Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Vertebrate Digital

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

Mountaintops have long been seen as sacred places, home to gods and dreams. In one climbing year Peter Boardman visited three very different sacred mountains. He began on the South Face of the Carstensz Pyramid in New Guinea. This is the highest point between the Andes and the Himalaya, and one of the most inaccessible, rising above thick jungle inhabited by warring Stone Age tribes.During the spring Boardman made a four-man, oxygen-free attempt on the world's third highest peak, Kangchenjunga. Hurricane-force winds beat back their first two bids on the unclimbed North Ridge, but they eventually stood within feet of the summit – leaving the final few yards untrodden in deference to the inhabiting deity. In October, he climbed the mountain most sacred to the Sherpas: the twin-summited Gauri Sankar. Renowned for its technical difficulty and spectacular profile, it is aptly dubbed the Eiger of the Himalaya and Boardman's first ascent took a gruelling twenty-three days.Three sacred mountains, three very different expeditions, all superbly captured by Boardman in Sacred Summits, his second book, first published shortly after his death in 1982. Combining the excitement of extreme climbing with acute observation of life in the mountains, this is an amusing, dramatic, poignant and thought-provoking book.Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker died on Everest in 1982, whilst attempting a new and unclimbed line. Both men were superb mountaineers and talented writers. Their literary legacy lives on through the Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature, established by family and friends in 1983 and presented annually to the author or co-authors of an original work which has made an outstanding contribution to mountain literature.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 529

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Sacred Summits

Kangchenjunga, the Carstensz Pyramid and Gauri Sankar

Sacred Summits

Kangchenjunga, the Carstensz Pyramid and Gauri Sankar

Peter Boardman

www.v-publishing.co.uk

Contents

Foreword by Chris Bonington ‘A Great Partnership’

Part One Snow Mountains Of New Guinea

Chapter One Sacred Summits

Chapter Two Troubled Paradise

Chapter Three Amakane

Chapter Four Carstensz

Chapter Five Dugundugu

Chapter Six An Impossible Dream

Chapter Seven Back From The Stone Age

Part Two Kangchenjunga

Chapter Eight Spring

Chapter Nine Séracs

Chapter Ten The Wall

Chapter Eleven Ordeal By Storm

Chapter Twelve Before Dawn

Chapter Thirteen Softly To The Untrodden Summit

Chapter Fourteen Down Wind

Chapter Fifteen Summer

Part Three Gauri Sankar

Chapter Sixteen First Time

Chapter Seventeen Knight Moves

Chapter Eighteen Borderline

Chapter Nineteen Cliffs Of Fall

Chapter Twenty Final Choice

Chapter Twenty One Tseringma

Chapter Twenty Two Autumn … To Earth With Love

Chapter Twenty Three Winter

Acknowledgements

Foreword

A Great Partnership

Chris Bonington

It was 15 May 1982 at Advance Base on the north side of Everest. It’s a bleak place. The tents were pitched on a moraine the debris of an expedition in its end stage scattered over the rocks. Pete and Joe fussed around with final preparations, packing their rucksacks and putting in a few last minute luxuries. Then suddenly they were ready, crampons on, rope tied, set to go. I think we were all trying to underplay the moment.

‘See you in a few days.’

‘We’ll call you tonight at six.’

They set off, plodding up the ice slope beyond the camp through flurries of wind-driven snow. Two days later, in the fading light of a cold dusk, Adrian Gordon and I were watching their progress high on the North East Ridge through our telescope. Two tiny figures on the crest outlined against the golden sky of the late evening, moving painfully slowly, one at a time. Was it because of the difficulty or the extreme altitude, for they must have been at approximately, 27,000 feet (8230 metres)?

Gradually they disappeared from sight behind the jagged tooth of the Second Pinnacle. They never appeared again, although Peter’s body was discovered by members of a Russian/Japanese expedition in the spring of 1992, just beyond where we had last seen them. It was as if he had lain down in the snow, gone to sleep and never woken. We shall probably never know just what happened in those days around 17 May, but in that final push to complete the unclimbed section of the North East Ridge of Everest, we lost two very special friends and a unique climbing partnership whose breadth of talent went far beyond mountaineering. Their ability as writers is amply demonstrated in their books.

My initial encounter with Peter was in 1975 when I was recruiting for the expedition to the South West Face of Everest. I was impressed by his maturity at the age of 23, yet this was combined with a real sense of fun and a touch of ‘the little boy lost’ manner, which he could use with devastating effect to get his own way. In addition, he was both physically and intellectually talented. He was a very strong natural climber and behind that diffident, easy-going manner had a personal drive and unwavering sense of purpose. He also had a love of the mountains and the ability to express it in writing. He was the youngest member of the Everest team and went to the top with our Sherpa sirdar, Pertemba, making the second complete ascent of the previously unclimbed South West Face.

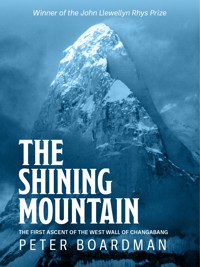

As National Officer of the BMC, he proved a diplomat and a good committee man. After Dougal Haston’s death in an avalanche in Switzerland, he took over Dougal’s International School of Mountaineering in Leysin. He went on to climb the sheer West Face of Changabang with Joe Tasker, which was the start of their climbing partnership. It was a remarkable achievement, in stark contrast to the huge expedition we had had on Everest. On Changabang there had just been Pete and Joe. They had planned to climb it alpine-style, bivouacking in hammocks on the face, but it had been too cold, too great a strain at altitude, and they had resorted to siege tactics. Yet even this demanded huge reserves of determination and endurance. The climb, in 1976, was probably technically the hardest that had been completed in the Himalaya at that time, and Pete describes their struggles in his first book, The Shining Mountain, which won the John Llewelyn Rhys Prize in 1979.

Pete packed a wealth of varied climbing next few years. In 1978 both he and Joe joined me on K2. We attempted the West Ridge but abandoned it comparatively low down after Nick Estcourt was killed in an avalanche. In early 1979 Pete reached the summit of the Carstensz Pyramid, in New Guinea, with his future wife, Hilary, just before going to Kangchenjunga (the world’s third highest mountain) with Joe, and Doug Scott and Georges Bettembourg That same autumn he led a small and comparatively another team on a very bold ascent of the South Summit of Gauri Sankar.

