth: A Graphic Guide emphasises the importance of physical and mental health of mothers and babies while offering a clear and concise insight into the many issues that surround this exciting, but sometimes overwhelming, stage of life.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 122

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Copyright © 2025 Laura Godfrey-Isaacs and Lilly Williams

First published in the UK in 2025 by Icon Books

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978-183773-133-6eBook ISBN: 978-183773-134-3

The right of Laura Godfrey-Isaacs (writer) and Lilly Williams (illustrator) to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988.

The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the Publisher, who also disclaims any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Book design by Becky Bowyer

Appointed GPSR EU Representative: Easy Access System Europe Oü, 16879218 Address: Mustamäe tee 50, 10621, Tallinn, Estonia Contact Details: [email protected], +358 40 500 3575

Icon Books

Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

Contents

1.Introduction to Childbirth and Parenting

2.Pregnancy

3.Birth

4.Feeding Your Baby

5.Post Birth – The Fourth Trimester

6.Looking After Your Baby

7.Resources

8.About the Authors

9.Acknowledgements

Section 1

Introduction to childbirth and parenting

Hello and welcome!

There are lots of ways to make family.

This book is an introductory guide for anyone who is pregnant or thinking about starting a family: cis women, trans and non-binary folk, mothers (whether biological, social or kin), partners and supporters.

You’re embarking on an epic journey, a life-changing experience, and a rite of passage – there will be plenty of bumps along the way, as well as a growing bump!

We will be with you every step of the way, with information, encouragement and support.

We hope to provide you with all the content you need. But, if you have any serious concerns about yourself, your baby or your care throughout the childbirth experience, please speak to your midwife or care providers directly.

We have a reading and resource list at the back of the book where you can find out more on all the topics and issues we talk about.

Welcome to one of the most significant adventures of your life!

Throughout this journey to parenthood you are likely to feel a mixture of emotions!

Your mind will expand (as well as your body) – the brain of a new mother or birth parent makes millions of new connections, and your baby even leaves part of their DNA in your grey matter.

You will be flooded with hormones that help you adapt to being a parent, including oxytocin, the amazing ‘hormone of love’.

We have enormous respect for you wanting to create a new human being, and taking on the job of being a parent – it’s an awesome thing to do!

In this book we use gender inclusive language and diverse images of pregnancy, birth and mothering/parenting in order to welcome everyone and break down any barriers to accessing information and support. Mostly we reference UK maternity services.

Language matters

Some ideas such as ‘informed consent’ (knowing what you are agreeing to in a healthcare context) take on different meanings. An emphasis on the health of the fetus (baby in utero) can sometimes mean that the pregnant person’s wishes are seen as secondary, so it’s important to keep your ‘bodily autonomy’ (control over what happens to you) and your wishes central.

Your body, your choice – and the baby only has legal ‘rights’ once it is born.

Breastfeeding as a term can be used broadly to mean feeding with breastmilk in all its many forms: via your breast, chest or with bottles, finger, tube or with donor milk.

Other terms may be used too, such as maternal milk or human milk.

The politics of pregnancy and birth

It may seem strange to suggest that birth is a political issue, but maternity care is affected by the medical, social and political contexts within which it is located. Awareness of the effects of this has grown recently. Knowing your rights and some of the key principles can assist you as you negotiate your childbirth journey.

Human rights in maternity care are based on the ideas of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UN, 1948) and outline how every healthcare professional must treat you with dignity and respect, consult you about all decisions and support your choices.

Reproductive Justice, developed in the 1990s in the USA, states: it is your right to have a child, not to have a child, and to parent any child in a safe and healthy environment.

The term ‘Obstetric violence’, originally coined by indigenous women in Latin America in the 1990s, identifies how mistreatment or abuse, or the denial of treatment or the choices you want to make during childbirth, is a form of gender-based violence and can be perpetrated by anyone caring for you.

#Metoointhebirthroom sprung from the #Metoo campaign, started by activist Tarana Burke in 2006. This has sought to identify how sexual assault and mistreatment can occur during childbirth, as much as anywhere else.

