Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

In 1943, and with Allied victory in North Africa imminent, 1st Special Air Service Regiment was in danger of being disbanded. However, with the timely and vital intervention of Major Robert Blair Mayne, the unit was saved and replaced by an organisation known as HQ Raiding Forces, and Mayne was appointed to command the Special Raiding Squadron. The heroic spirit of 1st SAS Regiment continued to thrive in the squadron, and Paddy Mayne – as he was known to his soldiers – was an inspiration to those he commanded. Through action in Sicily in July 1943, undertaking distraction missions in Bagnara and finally aiding the Eighth Army in Termoli before being recalled to the UK to aid the SAS with the invasion of France, Paddy's Men worked as a well-oiled, dangerous and fiercely loyal unit, performing skilfully under the immense pressure of war. In this book Stewart McClean provides an illustrated history of the Special Raiding Squadron, detailing the formation of the unit, the lives of the men and their operations during the Sicilian and Italian campaigns, and the extraordinary man who commanded the squadron: Robert Blair Mayne DSO, or Colonel Paddy Mayne as he became famously known throughout the world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 277

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

About the Author

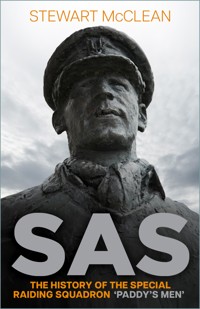

Stewart McClean served in 102 (Ulster) AD Regiment (V) as Battery Quartermaster BQMS. This unit was the successor to a number of Northern Ireland-based Gunner regiments, including 8th (Belfast) HAA Regiment into which Robert Blair Mayne was first commissioned in 1939. Mayne was appointed to 5 Light AA Battery which was raised in Newtownards, the author’s home town. These facts have contributed to Stewart McClean’s long-time interest in the wartime career of Blair Mayne, known as ‘Paddy’ to all who served with him. In 1997 a memorial was dedicated in Newtownards and the author was a member of the group that campaigned for this tribute to a local hero. As he explains in his introduction, this was also the occasion that sparked his interest in the Special Raiding Squadron, an SAS unit whose members were proud to call themselves ‘Paddy’s Men’. He currently lives in Northern Ireland.

Front cover illustration: Statue of Lt Colonel Blair (Paddy) Mayne, SAS, standing in Conway Square, Newtownards. (Martin Conroy/Alamy Stock Photo)

First published 2006 by Spellmount

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Stewart McClean, 2006, 2024

Maps © The History Press, 2006, 2024

The right of Stewart McClean to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 697 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Special Air Force: Song of the Regiment

List of Maps

Chapter I Changing Times

Chapter II A New Role

Chapter III Final Preparations

Chapter IV Another Step Closer

Chapter V Into Action

Chapter VI Completion

Chapter VII Augusta: Daylight Operation

Chapter VIII Bagnara: A Foothold on the Italian Mainland

Chapter IX Termoli: The Hardest Battle

Chapter X Triumph and Tragedy

Chapter XI Counter-attack

Appendix I The War Record of a Glorious Monarch

Appendix II The Men and Leadership of the Squadron

Appendix III Nominal Roll

Appendix IV Recommendation for the Victoria Cross

Dedication

A statue was unveiled and dedicated on 2 May 1997 to the memory of Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Blair Mayne DSO*** in the town square of his hometown, Newtownards. The Earl Jellicoe KBE DSO MC unveiled the bronze statue before handing over to the Very Reverend Fraser McLuskey MC MA BD who performed the dedication. These two men were accompanied to the ceremony by a contingent of former members of the Special Air Service Regiment. I had the great privilege and honour of meeting one of those men, Mr Terry Moore MM, the following morning and the first thing that struck me about him was his absolute modesty. During our conversation, he informed me that it was the wish of many of the men that The Special Raiding Squadron should be given its rightful place in history and so, over the next two years, Terry was responsible for providing me with the means of gathering much of the information contained in these chapters. He personally ensured that countless doors were opened for me, many of which I could only ever have dreamed about. Terry also introduced me to many of his friends and former comrades who had served so gallantly with him during those dangerous and difficult times. On another occasion he made it possible for me to attend an annual reunion held in Hastings where he introduced me to all assembled as the person who would tell the true story, a very hard cross to bear.

