14,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Fernhurst Books Limited

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

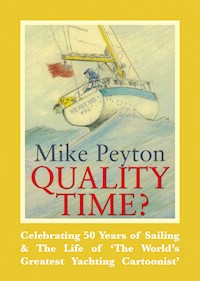

Published to celebrate the life of Mike Peyton, 'the world's greatest yachting cartoonist', this second edition features personal tributes from some 12 other successful and well-known sailors (including Sir Robin Knox-Johnston, Sir Ben Ainslie and Tom Cunliffe). They all recognise Mike's observational talent and comment on how sailors see themselves (or their friends) in his cartoons. Along with 80 of his incomparable cartoons, Mike Peyton recounts how he became a yachting cartoonist and his fifty years of sailing. So as well as chuckling at the cartoons themselves there is the opportunity to learn from Peyton's 50 years of experience of sailing different boats, meeting a variety of sailors, and getting into – and out of – some truly hilarious situations.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

To celebrate the life of Mike Peyton

This second edition published in 2017 by Fernhurst Books Limited 62 Brandon Parade, Holly Walk, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, CV32 4JE, UK Tel: +44 (0) 1926 337488 | www.fernhurstbooks.com

Copyright © 2005 Mike Peyton

The first edition published in 2005 by Fernhurst Books

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a license issued by The Copyright Licensing Agency Ltd, Saffron House, 6-10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS, UK, without the permission in writing of the Publisher.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The Publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Paperback ISBN 978-1-912177-01-1 eBook - EPub: 978-1-912621-12-5 Mobi: 978-1-912621-13-2

The publisher would like to thank Kath Peyton for her kind support of the publication of this second edition. Our thoughts go out to her and her family. We would also like to thank our authors who have contributed their personal tributes to Mike. Cartoons first published in Practical Boat Owner and Yachting Monthly magazines Artwork and first edition cover design by Veronica Gates Edited by Simon Davison

Dedication

Contents

1. Fifty Years of Sailing

2. Deep Water

3. Land in Sight

4. All Ashore

5. Jumbles

6. Below Decks

7. Stopped for the Moment

‘Tea up skip.’

1

Fifty years of Sailing

When you work as a freelance and your publisher says write a few words on how you became a yachting cartoonist, you write. So here we go.

I drew my first cartoon, and others, for a wall newspaper in a German prison camp. I went over the wire shortly afterwards and had no time to continue this line of work when I joined up with the Russian army, but that cartoon was a portent for the future. With the war won, a grateful government was giving grants for further education if you were able to prove interrupted training owing to the past hostilities. As all Adolf Hitler has interrupted in my case was two evening classes on drawing a week, I applied for a grant with little hope of success. But fate, or I think it was, was on my side. During the war I had served in the Western Desert in what the press of the day called the Desert Rats, but which we knew as the ‘effing Mickey Mouse Club’. My particular unit was the recce battalion of the 50th Northumbrian Division where I entered the battalion’s efforts on the situation map, us in red and them in black.

Probably the first cartoon I drew

As I also carried the map, where the C.O. went I went too, like Mary’s little lamb. As he was very enthusiastic I sometimes thought he pushed our luck a bit too far. However, I survived but he didn’t. Sometimes in those distant days we went to what were called ‘conferences’ where a few officers met in the vastness of the desert and conferred, and one of these officers, with a photographic memory I assume, was on the board of examiners who saw me to decide if I might be a suitable candidate for Manchester Art School. Whether his recognising me swung the day I have no idea, however we did exchange a few words about these momentous times during a coffee break, so I doubt if it did me any harm. And so I became an Art Student and was taught how to draw.

The yachting bit took a bit longer.

After a year at Manchester I transferred to a London Art School - which was fine except that my grant was based on my living at home. If as an art student I did not actually starve in a garret, I was often pretty hungry on the third floor up. I scrubbed out pubs etc. to earn the wherewithal to live and pay for my digs and I often hitched home were the food was free. It was these trips home and the conversations with lorry drivers that gave me the ideas for cartoons for magazines such as Commercial Motor. And it was also at this stage I drifted imperceptibly into sailing.

