9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Vertebrate Digital

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

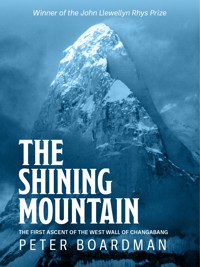

'It's a preposterous plan. Still, if you do get up it, I think it'll be the hardest thing that's been done in the Himalayas.' So spoke Chris Bonington when Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker presented him with their plan to tackle the unclimbed West Wall of Changabang - the Shining Mountain - in 1976. Bonington's was one of the more positive responses; most felt the climb impossibly hard, especially for a two-man, lightweight expedition. This was, after all, perhaps the most fearsome and technically challenging granite wall in the Garhwal Himalaya and an ascent - particularly one in a lightweight style - would be more significant than anything done on Everest at the time. The idea had been Joe Tasker's. He had photographed the sheer, shining, white granite sweep of Changabang's West Wall on a previous expedition and asked Pete to return with him the following year. Tasker contributes a second voice throughout Boardman's story, which starts with acclimatisation, sleeping in a Salford frozen food store, and progresses through three nights of hell, marooned in hammocks during a storm, to moments of exultation at the variety and intricacy of the superb, if punishingly difficult, climbing. It is a story of how climbing a mountain can become an all-consuming goal, of the tensions inevitable in forty days of isolation on a two-man expedition; as well as a record of the moment of joy upon reaching the summit ridge against all odds. First published in 1978, The Shining Mountain is Peter Boardman's first book. It is a very personal and honest story that is also amusing, lucidly descriptive, very exciting, and never anything but immensely readable. It was awarded the John Llewelyn Rhys Prize for literature in 1979, winning wide acclaim. His second book, Sacred Summits, was published shortly after his death in 1982. Peter Boardman and Joe Tasker died on Everest in 1982, whilst attempting a new and unclimbed line. Both men were superb mountaineers and talented writers. Their literary legacy lives on through the Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature, established by family and friends in 1983 and presented annually to the author or co-authors of an original work which has made an outstanding contribution to mountain literature. For more information about the Boardman Tasker Prize, visit: www.boardmantasker.com

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

the shining mountain

The first ascent of the West Wall of Changabang

The Shining Mountain

The first ascent of the West Wall of Changabang

Peter Boardman

www.v-publishing.co.uk

Contents

Foreword A Great Partnership

Chapter 1 From the West

Chapter 2 The Rim of the Sanctuary (22nd August-7th September)

Chapter 3 The First Stone (8th-20th September)

Chapter 4 The Barrier (21st-27th September)

Chapter 5 Survival (28th September-2nd October)

Chapter 6 Recovery (3rd-8th October)

Chapter 7 The Upper Tower (9th-13th October)

Chapter 8 Beyond the Line (14th-13th October)

Chapter 9 Descent to Tragedy (15th-19th October)

Chapter 10 The Outside (20th October-1st November)

Chronology

Foreword

A Great Partnership

Chris Bonington

It was 15 May 1982 at Advance Base on the north side of Everest. It’s a bleak place. The tents were pitched on a moraine the debris of an expedition in its end stage scattered over the rocks. Pete and Joe fussed around with final preparations, packing their rucksacks and putting in a few last minute luxuries. Then suddenly they were ready, crampons on, rope tied, set to go. I think we were all trying to underplay the moment.

‘See you in a few days.’

‘We’ll call you tonight at six.’

They set off, plodding up the ice slope beyond the camp through flurries of wind-driven snow. Two days later, in the fading light of a cold dusk, Adrian Gordon and I were watching their progress high on the North East Ridge through our telescope. Two tiny figures on the crest outlined against the golden sky of the late evening, moving painfully slowly, one at a time. Was it because of the difficulty or the extreme altitude, for they must have been at approximately, 27,000 feet (8230 metres)?

Gradually they disappeared from sight behind the jagged tooth of the Second Pinnacle. They never appeared again, although Peter’s body was discovered by members of a Russian/Japanese expedition in the spring of 1992, just beyond where we had last seen them. It was as if he had lain down in the snow, gone to sleep and never woken. We shall probably never know just what happened in those days around 17 May, but in that final push to complete the unclimbed section of the North East Ridge of Everest, we lost two very special friends and a unique climbing partnership whose breadth of talent went far beyond mountaineering. Their ability as writers is amply demonstrated in their books.

