Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

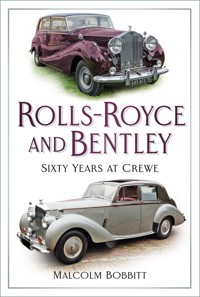

For over sixty years, the Pym's Lane factory in Crewe produced the benchmark of British motoring elegance in its Rolls-Royces and Bentleys. It was the home of the company's car production from World War II until 2002, when its takeover by the Volkswagen Group meant an end to Rolls-Royce production and an expansion of Bentley. In this updated edition of Rolls-Royce and Bentley, motoring expert Malcolm Bobbitt focuses on the evolution of the characteristic models – the Bentley Mk VI and the R-Types, and the Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith, Silver Dawn, Silver Cloud, Silver Shadow and Silver Spirit, together with the Silver Seraph and Bentley Arnage – while remembering the notable figures who played a vital role in the creation of these famous vehicles. Bobbitt illustrates the aftermath of the war on the company's car production and its move from Derby to Crewe, recounting its success in the 1950s and 1960s, the near bankruptcy of the company in the 1970s, its subsequent recovery and final takeover that removed Rolls-Royce from its production line. Within these pages, Bobbitt has cultivated a varied collection of photographs to create a visual account of the history of Rolls-Royce and Bentley cars and to appreciate the company's organisation and its meticulous methods of design, testing and construction that led it to produce these legendary vehicles.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 461

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 1998

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Malcolm Bobbitt, 1998, 2024

The right of Malcolm Bobbitt to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 845 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Chronology

Acknowledgements

Introduction

Chapter One

Derby Days

Chapter Two

Crewe: From Aero-Engines to Cars

Chapter Three

Standardizing the Marques

Chapter Four

Continental Departure

Chapter Five

Gathering Clouds

Chapter Six

Emerging from the Shadows

Chapter Seven

Nothing Succeeds like Success …

Chapter Eight

An Unlikely Alliance

Chapter Nine

Oil on Troubled Waters

Chapter Ten

Mediterranean Interlude

Chapter Eleven

Keeping Up the Spirit

Chapter Twelve

The Millennium and Beyond

CHRONOLOGY

1863

F.H. Royce born.

1877

C.S. Rolls born.

1888

W.O. Bentley born.

1902

Rolls, pioneer motorist, starts up a business selling cars to the aristocracy.

1904

Royce builds his first car; Rolls and Royce meet at the Midland Hotel, Manchester; Rolls-Royce established.

1906

Rolls wins the Isle of Man Tourist Trophy event in a 20hp; Rolls-Royce Ltd registered as a limited company; first 40/50hp chassis produced.

1907

‘Silver Ghost’ sets the world record for an involuntary non-stop endurance run.

1908

Rolls-Royce moves to Derby.

1910

C.S. Rolls killed in a flying accident.

1914

Rolls-Royce asked to produce aero-engines; design work starts on Eagle.

1919

Rolls-Royce-engined Vickers Vimy makes first direct flight across Atlantic; Bentley Motors established.

1921

Springfield works opens.

1922

Twenty Horsepower introduced.

1925

New Phantom (Phantom I) introduced.

1929

‘R’ engine developed for Schneider Trophy which Britain won. Phantom II and 20/25hp introduced.

Due to threat of war shadow factories were constructed in the late 1930s to build aero-engines for Britain’s rapidly expanding air force. One was established at Crewe in 1938 on land at Merrill’s Farm. Production of Merlin engines began on 18 October when the main shop was only one third complete and, on 10 June 1939, less than a year after bulldozers had levelled the land, the first engine was dispatched. This is the office block that fronts on to Pym’s Lane in 1939: note the security guards on duty at the works and office entrances, the unmade road and absence of iron gates. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

1931

Outright winner of Schneider Trophy with R engine; R engine also powers Bluebird, Miss England, Thunderbolt and Speed of the Wind; Bentley Motors acquired by Rolls-Royce. Springfield production ends.

1933

Death of Sir Henry Royce; Bentley 3½ litre introduced.

1936

Merlin aero-engine on test; Bentley 4½ litre announced; Phantom III and 25/30hp introduced.

1938

Crewe factory opens for Merlin production. Wraith introduced.

1939

Park Ward acquired by Rolls-Royce; Bentley Mk V introduced.

1946

Crewe factory converted to car production; Bentley Mk VI and Silver Wraith introduced.

1949

Silver Dawn introduced.

1950

Phantom IV, 4 AF 2, delivered to Princess Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh.

1952

Bentley R-type introduced, modifications over Mk VI apply to Silver Dawn; Continental introduced.

1955

Silver Cloud and Bentley S-type introduced.

1959

Silver Cloud II and S2 introduced along with V8 engine; Rolls-Royce acquire H.J. Mulliner; Phantom V introduced.

1961

Park Ward and H.J. Mulliner become Mulliner Park Ward Ltd.

1962

Silver Cloud III and S3 introduced.

1965

Silver Shadow and T-Series Bentley announced.

1966

Two-door Silver Shadow and Bentley T saloons introduced.

1967

Silver Shadow and Bentley T Convertible introduced.

1968

Phantom VI introduced; GM400 gearbox standard on all cars.

1971

Rolls-Royce in receivership; Rolls-Royce Motors Ltd formed; Corniche introduced.

1975

Camargue introduced.

1977

Silver Shadow II, Silver Wraith II and Bentley T2 introduced.

1980

Rolls-Royce merged with Vickers; Silver Spirit, Silver Spur and Bentley Mulsanne introduced.

1982

Debut of Bentley Mulsanne Turbo.

1984

Bentley Eight introduced.

1985

Bentley Turbo R and Continenetal introduced. 109,000th car built.

1987

Mulsanne S and Corniche II introduced.

1989

Silver Spirit II and Silver Spur II announced. Corniche III introduced.

1991

Bentley Continental R introduced.

1993

Silver Spirit III cars introduced; Bentley Brooklands and Corniche IV introduced.

1994

London coachbuilding operations closed.

1995

Bentley Azure introduced.

1996

Bentley Continental T introduced.

1997

Vickers announce intention to sell Rolls-Royce.

