20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

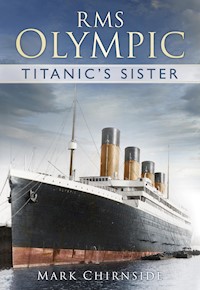

Launched as the pride of British shipbuilding and the largest vessel in the world, Olympic was more than 40 per cent larger than her nearest rivals: almost 900ft long and the first ship to exceed 40,000 tons. She was built for comfort rather than speed and equipped with an array of facilities, including Turkish and electric baths (one of the first ships to have them), a swimming pool, gymnasium, squash court, á la carte restaurant, large first-class staterooms and plush public rooms. Surviving from 1911 until 1935, she was a firm favourite with the travelling public – carrying hundreds of thousands of fare-paying passengers – and retained a style and opulence even into her twilight years. During the First World War, she carried more troops than any other comparable steamship and was the only passenger liner ever to sink an enemy submarine by ramming it. Overshadowed frequently by her sister ships Titanic and Britannic, Olympic's history deserves more attention than it has received. She was evolutionary in design rather than revolutionary, but marked an ambition for the White Star Line to dominate the North Atlantic express route. Rivals immediately began trying to match her in size and luxury. The optimism that led to her conception was rewarded, whereas her doomed sisters never fulfilled their creators' dreams. This revised and expanded edition of the critically acclaimed RMS Olympic: Titanic's Sister uses new images and further original research to tell the story of this remarkable ship 80 years after her career ended.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

To my inspirational grandparents, Anne and Alfred Huntand Joan and Stuart Chirnside

Acknowledgements

It would have been impossible to complete this work without the generous, kind and comprehensive help from a great number of wonderful people and institutions. It is important that people – each person with their own specialised knowledge – come together and share their knowledge, to form a comprehensive history. It is difficult to express my sincere thanks and gratitude in words, yet I know my thanks is heartfelt. I would like to thank the following people for generously sharing knowledge, helping me with material, offering interpretations, and advice. Thanks are also due for those who kindly granted permission for me to quote from copyright material:

Scott Andrews; Mark Baber; Raymond Bealing; George Behe; Bruce Beveridge; Randy Bigham; Charles Dragonette; Shelley Dziedzic; Robert Grove; Josh Gulch; Joe Hartwell; Brian Hawley; Nigel Hampson; Philip Hind; Pine Hodges; Brent Holt; David Hudson; Ellen Mackay; Sheila Jemima and Jill Neale; John Johnstone; Stuart Kelly; Daniel Klistorner; Peter Kohler; Ray Lepien; Henning Pfeifer; Bill Sauder; Inger Sheil; Bill Smy; Michael Standart; Eric Takakjian; Kevin R. Tam; Brian Ticehurst; Jason D. Tiller; Dr. Joan Unwin; Pat Winsip; Andrew Williams.

I would also like to thank the following institutions and people for all their assistance: The staff of the Cunard Archives, Sydney Jones Library, Liverpool University; The Imperial War Museum; Public Records Office, Kew, London; the help of the staff of the Maritime Collection, Southampton Reference Library; Gregory Plunges of the National Archives and Records Administration-Northeast Region (New York City); The Cutlers’ Company, The Cutlers’ Hall, Sheffield; The Canadian War Museum; Louise Higgs (The Halifax Herald Ltd.); The Canadian Letters and Images Project, Department of History at Malaspina University College. Karen Kamuda and everyone at the Titanic Historical Society; Mrs. J. M. Kenyon, for permission to quote from the diaries of J.R. Tozer, and the trustees of the Imperial War Museum; Antoinette L. Fitzsimons for her kind permission to quote from Colonel Leprohon’s diaries.

My grateful thanks to Campbell McCutcheon, and everybody at Tempus Publishing. This book would not have come into being without them.

In undertaking such a project, there is always a danger of simply repeating what has been said in the past. Indeed several people expressed to me the hope that this project would not do that; I trust their hope is justified. There is always new information to be found, no matter what the subject. Once people start believing otherwise, history becomes irrelevant. An enormous number of details have been, and no doubt are still being, overlooked. And the obligatory note about source conflict: it can be difficult at times to portray events accurately. Gaps and inconsistencies abound even in primary sources. Sadly there are other gaps due to the misfortune of some records over the years. A number of records of the United States Coast Guard relating to the Nantucket Lightship were destroyed in a warehouse fire in the 1950s or ’60s, robbing the researcher of that information. Few White Star records survive prior to the 1934 merger, although the surviving archive includes the 1931 and 1932 balance sheets, General Manager Committee Meetings of 1929 to 1931, and passenger records for that period. There are more.

I encourage anyone with any corrections, or further information and memories, to contact me so that any errors can be corrected, and our collective knowledge increased. I know David Gray would also love to hear information about Olympic’s wartime career, to complement his excellent research. As a closing sentence, I would like to emphasise that all errors and mistakes are mine alone, and reiterate my thanks to the many kind people who have helped with this project. Your kindness is astonishing and I am very grateful to you all.

Mark Chirnside, August 2004

Acknowledgements to theSecond Edition

It goes without saying that I continue to owe a debt of gratitude to everyone who helped with the first edition of this book. I am very grateful for the encouragement of my parents, family and friends, and all the support they gave me.

I have learned a great deal from correspondence and discussion with numerous individuals since the original book was published. In many cases, people have shared information which has been referenced specifically in the endnotes. At other times, information obtained for other projects or for my own general interest nonetheless proved useful in revising the first edition. Further thanks are due to the following people, who gave so generously of their time and expertise by sharing information, discussing evidence, sharing photographs and plans, and offering encouragement:

Scott Andrews, George Behe, Bruce Beveridge, Jenalin Burdette, Myles Chantler, Pavel Chlupac; Christian Cody, Ed Coughlan, Ray Cowell; John Creamer, Ralph Currell, Neil Egginton; David Hume Elkington; Tad Fitch; Ioannis Georgiou, Steve Hall, Sam Halpern, Sean Hankins; Brian Hawley, Remco Hillen, Ken Hillier; Brent Holt, David Hutchings, Stuart Kelly; Daniel Klistorner, J. Kent Layton, Ray Lepien; Oliver Loerscher, Michael Lowrey, Stuart Lythgoe; Olivier Mendez; Craig Mestach; Peter Mitchell; Mike Poirier, Trevor Powell, Bob Read, Inger Sheil, Jonathan Smith; Nick Thearle, Hilary Thomas; Rich Turnwald; John D. (‘Jack’) Wetton; Russ Willoughby.