My initial encounter with Peter was in 1975 when I was recruiting for the expedition to the South West Face of Everest. I was impressed by his maturity at the age of 23, yet this was combined with a real sense of fun and a touch of ‘the little boy lost’ manner, which he could use with devastating effect to get his own way. In addition, he was both physically and intellectually talented. He was a very strong natural climber and behind that diffident, easy-going manner had a personal drive and unwavering sense of purpose. He also had a love of the mountains and the ability to express it in writing. He was the youngest member of the Everest team and went to the top with our Sherpa sirdar, Pertemba, making the second complete ascent of the previously unclimbed South West Face.

As National Officer of the BMC, he proved a diplomat and a good committee man. After Dougal Haston’s death in an avalanche in Switzerland, he took over Dougal’s International School of Mountaineering in Leysin. He went on to climb the sheer West Face of Changabang with Joe Tasker, which was the start of their climbing partnership. It was a remarkable achievement, in stark contrast to the huge expedition we had had on Everest. On Changabang there had just been Pete and Joe. They had planned to climb it alpine-style, bivouacking in hammocks on the face, but it had been too cold, too great a strain at altitude, and they had resorted to siege tactics. Yet even this demanded huge reserves of determination and endurance. The climb, in 1976, was probably technically the hardest that had been completed in the Himalaya at that time, and Pete describes their struggles in his first book, The Shining Mountain, which won the John Llewelyn Rhys Prize in 1979.

Pete packed a wealth of varied climbing next few years. In 1978 both he and Joe joined me on K2. We attempted the West Ridge but abandoned it comparatively low down after Nick Estcourt was killed in an avalanche. In early 1979 Pete reached the summit of the Carstensz Pyramid, in New Guinea, with his future wife, Hilary, just before going to Kangchenjunga (the world’s third highest mountain) with Joe, and Doug Scott and Georges Bettembourg That same autumn he led a small and comparatively another team on a very bold ascent of the South Summit of Gauri Sankar.

The following year he returned to K2 with Joe, Doug and Dick Renshaw. They first attempted the West Ridge, the route that we had tried in 1978, but abandoned this a couple of hundred metres higher than our previous high point. Doug Scott returned home but the other three made two very determined assaults on the Abruzzi Spur, getting to within 600 metres of the summit before being avalanched off on their first effort, and beaten by bad weather on a subsequent foray. Two years later Pete and Joe, with Alan Rouse, joined me on Kongur, at the time the third-highest unclimbed peak in the world. It proved a long drawn out, exacting expedition.

Joe Tasker was very different to Peter, both in appearance and personality. This perhaps contributed to the strength of their partnership. While Pete appeared to be easy going and relaxed, Joe was very much more intense, even abrasive. He came from a large Roman Catholic family on Teesside and went to a seminary at the age of 13 to train for the priesthood, but at the age of 18 he had begun to have serious doubts about his vocation and went to study sociology at Manchester University. Inevitably, his period at the seminary left its mark. Joe had a built-in reserve that was difficult to penetrate but, at the same time, he had an analytical, questioning mind. He rarely accepted an easy answer and kept going at a point until satisfied that it had been answered in full.

In their climbing relationship had a jokey yet competitive tension in which neither of them being wished to be the first to admit weakness or to suggest retreat. It was a trait that not only contributed to their drive but could also cause them to push themselves to the limit.

Joe had served an impressive alpine apprenticeship in the early ’seventies when, with Dick Renshaw, they worked through some of the hardest climbs in the Alps, both in summer and winter. These included the first British ascent (one of the very few ever ascents) of the formidable and very remote East Face of the Grandes Jorasses. In addition they made the first British winter ascent of the North Wall of the Eiger. With Renshaw he went on to climb, in alpine-style, the South Ridge of Dunagiri. It was a bold ascent by any standards, outstandingly so for a first Himalayan expedition. Dick was badly frostbitten and this led to Joe inviting Pete to join him on Changabang the start of their climbing partnership.

