Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Flint

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

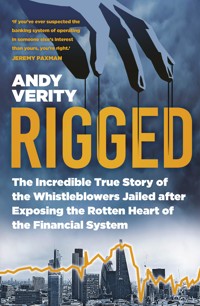

Rigged exposes a cover-up at the highest level on both sides of the Atlantic, upending the official story of the biggest scandal since the global financial crisis. It picks up where The Big Short leaves off, as the dark clouds of the financial crisis gather. Banks' health is judged by an interest rate called Libor (the London Interbank Offered Rate). The higher the Libor, the worse off the bank; too high and it's goodnight Vienna. Libor is heading skywards. To save themselves from collapse, nationalisation and loss of bonuses, banks instruct traders to manipulate Libor down – a criminal practice known as lowballing. Outraged, traders turn whistleblowers, alerting the authorities. As Rigged reveals, their instructions come first from top bosses – then from central banks and governments. But when the scandal explodes into the news, prosecutors allow banks to cover up the evidence pointing to the top. Instead, they accuse 37 traders of another kind of interest rate 'rigging' that no one had seen as a crime. In nine trials from 2015 to 2019, nineteen are convicted and sentenced. Rigged exclusively shows why all the defendants are innocent, and how any real culprits go unpunished. How could this happen? Turns out, it's not just the market that's rigged. It's the entire system.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 705

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR RIGGED

If you’ve ever suspected the banking system of operating in someone else’s interest than yours, you’re right. It is a world of clever, amoral young people endlessly searching for ways to bend the rules. We badly need men in white hats to control them. Verity mercilessly demonstrates we ain’t got ‘em. Andy Verity is a reporter’s reporter. If only there were more like him.

– JEREMY PAXMAN

Andy has always been an uncompromising journalist, and he’s fought to tell a dystopian tale of a lowballing scandal at the top of financial society. I suspect reading the details will be eye popping.

– MARTIN LEWIS

A brilliant and compelling account of a huge establishment cover-up. The stories of low-level traders who found themselves expendable are brutal and heart-rending. I was prepared to hear that the big beasts of the banking world protected themselves at the expense of those further down the food chain, I was less prepared for the revelations that official UK institutions appeared to contribute to the miscarriages of justice Verity brings to life.

– VICTORIA DERBYSHIRE

One of the most powerful and shocking stories I’ve ever read – a real blood-boiler. Andy Verity, one of the BBC’s top financial reporters, exposes with shining clarity one of the greatest scandals of modern times ... in a modern-day version of the Salem witch trials, the financial and political establishment in Britain and America worked together to ruin the lives of low-level City traders. They were sentenced to huge jail terms for crimes which were at best minor, and may never have committed at all. Meanwhile famous and powerful figures in the City and Whitehall, who seem to have committed far worse offences, escaped unscathed. This book shows the Establishment in Britain and the US at its very worst.

– MICHAEL CRICK

A truly shocking story of collusion, conspiracy and cover up at the heart of our financial establishment that have led to grave miscarriages of injustice. The book surely provides the basis for a renewed Parliamentary inquiry.

– JOHN MCDONNELL MP

It’s clear to me from the evidence that Mr Verity has unearthed that the committee’s inquiry into the Libor scandal was not told the whole truth: important pieces of evidence were with-held. The public rely on parliament to get to the truth. And this case illustrates why parliament must give itself greater powers or authority to require it. Parliament has been misled and must not let it rest.

– LORD TYRIE

The book has strong evidence that central banks not only knew about this rigging, they encouraged it.

– EVENING STANDARD

Rigged sets out in detail the role of the Bank of England and senior bankers in attempting to move bank rates down as they looked too high and were causing alarm in Westminster.

– PRIVATE EYE

For Izzy, Lucy, Cecily – and a better future.

And for my beloved stepfather, Will, who taught me the powerful role of the irrational in politics.

First published 2023

This paperback edition published 2024

FLINT is an imprint of The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.flintbooks.co.uk

© Andy Verity 2023, 2024

The right of Andy Verity to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9397 3

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Author’s Note

Preface

1 Lowball

2 Instructions to Lie

3 The Secret Orchestra

4 Collusion

5 A Point to Prove

6 Lip Service

7 Confirmation Bias

8 A Tangled Web

9 Diamond Geezer

10 The Seriously Flawed Office

11 The Man Who Couldn’t Lie

12 The Ringmaster

13 The Sushi Conspiracy

14 Better Not Call Saul

15 The Price of Honesty

16 The Price of Dishonesty

17 Run!

Epilogue: Hope Over Experience

Notes

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to the whistleblowers who took a stand for honesty, only to find themselves punished, their lives ruined. To the traders and brokers, vilified in the media and wrongly prosecuted for doing their jobs, who overcame their understandable distrust and spoke to me. To those lawyers who fought for logic and sanity. To all the people, some of whom I have never met, who took risks to leak documents and audio recordings in the hope that the truth would come out so that justice might prevail.

Thanks to Sarah Tighe for not letting the bullies get away with it, whoever they might be. To Jonathan Russell for putting me on to the most ghastly, astonishing story I have ever come across. To the source who made ‘Project Righteous’ happen (you know who you are). To Peter Page for his boundless enthusiasm, skill and encouragement. To the journalists of BBC Panorama and The Times for seeing that something lay beneath and upholding our country’s great tradition of investigative journalism as a democratic force. To Sarah Bowen for her brilliant work on The Lowball Tapes.

Thanks to my dearest mum Mary Rosalind, sister Tara and Canadian siblings Pete and Sarah. And to my wonderful and gifted wife Natasha for her steadfast love, humour and support.

AUTHOR’S NOTE

The conversations and exchanges of messages recounted in this book tell a story that the authorities on both sides of the Atlantic have known about for more than a decade but have chosen to keep quiet. Quotes are not recreated but taken directly from audio recordings and transcripts of the actual words spoken at the time in phone calls, recorded as a matter of routine on banks’ trading floors, and from contemporaneous emails and messages. They have been shared with more than a dozen regulators and investigative agencies around the world as well as with banks’ legal departments – but not with the public. Much of this is exclusive material and most of the information contained in it had never been reported.

