99,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

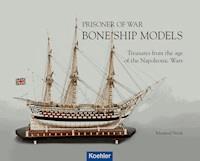

During 1792-1815, the period of the Coalition Wars and the Napoleonic Wars between France and Europe, prisoners were taken on both sides. The majority of them were confined, sometimes for many years, in England and Scotland. Some of the prisoners built ship models from scraps of wood or mutton and beef bones. Rigging was made of silk or whatever other fine material could be obtained. The prisoners developed an art form and the models were sold to the public through the guards. This trade enabled the prisoner to acquire ivory and special tools to make the models all the more decorative. The remain highly sought after and valuable collectors' items to this day. This book shows the beauty of the models selected as the finest in the Peter Tamm Collection in the International Maritime Museum of Hamburg.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 146

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Manfred Stein

PRISONER OF WAR BONE SHIP MODELS

Treasures from the age of the Napoleonic Wars

Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft · Hamburg

Jacket photos: Michaela Hegenbarth

We will gladly send a complete list of available titles.

Please send an e-mail with your address to: vertrieb@koehler-books.de

Visit us on the internet: www.koehler-books.de

Bibliographical information of the German National Library

The German National Library registers this publication in the German National Bibliography; detailed bibliographical data can be called up on the internet: http://dnb.d-nb.de.

ISBN 978-3-7822-1205-2

eISBN 978-3-7822-1461-2

Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg

© 2015 by Maximilian Verlag, Hamburg

A company of Tamm Media

All rights reserved

Assistance with translation: Christopher Watson

Layout und production: Inge Mellenthin

Content

Acknowledgements

List of maps and illustrations

Introduction

The period of the Coalition Wars and Napoleonic Wars 1792–1815

The British-American War 1812–1815

The origin of prisoner of war bone ship models

Who built the models, and how?

The fleet of model bone ships in the International Maritime Museum, Hamburg (IMMH)

Showcase “b”, First rate warship

Showcase “c”, British Frigate

Showcase “c”, French Corvette

Showcase “c”, ETNA, French Topsail schooner

Showcase “c”, British Navy Cutter

Showcase “c”, HMS AJAX, Third rate warship

Showcase “c”, HMS DIDON, French Frigate

Showcase “f”, LA COURAGEUSE, British Frigate

Showcase “g”, First rate warship

Showcase “j”, HMS GLORY ex LA GLOIRE

Showcase “m”, LA SYRENE, British Frigate

Showcase “n”, CHESAPEAKE, US Frigate

Epilogue

Index

Bibliography

Footnotes

Appendix I

Appendix II

Appendix III

Author

For Lilo

Acknowledgements

My thanks go to Gerrit Menzel and Philip von Klösterlein on the staff of the International Maritime Museum Hamburg (IMMH) and the photographer Michaela Hegenbarth of Altona Museum Hamburg for their untiring support during the making of the photos for this publication. They assisted in numerous photo sessions over several months. I am also indebted to other staff members of the IMMH not mentioned here for their help during the production process of the manuscript.

And, last but not least, I should like to thank Prof. Peter Tamm, who over decades collected prisoner of war bone ship models built during the period of the Napoleonic Wars. This passion led to a collection that is unique worldwide and by far the largest exhibited in a museum. This book project is based on his initiative.

List of maps and illustrations

Maps

Fig. 1: Location of hulks (△), strong houses (○) and farms (□), © Manfred Stein

Fig. 2: Location of prisons; circles: model centres, © Manfred Stein

Fig. 3: Location of parole towns, © Manfred Stein

Illustrations

Fig. 4: Presentation of prisoners of war in a hulk building a model bone ship (International Maritime Museum, Hamburg), © Manfred Stein

Fig. 5: Hulks, as portrayed by Abell, © Abell, Francis, 1914

Fig. 6: Location of the orlop deck (coloured in red) on a hulk,© Chambers, 1728

Fig. 7: Orlop deck of the hulk BRUNSWICK, Chatham; 460 prisoners were cooped up on an area of 39 m x 12 m with 1.50 m headroom, © Abell, Francis, 1914

Fig. 8: Dartmoor prisoner of war camp; the massacre on April 6th 1815, © Waterhouse, Benjamin, 1816