On our K2 expedition in 1978, I had barely had the chance to get to know Joe well, but I remember bring exasperated by his constant questioning of decisions, particularly while we were organising the expedition. At the time I felt he was a real barrack-room lawyer but, on reflection, realised that he probably found my approach equally exasperating. We climbed together throughout the 1981 Kongur expedition and I came to know him much better, to find that under that tough outer shell there was a very warm heart. Prior to that, in the winter of 1980-81, he went to Everest with a strong British expedition to attempt the West Ridge. He told the story in his first book, Everest the Cruel Way.

Our 1982 expedition to Everest’s North East Ridge was a huge challenge but our team was one of the happiest and most closely united of any trip I have been on. There were only six in the party and just four of us, Joe, Pete, Dick Renshaw and I, were planning to tackle the route. Charlie Clarke and Adrian Gordon were there in support going no further than Advance Base. However, there was a sense of shared values, affection and respect, that grew stronger through adversity, as we came to realise just how vast was the undertaking our small team was committed to.

It remained through those harsh anxious days of growing awareness of disaster, after Pete and Joe went out of sight behind the Second Pinnacle, to our final acceptance that there was no longer any hope.

Yet when Pete and Joe set out for that final push on 17 May I had every confidence that they would cross the Pinnacles and reach the upper part of the North Ridge of Everest, even if they were unable to continue to the top. Their deaths, quite apart from the deep feeling of bereavement at the loss of good friends, also gives that sense of frustration because they still had so much to offer in their development, both in mountaineering and creative terms.

Chris Bonington

Caldbeck, September 1994

Peter Boardman.

Joe Tasker.

Changabang from the south-west.

The route up the West Wall.

Chapter One

From the West

‘Sitting huddled beneath a down jacket, sheltering from the sun, my back against a rock, I drank some liquid for the first time in four days. I was going to live. The photographs I took were purely a conditioned reflex; I would want one picture of this view, just as a reminder of the ordeal I had endured. The glacier, spread about before me like a white desert, was peopled by my imagination and over it hung the massive West Wall of Changabang, a great cinema screen which would never have figures on it.’

Joe Tasker had survived Dunagiri and had returned to life to the west of the Shining Mountain.

Autumn days passed; meanwhile I was in the western world.

‘Have you seen this letter?’ asked Dennis Gray across the office of the British Mountaineering Council in Manchester, where we both worked. ‘What a fantastic effort,’ he added. I picked it up. It was from Dick Renshaw, who had just been on an expedition to the Garhwal Himalaya with Joe Tasker. The magnitude of their achievement jumped out from its few words:

Dear Dennis,

We climbed Dunagiri. It took us six days up the South East Ridge. When we reached the summit, we ran out of food and fuel to melt snow into water. The descent took five days and we suffered. I got frostbite in some fingers and shall be flying home soon from Delhi. Joe’s driving the van back.

Yours,Dick.P.S. Congratulations to Pete on climbing Everest.

I sat down, filled with envy. Dennis was already on the ’phone to the local press. ‘Incredible feat of endurance … Just the two of them … Tiny budget … 23,000-foot mountain … Far more significant than the recent South West Face of Everest climb.’ I had to strain to hear the words above the clattering typewriters and rhythmic pumping of the duplicating machine. Beyond the plate glass windows, the red brick of the office block, the unkempt, lumpy car park, and the Home for the Destitute, I could glimpse the blue of the sky.

I stared dumbly at the trays of letters in front of me – access problems, committee meetings, equipment enquiries. Amongst them were invitations to receptions and dinners and requests to give lectures about the Everest climb – all demands to accelerate the headlong pace of my life. Their number diluted the quality of my work. ‘Everest is a bloody bore,’ screamed a voice inside my head. The previous evening I had given a slide show about Everest. It was as if I was standing aside and listening to myself. As time distances you from a climb, it seems you are talking about someone else. All the usual questions had rolled out at the end: What does it feel like on top? What do you have to eat? How do you go to the toilet when you’re up there? Is it more difficult coming down? How long did it take you? Don’t you think you’ve done it all now you’ve been to the top of Everest? What marvellous courage you must have!