These audio recordings and documents not only cast serious doubt on the prosecutions of traders and brokers for ‘rigging’ interest rates, they also contain evidence of illegal activity at the top of the financial system that has never been called to account – a secret history to which the public would otherwise have had no access. The true story they reveal would have been left untold had I not obtained crucial material on a flash drive, sent to me anonymously after I began writing and broadcasting about the scandal. Some of the audio recordings were broadcast in the 2022 BBC Radio 4 investigative podcast series The Lowball Tapes. The material has been thoroughly authenticated by cross-referencing it with public sources, including regulators’ notices and court materials.

Editorial note:

The dialogue has been edited for relevance, clarity and for the purposes of storytelling. Where the dialogue is unclear, the spelling or grammar has in some cases been edited or tidied up. Where material has been omitted, this has been indicated through the use of bracketed ellipses.

PREFACE

As a BBC reporter, I’ve spent the last twenty years reporting financial scandals and investigating financial crimes. I’ve confronted Ukrainian gangsters over their secret investments (google my name and you’ll soon come across video footage of a corrupt politician’s goon kicking me in the balls for my trouble) and investigated money laundering on an industrial scale in the Middle East. But in terms of sheer jaw-dropping, mind-boggling corruption, greed and injustice, nothing comes close to what’s revealed in these pages.

This investigation has been a rollercoaster ride like no other I’ve ever been on. Just when I thought I knew all its twists and turns, I was presented with a cache of thousands of hours of recordings of bankers’ phone calls, made during the financial crisis, and I was whipped upside down at 100mph through a hall of distorted mirrors until I didn’t know what was true, or who the good and bad guys were anymore.

Rigged starts by unveiling one extraordinary story: the big banks illegally rigging interest rates during the financial crisis that began in 2007, in the full knowledge – and sometimes with the encouragement – of Bank of England and Federal Reserve Bank of New York officials, along with several other financial institutions. Enough material for any book, you would think, but then comes the twist (which everyone, me included, missed at the time), morphing the story into something far more disturbing.

When the UK’s Serious Fraud Office (SFO) and the USA’s Department of Justice (DOJ) opened their criminal investigations into interest rate-rigging, the press reported that, at last, some of those bankers at the rotten heart of the financial crisis were going to jail. I imagine that people would have paid to sit on the juries that got the chance to find these junior bankers guilty on all counts. Indeed, the rate-rigging trials took place in a political context of justified public anger towards the banks, for all the lasting damage that their mismanagement had done to economies around the world, and therefore to the prosperity of millions upon millions of families.

As this book will show, those bankers were always innocent of the crimes with which they were charged. Even more astonishingly, when they committed the alleged foul deeds, they weren’t crimes at all.

Yes, you read that right.

The thirty-seven bankers whom the USA or UK have prosecuted since the financial crisis are innocent.

Nineteen of them were convicted, with one trader receiving a fourteen-year sentence (reduced to eleven years on appeal).

But why, you ask, should we care about some high-paid bankers going to jail? They’re all crooks, aren’t they? It’s a great question with an unsettling answer. The bankers who went to jail were the ones who put their faith in the justice system and told the truth. Even more incredibly, some were the very people who had brought the authorities’ attention to the crimes in the first place. They were whistleblowers.

Suppose you witnessed something criminal at work. If you worked in medicine, for example, and you saw a doctor abusing patients. Or in construction, and you knew your boss was using illegal materials that were cheap but highly inflammable. Or for the police, and you saw a senior officer planting evidence on an innocent person. Or for the media, and your editor ordered reporters to hack a phone illegally to get a story. You’d want to speak up, wouldn’t you? You wouldn’t want to carry that knowledge around with you for the rest of your life, knowing you did nothing. You’d like to think that if you reported any of these crimes, you would be protected.

Imagine instead that you found yourself under investigation, then arrested and your family’s future threatened. Then you were put on trial for something you didn’t do, for a crime that didn’t even exist and, several years later, were sentenced to years in prison, just for doing the right thing.

That is what happened to the traders who spoke up. Thousands of people in the banking world knew there was something rotten about the rate-rigging trials but did nothing. Because they knew if they did, then their livelihoods – and perhaps their freedom – would be in danger. This also means that they’re unlikely to speak out the next time. And there will be a next time.

Shattered by the experience of injustice, the prosecuted traders, including those who stayed out of jail, have suffered nervous breakdowns. The real perpetrators – not just of the real rate-rigging scandal but of the whole financial crisis – escaped with their multi-million-pound bonuses and giant pension funds intact.

The trials of junior bankers accused of rate-rigging were about sending out a message: bankers were being locked up. There is justice. Nothing more to see here, move along folks, it’s OK to start borrowing again. Of course, there is much, much more to see. Rigged uncovers the shocking truth behind the rate-rigging scandal, thanks to years of investigation, thousands of hours of recorded phone calls, emails between traders, bank executives and politicians, interviews and trial transcripts. It’s a chilling tale, jaw-dropping in its immensity. Because as it turns out, it’s not just interest rates that can be rigged – it’s the entire system.

1

LOWBALL

‘Peter Johnson?’

‘Hey Peter, it’s Ryan.’

‘Hello, Ryan.’

‘Hey man, uh—’

‘This is so fucking sick. It’s so, so fucking wrong.’

‘Should be higher?’

‘Much, much higher.’

‘Really.’

‘Much, much higher. Believe me, you’ve got no idea how much higher.’

‘Wow.’

(Barclays traders Ryan Reich, 25, in New York and Peter Johnson, 52, in London

29 November 2007)

Barclays cash trader Peter Johnson returned from a three-week family holiday at the end of August 2007 to find the world’s financial system on the verge of meltdown. The 5,000 workers streaming towards the gleaming thirty-three-storey, million-square-foot Barclays headquarters in Canary Wharf that morning had plenty to worry about. French bank BNP Paribas (the eighth largest in the world) had announced that it had frozen three of its hedge funds because they’d put billions of dollars in investments linked to defaulting mortgages in the USA that might never be repaid. There were rumours that British banks – Northern Rock in particular – were similarly exposed and fast running out of cash. No bank was willing to lend to any other bank for fear that they might go bust. The global credit crunch, the biggest financial disaster since the Great Depression of the 1930s, was officially under way.