I would also like to say thanks to the men, and their wives, who gave freely of their time, patience and considerable knowledge: David Danger, Alex Muirhead, George Bass, Sid Payne, Bob Francis, Bob McDougall, Arthur Thomson, Duncan Ridler, Reg Seekings, Derrick Harrison, Nick Thurston, Jack Nixon and Douglas Monteith. It became a labour of love and Terry was always just on the other end of the telephone. ‘Moore here, how can I help?’ was his cheerful greeting. Sadly he is no longer with us but I agree totally with a statement made to me by the late Alex Muirhead during one of our many conversations: ‘I firmly believe that he is up there watching you.’

God bless, Terry and thank you.

Stewart McCleanNewtownardsSeptember 2005

Acknowledgements

While my name will be seen as the author of this book there are some people who really must be acknowledged for their support and assistance. These include Paul Rea, who first introduced me to the pleasures of a day’s research and a good meal; Derek Harkness for his continued support (at times he was behind me, beside and in front of me as required); and Richard Doherty who allowed me the use of his literary expertise and his considerable military knowledge. Mrs Christina McDougall is a formidable lady and I am grateful for her friendship and advice.

A special word of appreciation goes to my wife Carole, who has, perhaps, had to contend with more than most and is wholly responsible for this book being finished.

And, finally, my two children, Alan and Holly.

Stewart McCleanNewtownardsCo. DownSeptember 2005

List of Maps

1. Principal area of Allied Operations 1943

2. Eighth Army Operations in Sicily after D-Day for Operation HUSKY

3. Italian operations, showing Bagnara

4. Eighth Army operations in Calabria

5. The Battle of Termoli

Chapter I

Changing Times

The Special Raiding Squadron was formed in the weeks leading up to the end of the campaign in North Africa, which came to a close on 12 May 1943, and comprised men and officers drawn from 1st Special Air Service Regiment. The formation of this particular unit could have been regarded as a compromise since many senior officers at General Headquarters in Cairo felt that 1st SAS had outlived its usefulness as a fighting force and should be disbanded. The men would then either be sent back to their own regiments, or posted to the remaining Commando units or the Royal Marines where all their exceptional skills and qualities could be put to much better use. There was also a very considerable element within the GHQ staff that disliked the thought of this small irregular unit, over whom they had little or no control, fighting their own separate wars. They saw its members as undisciplined mavericks rather than the effective fighting force into which they had developed. Rules that did not relate to their type of warfare were simply bent or broken with new and more appropriate ones replacing them. Perhaps the real reason behind the GHQ attitude was a perceived threat to authority from some of the new ideas and methods that had begun to appear on, and off, the battlefields.

Nearing the end of 1942 the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who was known to be an avid supporter of the commando and special forces’ ethic, had asked the commanding officer of the Special Air Service, Lieutenant-Colonel David Stirling, to provide him with his thoughts and ideas regarding the future development of tactics. It is highly possible that some people, on reading Stirling’s communication, may have heard alarm bells starting to ring very loudly. The contents of the letter, which was classified as secret, envisaged the officers who commanded the SAS taking overall charge of all forthcoming special operations; the soldiers who formed the other units involved would then either be absorbed into their ranks or, at least, be controlled by them.

MOST SECRET.

PRIME MINISTER

1. I venture to submit the following proposals in connection with the re-organization of Special Service in the Middle East. (“Special Service” may be defined as any military action ranging between, but not including, the work of the single agent on the one hand, and on the other the full scale combined operation.)

(1) That the scope of “L” Detachment should be extended so as to cover the functions of all existing Special Service units in the Middle East, as well as any other Special Service tasks which may require carrying out.