A number of people and organisations have helped with both my ongoing research in general and some specific enquiries for the purpose of this project: the staff of the Cranbrook Archives; Cunard Archives, University of Liverpool Library; English Heritage; Getty images; IMarEST; Imperial War Museum; Library and Archives Canada; Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division; London Metropolitan Archives (accessing Guildhall Library Manuscripts Section); National Archives (formerly the Public Records Office); National Maritime Museum; National Museums Northern Ireland; Public Records Office (Northern Ireland); Southampton Reference Library; TopFoto; Tyne & Wear Archives Service; United States Coast Guard Historian’s Office. I also owe my sincere apologies to anyone who may have been inadvertently missed out, or those I have not been able to contact.

Finally, my thanks to everyone involved in the mammoth tasks of the original book’s completion and the preparation of this new edition, in particular Amy Rigg, Commissioning Editor, Juanita Zoë Hall, Managing Editor and all at The History Press.

Mark Chirnside, March 2015

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements to the Second Edition

Author’s Introduction to the Second Edition

Introduction

The Tale of Two Sisters:

Lusitania

and

Mauretania

A New Dawn

‘Queen of the Seas’

‘Passenger Accommodation of Unrivalled Extent’

‘Unrivalled Magnificence’

The

Hawke

Collision

Calamity and Mutiny

New Beginning

The

Audacious

Incident

Wartime: ‘Old Reliable’

‘The Great

Olympic

’

‘The Film Star Liner’

Old Veterans

‘Looking Like New’

The Nantucket Affair

Twilight

Cruising, a Floating French Hotel and a Summer Lay-up

End of the Line

Epilogue

Appendix I: Chief Engineer Bell’s Report

Appendix II: Maiden Voyage Mysteries

Appendix III: Cunard’s Spy

Appendix IV: ‘The Millionaire’s Special’

Appendix V: Back in Favour

Appendix VI: HMT

Olympic

: Wartime Voyage Chronology (1915–19)

Appendix VII: The First and the Last

Appendix VIII:

Olympic

Passenger Statistics 1911–35

Appendix IX: The ‘Big Three’:

Homeric

,

Olympic

and

Majestic

Passenger Statistics 1920–36

Appendix X:

Olympic

Specification File

Appendix XI:

Olympic

: From Profit to Loss 1931–33

Appendix XII:

Olympic

Captains

Bibliography

Plates

Copyright

Author’s Introduction to theSecond Edition

Although many of the events in this book took place more than one hundred years ago, Olympic’s history is still evolving. Researchers continue to unearth new information or documentation that improves our understanding, changes perspectives or adds to our knowledge of the ship and her life. The continuing analysis only improves our comprehension.

The original book’s goal was to draw attention to Olympic in her own right, rather than as the sister ship of one of the most famous ships in the world. To a large extent, it succeeded, and it won considerable praise. However, it was largely written fourteen years ago and appeared in print in 2004. Building on original research, it introduced a lot of new or previously little-known material, from small anecdotes to more substantial information: J. Bruce Ismay’s request to Cunard for working drawings of some Mauretania windows that would be suitable for Olympic, which sheds light on the degree of mutual co-operation that existed between the rival companies; Chief Engineer Bell’s report of the maiden voyage; detailed information about Cunard’s research into Olympic, based on designer assessments of her public rooms and interiors; an engineering viewpoint of her machinery and overall layout; and the notes Cunard’s naval architect, Leonard Peskett, made when he travelled on board in August 1911, which provided an interesting insight to life at sea on Olympic during her first summer season. Anecdotes, extracts from diaries during peacetime, as well as previously unpublished accounts of life on board during the war, all combined to shed new light on her career. Data of Olympic’s passenger carryings over the years, provided with generous assistance from other researchers, helped to illustrate the context in which she succeeded, and then the inevitable decline when new competitors and the Great Depression took their toll in the 1930s. Detailed accounts of the Hawke collision, the sinking of the U103, the Fort St George and Nantucket Lightship collisions all included new information or facts that were not widely known, even to the modern day exploration of the sunken lightship, for the first time in a single volume.

Now, the second edition is intended to add to our knowledge with the addition of other material and more rare illustrations. Much of it could only have been provided through the kind-hearted generosity of other researchers. In particular, the chapter covering the Hawke collision has been expanded, with additional testimony about the accident and information about the appeals that followed; rare photographs have been added covering the mutiny in 1912, and an interesting account of being at sea aboard Olympic just after the Titanic disaster; further information about the attempts to attack and sink the ship during her war service; new details about her post-war refit and service in the 1920s; the voyage of Ivan Poderjay in 1933, a man suspected of murdering his wife and disposing of her body through a porthole; more information about the events that led to the Cunard and White Star merger and the cancellation of her cruise programme and schedule for 1935-36, which led to the ship’s retirement. New appendices include an explanation that there was an error in the maiden voyage crossing time reported in 1911, which led to the ship’s speed being understated; an analysis of the contribution first, second and third class made to revenues and profits; the recovery of her popularity after the Titanic disaster; a detailed chronology of the ship’s war service; a more detailed breakdown of passenger carryings over her career; new data comparing Olympic and her post-war running mates; a comparison tracking the fall from profit to loss in the early 1930s; and a detailed list of the ship’s commanders over her career. Altogether, the original book has been expanded from 320 pages with a 16-page colour section to 352 pages with a 16-page colour section, or a total increase from 336 to 368 pages.

When an article or book is published, its contents represent an understanding of those historical events at that particular moment in time. Historical discoveries are ongoing. Since the original book’s completion, I have had the pleasure of working with other researchers, and relatives of passengers or crew who generously shared information and photographs. This new edition of RMS Olympic: Titanic’s Sister takes advantage of the progress from the intervening decade and hopes to convey an even more accurate and complete picture of Olympic’s life and times, eighty years after she was withdrawn from service.

Introduction

O lympic and Titanic began life as yard numbers 400 and 401 respectively, at Harland & Wolff in Belfast. Their original plans envisaged two ships that were practically identical, with Olympic’s keel laid three months ahead of her younger sister. They grew, together, until Olympic’s launch on 20 October 2010 and her sea trials at the end of May 1911. Titanic was launched on 31 May 1911, the same day Olympic left Belfast to begin her illustrious career spanning a quarter of a century. During construction, and over Olympic’s months of service in the summer of 1911 and early 1912, alterations and improvements were made to ensure Titanic was an even better vessel, but they remained largely identical.