Johnson, a greying 52-year-old smoker with a gravelly voice, had been with Barclays since 1981. Known to everyone at work as PJ, he had an unusually strong sense of right and wrong, and liked to speak his mind in forceful language, no matter who was listening. It was his job to borrow billions at a time and lend it on to departments within Barclays that needed cash, making sure the money flowing out of the bank in loans and investments was matched by money coming in. He’d seen his fair share of financial crises over the course of his career, so, putting rumours to one side, he got on with the business at hand.

Checking the ever-changing streams of data on the computer screens gathered in a crescent around his desk, PJ spotted something amiss: Barclays’ Libor rate was far too low.

What the Dow Jones or the FTSE 100 is to share prices, Libor (London Interbank Offered Rate, pronounced Lie-bor) is to interest rates: an index, updated every day, that tracks what banks are paying to borrow cash from each other. For the past thirty-five years, the repayments on millions of consumer loans and mortgages have depended not on the official interest rates you hear about on the news, set by central banks like the Federal Reserve or the Bank of England. Instead, they go up or down with the real cost to banks of getting hold of cash on the international money markets. Libor keeps track of that cost by showing the average interest rate banks are paying to borrow funds.

Every morning, PJ had a chore to do – a chore he’d been carrying out for two decades. He was the bank’s ‘Libor submitter’ for US dollars. That meant he had to submit an estimate, to at least two decimal places, of what interest rate he thought Barclays would have to pay to borrow a large lump of cash – in dollars – from the other banks just before 11 a.m. that day. He might put in, say, 3.43%. His counterparts at the fifteen other Libor-setting banks would each do the same thing; for example, Citigroup might estimate 3.41%, Lloyds 3.42%, and so on. Their estimates, known as ‘submissions’, would be ranked, high to low, and made public. The top four and bottom four submissions were struck out and an average taken of the middle eight to get the official London Interbank Offered Rate. Banks like Barclays had billions of dollars in loans, investments and trades linked to the Libor average, so they could make or lose money if Libor rose or fell. A tiny movement might sometimes make or lose the bank a million dollars.

Of course, PJ couldn’t just submit any old rate. It had to be realistic, based on the interest rates his bank was really paying, or could pay, to borrow funds that morning. If there was more than one offer to lend in the market that Barclays might take up, those offers wouldn’t be at exactly the same rate. Chase London might offer 3.41%, HSBC Hong Kong slightly higher at 3.43%, Bank of China Beijing 3.42% and so on. PJ could realistically borrow at the highest interest rate, or the lowest, or somewhere in the middle. That gave him a narrow range of accurate rates to choose from as his Libor estimate: up or down by no more than a hundredth of a percentage point or two.

Libors were calculated in ten currencies from US dollars to sterling to yen, and PJ could see that the Libor submissions in all currencies that morning were way out. There was no way anyone was offering cash at the cheap rates the banks were posting. He prided himself on setting an honest rate and, after studying the latest market data, corrected Barclays’ dollar number upwards by 0.15%.

This simple action – an attempt at honesty – set off a chain of events that would end up exposing the financial and judicial systems’ rotten heart, wrecking PJ’s life (among many others) in the process.

That morning, however, PJ had no idea of the consequences of his actions. After setting Barclays’ dollar Libor, he checked and rechecked the data for every other bank. He could hardly believe what he was seeing. All the banks were ‘lowballing’ – pretending it was much cheaper to borrow cash than it really was. The banks, almost devoid of cash and with no one prepared to lend to them, were lying through gritted teeth to prevent anyone realising how desperate they were. They were pretending they could get cash at the same cheap interest rate that other banks were putting in as their Libor estimate. But then they were going into the market to borrow funds at a much higher rate.

It proved the rates were false. If the cheap rates they were saying they could borrow at were accurate, why would they pay more? PJ called a colleague to vent: ‘I think these Libors are all fucked.’ He then emailed his boss, Mark Dearlove, head of liquidity management, a more polite assessment, finishing with: ‘Draw your own conclusions about why people are going for unrealistically low Libors.’

Dearlove came from a wealthy establishment family. His uncle was Sir Richard Dearlove, the former head of MI6. PJ had known Mark since the 1990s, when he’d been introduced as the new managing director of the cash desk where PJ worked. Dearlove was thirteen years PJ’s junior and on a gilded career path to the top of the bank, but PJ was pleasantly surprised to discover that didn’t mean he’d be pulling rank. He’d always taken time to listen, and they’d struck up a close working relationship over the years. When it had been a stressful day on the trading floor, they’d frequently blow off steam together after work as the alcohol flowed freely, and the younger boss relied heavily upon the benefit of PJ’s experience, especially during the financial crisis.

A concerned Dearlove forwarded PJ’s email to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York1 (the New York Fed, the USA’s equivalent of the Bank of England). He received no reply. PJ then received a call from Thomson Reuters. This was the financial information service to which he sent his Libor number. Reuters gathered all the numbers into a tidy report and sent it on to the Bank of England, the British Bankers’ Association (BBA, at the time the administrators of Libor and a trade organisation that represented 200 banks), along with other financial institutions. Reuters wanted to know why Barclays’ Libor was so much higher than everyone else’s. Was PJ sure it should be that high? He told Reuters he was absolutely sure. The other banks were putting in their Libor estimates way too low. His was the most honest rate.

PJ then copied several colleagues into an email: ‘Have a look at the range of Libors set by contributor banks. Needless to say I think I am correct and UBS at 5.10 is obviously smoking something fairly powerful.’ He told another colleague on the phone: ‘Some of the Libors that people have been putting in have been an absolute disgrace […] I’m leading the campaign to get Libors more realistic […] I think they’re doing it to try to persuade themselves that if they keep on putting in low Libors they might get some money, but it doesn’t work that way.’ On the phone to another trader: ‘It’s just such bollocks […] it’s absolute rubbish […] I mean you cannot get money there.’ Followed by another email: ‘Fun and games in Libor land where the popular premise seems to be that Barclays must be in trouble because it is setting its Libors so high. But other Libor contributors will almost certainly be setting their Libors lower than where they are paying […] As you can see there is something wrong in the State of Denmark and it certainly is not my Libors.’

What was wrong, of course, was that most banks, like Northern Rock, were fast running out of cash. No one was prepared to lend them money for more than a few days, for fear that they might have lost so much money on bad US mortgages that they wouldn’t even exist in a month. The only way they could get money was if they paid significantly higher interest rates. But they weren’t ready to admit what they would really have to pay to get the funds they needed. PJ’s campaign soon got the attention of the media. Bloomberg journalist Mark Gilbert called Barclays to ask if its higher Libor meant it was in trouble. Bob Diamond, at this time Barclays’ president and chief executive of its investment bank division, Barclays Capital,2 was unnerved enough by Gilbert’s call to email his concerns to his fellow directors.

Diamond, labelled the ‘unacceptable face of banking’ by an MP appalled by a Barclays Capital tax dodge, was widely regarded within the financial world as ‘the future of banking’ (indeed, he would go on to take the top job at Barclays, group chief executive, in 2011). The Bostonian, one of nine siblings and the son of a headmaster, had, true to the American stereotype, rubbed the Brits up the wrong way as he brought the immense profits of global investment banking to a Barclays that had, until his arrival, been struggling to make traditional banking pay.

‘Tucker [Paul Tucker, then Bank of England’s executive director for markets] said we were above the market on Libor,’ Diamond wrote in an email to senior executives, ‘and Bloomberg are looking at this story […] this could be the next leg in silly/bad press, can we get on it? AAAAAAARRRRRRGGGGHHHH!!!’

Barclays had already been receiving unwanted press attention for its recent reliance on the Bank of England’s ‘discount window’: a lending facility which provided funds to banks so tied up in the ebb and flow of myriad financial products that they had ‘liquidity issues’ – meaning a shortage of cash that day.

One of the people copied in on Diamond’s email was Jerry del Missier, then president of Barclays Capital. A clever, dark-haired French Canadian described by one colleague as ‘boringly competent’, del Missier had spent ten years working in Barclays’ investment banking division, making the bank more money than anyone else in the early 2000s, becoming one of the highest-paid bankers in London.3 He replied: ‘The whole Libor curve is rubbish. The real story is that these are all fantasy rates. Nobody is lending anything at the rates they are posting.’

The next day, del Missier received a call from Paul Tucker. In recent days, Tucker’s attention had been brought to Barclays’ share price: it was tanking. He was already engaged in the battle to save Northern Rock, having arrived at Threadneedle Street early that morning, marching quickly through the ornate, high-ceilinged lobbies and corridors of the Bank of England’s headquarters.

The rumour-mongers had been right. Northern Rock had been caught with its trousers down right in the middle of the US mortgage mess. The debt-ridden bank’s business model had relied upon it being able to borrow money from other banks and investors on a daily basis, but no one was lending, so it was down to the Bank of England to save it. Tucker, who had joined his beloved Bank of England immediately after graduating from Cambridge in 1980, needed to find £3 billion in emergency funding just to keep the Rock afloat for a few days or so.

Staring at the front page of the Financial Times as he drank his coffee, ‘Anxious Market Catches Barclays Short of £1.6 billion’, Tucker’s alarm was growing. It was the worst headline about a bank in living memory. He knew that Barclays had borrowed huge sums and that it had sacked a senior banker who’d tried to raise the alert over the vast amount of US mortgage investments it had accumulated, investments that no one now wanted to buy. And now, with these above-the-market Libor rates, it looked like Barclays was ‘bidding up’ the market – paying more than other banks because it was desperate for cash. Tucker feared that the true weak state of Barclays’ finances was now being exposed. No one would want to keep lending to a bank that was in some kind of distress and which might then struggle to borrow the funds it needed to keep going; and that could mean another Northern Rock on his hands – but much bigger. If it continued … The failure of one of the UK’s biggest banks was unimaginable, a total catastrophe; millions of customers panicking, a run on the bank, with no access to their money, even for a few hours could lead to a loss of confidence in the entire banking system – and that could lead to a depression. It didn’t bear thinking about.

Tucker knew that Libor was still way too low to reflect what banks were really paying to borrow cash. It had been set at 5.20% the previous morning, but the market data suggested that it should have been about 5.55%. A difference of 0.35% might not seem like much, but if you were a bank that had made loans of $50 billion, it could cost you $17.5 million (£13 million) every month. Lowballing was dishonest – and arguably downright criminal. Because smaller US and European banks lent trillions of dollars in loans linked to the Libor rate, the interest they collected was now lower than it should have been – much less than what they would have to pay to get hold of dollars on international money markets. With less money coming in than going out, they were losing millions of dollars every day.

Tucker also knew that the Libor rates that banks put in normally moved by just one or two hundredths of a percentage point per day (0.01–0.02%, known in the City as 1 or 2 ‘basis points’). A leap of 35 basis points would have caused total panic.

As it was, PJ, in an effort to ease Barclays’ dollar Libor up to where it should be, had gone as far as to correct it to 5.35%. It made no impact on the published Libor rate because it was among the top four excluded from the average. Other traders on the market, however, could see that Barclays’ Libor estimate was way higher than any other bank. An increase of 0.15 percentage points in Barclays’ dollar Libor appeared to signal that it was in trouble – Northern Rock kind of trouble. On Friday 31 August, they were even talking about it on national radio news programmes: was Barclays struggling to get hold of the funds it needed to keep going?

Barclays executives kept telling the Bank of England that PJ’s higher Libor rates were the accurate ones; it was the rest of the market that was wrong. True as that might be, it didn’t help Tucker to manage the situation. Speculation was growing that Barclays would imminently run out of cash. Early the next day, Saturday 1 September, Tucker emailed Jerry del Missier asking him to call him over the weekend. Del Missier forwarded it to Bob Diamond, who bounced it back: he guessed it was about Libor and decided Jerry was the best person to handle it. Later that day, del Missier picked up the phone to Tucker, who told him he was concerned about Barclays’ Libor submissions; they didn’t always need to be that high. It was the first of many such conversations, not only with del Missier but with Mark Dearlove and Bob Diamond, where Paul Tucker would ask why Barclays’ Libor rates were higher than other banks. Del Missier at first responded by defending the rates they’d put in. Barclays’ cash traders (PJ and others) were calling it where they saw it; it was costing more to borrow cash, so they were putting in higher Libor rates to reflect that. But for Tucker, that still wasn’t good enough.

Years later, in 2011, when del Missier was interviewed by the US Department of Justice, he was asked what Paul Tucker had told him that day. His reply was unequivocal: ‘That we should get our Libor rates down.’ That evidence, revealing that the Bank of England began instructing Barclays to post inaccurately low Libor rates in September 2007, was kept out of the subsequent UK trials of traders for rigging rates.4 Yet it revealed a much bigger manipulation of Libor by the Bank of England than any that the prosecution alleged against the traders.

After the weekend phone call with Tucker, del Missier called Miles Storey. A Barclays career man from the north of England, Storey already knew that the bank’s Libor rates were way off. He was the bank’s head of group balance sheet management, which in August 2007 was a bit like being head of tidal management for King Canute. Cash was flowing out of Barclays with alarming speed, threatening to leave a multi-billion-pound hole in the bank’s finances. Aged 43 and slim with straight dark hair, Storey was always immaculately dressed and carefully calculated what he said, to the point where he’d developed an awkward conversational habit of asking himself a question out loud and then answering it. Discussing PJ’s correction with a colleague he said, ‘Any Libor is, I shouldn’t really say this, but almost fiction […] Why are credit departments saying don’t lend to any bank […] over one month? Because we don’t know whether that bank will be there in one month. That could be the only reason.’

Immediately after del Missier hung up, passing on the fact that the Bank of England wanted them to lowball, Storey called Mark Dearlove. Both of them knew PJ was planning to set a higher Libor again to make it more accurate. He wanted to raise his estimate of the cost of borrowing cash by 10 basis points to get closer to the real interest rates on the markets where dollars were changing hands. After the instructions from above, that was looking awkward. ‘What I would like us to do is set exactly the same today as we did Friday,’ Storey told Dearlove. ‘That’s what we’ve agreed to do.’

Twenty minutes later, PJ was finishing a phone call with a colleague, telling him, ‘It pisses me off that we’re the only people being honest about this, and we are getting pilloried for it,’ before someone yelled at him that Storey was on the other line.

Storey trod carefully. ‘I […] will […] in no way try to get you to change your Libors. However, if you were comfortable in not raising them, again […] from a purely presentational point of view that would be good.’

PJ sounded uncertain as he replied. ‘Riiight, oookay.’

‘It would help if we sort of took the market with us rather than leading the market,’ Storey continued, ‘just from the external presentational point of view and all the hassle that the bigwigs get. And, to be blunt with you, the press that we’ve had […] So that, i-if you can still … in good conscience, not raise them or not raise them as much as you’re saying.’

The next day PJ kept his Libor at the top of the pack but refrained from raising it any higher. ‘I’d like to set it higher,’ he said in a phone call to a colleague, ‘but at the moment there’s a little bit of political pressure on me not to go any higher than I am at the moment. Like internal political, like big – big boys like Jerry. Jerry wanted me to set them lower today. I refused.’

PJ wasn’t the only Libor setter worried about the rates being set. Peter Spence, his equivalent for sterling Libor, said in a call to PJ: ‘I just want to adhere to the rules and every other bank is breaking ’em. I might be wrong, I mean, you know, don’t get me wrong: the higher Libor goes, I’m losing money like everybody else. But, I mean, sod it if you don’t tell the truth. The worst I find is we’re getting slated for everything that’s going on […] but I think in the end we’ll be vindicated.’

PJ agreed. ‘This Libor is an absolute fucking farce, you know,’ he told another colleague. ‘I mean it should be so much higher, but you’ve got all these arseholes like Citibank, sort of pushing out charts saying that Barclays’ Libors are too high – they must be in trouble. But I know I’m going too low. It’s ridiculous!’

Frustrated at being forced to lie, PJ kept trying to post higher, more accurate rates as his estimate of the cost of borrowing dollars. But the pressure from above to post false, low ones kept coming. At just after 8 a.m. on 19 November, PJ told Pete Spence what he’d just heard from Mark Dearlove. ‘Mark had a talk with Jon Stone [Barclays’ then group treasurer] on the phone, saying, “Oh what are you doing with Libors? You know, you’re going above the market again.” And he said, “Well that’s where they are, in fact they’re probably not high enough.” [Stone said:] “Ah, but you know every time […] that happens, if there’s any risk to our reputation, I’ve got to go to the board and explain it.” Mark said, “Well, I’ll go to the board and explain it if you want …”’

Later that day, PJ emailed Dearlove: ‘Just had a call from Miles [Storey] asking me to keep my Libors within the group (pressure from above).’ He gave in to the pressure, setting it within the middle of the pack. Two days later a jubilant Jonathan Stone called Mark Dearlove. Stone had been keeping a close eye on Libor because it was his responsibility to make sure the bank could raise funds as cheaply as possible.

‘Credit Suisse is now the outlier,’ Dearlove said.

‘Good … Isn’t it nice not to be the person, Mark?’ said Stone. ‘We’ve begged him for it […] Miles did say you were at the top end of the range. But provided you’re not the highest, I don’t mind.’

‘Yeah, they’re tempering it exactly right.’

‘Y’know, you’ve heard Bob [Diamond] as well,’ said Stone. ‘We don’t want to be in the press, it just ain’t worth it.’

PJ’s bosses were all too aware of the views of Diamond and other executives on the Barclays board. If PJ told the truth about the interest rates he was really paying to borrow dollars, Barclays would stand out too much from the ‘pack’ of lowballing banks. And that might attract press speculation just like it did in September that they were paying more because they were desperate to get hold of funds. Dearlove and Storey weren’t the ones ultimately telling PJ to lie. They were only the messengers carrying out an edict from senior management: stay out of the press. The pressure on PJ to lie was coming from the top of the bank.

By 29 November, PJ was posting Libors so far out from reality he was embarrassed. That morning the cheapest offer in the market to lend dollars over one month was at 5.60%. The other banks were clearly lowballing, telling brokers they were putting in submissions claiming that they could borrow dollars at anything from 5.15% (Royal Bank of Scotland) to 5.30% (Bank of Scotland) – 30 to 45 points below reality. They were already paying more than that to borrow cash – proving they were lying. Just in case that wasn’t bad enough, the Financial Services Authority (FSA, the UK’s financial regulator, since renamed the Financial Conduct Authority) had started to take an interest, warning one of the money brokers that arranged borrowing and lending between the banks, Tullett Prebon, of their obligation to show ‘fair and reflective prices’ about Libor on their screens. This was becoming impossible; how could they do the right thing? Dearlove set up an emergency conference call with Jonathan Stone and Miles Storey. PJ and his colleague on the cash desk, Colin Bermingham, joined the call.

‘Okay, so the dilemma we have,’ Dearlove told Stone, ‘is that we think 1-month Libor should be 5.50 […] Now if you put 5.50, we’re going to be 20 basis [points above every other bank] … It’s going to cause a shitstorm.’

Stone got it. If you put your head too far above the parapet, it might get shot off.

‘So, what I propose as a halfway house is, er – PJ you can shout me down; he’s already pulling faces at me – if you go with […] Bank of Scotland’s levels. But we kinda need to have a meeting to figure out what we’re going to publish […] tomorrow and I think we need to get a bigger audience involved in this. Jon, I understand the sensitivities and I think we need to take it upstairs.’

‘I’m with Chris [Lucas] and meeting Patrick [Clackson] at 12 anyway so […] if I can, off the back of that, maybe find five minutes to catch him.’

They discussed why other banks were lowballing. Their fear, Storey said, was, ‘If we let the Libors go up and up and up, we’ll all appear like we’re in a problematic situation.’

‘We are,’ interjected PJ.

‘No, I know – I know. I agree it’s kidding themselves,’ Storey came back. ‘And I appreciate that you, PJ, have been pragmatic in your approach throughout this. I think if we can stick – as Jon and Mark have said – stick with “at the high end along the lines of HBOS” [Halifax Bank of Scotland] … for today.’

‘OK, Miles.’ PJ had no choice. He had made it clear he wanted to put in a rate for borrowing dollars over one month at 5.50%. His bosses had overruled him and instructed him to go 20 points lower.

Dearlove, Stone and Storey knew that, in effect, they had just instructed PJ to post false Libor rates that morning – to lowball. But Dearlove was most worried about the next day’s Libor fix. The last day of November was important because it was when some banks and investment funds worked out the value of their assets and liabilities, including investments and loans that were linked to Libor. That meant their assets would be revalued – making or losing money based on that day’s Libor average, also known as the ‘fix’. If it were false, that would mean a false market, based on a false, lowballed Libor. Stone said he was already about to meet the Barclays group finance director Chris Lucas, who sat on the board of directors of Barclays, in the office of Patrick Clackson, then chief financial officer of Barclays Capital. Before the conference call finished, Storey agreed to contact the BBA to try and get them to do something (see page 57). Later that day, Stone spoke to Chris Lucas and asked him what he wanted him to tell the cash traders about Libor. Lucas told him he would prefer that they stay where they were the next day (rather than go higher as PJ thought they should). Stone passed the message down to Dearlove.

As PJ sat down at his desk the next morning, he glanced at the window on his screen listing yesterday’s false Libor submissions, including his. He asked the money brokers who were on the end of permanent, open phone lines to his desk: what were the other banks going to put in as their Libors? Once again, he learned, they were all going to lowball, pretending they’d pay far less than they’d really pay. Enough of this game.

‘Hello Miles, it’s Johnson here.’

‘Hello Johnson, it’s Miles.’

PJ was proposing to post a more accurate Libor: 5.40. Storey cleared his throat. ‘Have you had a chance to talk to Mark? […] Just one sec, Pete, hold on one sec mate.’

PJ could barely make out Storey’s voice speaking to someone on another phone, explaining that banks were still paying far more to borrow dollars than they were admitting in their publicly stated Libor rates. He was trying to find out what Barclays’ top bosses wanted to do. ‘So the guidance is stick within the bounds? […] So no head above the parapet, no partial bleeding, etcetera? Okay.’

Storey returned to PJ’s line. ‘Did you overhear any of that?’

‘Er, not really …’ PJ’s tone was wary.

‘Right. Mr Lucas doesn’t want us to be outside the top end.’

‘Jesus Christ,’ PJ said, exhaling. Then, sounding slightly incredulous, reluctantly agreeing: ‘Alright, so … OK.’

‘And apparently they chatted [about this] on the whole of the thirty-first floor, by the way,’ Storey added. PJ knew what that meant: the thirty-first floor of Barclays group headquarters at 1 Churchill Place, Canary Wharf, where Bob Diamond, Chris Lucas and group chief executive John Varley had their offices.

Soon after the renewed instruction from the top of his bank, PJ, still filled with frustration, picked up a call from a young derivatives trader named Ryan Reich at the US headquarters of Barclays in New York. Aged 25, shaven-headed and physically fit from a youth spent playing sports, Ryan came from a wealthy East Coast family and had been hired just over a year before to trade financial products that went up or down in value depending on movements in the dollar Libor rate. Energetic and eager to succeed, it was part of Ryan’s job to call PJ in London at least once a week and ask if he could tweak his Libor settings up or down by a hundredth of a percentage point or two to help the trading positions of the New York desk he worked for. Neither of them saw anything wrong with that. So long as PJ put in interest rates at which the bank could realistically borrow, he was simply choosing a rate from the narrow range of offers to lend in the market which Barclays could take up. But this lowballing they’d been seeing for the last three months was something else altogether.

‘Hey Peter, it’s Ryan.’

‘Hello Ryan … This is so fucking sick,’ PJ told him.

‘Why?’ Ryan suppressed a laugh.

‘It’s so, so fucking wrong.’

Ryan knew he was talking about Libor. ‘Should be higher?’

‘Much, much higher.’