(2) Arising out of this, that all other Special Service units be disbanded and selected personnel absorbed, as required, by “L” Detachment.

(3) Control to rest with the officer commanding “L” Detachment and not with any outside body superimposed for purposes of co-ordination, the need for which will not arise if effect be given to the present proposals.

(4) “L” Detachment to remain hitherto at the disposal of the D.M.O. for allocation to Eighth, Ninth and Tenth armies for specific tasks [Ninth Army served in Palestine and Tenth in Iraq]. The planning of operations to be carried out by “L” Detachment to remain as hitherto the prerogative of “L” Detachment.

2. I suggest that the proposed scheme would have the following advantages:

(1) Unified control would eliminate any danger of overlapping, of which there has already been more than one unfortunate instance.

(2) The allocation to “L” Detachment of all the roles undertaken by Special Service units would greatly increase the scope of the unit’s training, and thereby augment its value to all ranks, who will inevitably greatly gain in versatility and resourcefulness.

(3) The planning of operations by those who are to carry them out obviates the delay and misunderstanding apt to be caused by intermediary stages and makes for speed of execution which in any operation of this kind is an incalculable asset. It also has obvious advantages from the point of view of security.

SignedDavid Stirling9.8.42

But fate meant that Stirling’s far-reaching and innovative plans would never be implemented. In late-January 1943 he was betrayed by a group of Arabs and captured by Germans while endeavouring to meet up with First Army in Tunisia. The detractors of the new form of warfare may then have concluded that with Stirling in enemy hands, and no longer able to use his considerable influence, or his wide circle of friends and contacts in high places to pull strings, they had been handed an ideal opportunity to make some radical changes. Thankfully for all those who had fought so hard throughout the desert campaign this was not allowed to happen. Had it done so, it surely would have ranked alongside some of the biggest military blunders of the Second World War.

The small band of élite, highly trained, highly motivated and mobile soldiers who had originally formed the SAS had been responsible for destroying considerable numbers of aircraft, vehicles and equipment as well as causing damage to roads, railways and communications. They had also destroyed some of the Axis’ much-needed petrol and oil supplies, although the greatest damage to such supplies had been caused by the Royal Navy and Royal Air Force, which, using Ultra decrypts, had been able to destroy tankers en route to North Africa from Italy and Greece. The SAS’s wide-ranging and highly successful activities had caused frequent disruption in the rear areas of the Axis forces in Libya and ensured that troops assigned to guard duties on vital installations remained on their mettle. On one raid, Blair Mayne, Stirling’s second-in-command, is believed to have destroyed more enemy aircraft on the ground than any single RAF fighter ace of the war; the figure of over 100 enemy aircraft destroyed by Mayne exceeds the highest-scoring RAF ace by some thirty machines. However, the story that Mayne ripped control panels out of German aircraft with his bare hands is highly unlikely, especially when one considers the quality of German workmanship. One former SAS soldier did recall that Mayne pulled the control panel out of a Regia Aeronautica Fiat CR42 biplane while the soldier was underneath the aircraft looking for the fuel tank.

Principal area of Allied Operations 1943

However, the exploits and heroic deeds of this small band of men were, and remain, the stuff of legend. Nothing, however outrageous it may have seemed to others, was beyond them as they roamed freely and fought the bewildered Axis forces at will. With their comrades of the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) they became masters of hit-and-run tactics and, added to the destruction on the ground, and the tying up of German and Italian troops on guard duties, they also forced the Axis to deploy many men to scour the vast expanses of open and barren desert for their elusive attackers. Fear was also a major weapon in the SAS armoury; on many occasions even the thought of an attack on their positions caused widespread panic within the enemy ranks. News of the SAS success had reached the highest levels of the command structure in Nazi Berlin and, added to the many commando raids on mainland Europe, led Adolf Hitler to issue his infamous Kommandobefehl on 18 October 1942.