Decolonising maternity care is a movement that looks at the legacies of healthcare inequality, rooted in colonial beliefs, prejudices and philosophies for Black and Brown people and other minoritised groups.

There are many organisations that support reproductive justice and human rights in childbirth. See our resource list at the back of the book.

Birth and feminism

There are conflicting positions in feminist thinking on birth, mothering and parenting. ‘Biological essentialism’ is an idea propagated since Plato and the ancient Greeks, centred on the idea that there is a natural essence of being a woman that includes mothering and care work.

Essentialism has been challenged by second wave feminists such as Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex (1949) as well as contemporary figures such as Judith Butler who, in Gender Trouble (1990), suggested that gender and therefore ideas of womanhood are socially constructed, or even ‘performed’. They cite the ‘burden’ of reproductive work which historically has kept women in the domestic realm, and subordinate to men.

Later feminist theory has explored the complications and contradictions of mothering and ‘motherhood’ as an institution. An example of this is Adrienne Rich’s Of Woman Born (1976).

Poet Audre Lord, speaking as a Black lesbian, eschews simple binaries and explores the erotic power of reproduction and self-love in works such as Zami: A New Spelling of My Name (1982).

By using an intersectional feminist lens, developed by critical race theorist Kimberlé Crenshaw in the 1980s, we can recognise the multiple factors which influence our experiences, and may make us subject to additional risk or disadvantage, including in birth and mothering/care work, such as gender, sexuality, ethnicity, physical abilities and socio-economic status.

Whatever your position, there are many views and multiple perspectives.

Midwives and ‘wise women’

Midwives are the main caregivers during pregnancy, birth and early parenthood in the UK and many European countries. The spread of the profession is patchy – the UN estimates we are short of 900,000 midwives globally (State of the World’s Midwifery, 2021).

Historically birth took place at home, with midwives or ‘wise women’ attending. Knowledge of physiology, herbs and traditional remedies were passed down the generations. Commonly a posse of ‘gossips’ (female relatives and friends from the community) would help by getting the birth room ready, providing support through labour, and making special food and drink.

Midwives had the power to baptise and give the last rites, though they were often blamed for stillbirths and thought to be in league with the devil. In the Middle Ages, many were accused of witchcraft.

Under increasing scrutiny the Church and medical profession sought to control them and midwives started to be licensed. In 1550 midwives in England took an oath to serve ‘God and the Poor’. Even though women were historically denied entry to medical training, some of the earliest books on childbirth were written by midwives, such as The Midwives Book of 1671 by Jane Sharp, and in the 18th century Angelique-Marguerite du Coudray designed sophisticated stitched anatomical teaching aids.

Regulatory bodies today such as the UK Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) still expect individuals to be of good character, and declare themselves ‘fit to practise’.

The medicalisation of birth

From the 16th century onwards male-midwives, the precursor to the modern obstetrician (meaning ‘one who stands opposite’), entered the birth room. Surgeons, such as William Smellie from Scotland, introduced instruments like forceps. Many developments in obstetrics were driven by unethical experiments made on enslaved, poor and powerless women by figures like the American James Marion Sims in the 17th century.

Today, there is a paradox between overuse of interventions in high income countries, which can lead to unnecessary procedures and an interruption to the physiology of birth, and the issue of medical support often being given too late in lower income countries. This can inevitably cause harm. Western birthing techniques are often introduced into healthcare systems ignoring the specific socioeconomic and cultural context.

as discussed by Professor of Midwifery Studies Soo Downe, from the Lancet paper by Suellen Miller (2016).

Statistics from 2021, for caesarean birth rates around the world, show a huge disparity between the lowest, at 5% in sub-Saharan Africa, to the highest, 43% in Latin America. The World Health Organisation recommends a level of 10–15%.

Instrumental births (e.g. using forceps) and induction-of-labour rates are also continuing to rise in many maternity services, with only minimal reductions in maternal mortality or stillbirths. Rates of maternal mortality in the USA, where there is a high incidence of medicalisation, is increasing, particularly for Black and other minoritised women.

What’s a ‘normal’ or natural birth?

