18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

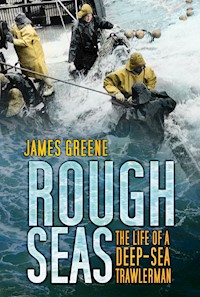

A trawlerman's life was hard, often up against bad weather, rough seas and black frosts, although on calm days it was a pleasure to be at sea. In this eventful memoir, deep-sea trawlerman James Greene relates his life at sea, from his childhood when his father would take him out in some of the worst gales and hurricanes imaginable to his early career as a deckhand learner, obtaining his skipper's ticket, and the many experiences – both disastrous and otherwise – to occur throughout his time at sea. During his career he was involved in ship collisions and fires, arrested for poaching, fired upon by Icelandic gunboats, in countless storms and even swept overboard in icy conditions off the Russian coast. The British trawling industry is largely a bygone age and people are beginning to forget the adventures, hardships and joys that characterised this most dangerous of professions. This book seeks to keep the memories of a once great industry alive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Chapter 1 Hayburn Wyke, 1938

Chapter 2 War Years, 1939 to 1945

Chapter 3 Comitatus, 1946 to 1952

Chapter 4 The Great Storm of 1953

Chapter 5 St Philip, 1953

Chapter 6 Hildina, 1953

Chapter 7 St Leonard, 1954

Chapter 8 St Kilda

Chapter 9 Northern Duke, Grimsby, 1954

Chapter 10 Northern Chief, GY 128, 1954

Chapter 11 Northern Jewel, GY 1, 1955

Chapter 12 Prince Charles, 1955

Chapter 13 Starting as a Deckhand, 1955

Chapter 14 Northern Sky, 1956

Chapter 15 Loss of the Liberty Ship Pelagia, 1956

Chapter 16 Royal Lincs, September 1957

Chapter 17 Equerry, 1957

Chapter 18 Bombardier, January 1958

Chapter 19 Northern Foam, 1959

Chapter 20 Northern Sceptre, 1959/60

Chapter 21 Northern Pride, 1960

Chapter 22 Northern Sky, 1960

Chapter 23 Serron, 1961

Chapter 24 The Ross Group, 1961/2, Reperio

Chapter 25 Sir Thomas Robinson & Sons, 1961

Chapter 26 Thessalonian, 1962

Chapter 27 MT Rhodesian, 1963

Chapter 28 Judean, October 1964/65

Chapter 29 Syerston, 1966/67

Chapter 30 Port Vale, 1968

Chapter 31 Triple Tragedy, 1968

Chapter 32 Back to Robinson’s, 1968

Chapter 33 Ross Tiger, 1972

Chapter 34 Osako, 1973

Chapter 35 Spying on British Trawlers

Chapter 36 Ross Jaguar, 1978

Chapter 37 Ross Jackal, 1984

Glossary

Plate Section

Copyright

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Amy Rigg, Emily Locke, Kerry Green and The History Press for all their help; Austin Mitchell for all his help; the late Dolly Hardy who did a lot of hard work to get fishermen compensation; Eric Fearnely, Photographers, Grimsby; Grimsby Central Library; Grimsby Heritage Centre; Innes Photographers, Hessle Road, Hull; Jamie Macaskill, Hull Daily Mail; Janeen Willis & Fred Goodman, photographic collection; Jim Porter, administrator at Fleetwood-Trawlers.info; Lyne Asgha, Fleetwood Museum; Mary Houghton for ‘The Last Voyage’ by her father in chapter 12; excellent photographs from Memory Lane, 528 Hessle Road, Hull; Michelle Lalor at the Grimsby Telegraph; my daughter Alison for all her help on the computer; Steve Farrow for the use of his wonderful paintings; Susan Capes at the Hull Museum & Art Gallery; the US Coastguard; William H. Ewen, Steamship Historical Society of America.

FOREWORD

I am delighted to welcome Jim Greene’s excellent autobiography because it’s not only his own life story, but a marvellous insight into the industry in which he served. We won’t see the like of either again so it’s good that Jim has not only told the tale of fishermen like him who spent most of their lives in peril on the sea, but gives us a fascinating picture of the rise and fall of our once great fishing industry. Fishing shaped the lives and built the fortunes of the three great English fishing ports of Grimsby, Fleetwood and Hull, but was almost totally destroyed by the world trend to 200-mile limits and by our own inability to rebuild fishing in our own rich waters thanks to a Common Fisheries Policy which gave equal access to a common resource, meaning that our rich fishing grounds were open to the French, the Dutch, the Danes, and others all managed not by us for our purposes but by the European Commission doling out paper fish in political decisions taken in Brussels.

Jim’s life brings home the drama, the dangers, the highs and the lows of the lives of the thousands of fishermen who toiled in our distant water fishing industry up to the time when it suddenly found itself with nowhere to fish, and that story deserves to be told and remembered before the last generation of distant water fishermen fades into history, as most of their industry has already done. In Jim’s day Grimsby boasted of being the World’s Premier Fishing Port, a title disputed by Hull but rightfully ours because, though Hull caught more fish and regularly won the annual Silver Cod award, Grimsby caught quality rather than quantity and had a bigger and more diversified fleet fishing middle and near waters as well as Iceland, Greenland, the Faroes, Norway and even Canada.

So Jim is describing not just an industry, which was very profitable for the men and even more so for the big powerful owners who ran it, but a way of life unique to the three ports where fishermen lived in tight fishing communities of terraced housing clustered round the docks, sons followed fathers, as Jim did his, and wives raised the families while absentee fathers fished for three weeks away, then home for perhaps three days.