The following year he returned to K2 with Joe, Doug and Dick Renshaw. They first attempted the West Ridge, the route that we had tried in 1978, but abandoned this a couple of hundred metres higher than our previous high point. Doug Scott returned home but the other three made two very determined assaults on the Abruzzi Spur, getting to within 600 metres of the summit before being avalanched off on their first effort, and beaten by bad weather on a subsequent foray. Two years later Pete and Joe, with Alan Rouse, joined me on Kongur, at the time the third-highest unclimbed peak in the world. It proved a long drawn out, exacting expedition.

Joe Tasker was very different to Peter, both in appearance and personality. This perhaps contributed to the strength of their partnership. While Pete appeared to be easy going and relaxed, Joe was very much more intense, even abrasive. He came from a large Roman Catholic family on Teesside and went to a seminary at the age of 13 to train for the priesthood, but at the age of 18 he had begun to have serious doubts about his vocation and went to study sociology at Manchester University. Inevitably, his period at the seminary left its mark. Joe had a built-in reserve that was difficult to penetrate but, at the same time, he had an analytical, questioning mind. He rarely accepted an easy answer and kept going at a point until satisfied that it had been answered in full.

In their climbing relationship had a jokey yet competitive tension in which neither of them being wished to be the first to admit weakness or to suggest retreat. It was a trait that not only contributed to their drive but could also cause them to push themselves to the limit.

Joe had served an impressive alpine apprenticeship in the early ’seventies when, with Dick Renshaw, they worked through some of the hardest climbs in the Alps, both in summer and winter. These included the first British ascent (one of the very few ever ascents) of the formidable and very remote East Face of the Grandes Jorasses. In addition they made the first British winter ascent of the North Wall of the Eiger. With Renshaw he went on to climb, in alpine-style, the South Ridge of Dunagiri. It was a bold ascent by any standards, outstandingly so for a first Himalayan expedition. Dick was badly frostbitten and this led to Joe inviting Pete to join him on Changabang the start of their climbing partnership.

On our K2 expedition in 1978, I had barely had the chance to get to know Joe well, but I remember bring exasperated by his constant questioning of decisions, particularly while we were organising the expedition. At the time I felt he was a real barrack-room lawyer but, on reflection, realised that he probably found my approach equally exasperating. We climbed together throughout the 1981 Kongur expedition and I came to know him much better, to find that under that tough outer shell there was a very warm heart. Prior to that, in the winter of 1980-81, he went to Everest with a strong British expedition to attempt the West Ridge. He told the story in his first book, Everest the Cruel Way.

Our 1982 expedition to Everest’s North East Ridge was a huge challenge but our team was one of the happiest and most closely united of any trip I have been on. There were only six in the party and just four of us, Joe, Pete, Dick Renshaw and I, were planning to tackle the route. Charlie Clarke and Adrian Gordon were there in support going no further than Advance Base. However, there was a sense of shared values, affection and respect, that grew stronger through adversity, as we came to realise just how vast was the undertaking our small team was committed to.

It remained through those harsh anxious days of growing awareness of disaster, after Pete and Joe went out of sight behind the Second Pinnacle, to our final acceptance that there was no longer any hope.

Yet when Pete and Joe set out for that final push on 17 May I had every confidence that they would cross the Pinnacles and reach the upper part of the North Ridge of Everest, even if they were unable to continue to the top. Their deaths, quite apart from the deep feeling of bereavement at the loss of good friends, also gives that sense of frustration because they still had so much to offer in their development, both in mountaineering and creative terms.

Chris Bonington

Caldbeck, September 1994

Peter Boardman.

Joe Tasker.

THE MOST-SACRED MOUNTAIN

Space, and the twelve clean winds of heaven

And this sharp exultation, like a cry, after the slow six thousand

feet of climbing!

This is Tai Shan, the beautiful, the most holy.

Below my feet the foot-hills nestle, brown with flecks of green;

and lower down the flat brown plain, the floor of earth,

stretches away to blue infinity.

Beside me in this airy space the temple roofs cut their slow

curves

against the sky,

And one black bird circles above the void.

Space, and the twelve clean winds are here;

And with them broods eternity – a swift, white peace, a presence

manifest.

But I shall go down from this airy space, this swift white peace,

this stinging exultation;

And time will close about me, and my soul stir to the rhythm

of the daily round.

Yet, having known, life will not press so close, and always I

shall feel time ravel thin about me;

For once I stood

In the white windy presence of eternity.

Eunice Tietjens

PART ONE

SNOW MOUNTAINS OF NEW GUINEA

Chapter ONE

SACRED SUMMITS

30th November-5th December 1978

It was the last day of November. It was a quiet uncluttered day, and over ten years since I had last stood on this mountain. Then I saw only an exciting, jagged blur of sweeping snow and rock shimmering in summer heat, and dark hazy valleys twisting away below and beyond. Now I saw with different eyes, with a sense of intimacy, almost possession.

Each mountain I could see from the Aiguille de Tour held a different adventure shared with a different friend. Memories, trivial and moving surged inside me. Time had not diminished them. I saw tiny figures of the past picking slowly across the snow and heard their voices. Among those mountains I had found a kingdom that had seemed infinite. Although a newcomer, I had felt apart from the tourists. I was one of the climbers who lived in the woods. First I had climbed urgently, to escape, rather than to search for something that I loved – the absorbed, animal struggle up the crack at the top of the Aiguille de Purtscheller when I was seventeen, the storm on Mont Blanc, when the snow covered our tracks, the lightning shocks on the Gervasutti Pillar, dawn on the Frendo Spur, and the heights of freedom and happiness, emerging into the evening above the precipices of the Dru. And more gentle, recent memories of just a few months before, a walk across the Trient Glacier with my mother and father, and a traverse with Hilary of the Aiguilles d’Orées, the needles of gold.

Different memories of early mad rushes to fill up my postcards home with lists of routes I had climbed, to tick off the hardest routes as if they were a shopping list, and of later calm, when I discovered the long ridges and filled out the landscape within my mind, seeing these mountains from all sides, in all weathers, and understanding them.

Many people know these mountains – some grow to love them, others try to rape them.

It was cold, and humanity huddled in their oases – dark smudges below the thrusting white snows of winter’s defence. The ski season had not yet started and the new, packaged human colonies above the snow line had not yet awakened. Man the exploiter and nature for some moments stood apart.