Many liners have been labelled the ‘first modern ocean liner’ or ‘the first floating palace’, but Olympic has a strong claim for making much of that progress. She was substantially larger than her nearest rival, Cunard’s Mauretania, and the increase in her tonnage alone was greater than the entirety of the largest vessel afloat less than a generation earlier. The range of facilities on offer was unrivalled when she entered service. First-class passengers enjoyed a gymnasium, swimming pool and Turkish bath establishment – facilities expanded after they had been tried on the White Star liner Adriatic – alongside an indoor squash court and reception room where people could meet prior to dinner. An à la carte restaurant, the first on a British liner, liberated passengers from the set hours of the dining saloon and gave them a greater choice of dishes. All these innovations became de rigueur on board the liners that followed, and were accompanied by the usual range of public rooms: veranda cafés, a smoke room, lounge and reading room. Although conservative in a number of ways – Olympic did not sport a double-height domed dining saloon or some of the soaring ceilings of public rooms on board some other vessels of the period – her interiors were impressive. The main first-class staircase, with its overhead dome and ornate clock (‘Honour and Glory, Crowning Time’), was perhaps one of the finest public spaces ever to go to sea. Her enormous size permitted vast expenses of deck and promenade space, while she carried fewer first-, second- and third-class passengers than she might have done, given her size. John Maxtone-Graham wrote that Olympic was the ‘last of the lean, yacht-like racers and the first “floating palace”’.

A fatal encounter with an iceberg during her maiden voyage ended Titanic’s career and the lives of two thirds of her passengers and crew. Today, Titanic is probably the most famous ship ever built; Olympic’s success has been less well recorded in history, even though she fulfilled her potential.

This volume is an attempt to go some way towards putting that right.

The Tale of Two Sisters:Lusitania and Mauretania

The early years of the twentieth century were marked by the rapid progress being made by the various shipping companies in the highly competitive North Atlantic trade. Although traditionally a British-dominated trade, by the turn of the century the Germans had made great progress and were making a serious challenge to both major British shipping lines, Cunard and White Star. Following the introduction of the 10,000-ton Teutonic and Majestic in 1889 and 1890, however, White Star had adopted a policy of aiming above all for the finest vessels afloat in terms of comfort, luxury and facilities, while leaving the pursuit of speed to Cunard. The Hamburg Amerika Linie followed White Star’s lead several years later, which left the competition for speed to Cunard and their German rival Norddeutscher Lloyd. Such competition led to the introduction of Norddeutscher Lloyd’s quartet of superliners – Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse (1897), Kronprinz Wilhelm (1901), Kaiser Wilhelm II (1903) and Kronprinzessin Cecilie (1906) – which captured the Blue Riband between 1897 and 1907 and gradually increased the speed from about 22.4 to 23.7 knots. In 1891 White Star’s Teutonic had wrested the prize for speed from the American Line’s City of Paris by reducing the westbound passage to 5 days 16 hours and 31 minutes at an average speed of some 20.5 knots, completing the eastbound passage in 5 days 21 hours and 3 minutes, but Cunard’s twin 12,950-ton Campania and Lucania of 1894 cut the times down to 5 days 7 hours and 23 minutes westbound and 5 days 8 hours and 38 minutes eastbound. Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse crossed to New York in 5 days 20 hours at an average of 22.4 knots in 1897, but three years later the Hamburg Amerika Linie’s Deutschland took the prize. Several German liners held westbound and eastbound records during the next few years, and in 1906 Norddeutscher Lloyd’s Kaiser Wilhelm II crossed in 5 days 8 hours and 16 minutes at an even higher average speed of some 23.7 knots. By 1914 the two major German lines had clearly overtaken the British competition in terms of tonnage: Hamburg Amerika owned 194 ships with an average tonnage of 6,739 tons, making a total of 1,307,411 tons; Norddeutscher Lloyd owned 135 ships of 6,726 tons, for a total of 907,996 tons; White Star owned thirty-three vessels of an average 14,330 tons, totalling 472,877 tons; and Cunard owned the smallest number of vessels, twenty-nine ships with an average tonnage of 11,871 tons, bringing their total tonnage up to 344,251 tons.

White Star – legally known as the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company – had finished the nineteenth century on a high note with the Oceanic; a magnificent ship bearing the same name as the company’s first express vessel of 1871, which was the largest in the world and had earned the title: ‘Ship of the Century’. Although designed for a similar speed to Teutonic, the White Star Line’s Blue Riband holder, Oceanic would not be able to capture the Blue Riband as the German vessels had improved on the necessary speed; however, this is not to say that she was a slow vessel, as she was less than 2 knots slower than the speed required for the Blue Riband. With a length of 685ft between perpendiculars, a total length of 705ft, Oceanic was the first vessel to exceed the length of the ill-fated Great Eastern (1858), and being 68ft 6in in breadth, 49ft depth and with a usual draught of 32ft 6in; her gross tonnage was 17,274 tons. Grandiose plans were made for another running mate for the ship, although tragic circumstances would force the cancellation of this vessel.

On 1 January 1891 J. Bruce Ismay – usually known as Bruce Ismay – and James Ismay became partners in Ismay, Imrie & Co., essentially the managers of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company; and their father, Thomas Henry Ismay, resigned from his managerial position but remained chairman, staying interested in the company.1 In fact, he had been very involved with the Oceanic project and had planned for her running mate to be named Olympic, but when Thomas Ismay died aged seventy-two on 23 November 1899 plans for the sister vessel were cancelled, and an even larger vessel, Celtic, was planned. Following his death, his two sons Bruce and James would manage the company with Thomas Ismay’s old colleagues, William Imrie and W.S. Graves.2

The White Star liner Oceanic, depicted at sea on a souvenir log abstract issued in 1910. She was a popular vessel, carrying around 1,000 passengers on each crossing during her early years of service. (Author’s collection)

Baltic, the third of the three sisters, had her own dedicated following. (Author’s collection)

Celtic would be the first of four large liners that came to be known as the ‘Big Four’ or ‘Celtic’ class, combining luxury, stability and comfort with economy of operation. Following the completion of the fourth liner, the class would together complete twenty-one years of profitable hard work, while the liners’ lives spanned thirty-three years, from 1901 to 1934. Their sizes ranged from Celtic’s 20,904grt to Adriatic’s 24,541grt. Adriatic (1907) had the first ever floating swimming pool and Turkish baths. Some 280 tons of coal per day were consumed by the boilers to drive the twin reciprocating engines for speeds of over 16 knots.3 With the completion of this class in 1907, the White Star Line’s express service to New York was well equipped with high-calibre vessels, as one reporter later noted:

The history of the line reads like a romance – one fortunately intimately associated with the progress and material prosperity of Belfast, where the whole of this noble fleet was built. The connection between the White Star Line and Messrs Harland & Wolff Limited dates back many years, and if, on the one hand, the company has obtained through that business intimacy the greatest ships in the world, on the other hand, the Lagan yard has gained prestige and fame from a policy that set at nought all previous conceptions regarding the size limit of vessels, and denied the pessimism of less far-sighted rivals …