The men faced the restless waves and the distant waters but spent much of their time when ashore in the rough, tough world ‘Down Dock’ from which men, money and life spilled out into the surrounding streets, particularly in Freeman Street, Grimsby, with its pubs, shops, markets, training facilities and schools. Down Dock was the focus of fishing life and an almost tribal existence. The offices, the engineering, provisioning, landing marketing and auctioning of the fish all carried on there and the merchants’ and owners’ premises clustered round the market from which the precious fish were despatched by rail, up to Dr Beeching’s railway cuts, then by road out to the waiting world.

Down Dock was a tough, male, insular world somewhat separated from the rest of Grimsby, as was Hessle Road in Hull and the fishing streets of Fleetwood. Fishing made the towns rich but in return the respectable burghers looked down, almost askance, at the industry and the men who’d generated the wealth of their towns. Down Dock was another world, one where fishermen worked, lived and strutted the nearby streets like kings, even though, in fact, they were lashed to their industry like seaborne serfs by the powerful cartel of fishing vessel owners whose word was law.

It’s good and right that that way of life should be written up for history and Jim Greene has done a marvellous job in recreating the industry by telling his own life story simply and honestly and without pretension or stylistic tricks for the future generations who’ll never see its like again. With all its toughness, tragedies and terrors in distant waters our big, English fishing industry has gone, leaving perhaps a score of middle water vessels in Grimsby, a few freezers in Hull and a small remnant, some Spanish owned, in Fleetwood. The fishing communities have been broken up, their continuities and lifestyle destroyed. Believe it or not, it’s now difficult to recruit fishermen in the old ports because so few youngsters want to go into an industry to which most once flocked. Jim never wanted his own son to go into the industry to which he’d devoted his own life.

The death of fishing was sad, even shocking, because a once powerful industry was scuttled. Its vessels were sold off, sent to Spain, Africa or anywhere which could pay, or scrapped. Its owners, well compensated by the government, put the money in their pockets and scattered, leaving the towns that had made them and taking their money with them. The men were thrown onto the scrapheap with neither compensation nor redundancy because these slaves of the sea were viewed as ‘casual’. Neither was paid until a tribunal case in 1994 proved that fishermen were in fact employed, not the casual workers this almost captive workforce had (unbelievably) been seen as in 1976. Then only thirty years after the death of the industry and after a long struggle by the British Fishermen’s Association, by Dolly Hardie and by the port MPs, the Labour Government paid compensation for the loss of jobs and livelihood, a compensation which is only now being grudgingly and unfairly finalised. No other group of workers had such a hard, dangerous life. None has been as badly treated.

There is no point in me telling that part of the story over again. Jim Greene tells the whole story brilliantly in his own words through the narrative of his life, starting in Fleetwood, moving upmarket to Grimsby, fishing first as deckie learner, then mate and finally skipper. He was one of the youngest, too, but thank heavens his tough life has been remembered and preserved forever as it deserves to be. Enjoy.

Austin Mitchell

MP for Grimsby

CHAPTER 1

HAYBURN WYKE, 1938

It was a cold, stormy night in March 1938, the month and year I was born. Somewhere off the west coast of Scotland the Fleetwood coal-fired steam trawler Hayburn Wyke was dodging, her bow ploughing into the teeth of a storm. Fishing operations had been suspended due to the bad weather. All crew were sleeping except for two men on watch in the wheelhouse and the chief engineer and his firemen working hard to shovel coal into the furnaces to keep fires going and the engine running smoothly.

In the wheelhouse the watch kept a sharp lookout for other ships while the bosun studied the weather. An ice cold wind whistled through the wheelhouse, in darkness except for a small light that lit the compass. The only other light came from the depth sounder flashing at regular intervals. It was noisy; the windows rattled in the gale and the ship was constantly battered by heavy spray. The wind ripped through the rigging, howling like some tortured creature lost in the night.

The man at the wheel struggled, constantly fighting as the trawler kicked and pulled, desperate to keep the ship’s head to wind. The night was clear, visibility good with a bright moon shining. Briefly the islands of St Kilda stood proudly on the horizon bathed in the light of the moon, only to disappear again as the next wave loomed and blotted them out. Every now and again a large sea would build up in a threatening manner, to drop away to nothing as it reached the bow.

The bosun watched the following sea; he knew it posed a serious threat. The helmsman had already spotted it and clung to the wheel. The sea was now a sheer wall of water starting to break; they watched in horror as it curled over the bow, sending tons of water crashing onto the deck. An almighty bang was heard from somewhere aft.

The wheel was wrenched from the helmsman’s grip, spinning crazily like some out of control fairground ride. He made another grab for it, trying to regain control, but was too late: it was slack in his hands. The ship was rapidly turning to starboard, broadside to the heavy seas.

Now helplessly out of control with a smashed rudder, the bosun was first to react. He ran to the telegraph to stop the engine. On hearing the commotion the skipper, sensing something was seriously amiss, leapt from his bunk. Grabbing his Guernsey, muffler and cap he hurried to the wheelhouse. He contacted nearby trawler Dinamar requesting she stand by until the weather eased down or they could begin repairs. The other ship agreed to do all in their power to assist.

Several hours passed, the weather improved slightly and the crew worked relentlessly to rig up temporary steering gear enabling them to get closer to St Kilda and more sheltered waters. As they headed for calmer water the skipper and mate discussed a more permanent repair idea: to hang one of the trawl doors under the counter of the stern using chains and shackles. A warp from each side of the trawl winch would run down both sides of the ship and be shackled to the trawl door. The steam winch could then be used to control the emergency rudder.

The first job was to pump tons of water down the forepeak to sink the bow and lift the stern out of the water, enabling the crew to work underneath. A difficult task indeed; the ship pitched and rolled in the heavy seas and as waves broke over them she drifted further from land and shelter. The lifeboat was launched with the skipper, bosun and two deckhands on board. There was the danger that the lifeboat would get caught under the stern, capsize and throw the occupants into the sea.