In the east a distant spire rose from a crown of rock. The Matterhorn. Eight years earlier, and again three months ago, I had stood on its summit. Little more than a century ago, the natives of its surrounding valleys felt an invisible cordon drawn around it. To them the Matterhorn was not only the highest mountain in the Alps, but in the world. They spoke of a ruined city on its summit wherein spirits dwelt; and if you laughed, they gravely shook their heads. To them the mountains were to be feared and suspected as haunts of monsters, wizards and crabbed goblins – and the devil. Something had gone wrong. In earlier times the Matterhorn, the Alps and the trees, rocks and springs of Europe were loved and respected as sacred places. Man had felt his links with them. But then he had broken with this heritage and had buried this delicate magic of life.

I thought of another mountain with a Matterhorn shape, thousands of miles away in the Himalayas. ‘Menlungtse, Menlungtse looks like that, I must look at the photographs.’ The wind veered beneath the cold dark blue sky and I turned my back. There were the tiny rock spires above Leysin, where I lived. And the sun swung down to the west, picking out the deep line of my tracks etched across the glacier below. Shadows grew on the mountain and a great silence was descending too. I knew the mountain, earth set upon earth, would remain silent, long after I had stopped. For some moments I listened, with a still open soul, until I had to turn from a surging feeling of love, before it overwhelmed me. Dear old planet, stay awhile, wait for me. Now I had to go down also.

Four days later she sat next to me in the car. A quick ready shy smile behind a cupped hand and an uncertain, beautiful voice – and we were going on an adventure together! We wound through the ground-hugging fog of the Jura, the headlights beaming a moving wall of white.

We curled out of the mist, and on to the plains of France. The car winged like a bird through cold night air past snow-covered fields, following the arrow of the autoroute to Paris. Hilary’s face was softened by the darkness and she was wrapped in her own silence.

The headlong rush of the car brought plans juggling in my head. Two expeditions to the Himalayas were projected for the coming year. In the spring there would be Kangchenjunga – the arrangements had been made with a casual air in a pub a month before. To attempt this, the third-highest mountain in the world, four of us would leave for Nepal in March. Then, in the autumn, I would return again to the Himalayas to attempt Gauri Sankar, the finest unclimbed mountain in the world. And in between these highlights, I would have to make some money. Peaks in Nepal have to be booked many months before you can approach and attempt them, and my life was booked up in advance. I was on a conveyor belt, carrying me from one booked peak to another. In my mind I tried to stem the rush of these pre-determined commitments and to think clearly, but stopped at the question ‘Why on earth should I fling myself into all this? What was the rush?’ I could not answer. A tiny, not-yet-drowned part of me stood helplessly as the flotsam crashed past, squeaking, ‘I’d rather not,’ and ‘If you don’t mind,’ and ‘Help!’ like Alice wallowing about in the pool of her own tears.

The Snow Mountains of New Guinea, the mountains of the Stone Age, however, could not be booked and that was where Hilary and I were going now. Not only were we uncertain about reaching their summits but also uncertain that we would even reach their feet.

In Paris, our friend Marie, a painter, said: ‘Mountain climbing, brutal dangerous mountain climbing is too extreme for me to express. But exploration I can understand. You go not for the people, not for the mountains, but for them together. Climbers, they are lucky in that they have mountains to justify journeys across continents.’

Projects, hopes and resolutions jostled in my brain, clamouring for attention. I could not wander from day to day. I had to plan. The Victorian explorer Tom Longstaff always warned his protégés: ‘Once a man has found the road, he can never keep away for long.’ The germ of travel was working inside me like a relapsing fever.

Chapter Two

TROUBLED PARADISE

6th-22nd December 1978

‘We saw very high mountains white with snow in many places which certainly is strange for mountains so near the equator.’ So wrote Jan Carstensz the Dutch navigator, in 1623 as he sailed on the Arafura Sea, between New Guinea and Australia. Snow mountains in New Guinea? Nobody believed him when he returned to Holland. Centuries later the mysteries of these mountains are still being unravelled. At 16,020 feet (4,883 metres.), the highest peak in South East Asia and the highest point in the range has been named after him, the Carstensz Pyramid.

At some time during their careers, all great explorers are monomaniacs – imagination seized, they identify with a mountain, a pole, a blank on the map, then gather will and energy together to fling themselves in effort after effort towards it. The history of exploration is punctuated with the intensity of such relationships: Scott and the South Pole, Mallory and Everest, Shipton and Tilman and Nanda Devi, Bauer and Kangchenjunga, Herzog and Annapurna. The Snow Mountains of New Guinea have obsessed two great explorers – A.F.R. Wollaston, who tried to reach the mountains from the south early this century, and the devoted and energetic New Zealander, Philip Temple who, in 1961, became the first explorer to approach from the north. Both were fascinated by the unique isolation of these mountains.

However, even in the late 1970s, very little was known about the Snow Mountains in the mountaineering world. The allure that had attracted Wollaston and Temple was still there. These mountains were far away from the main mountaineering regions, they were difficult of access, usually covered in cloud, and rose from a strange uninhabited plateau surrounded by jungle, swamp and tribes of primitive peoples still living in the Stone Age. In the autumn of 1976, these isolated mountains had slowly begun to take hold of my imagination.

Whilst Joe Tasker and I were climbing the West Wall of Changabang in the Himalayas that autumn, we often talked, during the forty days of cold struggle it took to climb the mountain, about how it would be so much more pleasant to go to a mountain range in the tropics. We longed for the excitement of travel in an unknown land as a change from the lonely black and white struggle of extreme climbing. But it would have to be the right place, with the right person. Half in fun, we made a pact to find two young ladies and go to New Guinea together.

I was lucky, I found the other half of my expedition very quickly. The first public slide-show I gave about Changabang was at Belper High School. The lecture was organised by Hilary Collins, who ran the school’s Outdoor Activities Department. We had met before in 1974, when she attended a course on which I was an instructor at Glenmore Lodge in the Cairngorms. Not long after the lecture we went rock climbing together for the first time, at the Tors in New Mills in Derbyshire. I fell off, clutching a large flake of rock that had come away with my weight. Hilary managed to stop me with the rope after I had fallen thirty feet – a good achievement considering she was only two thirds my weight, and I had nearly hit the ground. It boded well for our relationship. Over the New Year of 1976-77 we went climbing together again in Torridon in North West Scotland. All the girls interested in mountaineering I had met previously seemed either aggressively fanatical, or obscenely healthy, noisy, strong, rosy-cheeked types, inseparable from their anoraks and bobble caps. Hilary was different, and we shared a passion for mountains rather than climbing for competition or health. She had a common-sense, hard working practicality that I lacked. We were compatible. She was talking about going on a trip to the Himalayas when I suggested she came to New Guinea with me. She agreed. Then she started a new job, teaching geography and biology at a private school in Switzerland.

