13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Every year many thousands of racing greyhounds retire from the racetrack and are successfully re-homed through dedicated greyhound charities. Written in association with Greyhound Rescue West of England, Retired Greyhounds - A Guide to Care and Understanding is essential reading for anyone who owns, or is thinking of owning a retired greyhound.The sound and practical advice contained within these pages will ensure that you have a clear understanding of your dog's needs, and will help to enable successful communication between you and your dog, thereby avoiding the common pitfalls that can arise through misunderstanding.Contents include:The first few days; Day-to-day care; Problem solving; Health care; Training for obedience; Fun and games. Approximately 10,000 greyhounds retire from racing each year and are re-homed by numerous dedicated retired greyhound charities.This book provides valuable insight and practical instruction to ensure that new owners are able to make a success of their new partnership through correct care and understanding.Written in association with GRWE - Greyhound Rescue West of England.Fully illustrated with 93 colour photographs and 2 line diagramsCarol Baby has worked as a volunteer for GRWE for over ten years.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 194

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

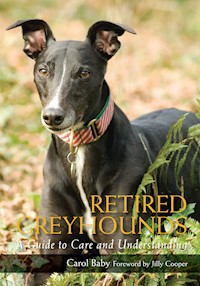

This lovely greyhound bitch shows what beautiful dogs greyhounds are.

RETIRED GREYHOUNDS

A Guide to Care and Understanding

Carol Baby

Foreword by Jilly Cooper

Copyright

First published in 2010 by The Crowood Press Ltd, Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book edition first published in 2013

© Carol Baby

All rights reserved. This e-book is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 978 1 84797 505 8

Illustrations by Charlotte Kelly, based on original artwork by the author

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Jilly Cooper

1 The Greyhound Breed

2 The Background to a Racing Greyhound’s Life

3 Is a Greyhound for Me?

4 The Adoption Process

5 The First Few Days

6 Day-to-Day Care of your Greyhound

7 Health Care

8 Games

9 Problem-Solving

10 Obedience Training

11 Responsible Greyhound Ownership

Appendix 1: Greyhound Rescue West of England

Appendix 2: Understanding a Dog’s Racing History

Further Information

Index

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks to Liz Rodgers who worked tirelessly with me on the photographs, and Nick Guise-Smith for donating racing photos so that all proceeds from the book could go to Greyhound Rescue West of England.

Thank you also to Carol Forde and Barry King for advising on Chapter 2, and to the Somerset homing team from Greyhound Rescue West of England, and Anne Pullen, for support and proof reading. Thank you to Sandra Morris for inspiring me to learn about how dogs think and communicate, to Kay Andrews and Ann Morgan, and my husband Bob, for believing in me.

FOREWORD BY JILLY COOPER

My greyhound, Feather, who came to us through GRWE, had a terrible start in life. In the middle of winter he was turned out in a muzzle on a motorway in Ireland. Unable to eat, drink or fend off other dogs, it was three weeks before he was found. Somebody had also tried to burn the racing tattoos off his ears. But despite this dreadful experience, he has proved the most lovely, affectionate, charming, biddable, kind dog we have ever owned, who also keeps us in fits of laughter.

JillyCooper with GRWE dog Heather.

Many greyhounds have appalling lives once their racing life is over, or when they are no longer any use for breeding. Some of them are just chucked out, like Feather, or receive a bullet through the head or end up in desperately over-crowded kennels or, worst of all, are sold to run their hearts and bodies out for incredibly cruel trainers on tracks abroad.

All this should never happen, because greyhounds make the most wonderful pets. Some of them obviously need training when they come to their new owners straight off the racetrack.

In this lovely book, the very knowledgeable Carol Baby will take you on a most rewarding journey. She will tell you how to find the right dog; how to introduce it to the strangeness of domestic life, how to house train it; teach it to play and have fun; teach it to get on with other dogs and cats and to give infinite pleasure to children. Few dogs are more charming with children than a greyhound. Feather always causes shrieks of joy from my grandchildren, when he takes off and races round and round the field or big lawn just for the fun of it.