1998

Introduction of Silver Seraph and Bentley Arnage; Rolls-Royce Motors Ltd sold to Volkswagen for £470 million; rights to use Rolls-Royce name and trademarks acquired by BMW for £40 million.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The production of a book of this nature is achieved only by the kindness and often much labour of others. When I started my researches I admit I had some preconceived ideas but I had little idea that my contacts would take me down so many avenues leading to fresh and intriguing information. I should have guessed that this might happen; after all, the subject of Rolls-Royce and Bentley is fascinatingly detailed. Firstly I extend my thanks to Richard Charlesworth, head of public affairs at Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, together with Chris Ladley for allowing me access to company archives and photographic records. I am also indebted to Graham Hull, chief stylist at Rolls-Royce, and to Bernard Preston, director, associate and head of dealer programmes, for giving their valuable time to talk to me.

I make no apologies for the length of the following list of people who have been so supportive in my researches and in particular I thank Martin Bourne and Richard Mann, both long-serving employees of Rolls-Royce and now retired. I feel in many respects this should be their book, considering the wealth of information they have so willingly imparted, and I hope they will accept my apologies for the many hours I have kept them on the telephone and exchanging letters.

I hope those mentioned will forgive me for not acknowledging the exact nature of their assistance due to the amount of space such a duty would involve. My sincere thanks, therefore, to the following: Bill Allen, John Astbury, John Blatchley, Tom C. Clarke, Jill Clowes, John Cooke, Derek Coulson, Roger Cra’ster, Frank Culley, Roland Drew, Joan Elliott, Charles Elson, Clive Evans, René Feller, J. Macraith Fisher, John Gaskell, Jock Knight, Roger Lister, George Ray, Ian Rimmer, Reg Spencer, David Tod, Ian Vetch and Robert Vickers. My thanks also to the many Rolls-Royce and Bentley enthusiasts who have given me their time.

Merlin engines being assembled at Crewe. Although only 208 engines were completed in 1939, annual production exceeded 6,000 by 1943, by which time Rolls-Royce’s workforce numbered almost 10,000, more than at any other time. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

My appreciation must also be recorded to the Sir Henry Royce Memorial Foundation and the Rolls-Royce Enthusiasts’ Club, in particular Peter Baines and Philip Hall. As ever, Annice Collett and her team of librarians at the National Motor Museum have provided so much in the way of assistance. Certainly this book would not have been possible without my publisher and the support and faith shown to me by Rupert Harding.

Finally my sincere appreciation to my wife Jean who has, as always, provided me with untold support and enthusiasm.

Malcolm Bobbitt1998

INTRODUCTION

Sixty days, let alone sixty years, is a long time in the motor industry. That Rolls-Royce survived this duration as an independent manufacturer of motor cars is remarkable enough but to realize the company is far more established than that, extending back to the opening years of the twentieth century, is all the more exceptional. But then Rolls-Royce is a remarkable company and its cars mirror this accolade.

Rolls-Royce has been part of Crewe since 1938 and is now totally synonymous with the Cheshire town. There are still those enthusiasts who consider Derby to be the true home, and some may even argue Manchester, but the inescapable fact is that this very particular motor car has been at Crewe longer than at the other towns.

Had it not been for events that led to the world being plunged into conflict for the second time this century, it is extremely likely this book would not have been written. Car production might have remained at Nightingale Road, Derby, and the land the Pym’s Lane factory now occupies, Merrill’s Farm, could well be still supplying the population of Crewe with vegetable produce.

With threat of war Crewe was selected as the site for one of several shadow factories designed to build up Britain’s defence armoury; in place of horse-drawn ploughs and the chugging of the occasional steam engine or petrol tractor, the noise that filled the air was the sound of the mighty Rolls-Royce Merlin aero-engine being tested. Without the Merlin engine it is doubtful whether Britain’s victory would have been assured. The fact it was is no mean tribute to those who designed and built them, and those who flew in the aeroplanes equipped with them. After the war and with the expansion of commercial aviation, Rolls-Royce’s Derby factory concentrated on aero-engine production. The shadow factory at Crewe became home for the famous motor car, the first postwar examples leaving the works in 1946.

In writing this book I have not merely chronicled the fine cars to have been built at Crewe. The building of the factory, the production of Merlins and the cars which followed in peacetime could not have been achieved without some very experienced people and tremendous team work. A robot can make a car but to give a vehicle an individuality and build in the level of quality and reliability that is revered worldwide, the all-essential ingredient is craftsmanship. Luckily for Rolls-Royce, the company had, and still has, craftspeople for whom anything less than perfection is unacceptable. There is nothing new in all this of course; Henry Royce, mechanic, was such a person, expecting the same from his staff. Those who served under him carried on the tradition, which is evident to this day.

This book is about not only Rolls-Royce but also Bentley, the company it acquired in 1931. Bentley, too, is synonymous with quality, and the name carries more than just an association with motorsport. Without the efforts of the company’s founder, W.O. Bentley, the ‘Bentley Boys’ and the exploits of such personalities as Tim Birkin, Woolf Barnato, Frank Clement, John Duff, S.C.H. (Sammy) Davis and others, together with their achievements at Brooklands and Le Mans, would not have a place in motoring history.

The first Rolls-Royce Silver Seraph leaves the production line in 1998, sixty years after the Crewe factory was established. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

Sixty years is a long time. The tenure at Crewe has not been easy and even from when the first sod of earth was cut at Merrill’s Farm, the race was on to build the Merlin. Before the shell of the factory was complete, engines constructed in less than ideal conditions were on their way to the Front. Even bomb damage, a direct hit from a low-flying enemy aircraft, did not stop production. With the ending of hostilities the factory was re-equipped for car manufacture and new techniques had to be learned; a catastrophic fire could have closed the factory, but it did not. In the 1960s Crewe met a new challenge and adopted quite innovative (for Rolls-Royce) car-making techniques, which proved to be the company’s saviour. Again all was nearly lost in the 1970s when developments in the aero-engine division at Derby forced Rolls-Royce into receivership. A merger with Vickers, the defence and engineering conglomerate, ensued and, following several years of harmony, another era under new ownership is about to begin. At the end of 1997 the news that Vickers intended selling Rolls-Royce Motors Ltd was greeted with dismay at Crewe and by the marque’s many enthusiasts. The outcome, in June 1998, was bizarre to say the least; Volkswagen bought the company from Vickers for £470 million but the rights to use the R-R name and trademarks were acquired by rival bidder BMW from Rolls-Royce Plc, the aero-engine manufacturer.