Courage. Endurance. Those words drifted across the office and mocked my bitter mood of discontent. Meaningless. Courage is doing only what you are scared of doing. The blatant drama of mountaineering blinds the judgement of these people who are so loud in praise. Life has many cruel subtleties that require far more courage to deal with than the obvious dangers of climbing. Endurance. But it takes more endurance to work in a city than it does to climb a high mountain. It takes more endurance to crush the hopes and ambitions that were in your childhood dreams and to submit to a daily routine of work that fits into a tiny cog in the wheel of western civilisation. ‘Really great mountaineers.’ But what are mountaineers? Professional heroes of the West? Escapist parasites who play at adventures? Obsessive dropouts who do something different? Malcontents and egomaniacs who have not the discipline to conform?

‘Will you answer this, Pete?’

‘Oh yes, sorry.’

Rita, one of the secretaries, was holding a ’phone out towards me. ‘Someone’s ropes snapped, and the manufacturer says it isn’t his fault.’

‘O.K. I’ll deal with it.’ In the city, as on the mountain, there has to be a breaking point.

I had nearly died on Everest that September. With Sherpa Pertemba, I had been the last person to see Mick Burke, who had disappeared in the storm that swept over us during our descent from the summit. We had lost him on the summit ridge and it had been my decision to descend without him. But I had returned to the world isolated by a decision and experience I could not share. My internal resources had grown. At first, during the desperate struggle of the descent, I had a surge of panic. We nearly lost our way twice, and were constantly swept by avalanches in the blizzard, but then I felt myself go hard inside, go strong. My muscles and my will tightened like iron. I was indestructible and utterly alone. The simplicity of that feeling did not last beyond our arrival at Camp 6 and the thirty-six hours of storm that followed. But I was to remember it in the months that followed.

Now back in Manchester, I was tired and depressed. My life had become dominated by one event. On Everest, the summit day had been presented to me by a large systematised expedition of over a hundred people. During the rest of the time on the mountain, I had been just part of the vertically integrated crowd control, waiting for the leader’s call to slot me into my next allocated position. And yet, when I returned to Britain, as far as the general public were concerned I was one of the four heroes of the expedition, the surviving summiteers. The applause rang hollow in my loneliness and the pressures of instant fame, although short-lived, made me ill. I yearned hopelessly for privacy so that I could digest the Everest experience. I longed for time to allow the thoughts which came to me in the early morning to take on form and meaning again.

I was now public property and, after eleven weeks away from the office, was left under no doubt that I had been allowed on my last expedition for a couple of years. I had sixteen committees to serve. Yet I felt in need of some new, great plan – some new project. I wanted to see how far I could push myself and find out what limits I could reach on a mountain. At the age of twenty-four there seemed so many mountain areas and adventures just within my grasp.

I was envious of Joe Tasker and Dick Renshaw’s climb, not only because of the difficulty and beauty of the ridge they had climbed on Dunagiri, but also because I knew that two-man expeditions, in comparison with the Everest expedition, have a greater degree of flexibility and adventurous uncertainty and they generate a greater feeling of indispensability and self-containment.

Winter came; Joe Tasker walked into the office. He lived not far down the road, out of the city. I had not seen him since the early summer, when he had occasionally called in whilst organising his expedition.

‘How’s Dick getting on then, Joe?’

‘He’s got three black finger-tips – I don’t know if he’ll lose them or not. He’ll be out of climbing action for quite a while. He flew home after three weeks in hospital at Delhi.’

‘Must have been an epic; how long have you been back?’

‘Only a few days – the van died in Kabul and I had to hump all the gear home on buses.’

A few weeks later it was Christmas time. I was at the end of days of travelling to meetings and lectures and was back amidst the telephones and typewriters, wilting under the headlong rush of urban life. Joe came in and sat down next to my desk.

Somehow, for Joe, the Shining Mountain had become more than just a backcloth to a hallucinatory ordeal.

‘What do you think about having a go at the West Face of Changabang next year?’

I wished he had not asked so loud. Someone might hear him. ‘Yes, that would be good. Yes, I’d like to go; trouble is, I’ve just been off work for a long time on Everest – I don’t think I’ll ever get the time off for another trip next year.’

Joe seemed surprised how readily I had shown my interest. I had agreed instinctively, flattered at his trust in me.

It was the Christmas party at the BMC and soon, upstairs in the pub, Joe was talking to Dennis. Then he came over.