Greyhounds are equally miraculous with older people. My husband Leo, who has Parkinsons, is unsteady on his legs. Feather never pulls on the lead and slides past him like a skein of silk – but admittedly steals his reclining invalid chair at every opportunity!

This is a lovely book. Carol Baby does not pull any punches that anyone rescuing a greyhound will need time, patience and above all love, but it is a worthwhile adventure and I am convinced if you follow Carol’s guidance you will end up with a glorious dog.

Jilly Cooper, 2010

1 THE GREYHOUND BREED

BREED DESCRIPTION AND CHARACTERISTICS

There is no doubt in greyhound lovers’ eyes that they are the most beautiful dogs, long-legged, streamlined and elegant, sleek and dignified – but the beauty is not just skin deep. Greyhounds are gentle and affectionate, quiet and loyal, calm and loving. It is a pleasure and a privilege to have one living in your home.

The fifteenth-century Boke (book) of St Albans characterized the greyhound as ‘headed like a snake, neckewd like a drake, backed like a bream, tailed like a rat, footed like a cat’. This makes the breed sound like bits and pieces of different animals put together without thought, but a greyhound is far better designed than that. However, the quote does tell us that people were writing ‘breed standards’ for ancient breeds such as greyhounds as far back as the fifteenth century!

The author with her lurcher, Ash, and ex-racing greyhound Foxy.

Beauty in greyhounds is not just skin deep: kindness shines out of those eyes.

Racing greyhounds are bred purely for their ability to race and win, rather than for looks. This is what keeps the breed healthy, as dogs with inbred defects are unlikely to be winners. Well bred racing greyhound pups will be sold for between £3,000 to £10,000, and an already proven dog will sell for upwards of £20,000; the price tag therefore acts as an incentive to make sure that no inherited defects are apparent in racing greyhound stock. So when you take on an ex-racing greyhound it is unlikely to have any predisposed inherent defects, and it will have a long pedigree, including winners. Racing greyhounds tend to be smaller than show greyhounds, and are not bred to Kennel Club requirements. However, I have included the Kennel Club breed standard, as it is interesting to compare your ex-racing greyhound and see how it matches up.

THE KENNEL CLUB BREED STANDARD

A Breed Standard is the guideline which describes the ideal characteristics, temperament and appearance of a breed and ensures that the breed is fit for function. Absolute soundness is essential. Breeders and judges should at all times be careful to avoid obvious conditions or exaggerations which would be detrimental in any way to the health, welfare or soundness of this breed. From time to time certain conditions or exaggerations may be considered to have the potential to affect dogs in some breeds adversely, and judges and breeders are requested to refer to the Kennel Club website for details of any such current issues. If a feature or quality is desirable it should only be present in the right measure.

General Appearance

Strongly built, upstanding, of generous proportions, muscular power and symmetrical formation, with long head and neck, clean well laid shoulders, deep chest, capacious body, slightly arched loin, powerful quarters, sound legs and feet, and a suppleness of limb, which emphasize in a marked degree its distinctive type and quality.

Characteristics

Possessing remarkable stamina and endurance.

Temperament

Intelligent, gentle, affectionate and even-tempered.

Head and Skull

Long, moderate width, flat skull, slight stop. Jaws powerful and well chiselled.

Eyes

Bright, intelligent, oval and obliquely set. Preferably dark.

Ears

Small, rose-shape, of fine texture.

Mouth

Jaws strong with a perfect, regular and complete scissor bite, i.e. the upper teeth closely overlapping lower teeth and set square to the jaws.

Neck

Long and muscular, elegantly arched, well let into shoulders.

Forequarters

Shoulders oblique, well set back, muscular without being loaded, narrow and cleanly defined at top. Forelegs, long and straight, bone of good substance and quality. Elbows free and well set under shoulders. Pasterns of moderate length, slightly sprung. Elbows, pasterns and toes inclining neither in nor out.

Body

Chest deep and capacious, providing adequate heart room. Ribs deep, well sprung and carried well back. Flanks well cut up. Back rather long, broad and square. Loins powerful, slightly arched.