One brave deckhand offered to swim round the stern to secure a shackle to the smashed rudder. The skipper wouldn’t allow it, it was just too dangerous.

With great difficulty they managed to heave the trawl door over the side and suspend it on a chain over the stern. The door, made of wood and steel, weighed around 1.5 tons. Several times it swung too close to the lifeboat causing great concern to all.

Once in position it was heaved tight into the ship’s stern and secured with chains and shackles. The warps from the winch were shackled to the door. By heaving and lowering the warp they managed to steer the ship.

Sunday lunchtime and work was eventually finished. The lifeboat was back on board and lashed down, the decks cleared away and the trawl doors stowed. However, during operations the derrick had swung across the deck and smashed into the skipper, injuring his shoulder.

The crew had worked non-stop for thirty-six hours at the mercy of the gale to get the job done. Despite being exhausted, wet, cold and with aching limbs both skipper and crew felt a sense of pride at what they had achieved.

By standing at the winch on the windswept deck, heaving and slackening the warps as required, they were just able to steer. Twice on the way back to Fleetwood the warps parted. The ship drifted helplessly towards land as warps were spliced (repaired). For 300 miles they struggled to get back home.

A tug stood by to tow them in when they reached Wyre Light just off Fleetwood. Even then worries weren’t over; the tow rope parted three times. Each time they drifted up Morecombe Bay before the tug could retrieve them. With the exception of the skipper who was twenty-eight, not one crew member was more than twenty-four years old.

It was seen as a magnificent feat of seamanship. Awards were made to skipper and crew. It was thought this was the first time a trawler had been able to effect repairs of this nature in such a storm, without having to be towed home by another vessel.

The skipper received the grand sum of £36 10s 6d from the insurance company.

That skipper was my dad.

CHAPTER 2

WAR YEARS, 1939 TO 1945

The Second World War broke out the following year, September 1939. Dad joined the Royal Naval Reserves (RNR) as acting skipper lieutenant. He was injured in action three times during his first year at war. In the English Channel on 25 November 1940 he was on the HMT Kennymore when she was blown up and sunk. He was rescued with the other survivors by HMT Conquistador. On her way, the Conquistador was in collision with HMT Capricornus, which suffered damage to her bow, but Conquistador was severely damaged, sank and again Dad was rescued, I assume by the Capricornus. He was taken into port where he spent six months in hospital at Sheerness.

On 7 December 1940 the Capricornus was herself blown up by a mine and sank.

As Dad had spent several years as skipper of the Hayburn Wyke he put in a request to return as skipper on her but the Royal Navy turned him down. The Hayburn Wyke was torpedoed and sunk by a U-boat while anchored off Ostend on 2 January 1945. In the Civil Honours List Dad was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) for bravery in the face of enemy action.

As children we lived in a three-bedroomed house, middle of a row of three, on Broadway, the main road between Fleetwood and Blackpool, with the added luxury of a bathroom and toilet upstairs.

At the outbreak of war we were issued gas masks. They came in a cardboard box with a shoulder strap and we were instructed to take them everywhere with us. They even manufactured them for small babies. When I first tried mine it wasn’t a pleasant experience, let me tell you! It was very claustrophobic; I started breathing fast and felt like I was suffocating. I panicked and pulled it off. Once I got used to it it wasn’t too bad, but I never put it on unless told to!

The war years were very hard for my mother. At the outbreak of the war there were four of us. Betty was the eldest at six years old, Odette was four, Billy two and I was just a year old. In 1940 Pat was born followed in 1942 by Peter. It must have been difficult for my mother with six children to feed and clothe and everything scarce or rationed. It got so bad that one time Betty was sent to Grandma’s in Preston as food was so short.

At one stage Odette was found to have diphtheria and was sent to hospital in Moss Side near Manchester. The diphtheria virus being so contagious, all the rooms in the house were treated – systematically sprayed then sealed up, how long for I really can’t recall.

Another time Pat contracted bronchial pneumonia. She was in hospital for almost a year, very seriously ill. I believe she was the first person in Fleetwood to receive penicillin.

The lowest point for us all was when our mother went into hospital. She suffered with leg ulcers and they’d become so bad she had to be admitted. The authorities I think considered taking us into care but Grandma saved the day. She came to Fleetwood to look after us so we could all stay together at home.

During the war three bombs were dropped on Fleetwood. One aimed at the ICI plant but missed. I’m surprised there weren’t more because the ICI plant was one of the biggest in the country.

We always looked forward to Dad coming home; he always brought us a present and gave us a florin and an orange each, a rarity back then. He’d bring home Turkish delight too but I wasn’t keen on it! He spent time in Egypt during the war and he’d bring home lovely jewellery for my mother.

We thought we had it bad but we got off lightly compared to the big towns and cities like London, Coventry and the like – even Hull and Grimsby got it bad.

The Grimsby dock tower started its working life in 1852, officially opened in 1854 by Queen Victoria. In 1931 a large earthquake on the Dogger Bank measuring 6.1 on the Richter Scale shook the tower but it remained structurally sound. During the war it survived the bombing of Grimsby as it was a useful landmark to the Luftwaffe, being a reference point to fly due west to Liverpool. On their way back to Germany any bombs left were dropped on Grimsby and Hull before crossing the North Sea back to Germany. If an aircraft was damaged there was no way they wanted to crash land on their own soil with bombs on board.

So we had it easy compared to others. My then future wife lived on the Thames in Erith and some of the stories she can tell are terrifying. They were bombed repeatedly night after night as they lived close to Woolwich Arsenal, a huge target. For years after she was absolutely terrified of thunderstorms.