The Führer

SECRET

No. 003830/42g.Kdos.OWK/Wst

F.H. Qu

18.10.1942

12 copies

Copy No.12.

1. For a long time now our opponents have been employing in their conduct of the war, methods which contravene the International Convention of Geneva. The members of the so-called Commandos behave in a particularly brutal and underhand manner; and it has been established that those units recruit criminals not only from their own country but even former convicts set free in enemy territories. From captured orders it emerges that they are instructed not only to tie up prisoners, but also to kill out-of-hand unarmed captives who they think might prove an encumbrance to them, or hinder them in successfully carrying out their aims. Orders have indeed been found in which the killing of prisoners has positively been demanded of them.

2. In this connection it has already been notified in an Appendix to Army Orders of 7.10.1942 that, in future, Germany will adopt the same methods against these Sabotage units of the British and their Allies; i.e. that, whenever they appear, they shall be ruthlessly destroyed by the German troops.

3. I order, therefore:-

From now on all men operating against German troops in so-called Commando raids in Europe or in Africa are to be annihilated to the last man. This is to be carried out whether they be soldiers in uniform, or saboteurs, with or without arms; and whether fighting or seeking to escape; and it is equally immaterial whether they come into action from Ships and Aircraft, or whether they land by parachute. Even if these individuals on discovery make obvious their intention of giving themselves up as prisoners, no pardon is on any account to be given. On this matter a report is to be made on each case to Headquarters for the information of Higher Command.

4. Should individual members of these Commandos, such as agents, saboteurs etc., fall into the hands of the Armed Forces through any means – as, for example, through the Police in one of the Occupied Territories – they are to be instantly handed over to the S.D.

To hold them in military custody – for example in P.O.W. Camps, etc., – even if only as a temporary measure, is strictly forbidden.

5. This order does not apply to the treatment of those enemy soldiers who are taken prisoner or give themselves up in open battle, in the course of normal operations, large scale attacks; or in major assault landings or airborne operations. Neither does it apply to those who fall into our hands after a sea fight, nor to those enemy soldiers who, after air battle, seek to save their lives by parachute.

6. I will hold all Commanders and Officers responsible under Military Law for any omission to carry out this order, whether by failure in their duty to instruct their units accordingly, or if they themselves act contrary to it.

(Signed) A Hitler

As a direct result of that order many from the regiment, the commandos and other special forces would suffer inhumane treatment and torture in France at the hands of the SS and Gestapo before being brutally murdered.

It took a week of very hard bargaining and talking throughout a series of meetings in Cairo by Major Mayne, where he used his negotiating skills to great effect, to gain his objective. Over the years it has been wrongly, and sometimes wilfully, implied that he stuttered and stammered through those meetings or was incoherent when speaking in front of senior ranks. The real truth of the matter was that he was a very softly spoken man who, nevertheless, could present his case very eloquently. Yet should the need arise force could be used when he felt that it was required or that it best suited his purpose. Although he had gained a first class university education, although he had not completed his studies when war broke out, came from a good social background and was well travelled, he was neither a member of the upper class nor the landed gentry and in some quarters the old boys’ network still prevailed. Or possibly it was due to the fact that he did not, and would not, conform to many of the outdated views on how war should be fought that he was never regarded as a particular favourite. Mayne was also trying to come to terms with the death of his father, William, on 10 January 1943 and with the refusal by his superiors to allow him compassionate leave to attend the funeral. Almost certainly that would have weighed very heavily on his mind because his family played a hugely important part in his life.