Hindquarters

Thighs and second thighs wide and muscular, showing great propelling power. Stifles well bent. Hocks well let down, inclining neither in nor out. Body and hindquarters, features of ample proportions and well coupled, enabling adequate ground to be covered when standing.

Feet

Moderate length, with compact, well knuckled toes and strong pads.

Tail

Long, set on rather low, strong at root, tapering to point, carried low, slightly curved.

Gait/Movement

Straight, low reaching, free stride enabling the ground to be covered at great speed. Hindlegs coming well under body giving great propulsion.

Coat

Fine and close.

Colour

Black, white, red, blue, fawn, fallow, brindle or any of these colours broken with white.

Size

Ideal height: dogs: 71–76 cms (28–30 ins); bitches: 69–71 cms (27–28 ins).

Faults

Any departure from the foregoing points should be considered a fault and the seriousness with which the fault should be regarded should be in exact proportion to its degree and its effect upon the health and welfare of the dog.

(Copyright The Kennel Club. Reproduced with their permission.)

An ex-racing greyhound is like a retired Olympic athlete: remember what it is you have on the end of that lead! (photo provided by Nick Guise-Smith www.mirrorboxstudios.co.uk)

A greyhound is often referred to as a ‘sight hound’ or a ‘gaze hound’, which means that it uses sight more than its other senses to detect prey. Greyhounds have very keen sight and often spot prey long before we do. Other breeds that are classified as sight or gaze hounds include whippets, Salukis, borzois and Afghans, but the greyhound is the fastest of them all. The only animal faster than a greyhound is a cheetah. So when you take a retired greyhound into your home you have the privilege of taking in the equivalent of an Olympic athlete. You will be surprised how calm and docile they are in the house – but when you take them out, remember what it is you have on the end of that lead!

BREED HISTORY

The greyhound is one of the most ancient breeds of dog, produced by man’s selective breeding for hunting animals such as the hare and the gazelle. Bones and teeth from archaeological sites and pictures painted on ancient pottery, pillars and tablets from Middle Eastern countries indicate that greyhound-type dogs were common there at least three thousand years ago, some say as far back as seven thousand. Similar dogs appear in artwork across Europe from medieval times. And yet the breed remains robust, sharing common ancestry with Arabian dogs such as the Saluki, the Pharaoh hound and the Slughi.

As the Roman Empire spread across Europe the greyhound came too, reaching England in the sixth century. Rich and poor families would have had such dogs to help provide food for the pot. Then in 1014 – during King Canute’s reign – a law was produced that ‘No meane man may own a Griehound’, a sentiment many of us agree with, although the word ‘mean’ in this case actually means ‘poor’. (It strikes me that Canute knew more about dogs that he did about the sea!) Only noblemen were then allowed to own greyhounds, which shows how highly prized they were (it is sad that in this and the last century that has not always been the case). This eventually led to the change in emphasis from hunting with greyhounds for food to hunting for entertainment.

In the sixteenth century coursing rules were drawn up by the Duke of Norfolk. In the eighteenth century greyhound racing meets became popular for greyhound owners, and they are still popular to this day, reaching their highest popularity in the years just after World War II.

SAINT GUINEFORT

There are many wonderful European legends about hounds’ deeds and bravery. Gelert’s story inspired many of us as children, and his grave can be seen at Beddgelert in Snowdonia, Wales. The story relates that Gelert was a wolfhound rather than a greyhound, but there is a surprisingly similar story of a greyhound called Guinefort, a thirteenth-century French tale in which Guinefort came to be regarded by the local people as a saint.

As in most of these legends, Guinefort’s owner, a French knight who lived in a castle near Lyons, went out leaving his faithful greyhound to guard the baby. While he was gone a venomous snake came into the solar and slithered on to the baby’s crib. Guinefort leapt into action, attacking the snake. In the mêlée the crib was knocked over and the baby landed safely underneath, while Guinefort killed the snake.

When the knight returned he saw the upturned crib and the dog with blood on its lips, but he did not see the baby hidden under the crib. He immediately jumped to the conclusion that Guinefort had killed the baby, and in fury drew his sword and killed his dog. Then he heard the baby cry and found the body of the snake, and realized what an awful deed he had done.