We were lucky as my dad returned home safe from the war. I knew a lot of boys and girls at school whose dads didn’t, and they were the ones that had it hard after the war. I hardly remember much more about it all as I was too young.

CHAPTER 3

COMITATUS, 1946 TO 1952

After the war Dad returned to Fleetwood and took command of the Fleetwood coal-fired steam trawler Comitatus. Registered GN 39 and built in Beverly in 1919, she was 120ft in length and weighed 108 tons.

I was eight years old; I’d never given much thought to going to sea, although my friends and I were mad about trawlers and fishing. It came out of the blue when Dad said he was going take Bill and me to sea with him. It was the best present I could have wished for. It was like a birthday and Christmas rolled into one. Talk about being excited; I was out of that house like a shot to tell my mates. The down side was it wouldn’t be on his next trip as we’d not broken up from school for the summer holidays. We had to wait a whole two weeks!

Mother took us into town to get warm clothes and wellingtons. Dad was still at sea and I kept pestering her to find out when he was coming in. She said I was getting on her nerves, I couldn’t think why!

I’d go down to the prom at Fleetwood when Dad came in, or the Jubilee Quay where the Isle of Man boat was berthed. You could shout and wave to the crew from there as they came so close to the quay. Dad would give us a blow on the ship’s whistle. You could tell when it was coming as a plume of white steam came from the whistle on the funnel seconds before you heard it, a real deep sound you could feel vibrating in the pit of your stomach.

The night before we sailed it was early to bed, a complete waste of time as there was not much sleep to be had. It seemed like the longest night of my life. The taxi was ordered for 5.00a.m. that morning. We were up and ready – the taxi was late. I started to think they’d forgotten us. The taxi arrived at 5.15a.m. Finally we were off! I could hardly contain my excitement.

We stopped off on the way to pick up Bill’s friend. We arrived on the docks at 5.45a.m. There was a lot hustle and bustle going on, taxis arriving, doors slamming as crews arrived for sailing. There were about seven or eight ships due to sail that morning. My dad’s friend George Beech was skipper on one of them, the Buldly. Also sailing that morning was the Wyre Mariner and the Bridesmaid on which my granddad was bosun.

The ship’s runner had his work cut out. His job was to make sure all the crews were down and the ship’s sailed on time. When the crews were down he would inform the lock gates. The first ship ready was the first ship to sail. Our ship was ready when we arrived at the dockside; the shore gang had been down since midnight to get the fires going ensuring there was plenty of steam in the boilers ready for sailing.

The sun was just rising; there was a light easterly breeze blowing with a distinct chill that sent shivers through my body. The air was filled with the smell of steam and coal smoke as it drifted lazily about the docks on the light breeze. At around 6.00a.m. the dock gates opened and we climbed aboard. The ship’s ladder was pulled on to the quayside. We were the fourth ship to sail that morning.

We had to wait until the ship’s name was called out on the loud hailer at the lock gates. After what seemed an eternity, Comitatus was called. The crew wereon the whale back, Dad and mate on the bridge. Two men worked the after ropes.

‘Let go forward,’ Dad shouted.

The ship’s runner threw the ropes off the quayside bollard and let them slide into the water. The men on the bow pulled them on board and they were stowed away ready for sea.

The ship’s telegraph jangled with a hiss of steam, and you could hear the thump of the steam engines as they sprang into life. The whole ship trembled as we came slowly astern; the after mooring rope came tight as it took the weight of the ship. The ship’s bow started to move away from the quayside. When the bow had cleared the two ships moored in front, Dad shouted, ‘Let go aft!’

The after rope was slipped then pulled back on board. We slowly made our way across the dock to the lock gates.

It was a smooth operation as the trawler edged its way through the lock gates and out into the River Wyre, edging past the notorious Tigers Tail, a sandbank on our starboard side. Many ships ran aground here over the years, especially in fog.

The ship’s telegraph jangled again, and this time the engine really came to life as the chief engineer notched up to full speed. The whole ship shook from stem to stern; huge plumes of black smoke billowed out of the funnel and drifted across the channel.

The engine settled down to a steady rhythm as she picked up speed. There was a great excitement about it all; it was just brilliant. From that moment I was well and truly hooked. This was the start of my life at sea and the beginning of a great journey.

I sailed with my dad between 1946 and 1952. During this time I did fourteen trips on the Comitatus and one trip on the James Lay. Each trip was around fourteen to fifteen days. I’ll tell you about the things I remember happening during these pleasure trips.

We were fortunate that first time. The weather was hot and the sea was calm, just like a millpond. I thought maybe it would be like this all the time, but boy I soon knew different. By the time I left school at fifteen I’d experienced gales and storms more fearsome than I could ever have imagined.

That first trip was like a big adventure. It was all new to us. The weather was calm, the sun shone. We left the dock and entered the River Wyre. We sailed passed the Jubilee Quay were all the small inshore boats were tied up. My mother stood on the seafront to see us off. We waved and shouted until we couldn’t hear what she was saying anymore. We sat on the casing and watched as we sailed out of the river, passing the Isle of Man boat moored up to the quay. We passed the Pharaoh’s Lighthouse, Euston Hotel and Fleetwood Pier. We then made for the Wyre Light.

Dad called us to the bridge to inform Bill and me we were to sleep in his berth. Bill’s friend had a bunk aft with his uncle. The first day was spent exploring the ship and getting to know the crew.

Dad had a few rules about what we could and could not do. The main rule was not to go on deck at all while the nets were being hauled up from the seabed or as they were being lowered away.

We fished on the hundred fathom edge to the north-west of Scotland, all the way to the north-east along the hundred fathom line towards Muckle Flugga, the most northerly point of the British Isles. We were mostly after hake, the prime fish for Fleetwood at that time.