The Adriatic, Oceanic, Majestic and Teutonic are mail and passenger steamers engaged in the Southampton and Cherbourg–Queenstown–New York service, calling at Plymouth on the eastern passage. The Baltic, Cedric, Celtic and Arabic are on the Liverpool–Queenstown–New York route. Other splendid vessels sail to and from Boston and New York and the Mediterranean …

Just prior to the completion of the Cedric, the White Star Line’s ownership had in fact changed, which would have a remarkable effect on the great company’s main rival, the Cunard Line. The Oceanic Steam Navigation Company Limited was itself a British-registered company with an all-paid-up capital of £750,000, controlled by three directors: Chairman J. Bruce Ismay; the Right Honourable Lord Pirrie, of Harland & Wolff; and Harold Sanderson. Following the change of ownership, eight shares were still held by Messrs E. Grenfell, Vivian Smith, W. Burns, James Gray, J. Bruce Ismay, Harold Sanderson, A. Kerr and Lord Pirrie, but the remainder were held from 1902 by the International Navigation Company Limited of Liverpool, which was also a British-registered company, with an all-paid-up capital of £700,000, controlled by four directors: chairman J. Bruce Ismay, Harold Sanderson, Charles Torrey and Henry Concanon. This company had controlling interests in a number of other shipping lines: the British and North Atlantic Steam Navigation Company Limited; the Mississippi and Dominion Steamship Company Limited; the Atlantic Transport Company Limited; and the Frederick Leyland Company Limited (the Leyland Line). Against these shareholdings, the International Navigation Company Limited had issued share lien certificates for an impressive £25,000,000; while the share and share lien certificates for the International Navigation Company Limited were owned by the International Mercantile Marine Company (IMM) of New Jersey, or ‘by trustees for the holders of its debenture bonds’. Thus, the complicated ownership structure of the White Star Line can be summed up as follows: Liverpool-based Ismay, Imrie & Co. were essentially the managers of the British Oceanic Steam Navigation Company, otherwise known as the White Star Line, which in turn was owned by the International Navigation Company Limited of Liverpool, that was owned by the American International Mercantile Marine Company (IMM) of New Jersey, one of American financier J.P. Morgan’s companies.

Morgan, a man of enormous wealth, saw an opportunity to reduce undue competition in the competitive North Atlantic trade, employ economies of scale and thereby generate considerable profits. By 1912 IMM owned 120 ships totalling 1,067,425 gross tons – approaching the size of Hamburg Amerika – with six more vessels under construction.4 However, the combine’s start had not been good in terms of its performance: merging the large number of lines into a streamlined organisation was not an easy task and initially some of the small lines had remained competing with each other on routes, directly in contradiction to IMM’s interests. J.P. Morgan realised that only J. Bruce Ismay was capable of improving IMM’s fortunes and, after some encouragement, in February 1904 Ismay became president of IMM, aged forty-four, remaining chairman of the White Star Line.5

Following IMM’s acquisition of the White Star Line, Cunard’s chairman, Lord Inverclyde, gained support from the British Government to change his company’s Articles of Association in order to prevent control by foreigners, but at the same time he had a radical proposal regarding a twenty-year low-interest £2,600,000 loan.6 If the Government were to grant the loan and an annual £150,000 subsidy, Cunard would construct two swift superliners to Admiralty specifications, re-establishing British Atlantic domination.7 Inverclyde’s proposal was appealing to the Government. Germany’s recent achievements had seen the loss of Britain’s long-term domination of the Atlantic, as Germany’s greatest shipping companies expanded, and the loss of the White Star Line to American J.P. Morgan was even more upsetting. The two proposed superliners would certainly be a good step to help restore the balance, while if they were constructed to Admiralty specifications and available in times of war, they would be a welcome addition to the Royal Navy, still the largest navy in the world. Parliament, led by Conservative Prime Minister Arthur Balfour’s Government, voted in favour of such a move.

Lusitania and Mauretania were launched a few months apart in 1906, entering service in September and November 1907 respectively. They soon proved themselves, as they engaged in a friendly rivalry to be the fastest liner in the world. Passenger carryings were strong and their grand passenger accommodation won numerous admirers, although Cunard did not opt to include the Turkish bath establishment, gym or ‘plunge’ pool, which Adriatic featured when she entered service a few months earlier.

Although both vessels were significantly larger than the Adriatic in gross tonnage, their actual weight (or displacement) was not much greater. Whereas the White Star liner’s propelling machinery needed to generate over 16,000 horsepower for a speed of about 16.5 knots, Cunard’s ships had engines that could produce more than four times as much power. The result was that their new liners had a top speed about 10 knots clear of Adriatic, making them the clear choice for passengers concerned with a speedy crossing.

Lord Pirrie had become the controlling chairman of Harland & Wolff following Sir Edward Harland’s death in 1895 and Gustav Wolff’s retirement in 1906. He directed an extensive programme of modernisation and expansion of his shipyard’s facilities between 1906 and 1908 in order to meet future requirements of the White Star Line for new vessels to compete with Cunard and the German lines. These were undertaken on a costly and magnificent scale. A reporter noted:

They involved the laying out of two berths large enough for vessels of such length and weight, and the erection of a gantry which is undoubtedly the largest in the world. Thus there has been added to Belfast’s gigantic achievements a structure massive and towering, almost time-defying in its strength, and one of the sights which arrest the engrossed attention of the traveller who visits the city for the first time. On its original site there were four berths, spanned by three large gantries. One slip was left where it was and the two other gantries were lifted up bodily onto rails and transported sideways until they covered this slip, which now has the use of all three. This cleared the way for the new slips for the leviathans. First of all a bed sufficiently strong to take their enormous weight had to be constructed. For this purpose the ground was heavily piled and then a concrete floor reaching in places 4ft 6in thick was laid on, and around the piles in such a manner that the latter take the load. The floor is suitably inclined to ensure a steady launch. The gantry already referred to was designed by the firm, and constructed by Messrs Sir William Arrol & Co. Ltd, the electric cranes being supplied by Messrs Stothert & Pitt. The space covered is more than 850ft long by 270ft broad, while the height is 180ft. No fewer than twenty-three crane hooks are fitted, and the motors total something like 1,500 horsepower … These cranes support the hydraulic riveting machines …

Mauretania, depicted on a card postmarked 22 June 1909. As the sender noted, she increased her average speed to almost 26 knots. (Restored Digital File © Eric K. Longo, 2012)

Harland & Wolff’s Queen’s Island works underwent significant modernisation before Olympic’s construction could begin. (Ioannis Georgiou collection)

An early illustration of Olympic appeared in the New York Times in March 1908. Her length was exaggerated, although she was significantly longer than her Cunard rival, and the profile of a three-funnel vessel showed a superstructure more in keeping with the ‘Big Four’. (Digital restoration by James Samwell, © 2011/New York Times)

Much could be – and as a matter of fact has been – written eulogising the wonderful prescience and foresight of such men as the late Sir Edward Harland and T.H. Ismay. The former saw the commercial utility of building large ships, while the latter falling in with the idea played his part in their utilisation in the great march of Inter-Oceanic … intercourse.