However, he eventually managed to convince GHQ of how wrong the decision to disband the regiment would be. He had achieved his primary goal of keeping his men together as a fighting force and had also been given command of the newly-formed Special Raiding Squadron. It has been documented that David Stirling had managed to make contact with GHQ from captivity and recommend Mayne to succeed him as commander but there could never have been any other choice; Mayne’s personal record of mayhem and destruction caused to German and Italian forces spoke volumes. Added to his large catalogue of feats was the fact that while still only a lieutenant (temporary captain) he had been awarded the Distinguished Service Order for his bravery and leadership during raids on the desert airfields of Sirte and Tamit. The citation reads:

At Sirte on 12/13 December 1941 this officer was instrumental in leading and succeeded in destroying, with a small party of men, many aeroplanes, a bomb dump and a petrol dump. He led this raid in person and himself destroyed and killed many of the enemy. The task set was of the most hazardous nature, and it was due to this Officer’s courage and leadership that success was achieved. I cannot speak too highly of this Officer’s skill and devotion to duty.

For a junior rank to be awarded the DSO is regarded as second only to the Victoria Cross.

It can, therefore, be asserted that without the timely intervention of Major Blair Mayne the Special Air Service would have been disbanded. As a prime mover during their hard won battles, it was only fitting that Mayne should be the man to lead them into the future.

Chapter II

A New Role

And so, during the early months of 1943, the next chapter in the history of the regiment was about to begin. Although they still had great respect for Stirling’s original ideas and his considerable achievements, especially in the formation of the regiment, many, if not all, the soldiers and officers felt that it was only when Mayne took command that the pace really picked up. He established himself quickly as an outstanding and inspirational leader while his men trusted his judgement without question and were dedicated totally to him, which is almost certainly why they referred to themselves as ‘Paddy’s Men’. The young soldiers who had been among the first to volunteer for L Detachment were all intelligent, skilled individuals who had been hand-picked after rigorous and highly dangerous selection procedures and training exercises. That they would follow him anywhere without fear or question speaks volumes about just how Mayne was regarded by them. His men were also very aware that, while he fully accepted and understood that some lives would inevitably be lost during subsequent fighting, he would never allow them to be sacrificed or used as cannon fodder.

Mayne was responsible for instilling many fine qualities in his men but he constantly stressed one point to make sure that they were always very aware of it: ‘Every man has to be his own saviour and has to be totally self sufficient.’ To many that might have seemed a small and very simple statement but it contained an enormous meaning and would become the ethos for every man in the regiment, then and now. He was always thinking about the wellbeing of his soldiers as was illustrated during a rest break while driving through the desert on a mission. Terry Moore was resting beside a jeep when Mayne suddenly asked him: ‘Now tell me, Moore, we’ve all just been wiped out and you’re the only survivor – how would you get back to where we’ve just come from? ’Without stopping to think, Moore answered: ‘Well, I’d just follow the wheel tracks in the sand.’ ‘But there are no tracks left because the wind would have blown them all away.’ Mayne lowered his voice and looked straight at the young soldier: ‘You’ve got to think all the time.’

But, like it or not, changes were inevitable and as with every compromise there was a price to be paid. That price was to be a reduction in overall strength to somewhere in the region of 300/350 men of all ranks as well as a change of role: under the new title of Special Raiding Squadron they would become assault troops. In the eyes of many they would be more akin to shock troops. Without doubt Paddy Mayne would control how his men fought and performed in their upcoming battles but he knew that he had lost the right to choose their future battlefields.

Prior to David Stirling’s untimely capture and Mayne’s eventful meetings in Cairo, A Squadron 1st SAS had been transferred for further training to the Middle East Ski School at The Cedars in Lebanon. That move had been made as a precaution due to the strategic threat posed by the German advance in the Caucasus. Had there been a German southward move from that region British forces, including Mayne’s Squadron, would have had to fight in the mountainous regions of Turkey, Iraq or Persia. Training complete, however, the Squadron returned to its desert base in Kabrit where, with the rest of the regiment, the soldiers were to be told of their future. The newly promoted Major Mayne awaited them and, as always, he was a man of swift action. Eager to get started before any other changes might be implemented, he briefed them all immediately on the outcome of his short stay in Cairo. He also informed them that he would select the officers and senior non-commissioned ranks whom he wanted to accompany him; he would leave it to the discretion of those officers and NCOs to choose their own men. As the assembled ranks dispersed they knew that, at least for the foreseeable future, those chosen would remain together. The following figure shows the command structure.

