Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

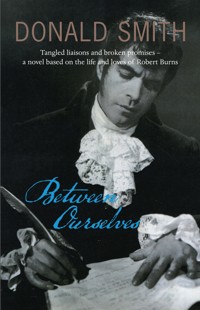

The six months that Robert Burns spent in Edinburgh, between the Aryshire years and the short-lived maturity in Dumfries, were an intense time in the life of a poet who became a Scottish hero. Burns is an icon, but he is a flawed one. The great bard was fond of drink, women and over familiar with Edinburgh's underworld. He was often conflicted with crippling self-doubt about his talents and bitter about his place in society. Duringhis short time in Edinburgh, Burns had dealings with the infamous Deacon Brodie; was struck by inspiration and failed by his muse; and, fell in love with two unavailable women and bedded many more than that. While never straying from accepted Burns' history, this remarkable novel imagines the life of Burns' in those months to discover the flesh and blood man behind the legend. BACK COVER Among the dirt and smoke of 18th century Edinburgh, the great poet ponders his next move. Frustrated with the Edinburgh literati and the tight purse of his publisher, Burns finds distraction in the capital's dark underbelly. Midnight assignations with working girls and bawdy rhymes for his tavern friends are interupted when he is unexpectedly called to a mysterious meeting with a dangerous man. But then Burns falls in love, perhaps the only real love in a lifetime of casual romances, with beautiful Nancy, the inspiration for 'Ae Fond Kiss'. Donald Smith has woven the real life love affair of Nancy and Burns into a tantalising tale of passion and betrayal, binding historical fact and fiction together to create an intimate portrait of Burns the man.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 243

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DONALD SMITH was born in Glasgow to an Irish mother. Brought up in Glasgow and Stirling, he began work in Edinburgh as a theatre stage manager, becoming Director of the Netherbow Arts Centre in 1983. Donald has written, directed or produced over fifty plays, and is a founding Director of the National Theatre of Scotland.

Influenced by Hamish Henderson, Donald was also the moving spirit behind the new Scottish Storytelling Centre of which he is the first Director. One of Scotland’s leading storytellers, he has produced a series of books on Scottish narrative, includingStorytelling Scotland: A Nation in Narrative, Celtic Travellers,and a poetry collection,A Long Stride Shortens the Road: Poems of Scotland.The English Spy, his first novel, is set in the closes, courts and wynds of Edinburgh, the first UNESCO City of Literature.

Donald Smith’s study of Robert Burns and religionGod, the Poet and the Devil, is also published this year, the 250th anniversary of the birth of Burns.

Between Ourselves

DONALD SMITH

First published 2009

eBook edition 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-906307-92-9

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-04-5

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The publisher acknowledges subsidy from the Scottish Arts Council towards the publication of this book.

© Donald Smith 2009

Table of Contents

Author Bio

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Quotes

Author’s Preface

Edinburgh - December 1829

Edinburgh - October 1787 to New Year 1788 - The Journal

Edinburgh - January 1788 - A History of Myself

Edinburgh - January 1788 - An Account of the Life of Nancy MacLehose

Edinburgh - January to March 1788 - The Journal

Edinburgh - Fourth Day of November 1788 - Deposition of the Last Wishes of Jenny Clow, Formerly a Serving Maid

To Edinburgh, in darkness and in light

What an antithetical mind! – tenderness, roughness – delicacy, coarseness – sentiment, sensuality – soaring and grovelling – dirt and deity – all mixed up in that one compound of inspired clay!

George Gordon, Lord Byron, on reading some ‘unpublished and never to be published’ letters of Robert Burns

I paint the way some people write their autobiography. The paintings, finished or not, are the pages of my journal and, as such, they are valid. The future will choose the pages it prefers. It’s not up to me to make the choice.

Pablo Picasso, quoted by Françoise Gilat

One song of Burns is worth more to you than all I could think of for a whole year in his native country. His misery is a dead weight on the nimbleness of one’s pen… he talked with Bitches… he drank with Blackguards, he was miserable. We can see horribly clear in the works of such a Man his whole life, as if we were God’s spies.

John Keats

Author’s Preface

WE KNOW A lot about Robert Burns. But who was he behind the masks, the depressions and the verbal fireworks?

A lot of people, including several who feature as characters in this novel, burned their correspondence from the poet, even demanding back their own letters after his death. The closer you were the more likely you were to destroy the evidence. We know that Agnes McLehose – the much misrepresented ‘Clarinda’ – doctored her intimate communications with ‘Sylvander’. Burns’ brother Gilbert was very tight-lipped when the first official biographer Dr Currie came calling. Already the mythology of Scotland’s national poet was taking hold – a flawed icon but an icon nonetheless.