During the summer of 1907, Mr and Mrs J. Bruce Ismay dined one evening with Lord and Lady Pirrie at their London home, Downshire House, Belgrave Square. Ismay’s biographer, Wilton J. Oldham, described what followed:

Ismay and his host, who both believed in the ‘big ship’ with great comfort and moderate speed, first discussed the Olympic and Titanic, which were to be followed by a third [ship] …*

After dinner was over, they drew up rough plans of the three sisters. They were to be the last word in comfort and elegance, and although fast, the key word was to be safety and comfort for the passengers, combined with economy of operation.9

‘We would naturally try to get the best ship we possibly could,’ J. Bruce Ismay later said. ‘We wanted the best ship crossing the North Atlantic when we built her.’ He took quite an active role in the design of the new vessels.

In order to divert attention away from the Lusitania, one day before she arrived in New York after completing her maiden voyage, the first public press announcement was made regarding the new vessels and detailing the rough concept. It was reported that Harland & Wolff were working on a 1,000-foot design for ships ‘bigger than the Lusitania’. According to one source, the size would be in the region of 40,000 gross tons. Equipped with a possible combination of reciprocating and turbine engines, it was stated of the ship’s speed:

It is probable that her speed will be only 22 knots, the cost of every extra knot after 20 knots being so excessive that steamship companies are averse to such high speeds.

At the same time, there was a progress report in the New York Times of the Lusitania’s maiden voyage performance. She was not to perform as well as expected, failing to gain the Blue Riband. Her best day’s run so far had been 575 miles at an average of some 23.2 knots. Many were hoping that the ship could increase her speed to the estimated maximum of 25–26 knots.

Sure enough, Lusitania did better as she settled in and fulfilled the hopes invested in her. Several months later, in March 1908, J. Bruce Ismay made some comments to the New York Times about his own company’s plans. The paper quoted him speaking of two ships 1,000ft long, although the figure had no basis in reality. ‘This is the first time in its history that the White Star Line has been able to enter the field of ship construction without a handicap. Hitherto we have been restricted by the limitations of our former home terminal – that of Liverpool,’ Ismay noted, ‘… but now we have moved our terminal to Southampton, that restriction no longer exists, and so, for the first time, we are able to enter the field without any handicap of this nature, Southampton being a spacious harbour and its waters so wide and deep …’ He did not want to comment on the specific plans, beyond saying that the new ships’ accommodation would ‘be far ahead of anything that has yet been projected’.

The newspaper pondered, ‘Will these roomy new leviathans have trolleys or moving sidewalks to carry passengers up and down their far-reaching decks? Will they have theatres and shopping arcades? When the bow reaches port will it be necessary to telephone the fact to the other end?’ With an imaginative flair, the reporter noted, ‘If the rate of increase in steamship dimensions should be maintained for the next hundred years at the same ratio that they increased from 1807 to 1907 the ship launched at the end of the next century would have a speed of 6,527 knots a day, and would be able to cross from New York to England in about thirteen hours.’ It would be ‘nearly a mile’ long with accommodation for 33,000 passengers, but that was far in the future.10

Further information about the ‘new White Star ship project’ appeared on 16 April 1908, albeit with inaccuracies:

Olympic, 1,000-foot Liner.

White Star Line selects name for its leviathan – may build sister ship.

Liverpool, 16 April – The new 1,000-foot steamship, the construction of which is to be commenced later in the year for the White Star Line, will be named Olympic.

Harland & Wolff will build it and it will be designed expressly for the Southampton to New York trade.

It is possible that the White Star Line will decide to order two boats of this class instead of one.

Away from inaccurate press reports, Harland & Wolff were busy with the reality of designing the largest vessels that had yet been built. Lord Pirrie was involved in the practical design of the new ships, insofar as he considered their general dimensions and overall profile; general manager Alexander Carlisle was charged with ‘the details, the decorations, the equipments and the general arrangement’; Thomas Andrews was heavily involved in drawing up the plans and assumed Carlisle’s duties following his retirement on 30 June 1910; and Edward Wilding, Andrews’ deputy, worked in detail on the scientific side, dealing with questions such as the necessary strength and watertight subdivision.

Pirrie’s original three-funnelled concept was changed to a four-funnelled design, enhancing the fine lines of the ship and matching the four-funnelled Cunard and German vessels, which were equated with speed, size, strength and luxury. The initial design concept presented to the White Star Line directors on 29 July 1908 was labelled:

General Arrangement

S.S. No. 400

850ft x 92ft x 64ft 6in

Design ‘D’.11

It showed accommodation for 3,104 passengers – 600 in first class, 716 in second class and 1,788 in third class – and lavish accommodation. The first-class lounge, smoking room and dining saloon were all crowned by magnificent glass domes; there was a Veranda Café and a reading and writing room, extensive promenade areas and rather plain-looking stairwells. There were 598 seats in the first-class dining saloon, 580 in second class and 594 seats in third class. Servicing first class were two elevators, while an enormous swimming pool, gymnasium and Turkish bath area, the same size as the first-class dining saloon, was included.12 Many features would be modified or altered, but the basic design would remain roughly the same.

On 31 July 1908, the White Star Line signed a letter of agreement for construction to proceed. The shipbuilder would employ their usual ‘cost plus’ arrangement, whereby they would request payment for the materials and all related construction costs, before adding an additional percentage commission. The arrangement reflected the close relationship between the owner and builder, ensuring that the shipbuilder would make a profit. While there was undoubtedly an understanding that the builder would not spend excessively, there was no incentive for them to employ anything but the finest materials their design required.

In fact, the project involved a remarkable financial ambition. By September 1908, White Star’s fleet had expanded to twenty-three ships, with a gross tonnage of 311,403. They were valued at £4,850,000 but, by the time Olympic, Titanic and their third sister ship had been completed, the company would have spent more constructing them than the entire value of the existing fleet. Contrary to popular belief, neither J.P. Morgan nor IMM financed construction. The White Star Line borrowed an initial £1,250,000 in October 1908 and another £1,500,000 in July 1914, paying an interest rate of 4½ per cent and with the fleet as security. As the money was being borrowed commercially rather than with favourable government support, the interest rate was almost two-thirds greater than what Cunard were paying on the loan they had taken out for Lusitania and Mauretania, and the White Star ships would have to pay their way without an annual subsidy. However, White Star saw it as a necessary investment in their future. During the preceding ten years, White Star’s total net profit – £6,175,852 – added up to almost double that of Cunard. Profits were more than 50 per cent greater in 1907, and the company’s management intended to retain – and expand – their advantage.