The journey from Fleetwood to Cape Wrath on the north coast of Scotland is one of the finest you can do. The scenery down the west coast and through the Sounds of Mull is breathtaking, especially in late summer when the heather is in full bloom, but even in the depths of winter when the snow covers the hills and glens.

The crew were all good men. The mate, a chap called Nelson Rogers, sailed with my dad for a long time but my favourite by far was the aptly-named Albert Cook, the ship’s cook. He was great, he used to look after us, nothing was too much trouble for him and he was an excellent cook. Every morning Dad sent us aft with a bucket. Albert would fill it with hot water and we’d stand on the after deck to have a strip down wash. When we were done Albert would have a steaming mug of hot tea ready for us.

‘Now lads what do you want for breakfast? How about a couple of boiled eggs?’ he’d ask.

‘Good idea Albert,’ we’d reply.

Around ten o’clock in the morning the stove was littered with pots and pans all boiling away full of spuds, cabbage and other stuff for dinner. This never bothered Albert; he’d just toss three or four eggs into the pan of soup. While the eggs were boiling he would butter a couple of busters (fresh baked bread buns). They were the best. They made for great egg sandwiches!

I’d help Albert in the galley where I could, washing up or peeling spuds. During bad weather I had to stay out of the galley in case anything hot got thrown off the stove. In the afternoons when Albert was having his nap I made sure his coal locker was filled up and the fire didn’t go out.

At the end of the trip Albert baked a dozen busters for me to take home. I also took home pepper. Just after the war things were rationed and pepper was scarce so I’d do my bit to help Mother. Often on the trip home the ships called into Southern Ireland. Lots of things in Southern Ireland were not rationed like at home. It was not unknown for a crew member in need of a new suit to go away in an old one and come home in a brand new one.

Albert was on the Comitatus all the time I sailed with Dad. I can’t recall any other cook being there.

Another crew member I remember well was the deckhand learner Bill Barton, from Wharton just outside Preston. Aged about fifteen, he’d been with my dad for about a year since he left school. Deckhand learners were known as ‘brassys’. This came about because around the turn of the century they’d wear a uniform ashore with brass buttons, similar to that worn by the Merchant Navy. In Grimsby he’d have been known as the decky learner and in Hull as the snacker. Bill and me got on well with him; we’d sit and talk for hours about fishing and all sorts. He was very keen, a good worker always willing to learn.

One trip we went into Londonderry. I believe it was a big naval base at the time. As we steamed up the Lough there where row upon row of German submarines, all captured or surrendered after the Second World War. We sat on the casing watching them go by. As we passed a couple of Royal Navy Frigates Bill jumped up and grabbed my arm, he was very excited.

‘Look! Look!’ he shouted, pointing to one of the ships.

‘My pal’s on her, I’m going to ask Dad if I can go and see him.’

Dad refused, he wanted Bill to take me to the pictures when we went ashore. Bill was very disappointed. After tea I washed in the bucket before Bill and I went ashore.

‘Do you mind if we go round to the Naval base and see if I can see my pal?’ Bill asked.

I was all for it, thinking that I would get on one of the navy ships. On the way we stopped to ask a policeman for directions. I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw he had a gun. When we arrived at the base the guard at the gate also had a gun. I had never seen a real gun before, let alone two in one day!

Bill enquired about his pal at the dockyard gate but we weren’t allowed on the base for security reasons. I was a bit disappointed; I wasn’t going to see the ships after all. The guard asked Bill the name of the ship his friend was on and he contacted the ship by telephone.

‘You’re lucky mate; he’s getting ready to come ashore so if you hang about he’ll be out shortly.’

Twenty minutes later Bill’s pal showed up. I was introduced to him and Bill explained why he had me tagging along.

‘Well I have to be back on board by 22.00 hours so we will go for a couple of pints and catch up,’ Bill’s pal informed us.

My dad thought we were going to the cinema but we were actually going to the pub and I had to promise not to tell. We set off down the street looking for a decent place to go; they all looked a bit rough. Bill decided they wouldn’t be suitable for me. The third one looked quite respectable and after a bit of a discussion it was decided this one would do.

Bill’s pal went in first. Bill started to follow but as he got halfway through the door somebody in the pub started to laugh. Bloody hell it was Dad! Panic stricken I grabbed Bill’s arm.

‘Bill,’ I said in a whisper. ‘Dad’s in there don’t go in.’

By this time his mate had disappeared into the pub. We had to hang around outside until he came out to see where we had got to and we made a quick retreat down the road. That was a bit too close for comfort. Had we gone in my dad would have gone mad, I wouldn’t have been in Bill’s shoes for the world!

The chief engineer (Webby) was with my dad all the time I did pleasure trips. I remember him well and he’d often come to our house when they were in dock. Webby must have been with my dad for about seven years. The second engineer was a chap they called Happy Harry. One trip everybody was running out of tobacco and cigarettes were in short supply. Some of the crew had run out altogether. Happy Harry still had tobacco left, but being the sort of person he was he’d see you gasping rather than give you a cigarette. Harry always saved his tab ends in a tin alongside his bunk, and it was nearly full.

A couple of the deckhands kidded me on to go and pinch them. At first I was a bit reluctant but the deckhands said he had loads of tobacco left. After a bit of persuasion I agreed. Once he was asleep I sneaked into his cabin, took all his tab ends and gave them to the deckies. They rolled them up into fags and shared them out. I must say I felt pretty good about it. After all, Harry had plenty of tobacco left, didn’t he?

The crew was in the pound gutting fish. I was trying to gut a cod that was nearly as big as me but the cod was winning when Albert called out dinner was ready. For some reason my dad did not go for his dinner at 12.00 as he usually did but stayed on the bridge. I was sat in the galley with Albert. I was not allowed to have my dinner till 12.30.