I have taken one intense period of Burns’ life – six months in Edinburgh – as the focus of my story. Day by day, these months became the defining pivot between the Ayrshire years and the short-lived maturity in Dumfries. There is nothing here that contradicts the researchers, yet for a novelist there are significant and creative gaps. What was the balance of the relationships with Peggy Chalmers and Jean Armour, with Clarinda and Jenny Clow? Were there others? And who did Burns fraternise with in the city’s lowlife haunts apart from his bosom cronies William Smellie and Bob Ainslie?

The women are at the heart of Burns’ Edinburgh crisis. Why has Agnes McLehose been variously labelled flirt and prude, Calvinist and cocktease? What lay behind Jenny’s stubborn refusal to give up her son to his father, even on her deathbed? I cannot pretend to fully recover these lost voices, but I have tried to listen to their accents and draw out their underlying experiences.

The reader also becomes party to these private communications. How do we tell the story of our own lives – selectively, confidingly, misleadingly? There are letters or emails, social masks and conventions. I am not making any judgements, least of all about Robert Burns, but I would like you to be on the inside of these relationships. In the end we all have to decide for ourselves.

EDINBURGH

December 1829

SARAH WAS STRAINING at the door to catch even a fragment of the conversation inside. But the voices were murmuring confidentially. The mistress received plenty of respectable callers, but a visit from Jean Armour, the widow of Robert Burns, was out of the ordinary, especially given the circumstances…

The sturdy old lady had arrived out of breath after walking all the way from the Glasgow coach stop in the Grassmarket. It was more than an hour since Sarah had taken in the tea, and been dismissed without pouring. Jean Armour was still a handsome figure, if a little stout.

In the cosy parlour discussion was drawing to a close.

‘He wis guid-hearted in his ain nature, hoosoever he driftit times intae foolishness.’

‘I believe that also. Robert’s virtues will outshine his faults as long as he has true friends to defend him.’

‘Aye an folk play fair.’

‘Precisely.’

‘Sae we’re agreed. There’s things aboot Rab naebody else need ken.’

‘Apart from us.’ Nancy’s eyes moved from the brown paper package between them to the wine glasses on the dresser which had been Burns’ last gift.

‘It’s been my wish since I turned up the box twa months syne. I culdna read it aa ower again. He wis bye wi it.’

‘But you felt I had to be consulted.’

‘That was it. Forbye we had never met. Is that no strange?’

Nancy leaned forward to put her dainty wrinkled hands on the countrywoman’s knees, and looked into her eyes.

‘You know, Jean, how much this still means to me.’

‘Aye, I think ah dae. He’s no easy forgotten.’

Nancy reached down and pushed forward the package. Jean stood up heavily and lifted it onto the hearth. Stooping down she opened up the wrapping to reveal a scuffed journal bound in black leather and three bundles of manuscripts tied with faded ribbons.

For a moment they looked at the worn relics. Every inch seemed covered with writing. Bending again, Jean handed one bundle to Nancy and took one herself, and with a last glance at each other they sent the two bundles into the coals. Quickly flames began to lick round the edges, then the top pages curled, blazed and blackened. As the fire sprang to work Nancy threw on the last bundle and they watched it burn. Finally Jean had the journal in her strong hands. She opened it wide and tore out a handful of pages. In it went, than another and another until the end boards themselves lay on top of the bier.

Ten minutes later when Sarah finally opened the door unsummoned to collect the tea things, the two old ladies were sound asleep beside a dying fire. A brown paper wrapper was loose on the rug and a thick wadge of paper with singed edges lay on top of the smouldering coals.

EDINBURGH

October 1787 to New Year 1788

THE JOURNAL

LAST STAY IN Edinburgh but not for long; hardly worth the notice.

But this sheaf of paper begun so many months ago is an accumulation of empty sheets, a harvest of nothings. I intended the observation of men and manners, reflection and self-knowledge, fields of science and some sheltered glades of poetry. Now the days and weeks stare back at me like featureless faces.

What is it about this place that gnaws the guts and nips my head? Why at ease with Scotland and out of sorts in Edinburgh?

Even arriving with acclaim already in my pocket, I spent the first week on a straw pallet with a sour belly. A sore mind turned in on itself. Now I am here marking time. How to arrive in Edinburgh?