Throughout the years Crewe has given the world five generations of fine motor cars: the Bentley Mk VI and R-type, the Silver Wraith and Silver Dawn; Silver Clouds, Silver Shadows and their Bentley equivalents; the Silver Spirit, Bentley Mulsanne and, in 1998, the Silver Seraph and Arnage. All these cars have won immense respect. It is also an era which saw the near demise of the Bentley marque – and its phenomenal revival.

The breaking news in the dying months of the twentieth century that Rolls-Royce and Bentley were to divorce sent shock waves through British society. The announcement that Rolls-Royce, an icon of Britishness, had been bought by a foreign business was greeted with disbelief. A victim of this tragic breaking of a long and successful marriage was the Pym’s Lane factory, familiarly known as ‘Royces’ by Crewe’s inhabitants since its construction in the 1930s to build Merlin aero-engines for the approaching war effort.

Two decades since the divergence and sale of these most respected names in the automotive world, the annulment makes for a complex tale with the bidders, BMW and Volkswagen, neither getting exactly what they wanted from what was described as ‘being the auction of the century’. BMW won the Rolls-Royce name while Volkswagen took the Bentley marque along with all its resources, including the Crewe works. BMW started afresh at Goodwood in Sussex with an all-new Rolls-Royce which, in all reality, bore little of the DNA of its forebears, apart from the familiar radiator shell bearing the Spirit of Ecstasy. Volkswagen evolved the Bentley design while carefully retaining its sporting heritage, but no longer are the two revered names synonymous. Ironically, the Bentley factory with its new, but superficial, façade where all references to a bygone era have been eradicated, is still referred to ‘Royces’. If nothing else, this proves that some traditions remain.

This book did not come about by accident. Earlier researches led me to meet many of the individuals who are mentioned in the following pages and their knowledge, expertise, commitment and enthusiasm filled me with awe. Their part in making the postwar Rolls-Royce and Bentley motor cars the fine vehicles they are left me in no doubt that their story should be told. I hope I have done them, and the cars they helped build, justice.

CHAPTER ONE

DERBY DAYS

For the excited crowds that had flocked to Merrill’s Farm on the outskirts of Crewe on 3 September 1932, the droning of distant aero-engines signalled the arrival of Sir Alan Cobham’s Flying Circus. The day before it had been Rhyl and the day after was to be Warrington, just three venues included within a whole series of events around the British Isles that were designed to popularize flying and introduce aviation to the public. Knighted for his services to aviation in 1926, Sir Alan Cobham had first visited Crewe in 1929; so successful had been his flying exhibition then, he was persuaded to return.

It was through the efforts of Sir Alan Cobham and his enterprising air displays that public attention was turned to the plight of the RAF and the fact that in the 1930s it ranked only fifth among the world’s air forces. Cobham’s National Aviation Days had been responsible for establishing many of Britain’s municipal airfields and airports, and later he was noted for charting air routes for Imperial Airways, precursor to BOAC and British Airways.

At Crewe, as elsewhere, the spectators that had gathered at the five-acre field at Merrill’s Farm spent the day enthralled by aerobatics, parachuting, wing-walking and crazy flying. At dusk the aircraft flew off north, the stalls and tents were dismantled and packed away. The crowds, many of whom had tasted aviation for the first time and some who had actually experienced the thrill of flying, wandered back along West Street to their homes. Nobody that day could have dreamed that the world, before the end of the decade, would be dragged into five years of total war, or that the particular field on which they had spent the last few hours was to play a vital part in its course.

The first Royce car, 15196, outside the Cooke Street entrance of the Manchester factory soon after the car had been registered in April 1904. The coachwork, which was painted green, was built by John Roberts of Cavendish Street, Manchester. Note the mud-splattered wings. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

The events that led to the transformation of quiet grazing land into acres of throbbing industry, building the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine which spearheaded Britain’s aerial defences, and thus securing the very future of the nation, were deeply seated in politics. After the First World War the British government had embarked upon a programme of disarmament which, by the end of 1935, had succeeded in running down the Royal Air Force to the extent that it was almost entirely ineffective. Events in Germany that had installed Adolf Hitler as the country’s chancellor were showing the folly of depleting such armed forces, the RAF in particular, and a policy of rebuilding Britain’s armoury, which had been vigorously campaigned for by Winston Churchill, became a priority.

As for Crewe, industry and manufacturing had arrived with the industrial revolution. The rapid growth of the railway system and the establishment of the LMS, the London Midland and Scottish Railway, one of the two main arterial routes that forged northwards from the capital, made the town a major railway centre, its junction becoming the most important on the company’s network. There was little connection with the aircraft industry, however, and even less with the motor industry. Cheshire as a county could not boast of supporting a single car manufacturer of any note before the Second World War. Rolls-Royce, which is now synonymous with the town, had, before the late 1930s, been closely associated with Derby, some forty-five miles to the east and, originally, with Manchester, the great manufacturing town of the north-west.

ROLLS: BALLOONIST, AVIATOR AND PIONEER MOTORIST 1877–1910

Born on 27 August 1877, the Honourable Charles Rolls grew up with the motor car. When he was a young man motoring was virtually unknown in Britain, although it was already established in Europe. At the age of nineteen, in 1896, unlike the great majority of Britons, Rolls had succumbed to the delights the motor car offered and had purchased a 3½hp Daimler-engined Peugeot, the very first motor car seen in Cambridge where he was at university.

In 1900 Rolls won the British Thousand Miles Trial in a Panhard, and in 1905 entered the Brighton Speed Trials. The following year, by which time he was already associated with Henry Royce, Rolls was a contestant in the Tourist Trophy event on the Isle of Man, which he won driving a 20hp Rolls-Royce with Eric Platford, his mechanic. It was not only in the United Kingdom where Rolls achieved fame – he won acclaim in America at the Empire City Track, New York, also in 1906.

