7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

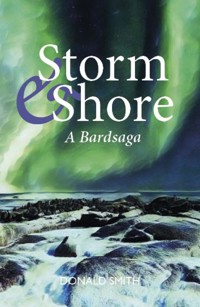

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Commissioned especially for Scotland's Year of Stories, Storm and Shore connects the west coast of Scotland's rich mythological past with the present day. When artist Lucy Salter comes to a remote Argyll coastline she aims to connect with nature in its wild state. Aid worker Dave McArthur is fleeing traumatic conflict. But they have both ventured into a borderland, layered by history, migration and repressed violence. It is a liminal place, storied by centuries of settlement and travel. Yet local tradition bearers, bard and seannachaidh, can channel the past. From these hauntings, a storytelling tapestry is woven from the sea, nature myth and weather. The long roots of our global crisis are laid bare in landfalls, wherein the crucible of Gaelic tradition, creatures of the sea meet the shore.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 206

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

DONALD SMITH is a renowned storyteller, founding Director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre, and an experienced playwright and theatre producer. He was also a founding Director of the National Theatre of Scotland, for which he campaigned over a decade. Born in Glasgow of Irish parentage, Donald Smith was brought up in Scotland, immersed in its artistic and cultural life. Smith’s non-fiction includes Storytelling Scotland: A Nation in Narrative, God, the Poet and the Devil: Robert Burns and Religion and Arthur’s Seat: Journeys and Evocations, co-authored with Stuart McHardy. His Freedom and Faith provides an insightful long-term perspective on the ongoing Independence debate, while Pilgrim Guide to Scotland recovers the nation’s sacred geography. Donald Smith is currently Director of Tracs (Traditional Arts and Culture Scotland), based at the Storytelling Centre.

For Naomi Mitchison

Cailleach nan Sgeulachdan

First published 2022

ISBN: 978-1-80425-060-0

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Donald Smith 2022

Contents

Acknowledgements

LANDFALL

ONE

TWO

THREE

FOUR

Acknowledgements

THE ART OF landscape evoked in Storm and Shore, though not the character of Lucy Salter, is partly inspired by the work of Skye-based artist Julie Brook, who lived for a period of months on the uninhabited Hebridean island of Mingulay. There amidst other works she created fire beacons in the intertidal zone. However any other resemblance between any fictional character in this story and any living person is accidental. Historical figures mentioned are viewed solely through the perceptions of the characters.

LANDFALL

LONG AND SHALLOW and far away; unroll me like a map.

On one side run narrow straits of sea. Wind crested. On the other, sea loch reaches like an extended finger. Making almost an island.

People come here to escape, from whatever you need to escape.

At the top there is a village and sheltered harbour. And to the west on the sea side a landing place.

Below that a wide sandy bay extends, closed off at the southern end by a rocky arm that points seaward. And in that bay an island. Sanctuary Bay. Beyond the arm, on both sides, stony shorelines run below rough muirland.

The cowled ones came here for refuge. Later the drovers made a track from sea to loch, a respite from the cattle boats or fearful salty plunges, water thrashing, eyes distended.

Once the roads were all at sea; this peninsula, the landfall.

No-one has to come this way now.

I am faraway; but sanctuary still.

ONE

GIVING ME SPACE, right. But did they mean this small?

Two wee rooms, and a kitchen that must have been a byre. Everything mucked in together – beast and man.

Hearth deep in the gable; old enough. Walls like a fort, stone-flagged floor. It’s a new roof though, and all mod cons installed, even a hob. In case the aliens land, like me.

Himself from the village does not seem to approve anyway. Tall, upright old fella, looking me up and down like a dubious recruit. White beard, beak of a nose and eyes from the sea. Maybe the owner.

Inspection complete, Mr MacLean leaves me to it. Well, I can find him at the landing stage beyond the village, if necessary. That famous Highland hospitality.

And another first night for me. Nothing new there, though strange in the stone of it – the age like home. But definitely not like there. Nothing like there. So unpack; eat tinned food, hob-warmed drink, turn in early to bed hopefully.

One fifty-eight. Observation dies hard, even with the sweats.