Notwithstanding, my lodgings have moved upwards. Then I shared a bed with Richmond, barely raised above the stinking High Street causeway. Carts carting, criers crying, pisspots pouring and floozies fleering. The landlady demanded an extra eightpence since her mattress was burdened by two bodies in turn. What if it had been simultaneous?

Today I lord it in Newton, Edinburgh. My attic lair soars above St James Square, where the Old Town odours of gardez-loo are chased swiftly through gracious squares and out to sea by a stiff breeze. A sturdy timber bed, trig dresser with glass and two sash windows, one townward and one looking clear across to Fife. Auld Reikie is still in Scotland. This room might offer fresh perspective, given time and leisure.

Little Jean, the lassie of the house, comes tripping up to ask if I will take tea, and if I will hear her at the pianoforte. Both, of course, my lady, for neither can be refused. Nor should be. I must write a song for that sweet high voice. A song requites nature’s promise to her bard.

To bed with a miserable cold. Head oozing, throat rasping, and that old familiar tightening. Will these tearing stounds of pain gripe me again? A hellish deathman swinging at my vitals with a rusty scythe. One drooking at the plough or an ill-considered journey can lay the honest farmer on his back, at the mercy of his tormentors.

My weakness brings Betty from the kitchen hearth with a mustard poultice, steaming infusions and soothing toddies. An old countrywoman normally cooped below decks, she ascends with bulging eyes and wagging chins like an officious turkey. Loosing my shirt and breeches, she kneads at chest and belly, strong fingers teasing out swellings and inflammation.

I surrender myself to firm handling. Easeful relief, then pleasure. As my mind empties I inhale these pungent odours and let the muscles breathe out. For a moment I am a babe again in Betty Davidson’s sunburnt hands. Or a corpse to be anointed before wrapping in a shroud.

When I revived, Betty of St James Square had departed with all her cloths and steaming bowls.

Wrote a letter to Miller promising to come and see his farm as soon as I am better. Is this the offer which cannot be refused?

Much easier. But if I lie low Betty may climb again to minister to the poet, his body sliding back beneath snaw white linen. Birth, death and all the inbetweens rolled into one seamless consummation. Not today.

Comfortably on the pot for the first time in Edinburgh.

My desire for Peggy Chalmers is unlike anything I have felt before. With a mind as bright as her frame, Peggy is fresh and finely moulded. I want Peggy Chalmers who is my equal in every way. But she is denied me as if prison bars were fixed between us from head to foot. Without these she would rush into my arms. Our eyes spoke everything her tongue denied. And then she looked away.

It cannot be, her body cried. Why not? Why should the blind tyranny of social laws prevail? Are we not born to natural freedom? Or to harsh necessity. So I am banished back to books and rhymes, mocked by my first resolution on coming to the capital.

‘I am determined to make these pages my confidante.’ As well I might since no-one else attends my inmost feelings. Intimacy declined, the poet should consult his own entrails.

‘I will sketch every character who catches my notice with unshrinking justice.’ Some I can still bring to the bar; they know who they are. ‘Likewise my own story, my amours, my rambles.’

Well, circulating libraries may be supplied – the smiles and frowns of fortune on my bardship. Scotia mother of my dreams, should we be shamed by what we are at birth?

‘My poesy and fragments that never see the light of day will be inserted.’ Last year’s resolution. I could renew that pact, given sufficient leisure. Or is it boredom. Four shillings for the book with black endboards. So little can hardly have purchased so much friendship since confidences went to market. Honesty for sale! I’m in Edinburgh now, God help me. A glass of wine with soup may do no harm.

This is the drawing up of accounts. Then I can settle this business for once and all. I pull my chair up to the little table by the window.

The clouds are chasing each other over Calton Hill.

A package has arrived for me. A book, they say, passing it up by floors. A book for Mr Burns; its for the poet. The package sits in the centre of my table.

Pride of place, sirs, for The Scots Musical Museum, Volume One. Good old Jamie Johnson. A poor craftsman he may be but between these covers is the authentic spirit of Scotland. And two of my songs – ‘Green Grow the Rashes’ and ‘Young Peggy Blooms my Bonniest Lass’. Not the last Peggy, I swear. And I found him a rounded version of ‘Bonnie Dundee’, both verses. Though I still twinge when patching lines and stanzas to mend the shattered wrecks of these venerable compositions.