A cutaway view of Olympic, intended to demonstrate her many decks, included views of the swimming pool, squash racquet court and gymnasium. The dome over the first-class dining saloon is not shown in this view published in June 1909. Originally intended to be on the same level as the swimming pool, as with Adriatic’s arrangement, the ship’s gymnasium was relocated subsequently from the port side of F-deck to the starboard side of the boat deck. Many other changes took place between the approval of the ‘Design “D”’ proposal in July 1908 and the ship’s completion, and it is interesting to note the lifeboat davits depicted on the boat deck. (Scientific American, 1909/Author’s collection)

Notes

* Although it is popularly believed that the two men first discussed their new ships in the summer of 1907, as Oldham reported, in fact the order for the first two was first recorded by Harland & Wolff on 30 April 1907. If the dinner took place the following summer, it was a discussion of something that was already being planned. (Perhaps, years later, Mrs. Ismay remembered the year as 1907 instead of 1906 when she assisted Wilton J. Oldham? See Gunter Bäbler’s article ‘The Dinner at Lord Pirrie’s in Summer 1907: Just a Legend?’ in Titanic Post, Swiss Titanic Society, 2000 for a more detailed discussion.)

1. Merchant Fleets, page 14.

2. Merchant Fleets, page 15.

3. Merchant Fleets, pages 55–59.

4. E & H TT, page 13.

5. E & H JJ, page 19.

6. Liners, page 42.

7. Mauretania, page 5.

8. Shipbuilder, page 18.

9. Ismay Line, pages 167–168.

10. Merchant Fleets, page 17.

11. Birth, endpapers.

12. Lynch, page 20.

A New Dawn

Construction of the ship initially labelled as ‘Yard Number 400 TSS Olympic, Harland & Wolff Limited, Queen’s Island Belfast’ began with the laying of her keel on 16 December 1908, as the shipyard’s 400th commission. It marked a new era in shipbuilding and marine engineering, for her sister vessel – ‘Yard Number 401 TSS Titanic’ – would be constructed by her side as she grew. Two such large vessels had never been constructed, let alone side-by-side, in the same shipyard at the same time. Of Harland & Wolff’s 14,000-strong workforce in 1911, between 3,000 and 4,000 men worked on the Olympic.1 Despite her unprecedented size, however, she would be constructed using traditional materials and methods, but in suitable quantities for such a great vessel.

The keel served as the ship’s ‘backbone’, located on the vessel’s centreline in the cellular double bottom. Mostly 5ft 3in deep, the double bottom’s depth was increased to 6ft 3in underneath the location of the main engine room and strengthened in that area to cope with the movement, and to a lesser extent, weight of the engines, being – unusually – carried up to the turn of the bilge for about half of the ship’s length. Divided into four transverse compartments, the double bottom had a total of forty-four watertight compartments, which were used for storing drinking and boiler water; any list taken by the ship could hopefully be corrected by the water distribution. In addition, if the ship ran aground the double bottom would hopefully prevent water entering the main body of the liner’s hull. Barely three months after construction began, on 10 March 1909, the double bottom was all bolted up and hydraulic riveting was well advanced. As an indication of the great number of rivets needed in the vessel, 500,000 rivets – weighing 270 tons – were used in the construction of the double bottom alone.2 By the use of hydraulic riveting throughout nearly the whole of the double bottom, including the bottom shell plating up to the turn of the bilge, maximum strength was ensured, as hydraulic riveting was considered the strongest method then available. The sheer of the bilge was not considered great in Olympic, the hull maintaining a more pencil-box shape, which gained the advantage of the ship being more resistant to rolling in a seaway. By contrast, the Mauretania’s bilge sheer was somewhat greater and she had earned a reputation of giving sometimes mischievous pitches and rolls. As a further method of preventing excessive rolling and improving the ship’s stability, two bilge keels 25in deep were installed for a length of 295ft along the bilge amidships on each side of the vessel.

The task of choosing Olympic’s propelling machinery would not be completed definitively until several months after construction began. While the piston-based quadruple-expansion reciprocating engines had been successful on previous liners such as Oceanic and the ‘Big Four’, on the other hand turbines had been a considerable success for Lusitania and Mauretania. As early as September 1907, suggestions had appeared publicly that the new liner would incorporate a combination model of reciprocating engines and a low pressure turbine. In March 1908, J. Bruce Ismay was reported as saying that this would be the case, and the design concept approved in July 1908 also depicted the combination. Harland & Wolff were reasonably confident of the advantages. By employing two triple-expansion reciprocating engines driving the two outer propellers, the steam exhausted into the low pressure turbine engine would enable it to drive a centre propeller. In effect, the low pressure turbine was the fourth stage of expansion, because it was able to make use of steam at a pressure lower than the reciprocating engines could make use of. However, it was not until two ships ordered for the Canadian service (which became Laurentic and Megantic) were completed that the results of a combination could be seen in practice.

They were largely identical sisters, with Laurentic employing the combination machinery to drive her three propellers and her sister the conventional reciprocating engines driving two propellers. Laurentic’s performance proved superior to her sister and, having demonstrated the concept on a smaller scale, the combination machinery could be used on a much larger scale for Olympic and her sister. The shipyard and engine works had been ordered to proceed with Olympic and Titanic ‘except with machinery’ on 17 September 1908; the engine works were told to proceed ‘with boilers’ on 26 February 1909; and instructions were issued to go ahead ‘with [the] remainder of machinery’ for Olympic on 20 April 1909: a mere five days after Laurentic had been delivered. An effective merger between Harland & Wolff and John Brown & Co., Clydebank, enabled the Belfast shipbuilder to gain access to the necessary technology, and work on the low pressure turbines would be subcontracted to Clydebank.

Constructed by the Darlington Forge Company, the liner’s stern frame weighed 70 tons, the two side-propeller brackets 731⁄4 tons and the two forward-propeller boss arms 45 tons, with a central aperture in the stern frame housing the central propeller. Mild cast steel was used for the stern frame, which was constructed in two pieces, connected using the finest Lowmoor iron rivets 2in in diameter and with a total weight of more than a ton. By the end of August 1909, the stern frame had been fitted to the ship; the fitting of the propeller brackets and boss arms followed. Manufactured by the same company, the vessel’s rudder was built of five sections of solid cast steel, coupled together with large bolts; it weighed 1011⁄4 tons, was 78ft 8in high and 15ft 3in wide. Of special interest, the rudder’s top section was forged from special ingot steel ‘of the same quality as naval gun jackets’.