Filled with remorse and gratitude the knight and his family took the body of the dog to a disused well by the forest and placed it in there. They covered it over with stones and planted trees round it, making it into a shrine. The local people came to regard Guinefort as a saint for the protection of children, a belief which continued right up until the early twentieth century, and they would bring children to his shrine to be healed. The Catholic church never recognized him as a saint, however, maintaining that no dog could possibly be a saint.

Many of these legends abound, and they are all startlingly similar. It is difficult to know whether there is any truth in them, or whether they were cautionary tales (the moral being, ‘Don’t jump to conclusions until you have found out the whole story’). You can visit Gelert’s grave at Beddgelert in Wales, which lends some truth to the story, but the gravestone is obviously more recent than mediaeval times. Sadly during World War II Guinefort’s shrine fell into disrepair, and is now lost deep in the woods somewhere in France. Maybe I will go and find it one day.

Nevertheless, the fact that all these stories were about faithful hounds helps us to realize how loved and revered these dogs were so long ago, and it confirms our knowledge that these are wonderful dogs with a superb temperament, and which deserve the very best that life alongside humans can give them.

THE ORIGIN OF THE BREED NAME

Different reasons are given for the origin of the name ‘greyhound’. Some say that all the early ones were grey and the colour variations developed later. It is interesting that Belayev, a Russian geneticist in the last century, experimented with breeding silver foxes selectively to improve tameness and ease of handling. These foxes were being bred for their pelts on fur farms, but were very difficult to handle. Over only eighteen generations, as the temperament improved, all sorts of colour variations mysteriously appeared in the breed. Did something like this happen to our greyhounds?

Another theory is that the word ‘grey’ is derived from the Latin word gradus meaning ‘grade’. Dr Caius, the eminent sixteenth-century Cambridge physician, wrote:

The greyhound hath his name of this word gre; which word soundeth gradus in Latin, in Englishe degree, because among all dogges these are the most principall, occupying the Chiefest place, and being simply and absolutely the best of the gentle kinde of houndes.

‘Simply the best’ – I’ll go along with that idea!

Bo Jangles, Liz the photographer’s dog, a really handsome greyhound – ‘Simply the Best’.

2 THE BACKGROUND TO A RACING GREYHOUND’S LIFE

GREYHOUND WELFARE

The conditions under which a greyhound is produced can vary hugely from being born and kept alone in a cold, cheerless shed in someone’s back garden, through to a state-of-the-art racing kennel with underfloor heating, double glazing and every conceivable luxury a racing dog might need. The biggest training yards can have from sixty to a hundred dogs at any one time. Most owners and trainers want the best for their dogs and take huge pride in breeding them and keeping them in tiptop condition ready to win. But, as in all sports, there are the rogues who will cut corners, save money, and who have little real affection for the dogs except as money-makers. These people have given the sport a bad name.

Some racing greyhounds are kept in cold, cheerless sheds in the trainer’s back garden…

In May 2002 the ‘Charter for the Racing Greyhound’ was produced in response to a debate on the sport in the House of Lords in the previous year. A sixteen-point plan was produced by the Greyhound Forum, which was made up of representatives from various animal welfare charities together with the British National Racing Board (now called the Greyhound Board of Great Britain) and various racing bodies. It has helped to make a start in improving the life of greyhounds during and after racing – but there is still a long way to go. It covers the basic requirements of a living animal, which should hardly need to be spelled out in the twenty-first century, and offers recommendations as to the manner of a greyhound’s death: this should be done humanely by a veterinary surgeon, and only when destruction is inevitable.

…while more fortunate ones live in state-of-the-art kennels with heating and double glazing.

It also discourages the over-production of greyhounds through indiscriminate breeding, although this is such a vague requirement that there is no way to enforce it; indeed there have been many cases highlighted recently of wholesale slaughter, where some layman has illegally shot unwanted dogs and buried them in his back yard.

It is a good charter and a real step in the right direction, but how do you quantify its success? And how do you enforce it?

Greyhound pups are just as curious and mischievous as pups of any other breed.