Johnson, sir, I salute you. A glass please for Caledonia’s true bard and only Muse – the People! Is there no brimming glass to hand? Aye, sneer if you care, drawing rooms of Edinburgh. A curse on your whinstane hearts, you Edinburgh gentry. But wait, who is that preening in the shadows? The Edinburgh Edition of Robert Burns. Stand aside and listen to Nature’s Muse.

Young Peggy blooms our bonniest lass

Her blush is like the morning

The rosy dawn, the Spring grass,

With early gems adorning.

Pity I cannae sing, but needs must in the absence.

‘It all began, your Ladyship, with old fragments found among our Peasantry in the west. Poor forgotten things, I had no idea anybody cared for them. I who had once known so many had forgotten them.’

Yes, indeed, heaven-taught ploughman.

‘The Poetic Genius of my country found me as the prophetic bard Elijah did Elisha, at the plough – and threw her inspiring mantle over me. She bade me sing the loves, the joys, the rural scenes and pleasures of my natal soil in my native tongue. I tuned my wild artless notes as she instructed. And more—’

There is more?

‘She whispered to me, come to the ancient metropolis of Caledonia, and lay your songs under my honoured protection. Now I obey her dictates and present to you, The Edinburgh Edition.’

And then she farted.

This is no time for petty reckonings. I must go and toast Johnson. Let Creech and his Edition wait tomorrow. Unhand me, Betty. The poet is whole again in all his parts.

Word is out; the poet is back. One brief sojourn at Dowie’s and Mr Burns’ public begins to clamour for further appearances. Prepare to repel boarders. The lumbering apeman Smellie and sleek man-about-town Bob Ainslie will have at us.

We form a trinity of sword, pen and pintle.

As for my printer, the reckoning is nigh.

Monies owed by William Creech bookseller to Robert Burns, Poet, for the Edinburgh Edition of hisWorks:

500 subscription copies £125

Balance Owing for Distribution to Subscribers £400

Property of Poems £100

Damn the bookseller’s discount. Restate as—

Subscription copies £125.00

Subscribers’ copies

(less discount at one quarter) £300.00

Property of Poems £105.00

______

£530.00

A tidy addition all of which Mr Creech has under his capacious belt, tightly fastened. More Leech than Creech. First call today.

Must also draft and deliver notes for Johnson. Volume One demands its successor like a lusty child brothers and sisters. Let us deliver the new arrivals to Scotland’s glory.

Interleaved notes in draft for James Johnson

One. Set lines to tunes nearer than printed.

Two. To ‘Here Awa, There Awa’ must be added this, the best verse in the song:

Gin ye meet my love, kiss her an clap her,

An gin ye meet my love, dinna think shame:

Gin ye meet my love, kiss her an clap her,

An show her the way to haud awa hame.

There’s room on the printer’s plate.

Three. For the tune of the Scotch queen, take the two first and the two last stanzas of ‘The Lament’ in Burns’ Poems.

Four. ‘To Daunton Me’ – the chorus is set to the first part of the tune, which just suits it when played or sung over once. So to set:

The blude red rose at Yule may blaw,

The summer lilies bloom in snaw,

The frost may freeze the deepest sea

But an auld man shall never daunton me

To daunton me, to daunton me

An old man shall never daunton me.

And auld Creech shall never daunton me. Let the piper be paid for his tunes. But for Jamie the lark, the throstle and the doo shall sound their woodnotes wild without restraint or hindrance.

Blue devils.

Ainslie put off for tonight. He may call in.

Interleaved page of letter to James Hay, Librarian and Composer to the Duke of Gordon

Allow me, Sir, to strengthen the small claim I have to acquaintance by the following request.

An Engraver, James Johnson in Edinburgh has, not from mercenary views but from an honest Scotch enthusiasm, set about collecting all our native songs and setting them to music; particularly those that have never been set before. Clarke, the well known musician, presides over the musical arrangement; and Drs Beattie and Blacklock, Mr Tytler of Woodhouslee, and your humble servant to the utmost of his power, assist in collecting the old poetry, or sometimes to make a stanza or a fine air when it has no words.

My request is ‘Cauld Kail in Aberdeen’, intended for this number, and I beg a copy of His Grace of Gordon’s words to it, which you were so kind as to repeat to me. You may be sure we won’t prefix the Author’s name, except you like. Though I look on it as no small merit that the names of many of the Authors of our old Scotch Songs will be inserted in this work. Johnson’s terms are for each Number, a handsome pocket volume, to consist of at least a hundred songs, with basses for the Harpsichord etc; the price to subscribers five, and to non subs six shillings. I rather write at you, but if you will be so obliging as on receipt of this to write me a few lines.