Squadron HQ Officers

Squadron Commander

Major R B Mayne DSO

Second-in-Command

Major R V Lea (struck off strength, Palestine, 8 Aug ‘43)

Admin Officer

Captain E L W Francis

Medical Officer

Captain P M Gunn

Intelligence Officer

Captain R M B Melot

Padre

Captain R G Lunt (detached to SS Bde, 31 July ’43)

Signals Officer

Lieutenant J H Harding (RFHQ, Palestine, 20 July ’43)

Mortar Detachment Commander

Lieutenant A D Muirhead (A/Captain from 16 May ’43)

No.1 Troop Officers

Troop Commander

Major W Fraser

Section Commander

Lieutenant J Wiseman (A/Capt from 6 Oct ’43)

Section Commander

Lieutenant A M Wilson (A/Capt from 16 May ’43)

Section Commander

Lieutenant C G G Riley

No.2 Troop Officers

Troop Commander

Captain H Poat (A/Major and Sqn 2 i/c from 8 Aug ’43)

Section Commander

Captain T Marsh

Section Commander

Lieutenant P T Davies

Section Commander

Lieutenant D I Harrison (A/Captain from 8 Aug ’43)

No.3 Troop Officers

Troop Commander

Captain D G Barnby (Apptd Adjutant 8 Aug ’43)

Section Commander

Captain E Lepine (Apptd Tp Comd vice Barnby 8 Aug ’43)

Section Commander

Lieutenant M H Gurmin (Struck off strength, Palestine, 8 Aug ’43)

Section Commander

Lieutenant J E Tonkin

Their new role meant that there would be a large influx of new soldiers who would have to be integrated quickly into the various sections and apprised of the regiment’s methods. These men would be drawn from all parts of the Army and their skills as signallers, drivers, engineers and medics were much needed. But not all the new arrivals would be totally unfamiliar. Sid Payne was a member of the Special Boat Squadron but felt that he was due for a change.

I simply packed my kitbag and waited in Cairo for Paddy and his squadron to return. I approached him and simply asked if it would be alright for me to join his men. He told me that he could think of no reason why not and said that it should be fine. He also told me not to worry as he would see to all the necessary paperwork. So I just jumped onto the back of a lorry and that was that.

But, despite all the upheavals, things moved along at a considerable pace and within a week a small advance party under the command of one of the recently arrived officers, Lieutenant Derrick Harrison, had been despatched to set up a new camp and make things ready for the arrival of the rest of the troops.

The main body of the newly established Squadron travelled up from Egypt by train and, almost immediately after their arrival, began a period of heavy and intensive training at their new base at Az Zib, a small, remote village in northern Palestine close to the Syrian border. Although there were some small buildings that could be used for storing essentials, the accommodation for the majority of the troops would be tents. It proved to be an almost ideal location since the hilly terrain and rocky areas surrounding the base provided excellent training areas. The soldiers laboured for many long hours learning how to handle and use the large scaling ladders, ropes and equipment needed for climbing cliff faces but, knowing only too well from experience that those items would not always be available to them, they went even further and practised climbing the rock faces using only their bare hands. As if the rigours of climbing were not difficult and arduous enough the decision was taken that this had also to be accomplished while carrying the full weight of personal equipment and weapons. When they felt that the conditions they were working under made it necessary, they also refined and rewrote the training manuals. On other occasions they devised new methods that they felt suited better their own personal needs; exceptional men required exceptional training. Nothing was left to chance and so all those highly demanding and dangerous exercises had to be carried out during both daylight hours and darkness. The construction and laying of explosive charges would be a new skill for some as would be the use of the many different types of fuses or time pencils needed for demolition work. The explosives training was placed under the control of a small section of Royal Engineers who had been attached to the Squadron.