As an aviator, Rolls made his first balloon ascent in 1901 and on one of his subsequent flights photographed the Eiffel Tower from the air. He helped form the Aero Club and, from ballooning, Rolls progressed to powered aircraft, becoming the first person to make a double crossing of the English Channel in a single flight.

Rolls was killed on 12 July 1910 when his Wright biplane crashed at Bournemouth. He was the first Briton to die as a result of an aeroplane accident.

COOKE STREET, MANCHESTER

The early history of the Rolls-Royce motor car has been written several times. Therefore, it is not the intention to furnish yet another account of the company’s illustrious past other than to provide a background to this book and to describe some of those events and policies that culminated in the establishment of the Crewe factory. Company roots can be traced back to the opening years of the twentieth century and to the workshop in Cooke Street, Manchester, where Henry Royce, mechanic, operated a successful electrical and crane manufacturing business. His engineering prowess led him to develop his first motor car, the 10hp, because he found no other automobile that met his critical demand for quality.

C.S. Rolls & Co. undertook the selling of Rolls-Royce cars. The letter reproduced here, which only came to light in May 1998, clearly illustrates Rolls’s marketing efforts. (Author’s collection)

Purchased in 1905 by S. Gammell of Countesswells House, Bieldside, Aberdeenshire, 20165, a 10hp, alongside the second production Silver Wraith, WTA2, outside the Blake Street entrance to Royce’s factory. 20165 was donated to Rolls-Royce in 1946 after covering over 100,000 miles. Today the car can be seen in the company’s linear exhibition at Crewe. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

As might be otherwise expected of a fledgling motor car on its maiden journey, cough and splutter it did not; Royce was far too careful to permit that to happen. Instead the car ran as sweetly as the elementary knowledge of the internal combustion engine allowed and the only cacophony was that of company employees cheering and rattling anything in sight to applaud their master. To this day, almost a century after Royce had sampled the joys and trials of taking the wheel of his first motor car, his legacy of care and commitment to engineering excellence and attention to even the smallest detail can be experienced within the company.

C.S. Rolls supervising the refuelling of his 20hp, chassis 26350B. The event is the 1906 Isle of Man Tourist Trophy which Rolls won. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

The Hon. Charles Stewart Rolls, a member of Britain’s aristocracy and a pioneer motorist and aviator, recognizing the Royce car as being the best available, lost no time in selling it to discerning motorists as well as the rich and famous. Happy that his name – which already carried a formidable reputation for quality – be associated with Royce, he promoted the marque in the best manner known to him, by driving it himself in competition with the greatest names in motorsport. It was at the Tourist Trophy (TT) races on the Isle of Man, rivalling Napiers, Darracqs, Arrol-Johnstons and Minervas, that Rolls was victorious in 1906.

The Honourable C.S. Rolls and Henry Royce were from very different backgrounds. Rolls, son of Lord and Lady Llangattock, was born into aristocracy and attended Eton, while Royce, a miller’s son, received little in the way of schooling. Serving an apprenticeship in the railway industry, Royce adopted a keen aptitude for engineering which put him in good stead for a future career. It was unlikely that their paths would have crossed; the fact that they did, however, following a meeting arranged at Manchester’s Midland Hotel by Henry Edmunds, Rolls’s business associate, only proved that there existed between them a convivial relationship. The business partnership that arose from the now famous meeting resulted in the establishment, on 16 March 1906, of Rolls-Royce Limited, a name that has stood for what is considered the best in British engineering ever since.

The poster commemorating the world record for a non-stop motor run achieved by the Silver Ghost in 1907. Illustrated are the architects of Rolls-Royce: Henry Royce, C.S. Rolls and Claude Johnson. Eric Platford became chief tester at Rolls-Royce until his death in 1938. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

With the merging of C.S. Rolls & Co. and Royce Limited to form Rolls-Royce Limited, Rolls was appointed Technical Managing Director and Royce was Chief Engineer and Works Director. Ernest Claremont, previously Royce’s business partner, was elected Chairman and John De Looze, also previously working for Royce, became Company Secretary. Managing Director was Claude Goodman Johnson, Rolls’s business partner, and a powerful and respected figure in the world of pioneer motoring and motorsport. Claude Johnson was a campaigner, an adept organizer, and such was his commitment and loyal service to both Rolls and Royce that he has since become known as the ‘hyphen between Rolls and Royce’.

Rolls-Royce’s reputation was enhanced even further by the Silver Ghost, the most famous car the company has ever produced. The twelfth example of the newly introduced 40/50hp, the first model to be produced under the formation of Rolls-Royce, the Silver Ghost was so named because of its aluminium paint and silver-plated headlamps, not to mention its quiet running. Used as a company demonstration car and often driven by Rolls, this is the car, with its Barker body, that established a world record in 1907 by completing almost 15,000 miles without an involuntary stop. Luckily the Silver Ghost survives to this day; now owned by Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited, it is greeted with much affection wherever it goes and is a powerful means of publicity.

HENRY ROYCE: MECHANIC 1863–1933

Henry Royce was born on 27 March 1863. Following a childhood fraught with hardship and little schooling, he was apprenticed to the Great Northern Railway at Peterborough, something he never completed because he was unable to afford the £20 annual premium the company required.

Moving north to Leeds, Royce found work with an engineering firm, his skills acquired with the GNR putting him in good stead for such a job. He remained at Leeds for no more than a year before moving to London to join the Electric Lighting & Power Generation Company and it was there, combined with electrical work, that he helped develop a wax capsule automatic ceiling-mounted fire extinguisher rose and the Maxim machine-gun. Ironically, Vickers were to build the gun that remained in use until the end of the Second World War, and it is that company which eventually acquired Rolls-Royce.

Another move, to Liverpool in 1882, saw Royce as chief electrician for two years with the Lancashire Maxim Electric Company before the firm went into liquidation. At the age of twenty-one he moved to Manchester and shared a small workshop in Blake Street where he produced bell sets. An acquaintance with Ernest Claremont was established, a business partnership ensued and, in 1888, the two found larger premises at Cooke Street.

From bell sets Royce aspired to building cranes and additional premises at Trafford Park were acquired. At Cooke Street, Royce, having bought a Decauville motor car in 1902, decided he could build a better example, and thus the Royce motor car was born.

CLAUDE JOHNSON 1864–1926

The first secretary of the Royal Automobile Club, Claude Goodman Johnson, is often referred to as the ‘hyphen between Rolls and Royce’. His claims to early British motoring history are many and he was well qualified to write one of the most famous books of all time on the subject, The Early History of Motoring, first published in 1905 in conjunction with The Car Magazine.

Claude Johnson was at the very threshold of the motor industry. He knew all the pioneer manufacturers and designers and had considerable influence when it came to newspaper editors and members of parliament. He was well-travelled, had a gift for organizing and was a real ambassador at home and abroad for the cause of motoring. His true claim to fame arrived in 1896 when, at the suggestion of the then Prince of Wales, he organized an exhibition of motor cars at the Imperial Institute in London.

Just as much a pioneer as Charles Rolls, it was Johnson who successfully organized the selling of the motor car. Having been Rolls’s co-driver in the Paris–Ostend road race in 1900, he joined him in business in 1903. When Rolls met Royce, it was Claude Johnson who successfully maintained the link between the two entrepreneurs. Johnson became managing director of Rolls-Royce on formation of the company and it was he who proved to be the real architect of the firm’s development and success.

NIGHTINGALE ROAD, DERBY

Rolls-Royce moved from Manchester to Derby in 1908. The restricted confines of Cooke Street had presented Royce with difficulties for some time and when the works could no longer sustain production capacity, the inevitable decision to move to larger premises was made. It was Claude Johnson who took control of most of the negotiations and several sites in the Midlands and north-west were considered during 1906. Birmingham and Coventry, already the hub of the British motor industry, were favourites, along with Leicester and Manchester, but it was Derby, a late contender, with an assurance of low rates and preferential electricity, gas and water tariffs, which offered the greatest potential. Royce also favoured Derby because, like Crewe, the town had grown up around its railway industry, and its relatively close proximity to Manchester and reasonable housing prices meant that the majority of his employees were able to transfer with the company.

Rolls-Royce moved from Cooke Street, Manchester, to Nightingale Road, Derby, in July 1908. Arriving for the official opening ceremony is Lord Montagu, one of Britain’s pioneering motorists, being chauffeured by Eric Platford. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

The purpose-built factory in Nightingale Road was ready for occupation in the autumn of 1907 but it was almost a year later before full-scale manufacturing began. The interior was largely designed by Henry Royce himself and under his personal direction was equipped to provide the most efficient production methods. The relocation from Cooke Street was a gradual process, with Royce working to a schedule which ensured there was no loss in production while the move was made. That agenda culminated in an official opening ceremony on 9 July 1908, a grand occasion supported by celebrities throughout the motor industry and the motoring fraternity.

The formative years for Rolls-Royce were a mixture of tragedy and success. Almost exactly two years after the official opening of the Derby works Rolls was killed in a flying accident at Bournemouth. While attempting a steep final approach for a short landing, he overstressed the tail booms of his Short-built Wright biplane, the aircraft broke up in mid-air and plunged to the ground. Rolls was thrown clear of the wreckage but the impact had caused such severe concussion that he died within seconds.

Rolls’s death cast a dark shadow over the company; Royce continued to work at the same extraordinary, almost superhuman, pace he had always done and it was the unrelenting pressures he imposed upon himself that eventually took their toll. Disregard for proper diet and adequate rest resulted in Royce’s collapse within months of his partner’s death; the prognosis was gloomy and his doctors had the uncomfortable task of telling him he had only three months to live.

That Royce survived was viewed as a miracle. His saviour was Claude Johnson who, knowing that all the time Royce stayed at Derby he would be unable to tear himself away from the factory, arranged to take him to the south of France and Italy to convalesce, and to Egypt where they spent the winter. Before departing, Johnson had some organizing to attend to: the day-to-day affairs at Derby he entrusted to three loyal and capable assistants, Arthur Wormald the toolmaker, Tom Haldenby and Eric Platford, all of whom had served their apprenticeship under Royce during the Cooke Street days.

As well as Derby, Rolls-Royce also had a London office, at no. 15 Conduit Street, where C.S. Rolls had established handsome showrooms from where he could sell his prestigious cars. Synonymous with Rolls-Royce for almost the entire period covered by this book, Conduit Street was for many years the company’s London home and shop front to the world. Administration of the premises during Claude Johnson’s absence was placed in the able and willing hands of Lord Herbert Scott, a fellow director of Rolls-Royce.

During the spring of 1911 Claude Johnson returned with Royce to the south of France and it was along the Côte d’Azur near Toulon, at the village of Le Canadel, that Royce, admiring the scenery and feeling comfortable in the area, made Johnson stop the car. After months of enforced rest Royce was on the road to something like recovery and he told Johnson that it was here he would like to build a villa and spend his winters.

The summer months Royce wanted to spend in Britain but Derby, with the air quality usually associated with an industrial area, was out of the question on the advice of his doctor. He nevertheless wanted to be in control of the company, to design and apply his engineering skills while carrying on as normal a life as possible. There had to be a compromise of course, and Claude Johnson decided that if Royce could not go the factory then a part of the factory would go wherever Royce went. At La Mimosa, Royce’s winter residence, and Elmstead, his summer retreat on the south coast at West Wittering near Chichester, studios were arranged where Royce and his design team could work uninterrupted.

These were the days of a one-model policy and the Silver Ghost, which had been introduced in 1906, was still in production. It remained so until 1925 by which time 6,173 cars had been built. Additionally, 1,703 cars were built in the USA, for the north American market, at Springfield, Massachusetts, by Rolls-Royce’s subsidiary company. Claude Johnson had been the advocate of the single-model policy simply because during the early days of motor car production there had been insufficient capital to finance a multi-tooling programme.