Plans depicting Olympic and Titanic were printed in TheShipbuilder in 1911. Subsequent changes to both ships soon rendered them out of date. An inboard profile, showing the ship’s side and basic interior layout, is displayed above along with deck plans of the boat and promenade deck, A. Below, the deck plans show the bridge deck, B; shelter deck, C; saloon deck, D; upper deck, E; middle deck, F; lower deck, G; orlop deck, lower orlop deck; and tank top. (J & C McCutcheon collection)

At the opposite end of the ship, the stem was of rolled steel with a cast-steel forefoot which connected the stem solidly to the keel plate and bar. Provided at the top was a hawse pipe, through which a steel-wire hawser could be passed that held the central anchor; the central bower anchor weighed an impressive 15H tons, while the port and starboard anchors were to be roughly 8 tons each in weight, the cables needing to be a little over 3in in diameter and 330 fathoms long. However, while the central anchor was housed forward on the ship’s deck and the side anchors at the side in the hull plating, an anchor to my knowledge was never housed on the stem itself.

Olympic’s hull overall had a length of fractionally under 900ft, being 882ft 9in long from the foreside of the stem to the farthest end of the poop deck. However, as she was constructed with a traditional counter stern, whereby the poop and other decks were continued beyond the stern post, forming an elegant overhang, her ‘length between perpendiculars’ as it was called was somewhat less than her overall length. Indeed, her length between perpendiculars was 852ft 6in, measured from the foreside of the stem to the after side of the stern post; in a very technical measurement, her ‘length at quarter depth from the top of weather deck to the bottom of keel’ was 849ft 2in. On the ship’s plans the length between perpendiculars, measured from the after side of the stern post to where the stem met the upper deck, was shown as exactly 850ft 11⁄2in, whereas on most other ship plans this was measured from the aft stern frame to the forward load waterline. The hull itself had a maximum breadth amidships of 92ft 6in, although the higher portions of the superstructure, that is, deck A and above, had a width of 94ft in order to achieve more space.

Framing of the main body of the hull followed after the construction of the double bottom; Olympic’s hull frames numbered 305, extending 66ft above the level of the bilge to the bridge deck and spaced an impressive average of only 2ft 91⁄2in apart. Unlike on some vessels, where the frames were numbered from bow to stern, Olympic’s were numbered from amidships; frames were numbered from ‘1 to 148 aft’ and ‘1 to 157 forward’. Generally, the frames were spaced 36in apart amidships, gradually narrowing in steps to 24in at the bow and 27in at the stern. This way additional strength was achieved in these areas where it was needed, more than compensating for the narrow hull plating at bow and stern. The vessel’s frames were spaced thus:

Frames

Spacing

157 to 134 forward

24in

134 to 119 forward

27in

119 to 107 forward

30in

107 to 95 forward

33in

95 to 0 forward

36in

0 to 111 aft

36in

111 to 121 aft

33in

121 to 133 aft

30in

133 to 148 aft

27in

Describing the frames, one newspaper stated, ‘They are of channel section, 10in deep amidships, and of angle and reverse bars at the ends. At frequent intervals there are heavy web frames. Increased strength is ensured at the machinery spaces by the web-frames being placed at closer intervals. Specially heavy bracket plates connect the frames with the wing brackets.’

‘As framing proceeded the transverse beams were fitted in place on each deck level,’ one technical report stated at the time. ‘These beams are made of channels 10in deep, up to the lower deck, and of smaller section above this: all are placed, of course, to suit the spacing of the frames, to which they are connected by efficient brackets. There are four longitudinal girders in the width of the hull extending for the whole length of the ship. These are built up of plates with deep angles at top and bottom … This general description of the structure indicates the great strength of the hull, the aim being to ensure the maximum of stiffness in a heavy seaway.’ Framing of the hull was finished by 20 November 1909.

On 6 November 1909, the Southampton Times outlined the vision of Olympic’s hull, growing into an enormous entity:

As the structure rises, one cannot fail to be impressed with the wonderful effect achieved by the manipulation of the various materials in the hands of the constructors of what is already a mighty fabric in the making.

It is clear that Southampton as well as Belfast was proudly awaiting the new liner’s launching and completion, and in a patriotic fashion the reporter waxed lyrical:

The genius of man has created out of ordinary materials a powerful instrument of progress and development. In many ways the ship is the greatest of all national assets, for in a world consisting of about three-fourths water and one-fourth land, it is probable that the greatest nation will always be the one whose command of the sea and whose maritime interests are the most extensive.

Siemens-Martin steel was used throughout the ship’s shell plating and upper works. It had been used on the previous generation of express liners, Teutonic and Majestic, whose hulls remained in excellent condition. Considered ‘battleship quality’, it was a high-quality steel ideal for conventional hand-driven and hydraulic riveting.3 Although it was not the practice of the White Star Line to have their ships classed by Lloyd’s, the steel employed was tested to the classification society’s satisfaction. Throughout most of the hull, the outer shell plating consisted of plates 30ft long and 6ft wide. It was an inch thick amidships, narrowing towards the bow and stern where the hull frames were spaced closer together. Where necessary, the hull plating was doubled along the turn of the bilge and the side of the uppermost decks (the sheer strake) amidships – in some locations the structure was several inches thick – and the plating that formed the deck itself was also thickened. Generally speaking, it was the central three-fifths of the hull that would be subjected to the highest stresses, and by massing material throughout these areas the hull was imbued with ample strength. As well as doubling the plating, hydraulic riveting was also used amidships to a greater extent than on previous vessels, to further increase the ship’s strength. While it could be employed amidships, where the plating was straight and easily accessible, towards the narrower, angled confines of the bow and stern hand riveters were employed.

In June 1909, the Scientific American sought to demonstrate Olympic’s great size by comparing her to earlier ships. (Scientific American, 1909/Author’s collection)

On top of the hull itself sat the superstructure, consisting of the deckhouses on B, A and the boat decks. While it was strong enough to withstand the hostile North Atlantic, the superstructure did not contribute any strength to the ship. It simply sat atop of the structural hull and was largely independent of it. As a result, it was divided into three sections by two expansion joints – essentially gaps in the superstructure – which enabled it to flex in a seaway. They protected the superstructure from forces which it, unlike the structural hull, was not designed or intended to endure. The hull itself was entirely plated by 15 April 1910.