Much the same: huts roofless, thorn enclosures smoking, clothes and pots scattered, everyday trashed. In this version, I seem to be counting, turning them over to identify age and sex. More and more. Someone’s shouting to leave, go quick, quicker. One brightly coloured figure, stretched in a doorway. I turn it, pulling; her arm comes away in my hand. The head shoots up and falls from her shoulders. Running on the drop, suddenly awake.

Somewhere light seeps in, more than the clock. Drag myself to the window and stare out. Starlight, layer after layer, into night, till my head swims and subsides. No sky have I seen like that since leaving Africa.

Pull on clothes to go out but realise I am shivering. Back under the covers, turning between fitful sleeps. Another test failed. Counting towards another day.

I come to with a dry mouth, and even the tea tastes rancid. Sooner I can cut back on sweeties the better.

Bit shaky on the pins, but get out to try the air, get my bearings. But don’t look; there’s no need, no warning signs, no danger. Still.

Listen; shut your eyes and listen. Gulls wheeling. Terns somewhere. Feel some wind on the cheek. And waves plashing on the shore, like you could wait forever on the next one. Nothing. Nothing else. Something chugging – boat far out. Fishing maybe beyond the bay, on an open sea.

You can look now. Take the view west. Islay, Jura, Tiree, Ireland, and all the waves between. So I’m told, but today everything’s shifting grey. Melting, merging somehow. Irish air.

Except down there, right below, the shore – my beach. A wide sandy strip runs clear as a bell to the rocky point, enclosing its little island. That’s the spot for me, down to the sea, all laid out beneath.

My first wee stroll.

Here I go then. There’s an old yard behind the cottage, cobbled. ‘Causie’ they used to call this at home. Few tumbled walls, then the path. Left to the church further on, which needs checked out; right back to the village; left and hard right for the shore. It’s like spaghetti junction for sheep. Not a human in sight. The legs are working fine, just watch the feet shifting one in front of the other.

Few last hummocks, then a drop. Mini-cliff tucked in on the edge; wee surprise for the unwary. But not for me, not at all. Wait though, there’s steps, aligned with the path; they’ve been cut into the rock. How long have they been here?

Well-worn footsteps. I am on the sand. And a smirr of fine rain blows in. First day of the holiday. Take it on the cheek, cool.

Wan sun rinsed out by six o’clock. Light slants onto beach, into tent and cave mouth. But this rising is obscured, aborted by low cloud, riding in on a light breeze as the tide goes back. Grey... blue... watercolour black.

A jacket is needed on top of my trousers and jersey to walk the tideline. Boots as well.

Plastic debris, a nylon net, rope, wood, washed out and smoothed down. I gather one piece of timber striated and blackened at the end as if it had been burnt. No fires aboard ship surely. Observe, don’t imagine.

Today’s tasks:

Sketch the island under cloud – might become a series in gouache.

Photograph the sheep’s skull uncovered yesterday at high tide. What interventions might suit?

Record the variations in sand cover... like hour glasses?

Go back along the point to observe the different kinds of seaweed on rock. Check tidal deposits.

May see more seals. How do they fit into these cycles? Are they an intervention?

Must go to the shop and get dry matches. Call in at Mr MacLean’s for any post. Return along the north beach to my bay and view the declining light from an indirect perspective.

It is surprising how quickly the evenings are already earlier here. Should I go to bed earlier as well to maximise the daylight hours? How many more hours of sleep can I absorb? And stay alert.

Must allow more time to record and reflect. Expand this journal. The clues are here as well as out there – all in the looking.

The key is beneath the mat. The latch is fastened on the outside of the inside door. The nurse knows where to look if she needs to gain admittance, and I am still away.

She cannot be harming herself in any way she might try. The delivery van is late again with the boats all landed, and a fine catch. Why should the fishermen have to pay for their mistakes if the crabs and lobsters are not in their best condition? The estate has its landing fees and there is my commission. That may be the van now. Let them sort it out amongst themselves.

One day there may be nothing except pleasure craft here, moored at the lochside. What shall I have then but the croft? Poor land.