Birth is an important life event that encompasses powerful physical, psychological and cultural factors. People’s views on the subject can be complex and emotive.

The medicalisation of birth is a process that has undoubtedly sought to make it safer, but has also led to an increase in the monitoring, control and management of the birthing body. In response there have been moves to understand and support the ‘normal’ physiological process of birth and, for some, ‘reclaim’ it from a medical paradigm.

Advocating for birth to be seen primarily as a ‘normal’ process and as a social, cultural and spiritual event has led to strategies to increase home birth, reduce interventions and support the physiology of birth.

However, not everyone wants a home birth. Some people want to have a caesarean and many are happy giving birth in a medical environment, where they feel most safe.

Using the word ‘normal’ or ‘natural’ to describe a birth that has occurred without interventions, such as instruments, medications, anaesthetic or surgery, has led to some people, who did not have this type of experience, feel that they have failed and their birth was ‘abnormal’.

In the research project Re:Birth, led by the Royal College of Midwives (UK) in 2022, the language women and people wanted around their births was discussed, and it was clear that this should be individualised and empowering. They found the majority of people want a positive and safe birth experience, whatever the mode or outcome.

Birth inequalities for Black, Brown and minoritised people

For Black, Brown and other minoritised birthing people in Western maternity services, there continue to be unacceptable disparities in outcomes. Higher mortality rates, levels of stillbirth, neonatal deaths and lower rates of breastfeeding are recorded.

Some medical conditions present differently on Black or Brown skin compared to white skin, leading to lower detection rates or misdiagnosis, which points to historical bias and gaps in medical education.

High profile figures such as American tennis star Serena Williams, who suffered a near fatal blot clot after a caesarean birth, have spoken out and highlighted the racism and bias that has contributed to these disparities in birth outcomes.

Much advocacy work is being done to address the issues, from campaigning organisations, such as Five X More (for the Black community) and Shifrah UK (for the Jewish community), to movements to decolonise healthcare and healthcare education, as well as political calls to action.

Positive images of Black motherhood by influencers such as Chaneen Saliee (UK) provide important ways to celebrate experiences of parenting and are powerful ways to increase representation and visibility.

If you have concerns about your care, and need advocacy, further guidance and support, speak to a trusted caregiver and the organisations we recommend in our resource list.

Gender inclusion in perinatal care

If you are from the LGBTQ+ community and starting a family there are some disparities in birth outcomes and feeding, particularly for trans and non-binary birthing people.

Films and accounts of people’s experiences of birth and parenting can also help by providing visibility which normalises queer families, such as A Deal with the Universe by filmmaker and birth parent Jason Barker (2018) and Seahorse (2019), directed by Jeanie Finlay about trans dad Freddy McConnell.

LGBTQ+ peer-support groups can provide community and solidarity, and there are many on social media, as well as organisations such as the LGBT Foundation who can provide guidance and support.

Fertility and assisted conception

Research shows around 1 in 7 heterosexual couples in the UK will have fertility issues – difficulty conceiving and taking a pregnancy to term. Many others will seek assisted conception using ART (Assisted Reproductive Technology) due to social or medical reasons, using a variety of means such as IVF (in vitro fertilisation), donated eggs or surrogacy.

Equality and access to this treatment should not be withheld. For example there shouldn’t be barriers to LGBTQ+ families, single women, birthing people, or disabled people accessing care.

If you have used assisted conception, it’s often a long journey with serious financial, physical and psychological impacts that can include multiple pregnancy losses. Organisations such as UK Fertility Fest (UK) are important in providing a space to discuss issues of infertility, and support can be found via groups online.

Birth in the media

In previous generations we might have seen our mothers, sisters or neighbours give birth at home. Historically, depictions in the arts and media were rare, and in the UK a birth was not seen on TV untill the 1950s.

The infamous photo of pregnant Demi Moore by Annie Leibovitz, seen on the cover of Vanity Fair magazine in 1991, heralded an explosion of interest. There has since been a proliferation of reality dramas such as One Born Every Minute, a growing preoccupation on social media and a near obsession over celebrity pregnancies.