‘Dennis is really keen. He says, ‘Leave it to me, lads’ – thinks you might be able to get the time off, if the Committee of Management agree.’

I didn’t think they would, but kept quiet. I wasn’t mentioning this to anyone. Joe’s plans were sweeping me along.

There were now two fresh elements in my life. Joe Tasker and Changabang. I had never climbed with Joe, but was well aware of his reputation. We had met for the first time in the Alps in 1971, on the North Spur of the Droites. I was climbing with a friend, Martin Wragg, a fellow student at Nottingham University. We had started off on the route in darkness and had been intrigued to see two lights flickering a few hundred feet up the route. We passed them as dawn crept down the mountain – they were two English climbers who had been bivouacking – Joe Tasker and Dick Renshaw. ‘Never heard of them,’ I thought and climbed quickly on.

Martin and I were both too sure of ourselves, having climbed the North Face of the Matterhorn the week before. The Droites was badly out of condition, but we were young and inexperienced and kept on climbing as fast as we could. There was hard water ice everywhere, and I was forced to spend exhausting hours step cutting. But still these two climbers kept on close behind us. We couldn’t shake clear of them. By late afternoon we had traversed onto the North Face, trying to find easier and less icy ground. It was snowing and I was exhausted. If the other two had not been behind us, or had turned back, we would have retreated many hours before. There were no ledges and Martin and I sat on each other’s lap alternately through the night, while Joe and Dick bivouacked a little more comfortably a few hundred feet below. The following morning a storm broke and we teamed together to make twenty-two abseils back to the Argentière Glacier amidst streams of water, thunder and lightning. Once we reached the glacier, we split up.

I didn’t see Joe for another four years.

During those four years Joe did a lot of climbing in the Alps, mainly with Dick, and steadily, in a matter-of-fact manner with complete disregard for the reputation of routes, achieved a staggering list of ascents, culminating in the East Face of the Grandes Jorasses in 1974 and the North Face of the Eiger in the winter of 1975.

After Christmas I went to North Wales to the hut of my local climbing club, the Mynydd, and confided to a friend about the Changabang plans – a blundering, stupid thing to do, for my girlfriend overheard me, and it was the first time she had heard the news. Before, it had been Everest that had obsessed me. By an almost mechanical transfer it was now Changabang.

I was living at home with my parents in early 1975. I asked Joe and Dick round to my parents’ home for a meal. My mother, a keen reader of mountaineering magazines, laid on the full dining-room treatment. It was the first time my parents had met Joe or Dick. It was as if they were appraising Joe, examining the person who was taking their son away. Dick’s fingers were still being treated and looked alarming. The unspoken question in the air was ‘Joe’s come out of the ordeal on Dunagiri without any scars – will he do this to Pete?’ Throughout the meal, Dick was his usual quiet, polite self. Joe, however, was making digs and gibes about the size of the Everest expedition and the publicity it had received.

‘I don’t think the Everest climb was impressive as a climbing feat, but as an organisational one,’ he said.

I wondered if Joe must have resented the fact that I had been on Everest and not him. His achievement on Dunagiri had been formidable and far more futuristic in terms of the development of Alpine-style climbing in the Himalayas but, despite Dennis Gray’s efforts, had received nothing like the recognition of the Everest climb. It was a naive thought – I was being over-sensitive about Everest, and the sources of Joe’s ambitions were a closed book to me. However it was obvious that rather than feeling satisfied with his Dunagiri climb, it was as if he still had an itch that needed to be satisfied.

After the meal Joe showed me the slides he had taken of the West Wall of Changabang, which he had taken from the summit of Dunagiri and from the Rhamani Glacier just above their base camp, as he had found melted water after the Dunagiri climb. Joe and Dick had been so exhausted and unbalanced by their descent that they had split up and descended the last 1,000 feet down different sides of the ridge. Joe had staggered beneath the wall alone. He had been beyond thoughts of climbing then. Vague plans only began to formulate in his head during the long journey home. Examining the slides carefully, I was impressed and daunted. The face looked very steep and there were no continuous lines of weakness on it, only occasional patches of snow and ice between great blank areas of granite slabs and overhangs. This was Changabang.