THE GREYHOUND CHARTER

The registered owner and/or keeper of a greyhound should take full responsibility for the physical and mental well-being of the greyhound and should do so with full regard to the dog’s future welfare. All greyhounds should be permanently identified, properly registered, and relevant records kept by owner and/or keeper.All greyhounds should be fully vaccinated by a veterinary surgeon and provided with a current certificate of vaccination. All greyhounds must be provided with suitable food and accommodation and have unrestricted access to fresh clean water.Adequate arrangements must be made to allow for exercise and socialisation.Breeding and rearing – the over-production of greyhounds through indiscriminate breeding – must be avoided. Where a racing greyhound is bred from, the long-term welfare of the bitch and puppies must be paramount. Training must be conducted so as to safeguard the long-term welfare of the dog.Where destruction is inevitable, greyhounds should be euthanased humanely by the intravenous injection of a suitable drug administered under the supervision of a veterinary surgeon.When transported, all greyhounds should be maintained in safety and comfort.All tracks should appoint a member of staff responsible for animal welfare.A supervising veterinary surgeon must be present whenever greyhounds are raced at tracks.Tracks and kennels must be designed and maintained to ensure the highest welfare standards for the racing greyhounds.Greyhounds must only race if passed fit by a veterinary surgeon immediately prior to racing.Greyhounds must be entitled to receive emergency veterinary care if injured.Drugs which may affect the performance of a greyhound when racing should not be permitted.The industry must endeavour to ensure that all race courses have in operation a properly funded home-finding scheme for retired greyhounds. Such schemes should work closely with other welfare and charitable bodies seeking to find good homes for exracing greyhounds.(This charter is credited to the Greyhound Forum and must be read in conjunction with the code of practice available from the Defra web site www.defra.gov.uk/corporate/consult/greyhoundwelfare/index.htm).

A greyhound bitch will produce a litter of around six to ten puppies, but only about 60 per cent of them will make it into racing. Those that are not going to make the grade are usually handed to rescue charities or are euthanased before they are a year old. Those that enter the charities as pups are good ones to choose if you have a cat, as they are usually young enough to learn to live safely and happily with it.

The pups will grow up in their family unit, which means they do learn to socialize, but as they will live only with greyhounds throughout their racing life they can find it difficult to socialize with other breeds of dog at first, and have little experience of the world outside their limited environment.

EARLY TRAINING

The age that greyhounds begin their training is around fifteen months old for a bitch and seventeen months old for a dog. If the young dog is very big this may be delayed for a few months to avoid putting excess strain on its limbs. The dog’s keeper will have been watching its response to chase situations as it grows up, and will have a good idea of how keen it is going to be. By this time pups that show no interest at all in the chase will have been weeded out.

A beautiful greyhound bitch with her litter of puppies.

The dogs are taught to walk calmly on the lead without pulling. Lead-walking is a major part of their training regime, and in a large kennels one person may be walking two or three dogs at once. Given a racing weight of around 28kg to 36kg (62lb to 79lb) for each dog, and you can see why it is important that they walk well on the lead.

The young dogs will be put through a fitness programme that generally takes about six weeks. A local trainer’s regime (borrowing terms from the horse world) goes something like this: first they will walk a mile every day for ten days, then go on to two miles a day for ten days. Then they will move on to trotting these distances – often the trainer will use a bike to ride alongside them. When they can trot a mile without panting they will move on to full gallop, often using a track to run on and a man-made lure to chase. The training lure is usually made of a sack tied to a cable, on a reel. Just lying on the ground this would have no real appeal for the dog: it is the fact that it moves that makes it alluring, which shows you how strong the chase instinct is in these dogs.

As the trap opens he steps tentatively out…

… catches sight of the homemade lure being pulled swiftly ahead of him…

…and then he is off…

The excitement builds up as he chases the lure, gathering speed as he goes

A seventeen-month-old greyhound is introduced to the traps for the first time at the trainer’s kennels.

After successfully chasing the lure the greyhound is rewarded by being thrown a soft toy to play with. In his excitement he will probably rip it up.