Ewan’s sheep are over the brow of the hill. They like to come down on the old rigs for the grass, but not today. And there is no sign of the lame yow. She is broken, and the crows will be having her. I have no need now to be working this ground. Ewan will give me a lamb or two. To think on the people struggling up here from the shore with creels of seaweed to mulch these stones. You can see the nettle beds yet. They set down their loads long since, and lay down in the earth, or left for other lands. Leaving us to remain.

There now the lark is rising. You think she would be used by now to my walking. There has been no-one on the ridge today. Except the fox, he has left his mark. On patrol, watching his chance to kill. He will be home now over the brae. Rutting with his bitch.

The clouds are off the sea today, carrying a soft cover of rain. Enough, though, to put the beasts on the lee side.

But the artist lady is out at her scavenging. She tells me that she is after anything the sea will give. Dulse, tangle, driftwood, torn nets, the broken ends of fish boxes. They are all plastic now. Perhaps she is not wholly well in her own mind, yet she appears clear enough. She looked me directly in the eye when she asked for permission to camp by the cave mouth. Strange for a woman on her own, but there are letters and phone calls in the village.

Next she will be meeting our new Irishman. Someone else made the booking for him, or I would have realised ahead of the time. Why is he coming here with that name on him? Perhaps he is ignorant of his own kind and their history.

Afternoons are worst when the wee jobs tail off. Too early for the telly, especially if you don’t have one.

Not having a drink either, not yet.

Radio Scotland Newsdrive, 4.30m, Radio Four PM, 5.00pm. Foreign news to be taken in small doses.

Electric bars switched off in an empty fireplace. Only September after all. Scottish September.

Woman on the beach seemed interesting. But too busy to talk, or unwilling. An art project of some sort – personal thing, cutting off other questions, as if art wouldn’t be my bag. Has me down as fisherman, or lonely alkie. First impressions. Like I had trespassed on her private shoreline. Fair enough. It’s all about territory, so they say. I’m here now as well. For a while anyroads.

Could spread everything out on the kitchen table, dining table. Not required otherwise. Space for notes, briefings, photos, maps, e-mails. All packed and ready.

Or stash them in the press for a rainy day. Neat piles folded like sheets. Not why I’m supposed to be here, but is there anything else to do?

A single-storied house, white harled, sits above the landing place. This is the one. Only these bouldered outhouses remember when people were forced down from more fertile ground to the sea. And before that.

No-one about. Pass through the first door and raise the latch. A bowed white-haired figure by the hearth. Smell of old-fashioned peats. The white hair is cropped to the neck. The skin is brown-weathered, folded. Round shouldered in a cardigan she sits and stares at the smouldering embers.

A kettle hangs above the fire, gently beginning to steam. Is this her way of inviting me, calling me in? I know I shall be made welcome in her place.

Better out even if it is raining. Soft like autumn on the Foyle. This path seems to run all the way along the spine of the ridge. North to the village with branches off to the beach. Due south, through sparse conifers to the church and headland beyond. End of the line.

Just getting my bearings when old MacLean comes stalking out from the trees. Is he spying on me? Paranoia.

Hopes I have everything needed for my comfort? No problem, short of any normal neighbourly chat. Hard to discuss the weather when it’s so clearly in your face, for the next while anyway.

His eyes are light grey, or some kind of blue, cold and piercing like a hawk. Not much round here these lenses miss. Then he marches off – sentry on his beat, periscopes revolving. Thinks the Russians are still coming, or the Taliban. No native rebels anyroads, not now they have their own parliament, their own gripey wee Stormont. Hell mend them.

What’s her highness of the beach up to? Check it out from the top of the bank; no call to be interrupting at this late stage of the day. Nearly time for refreshments.

Does she actually sleep in that wee tent? Trust someone to drag a tent into it. Sand everywhere, but not that kind of sand. Bloody hell, with not a drop to drink.

The island stands out in focus, very clear compared to the soft grey forms behind. But when you begin to sketch, you realise that is a trick of the light. All the edges are blurred to differing degrees. It would work for watercolours or a crayon, not acrylics.

I set off back along the beach towards the point which MacLean calls the seal rocks. They form the southern end of the bay, as if at one time they reached out to touch the island. Now the sea flows in forced by a strong current between the big islands and this peninsula. Nearly an island. Depending on the tides I suppose.