Joe was not of the older mountaineering generation – on Everest I had felt in awe of the media images of climbers like Bonington, Scott and Haston – but here was someone with whom I could discuss the problems on equal terms.

‘Where’s this line then?’ I asked.

Joe was taken aback. ‘Well, it just looks like an interesting Face – I mean it can’t all be vertical – there’s snow and ice on parts of it. Anyway, when you get close to a seemingly blank wall, there are usually some features on it.’ He mentioned ice slopes and pointed to shadowy lines which could indicate grooves and cracks. Our fingers hovered on the screen. Joe felt it was a crucial moment:

‘Until I had a second opinion, I was not yet sure whether to regard it as a fanciful daydream or a feasible proposition. If Pete was sceptical about the feasibility of the project, the impetus would be lost and my belief in the venture would begin to wane. I wanted to draw from him some appraisal of the idea, but he was non-committal. I only realised slowly that his question arose not from doubt, but from interest – he was intrigued by the idea.’

I knew I must go there. I began to wonder if I would come back from such a wild enterprise – to succeed seemed impossible.

‘What do you think, Dick?’ I asked.

‘It looks as if it might go,’ said Dick. But then he did not have to try and prove it. My mind took a great leap and accepted the whole project.

This climb would be all that I wanted. Something that would be totally committing, that would bring my self-respect into line with the public recognition I had received for Everest. My experience on Everest had left an emotional gap that needed to be filled. The BMC had agreed that I could take another two weeks’ holiday on top of my four-week allowance to go and attempt it. I longed for the summer to arrive, and saw the long, intervening months as time to be endured.

Meanwhile, Joe was doing most of the work for the expedition. The first problem was to obtain permission from the Indian Government to make an attempt. Some Lakeland climbers were planning a route for the South Face and already had permission. Joe set about trying to persuade them and the Indians to allow us to go. Neither was happy at first. Joe, however, had powerful friends in India and, despite an early discouraging letter from the Indian Mountaineering Foundation that said, ‘We do feel that a team of two climbers attempting a peak like Changabang will be unsafe’, friendly persuasion was applied and the permission eventually arrived not long before we left. The Mount Everest Foundation gave us a modest grant, after several members of the committee had expressed the sentiment ‘that a team of four might be more advisable’. All this was fuel to Joe, encouragement to his awkwardness when faced with obstructions. An iconoclast by nature, he had no respect for the cults and legends that surround personalities and preconceptions in the mountaineering world.

I met Ted Rogers, one of the Lakeland team, whilst out climbing on Stanage Edge in Derbyshire one weekend. I asked him if they minded us going to the other side of the mountain. After all, they had been planning their expedition for nearly two years. Our organisation, in contrast, was at the last minute. His reply was rather guarded.

‘Joe usually seems to get his way,’ he said.

Chris Bonington was the patron of their expedition and he had told Ted that he considered Joe’s and my plans as ‘preposterous’. ‘Still,’ he added to us at a later date, ‘if you do get up, it’ll be the hardest route in the Himalayas.’

On occasion through the spring, Joe and I met to discuss our plans for the expedition. Joe had acquired a temporary job working nights in a frozen food distribution centre in Salford. Every night he was in a huge cold store for several hours, where the temperature was between minus fifteen and minus twenty degrees Celsius. Much to the amazement of his workmates, who were always well wrapped up, he worked without his gloves on for most of the time, loading small electric trucks from the corridors of racking laden with frozen vegetables, meat, fish, ice-cream, cream cakes, chocolate éclairs – everything to cater for today’s pre-packed way of life. It was not an enthralling occupation, but it meant that he was at home in the daytime and could attend to the work needed to organise the expedition during the day. He dashed about in a dilapidated car, stereo blaring wildly, his thoughts full of Changabang and his talk full of lurid stories about the complicated love lives of his fellow shift workers.

During snatched moments of spare time, I read books about the exploration of the area of the Garhwal, in which Changabang stands. I started by reading The Ascent of Nanda Devi by Bill Tilman, about the successful expedition to the highest mountain in India in 1936. I had the strange feeling that I had read it before. Then I realised that the book I had read before was Eric Shipton’s Nanda Devi, in which he described the adventures that he and Tilman had met the year before, when they first penetrated the high ring of peaks that guard Nanda Devi and reached the Sanctuary at its foot.