The Silver Ghost won many friends. It was clothed in numerous delectable body styles by leading coachbuilders anxious to have their names associated with this fine motor car: Barker, Gurney Nutting, Hooper, H.J. Mulliner, Park Ward, Rippon, Salmons, Vanden Plas and Windovers to mention but a few. Although the one-model policy remained in force for many years, there were variations from the original specification. The 7036cc engine was enlarged to 7428cc in 1909 and in 1913 a 4-speed gearbox with a direct-drive top gear (instead of an overdrive top gear) was introduced. The suspension also came in for some revision and was updated in 1908 to include three-quarter elliptic springs at the rear and, in 1911, cantilever-type rear springs on selected cars. A year later all 40/50hp Silver Ghosts were so equipped.

The Silver Ghost was a most flexible motor car; as well as having the capacity to be driven at walking pace while in top gear, such was the engine’s torque that the vehicle could be propelled, if needed, to almost 80mph. Fitted with a lightweight streamlined body, a Silver Ghost achieved a speed of 101.8mph at Brooklands in 1911.

It was inevitable at some time in the formative years of the company’s history that Rolls-Royce would be involved in aero-engines. Rolls the balloonist and aviator was the first Englishman to fly the English Channel in an aeroplane and the first of any nationality to fly it in both directions. He was awarded his pilot’s certificate on 8 March 1910, the same day that Lord Brabazon had received his pilot’s certificate. Another accolade, somewhat bizarrely, was the fact that he was the first British pilot to die in a powered aeroplane. Had he survived that accident at Bournemouth, Rolls would almost certainly have been looking to Royce to design, or at least modify, an engine that enabled him to fly faster and further than anyone else.

ARMOURED CARS

The connection between aero-engines and motor cars emerged with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Hostilities meant that as far as the motor car was concerned there was a sharp decline in orders but alternative work materialized from two sources, the aero industry and the Admiralty.

Rolls-Royce armoured cars were at the forefront of service during the First World War. The vehicle shown is typical of that fighting on the Western Front. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)

As far as the Admiralty was concerned, it found itself responsible for the Royal Naval Armoured Car Division, a battalion of motor vehicles suitably protected against attack during wartime. Armoured cars, converted Minervas, were first used by the Belgian army in 1914 and their worth was greatly appreciated by patrols as they proved that they could deter advancing enemy cavalry. When the Royal Naval Air Service landed at Ostend in September 1914, to keep the Channel ports open, a detachment of armoured cars was sent to augment the forces. The vehicles were, however, represented by a variety of makes, all with widely differing levels of armour cladding, with the result that there was little uniformity in performance. The best of the detachment were a couple of Rolls-Royces and, as the marque had already achieved considerable notoriety on the war front, the Admiralty recognized the need to equip squadrons with this vehicle.

The Royal Naval Armoured Car Division was thus established under the auspices of Commander Boothby RN. A standard specification of equipment was drawn up: twelve vehicles, all with 3⁄8in armour plating and a machine-gun operated from a steel turret, formed a squadron, and each armoured car was equipped to carry three personnel, although it was customary to deploy just two to avoid discomfort. Each squadron was supported by a team of two or three mechanics together with a cache of parts supplied by the Derby factory to provide a maintenance facility.

The exploits of these vehicles were recognized as being particularly effective and squadrons of armoured cars saw active service on mainland Europe, in the Middle East and north and west Africa in the two world wars. The best description of the cars’ achievements is given by T.E. Lawrence in his book Seven Pillars of Wisdom, where he provides a graphic account of the desert warfare waged by the Rolls-Royces in extremely hostile conditions. Lawrence was moved to write that ‘a Rolls in the desert was above rubies … they were worth hundreds of men in these deserts’.

Armoured cars were not the only Rolls-Royces to encounter service on the front lines of war. Ambulances built on the 40/50hp Silver Ghost chassis – the car’s reliability, tenacious road-holding over even the most dire surfaces and supple suspension made them ideal for this sort of work – performed many a life-saving journey. One particular car, sent to the French war zone in 1914, remained in daily service for three years and over that period carried over 5,000 casualties across the shell-stricken country.

AERO-ENGINES

Work on aero-engines materialized purely out of necessity to defend the nation and, with the cessation of car production at Derby, the factory was put to use building RAF (Royal Aircraft Factory) and Renault air-cooled V8 aero-engines. The need to produce engines for the Allies was so great that Royce reluctantly agreed to their manufacture at Derby, but only until such time that Rolls-Royce could produce a unit of its own to the standard and quality for which it was renowned.

Work started on the first Rolls-Royce aero-engine during the late summer of 1914. Within six months the design work was complete but it was not until the autumn of 1915 that testing began. The Eagle, as the engine was known, was the subject of immense work pressure on behalf of Royce and his design team, who were based on the south coast of Britain and headed by A.G. Elliott, who later rose to the position of the company’s chief engineer. The continual stream of instructions, drawings and calculations that emitted from Royce’s studio were transferred to Derby where Ernest Hives (later Lord Hives), who had joined the company in 1908 to oversee experimental work, took careful control of the building operation.

Although designed with a power output of 200hp, the 12-cylinder, 20.32‑litre, water-cooled Eagle engine, with its two banks of 6 cylinders set in a vee formation of sixty degrees, was nevertheless able to produce 225hp on its initial test run. Royce, Elliott and Hives were not content with what they considered a modest success and set about squeezing even more power from their design. By the spring of 1916 an output of 266hp was established; this rose to 284hp in July and by the end of the year 322hp was obtained. Still not satisfied, Royce and his team worked to increase the engine’s power until 350hp was being delivered by September 1917 and, by the end of the war, the Eagle’s output amounted to a gratifying 360hp at 2000rpm. The fact that there was no need for any major alteration to the original concept, nor that there was any requirement to increase the engine’s cubic capacity, proves the overwhelming soundness of its fundamental design.

Part of the Eagle’s success has to be attributed to W.O. Bentley for it was he who suggested to the Admiralty that aluminium pistons be used in place of steel or cast iron. Bentley in fact worked closely with E.W. Hives in this respect, a liaison which in time was to have dramatic consequences for both Rolls-Royce and Bentley.

