13,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

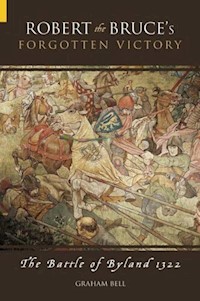

Waged on 14 October 1322, the battle of Byland (an area north-east of Thirsk) was fought between the two monarchs, Edward II and Robert the Bruce, and their forces. The Scots' motive for the engagement was to force the English into accepting the independence that Bannockburn hadn't actually achieved, the aim being to capture the King and force his hand. The plan nearly worked, and Edward II had to make a humiliating escape, losing his baggage train (again), putting his queen, Isabella, dangerously close to capture, and allowing the the Scots to pursue him to the gates of York. This new history of one of Robert the Bruce's most significant victories shows how close the Scots came to capturing the King.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2005

Ähnliche

ROBERT the BRUCE’s

FORGOTTEN VICTORY

ROBERT the BRUCE’s

FORGOTTEN VICTORY

The Battle of Byland 1322

GRAHAM BELL

First published 2005

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

© Graham Bell, 2005, 2013

The right of Graham Bell to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUBISBN 978 0 7524 9643 6

Original typesetting by The History Press

Contents

About the Author

Preface

Introduction

1Scotland: People of Ireland?

2The Margaretsons and the Coming of the Saxons

3David and the Coming of the Normans

4David and the Making of Medieval Scotland

5The Rise of the Feudal Knight and the Growth of Fortifications

6The Battle of the Standard

7The Maiden and the Lyon

8The Final Years of Peace: 1275–1289

9The Struggle for the Throne: Bruce v. Balliol

10The Maid of Norway

11King Bruce? King Balliol?

12Berwick and Dunbar: An End and a Beginning

13The Wallace

14Dumfries

15The Bruce and the Douglas

16Edward II

171307–1314: From Rebellion to Conquest

18Myton and Boroughbridge: Fiasco and Triumph

19‘Slain by the Sword, Slain by the Waters’: The Chapter of Myton

20Byland: Zenith and Nadir

Postscript

Dramatis Personae

Bibliography

Maps and Genealogical Table

List of Illustrations

About the Author

Graham Bell is the author of Yorkshire Battlefields: A Guide to the Great Conflicts on Yorkshire Soil 937–1461 and Famous Yorkshire Deaths. He has an MA in War Studies from King’s College, London and lives in Sheffield.

Preface

In October 1322, on a ridge in Yorkshire, two kings of adjacent areas of Britain faced each other to do battle. It would be the second time the two had met. On the first occasion, one had inflicted on the other the most disastrous defeat suffered by the loser’s kingdom for two-and-a-half centuries; the result of the second encounter would be the same. The difference was that on the second occasion the humiliation suffered by the loser would be one step towards an appallingly brutal and sadistic death in Berkeley Castle; for the other, it would be perhaps the apogee of his kingship and skill as a military commander. This is the story of the battle of Byland.

Unlike the battle of Bannockburn, which (despite the remarks of some of the more cynical historians) in effect ensured Scottish independence, the battle of Byland is unknown even to many of the scholars of the fourteenth century. It had, however, as much treachery, anger and violence as any combat of the age, and allowed the victor, Robert the Bruce, to show skill and daring the like of which can only be compared to the heroism shown by King Harold in 1066, and which would lead to the loser, Edward II, being described by his own people as chicken-hearted and luckless.

The story begins, as most good thrillers do, on a dark night, in a place where the stormy seas lashed the seashore, when all respectable people were in bed. It begins in Scotland in 1289…

Introduction

So utterly vile was the weather in Scotland on the night of i8 March 1286, according to the Lanercost chronicler, that most citizens stayed in their houses. In Edinburgh, King Alexander III of the Scots was attending a meeting of his council. There was a rumour that soon it would be Judgement Day, and that the world would end. Alexander, like most kings, paid very little attention to such absurd ideas, and sent a platter of food to one of his earls, telling him to be merry, as the day of judgement was at hand. The earl replied in the same spirit that if it were, they would meet it with full bellies.

The council appeared to end on this jolly note, and the king took it upon himself to leave the city and cross the Firth of Forth, the stretch of sea to the north of Edinburgh, and visit his wife. He had married Yolande de Dreux only recently and, most inconveniently, she was lodged at Kinghorn, on a rather remote stretch of the Fife coastline, separated from her lord and master by a stormy sea and three miles of rough tracks.