England was on its uppers in those post-war days and many people were selling up and leaving the country. I met a man in a pub in Richmond who was emigrating and I bought a canvas canoe off him. It was about twelve foot long, with a twelve-foot mast and leeboards. The upper reaches of the Thames soon palled and gradually I worked my way downstream. At night I generally slept on moored lighters and I remember once frying breakfast on the primus, overlooked by Big Ben. Eventually I arrived in salt water and learned to reef and found out about tides the hard way.

Then there is a big gap in this learning curve, as I got married to Kath my long-suffering wife. Many years later I was sailing down the Thames on a Thames barge and I pointed out to the skipper the saltings opposite the Chapman light and I told him I had spent the first night of my honeymoon there. His reply was, “You must be effing joking!” Obviously he was very unimaginative and couldn’t visualise the full moon and huge fire of driftwood in the shelter of the seawall. However, that was the last trip we had in the canoe as we were on our way to walk in the Alps, and we followed the usual procedure of handing it over to someone to look after and use until we returned. In this case to the Tonbridge Sea Scouts. We never returned to Tonbridge so, who knows, it may still be there?

After a few yeas of work, and travelling in Europe when we had the money, we thought that before we settled down we would have one last fling and decided on a trip working our way across Canada and back across the States. One of the best interludes on this journey was a canoe expedition into the bush in Northern Ontario. Planning for this I visualised all the tins of food we would need and, even worse, all the dollars we would need to buy them and thought there must be a better way. Then came the thought, what did the old time trappers do? They had no supermarkets and Toronto library had the answer. The old trappers lived off what they termed the three “B’s”: bacon, beans and bannock (a primitive bread made of flour and water). The only decision to be made was the size of the side of bacon and the size of the sacks of flour and beans. I mention all this because years later when I was running a charter boat I tried to get my charterers to accept the balanced nutritious diet bit but they demurred. With hindsight I realised the only way one could work up an appetite for this basic food was to spend a full day paddling a canoe with the odd break of a couple of miles portage of a seventy pound craft.

Back in England we drew a circle around London, where I knew my work would be. The circle had a fifty mile radius and we went house hunting wherever the line crossed a river. Subconsciously something was working. With impeccable timing Kath was left £800 and with that behind us we found and bought a derelict cottage. It had no floors or unbroken windows, but for £750 what could one expect? But we ignored the drawbacks: it was only a few minutes walk from a tidal creek in the upper reaches of the River Crouch. Though I did not realise it at the time, we had arrived.

It was the creek and its boats in their mud berths and their owners that immediately attracted me. The boats, like their owners, were a motley collection: an old smack whose buyer recouped the price he had paid for her in the eels he found in the mud inside her bilges; a barge yacht whose owner told the tale of racing a mattress down the river to Burnham but was beaten because the mattress got a better slant in Cliff Reach; a lifeboat conversion bought for a song because its owner hadn’t come back from the war. There was even a live-aboard on an old bridging pontoon. They were as a whole a subspecies of the yachting world emerging from primeval mud. They bought their yachting gear from the outlets with the self-explanatory name of Army Surplus Stores. When I bought my first boat and with the previous owner sailed it back to the creek, I fitted in like an oar in a rowlock. I would come over the sea wall in the winter and look to see which boat had a smoking chimney - for they had solid fuel stoves - and that’s where I would go for the first cup of tea of the day.

Obviously the only thing that stopped this crew having proper yachts was a shortage of money. But they were all getting around that in their own way for they all had a boat of some description. The lifeboat conversion was a case in point. Britain then had a huge Merchant Navy and all their ships carried lifeboats which, in accordance with Board of Trade regulation, had to be renewed after a certain period of time – so the end result was obvious. There were about three standard sizes of them and they had a ready market. In fact there was a popular book of the time titled Lifeboat into Yacht and you would often see the end results of people who had read this book out sailing, and realise how the various owners had interpreted it.