However, a number of men who had seen action in the desert would have been old hands with improvised explosive devices as they had trained and fought alongside Jock Lewes who had invented a completely new type of sticky bomb for the destruction of enemy aircraft. As well as having the incendiary properties required for the job, its lightweight construction meant that more could be carried on raids. Lewes’s invention became legendary and was rightly named after him, the Lewes Bomb. Another major priority for all concerned was learning how to handle and operate the various types of German and Italian weapons that they might encounter. Weapons were, after all, the tools of their chosen trade and quite a few preferred to use the German MP38/MP40 machine pistols when the chance arose. That particular weapon had an extremely good rate of fire and as the ammunition fired by it was substantially lighter they could carry larger quantities. While the Mk 4 Lee–Enfield was a thoroughly good rifle, and the mainstay of the British Army, its bolt action could be slow, even in the best of hands. It was also fairly heavy and cumbersome which was a disadvantage for close-quarter fighting. The Thompson submachine gun, more commonly known as the Tommy gun, was another preferred weapon and with either the 30-round box or 100-round drum magazine was good for tight situations, such as house clearance, where automatic fire often made the difference between life and death.

The Squadron’s men knew that they would be travelling mainly on foot and so would be without their ubiquitous Willys jeeps. Those tough little vehicles had allowed them to carry their heavier weapons into many battles but their mainstay in the future for them would have to be the .303 calibre Bren gun. During their desert raids they would have carried somewhere in the region of a thousand rounds and twenty to thirty magazines with them aboard their jeeps. Those figures would have been greatly supplemented by what they had stashed away in various hiding places. But for physical and practical reasons they would have to make do with greatly reduced numbers of approximately 300 rounds and ten magazines per weapon. Each individual magazine had a capacity of only thirty rounds, although it was normal practice to load only twenty-eight rounds, but the gunners could put this firepower to devastating use. (The practice of loading the magazine with twenty-eight rounds was intended to extend the life of the springs that held the bullets firm in the magazine. When circumstances demanded, the full load could be used.) Each magazine was usually loaded with a mixture of the three types of rounds available: ball, tracer or armour piercing.

Compared to some of the machine guns used by the enemy the Bren had a relatively slow rate of fire at 500 rounds per minute but that was far outweighed by its superb accuracy and outstanding reliability. However, Paddy Mayne, who was regarded by all as an excellent shot, was forever berating and shouting at the gunners for firing in long bursts. He much preferred them to use controlled bursts or what was commonly known as double tapping, two shots in quick succession. Private Jack Nixon, a veteran of No.7 Commando before he joined the SAS, was one of those unlucky men who came under constant verbal attack for keeping his finger on the trigger longer than necessary. Because of the barracking he had to suffer, Jack was often heard muttering under his breath as he jokingly referred to Mayne: ‘That man is the bane of my life.’ Nixon’s skill with the Bren was well known and his prowess would be heavily tested throughout the coming months. Private Douglas Monteith, another former commando who had served with No.8, was glad to note on many occasions that ‘Jack was incredible with that thing and I was just glad that he was on our side and not shooting at us’.

Countless hours were spent training and carrying out practice drills until it all became second nature. Every aspect of daily routine, however trivial it might have appeared, was carried out at the express orders and under the watchful eye of Paddy Mayne who, to an outsider, might have appeared to be a ruthless tyrant who was utterly relentless as he constantly drove his men onwards. On many occasions they would be pushed extremely close to their personal limits but, as was common practice with him, Mayne took part in whatever happened and was the main driving force behind everything. At times it must have appeared to many of the new men that they were being treated like a bunch of raw recruits all over again. Even the most basic of subjects and skills had to be covered from scratch. Shooting and fieldcraft carried a great importance but it was absolutely vital that everyone knew how to map read using the stars and find a compass bearing. But, to their credit, the men never faltered or complained in the slightest because they understood only too well why all of that familiarisation and retraining was necessary.