Fig. 9: Prison market in Norman Cross; painting by Arthur Claude Cooke, 1909, © Walker, T. J., 1913

Fig. 10: “Archimedes drill” (left) made by the author himself and a piece of pork bone; the little hole was made with this drill, © Manfred Stein

Fig. 11: A primitive bow lathe, made by the author, for turning a piece of wood by swaying the bow, © Manfred Stein

Fig. 12: Bone parts for a model bone ship, bleached by the author and turned (from left: capstan, muzzle, small capstan), © Manfred Stein

Fig. 13: Automation model (mechanical toy) made from bone, “Spinning Lady“, original in the German Technical Museum, Berlin, © Manfred Stein

Fig. 14: Wooden box, covered with bone carvings, original in the German Technical Museum, Berlin, © Manfred Stein

Fig. 15: Configuration of showcases with model bone ships on deck 8 of IMMH (b–n); at “a” prisoners of war are shown at work in a hulk (Fig. 4), © Manfred Stein

Fig. 16: English transom of a 74 Frigate; gunports in the counter on both sides of the rudder post (H), © Falconer, William, 1780

Fig. 17: French transom of HMS DIDON (French Frigate), ➤showcase “c”,© Michaela Hegenbarth

Fig. 18: British Frigate, gunports in the counter, pull cord, © Michaela Hegenbarth

Fig. 19: Mechanics of the gun retraction, © Manfred Stein

Fig. C5_29a: Ajax the Lesser molesting Cassandra in the Temple of Pallas Athene, public domain

Fig. C5_36a: Tirailleur, French marine, © Manfred Stein

Fig. M7a: Old French crest, La Syrène, public domain

Fig. N12a: carronade, public domain

All other photos from Fig. B1 on page 28, to Fig. N34 on page 321, and the photos on page 26, 322, 346 are © Michaela Hegenbarth

Introduction

The collection of prisoner of war bone ship models in the International Maritime Museum, Hamburg comprises 31 vessels. This is not a great deal, one might argue, but compared with collections in other museums in the world it is a very impressive fleet and worldwide the largest collection of bone ships exhibited in a museum. At present (2014), there are more than 400 bone ships that can be verified.1 Most (169) of these are located in British museums. German museums and collectors account for 53 of these marvels of the times around 1800. They include the German Technical Museum Berlin (5), German Shipping Museum, Bremerhaven (1), Lower Weser Maritime Museum, Brake (1) and Foundation of Historical Museums Hamburg (Altona Museum and Museum of Hamburg History) (6), private collectors (6), the German Museum, Munich (1) and the Germanic Museum, Nuremberg (1).

What is so special about these ship models? Is it the material they are made of: cattle bones and human hair, but also ivory, tortoise shell and baleen? Is it the mysteriousness of the environment where the ship models were built? Gloomy hulks on which hundreds of prisoners were herded together in cramped conditions, or large camps for prisoners of war, specially built for 7,000 or more internees? Or is it the feeling of seeing something rare and extraordinary?

In the preface to the catalogue2 of the exhibition of the Altona Museum “Ships made of bone and ivory”, which presented several bone ships from September 22nd to November 21st 1976, Gerhard Wietek emphasised the fascination these ship models have on the beholder: “The museum has several of these ship models made of bone and ivory, which owing to the unusual material and sophisticated workmanship exert a strong fascination” and “Most of these models built at the height of classicism around 1800, assigning the white of the classicist figures to the ship hull, are in England…” When looking at the bone ship models, we inevitably wonder: how did the prisoners of war manage to ensure that the planks, stern galleries and masts, made from cattle bone, are so white today – even after more than two hundred years? How did they build the rigging? They used their own hair or other organic material, as we now know from the literature.3