They were the first human beings to reach there, and the story had a Shangri La quality to it, touching far back into the promised land of my subconscious. I had read the book when I was thirteen. Tilman’s book jerked my memory and I re-read the book, in particular the passages where Shipton makes his first steps into the inner Sanctuary of the Nanda Devi Basin:

At each step I experienced that subtle thrill which anyone of imagination must feel when treading hitherto unexplored country. Each corner held some thrilling secret to be revealed for the trouble of looking. My most blissful dream as a child was to be in some such valley, free to wander where I liked, and discover for myself some hitherto unrevealed glory of Nature. Now, the reality was no less wonderful than that half-forgotten dream.

The words bumped around inside my head like a bell which had only just stopped ringing. Here was a subtle relationship between real place and mental landscape. I was becoming a willing victim of the spell of the Garhwal.

The mountaineer of today cannot hope to capture that feeling. Today’s frontiers are not of promised lands, of uncrossed passes and mysterious valleys beyond. Numbers of ascents of many mountains in the Himalayas are now into their teens. Today, the exploring mountaineer must look at the unclimbed faces and ridges and bring the equipment, techniques and attitudes developed over the past forty years, rather than the long axe and the plane table. There are so many ways, so much documentation, that only the mountaineer’s inner self remains the uncharted.

Changabang had been climbed for the first time in 1974, by a joint British-Indian Expedition led by Chris Bonington. Like all wise first ascensionists of Himalayan peaks, they chose the easiest, most accessible line – the South East Ridge. In June, Joe and I heard the news that a six-man Japanese expedition had climbed the South West Ridge. They had used traditional siege tactics – six climbers had used 8,000 feet of fixed rope, three hundred pitons, one hundred and twenty expansion bolts in the thirty-three days it had taken them to climb the South West Ridge. This news was, for us, surprisingly encouraging. We were beginning to think – from the comments of other British climbers – that Changabang was unclimbable by any other route except the original. Chris Bonington had announced our plans to the mountaineering public at the National Mountaineering Conference, and this had provoked a lot of comment.

‘You’ll never get up that wall, you know,’ said Nick Estcourt.

‘I don’t think so either,’ said Dave Pearce, ‘but I think it’s great that two of you are going to have a go.’

‘It doesn’t look like a married man’s route,’ said Ken Wilson, editor of Mountain Magazine.

We consulted all the British members of the first Changabang climb.

‘You’ll have your time cut out,’ said Dougal Haston.

Joe asked Doug Scott for his opinion of the chances of climbing the Face, looking for some sort of reassurance.

‘Beyond the bounds of possibility, youth.’

‘Well, you’ve got to go and have a look.’

‘Yes, youth, you’re right. I’d take an extra jumper with you though,’ then – two days later – ’phoned Joe up to ask if he might come. We were bent on a two-man attempt and to have more would increase opinions and divide the purpose of the unit. Just two of us would make the dangers and decisions deliciously uncomplicated.

On one, well-oiled night in the Padarn Lake Hotel in Llanberis, Brian Hall staggered across: ‘I think it’s great that just two people have got permission for a route like that – it shows that the Indian Mountaineering Foundation are at last beginning to move with the times. But if something happens to you it will mess things up for people who want to go on small expeditions in the future.’

Meanwhile, Joe Tasker was asking Joe Brown about the difficult rock climbing he had just done at 20,000 feet on Trango Tower in the Karakoram. When he told Joe about our plans, the veteran Brown wrinkled his oriental eyes with a calm born of experience and said, ‘Just the two of you? Sounds like cruelty to me.’ The consensus of opinion was that we stood no chance at all of succeeding; only close friends thought that we would do more than make a noble effort before retreating.

Don Whillans, however, was encouraging. He himself had planned to go to Changabang in 1968, with a team including Ian Clough and Geoff Birtles, and Don lent Joe and me a number of pictures of the West Face he had acquired from various sources. He looked at one of them and, planting a stubby finger on the icefield in the middle said, ‘Well, you’ll be able to climb that all right – you’ll just have to get to the bottom of it, and then from the top of it up that rock wall above it.’ He ended by summarising the situation neatly: