Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Heliotrope Books

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

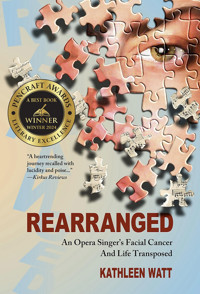

Kirkus Reviews Best Indie Books of the Year (2023) PenCraft Book Award for Best Nonfiction (Winter 2024) In lyrical prose, with musical allusions, clinical references, and a bit of comic relief, Rearranged follows Kathleen Watt's plunge from the operatic stage into the netherworld of hospital life through the devastation of cancer, and out the other side. Kathleen was a New York opera singer at mid-career, with a steady, lucrative chorus job at the Metropolitan Opera and solo gigs elsewhere, anticipating her best year ever. Instead, a vicious bone cancer blew her plans to smithereens, along with her face. Bit by bit, through a brutal alchemy of toxins, titanium screws, and infinite kindness, she discovered new arrangements for old pieces, in a life catastrophically transposed. Not only a heart-wrenching medical odyssey, but an ultimately joyous personal journey of transformation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 517

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Advance Praise for Rearranged

“Watt is a sharply descriptive writer who is unafraid to address the horror of her treatment … Unapologetically frank, the author also has a wry, sometimes self-effacing sense of humor that brings levity to a distressing subject. … The result is a finely textured and courageous literary memoir that is inspirational and, at times, darkly amusing.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A gripping portrayal of the devastation cancer can spread in one’s health, relationships, and dreams, and Watt’s sweeping storytelling will transport readers to each procedure and hospital room alongside her. She provides insights into the medical torment involved with her treatment, such as being comatose and experiencing ICU psychosis, and ultimately gifts readers with front row seats to her most triumphant performance to date—surviving cancer and having the strength and courage to relive the harrowing journey within the pages of this story. The end result is both heart-breaking and uplifting and will touch the heart of any readers affected by a life-altering illness.”

—Publisher’s Weekly

“Kathleen Watt’s narrative memoir reveals her indomitable humanity, indefatigable spirit, and remarkable endurance. She has written with transparency, bravery, honesty, and fairness. The rhythm, cadence and artistry of her words embodies her forever-musicianship, and she has deployed her gifted voice in a tour-de-force written performance. Patients, health care professionals and every-day folk alike will benefit greatly from her lessons imparted and her wisdom shared.”

—Douglas Brandoff, MD, FAAHPM, Attending Physician, Palliative Care Clinic, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute; Assistant Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Alumnus, Juilliard Pre-College Division, cello

“Kathleen Watt has turned her harrowing experience as an opera singer diagnosed with facial bone cancer into a story that is fresh, captivating, and also remarkably entertaining. Her voice—smart, funny, and disarmingly forthright—makes this book shine. I find myself in awe of her sheer bravado and resilience in overcoming all odds to share her story and hard-won wisdom with all of us.”

—Helen Fremont, award-winning author of national bestsellers After Long SilenceandThe Escape Artist

“Watt’s account of her experience with Osteogenic Sarcoma … is a very intimate portrayal ... Anyone going through something like this will absolutely benefit from reading this beautifully written book.”

—Peter D. Costantino, MD, FACS, Brain and Spine Surgery of New York

“Rearranged is a ... memoir of a heart-wrenching battle with a rare facial cancer that derailed Watt’s singing career and her life. Her astonishing honesty in recounting the details of her journey was sometimes horrifying, often humorous, but always truly inspirational.”

—Lori Laitman, acclaimed composer of operas, choral works, and art songs

“Funny, profoundly moving and leaves the reader gasping at the … treatments and setbacks Kathleen endures … [A] must-read for anybody interested in the fortitude and generosity of the human spirit, in how our identities adapt to illness—and for all doctors and professional caregivers.”

—Mark Gilbert, PhD, Portrait Artist, Professor of Medical Humanities; University of Nebraska, Omaha

“Watt perfectly captures the exhilaration and madcap excitement of life backstage at the Metropolitan Opera, where she was a member of the Extra Chorus. Her writing about the singer’s life is so vivid and personal that when she discovers [she has] aggressive facial cancer, it hits the reader hard. I’m bowled over by Watt’s bravery in having lived to tell this harrowing tale, and for sharing it all so candidly.”

—Amy Burton, leading lyric soprano at major opera companies and in recital and cabaret around the globe

“Kathleen Watt’s courage, energy, curiosity, and sheer engagement with life have carried her through challenges that would be unimaginable—except that her clear, lively prose and precise, fearless medical descriptions make it impossible NOT to imagine her experiences. Candid, unsentimental, and vivid, Rearranged is an inspiring book on multiple levels.”

—Rachel Hadas, Rutgers University classics professor and award-winning author of more than twenty books of poetry, essays, and translations

“I am writing in praise of Rearranged to testify that a facial-cancer memoir by an opera singer can be a Gesamtkunstwerk. Kathleen Watt takes the reader through her vivid, painstaking, occasionally self-mocking, excruciating, ecstatic journey… [as] an author who pushes through…to emerge with resolutions intact; and ever-grateful for her passion, so do we.”

—Neil Baldwin, author of Martha Graham: When Dance Became Modern

“What does it mean to be de-faced: to have your neck, throat, nose, eye sockets, eyelids, cheeks, tongue, and teeth disfigured? A harrowing account of the toll taken by treatments of osteogenic sarcoma—told by a woman who brings the same grit to the ordeal that she exhibited in becoming a chorister in the Metropolitan Opera Company.”

—Susan Gubar, Professor Emerita at Indiana University, author of Debulked, and “Living with Cancer” series for The New York Times online

“Kathleen Watt has written a brave and honest memoir about her battle with facial cancer, [which] upended her career as an opera singer and her marriage, and required adapting to life with a permanent disfigurement. [A] fierce examination of our culture’s…obsession with female beauty and the perils of our convoluted healthcare system… [Y]ou’ll also find moments of surprising lightness and humor, and a willingness to stay open to the possibility of a new version of joy.”

—Julie Metz, author of The New York Times bestselling memoir Perfection, and Eva and Eve

“In Kathleen Watt’s world of protracted illness and recovery, body-wrenching chemotherapy is seen as character-building, and humor as life-saving medicine...[Rearranged is] about what illness changes, but even more so, what remains.”

—Sara Arnell, author of There Will Be Lobster: Memoir of a Midlife Crisis

“Clear-eyed curiosity and indefatigable engagement propel Watt’s memoir... Courage, loyalty, medical expertise, and determination seal the cracks of a well-examined life…[A] story told with grace, honesty, and the humor necessary to survive becoming, as expressed by Montaigne, ‘one of those monsters’.”

—Don Cummings, author of Bent But Not Broken: A Memoir

“The unforgettable, often funny, sometimes catastrophic, story of a life rearranged by more than thirty surgeries ... With the odds repeatedly stacked against Watt, Rearranged affirms that warriors and heroes still walk amongst us.”

—Glenn Alpert, Former Metropolitan Opera Tenor, Life Coach

“A rare facial bone cancer derails Kathleen Watt’s life as an opera singer, but with an indomitable spirit, Watt fights back, enduring some thirty surgeries and countless rounds of chemotherapy. Watt uncovers a deep well of compassion and support from her family and friends, propelling her forward … despite “whatever storms may howl.”

—Faith Wilcox, award-winning author of Hope Is a Bright Star: A Mother’s Memoir of Love, Loss, and Learning to Live Again (She Writes Press, 2021)

“...Kathleen has subverted the well-worn tropes of medical memoir, instead writing a story that trills with candour and authenticity. The writing itself is lyrically evocative, affecting and profoundly moving, while the story is one of true grit…Rearranged is a story of hope … a worthy and much needed addition to the canon of medical memoir … Rearranged is set to become a seminal memoir on not just what it is to have cancer and survive, but what it means to be human.”

—Carly-Jay Metcalfe, author of Breath, forthcoming March 2024 from University of Queensland Press

Copyright © 2023 Kathleen Watt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by an information storage or retrieval system now known or hereafter invented—except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review to be printed in a magazine or newspaper—without permission in writing from the publisher.

Heliotrope Books LLC

ISBN 978-1-956474 34-3

ISBN 978-1-956474 35-0 eBook

Cover by Kathleen WattInterior photos courtesy of Kathleen Watt

Typeset by Heliotrope Books

Oh for a cinnamon scone

Contents

Foreword by Cori Ellison

Book I – Diagnosis

Chapter 1. The Bump

Chapter 2. Dentists I

Chapter 3. Dentists II

Chapter 4. Dentists I Redux

Chapter 5. Then What?

Book II – Prepped and Draped

Chapter 6. Head Shots

Chapter 7. Meeting the Big C

Chapter 8. Doctors I

Chapter 9. Doctors II, or Caveat Emptor

Chapter 10. Like the Gonzalez Boy

Chapter 11. Dancing Day I

Chapter 12. Tidings from All Over

Book III – Hospital Time

Chapter 13. Monday

Chapter 14. Family Waiting Room

Chapter 15. Surgery I

Chapter 16. Surgery II

Chapter 17. Friday

Chapter 18. The Two-Handed Yankauer

Chapter 19. Trach Life

Chapter 20. Déjà Vu

Chapter 21. Helping Them Help Me

Chapter 22. First Do No Harm

Chapter 23. Room 203

Chapter 24. Angles of Repose

Chapter 25. Ahoy from the Bed

Chapter 26. Thirst

Chapter 27. Prepped, Draped, and Accompanied

Chapter 28. What Can I Get You (How am I Doing)?

Chapter 29. Life on the Cot

Book IV – Unexpected Visitors

Chapter 30. Reality Bites

Chapter 31. The Wedding Suite

Chapter 32. The Piers

Chapter 33. Football and Trash

Chapter 34. Super Mario Brothers in My Pump

Chapter 35. Man from Psych

Chapter 36. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari

Chapter 37. Fashion Shoot

Book V – Homecoming

Chapter 38. Dip and Switch

Chapter 39. Gracious Living

Chapter 40. Packing

Chapter 41. Sashay

Chapter 42. Scribblings

Chapter 43. New Life Skills

Chapter 44. Going Home

Chapter 45. Generous Margins

Chapter 46. Definitive Obturation

Chapter 47. Dancing Day II

Chapter 48. Sound Bites

Book VI – A Wing, A Prayer, and A Portacath

Chapter 49. Talking to the Man

Chapter 50. Taking a Measurement

Chapter 51. Protocols | Consequences

Chapter 52. Ifosfamide, Or Baldy Upstairs

Chapter 53. Adriamycin: Here’s Looking at You, Kid

Chapter 54. Jane, Or My Hat is Full

Chapter 55. Pirate

Chapter 56. Way Cool in the Key Food

Chapter 57. AGMA

Chapter 58. Victoriana

Book VII – Hospital Time, Overheard

Chapter 59. Honey, I’m a Monster

Chapter 60. In the Waiting Room

Chapter 61. The Fabric

Book VIII – Cancer Free Hospital Rat

Chapter 62. Willy Nilly

Chapter 63. A Way Forward

Chapter 64. Gilda’s and the VFW

Chapter 65. Scripted Miniseries

Chapter 66. The Rule of Three

Chapter 67. The Brazilian Way

Chapter 68. Teeth By Night

Chapter 69. Good Humor at Home and Abroad

Chapter 70. Saws, Bores, and Needle-Nose Pliers

Chapter 71. Inch by Inch

Chapter 72. Another Flap in the Face

Chapter 73. On the Town

Book IX – Surgery to Infinity

Chapter 74. The Wound That Wouldn’t Heal

Chapter 75. Shareholders

Chapter 76. September Monstrosity

Chapter 77. Sequestered Shard, Or The Surgeon’s Workbench

Chapter 78. Roxy

Chapter 79. Ars longa, vita brevis

Chapter 80. Adjuncts

Chapter 81. Circling the Drain

Book X – Enough to Go Around

Chapter 82. View From the Pew

Chapter 83. Worlds Colliding

Chapter 84. Back to Work

Chapter 85. The Drain

Chapter 86. Rich Soil

Epilogue

Afterword

Acknowledgments

Sources

Resources

Foreword

More decades ago than I like to admit, fresh out of music school, I had the crazy good fortune to land smack dab on the very stage that had obsessed me since the age of seven: the Metropolitan Opera. My entrance wasn’t the grand one of which all singers dream; rather, I tiptoed on as a member of the Met’s Extra Chorus, a lucky band of freelancers hired for industrial-strength shows like Turandot, Aida, Parsifal, Boris Godunov, and Peter Grimes, beefing up the company’s already huge regiment of “lifers”, the Regular Chorus, a larger-than-life family of talents who might themselves have been famous soloists if not for fill-in-the-blank.

If I wasn’t, like my childhood idols, striding downstage center to let fly a glorious solo high B-flat (Cut me a break. I’m a mezzo.), I was at least sharing that massive stage with some of them, seeing the same thrilling, terrifying vista, and most importantly, observing their astonishing artistry up close and personal. It was the world’s best opera school.

A few seasons into my Met tenure, the fun element increased exponentially when a new soprano joined our ranks: the elegant, effortlessly stylish, curiously intriguing Kathleen Watt. Different as we were (and are), we bonded durably through our commonalities: the slightly snooty intellectualism, the quick and somewhat subversive wit, the 1990s version of out-and-proud, and colloquies so absorbing that an upcoming musical cue felt like a rude intrusion. I’m not proud of it, but once we even missed an offstage choral entrance.

Inevitably our friendship extended beyond the Met Stage Door. There were cheap, exotic dinners with Kathleen and her then-partner, visits to their Brooklyn home with my amazing dachshund companion Puckie in tow (much to the chagrin of their two cats), picnics and boat rides with Puckie and the lasses in Central Park. There was their unforgettably joyous wedding in a Hudson Valley winery. And, oh yes, there was once an inordinately fancy birthday dinner for me which was followed by the most epic hangover I’ve ever experienced.

Back at the Met, on one ostensibly ordinary day, as we contemplated the comparative edibility of the cafeteria’s offerings, Kathleen casually mentioned an oral irregularity that her dentist was exploring. Not long after, our merry world imploded. I’ll let Kathleen tell you the rest of that story, because she’s better at it, and it’s hers to tell.

I’m writing this foreword, though, because I was there, witnessing from a fairly safe and helpless distance, trying to ride that tidal wave with her in whatever small way I could. And eventually trying to shepherd her manifold gifts toward some new modes of expression. That wasn’t always easy; we had our ups and downs, as friends sometimes do. And Kathleen’s life and mine have since diverged in many ways, have indeed become almost converses. I continued my operatic career, she her pursuit of domestic stability and strong family ties. I’ve remained a staunch City Mouse, while she has become a keen Country Mouse. Yet we’ve always managed to reconnect, picking up as if no time or distance has intervened. These days, it’s mostly over sporadic Zooms and periodic urban sushi dinners. And now I have the honor of introducing you to this treasured friend who has become a formidable writer, and her remarkable book.

Unfolding against a deftly drawn backdrop of 1990s New York City, Rearranged, Kathleen Watt’s gripping memoir, is much more than an account of her long, winding struggle with, and steep eventual victory over a deadly disease. It is also an honest glimpse at the life of an aspiring opera singer and its august pinnacle, the storied Metropolitan Opera—a world exotic to most, but instantly recognizable and perfectly normal to anyone who has lived in it, like the back of a piece of scenery (“…twenty-some-odd feet of plastered plywood, buttressed by two-by-fours, secured with sandbags and sub-contracted stagehands standing by with Phillips-head drill-bits,” as she puts it).

Not long after making us comfy in her world, Kathleen abruptly conjures the split seconds during which all normalcy was shattered by a terrifying, out-of-left-field cancer diagnosis first delivered via an ordinary, everyday 1990s telephone answering machine. From there, we hurtle along with her into an uncharted sea of bewildering new medical minutiae, discomfiting hospital life, and impossible choices for which nobody is prepared.

That absorbing main narrative is seamlessly interwoven with essential backstories and side stories of her remarkable New England family, quietly heroic medical professionals, and a fiercely stalwart life partner, who help to propel her toward her new normal, disfigured but triumphantly reconfigured, and healthy.

This unforgettable memoir is eloquently written, keenly observed, and intellectually imposing. Yet it reads with the swift pace, dramatic clarity, and enthralling suspense of a page-turner novel. By turns, it may make you think deeply, laugh out loud, tear up, or even flinch. But you cannot look away.

—Cori Ellison, New York City, 2023

Kathleen Watt: The last head shot

Kathleen Watt as Carmen

Book I

Diagnosis

You don’t really know you’re ill until

the doctor tells you so [and]

the knowledge that you are ill is one of the

momentous experiences

of your life.

—Anatole Broyard

Intoxicated by My Illness, and Other Writings on Life

Chapter 1 • The Bump

“What a glorious day!” I cried, just as my mother had, all my life, any day the sun shone, whether breezy and balmy, boiling-hot, or bone-chillingly cold, as it was that January day in 1997. I was ditching my daily practice to drive upstate with my partner Evie, for a mid-week ski holiday on her thirty-fifth birthday. Sportswomen we were not. But we liked the outfits, we liked the weather, and we liked each other—a lot.

Evie and I had been fundamentally coupled ten years by then, and I knew her indomitable spirit. It was as easy to overlook as it was impossible to miss, once you knew her. Slight and quiet, she presented a gamine figure in a crowd, open-faced, soft-spoken, wide eyes bright. “Who would believe that little peanut is a lawyer,” cooed my father. But Evie was a canny native New Yorker, disarmingly self-assured, with a profound appreciation of life’s dark comedy, which regularly expressed itself in a clap of irrepressible laughter that I loved.

We hit the slopes at an unpretentious resort behind the Shawangunks—she a fearless beginner, I a rusty novice—our form shaky, our gear kinda goofy, and all of it unabashedly fun. Après-ski, après dinner and cognac, after the glowing fire in the hearth, but before the spa, the jammies, and the rest, I thought of sharing my secret.

Keeping secrets? We don’t keep secrets. Do we?

“Evie, give me your finger,” I said, shoving it into my mouth. “Feel that? You feel anything? What do you think that is?”

“Hmm. Yeah, that bump in the gum there? Does it hurt? No? Okay, good. You better ask the dentist when you see him next month.”

Aha! It wasn’t my imagination. There was, in fact, a bump, in the gumline at the back of my upper jaw. My mind eased just to have my suspicion corroborated, and by the one person who would cheerfully finger my molars on demand. We drifted blithely through the rest of the evening and woke to another shimmering winter’s day. We carved out a few more pretty good turns, packed our rental for an early drive back, and pulled into Brooklyn with just enough time to regroup for the Met’s Cavalleria Rusticana.

*

The subway station-stop serving the New York Metropolitan Opera at Lincoln Center is called, helpfully, “Lincoln Center Station”, and gives directly onto the wide corridors beneath Lincoln Center Plaza, which lead eventually to the Met’s underground maze of rehearsal halls and practice rooms. This goes a long way to allay the aggravation of a commute from Brooklyn, always subject to the vicissitudes of New York’s antiquated transit system. En route to Lincoln Center, at least you can know that when you get there, you’re there.

Consequently, I usually cut my timing recklessly close. My arrival too often became an indecorous sprint from the station platform, down a flight of stairs on the uptown side of Broadway, crossing the Great White Way through the tunnel beneath, and up another flight on the downtown side, two steps at a time. In long strides down the corridor, dodging sightseers and theatergoers, I passed the Lincoln Center Parking Garage, and the loading dock where costumed animal handlers receive the day’s co-starring livestock, then through an unglamorous double door to the Met’s signature interior of garnet-red. In the outer lobby, a few vaguely familiar stage-parents attended to gifted offspring. I paused at the chorus sign-in sheet, one photo-copied page clipped to a music stand, where a No. 2 pencil dangled by a string, totally old-school. Finally I waved my laminated picture-ID toward a friendly uniformed guard who buzzed me through the traffic-scuffed swinging half-door.

That Saturday I was in for a quick and easy matinée with Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana (Rustic Chivalry). This popular one-act is an archetype of the verismo genre, featuring naturalistic realism, where coarse country folk burst onto the stage with boisterous laughter, lusty jealousies, blood and guts. Verismo opera gives to ordinary human drama the same high-art treatment once reserved for the rarified demigods and royalty of earlier styles.

Impassioned, sometimes rough singing supplants the flawless vocalism of the bel canto ideal, and all other production values likewise collude toward verisimilitude. Sand is strewn among the cobblestones, awnings, and fish stalls of a Sicilian-style cathedral square. Shovel-wielding vendors follow a clattering buckboard drawn by a pair of live burros. Peasants mingle, merchants haggle, voices of an Easter choir ascend from within the soaring cathedral.

Most of this is stage-magic, of course. The buckboard is real enough, and the burros (thus, the shovels). But these “uncouth villagers” are NYC opera singers, sophisticated and style-savvy. The wine flasks are authentic, but they dispense a soft beverage of principals’ choice—anything other than wine (insurance issues). The cathedral belfry rises high out of sight, twenty-some-odd feet of plastered plywood, buttressed by two-by-fours, secured with sandbags and sub-contracted stagehands standing by with Phillips-head drill-bits. Fan-blasted incense and backstage voices complete the illusion of a vast sacred interior where a choir rehearses for Easter Mass.

My three years in the so-called Extra Chorus taught me to appreciate these off-stage assignments, for they make up in expediency (no costume, no makeup, no waiting around) for what they lack in glory—and pay the same scale as a six-hour Parsifal. I could sign in and pop over to my place among the two-by-fours under the main stage without even stopping by my cubby in the Chorus Women’s Dressing Room. This afternoon, I’d be able to drop in, sing my bit, hop a train, and be home for supper.

Were this an evening performance, mind you, I would have driven my car into Manhattan from Brooklyn, just because of the return. For each night, beneath the city that never sleeps, after theaters have drawn the final curtain, before the clubs’ last call, the subway system assumes its most erratic idiosyncrasies. And late nights under NYC are less perilous than non-New Yorkers might imagine. For one thing, there’s safety in the sheer numbers of homeward bound theatergoers, shift-workers, and clubbers who crowd station platforms into the night. But the crowds thin as the tracks fan toward the outer boroughs. Trains become fewer and farther between, and protocols lag. At one outlying stop, three or four transit cops might step from each of three or four middle cars, falling into step on the platform, doors agape behind them, delaying us for some mysterious minutes, until returning with the last of a pizza slice in hand. Our ride resumes. Time slows. Ridership dwindles. On the station platform where I transfer to the Brooklyn line, I’m often waiting alone.

A windowless armored car of mustardy yellow known as the Money Train lumbers from station to station, on an ever-changing nightly schedule (until the modern MetroCard eventually forces its retirement), lingering at each for armed guards to collect a padlocked canvas cash bag from each token booth. This would be the unluckiest timing. Stuck behind the Money Train, the remaining riders of a late-night Brooklyn-bound train would drag home later than ever.

So, for evening performances, I would drive. Inbound I would encounter foreseeable bottlenecks at Brooklyn Bridge and on the FDR South, looping around the toe and up the west side of Manhattan. Plus, I’d have to calculate extra time for the shark-like prowl around a block or two for parking on the curb (either that or spring for the pricey Lincoln Center Garage). But West Street would be free of its worst weekday tangles. And after the performance, my drive back along the pitch-black Hudson River would unfurl for miles ahead, a broad, empty expressway festooned in long strings of green traffic lights, spared the surging sea of rush-hour headlights and braking taillights. A silky asphalt straight-shot home to bed.

*

“The only reason to do that job is for the money,” said my principal coach and main champion.

As a New York solo singer, my coaches and some colleagues heartily discouraged me from auditioning for the Metropolitan Opera Chorus. For despite its many splendors, the impetus of choral singing is the obverse of solo singing. Solo singing, to a principal soloist, is a solemn calling, a vocation of service to song, a delicious labor of love. The “labor” is the hard work of accounting for both a physical gift and a creative troth—a distinctly individual mantle, and the dogged dedication to magnify it. A dedication that sooner or later, in careers large and small, gives way to an inevitable reckoning, usually preceded by a period of disillusionment, or concession, and always of soul-searching. Unlike in a “singing job”, where singers en masse ply their vocal mechanics uniformly, under direction, for remuneration. A job like (forgive me) the Metropolitan Opera Chorus.

Or so I had come to believe.

Personally, I hadn’t even considered the money—only the imprimatur of singing at the Met—until my mentor said it out loud. Standing before him, I strained to dim the dollar signs I knew flashed in my eyes.

It would be niceto be able to pay the bills on time, for once.

So one brilliant April afternoon, I slipped into the queue of overdressed hopefuls winding through the Met’s underground warren, and out onto the sun-splashed plaza of Lincoln Center. My ambivalence about accepting the job, were it to be offered, liberated me into confidence and cheeky insouciance. When my turn on the stage came, I led with “In questa reggia”, Turandot’s big aria, a showpiece so virtuosic it risks provoking the audition gods. I routinely opened with this stentorian aria anyway, less for effect than for the way it centered my voice, especially when adrenalin was running wild (in extremis, one needs a strategy). And on that day, even my high C rang out with authority.

❧❧❧

Chapter 2 • Dentists I

Evie’s January birthday always arrived as a welcome remedy to the post-holiday blahs. In 1997, we returned from our getaway to our cozy Brooklyn brownstone, refreshed for the winter ahead. We took up our regular round of subways to and from our city jobs, with the occasional dip into grand opera, warming in a glow of busy domestic tranquility.

Next up on my calendar would be that dentist appointment. I’d have my annual cleaning and get the scoop on the innocuous bump. I looked forward to the date, though it would cost me a gig-day’s wage.

The dentist’s office in Hadley, Massachusetts, was a long drive from Brooklyn, but—though my siblings had long since flown, my mother was more than six sad years gone, and my father already a year in the ground—I had yet to replace the family dentist.

Twelve miles and ninety minutes north of New York City, the RFK Memorial Bridge (née Triborough) offers the first opportunity to exhale. Pulling out of Yonkers traffic, I left behind the clutter of shoreline industry which had once all but killed the Hudson. I liked to imagine the river as the Rhein and picture the cliffs of the Palisades as framed by Bierstadt and Gifford and the other painters of the Hudson River School—almost all European émigrés—and try to encounter afresh this American Eden.

I made my way north through a sloppy wintry mix to the I-91 exit that for so long had led me to my parents’ house on Cherry Lane, but now, eerily, took me only to the dentist. Passing familiar road signs—Soda & Pet Food City, Northampton Tubs—I realized I looked forward to seeing Dr. S., although I’d never known him well. In the graveled lot where chickens once ranged all over an old New England farmstead, I turned off the motor and let my bones rattle to a stop along with the car. The characteristic veranda of this farmhouse-turned-dental-office seemed to make even a visit to the dentist feel like going home.

In the rearview mirror, I refreshed my lip-liner and took another moment to fluff, hoping to suggest, in the unforgiving glare of the examining light, I had at least made an effort. Unfolding my legs, I stepped into the frozen slush of midwinter with the self-assurance of a just-checked face. I climbed the farmhouse treads, crossed the porch, and let myself into a magazine-strewn country parlor.

A row of hydraulic examining chairs faced enormous windows overlooking broad fields of fallow rows running out to a tall hedge on the horizon. Patients faced a sweep of sky as they waited to recline and open wide. How often I’d felt my heart rate slow before that framed expanse, sometimes an infinite flat blue, or busy with scudding cumulonimbus puffs, sometimes heavy and low with tomorrow’s snow, as on this February day. I had relocated to New York years earlier, and two hundred miles across three states was a long way to go for a cleaning. But where else would I find a comparable view from the chair?

Not far into the exam, my dentist saw something to quiet the office chatter. Ah! The bump. The thing Evie had scoped out for me after skiing, consulting in the offhand way any couple might, leading to this overdue appointment. Somewhat irregularly, my dentist then and there sent me for a further consult.

Across the field from the farmhouse was a modern dental suite with low walls of red brick and frosted glass. How smooth of my dentist, I reflected, to consult with a trusted colleague before going one step further. As my dentist called ahead, I returned through the slush to my car for the short hop to the endodontist around the corner.

Ho! What good sense! How prescient of me to have maintained ties to civilityand grace, physicians who cooperate in efficient, expert care, in bucolic fields of Massachusetts under snow-laden skies. Not only was I unreasonably self-satisfied, but also, I was certain these collegial dentists would figure out the problem and fix me right up.

Inside the more clinical but no less convivial offices across the field, the staff had seen me coming and straightaway led me to an examining chair. Once seated, I learned the endodontist had an urgent commitment that afternoon and would not be able to see the job through, but because my dentist had pressed him, he would take a look. The bump, the thing I had laughed about with Evie, which had given pause to my family dentist, now seemed to be troubling his pal, the endodontist.

“Yes. I see it now,” he said. “And you say you feel no pain? Honestly, you know, you should consider finding a local dentist. That would be my recommendation to you, because, you know, this is going to take some time.”

“Time? No problem, Doctor! My time is all flex.”

“But perhaps several visits…A root canal, a recovery period, fittings…Unforeseeable consequences…Difficult to manage from afar…Now, unfortunately, I must go.”

And then he was gone. I took his advice and drove back to Brooklyn to look for a local dentist to manage my root canal.

❧❧❧

Chapter 3 • Dentists II

Back in New York—back in my days of perfect health and careless health care—I was a multi-gigging freelancer with catastrophic coverage at best, and no dental at all. My options were limited: call 1-800-DENTIST—or call the equally anonymous friend-of-Evie’s-boss’s-boyfriend’s-dentist.

Evie’s boss was the long-time editor of a ubiquitous Legal Index, one lagging way behind the digital revolution already overtaking publishing. Evie was exactly where she needed to be, and a generous benefits package made it worthwhile—which package did not yet include domestic partners. So I chose the six-degrees-of-separation, hoping for a financial break on my anticipated crowns.

My mistake.

From Evie’s boss’s dog-eared Post-it® I read the endodontist’s address to my cab driver, feeling sullen as we drove into the mid-morning shadows of Lexington Avenue south of Grand Central. I knew this neighborhood from my first months in Manhattan, freelancing in 1983 in a layout-and-paste-up bullpen with three graying graphics guys, letting their Lucky Strikes ash while reminiscing about the glue-pot days and Frankiefrom Hoboken.

A too-small elevator in peeling gunmetal-grey brought me to a low floor on the airshaft side of the building. I walked into an office that seemed both obsolete and popped-up. The open door barely cleared the receptionist’s half-wall, and an indoor-outdoor carpet of uncertain hue buckled at the corner. I would have reconsidered, had I not been greeted immediately by someone who knew someone who knew me and had been expecting me. I took my position under the halogen lamp. I did not see the dentist enter.

“You know. . .” said she, a so-far uncredentialed total stranger, “I think they have the wrong tooth here.” She exuded a whiff of the freelancer herself. “I see this bump over here.” She pressed on my gum. “That doesn’t hurt?”

“No,” I garbled around her gloved fingers.

“Okay, does this? Does that?” More dental prodding I barely felt. “Well, that’s because it’s not that tooth,” she concluded. “So, we’ll do the root canal on this one. Okay?”

The view…Well. The room had no view. Unless you count the airshaft, which was not unusual in Manhattan. There were grimy baseboards in one direction and broken acoustic tiles in the other. Again, not uncommon. Without much consolation, I satisfied myself the sterile instruments gleamed. Various other strangers wandered in and out of the tiny exam room, mostly behind the chair and out of my sight. I thought I caught a glimpse of Evie’s boss’ boyfriend. In word and inflection, what I overheard sounded to me like supervisory scrutiny, as though she were being monitored in her performance, perhaps resuming a practice after an undefined hiatus…Or perhaps my imagination. With a mouth-load of stainless steel, I tried to calculate an acceptable margin of error, and the fat bill for stepping through the door. I wanted to bolt.

There’s still time. Maybe they won’t charge me. Or. Maybe they’ll sue me! Hahaha!

I did need dental attention; that much was certain. Further delay would exact its own price. Maybe it would only hurt. I was still sifting for some shred of solace when there came the muted click of a foot pedal, followed by the chiff and whiz of the diamond-bit drill.

I went home with one deep dental hole, one temporary filling, and a whopping dose of the bone-targeting antibiotic clindamycin. In spite of my apprehension, the procedure seemed to have gone normally. Fortunately, I still felt no pain.

*

That spring, I was mid-way through my most productive and happy season as a New York City opera singer. I was in great vocal form with plenty of high notes left in my pipes, lots of pizzazz, and I knew my way around a stage. I had solo dates on my calendar as well as my regular gig with the Metropolitan Opera Extra Chorus. But I was a low-level diva, still holding down a day job, and suddenly So suddenly! on the cusp of one of the most difficult decisions any solo singer has to face. That is, when to hang up her dreams.

There comes a point in any solo singer’s career, according to a complicated calculus of economic realities and broadening perspective, when the locus of sound and of sound reasoning begins to drift inexorably away from the stage—the rehearsals, the coaching, the auditions, the daily vocalizing, the tyranny of the common cold, the road.

After decades of wanting nothing else, my goals had begun mercifully to shift, easing my transition out of the running for principal roles. Backstage at the Met, in the final moments of the season’s last Cavalleria Rusticana, I kibitzed with a colleague, a friendly rival soprano, about doggie-daycare and skin care and the upcoming season. She seemed content in the chorister’s life. And she was a much better musician. It might be okay for me too, I dared to think, finally to be content with the extravagant privilege of having had voice enough, enough to win an insider pass to this magic castle, enough to sing for a living and enjoy a domestic mooring with a companion I adored.

I could not have known all these decisions were about to be made for me.

*

One midnight after my root canal, as I lingered in the last moments of moonlight slanting through our brownstone bay windows, the telephone erupted in a jarring clang.

“What’s wrong?” demanded a woman’s voice on the line.

“I beg your pardon. Who’s calling, please?”

“What? You just called me!” said the voice. “What’s wrong?”

“I’m sorry, I did not call you. What number are you dialing?”

Standing barefoot in my kitchen, I recognized the voice of the Manhattan endodontist. Finally, she conceded I had not paged her.

“I’m sorry. I’ve been a little blotto since my father’s funeral,” she said.

My throat tightened. Why did she think I was the caller? Was the page real, or imagined? Had she mistaken my number for that of some other patient, someone now in distress and unattended? Or was she having her own emergency? Had some other late-night caller been trying to help her manage…something? And. Really. “Blotto”?

“Oh, I am sorry for your loss,” I said, fumbling for control of the conversation, and myself. “You know, this may not be the best time for you to take on a complicated case such as this. . .”

“If you want to see someone else,” she snapped, “that’s fine, but you’ll have to pay for the work I’ve done. And a kill fee for the rest—or I’ll sue.” I was well acquainted with the term “kill fee”. But coming from a physician it sounded vaguely Kevorkian.

“I didn’t mean…It’s just that…Well, I’m sorry for your loss. Good night.”

What a wacko! What have I done?

Trembling, I hung up the phone and hurried to bed where Evie was already fast asleep. I knew I’d have to call the dentist’s bluff. In the morning I sent flowers and condolences to her office. I never paid another dime. And I never heard from her again.

I couldn’t wait to get back on the road and drive two hundred miles north to a reliable root canal at the hands of steadfast New Englanders. The price of any crowns ceased to figure into my decision. I would pay with two credit cards and grow-the-hell-up. This was to be my graduation from survival-through-creative-scavenging, which had once been a point of considerable pride. Then and there I resolved to own more of my fate.

But the nutty endodontist would not be the last such challenge we would face.

❧❧❧

Chapter 4 • Dentists I Redux

Two weeks later, I presented myself for the rest of my root canal to the busy endodontist across the field from the family dentist in Hadley, MA. He looked over my half-finished dental work—and the bump, now prominent, unmistakable, and still unaddressed. An unsolved mystery. But. Y’know. Not painful.

Setting my mind at ease, the endodontist assured me he would proceed without delay—as soon as he had the corroboration of yet another colleague down the road. It was already 4:30 on a Friday afternoon and snow had begun to fall. Everyone would be late getting home, and still, the oral surgeon agreed to see me right away.

Now we’ll get to the bottom of this, thought I with regional pride. What a relief to be in the care of competent and cooperative New England professionals.

Climbing into the oral surgeon’s hydraulic recliner, I prattled cheerfully in a New Yorker’s surrender to generous same-day service. Within minutes, the faces of the dentist and his pair of assistants became grave. All three of them, bending over me, went silent.

“Well, at least it doesn’t hurt!” I laughed.

“Let’s be sure it’s not…this…tooth,” said the affable oral surgeon, referring, I assumed, to the root canal.

Before he finished his sentence, he’d whisked away something in his tongs. Under local sedation I felt nothing, but I heard a crunchy, sucking sort of sound, followed by the abortive bonk of specimen upon lab pan. My languid thoughts skidded to familiar Gold Rush imagery—a hunk of rock drops into a prospector’s pan from the hand of Humphrey Bogart, grisly and brilliant in Treasure of the Sierra Madre; Colorado Silver King Horace Tabor strikes a lode; Puccini’s Girl of the Golden West, of course…Looking into the drawn faces above me, I reckoned the oral surgeon looked a bit bristly. Bogie desperatelypeering into his dry sluice. . .

“Okay, we’ll have this tested and get back to you,” said Bogie, breaking character to cement a pair of temps. Still I had no sense of bone, tissue, or tools that added up to trouble. I left the office confidently to await my permanent crowns.

*

While in town I took time for a quick visit to my parents, at rest in their shady corner of Wildwood Cemetery. My visits to Wildwood, I privately confessed, had become increasingly perfunctory, even reluctant. The graveyard commonplace of fixed stone and barbered lawns never satisfied my teeming memory and thirsty heart. I loved the memorial verses and the roughhewn morning-rose granite of the marker we had chosen. But always, within moments, I recalled the wrangling over material costs (Do we really need to include her middle name?), and the literalist engraver, who somehow understood my instruction to add my Mom’s inscription “at the bottom” to mean “right on the bottom edge where it will forever after be buried in grass clippings and forgotten”.

My mother had been a classical singer and my best booster, until her death, exhausted by diabetes at sixty-four, in 1990. Alas, I had bloomed too late to enjoy my successes with her. When I crowed to my father about my new job at the Metropolitan Opera in 1994, he wondered aloud, “So you’ll be a secretary…or…what?” Of course, to fault my father for this brand of cluelessness would be futile. But to thrill my mom with the news would have been deeply gratifying.

My father passed away less than three years later, in the spring of 1996, too soon but not unexpectedly. I missed him too.

I hopped onto the highway back to Brooklyn, only incidentally wondering what would happen next.

❧❧❧

Chapter 5 • Then What?

The dental drama subsided while we awaited my test results, and Evie and I returned to our happy status quo for a couple of weeks. Evie juggled legal taxonomies. Our pair of sibling tabbies did silly, endearing things, daily refreshing us, Evie especially. I returned to my day job as a magazine assistant art director, and by night, I took my turn on the Metropolitan Opera stage.

*

Most Extra Choristers come to both rehearsals and performances directly from our day jobs, briefcase or messenger bag in hand. One baritone I knew took to his cell phone whenever possible, to resume brokering real estate deals. Between cues, an alto beside me often pulled out a red felt-tip and a folder of first drafts.

Veteran Regular Choristers have many ways to occupy off-stage downtime, notwithstanding a strict morals clause in the bylaws of a job which, after all, entails recurrent states of partial undress. A few guys I knew carefully hung up their costumes to join a standing dressing-room poker game in their undershorts, while principals onstage engaged in love, death and high notes. Some took to their cubbies to finish household paperwork or study upcoming scores. Others snuck a shot of schnapps. But in my first season, I always watched the stage from the wings, intoxicated by the nearness of world-class artists on every side, all evening long.

“The child is alive!” whispered a tenor friend, watching me gawk.

And so she was. In one extraordinary performance, during a long scene for principals only, I found myself alone backstage, behind the fantastical three-story-high Zeffirelli set for Puccini’s Turandot, as international superstar Placido Domingo began the famous “Nessun dorma”. I had to tear myself away to hurry into my next chorus position. My path took me across a wide vault of darkness, relieved by a faint spillover of light from the stage door.

Out on stage, Mr. Domingo was coming into the stretch, orchestra mounting beneath his voice, urging onward, “Vincero-o-h…,” gathering upward, “Vincero-o-o-h…,” finally resolving, “Vi-i-i-n-[atch]-E-E-E-E-EH-r-o-o-o-o-h!” A frenzy of applause and bravos bested Puccini’s triumphant orchestral coda.