On the 9th January, 1977, I began writing a lot of letters – to Papua New Guinea, Australia, Indonesia, Hong Kong, America, West Germany and Holland, with the intention of following up all leads and of piecing together, like a jigsaw, a picture of the Snow Mountains of New Guinea. I devoured all expedition reports and all the books I could find on the area: Pygmies and Papuans by A.F.R. Wollaston, Nawok! by Philip Temple, I Come From the Stone Age by Heinrich Harrer and Equatorial Glaciers of New Guinea by Melbourne University. I also read many evangelical books by American Fundamentalist Protestant missionaries, describing their work in the highlands around the mountain. Unfortunately, the most comprehensive books were written in Dutch, including the tantalising To the Eternal Snow of the Tropical Netherlands by Dr A.H. Colijn. This book described the 1936 Dutch expedition to the mountains and had very useful aerial photographs. All this research was immensely satisfying. New Guinea was completely outside my previous expedition experience, and every piece of information I gleaned and stored was, for me, a little inroad into a dark unknown.

On 17th January, Dougal Haston, with whom I had climbed on Everest, was killed in an avalanche whilst skiing above the village of Leysin in Switzerland. The mountaineering politics I was involved in at the time, in my work for the British Mountaineering Council, suddenly seemed petty when I heard the news. I went to Dougal’s funeral. By coincidence, the school where Hilary was working was in the next valley, and she was able to meet me at the station in Leysin. The service, the coffin, the grave, the blue sky, deep snow and the mountains, and my walk away, hand in hand with Hilary beneath the tall trees, all combined to make one of the saddest, most moving days of my life. I had come as a pilgrim, to reaffirm a faith in extreme mountaineering, but felt only doubt. Many people said that Dougal had been doomed — that he was an Ahab after a White Whale, that his life had a restless, fanatic pace, and that he had been bound, sooner or later, to over-reach himself. To me he had seemed indestructible, and his death was a sudden shock. Nevertheless, our New Guinea plans were a comfort, for they were a step off the conveyor belt of a career of a professional high-altitude mountain gladiator, and a step towards a wider emotional development.

At Easter we met Jack Baines, the leader of RAF Valley Mountain Rescue team in North Wales. Jack had been to the Snow Mountains in 1972. An effusive talker, he was positively garrulous about New Guinea. It had been the greatest experience of his life. He brought seventeen hours of tape recordings and, as he bubbled a commentary, his enthusiasm caught us and we absorbed his every word like blotting paper. Jack kindled in us a fire of enthusiasm for the Snow Mountains that was to burn steadily for the many frustrating months that were to pass before we finally saw them. We planned our departure for July 1977 and, as time passed, our New Guinea file became thicker. The mountains were appearing in my dreams. However, I would never really be able to believe in their existence until I saw them for myself.

New Guinea is divided into two halves – Irian Jaya and Papua New Guinea – by the 1410 line of longitude. The highest mountains, and the only mountains with glaciers, lie in the western half, Irian Jaya, which used to be a Dutch colony but is now controlled by Indonesia. The whole of the area is under military control and previous expeditions advised that we would have to keep a very low profile and travel as tourists, rather than as an ‘official’ mountaineering expedition. I wrote to the British Embassy in Jakarta asking about access to Irian, and within a few days the whole situation was taken out of my hands. One of the staff at the Embassy, coincidentally, was organising an eleven-man joint Indonesian-British expedition to the mountains at the same time, and Hilary and I were embraced into their ranks. The Deputy Chief of the Armed Forces of Indonesia had agreed to be the expedition’s patron. Since most of the positions of power in Indonesia are held by army officers, it seemed that all our problems were solved.

On the 6th June, however, our expedition was cancelled. Apparently there had been some trouble in Irian Java, and outsiders were not welcome. A proposed visit by the American Ambassador to the copper mine south of the mountains had been cancelled. Most of the missionaries in the interior had been flown out.

Quickly we changed our plans and spent a month climbing in Kenya and Tanzania, reaching the summits of Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro. This, however, was mere ‘tropical training’, compared to our determination to go to the Snow Mountains of New Guinea. We planned another attempt to reach the area during Hilary’s Christmas holidays in December, 1978. There is no settled weather season in Irian, but we hoped that this choice of date would give time for political problems to calm down. For seventeen months we traced and contacted people for first, second and third-hand reports of what was happening in Irian Jaya, and kept our eyes on the papers. Reports were conflicting. While the Indonesian government said its troops in West Irian were merely settling tribal disputes ‘over trifling matters like dowries, cattle and women,’ the Free Papua Movement was claiming the Indonesian Air Force had napalmed the jungle villages which gave the guerrillas their chief support. It did not help us that the Carstensz Pyramid was so near the Freeport copper mine at Ertsberg, a prime target for guerilla attack. We were told it had had its pipeline blown up in 1977 and a helicopter shot down.

By November, 1978, however, the trouble in the Carstensz region was thought to be largely over and we were encouragingly reassured that in Indonesia all things are possible, regardless of what officials say in the first place. So Hilary and I decided to go to Jakarta and try to sort things out from there. But as we arrived, at the first stage of our journey, Charlie and Ruth Clarke’s house in Islington (on the 6th December), we were no more certain that we would ever reach the Snow Mountains than we had been when the idea first germinated, two years before.

The Clarkes’ home has one of those rare generous atmospheres that allow you to walk in, struggle past the dog, cats, toys, children and put the kettle on to make a cup of tea. Ruth’s dramatic manner and Charlie’s air of detached nonchalance provide hours of entertainment – they could play themselves on television. When Charlie asked Ruth’s father for permission to marry her, he was told: ‘Good God, you must need a psychiatrist,’ which was fortunate because she is one – and he does.

Their house has become, over the last few years, a climbers’ London Base Camp. Climbers’ wives, girlfriends and widows find a comforting haven there, professional freelance climbers use it as their London office, and expeditions use it as their springboard – the last night before Heathrow, and on their return for the first bed and bath they’ve seen in weeks.

Chris Bonington and his road manager were there, in London on a lecture tour. I got out some photographs and unfolded the large Australian ‘Operational Navigation Chart 1:1000,000 1968’, on the kitchen table. I described our journey to them all.

‘From Jakarta we’ll fly to this island here, called Biak, and from there to Nabire on the coast of the mainland. Then, we’ll charter a light plane to Ilaga, just five days north of the mountains, and walk in. See these large white spaces, “Relief data incomplete.” It’s very difficult to map the place from the air, because it’s always so cloudy.’

‘Blank on the map, eh?’

‘Where are these gorillas?’

‘Ooh look, they wear those things on their dicks.’

‘I’m worried about you two, I hope you’ll be all right by yourselves.’

The telephone rang. It was Bernard Domenech from Marseilles. He and another French climber, Jean Fabre, were also going to try to reach the Snow Mountains. We had heard about each other’s plans during the summer, and had met in Chamonix. Now we exchanged last-minute details. We had agreed not to travel together, since a group of four would attract more attention and imperil our chances. However, we hoped to see each other in the hills.

‘We’re leaving next week. See you somewhere perhaps,’ he said.

Hilary and I spent our last day hunting through London shops for mosquito nets and silica gel bags to keep our cameras dry. Her hands moved quickly and intelligently as she squeezed vast piles of equipment into our rucksacks, after carefully hiding our ropes and climbing hardware at the bottom – we were to travel as tourists.

‘Just think – that biscuit you’re eating’ll come out in Indonesia,’ Ruth said.

‘Or over Bangkok,’ said Charlie.

On the 8th December we left Heathrow for Frankfurt – the first leg of our journey to Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia. Frankfurt was gripped by a fierce winter storm and we were delayed there for six hours whilst ice was cleared from the runway. Free drinks were provided and a boozing team developed, mostly comprising Welsh rugby players who started singing songs. When at last we settled back into the DC10, night had fallen and most of the rugby players fell asleep. Hilary and I sat on the port side. As we took off there was a loud bang and flash from the engine on the wing next to us. A few minutes later we heard the deep growl of the captain’s voice:

‘Ladies and gentlemen, the port engine has just blown up. We shall go up to 20,000 feet, eject all our fuel and return to Frankfurt.’

The careful delivery in a foreign accent gave the message an extra impact of uncertainty. There were a few nervous titters from the passengers.

‘How many more engines are there?’ I whispered.

‘Two I think.’

‘These things don’t glide do they?’

Irian Jaya.

We saw the fuel being ejected as the wing lights flashed. Then the long descent began. It was difficult to believe that this brightly-lit tube containing hundreds of people was not on the ground, but plunging earthwards through the night. I felt my pulse rate. It was soaring. I glanced at a few passengers to see if they were as nervous as I was. Two rugby players were fast asleep. Hilary and I put our boots on and stuffed our pockets with money, cameras and passports.

The plane bumped down, and as we landed fire engines and ambulances raced towards us from all directions and strung out behind in a line of moving, flashing lights.

‘He can’t just reverse two engines or it’ll spin round.’

At last, at the end of the runway, we stopped. Everyone started talking at once. The two rugby players behind us yawned and stretched.

‘Where are we?’ one of them asked.

‘Frankfurt.’

As we stepped out of the plane we heard the pilot confess to someone: ‘When the engine exploded, I did not know whether to try to stop or to keep on going and try to take off. We just got up.’

So ended the second of the twenty-six take-offs that were to carry us to Irian Jaya and back. It was an unnerving beginning. Two days later the port engine had been replaced and we took off from Frankfurt again, this time without incident.

This was Hilary’s first expedition. On the previous two expeditions I had been on, to Changabang and K2 in the Himalayas, my climbing partner had been Joe Tasker. We were of equal abilities, and a poker-faced, competitive edge to our relationship gave impetus to our efforts. I had relied on Joe’s organisational drive a lot. Now I was with Hilary, I felt more responsible about the whole thing. I worried about obtaining the Surat Jalan (travel permit) and all the travel ahead of us. It was awesome going into a big Asian city for the first time, knowing no one, with so much to do. Still, one obstacle had to be taken at a time. I opened Teach Yourself Indonesian, and tried to learn some words.

Jakarta seemed many cities rolled into one, with tall international skyscrapers pushing into a hot, drizzly sky and contrasting with the tight cluster of small houses – the kampongs – where most of the people lived. Waves of tiredness washed over us in the sultry heat as we tried to find the correct police office initialled M.A.B.A.K. When eventually we arrived it was closed for the day. It was the first encounter of an eleven-day trail through corridors of officialdom. We went to the Garuda Airline office.

‘Can we have a flight to Biak, the day after tomorrow?’

‘Let’s hope so,’ smiled the girl behind the desk. At five-foot-two, Hilary seemed tall beside the tiny Javanese girls.

The next morning we went back to M.A.B.A.K. It was the start of a busy day. Nobody seemed deliberately obstructive, but nobody wanted to take the responsibility of saying yes or no.

‘We are tourists and we want a Surat Jalan to visit Irian Jaya. We would like to go to Biak, Nabire and Ilaga, if possible?’ I said.

‘Ilaga, in the interior? You must apply to the police in Biak for permission to go there, I can give you a Surat Jalan to go to Biak and Jayapura only. Will you come back at 2.00 p.m.?’

At 2.00 p.m. the permits were ready and, elated, we went shopping. Jakarta supermarkets contained all the lightweight foods we needed – at expensive prices. Fortunately, the Indonesian rupiah had been devalued by thirty per cent a few weeks before. Everyone in the shops grinned helpfully.

Early the next morning the domestic airport of Jakarta’, Kemajoran, was in apparent turmoil and hundreds of people were waving and thrusting with tickets in their hands. Nobody spoke English. I tried to persuade Hilary to check in: ‘They won’t push a woman,’ I said. We strained to hear the words that would tell us our flight was about to leave.

‘Why did Sukarno change all the place names? We didn’t learn those in geography at school.’

‘Ujung Pandang, Amon, Biak.’

‘That must be us!’

At Ujung Pandang, which used to be called Makassar, we changed planes in the shimmering heat and were soon flying through towering clouds above coral islands. When we landed on the island of Biak that afternoon we saw our first Papuans, smiling in yellow uniforms as airport porters. They looked African, with their black skins, woolly hair and broad noses and feet, but apparently they are not closely related. They have no affinity in language, culture or race with the other peoples of the Pacific, the Malayans and Polynesians, and have only tenuous links with the Aborigines of Australia. Although the Papuans were not tall by European standards, they seemed huge to the tiny Indonesians, and Indonesian legends are full of conflicts between the good princes and the ‘giants’ who inhabited the jungles. The Papuans of Biak speak one of the hundreds of languages of New Guinea – the world’s most complex linguistic region.

We found a large, damp hotel near the airport. It used to be popular in Dutch days. Now, many Papuans wandered around it doing little jobs, as the whole mildewed edifice seemed to be crumbling around their ears. These were the lucky ones. There were many others still roaming the town who had also come from the mainland looking for work. We were the only guests in a large dining room. Outside we could see hot steamy coral and the blue sea. Small lizards ran around the walls. In one corner was a bar with no drink behind it, and in another stood a large Christmas tree with cotton wool and flashing lights. A cassette player was blaring out old Beatles’ numbers and traditional Western Christmas carols to Indonesian words.

There used to be a Biak legend that vast wealth would one day arrive from the East. After the Second World War, the Japanese departed and generous Americans, rich in material things, arrived. It seemed that the prophecy had been fulfilled. But now they, too, had gone.

In the morning we were interviewed by a policeman. In his immaculate uniform he looked firm and tough. I remembered what a climbing friend, John Barry, had said about Indonesians: ‘Bloody good scrappers’. He had fought against them as a Royal Marine in Borneo in 1964.

We presented a list of the villages north of the mountains: Bilorai, Beoga and Ilaga. ‘We want to fly to them from Nabire,’ we said. ‘We want to see the people who live there.’

‘I can only give you permission to go to Nabire. You must ask there about places further on’.

Our Surat Jalan was duly stamped, and the immigration office extended our visas.

‘Things are going too well,’ I said, ‘we haven’t had to bribe anyone yet.’

At an efficient little travel agency run by a Chinese – always the business men of South East Asia – we booked places on the scheduled flight next morning to Nabire. The travel agent warned us that we would not be able to charter a plane in Nabire because there was a fuel shortage in the whole of Irian Jaya. We decided, nevertheless, to take the chance.

There were only four other passengers in the Twin Otter. We veered around enormous clouds towards the mainland of Irian Jaya.

The tiny outrigger canoes of Biak shrank to specks on the ocean below us. We crossed the island of Yapen in a few minutes. Isolated tall trees reached out of the dense jungle and there were no signs of human habitation. The clouds became thicker. We could see the long fingernails of the pilot’s hands on the controls.

‘I hope he knows where the coast is,’ said Hilary.

Then we saw the long airstrip pointing out to sea, first built by the Japanese during their years of occupation. On the shore a white ship with a rust-stained hull was being unloaded across the surf by tiny figures in little boats. Behind the flat town of tin roofs rose a steaming jungle.

Once we had landed, would-be helpers buzzed around us. A small lively European with a goatee beard stepped through a milling throng, shook our hands and introduced himself as Father Tetteroo, a Franciscan missionary.

‘I am saying goodbye to a Sister who is leaving on the plane. Come round to my little house this evening for coffee. It is next to the airstrip. Everyone knows where I live.’

A friendly but insistent policeman perused our Surat Jalan, and this inspection attracted an even larger crowd of onlookers. We were whisked away to the only hotel in the growing town of fifteen thousand people.

The hotel manager spoke good English – his father was Dutch. He asked if he could help us. I told him we wanted mainly to go to Ilaga.

‘Why?’ he asked abruptly. His manner was grave and stern.

Momentarily, I dropped my guard, and forgot our strategy, confessing that we wanted to go to the Snow Mountains.

‘Impossible. Impossible,’ he repeated adamantly.

The whole area was closed. Only two weeks ago a missionary at Ilaga was ‘taken’. He did not even think it worth asking the police, but eventually agreed to introduce us to them. As we walked with him, he puffed at a pungent cloves cigarette and remarked that he used to be the Chief of Police. We had lost the chance of secrecy.

At the police post we discovered that the Chief of the Nabire Police was not there – he was in Biak. So we went round to the house of the second in command. I produced my Australian map – it was the best they had seen – and systematically asked about all the other approaches to the mountains. We all sat at a table and chickens scratched around our feet. It was difficult to follow the gist of the conversation, because they were laughing and smiling at the same time as stone-walling our plans. Had I been to the Himalayas? I showed them a little photo of myself on the top of Everest. But why did we want to go to the mountains of Irian? Was there gold there?

Anyway, it was impossible; we could not approach the mountains from the north. However, the southern approach via the Freeport Indonesia copper mine was in another police district – they offered to ask the Jayapura authorities to see if they would allow us to use that way of reaching the mountains.

I knew that even if the Jayapura authorities allowed us to go to the south, the people at the mine had already refused us entry in response to an earlier request. We had heard at Biak that when the guerillas blew up their pipeline, the mine had been put out of action for three months. It seemed most unlikely that tourists would be allowed now.

In the evening we went round to see Father Tetteroo, the man we had met at the airport. He was among the first group of missionaries to come to the interior, in 1937. He knew Colijn and Wissell, who had explored part of the Snow Mountains in 1936. In the early days, he and other priests had crossed the jungles of Irian on foot, often travelling for months at a time with a couple of porters. Very few of the tribes they met had seen Europeans before. He had not heard about Pearl Harbour until a month after the raid had occurred. He had been in a Japanese Prisoner of War camp for three and a half years – a camp which had been bombed mistakenly by the Allies. He delighted and fascinated us with his insights about Irian. His stories were simple, like parables, and directed outwards with a lively sense of fun – and mischief.

Father Tetteroo was sixty-seven years old.

‘Why should I go back to Holland, where I shall be retired? I prefer to stay here and help life wherever I can. I shall stay here until I die.’

He was full of joy, as if he would bounce back no matter how hard life knocked him. He lived simply. When we left him a present of a large bunch of bananas had appeared on the porch. He did not know who had left them there; it could have been anyone in Nabire. We walked back across the airstrip, feeling selfish in our pursuit of the mountains. We could absorb so little, compared with the lifetime experience of a missionary. In the distance, lightning flashed beneath anvil-shaped clouds.

‘Ah well, it was worth coming, just to meet him.’

‘Perhaps we should make the best of a bad job and try to get to those mountains in Borneo.’

‘We could go on a trek somewhere in Irian where there are no problems – then we would at least meet the people.’

But we were sad at heart.

All this way, all this money, to be refused on the doorstep of the fabled mountains. We decide to stay till Monday and give the police another try.

Next morning they seemed to relent. As long as the Jayapura authorities agreed, we could fly to Bilorai and walk out via the mine. No political troubles in the interior were mentioned, but we guessed that the main problems near the mountains were north-east of them, in the Ilaga Valley. Bilorai lay to the north west. Obviously, the Indonesians would not want to risk the international outcry if two Europeans were kidnapped as a symbolic protest by guerillas. The police promised to radio to Jayapura immediately.

Caught up in a mood of optimism, we went to see Tom Benoit, a pilot who serviced the Catholic missions in Irian. An American from Minnesota, he lived in Nabire with his wife Mary and two little daughters — with another on the way. He had flown over ten thousand hours in Irian.

Tom was short and stocky, relaxed and practical, and wearing a pair of long garish surfing shorts. ‘He likes to help people,’ Father Tetteroo had said of him. I asked him if he could squeeze us in on a flight to Bilorai. I was very aware of using people, capitalising on their open goodwill, and I apologised.

‘Somebody’s got to climb mountains,’ said Tom. He could fit us into his schedule on Monday morning. ‘I’m rather busy at the moment. One of our pilots – an Indonesian – disappeared a few months ago. He got lost in the clouds and flew into a mountain.’

‘We’re white parasites waiting for permission for our own ego trip,’ Hilary whispered to me after we had left.

Nabire slept during the hottest part of the hot day. When the shops reopened, we went provisioning to the blare of a loudspeaker van bellowing the name of the evening film at the cinema. The shops, mainly owned by Indonesian small traders from all over the archipelago, stocked a wide variety of Western goods, and we bought food for three weeks.

Over the centuries a trickle of Indonesians had settled on Irian’s coasts, leaving the interior’s forbidding jungles to the strange Papuan tribes they had found there. However, the shopkeepers of Nabire had arrived in the wake of a more recent influx of immigrants, resulting from the Indonesian government’s transmigration scheme. This scheme arose initially from President Sukarno’s opposition to birth control, and was aimed at relieving the population problems of farming in Java, and also at increasing the strength of Indonesia’s ethnic toehold in Irian. The government wished to make the moves as attractive as possible to the Javanese, and offered transportation, land, the corrugated iron for a roof, and sufficient food until the first harvest to those families who agreed to relocate. If the transmigrants become homesick, however, the return ticket is discouragingly expensive.

In the evening Tom showed three home movies he had taken in Irian. They whetted our appetites.

‘This is Bilorai a couple of years ago,’ he said.

‘Sure you don’t mean three thousand years ago?’

‘You won’t find them much changed now.’

Bad news arrived the following afternoon. The police had received an instruction from Jayapura that we would not be allowed into the interior until we had received authorisation from two organisations, LAKSUSDA in Jayapura and LIPI in Jakarta. To obtain this we would have to fly a circle – a thousand miles to Jakarta and then over a thousand miles back to Jayapura at the other end of Irian Jaya. Hilary and I started miserably snapping at each other. Now we had tasted Indonesian bureaucracy, we knew that, even if we could afford the travel, we could never obtain such documents. Next week the rules would probably be different. Our pile of recently-bought food and all our packed equipment in the corner looked pathetic – mute but lucid witnesses to the state of our fortunes. We would return to Biak the next day.

Dawn was the best time in Nabire, and we made the most of our last few hours there. Despite our setbacks, we felt affection towards the Indonesians as we watched the transmigration camp come to life. When the first rays of light sprayed skyward through the tall trees, the jungle chorus started as if at the signal of a baton. The noises faded just as suddenly when the sun appeared. There was a roar of engines as Tom took off on his first flight. We walked along the road to the settlement and were soon walking against the tide of hundreds of people, on scooters and on foot going to school, to work in the shops, government offices and at the airport, and perhaps just going for a walk like us. Everyone greeted each other and us gaily with shining eyes and contagious smiles. ‘Salamat pagi!’ Our faces became fixed grins. We walked to the Javanese market, past houses on stilts, fields of maize and bananas, a mosque, and a few cows, goats and dogs. Then we returned to the hotel for breakfast.

The manager came up with another straw of hope to clutch at: ‘At Biak you must go and see Mr Engels, who owns two hotels and a building company and exports wildlife to European zoos. He is a very powerful and influential man. He will help you to ask the Major General for permission to approach the mountains via the mine.’

At the airport building there was a confusion over the tickets. We pushed our way on to seats in the aeroplane. Our precious dollars were melting into flights and hotels as the days ticked by.

‘If we want to move away from problems, I think we’ll have to move away from Indonesia,’ said Hilary. The flight between Nabire and Biak had lost its excitement now.

At Biak we checked into one of Mr Engels’ hotels. It had a vast, extravagant painted Toroja roof, built of thousands of matched pieces of bamboo laid one upon another like tiles, sweeping up in a great curved prow at either end. A legend says that the design of the Toroja roof reflects a folk memory of the ships in which the distant ancestors arrived from China.

Mr Engels had a strong personality. He gave us a rapid resume of his life history and sent us to the Freeport office with his son, William, but all in vain. Even when I phoned the mine direct, the word was a firm but polite no.

‘Come back next year, I shall organise everything for you,’ promised Mr Engels.

Eventually we decided to do the one thing nobody had suggested, fly to Jayapura. At least then we would have tried everything.

We pressed our faces against the windows of the aircraft as it followed the coast, gazing longingly at the jungle, which harboured unknown wandering tribes of sago eaters. These people, we had read, hunted and collected food from the sago forests and occasional small- scale shifting cultivation. They had no contact with white people or administration, and spoke their own languages. Sometimes they traded in this jungle, leaving and collecting stone axes, salt and cowrie shells in traditional clearings, without ever seeing the tribesmen with whom they were exchanging goods. Through the jungle wound great meandering rivers which left a trail of oxbow lakes and emptied many channels into the sea.

Jayapura was once called Hollandia by its Dutch administrators – a name flashed around the Western world when General MacArthur spearheaded a battle against the Japanese there in 1944. Even now the rusting hulk of a partly-sunken Japanese transport ship projects out of the town’s beautiful blue bay. The change of place names reflects the tide of political fortunes. Hollandia has been re-named Kota Baru (new town), Sukanapura and, recently, Jayapura. Meanwhile, West New Guinea has been known as West Irian and Irian Barat and has only in 1973 become Irian Jaya (literally, Irian Victory).

Before landing, the plane circled over a landscape as gentle as a Chinese watercolour, open pale-green hills, red volcanised soil and large blue lakes whose shores and islands were clustered by houses built over the water on stilts. ‘At least it’s a change of scenery,’ I said. Hilary was busy taking photographs for her geography classes.

Jayapura’s airport is twenty-eight miles out of town, so before leaving I decided to investigate the possibility of flights to Bilorai, and left Hilary guarding our equipment. First I went to a large hangar run by a missionary alliance of the twelve different Protestant sects who operate in the highlands. Two tall Americans with crew-cuts ignored me, but eventually I found an office with two Indonesians inside it. The conversation lasted about a minute. There was no possibility of chartering a plane until the second week in January. Christmas was coming and they were too busy to have anything to do with us.

I decided to try the Catholics. A small boy pointed out a house where a Catholic pilot lived, but nobody answered the door. I walked back to Hilary, feeling as helpless as I have ever felt in my life and tiring of the indignity of asking people for favours. We found the large brown police building where our fate would be decided next day, and went away to type a letter to take with us describing what had happened so far. We looked for someone to translate it, and met Father Frans Verheijen, who agreed to come to the police building and help us. There was a pragmatic, straight-talking air about him, of someone used to getting things done – a quality he shared with the other Franciscan missionaries we had met. Next morning we followed him in, past guards and secretaries and along corridors until we were outside the room of the Chief Intelligence Officer of Irian Jaya.

‘Wait outside,’ said Father Verheijen. We sat down, trying to gauge the mood from the ebb and flow of conversation next door. Hilary had her fingers tightly crossed. Long minutes passed and eventually we were summoned in.

Politely, we were shown our seats. Humbly we looked across at two immaculately-uniformed Indonesians sitting beneath a large map of Irian Jaya. One of the men was holding an ominous-looking folder full of papers. Evidently it was the mountaineering file, because he recited the familiar words of the letter, written one and a half years before from Jakarta, cancelling our previous expedition plans. It was the last official – and thus definitive – statement on mountaineering expeditions ‘until I have better news from Irian Jaya.’ Red rings around many of the districts indicated trouble spots. The village of Bilorai was in an all-clear region, but the area south of the mountains was clearly ‘no go’. We were told that an agreement had been reached to allow us to visit Bilorai as tourists, but we were to promise not to go to the mountains. If we went near the mountains, we would be thrown out of Indonesia. The police considered all scientific, surveying and mountaineering expeditions to be forbidden. We were issued with new Surat Jalans, and asked to sign them after these conditions had been typed upon them. We agreed. Everyone smiled and we left.

We blinked in the sunshine outside and thanked Father Verheijen, who rushed off to attend a meeting. He had used all his powers of persuasion and influence, and lain his integrity on the line – and that of the missions he worked for – to help us, two complete strangers.

‘We’ll see the people at least,’ said Hilary ‘and perhaps we’ll be able to see the mountains from a distance. But if only they hadn’t found out we wanted to go to the mountains!’

‘Let’s just see what happens,’ I said. ‘Anyway, the next problem is to try and get a flight organised.’

Back at the airport we found a commercial charter company with one Australian pilot. Although he was away for the day, there seemed a possibility that he could fly us – until we calculated the price. We could not afford a thousand U.S. dollars. We trailed round to the Catholic pilot’s house. His flight schedule was stretching him to the point of tears. He told us that in Irian the Catholics had only two pilots with four planes, but they had enough work to keep six busy. However, he had a suggestion to make. The Seventh Day Adventists had a grass strip a few miles away, and maybe had more spare time to help. He didn’t know much more about them, except that they had split from the main Protestant missionary alliance owing to a disagreement about which day of rest to take at weekends – the Seventh Day Adventists refused to fly on a Saturday but, unlike the other sects in the alliance, they were willing to fly on a Sunday.

Eventually we found the strip, carved out of the jungle. Next to it were two modern houses and a hangar. The property was lavishly modern and well-cared for – evidence of the support of a wealthy religious commitment. We were nervous.

‘Watch out for the death-adders – stay away from the long grass.’ The wives of the sect’s two pilots were listening to their husbands conversing on the radio. ‘They’ll be back in a couple of hours,’ one said. ‘I’m sure they’ll try to help you.’

We went for a long walk along a narrow road through the jungle. We joked and flirted, trying to fill in time. Then, within minutes of each other, two tiny, snub-nosed Cessna 185s flew in noisily over the trees, arriving from opposite directions. We walked with slow steps to the hangar, bracing ourselves to bother people again. What would my response be, I thought, if a couple of strangers walked up to me in Leysin after I’d spent a hard day on the hill, and asked me to drive them to Geneva? I need not have worried.

‘It sounds like you need a bit of luck,’ said Ken.

‘I’ll fly you in tomorrow morning,’ said Leroy. ‘Be here at 5.00 a.m., I’m going to Jayapura right now – do you want a lift?’ The old American frontier spirit of help and co-operation had not died in the new age of competition. The tide seemed to be turning.

We had left most of our food in Biak – it was costing too much to pay the excess baggage every time we flew. Now we had twenty minutes before the shops closed to buy our rations. We found a large shop with a lot of Australian food displayed, and dashed from shelf to shelf until we had accumulated a large pile on the counter before an amused shop assistant.

‘I hope we haven’t forgotten anything.’

‘Look up Indonesian for ‘bulk-buy discount’, Hilary. You’ve got the dictionary.’

Leroy had not flown to Bilorai before, and before taking off we listened apprehensively in the half-light of the dawn as he discussed with Ken where it was:

‘Turn right at Ilaga … ’

I wondered if climbers discussing a route up a mountain sounded so casual. Then God was addressed very directly, in a strong clear prayer.

We flew along a compass bearing into the interior.

Already, the crisp morning air was being invaded by the first wisps of cloud floating up and starting to gather in bulbous shapes. After crossing some low mountains we approached the vast plateau of the Idenburg River. Below us stretched a dense jungle of sago swamps.

‘Where would you land in an emergency?’ I asked.

‘I’d look for a river,’ he said.

‘Where are the Snow Mountains?’

‘Over there somewhere – I’ve only seen them twice; usually they’re in the cloud. Mind you, I’ve only been flying in Irian for nine months.’