Dividing the machinery spaces and cargo holds situated underneath the ship’s accommodation areas were watertight bulkheads that also separated the main body of the hull into distinct compartments; the stiffeners of the bulkheads were 50 per cent beyond Lloyd’s requirements in terms of their strength, being ‘considerably in excess’ of Edward Harland’s 1891 bulkhead committee’s recommendation, while the plating was between 10 and 20 per cent thicker than Lloyd’s requirements. The design of the ship’s watertight subdivision was such that it enabled her to remain afloat and stable with any two watertight compartments flooded: even the two largest. It is not widely appreciated that she would also remain afloat with any three compartments flooded, with a few exceptions; and, in some scenarios, with even more – such as the first four compartments from the bow. Harland & Wolff did not employ longitudinal watertight bulkheads (extending along the length of the ship), or watertight decks, and for good reason. The shipbuilder was concerned that longitudinal watertight bulkheads could cause a ship to list severely, because they would contain the flooding to one side of the ship; similarly, the danger with watertight decks was that if flooding occurred above them, leaving air pockets below, it would wreak havoc with the ship’s stability. What might be useful in one situation might prove fatal in another. (In fact, longitudinal bulkheads employed on Teutonic and Majestic were subsequently pierced because they came to be regarded as dangerous.) By employing transverse bulkheads, running across the ship from one side to the other, these dangers were avoided, while giving what seemed to be an ample margin of safety. The design was so sound in this regard that it met or exceeded standards in force more than a century later.

In order for Olympic to achieve a service speed of 21 knots it was necessary for her engines to develop 46,000hp, but additional power was provided to ensure that she could maintain this speed through the bad weather conditions frequently found on the Atlantic.

Inside the largest engine room that had then been built into a ship, two four-storey-high four-crankshaft triple-expansion reciprocating engines were housed. Each with a high-pressure 54in-diameter cylinder, low-pressure 97in cylinder, intermediate 84in cylinder and a fourth 97in cylinder, the engines took steam from the boilers at a pressure of 215psi. While running at 75rpm it was expected that each engine would develop some 15,000hp.

Situated aft of the main engine room was the turbine engine room, which housed a low-pressure 420-ton Parsons’ turbine, taking the exhaust steam from the main engines at a pressure of 9psi. While the main engines were running at 75rpm, the turbine would run at 165rpm, indicating some 16,000hp.

Developing sufficient steam for the engines was no easy task. Twenty-four 15ft 9in diameter double-ended boilers 20ft in length were provided and five single-ended 11ft 9in boilers. Housed in six boiler rooms with a total length of 264ft, the five single-ended auxiliary boilers were housed immediately forward of the main engine room in boiler room 1, boiler rooms 2 to 5 housing five double-ended boilers each and boiler room 6 only housing four double-ended boilers because the hull began to narrow at that point towards the bow. The total heating surface came to an amazing 144, 142sq.ft, 159 furnaces being provided, six per double-ended boiler and three per single-ended boiler. All twenty-four ‘main’ double-ended boilers could provide ample steam for the service speed on their own, without even using the auxiliary boilers.

Fitted on each side of the watertight bulkheads that separated the vessel’s boiler rooms were transverse coal bunkers 30ft in height, ‘conceived with a view to minimising the amount of handling of the coal for each boiler’. As the bunkers were arranged on each side of the watertight bulkheads, coal was available practically from the bunker doors next to the boilers. Another advantage was that the ship could be coaled from either side of the pier.

It is incredible that the propellers themselves had a total weight of 98 tons, the wing propellers weighing 38 tons each and the central turbine-driven propeller 22 tons. The wing propellers were 23ft 6in in diameter, with three bronze blades bolted to a steel bossing; and the central propeller was 16ft 6in diameter, having four blades and entirely moulded in manganese bronze. Fittingly, the wing propellers remain the largest ever fitted on any liner, driven by the largest reciprocating steam engines ever constructed. Propellers, engines and boilers would all be installed on the ship following the launching, which by April 1910 – when the hull plating was complete – was set to take place six months later.

It was intended that Olympic would be able to maintain ‘an average service speed of 21 knots’ in all weather conditions, with plenty of power in reserve enabling her to overcome any delays encountered on the crossing. In normal service, the reciprocating engines (running at 75rpm) and the turbine engine (running at 165rpm) produced around 46,000hp; according to the ship’s registration documents, the engines were registered at 50,000hp; and Harland & Wolff’s Edward Wilding confirmed that the machinery could generate over 55,000hp. In fact, with the main engines running at full speed (about 83rpm) and the turbine at a correspondingly higher pace (about 190rpm), they produced around 59,000hp. Each reciprocating engine on its own could generate as much power as Adriatic’s two engines; Olympic’s propelling machinery was so powerful that it could generate as much power as the engines of all of the ‘Big Four’ combined. Even though the White Star Line were not building the fastest vessels afloat, the power required was, nonetheless, enormous compared to any of their previous ships.

On 18 November 1909, a photographer captured a view of Olympic (on the right) with framing nearly completed, and work proceeding on her sister Titanic (left). The last of Olympic’s hull frames was lifted into position two days later, ‘so that the framing of this enormous ship took just eleven months and five days’. (The Engineer, 1909/Author’s collection)

In a practical manner, various telegraphed orders indicated certain speeds. An order to the engine room for ‘slow ahead’ would request the main engines to run at 30rpm without the turbine in operation; ‘half speed’ would require 50rpm with the turbine operating at 100rpm, and ‘full speed’ would normally need 75rpm for the main engines and 165rpm for the turbine engine, although this depended on the number of boilers in operation and the pressure they were operating at, in addition to how far the engine room ‘stop valve’ was open – this valve controlled the flow of steam from the boilers to the engine room.

Generating sufficient electricity for such a large vessel was a task on a grandiose scale. For this purpose, four 400kW engines and dynamos were installed in the ‘electric engine room’ immediately aft of the turbine engine room. Each indicating about 580hp, the engines ran at 325rpm and took steam at a pressure of 185psi; the engines were each direct-coupled to a continuous current dynamo with an output of 100V and 4,000A, delivering a total output of some 16,000A. As was noted at the time, the supply was more than sufficient for a large-sized city on land. Auxiliary generators were available in the event of the main compartment being flooded:

… there are two 30kW engines and dynamos, placed in a recess of the turbine room at saloon deck D level. Three sets can be supplied with steam from either of several boiler rooms and will be available for emergency purposes. They are of a similar description to the main sets, but the engines of the two-crankshaft type.

These dynamos took steam from boiler rooms 5, 3 and 2 in case several of the boiler rooms were flooded. Comprehensive use of electricity was one marked feature of Olympic