And those tides bring in the boulders, casting them up even on the southern side of the bay. I don’t understand how that happens unless the tides spiral round. Hidden strength and power.

To a casual eye, the beach merges imperceptibly into a rocky shore, that then piles cumulatively, erratically towards the southern point. But I only saw that properly today, seeing for the first time. There is a distinct frontier, a boundary of stones which marks the transition. Looking and not discerning.

First, I sketched it rapidly on the ground, trying to capture the actual moment of perception. Then I photographed the boundary from a variety of angles, near and distant.

Next, I started to build a mini-wall, a partial divider on one section of the beach. As if the Romans, or the Celts here, had constructed a fortified frontier; then time and weather had broken it down, leaving only intermittent sections standing. I used broken boulders from higher up, where they pretend to have always been stones. I am layering like a drystone dyker, or a medieval mason working from rough foundations.

Finally, I sketched and photographed the wall in its unfinished state. These images could be the basis of some paintings relating the traverse textures of the shore between sand and stone, to the up and down tidal flows. You can see that in the debris or the sand patterns though only for a short time as the next movements take hold. Unceasing natural energies, which everything from alluvial grains to monumental rocks contain. The passage of time but also cyclical, recurrent.

Or it could be a cultural energy as if the whole landscape is a broken-down form of history. Big words – keep focussed on the work.

This has been a productive day. I am moving closer to the patterns I want to reflect, to keep pace with. A bit closer. As I went to-and-fro with my stones, I could see more seal activity on the headland. New arrivals perhaps following some pattern of their own.

So much to understand. I am putting a step into the dance, letting the mind go.

Darkness over the land. Below the starlight speckled surface of the sea, the country of seals. Finding the depths, propulsing tirelessly through undersea glimmer, bulls journey to their ancestral breeding grounds. Remote, sea-pounded outposts.

For now, cows still gather, shuffling and moaning on more sheltered outcrops, the wide arms of western bays, waiting to birth their blood-streaked pups, nursing and nuzzling them into the salty waves.

Amidst near islands, last year’s brood dive and fish in unbroken abandon.

In distant seas the great grey bull turns towards Seal Rock.

And I am pulled back. The time is coming, if only I can remain, waiting.

‘Morning, how’s things today?’

‘Fine thanks.’

Brown on fair skin. High cheekbones.

‘Bit fresh last night was it not? Are you able to sleep in that wee tent?’

See the green eyes.

‘It’s ok, quite comfortable.’

Still wrapped up in an anorak and two rugs. Hair pulled back tight under a beanie.

‘The wind would keep me awake. I don’t like that noise when it sucks the canvas back out – vrrump. Then you lie there waiting. You know it’ll whump back in any moment.’

‘How do you know that?’

‘I lived in tents for a while with my work.’

‘If the wind wakes me up, I go out to see what’s happening on my shoreline.’

‘Your shore?’

First hint of a smile. I might not be Count Dracula.

‘Well, I seem to be looking after it for now anyway.’

‘Fair enough. What happens but if a really big gale gets up?’

‘I can retreat into the cave there. It’s completely sheltered.’

‘How come?’

‘It twists round into the bank. Look, I need to be getting on.’

‘I saw you writing as I came down.’

‘Just my workplan for each day.’

‘Do you not record your observations?’

‘Sometimes.’

‘Things round here seem to shift from minute to minute.’

She looks as if seeing me for the first time, then turns back to her daily task.

‘Right then, I’ll maybe come around later.’

Off along the sandy beach to see what the tide’s brought in. Routine, discipline is what this boy requires. Finding an order between these tides. Is that what she’s after with the art thing? Jesus, forgot to introduce myself. Don’t even know her name, numptie. Not even half your father’s son.

Might see a bit of sun today though. Stretch out the old pins. Listen to those waves gurgling in, lapping out. Those waders know their business, howking out breakfast beneath screeching gulls. Go on man, get some of that air into your lungs and blow it back out through the wind.

Maybe we could try some breakfast ourselves.