As the crew was having dinner I could hear raised voices in the cabin, some sort of argument going on. ‘Take no notice Jim, they are always falling out about something or other,’ Albert said. At 12.30 the crew was back on the deck. Albert told me to go and get my dinner. I went down to the cabin. As I got to the bottom of the ladder Happy Harry started pointing and shouting at me.

‘You!’ he snarled. ‘You pinched my fags for them bastards on the deck. I saw you sneaking out of my cabin when you thought I was asleep. I’m surprised at you Jim, I didn’t think you’d do a thing like that.’

I could feel myself colouring up, I felt terrible and scared, nobody had ever shouted at me like that before. I was close to tears. With that my dad came down the ladder into the cabin. Bloody hell, now I was in real trouble!

‘What’s going on? What’s all the shouting about?’ said Dad.

Harry told him what I had done; I was expecting the worst, at least a clip around the ear hole. Dad looked at me, winked, then turned and said to Harry, ‘That’s bugger all to what his old man’s done in the past. Don’t worry about it Harry, come on the bridge later and I’ll give you some tobacco.’ My dad never mentioned it to me again, I don’t know if he told the crew off. If he did they never said.

I attended three schools in Fleetwood, Flake Fleet Infants School, Chaucer Road Junior School and Bailey Secondary Modern School (nicknamed Bailey Borstal). While I was at Chaucer Road School the Fleetwood trawler Goth went missing. There were rumours going around that something was wrong, and a couple lads were off that day. It wasn’t until after school we read in the Fleetwood Gazette that the she’d gone missing.

At 147ft, she was built in 1925 by Cook, Welton & Gemmel of Hull and Beverly for the Hellyer Bros Ltd of Hull. At the outbreak of the Second World War she was taken over by the Royal Navy for minesweeping. After the war she was sold to the Ocean Steam Fishing Company Ltd of Hull. Not until 1946 was she sold to the Wyre Steam Trawling Company and transferred to Fleetwood.

Her last report on 16 December 1948 stated she was making for shelter at Adalvik on the north-west coast of Iceland in severe weather. Tragically she disappeared with the loss of all twenty-one crew. The last message received from her was picked up by the Grimsby trawler Lincoln City, stating her intentions to seek shelter. Nothing more was heard from her.

On 15 November 1997 the Icelandic trawler Helga (RE 49) trawled up a ship’s funnel in her net while fishing north-west of Halo, on the north-west coast of Iceland. The funnel was taken into Reykjavik; it was later identified as belonging to the Goth. The funnel has now been returned to Fleetwood where the relatives have preserved it as a memorial to the crew.

It was always terribly sad when a trawler went missing. Fishing communities were very close; everyone knew someone who had a relative or friend on a ship and everyone rallied round to help the families of the lost men.

By the time I was ten years old, I had already done five trips to sea with my dad on the Comitatus. One morning, just after breakfast, we were hauling our gear. Working off the west coast of the Shetland Islands in deep water we had 900 fathoms of warp out; we were fishing for hake and we still had about 75 fathoms of warp to heave up. It was then that we saw a large patch of the sea turning a blue-green colour with lots of bubbles appearing on the surface.

‘Look at that,’ shouted one of the crew. They knew what was coming next. Suddenly the net burst to the surface. It shot up out of the sea like a whale leaping out of the water – a huge haul of fish. The end of the net stuck out the water like a giant haystack. It stayed like that for a few minutes then slowly rolled over and spread out over the sea like a giant sausage.

The winch was slowed as we tried to heave the net slowly to the ship’s side. Too much speed would’ve seen the net burst open and the fish lost, about 12 to 15 tons of it! Had the weather been bad we’d certainly have lost the lot. Fortunately the weather was fine but with long heavy Atlantic swells rolling along. We could see fish escaping; somewhere there was a hole in the net. After a struggle we got enough net on board to get a rope round it and heave all the fish down into the net.

I was very excited. I’d not seen so much fish in one haul but it looked as though we were going to lose most of it. The hole in the net was getting bigger by the minute and the sea was littered with fish floating away. Suddenly Dad jumped onto the deck, tied a rope around his waist, grabbed a mending needle and gave the end of the rope to a deckhand. ‘Don’t you dare let go of that,’ he shouted, before jumping over the side onto the net and gingerly making his way along the back as I looked on in horror. I couldn’t believe what he was doing. There was just about enough buoyancy in the fish to stop him sinking but I was petrified he was going to fall into the sea.

Once he’d reached the hole he did a quick repair and made his way back, more than once he nearly fell off. My heart was in my mouth and I was relieved when he was back on board.

When we’d got the fish on board the deck was absolutely full. We got about sixty baskets of hake – an excellent haul by any standard. The rest were coalfish which were no good. We gutted the coalfish to get the livers out for cod liver oil. In Fleetwood ‘coalies’ as we called them did not sell well so only the very best were saved for market. I thought my dad was a hero going out on that net, but after I’d had a few more years’ experience I realised it had been a bloody stupid thing to do. I probably did things that were even more stupid! But that’s a fisherman’s life.

A couple of days later we were hauling the gear. I was sat on the casing watching the bosun working on the after trawl door. As he tried to put the chain on the door it swung inboard, trapping his arm. He screamed out in pain and fell to the deck. I was horrified at the amount of blood running down his arm onto the deck. I was shaking and felt sick, not knowing what to do. Dad came out of the wheelhouse and told me to get out of the way. I waited anxiously in the wheelhouse as they took him aft to assess the damage. Dad came and told me his arm was in a bad way and we’d be taking him to hospital in Oban.