Damn all prevarications, but most of all their supreme commander, William Creech.

Harmoniously pissing and shitting as never before in Auld Reikie. On all other fronts ceasefire prevails.

She has a serious face beneath those tightly formed ringlets. The hair sits close round a finely moulded head. But she holds her head forward, shyly almost, above the slender neck. Hazel eyes, soulful; a strong nose (too strong?); the firm rosebud of a mouth; distant chin; breasts clear and pointed despite her diffident stance.

She listens intensely, submissive on the surface, then when she moves or speaks everything is alive, alight in motion. The eyes dance with flecks of understanding, a gleam of mischief.

My Peggy’s face, my Peggy’s form

The frost of hermit age might warm.

My Peggy’s worth, my Peggy’s mind

Might charm the first of humankind.

I love my Peggy’s angel air

Her face so truly heavenly fair

Her native grace so void of art

But I adore my Peggy’s heart.

Climbing ahead of me on the slope to Castle Campbell. She weaves nimbly through the trees, small but sure, perfectly poised. She turns to laugh at me clambering behind, her head haloed through sunlit leaves. What could I not be with such a soulmate, a polestar, a guide, a dancing delight? She brings out the best in me. I don’t boast to Peggy but share only my honest satisfactions. Like Mr Skinner’s poem in my praise – she knows its worth. I tell her the sensible things she wants to hear. On Thursday I will go to inspect Mr Miller’s farm – like the honest tiller of the soil she has in mind. My own Minerva. But she will not have me.

I used every resource of elegance – flourishes of hand, heart melting meditations, modulations of winning speech. All vain. My rhetoric’s usual effect is lost on her at least. She puts my sincerity to quiet scorn.

When did that arise? Why?

Peggy Chalmers stood apart; she held out against me. When she stayed on her father’s farm in Mauchline, I used to visit. Hers was a family lowered from high estate, yet connected to the best society. I passed smoothly from formal bows – the awestruck swain – to a careless arm around the waist. She brought me up hard and short, laying out in no uncertain terms the distance I had still to travel.

Yet I kept my head, cool and deliberate under fire. I asked her to forgive poor Rab o Mossgiel, whose only fault, whatever rank he had in life, was in loving her too much for his own peace. I had no formal design, outwith the nakedness of my own heart in this matter-of-fact tale. Of course she might wish to cut me off, imposing in effect a complete cure for lovestruck rustics. Or she might allow me to renew the beaten path of friendship.

That brought her back into line and when we met again in Edinburgh my devotions were a morning walk, heartfelt conversation, books and poetry, now and then a glance or pressure of the hand. Rarely, in some sequestered spot, I chance a gentle touch of lip on cheek, lip on lip.

Might Caledonia’s Bard not now aspire to Peggy’s lifelong companionship, crowning Miss Chalmers’ sweet company?

She teased me about my French and then paired me with a French lady who had no English, to catch me out. I failed miserably but she translated smoothing out my faux pas. Minerva of the school bench, sweet Sophia.

Peggy’s song must go into Johnson’s next volume along with ‘The Lofty Ochils’, recalling those precious days at Harvieston. I have set it to Neil Gow’s ‘Lament for Abercairny’, proving my devotion. Her cousin Charlotte’s song belongs there too along with the air I got at Inverness.

How pleasant the banks of the clear-winding Devon

With green-spreading bushes, and flowers blooming fair

But the bonniest flower on the banks of the Devon

Was once a sweet bird on the braes of the Ayr.

All it needs is a fiddle and a Neil Gow.

Then back to Mauchline I went to the prying tongues. No more sunlit raptures or twilight tête-à-têtes beneath the shady hills. Just restless cares not knowing which way to turn. Farming is the only thing I know, and little enough at that, but it’s a life that killed my father. Now they threaten to break up what remains of my closest family.

I could not settle to my mind. Should I try again for Jamaica? To stay at home without fixed aim would only dissipate my gains from the Kilmarnock poems, and ruin what compensation I could leave my little ones for the stigma I brought on them. The welcome weans.