‘Really.’

‘Much, much higher. Believe me, you’ve got no idea how much higher.’

‘Wow.’

‘I mean the only reason I went 30 in one month [5.30%5 – PJ’s Libor estimate of the interest rate he’d pay to borrow dollars for a month] was because that’s the highest that anyone else was gonna go and I didn’t want to be seen to be an outsider. I wanted to go 50 [5.50%] … It’s just ridiculous […] The best offer of cash is at 60 [5.60%] [...] If you pay [to borrow euros] and swap them back into dollars, you’re paying 5.70.’

‘Wow.’

‘You sort of get the drift. People are setting these so ridiculously low, it’s just getting to be a laugh. And I’m actually quite worried that there’s some kind of reputational risk here for any bank which sets them this low,’ PJ said. ‘You look at some of the people – these arseholes. Right, you’ve got Deutsche – set at 5.18. Well, we all know he’s in the shit […] WestLB set at 5.22: he’s in the shit. Royal Bank of Scotland 5.18. Well, if Royal Bank of Scotland are setting at 5.18, why is ABN [Amro], who I believe they took over, paying 5.40? So that’s one to think about. Citibank – he’s in the shit – he set at 5.18 […] and UBS, in the shit, 5.16. So you tell me whether those Libors are right? They’re wrong. They are so fucking wrong. And unfortunately, unless I’m given the green light to go ahead and put rates where I think they are, I don’t think I can have any influence.’

A week later, feeling very emotional, PJ again vented to Ryan. Since the crisis began, he’d been writing short pieces circulated within Barclays to anyone who wanted to read them, explaining why he was right to be setting higher Libor rates and other banks were wrong to be lowballing. He’d openly said he was leading a campaign to make Libors more honest. But now he kept getting instructions from the top, via Storey or Dearlove, forbidding him from being any more truthful than the other banks. That day, Barclays had borrowed $600 million from Citibank at an interest rate of 5.40%. Yet because of the pressure from above, PJ couldn’t post his Libor rate where he was paying. ‘I actually feel embarrassed that I set my 1-month Libor at 5.30 and I was paying 5.40 in the market,’ he told Ryan. ‘I’m 4 over the next highest contributor and nearly 5 over the average.’

‘You get shit for that, don’t you?’ asked Ryan.

‘Well; people just think I look like an absolute prat.’ PJ’s indignation was growing. ‘What worries me is it’s getting – I think it’s getting down to a sort of ethical and legal thing now.’

‘Yeah, you mentioned that to me last time.’

‘I’m patently giving a false rate!’

Unable to stand much more, PJ again told his boss that banks were posting rates far lower than they were really paying in the market – including Barclays. ‘I’ve set 1-month at 30 [5.30%]. It’s a load of bollocks […] I’m paying 40 [5.40%]. WestLB Dusseldorf, in fact, is paying 50 and […] will probably set at 25, so that’ll be an interesting one.’

‘It’s outrageous, isn’t it,’ Dearlove said.

‘Yeah, I mean it really is just sick […] I tried to get in touch with Jon Stone but he wasn’t there – cos I really do feel people must think we’re bloody stupid […] I think we should take a stand.’

‘You know I agree with you. I – I’ve represented your views very strongly.’

‘I’m going to write you an email, and then you can do with it what you want,’ said PJ.

‘Okay, fair enough! You’re right because I want to get, um, something written from the guys upstairs.’

‘So I’ll just write a thing – I’ll just say I think it’s bringing the Libor market into disrepute, Barclays into disrepute, me into disrepute. That’s what I really object to.’

Dearlove knew how forceful PJ’s language could be. ‘Make sure you do it in a way I can forward it.’

‘Don’t worry, I’ll be as sweet as I possibly can.’

In his email PJ wrote: ‘I am feeling increasingly uncomfortable about the way in which USD libors are being set by the contributor banks, Barclays included […] Barclays set at 5.30% (4 bps over the next highest contributor and nearly 5 bps over the actual Libor). At the same time that we were setting at 5.30%, I was paying 5.40% in the market […] My worry is that we are being seen to be contributing patently false rates. We are therefore being dishonest by definition and are at risk of damaging our reputation in the market and with the regulators. Can we discuss urgently please?’

Aware that pressure to lowball came from the very top of the bank, from Barclays’ board of directors, Dearlove called Stone the next day at 7.49 a.m.

‘I’ve actually had an official email now from Peter Johnson, who’s basically saying, look, I want something in writing now because I think, um, you know, that this is all wrong.’

‘Well, have you talked to Jerry del Missier about it?’ Stone asked.

‘Well, he’s – he’s in Nepal.’

‘Oh, for fuck’s sake.’

‘So I don’t, I don’t quite know who to escalate it within BarCap [Barclays Capital, the bank’s investment bank division] […] I guess the best person I can think of is Rich Ricci and Bob.’

‘I think Bob understands it,’ said Stone. ‘And the answer is up until now … it’s like guys this is just … continue to push further.’

Dearlove wanted Barclays to be setting a good example, rather than just following the low standards of every other lowballing bank. ‘The fact of the matter is, that we’re not setting Libors where we should be,’ he told Stone. ‘We’re at the top of the range so we’re not affecting the Libor settings because we’re, we are being excluded anyway because we’re too high […] But on the other side I can understand the board’s perspective, but what frustrates me a-above all, uh, is that the board seems very concerned, and I think that these guys should be on the front foot rather than the back foot.’

‘Listen, they haven’t had a conversation about it for the last, you know, the last two weeks,’ said Stone.

Dearlove knew the board was already familiar with the Libor problem. But he was concerned it might become a bigger issue and urged Stone to raise it again with them. Stone suggested he should speak to Rich Ricci, Bob Diamond’s aptly named lieutenant from Nebraska who loved to spend the tens of millions of pounds of share awards he collected on racehorses, flamboyant suits and showy hats. A friend and ally of Diamond’s since the mid-1990s, Ricci was chief operating officer of Barclays Capital, running it alongside Jerry del Missier.