Behind me, sheer ecstasy burst over the pit, over the tenor and into the wings. Before me, the stage door swung open. Silhouetted in the backlight from the hallway was Dame Gwyneth Jones, Ice Princess of the evening, in resplendent costume and bejeweled headdress, her silky sleeves spread wide upon the doorjamb. I had the fleeting impression the explosive applause was for her, rather than the tenor, and the roaring ovation, my own bliss flowing toward her.

Dame Gwyneth checked her step as I veered aside, grateful to be swallowed in shadows. She continued to her marks as I did to mine, sealing for me what seemed the epitome of Gesamtkunstwerk—Wagner’s coinage for grand opera—the all-embracing alchemy of High Art and Artists, altogether, all at once. And proving to me that I was exactly where I was meant to be.

“The money” was definitely not “the only reason to take this job”.

*

As I waited for my next dentist appointment, I began preparing my annual Met re-audition, coming up in three weeks. One evening, routinely checking the answering machine on the shelf by the brownstone galley kitchen, Evie and I heard the subdued voice of the New England oral surgeon:

I apologize for my delay in calling and for delivering this important news in a recording, but I believe you need to know that you have cancer, and time is of the essence.

Evie blanched. I equivocated, remaining calm. Weirdly calm. I returned the call.

“I used my privileges at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology to confirm your diagnosis before calling,” said the oral surgeon, explaining the delay. He had spared me a costly time-sink of inconclusive analyses. “Thank you, Doctor,” I said, a line of dry recitative, advancing the plot.

He read to us from the pathology report:

Well-differentiated chondrosarcoma…low-grade malignant proliferations…Most unusual…possible extension of a neoplasm into the gingival tissue…Deeper excision of the bone…Additional neoplastic tissue.

I wasn’t following very well. But his words began to add up.

“So, you’re saying. . .”

“You have cancer.” He had mentioned cancer before, I guess, but…

Cancer? Hmm…Cancer. Geez.

“Well. Thank you, Doctor,” I said with unnatural detachment, trying to match his gravitas. “So…What now?”

“Oh! Why,” he cried, “you have to get to a head and neck surgeon! Right away!”

“Yes, of course,” I said. “Thank you, Doctor.”

He said goodnight warmly, with a reminder not to delay.

A head-and-neck-surgeon. Is that even a thing? Do people know about this?

I heard the term only in a category of oddness. Head and Neck Surgeon. Big and Tall Men. The Great and Powerful Oz. Wherever would I find one?

On television at the time, the President of the United States was giving evasive answers to impertinent questions about his skeevy sex life. Absurdity was everywhere. And I had no idea how to play my part. I hung up the phone and turned to Evie. She looked small across the room, gathered into herself, and pale, her rosy accents gone gray.

“What now?” I repeated.

*

During the last year of my mother’s gruelingly protracted illness, my father briefly made a practice of calling me at my day job in Manhattan. A casual chat at lunch time, just to check in, though we had never chatted casually, ever, in our fraught relationship. He kept me abreast of developments at home, and of how he was holding up, caring for my mother mostly by himself.

On the day my mother died, my father said into the telephone, with his essential preciseness, “Kath. Your mother stopped breathing at one o’clock.”

His inflection betrayed the daily domestic strain, but nothing unusual. I’d grown accustomed to a measure of martyrdom in my father, not wholly undeserved, I grant—after long years of my mother’s struggle with Type 1 diabetes, the relentless cycles of hope and disappointment, collapse, and recovery, spiraling ever downward.

That day I didn’t grasp his meaning. Fumbling for phrases to wrap up our make-believe father-daughter chat, my mind full of childish resentments, I heard myself say,

“Yeah? Hmm. And then what?” And then what!

It was crushingly inappropriate, but I simply had not understood. My Dad’s delivery of this shattering news sounded so like the many times before when he had overstated my mother’s latest emergency, almost willing her deliverance—and his own. I was sure he would go on to tell me her breathing had resumed within minutes without intervention. I even braced to hear him say he’d saved a few dollars by cutting back on the home health aides’ hours that week.

“Well, she’s dead!” choked my father, gorge rising in a noise unfamiliar to me, sounding something like surrender to an old and bitter foe.

I thought of the Witch’s Castle troops in MGM’s Oz, the craggy Captain of the Winkie Guards, in his ridiculous uniform, gazing up from his knees beside the puddle of the Wicked Witch of the West. She’s dead! Frightened. Amazed. Delivered. But too craggy and formerly mean to evoke much sympathy for himself.

“And then what,” I had said into the yawning abyss of my father’s loss. The surprise and helplessness in his voice chastened me, and splintered my heart.

And now, to the physician whose lot it had been to deliver my death sentence, I had said, almost as carelessly, “What now?”

❧❧❧

Book II

Prepped and Draped

The voice in performance

is not disembodied or transcendent; it is anchored in

the real, and fragile, human body.

—Dr. Michael Hutcheon and Linda Hutcheon

Bodily Charm: Living Opera

In writing,

the risk is all the author’s.

In surgery, it belongs to the human being

lying on the operating table.

—Richard Selzer

The Whistlers’ Room: Stories and Essays

Chapter 6 • Head Shots

One study published in the Journal of American Medical Arts found the cardiovascular fitness of singers at New York City Opera comparable to that of marathoners from the New York Road Runners’ Club. The article compared the doggedness of singers’ regimens to the single-mindedness of serious athletes. My singer’s lifestyle always became more comprehensible to others when I compared it to an athlete’s commitment of body, soul, and daily schedule. I hailed this clinical corroboration and spread it around liberally.

At the same time, the singing life often seems to be all about appearances—even then, light years before the current age of social media, when aspiring performers are expected to present a fully produced video performance package merely to gain entrance. The year cancer came for me, performers built their promo material around a couple of dramatic 8 X 10 black-and-white glossies, one full-length and one from the neck up.

In an all-day shadow of perpetual scaffolding at 47th and Broadway, the studio where I’d taken my most recent head shots was frankly seedy, and dead center of the theater district, where nothing stands in the way of good promo pix. My hair, for example, shorn too short the day before my scheduled shoot? Irrelevant. Studio pros happily brushed and yanked and glued the remaining inches into fabulous submission, shot-by-shot. They saw to it that my thin-ish lips bloomed ripely in the hollows of appled cheeks. My green eyes danced with sugar and sass under come-hither fringes. My smile was a stockade of shiny pickets.

“You know,” they said, “your makeup has to be completely different for black-and-white. Don’t worry how you look right now. . .”

The seasoned seductress at the desk had lured at least a generation of Broadway babies with thrilling confabs of celebrities in their salad days, whose glossies papered the wall behind her. She’d sold me, for one, on not only the hair and makeup service, but also the optional retouching package.

“Let us brush out your little lines today, and in five years when you need new pictures, bring these back to us, and we’ll erase the retouching. Voilà. No charge! Okay Hon?”