One trip I was fooling around on the deck just passing time away with the deckhand on watch. He showed me how to mend nets and splice a rope. He was going to put some coal on the fire down in the forecastle so I went with him.

We went down below, he stoked the fire and we sat talking. He showed me how good he was at sticking his knife into the bulkhead. The rest of the crew was in their bunks trying to get some sleep. One of them got a bit pissed off with the noise the deckhand was making with his knife. A row followed and the deckhand was going to thump him. A voice from another bunk shouted, ‘If you two don’t make less noise, I’ll get out and thump the pair of you, now f**k off back on the deck.’

With that the two deckhands were up on deck squaring up to each other. Dad was on the bridge. On hearing the commotion he came out on deck. I thought he was going stop them, but no, instead he made them take all the deck boards up and put them out of the way then told them to get on with it, but to stop when he said. There was a bit of pushing and shoving, half a dozen blows followed, one had a cut lip and the other a black eye. Then Dad stepped in and stopped it. He made them shake hands and it was all over. The boards were put back and the ship returned to normal.

As Dad went back to the bridge he turned to me and said, ‘That was nothing to do with you was it?’

‘No Dad,’ I replied trying to look innocent.

‘If they’re going to fight, let them, or they’ll be at it the entire trip. If you let them fight they will become best friends,’ he informed me.

And he was right, they did.

That trip we had a cat on board. Any stray animals we found at home always finished up at sea with Dad. This cat was as nutty as a fruitcake. It didn’t matter how bad the weather was, he’d charge around the ship chasing seagulls he hadn’t a hope in hell’s chance of catching. He drove the crew mad by running along the ship’s rail and straight up the rigging till he got to the top. Once at the top he would hang on and cry until one of the crew climbed up to get him down. He was threatened with a watery grave on more than one occasion.

On one trip a couple of deckhands brought some dye with them and threatened to dye the cat blue – Dad said just try, and that was enough to put them off. Instead they got buckets full of different coloured dyes and spent the rest of the day catching fulmars and dying them instead. There were red, blue and green fulmars flying around for the rest of the trip. Dad didn’t think a lot of it and sacked the pair of them when we docked.

At home one winter we had severe frost and snow. At the back of our house was an outbuilding with a coalhouse and washhouse. One night I was told to go and get some coal for the fire. It was dark and snowing. I opened the coalhouse door. There were no lights inside; it was pitch black so I had to shovel the coal into the bucket by feel. I started poking about with my shovel looking for the coal. I kept poking something heavy, it didn’t feel like coal. I put my hand out and touched the stuff. To my horror it was warm and it moved. I dropped the shovel and ran screaming into the house, face as white as a sheet. I was convinced I had found a body.

What made it worse was that about a year earlier a young girl had been murdered and her body had been thrown into a manhole in the road just round the corner from where we lived. The culprit had never been caught. I thought he’d come back, I was terrified. I ran into the house yelling to Mother that there was a body in the coalhouse. Dad was away at sea so she went next door to get the neighbour. He came round with a torch and we went out to the coalhouse. Standing well back while he went in, we could hear him talking to someone.

‘Come on then, no need to be afraid, no one’s going to hurt you now, we’ll look after you,’ we heard him say. We thought he would emerge with a body; instead he came out carrying a big black dog. Poor thing was in a terrible state, trembling, frightened, cold and very close to death. We got an old blanket out and laid him by the fire. We tried to feed him but he was too weak and feeble. Before we went to bed my mother built up the fire to keep him warm during the night. Dad was due home the next day and he’d know what to do.

Next morning the dog was still alive and looked a bit brighter. When Dad got home the first thing he did was give him a saucer of milk with brandy in it. He wasn’t very good for a week or so but gradually got his strength back and made a full recovery. Dad took the dog, who we christened Blackie, to sea with him.

My next trip with Dad was early April (Easter holidays) that year. The weather was poor for the first four or five days. Wind was NW force 6 to 7, only just fishable. I loved the bad weather. I could stand on the bridge all day long just watching the seas rolling along, the bigger the better. There was something majestic and frightening about them. The crew used to tell me I was crazy. ‘You won’t think that when you’ve got to work in it,’ they would say. But I’d just laugh.

A few days later the weather turned really bad. Within an hour the wind increased from force 6 to 7 to force 8 to 9 gusting to force 10. The crew was called upon to get the gear on board as quickly as possible. I was in the wheelhouse with Dad; he told me to keep on the port side out of the way. The mate and a deckhand went to the winch and started heaving the warps to bring the net up. The wind was on the port bow. When there was about 25 fathoms of warp to heave up the winch was stopped. Dad put the wheel over to starboard. The ship came slowly around. By this time the rest of the crew was on deck ready. When the ship was in position with the wind on the starboard quarter the engines were stopped. The order was given to heave on the winch.

The first thing out of the water was the forward trawl door; it was chained up and disconnected from the rest of the gear. The net was already on top of the water, the wind was screaming. The crew had to bend forward into the wind to stop them being blown over. Hailstones and heavy spray driven on by 50mph winds peppered their faces like icy needles. With eyes half closed, squinting to see, the crew went about their work without a word. No one spoke, every man knew exactly what to do, and did it. This is when teamwork comes into its own. And there’s no better teamwork than a trawler crew getting the net aboard in such conditions.

When both trawler doors were safely in the gallows and unclipped from the warp the net was heaved to the ship’s side. I was hanging on to stop myself falling over. Suddenly Dad dropped the bridge window! He shouted at the men: ‘Look out for water! Get out of the way!’

Almost immediately a huge sea hit us. The sea crashed against the side of the ship, sending heavy sprays of water high into the air and through the bridge windows, filling the wheelhouse. I was soaked through. The ship was now laid over to starboard.