Yet I did have my Mauchline belle, my Juno. After the poetic jaunts she pulled me back to herself. What a relief to spend my pent up emotion into her moist warmth. For weeks and months I had been starved, straining at polite intercourse. Sometimes in Edinburgh I went down from Dowie’s tavern in the darkness and had some Cowgate wench, skirts lifted, hard against the wall, for a few coppers. But Jean’s lovemaking was full and open as the hills of Ayrshire, an honest passion, a body made to be caressed and yoked. Often I took her working breasts into my mouth till nippled hard and sunk my member into her passage. Soft belly under taut muscles rise and fall as boats on a swelling sea.

That was country love. Rab o Mossgiel in rut. Dear Jean’s only reading is the Psalms of David, and of course a certain book of Scots poems to which she is devoted.

But Peggy Chalmers will not marry me. Why? She touches tenderly on my feelings, my friendship, my talents, even as she refuses me. But of her own feelings not one word. Her reasons for turning down the ploughman poet? Is she too high for lowly Burns? Her father farms like mine. Too refined for Rab o Mossgiel? We made one happy party beneath the Ochils, conversed as equals, discussed men and women, books and the lovely world. These are the happiest days I have ever known. By Minerva’s native glades and streams. Have I no reason left to hope? What’s wrong with Robert Burns?

She will surely like these songs, the declaration of a poet’s love. And old Tullochgorum’s paid the highest tribute to my Muse. I must copy Mr Skinner’s letter for her. I value his praise more highly than the approbation or disdain of a roomful of Edinburgh’s literati. He too has drunk at the mountain springs of auld Scotia’s Muse. There is a certain something in the older Scotch songs, a wild aptness of thought and expression, which marks them out not only from English songs but from the modern efforts of our native song wrights. We sons of Caledonian song must hang thegither and challenge the jury of fashion. We can lash that world and find ourselves an independent happiness.

I wonder if they have begun to talk about Jean’s appearance in Mauchline.

With Bob Ainslie and Willie. Came home later.

I have seen Mr Miller’s two farms lying prettily by the Nith. Both are up for lease but the ground is sour and the house at Ellisland half fallen down. O for a Horace in the desert wastes.

Passable evening despite my troubles.

After a drink in Anchor Close we went on to Dowie’s. Very private and snug. Smellie was full of some pamphlets from America, newly bound for discreet sale. Some are by Tom Paine, an English Exciseman before going to the Colonies to champion the cause of liberty. By Willie’s lights, Paine has demolished monarchy, for if the power of kings had to be checked by parliaments, how could it be ordained of God? Despotic rule is therefore contrary to natural justice and divine law.

Yet parliament itself in London defers to hereditary principle with benchfuls of m’lords sitting in judgement on the people’s representatives, such as they are. A member of parliament may be elected by thirty comfortably dined men. The purpose of government, says Paine, is to preserve liberty and restrain the will of rulers. Where then the ancient King of Scots? Were they not defenders of our nation’s freedoms? Is government now not tyranny by another name?

The natural right of men, and women – here Smellie raised a romantic glass which we were compelled to follow – is to be free and to have that freedom protected by representation. I believe this from my heart yet my head is overtaken in the race. Where America has gone will Britain follow, or France, or Spain? Bob was very douce. Does he class Smellie’s lectures as philosophy or as sedition? He keeps his own counsel.

Ainslie has no political passion, no inner fire for freedom. The lawyer’s clerk sits perjink, sleekit even, in the courts and taverns. Yet in his mind every mischief buzzes like a byke of hungry bees. No thought too low for Bob to comprehend, no slight so trivial that it escapes the tally. His ever listening ear sips up my nonsense with a sympathetic snigger. Wayward fancies pile one upon another till the crazy tower comes tumbling down. But if blue devils rise, Bob is my perpetual ally, sure defence and sole protection.

It was Ainslie, a few nights since, that whispered Hastie’s Close into my ear. There he claimed gambling, cockfights and other bodily combats were to be had for easy money. Entry should to be petitioned and obeisance made to a Prince of those infernal regions. Don’t ask who, Bob croaked, a warning finger pressed to his pouting lips.

The other two had drunk over deeply to go anywhere except home. But my incapacity for wine left me strangely lucid, light-headed on a cold and starry night. In their stupor Bob and Willie presumed that I was after Cowgate warmth, so I took the narrow passage down, crossed into Hastie’s Close and tapped at the forementioned door. My assurance gained admission to the fringes of a scene of fervour such as Mauchline scarcely boasts. The Prince seemed absent and I escaped unscathed. Bob will want to weasel out the tale, but I can guard this secret for myself perhaps to go again in some idle hour.

No word from Creech. Peggy’s letter expected daily.

Refused. Publication outlawed.