By the end of the First World War, Rolls-Royce was supplying 60 per cent of the total production of all British-built aero-engines and thus this element of the company’s affairs was securely established at Derby. Other designs followed: the Hawk, which was accepted as the most favoured means of powering naval airships; the Condor, a larger version of the Eagle and used in a wide variety of British aircraft; the Falcon, a scaled-down Eagle and successfully used in the Bristol F.2B fighter; the Kestrel and Buzzard, both of which shared a similar design layout and were applied to various aircraft designs during the 1920s.

Of particular significance in the history of the company were two events, both of which occurred during 1919, and which were of international importance. The foremost was the first direct crossing of the north Atlantic by powered flight when Alcock and Brown, in a Vickers Vimy with its two Rolls-Royce Eagle VIIIs, departed from Newfoundland on 14 June. They landed safely the following day in Ireland, despite a flight in terrible weather conditions which took sixteen hours and twelve minutes to complete.

The second event, which was of no lesser importance, was the inaugural flight from Britain to Australia by Ross and Keith Smith, also in an Eagle-powered Vimy. The harrowing journey of 11,300 miles took a total of 28 days with 124 hours actual flying time, and the expedition caught the romantic imagination of the world’s media. Aviators continued their epic explorations of the world’s skies, opening up countries and continents and establishing important trade routes, which would later be flown in a fraction of the time originally taken. The fact that Rolls-Royce engines and expertise played such a substantial part in aviation history is highly significant.

Built between 1906 and 1926, the 40/50hp, often referred to as the Silver Ghost, was undoubtedly Henry Royce’s greatest design. This wonderfully evocative photograph showing a car being ferried across a loch in Scotland is, unfortunately, undated. The chassis number of the car is unknown but the registration relates to Denbighshire, the series being issued from January 1905. (Courtesy: Mark Morris, Autovisage, and Rolls-Royce Enthusiasts’ Club/The Sir Henry Royce Memorial Foundation)

The end of the First World War saw a resumption of car manufacturing at Derby. This was important, not only because pre-war Rolls-Royce cars had amassed such a degree of respect among discerning motorists and that the exploits of the 40/50hp Silver Ghost in particular had achieved a formidable reputation for reliability at the war front, but also because demand for the motor car was undoubtedly going to be enormous. A further factor concerned the aviation industry itself; with the war over, the market for aero-engines in a military context was expected to diminish.

For Rolls-Royce, however, the company’s dual role of manufacturing motor cars and aero-engines was firmly established. The usefulness of the military aeroplane in wartime had clearly demonstrated there was a strong future for commercial aviation, a fact plainly illustrated by Sir Alan Cobham’s pioneering 22,000-mile round trip from Britain to South Africa, the Short Singapore flying boat powered by two Condor series IIIA engines effortlessly completing the journey in 250 hours flying time.

FUTURE ARCHITECTS

With the ending of one era and the beginning of another, there is need for a few words on a couple of Rolls-Royce’s personnel of the period who, despite having joined the company only a short time before, would command a great deal of direction and influence in ensuing years. Under Ernest Hives at Derby was an apprentice, W.A. Robotham, who was appointed a technical assistant in the Experimental Department in 1923 and whose forte was chassis design. Ivan Evernden joined the company in 1916 and worked on airship and engine design until 1922 when Royce chose him to work with him at his studio at West Wittering. Robotham became recognized as the architect of the rationalization policy at the end of the 1930s and Evernden as the stylist of some of Rolls-Royce’s most prestigious motor cars.

With all the frenetic energy that had been spent developing aero-engines, little time during the war years was given to any real thought of car production until hostilities were over. Claude Johnson’s one-model policy was still in force and the building of the 40/50hp continued more or less where it had been left off in 1914. Experimental work had always been Royce’s philosophy and it is understandable, therefore, that serious development began on a range of machines with similar proportions to the Silver Ghost. These attracted the EX notation and culminated as the New Phantom models but consideration was also given to producing a smaller, more popular vehicle, which was given a G notation and code-named ‘Goshawk’.

The perception of Goshawk came about simply by the fact that demand for large and luxurious motor cars would, postwar, be diminished and that the company could profit from a smaller and less powerful machine, provided that the Rolls-Royce traditions of attention to detail and engineering excellence were maintained. The outcome was the Twenty Horsepower which was introduced in 1922. Despite a relative lack of performance, the car’s 3-litre, 6-cylinder engine nevertheless offered refined but subdued motoring and proved a popular choice for the discerning motorist and owner/driver, who had a regard for comfort rather than spirited acceleration and a high top speed.

There were, perhaps, two departures from previous models that drivers of these cars regretted; the right-hand gear change and the enclosed propeller shaft. Specification of the Twenty had allowed for a central gearlever which, in the modern motor car, Rolls-Royce and Bentley included, is not only expected but taken for granted. For those who bought the Twenty, little enthusiasm for the centre gear change existed and the company, when devising a 4-speed gearbox in 1925 to incorporate servo for the 4-wheel braking system, seized the opportunity to locate the gearlever to the driver’s right. And that is where it stayed on manually operated right-hand drive cars, except for a very few Bentley models, until well into the postwar years. As for the propeller shaft design, this was perceived by some as being a retrograde step; as far as Royce was concerned, however, he was completely satisfied that it met his approval, and who can argue at that?

The Twenty, despite some owners’ views concerning the vehicle’s performance, was a very capable car and has acquired a considerable following since its introduction. Development of the model ensured that it enjoyed a long production run, spanning two decades and embracing two subsequent derivations, the 20/25hp in 1929 and the 25/30hp in 1936.

Early examples of the Twenty are identified by their style of radiator that incorporated horizontal shutters (initially they were finished in black enamel but were later designed in German silver, thus matching the shell), and which could be adjusted via a manual device from the driving position to aid the warm-up period when the engine was cold. Later examples were fitted with vertical shutters, as were the 20/25hp and 25/30hp models.

A need to up-rate the power of the Twenty, which resulted in the introduction of the 20/25hp with its 3669cc engine, came about largely due to the use of heavier bodies, which somewhat impaired the car’s performance. Many marque enthusiasts claim the 20hp models – and the 20/25 in particular – to be the most satisfying of the interwar Rolls-Royce’s to drive, which probably explains why there were almost as many of this type produced (3,824) as the 20hp and 25/30hp (introduced in 1936) combined (4,113).