We were awash, the decks were flooded. I looked out of the window at the foredeck and it was full of water. Two of the crew had been swept from the starboard side onto the foredeck. They were struggling in the water, desperately trying to grab hold of something, anything, to regain their balance and get stood up. One was bleeding from his forehead. Suddenly I was scared.

Bloody hell, I’d seen bad weather before but never like this. I was petrified. Where were the rest of the crew?

Dad shouted at me to get down into the berth and out of the way. I didn’t need telling twice. Blackie was down there. He lay on the mat, head on his paws. Half asleep he looked up at me as if wondering what all fuss was about. I got out of my wet clothes, dried myself off as best I could and sat on the bunk trying not to fall out.

There was a lot of commotion going on; men were shouting and the winch rattled as they struggled to get the gear aboard. I could hear Dad shouting orders from the bridge. After about an hour and a half I heard the ship’s telegraph. The engine started up and the ship came alive. The old girl pitched and tossed as she struggled to get her head into the wind. Once we were up head to wind things settled down a bit though we were still rolling and tumbling about.

I heard the wheelhouse door open and voices on the bridge. I went up the steps to the wheelhouse but as I popped my head out the hatch I was told to go back down and stay there.

A bit later Dad came down followed by the deckhand, the one who’d cut his forehead.

‘Are you OK Jim?’ Dad asked me.

‘Yes,’ I told him.

He dragged the medicine chest out. The deckhand sat on the seat locker while my dad sorted him out. He had a bad cut just above his right eye which was closed and puffed up. Dad said it could’ve done with a couple of stitches but in view of the weather we wouldn’t be able to get in to land until the weather eased off.

When he’d gone Dad told me not to go into the wheelhouse as the weather was now reaching hurricane force and it was too dangerous. I could hear the wind howling and the seas crashing against the front of the bridge. I had no wish to go anywhere! Little did I realise I’d be down here for the next four or five days. Food was stew and sandwiches and all the tea I could drink. My toilet was a bucket. The dog was well trained though. He’d walk the berth, looking up at the hatch. I’d shout to Dad and he’d take him up onto the wheelhouse veranda and tie a rope around him in case he fell off.

The time was endless as I’d nothing to do. I’d read everything that was down in the berth. I was bored stiff. I listened to the radio, although most of the time it was tuned in to other trawlers keeping in contact with each other.

The weather was relentless. We were rolling and tumbling about. I was bruised and aching all over from being knocked about and trying not to fall out of my bunk. I decided to get some sleep so I pulled the blanket over me; suddenly I awoke with a start. I must have dozed off. There was a loud crash as a huge sea hit us. The ship rolled violently over to starboard, it seemed she was going to roll right over. I was thrown against the side of the bunk. Even the dog jumped up and started barking. Now that did scare me! On the bridge I could hear shouting, the crashing of breaking glass, the splintering of wood as the wheelhouse windows caved in. The sea rushed into the bridge – it was full of water. There was only one way for the water to go: down the hatch and into the berth.

The water came down in such a huge mass it compressed the air in the berth. The pressure was so great it hurt my ears. I put my hands over them to try and stop it. As the flow of water eased the pressure became less, as did the pain. Now the berth was half full of water. The poor old dog was floundering about. He managed to scramble onto the seat locker and from there he made a great leap and landed in the bunk alongside me. I don’t know who was more scared, the dog or me!

The ship was still laid over to starboard, I really thought she was about to sink. I made one leap from the bunk to the ladder. I had to get out of there. I missed the ladder and fell backward into the water. Panicking, I scrambling about until I got my grip. I climbed up, poking my head through the hatch.

‘Are we sinking?’ I shouted to Dad.

‘No!’ he replied. ‘Get back down the berth, I’ll be there in a bit.’

I managed to have a quick look round the bridge. It was total devastation. All the windows at the front had been smashed in. Wood and glass was everywhere and in a corner of the bridge sat one of the crew, his face covered in blood. I told Dad the berth was half full of water.

‘Don’t worry about that,’ he said. ‘We’ll sort it in a bit.’

I noticed he’d cut his hand, it looked a right mess. I’d been convinced we were sinking but the ship was now more or less back on an even keel. The crew’s injuries were not as serious as they looked. The damage to the bridge, however, was quite serious. The windows had been completely taken out and the plates at the front of the bridge had been buckled. There was damage around the deck and we’d lost a few deck boards. We’d been extremely fortunate really. The first job was to secure the bridge by nailing boards and canvas across the gaps where the windows had been. The crew then set about bailing out the berth and getting things dried out.

Twenty-four hours later we were steaming towards Cape Wrath, homeward bound. The sun was shining and it was a glorious day. The weather was down to a force 5 or 6, although there was still a lot of swell. It’s hard to imagine that a day earlier we had been in weather so violent I’d wondered if we were ever going to get out of it. On the way home Dad asked if I’d be back to sea again after this.

‘Just try and stop me,’ I said.

‘Then you are crazier than I thought,’ he replied.

But I think he was pleased with my reply.

That was my last trip on the Comitatus as she was sold to a Grimsby firm that year. I felt quite sad as over the years I’d got to know her like an old friend. I spent many happy hours on her and got to know a lot of good shipmates.

I did one more pleasure trip with my dad in the summer of 1952 on the trawler James Lay, but it was not the same. The James Lay stopped for a fit-out and Dad went mate on the Reptonion to Iceland. That ship changed all our lives.

My dad was so taken with fishing at Iceland that on returning to port he asked the firm if he could go Icelandic fishing permanently. They refused. He was one of their top hake skippers. He was told to go back in the James Lay or they wouldn’t give him another ship. So he left Fleetwood, joined Northern Trawlers in Grimsby and went mate on the trawler Northern Isle.