Many questions can be asked. Are there answers? Among ship modelers there are some specialists who have dedicated themselves to the restoration of these marvellous artifacts. They have added much to our knowledge about these special ship models. An outstanding expert was Ewart Freeston4, a ship modeller from New Zealand and the authority for ship models built by prisoners of war between 1775 and 1825. And we must not forget to mention the great collector and bone ship expert, the late Clive L. Lloyd.5 We know how Lloyd started his collecting passion: “one day when he strolled along Portobello Road Market in London, he purchased a small, nicely carved “Ivory ship“. Later he found out that it was not made from ivory, but from cattle bone and was built by a French prisoner of war. This chance find was the first step in a long journey during which he learned much about bone ships and other work crafted by prisoners of war, which he could add to his large collection (including 22 model bone ships). In his publication, Lloyd presents in Volume I the arts and crafts of prisoners of war. His books cover the period between 1756 and 1816, an age of wars. Lloyd presents in his collection the arts and crafts of the prisoners of war of that period beginning with the Seven Years’ War between USA and Great Britain and followed by the Wars of the Coalitions, the Napoleonic Wars and finally the conflicts between the USA and Great Britain between 1812 and 1815. In Volume II, we learn about the types of English prisons during those 60 violent years: the inhumane detention on the hulks, unrigged warships or merchant vessels anchored in English ports, the depots, prisoner of war camps such as Norman Cross near Peterborough, or Dartmoor, in the vicinity of Plymouth, intended for up to 8,000 prisoners of war, and confinement on parole, lodging in private houses, which was only for officers. Some exhibits from Clive Lloyd’s collection, including a bone ship model (see below, Inv. No. M-463), found their way into the collection of Peter Tamm. Peter Tamm told me about how he came to collect model bone ships when we discussed this book project in September 2012. When he was a young journalist working for the newspaper Hamburger Abendblatt, Peter Tamm visited the Onassis yacht CHRISTINA when she was docked in a shipyard in Hamburg for an inspection. Onassis took Peter Tamm on a tour of the vessel. He noticed white model ships in display cabinets on the walls of the ship’s stairway and asked Onassis about their origin. Onassis explained that they had been made by prisoners of war held by the British during the Napoleonic Wars. This marked the beginning of Peter Tamm’s passion for collecting prisoner of war bone ship models, which led to a bone ship collection that is the largest in the world accessible to the public.

The time of the Wars of the Coalitions and the Napoleonic Wars (1792–1815) will be considered below with the focus on the form of detention in Britain. This will be followed by a chapter on the origin of the model bone ships and who built them and the further art work created by the prisoners of war. The main chapter will present the highlights of the bone ship fleet of the International Maritime Museum Hamburg. Some models are presented in detail in this chapter. The main idea behind the presentation of the individual bone ship models is to analyse the elements deriving from the style of the time, classicism. In contrast to the pertinent literature, which considers the models from the aspect of historic exact modeling,6 this book aims to show the beauty of the individual models and evoke a feeling of how “human destinies in combination with manual skill and popular composition speak a touching language in these model ships which address heart and mind.“7

At the end of this book a selection of literature is given to suggest further reading on bone ships at the time of the Napoleonic Wars. That the subject of bone ships appeals even today is shown by the novel by Fee-Christine Aks published in 2012. In this work, the reader is taken on a tour starting with the daily routine of a museum in northern Germany. The reader learns about the dark secret of a bone ship model connected with the age of the Napoleonic Wars and participates in an exciting historic criminal case.

A list of details of the bone ship models of the Peter Tamm collection is given in Annex I. This is followed by a table displaying the photos of each of the 31 bone ship models of the collection (Annex II), and by photos and dates of bone ship models (Appendix III, worldwide). The bone ship models described in Annex I are considered in another publication of the author.8

The period of the Coalition Wars and Napoleonic Wars 1792–1815

France’s declaration of war on Austria and Prussia ushered in an era of wars on the European continent. During the course of hostilities on land and at sea, tens of thousands of people lost their lives or were mutilated and hundreds of thousands of prisoners of war were confined, sometimes for many years, in England and Scotland. It is estimated that about 200,000 prisoners of war were held in Great Britain between 1793 and 1815. After only a brief respite following the peace of Amiens (1802), hostilities with Napoleon began in 1803 and lasted until his abdication eleven years later. In this period, 122,400 prisoners of war of many nations were held in the British prison system, including 72,000 in 1814.9,10 From 1799, the administration of prisoners of war was under the Transport Office (Transport Board) of the British Admiralty.11 The prisoners of war thus bore the letters TO (Transport Office) on the front and back of their saffran yellow prison clothes.