Stone said he’d speak to Chris Lucas, the finance director who sat on the Barclays group board. Just under an hour later, Stone called Dearlove back. ‘I caught up with Chris and at the moment he’s still much in the same camp as well,’ said Stone, ‘I know what you say about being on the front foot and I don’t think he sees the benefit we achieve from that. I think he too, like myself, said, “Well, what does Bob think on the issue?” […] I just don’t want to find out, you know, that you and I make a decision, and everyone says, “You’ve gone barking mad, guys.”’

There Dearlove was, trying to get the board of Barclays to do the right thing. Yet the board didn’t ‘see the benefit’. As his own frustration grew, he circulated PJ’s email to Barclays’ top bosses and called the compliance director, Stephen Morse: ‘I’ve been liaising with Jon Stone every day about our settings. We’ve been telling him we want to be putting high rates in. He has been told by the thirty-first floor that we can be the highest, but we must not be a standout person because they’re worried we’re at the stress point,’ Dearlove told Morse. ‘I’ve just had a conversation with the Stone man [Jonathan Stone] this morning and I have asked him to go back to the thirty-first floor, so he went back to Chris Lucas this morning and said, look, you know this is wrong. And I was at a meeting yesterday with the ECB [European Central Bank] with a whole lot of other banks and all the banks were saying – this is just bullshit – but people said, “Your settings are the most realistic because they’re the highest.”

‘I’m actually going to see Rich Ricci about it because Jerry is away at the moment,’ Dearlove said. ‘I need to try and get some advice from somebody as to what I’m supposed to do. Cos I don’t think – I can no longer make that decision. I don’t think it’s fair on PJ to be setting something which he knows is wrong.’

‘I agree,’ said Morse.

‘I actually got an email from PJ, which I will forward to you. Because he wants something in writing – cover your arse, whatever you want to call it. And I agree with him.’

Dearlove had a meeting with Morse and Rich Ricci at lunchtime, where Ricci said he’d call Lucas but believed they needed to go to the FSA and talk to them explicitly about their problem.

The next morning, Morse phoned the FSA, located in Canary Wharf in London’s Docklands area, a stone’s throw from Barclays’ headquarters. He spoke to Mark Wharton, who led the team at the regulator that supervised Barclays and knew Ricci, Lucas and Diamond. Barclays had kept the FSA informed in September when PJ tried to submit a higher, more accurate rate, the media misreported the reasons and the share price tumbled. Since then, Morse explained, they’d been justifiably reluctant to go higher, too far above the rest of the pack. The FSA was familiar with this as an issue. Morse gave some examples of banks submitting one low rate, and then paying another higher one in the market. Could that be regarded as manipulation or market abuse?

Wharton had been involved in drawing up the regulator’s Code of Market Conduct years before, when they’d looked at the issue and concluded Libor couldn’t be manipulated by one bank alone. You’d need at least four banks colluding together to shift the average artificially. The FSA didn’t regulate Libor, he told Morse. If rates were inaccurate, Barclays should go to the BBA.

Later that day, Morse sent an email reporting the phone call to senior managers including Chris Lucas, Jerry del Missier, Rich Ricci, Jonathan Stone and Barclays’ top lawyer and general counsel, Mark Harding. ‘Mark [Wharton] seemed grateful for the “heads up”,’ Morse wrote. ‘He informed me that he would escalate this to an appropriate level within the FSA and will get back to me ASAP with any planned response. In the meantime, Mark agreed that the approach we’ve been adopting seems sensible in the circumstances, so I suggest we maintain status quo for now.’ The email was forwarded to Dearlove, who sent it on to PJ. To him, the ‘status quo’ meant he was allowed to put his head above the parapet, so he was the highest of the ‘pack’ of banks submitting their estimates of the cost of borrowing cash, but not too far away from the next one down. Now the FSA knew all about it and they weren’t complaining. The FSA seemed to be OK with the approach Barclays had been taking.

Morse hadn’t quite told the FSA that PJ’s view of where Libor should be had been overruled by the bank’s top bosses. But after Wharton escalated the issue within the FSA, no one raised the alert or reported it to the police. To Barclays executives and lawyers, the FSA had been told about the understated, inaccurate Libor submissions that had been going on for months now, later to become known as ‘lowballing’. And the regulator wasn’t troubled by it. When, years later, the FSA and the US regulators began to fine banks hundreds of millions of pounds for rigging interest rates, that awkward fact wouldn’t feature in their press releases.

In his one-man campaign for honesty, PJ sometimes felt quite alone. He seemed to be the only one in the City of London or Wall Street who cared about this industry-wide fraud, ordered from the top, that he’d been pressured, against his protests, to take part in. As the crisis intensified in the months to come, he would resolutely keep up his campaign, undeterred by any premonition of the high price he, personally, would come to pay. Neither he nor Ryan Reich could have guessed how closely their fates would be intertwined, or how the fraud now visible to them on a screen of false figures would morph into a financial and political firestorm that would leave them, and dozens like them, badly burned.

2

INSTRUCTIONS TO LIE

Week after week, month after month, as the banks muddled their way through the credit crunch, PJ was pressured to keep his Libor low, and week after week, month after month, PJ resisted as much as he dared and set Barclays’ dollar Libor at the top of the pack. Then, in the autumn of 2008, the crisis reached a new pitch of intensity. When Lehman Brothers collapsed on 15 September, it became impossible for any bank to pretend it was business as usual.

From his corner of the trading floor on the second floor of Barclays Capital’s headquarters at 5 North Colonnade, Canary Wharf, PJ watched in mounting alarm as news about the worsening crisis streamed in to the eight large computer monitors above his desk. Every day, there was a shock headline of the sort you’d normally see only once a year. On 16 September, a once-mighty investment bank sunk by losses on US mortgages, Merrill Lynch, announced it was selling itself to Bank of America. Then one of the biggest insurers in the world, AIG, which had underwritten vast amounts of insurance against US mortgages defaulting and couldn’t afford to pay the huge claims that were now being made, was bailed out by the US government at a cost of $80 billion. Then on the morning of 17 September, the biggest mortgage bank in the UK, Halifax Bank of Scotland (HBOS), stricken by bad loans it had made, which prompted a relentless battering of its share price, was taken over by a rival bank, Lloyds TSB.