She was flipping through my proofs as I pulled out my checkbook. “Ooh, that’s a beauty,” she purred. I collected my package and turned to go.

“Don’t call, Hon,” she called after me without looking up. “We’ll call you when they’re ready. . .”

Did she just say don’t-call-us-we’ll-call-you? Seriously?

“…Good lu-u-u-ck!” she sang, recording my payment.

Sooner than expected I would need new head shots. By March of 1997, hair and makeup would cease to matter altogether.

*

Computed Tomography (CT or CAT) scans produce films of the body’s insides that help identify mysterious phenomena without having to open it up. Images must be clear, well-framed, unobstructed, and include arcana like the small metal disc placed in a corner, distinguishing left from right. CT scans must be “read” by a radiologist who knows precisely how things ought not to look, as surely as how they ought to, and who can recognize this wily slimeball, my tumor, in an infinity of guises. The radiologist does not act, but rather reports—accurately, objectively, unflinchingly—the signposts of the interior that become the surgeon’s GPS.

But neither Evie nor I knew anything of radiologists or craniofacial surgeons. We needed a higher power. We turned to Evie’s wealthy and eccentric cousin, Bernice.

Heir to a fortune accumulated through war-time merchandising, Bernice found 1950’s Manhattan wide open to her theatrical aspirations. Her wealth authorized her to help shape the scene both as participant and as doyen, gradually acquiring a couple of fabled theaters, and several prime SoHo properties. Nevertheless, the vicissitudes of several cruel decades had wounded Bernice, scarred and toughened her, accruing for her a legacy as much of irascible withholding as of generous embrace. Long ensconced in SoHo, her gentler sister Pearl her only intimate, Bernice could be terrifying. One never knew. But it was worth a try.

As it happened, our phone call found Bernice in a good mood. In fact, a certain serendipity seemed to follow us after my dental debacle. Now Bernice referred us directly to a head and neck surgeon of her acquaintance. He was out of town, but on the strength of Bernice’s introduction, he immediately called in referrals for my crucial baseline CT scans. Diagnostic Radiology Associates in Manhattan expected us within the hour. In less than a day I had received a diagnosis of chondrosarcoma and lined up dozens of head shots. In time, this process would become routine, but that day it was one of mysterious coincidence and the kindness of strangers.

*

On TV the President of the United States was trying to fend off impeachment, bested by an embittered blonde Washington wageworker, wearing a wire no less, on behalf of a besotted West Wing intern. This ignoble national moment is pegged permanently to the beginning of my adventure in the parallel universe of serious illness.

That first day Evie and I made our way to Diagnostic Radiology Associates, in the rain, jackets flapping in the brisk late-winter wind, chatting mordantly. A chunky blonde of hard-bitten mien plunged past us in the crosswalk.

Does she look familiar?

“Hey, wait,”I whispered.“Keep it down! She could be wearing a wire. Hahaha!” We were crossing a wide-open section of Greenwich Avenue where the One-and-Nine Local stops, below Chelsea but above the famous walkups and cobblestones of the Village. Ideal for subterfuge. Schlepping beside me, squinting under a spitting March-gray sky, Evie wasn’t laughing.

C’mon that was a good one! I was miffed. The rain began to fall for real, and we picked up our pace in silence.

*

What little I knew about X-rays I had learned from Superman and my wisdom teeth—they reveal bone within flesh by using small amounts of radiation, which could be hazardous, but not like The Bomb, and a lead planter will block them. CT scans are something else again. This Nobel Prize-winning process combines X-ray technology with computers to produce 360º cross-sectional views of the subject. A CT scan images bone, soft tissue, and blood vessels concurrentlyin a fast, painless procedure already commonplace in the field. Doctors routinely consult CT scans for accurate diagnoses. But I had a moment’s pause when the radiologist read out the order, including “coronal and axial” scans, “with contrast and without”.

“‘Coronal and axial’ refers to the direction of the X-ray beam—top to bottom or side to side,” he explained. Ok, fine.

“And ‘contrast’is the radioactive dye injected into the venous bloodstream circulating through the heart, into the arteries, all the capillaries, and back to the heart.” So…radiation flowing pretty much everywhere inside of me. . .?

I balked.

I needn’t have.

The injection is a clear solution consisting primarily of iodine, a naturally occurring mineral which blocks the X-ray beam in certain tissue types. Those areas appear to “light up” in the resulting image, revealing finer details than X-ray alone, and more accurate diagnosis.

Intravenous iodine is considered safe, and well worth any minor risks. One unadvertised side effect can be a sensation of warming as the solution circulates. This subtle but distinct bloom of radiant heat is pleasantly detectable as it flows into the body’s most responsive tissues in succession. First the fingertips, then the sensitive palms, the lips, the tender nasal and buccal mucosa, and eventually, the tenderest tissues of all…Yesssss…

A common patient experience, it nevertheless made me blush. I kept to myself. . .no one must ever know…how I anticipated the moment when a miniature arm-gurney would swing out from below the scan-bed, as the technician says, “Relax your arm,” and straps it down. “Now you’re going to feel a little prick,” she continues, whereupon follows the travelling glow.

So began my long road through the landscape of illness. Over time, my file looped back and forth through the Radiology Department, growing ever thicker. Lots of pictures. Inside. Outside. X-rays. CTs, MRIs, PET scans. And because the sophisticated machines require lowered ambient temperatures, a cozy flannel blanket was always a warming-oven away.

My favorite was Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). Radiation- and guilt-free, the rhythmic hum and clacking percussion of spinning magnets became my unlikely lullaby, rocking my senses into an hour of peace, lying down and posing for pictures.

BANG. Pause. BANGBANGBANG. Pause. Kalock. Pause. Pause. Kalockkalockkalockkalock. Pause. Pause. BANGBANGBANG. Kalock. Pause. Kalock. Pause. Kalockkalockkalock…

“Are you all right in there?” calls the technician, peering into my giant cocoon. “What’s your favorite music?”

They pipe it in. My own playlist included Mozart, Bach, and if they had it, Brubeck. You can choose your own, or none at all.

Don’t be frightened. People in the Land of Illness! Embrace this!

An MRI is nothing to fear. Let them tuck you into a warm flannel blanket. Relax. And, if I may, try the Mozart.

❧❧❧

Chapter 7 • Meeting the Big C

We discovered with what dispatch a properly authorized, dedicated facility could get the job done. That same afternoon we carried a thick portfolio of the all-important films with us to meet the referring doctor, Cousin Bernice’s pal, fresh from his vacation. This was our first real cancer consult. In a classic wood-paneled office the doctor purled out a steady string of easygoing sentences, filling the minutes it took him to read through the single-page radiology report, and orient himself in the stack of my latest head shots.

When he was ready, he said something like: “Oftentimes, tumors originating in the lower midface may be treated by lesser measures, preserving the cheek complex, the nose and most of the eye socket. The precise limits of the resection of course are determined by the tumor. . .”