Fig. 1 Location of hulks (△), strong houses (○) and farms (□)

The prisoners of war were confined in prisons distributed over England and Scotland, in hulks (dismantled warships or merchant vessels), which were anchored in harbours along the English southern coast and near London (Fig. 1), and prisons, concentrated in the south of England (Fig. 2), but also located near the North Sea coast, such as Yarmouth and Tynemouth, near Manchester and Liverpool and in Scotland Edinburgh and Perth.12

Fig. 2 Location of prisons; circles: model centres (see Table 1)

Other detention centres were large farms, borough gaols and so-called strong houses (Fig. 1). Officers (midshipmen and higher ranks) were accommodated in private houses “on parole”. They played a special role in the social life of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland during the 60 years of wars.13 Between 1803 and 1813, there were 50 parole towns (Fig. 3). The officers had to sign a contract that regulated how far they could move in the vicinity of the parole town and when they had to return to their quarters in the evening.

Table 1Locations with prison camps14

DoverBristolLeekChathamTauntonChesterfieldTonbridgeStapletonLancaster CastleLewes CastlePlymouthManchesterLewes Naval PrisonDartmoorLiverpoolWinchesterMilbayPrestonPortsmouthPenrynTynemouthPortchester CastleFalmouthSelkirkForton (Gosport)YarmouthEdinburghHilsea (Portsmouth)Norman CrossValleyfieldDorchesterShrewsburyPerthIn February 1796, the problem of accommodating the prisoners of war became increasingly urgent. The British Admiralty was concerned about the prospect of large numbers of prisoners coming into Britain. The capacity of existing prisons on land was depleted and the provision of hulks did not keep up with the demand. In December 1796, construction of the first prisoner of war camp in Britain began at Norman Cross, near Peterborough. At that time, Britain had no experience with prison camps of this size. It was planned to accommodate up to 7,000 prisoners of war. The facility was built from prefabricated wooden parts, transported from London.

Table 2Parole towns between 1803 and 181315

AbergavennyHawickOdihamAlresfordJedburghOkehamptonAndoverKelsoOswestryAshbourneLanarkPeeblesAshburtonLauderPeterboroughAshby-de-la-ZouchLauncestonReadingBiggarLeekSanquharBishop’s CastleLichfieldSelkirkBishop’s WalthamLlanfyllinSouth MoltonBreconLochmabenTavistockBridgnorthLockerbieThameChesterfieldMelroseTivertonChippenhamMontgomeryWantageCreditonMoreton-HampsteadWelshpoolCuparNewtown (Powys)WhitchurchDumfriesNorthamptonWincantonHambledonNorth TawtonFig. 3 Location of parole towns (see Table 2)

Fig. 4 Presentation of prisoners of war in a hulk building a model bone ship (International Maritime Museum, Hamburg)

Instead of terming these detention centres prisoner of war camps, the Transport Office chose the trivializing designation depot. The first prisoners of war came to Norman Cross as early as March 1797. The building of Dartmoor, the infamous granite prison in the moor, known from detective stories, began in 1805. The first prisoners of war came to Dartmoor in May 1809.16 In 1811, the famous British naval hero, Lord Thomas Cochrane, “paid a visit to Dartmoor where 6,000 prisoners were incarcerated in shocking conditions. On his return to London he stood up in the House of Commons and drew the attention of the members to the state of the prison where he had observed men queuing for hours in the pouring rain to receive inedible food. ‘Consequently one thousand were soaked through in the morning attending for their breakfast, and one thousand more at dinner. Thus a third were constantly wet, many without a shift of clothes.’17The overcrowding of prisoners at Dartmoor was largely caused by Napoleon’s refusal to exchange prisoners of war.… but with the nation at war against a formidable enemy most of the members were indifferent to the sufferings of the thousands of French prisoners confined in rotten hulks in Portsmouth harbour or in bleak prison buildings on distant moors.”18 In 1814, there were nine large prisoner of war camps: in Dartmoor, Norman Cross, Millbay, Stapleton, Valleyfield, Forton, Portchester, Chatham and Perth,