His council tried to stop him on this errand, since the waters of the Forth were stormy, and the road to the house where the queen of the Scots lodged was dangerous (as any road would be on a pitch-black and stormy night). The king, however, overruled his council, deciding to cross over the Forth and perform his conjugal duties, the main duty of a king in the fourteenth century, of course, being to beget healthy and strong heirs.

At the water’s edge, the ferryman urged him to turn back, saying these nocturnal duties would be the death of him. Alexander, with the kingly knack of shaming his subjects into doing his bidding, overruled advice for the second time and set out to visit his queen, who, judging by the risks he was running, must have been a most delectable morsel indeed. On reaching the north shore of the Forth, in the ancient earldom of Fife, the king set out on horseback to Kinghorn. Given the darkness of the night, and the near gale-force winds now raging, it is not surprising that he soon became separated from his guides. It is even less surprising that on the following morning the king’s body was found at the bottom of the cliffs: he had plunged to his death in the night.

This moment of lust and impatience would lead to a series of wars which would go on intermittently for over three centuries, and would only end when the two kingdoms of England and Scotland were united in 1603 by that most unappealing and incompetent creature, James I of England.

1

Scotland: People of Ireland?

The battle of Byland, like all battles, has its antecedents in the history of the armies that fought it. About 500 years after the birth of Christ, Scotland was inhabited by a people described generically as Picts. They left little behind them to tell us of what they were really like, except impressive stone towers and tombs, indecipherable symbols they carved onto stone pillars, and a reputation for savagery and for painting themselves in blue paint.

In about the year AD 560, a group of invaders from Ireland left their home, believed to have been in the county of Armagh, and sailed the short distance east, landing on the west coast of Scotland in modern-day Argyll. Their leader was called Fergus Mac Erc, and they brought with them very little to differentiate them from the Picts (both being Celtic peoples) except for a piece of baggage called the Lia Fiall, or the Stone of Destiny. This was supposed to be the stone on which the ancient prophet Jacob had slept, which had been transported to Scotland in the travels of the Scots via Spain and Ireland.

The Scots and the Picts seem to have lived together in perfect equanimity, an equanimity that was only temporarily interrupted when the Christians made their appearance in Alba (as the ancient kingdom of Scotland was known). The man who converted the Picts and the Scots to Christianity was Columba, an Irish prince who had to make, it appears, a fairly hurried exit from Ireland in about AD 563. By the time of his death in AD 597, the whole of the land had become Christian (according to later historians), and the Isle of Iona on the west coast of Scotland had become the official burial place of the king of the Scots.

We now come to a rather strange occurrence in the history of Scotland. It is known that in AD 843 the king of the Scots, Kenneth Mcalpin, became king of the Picts, most likely through being elected by the Mormaors of Scotland. These men were the great officers of the various areas of the lands of the Picts, who would later be called the Earls of Scotland. They were the Lords of Fife (in later days considered to be the premier area of Scotland), Stratherarn, Angus, Mar, Moray, Ross and Caithness.

Why Kenneth was elected to be the overlord of his Pictish neighbours is something of a mystery. Some have pointed out that at about this time Scotland, like the rest of Christendom, began to be bitterly affected by increasing raids from the Vikings, who were now becoming the terror of the west. Kenneth was a successful warrior, and a good warrior was needed at the helm, especially as the Vikings killed at least two Pictish kings at this time. Suffice to say, Kenneth became king of the Scots and appeared to rule well (which in those days meant being successful in battle), and the line of kings of Scotland would now be called Macalpin for generations.

The next few hundred years followed the pattern of most Christian kingdoms on the continent – in other words, a tale of slaughter and bloodshed as the various kings and Mormaors fought with each other, and sometimes with the Vikings.

It should be pointed out that the orbit of the kingdom was almost entirely to the north of the Firth of Forth, which until well into the thirteenth century was called the Scottish Sea. The land south of the Forth, though originally inhabited by Picts, was now inhabited by a tribe of the Angles who, with their cousins the Jutes and Saxons, had invaded the British mainland in the fifth century. It was these people who would be the most dangerous foes the Scots would ever encounter, and who would to all intents and purposes overwhelm them. As the Picts had rallied under Kenneth Mcalpin, so the peoples of the south rallied under Alfred the Great, the king of Wessex, perhaps the greatest ruler these isles have ever known. By defeating the invading Vikings, and expanding his kingdom to the north, Alfred’s line not only became kings of Wessex, but kings of England.

As Alfred had started the West-Saxon kingdom, the most southerly of the British kingdoms, on its march to greatness, his heirs began to absorb the kingdoms to the north, which had ominous implications for the Scots. Alfred’s grandson, Athelstan the Magnificent, showed the power of the Saxons by leading a huge raid into the heartland of the Scots in AD 934.