While the 20hp cars were being developed, work was also progressing on an updated Silver Ghost. Despite the period of austerity following the war there was, nevertheless, a demand for luxury vehicles which only the type and style of the larger and more powerful Rolls-Royce could satisfy. Successor to the Silver Ghost was the 1925 New Phantom, a name that has largely been superseded by the nomenclature Phantom I. Produced until 1929 in relatively small numbers (2,212 were built) the New Phantom’s chassis, which was virtually identical to that of the last 40/50hp, proved somewhat uncompromising, the 7668cc engine producing more power than it could support.

If these comments appear disparaging, they are certainly not meant to be, especially in view that the EX programme was producing some remarkable results, particularly at Brooklands, where experimental cars, fitted with touring and sports bodies, were achieving impressive lap times. Royce was aware of criticism that the 40/50hp was old-fashioned, and that its performance was lacking, and it was to W.A. Robotham that he entrusted much of the Sports Phantom’s testing. It was no mean effort, therefore, when a car built on chassis 10EX thundered around the Weybridge circuit with a best lap speed of 91.2mph.

An important development in the Rolls-Royce range of motor cars was the introduction of the Phantom II in 1929, which effectively signalled a new era as far as chassis design was concerned. The Ghost of the original 40/50hp had finally been laid to rest, the Phantom II’s chassis sharing a corporate identity with that of the 20hp cars. Much revered by marque enthusiasts, the Phantom II is constantly being regarded as the finest Rolls-Royce ever built. The construction of the chassis allowed coachbuilders to produce some striking designs which, with the car’s long bonnet and radiator set back aft of the front axle, were often delightfully sleek and very well-proportioned. A year after the Phantom II’s introduction, a Continental version became available that added an extra degree of performance and panache to the range of cars. Built on a shorter and therefore lighter weight chassis than the original Phantom II, this is the car that could achieve a maximum speed of over 90mph, the 7.6-litre straight-six engine propelling the 2½-ton laden weight from resting to 60mph in under twenty seconds. The Phantom II’s introduction, however, was just one of several significant events in a particularly turbulent era of company history.

The death of Claude Johnson was announced on 11 April 1926; this man of great foresight, who had been at the leading edge of the company from 1906, was almost directly responsible for many of the company’s major decisions and, ultimately, its undeniable success. It was Claude Johnson who had campaigned so arduously on behalf of Rolls and Royce; who advocated the single-model policy to avoid too much of a strain upon resources; who undoubtedly extended the life of Henry Royce; who smoothed the way ahead with governmental departments during particularly trying times when the company was developing aero-engines during the First World War; whose loyalty to the company was unfailing and was deservedly commemorated by the installation of a memorial at the front of the Derby works. Possibly the best tribute to Claude Johnson is the famous Rolls-Royce radiator; the design’s precise origins are a matter of some conjecture but what is certain is that it was Johnson who argued to retain its existence, especially as Henry Royce was at times in favour of changing it for something more simple and easier to manufacture. In his opinion, Claude Johnson believed a motor car as prestigious as the Rolls-Royce should have a completely distinctive trademark.

THE SCHNEIDER TROPHY

The late 1920s were significant for Rolls-Royce’s involvement in aero-engine development and the company’s commitment to Britain’s bid to win the Schneider Trophy, an event which, since its inception in December 1912, had been responsible for pushing the limits in aviation technology further than any other. The trophy, which was presented by the Frenchman Jacques Schneider to foster development of the seaplane, was first staged at Monaco in 1913 and it was therefore fitting that the initial event was held in France and won by Maurice Prévost, a fellow Frenchman. The following year the trophy was presented to Britain in recognition of Howard Pixton’s achievement in a Sopwith Tabloid floatplane. Schneider had added the stipulation that any country winning the trophy on three successive occasions would own it; that the trophy is Britain’s is a recognition of Henry Royce and his loyal team at Derby.

Synonymous with the Schneider Trophy is R.J. Mitchell’s Supermarine floatplanes, the S5, S6 and S6B, the latter capturing outright the trophy for the British. Mitchell, born in 1895, was hired by Supermarine in 1916 and within three years became the firm’s chief engineer, a responsibility which also entailed designing high-speed flying boats. During the early 1930s Mitchell turned his attention towards designing a fighter and it was while on a visit to Austria that he anticipated the requirement for such an aircraft was imminent. Although ill with cancer, he nevertheless concentrated on perfecting the fighter’s design, which materialized as the Spitfire, possibly the most famous aircraft in history. Although Mitchell died in June 1937 his legacy remains.

The 1927 Schneider Trophy had been won by Flight Lieutenant S.N. Webster in a Napier Lion-powered Supermarine S5, and it was therefore Britain’s responsibility to stage the subsequent contest, which was held in the Solent in 1929. The Napier engine had reached the peak of its development and if Britain were to retain the trophy for the second year running it was obvious that a more powerful engine would have to be built. Henry Royce was invited to build a suitable engine but because of the limited timescale an entirely new design was out of the question. The decision was taken to develop the Buzzard engine, the design being known as the ‘R’. Although the R engine shared many of the Buzzard’s features, it was quite different in appearance, much emphasis being placed on the reduction of cross-sectional area to aid streamlining.

On its first test run a power output of 1545hp at 2750rpm was achieved but with careful development this was increased to 1900hp at 3000rpm. Such endeavours were quite intense and often Rolls-Royce engineers were called back to work during unsociable hours to perfect different aspects of the design. The engine test runs were naturally noisy and the excessive roar of the exhaust note, audible throughout Derby, became known as the ‘Derby hum’.

Bentley Motors Ltd was formed in 1919 but it was not until January 1920 that Sammy Davis of The Autocar tested and acclaimed the car. In this photograph, taken at Le Mans in 1924, W.O. Bentley is standing between Frank Clement, chief tester, and John Duff: the car is a Bentley 3-litre. In the background can be seen A.F.C. Hillstead, author of Those Bentley Days. (Courtesy: Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Limited)