A struggle to get going this morning. Woke at three o’clock with wind whipping the canvas, and cold. Forced myself out and was rewarded by real waves breaking. The sound of course, but also the strange whiteness of foam catching the light of a crescent moon between clouds. Weird cries on the wind like signals of distress. Maybe seals disturbed by the big sea on their rocks. It must be much rougher on the point.

What I need is a studio, to go and paint without interruption, laying on blacks and blues as the bed for all those gleams, glimmers, glints. Instead, I was driven back into the tent, unable to get warm. Shivering with the cries. Slipped eventually into sleep and woke late. Morning calmer, but still cool.

Jobs for today:

Check my tide wall for damage – is it being reclaimed?

Walk along the beach to sift the debris – spindrift from last night’s wind. Any new seaweeds, mix of dulse and tangle. The birds seem to be at the same sorting out, but I can’t tell one species from another.

Interrupted next by the man from yesterday. Irish, Northern Irish by his accent. He must be the new holiday let in the croft house, but the first one to take any interest in me. Polite or over interested – in art? Looks a bit worn, as if he has been ill. Eventually he totters off along the beach leaving me alone. The beach is visible from the croft but not my tent or cave.

Change of tack. The island is in clear focus this morning – grassy humps edged with rock like a bald head fringed with hair. Waves breaking white. Do a series of sketches tracing that oscillating image, yet somehow rock constant, always re-emergent, resurgent.

Eilean na Cleirich, says Mr MacLean, Island of the Priests. Can it ever have sustained life? Seabirds yes but tonsured monks? Only in extreme fast or penance. Maybe they were artists of their age. Clarity of eye, austerity of soul, and in their stone cells they lit a fire to preserve some spark of warmth. Redder than calor gas can offer. Still, it is a germ of heat.

Time to brew a restoring cup and set to work.

This is a day with summer still in it. The tourists can be having a fine view out to Islay and Jura, and to Ireland if they go high enough on this ridge. They love their views, like picture postcards. But they see nothing.

Even our young visitor from Ireland is on the beach today. He does not look well. I am thinking he might have cancer and has come here to recover from the chemotherapy. Pumping the poison through his body, kill or cure.

The marker cairns have crumbled so you would hardly know they had ever been. Coffins carried along to the burial ground and at each resting place another stone. Cairns of memory, for the old people. The only one remaining is where the path meets the new road up for cars. Funerals come yet, and that foolish young minister from Glasgow with his keelie ways – outdoor services and picnics in this of all places. Clambering over the stones without knowledge or respect.

There was a whole village here, clustered round the church. The traces of each house remain, and the big hearths at the centre. Till the killing and burning came on them. No-one remembers now. Though I remember.

A storyteller without listeners is not worthy of the name.

The cross they make so much of shelters in the chapel, so that it will not erode further. They are mistaken in naming it Abba’s Cross, for it was raised by the sons of Artur Mac Aedan, a prince of Dalriada. He was slain fighting the Picts, but later his descendants settled here around the church. Abba was earlier, before the high cross was raised. Yet he was not the first to use the headland. He came from Ireland seeking the place of his resurrection and did not find it here. There was some trouble between his community and the house of the women by the rock well. So the tradition has it, and he took voyage to the north, the ends of the earth.

Perhaps he had a gift of prophecy, for there were only a few years left before the sea wolves nosed their longships onto the beach. The folk fled at first sight, but not the cowled ones. The raiders scattered out from their landfall loping up onto this ridge and heading towards the enclosure. The monks gathered in their chapel like lambs dressed for the slaughter. And the altar ran crimson from their wounds, the blood of Christ. They had gained their prize, the red martyrdom.

Without a second glance those savage men bundled the sacred treasures, chalice, patten, candlesticks, into their sacks and hurried back to the ships. They met no resistance for none was prepared for such merciless assault, the unexpected fury as if from the depths of hell itself, so swift and deadly and cruel.

That was the beginning of the killing times, always a price to be paid, a sacrifice offered or taken by violence. The pattern of this place, endless giving and taking, land and sea. Yet the Women’s House endured, their tradition long lived.

Our artist, Ms Lucy as I must learn to call her, seemed most interested in that, and in Abba’s Island in the bay. Perhaps she herself has come in search of sanctuary.

Only the most recent graves are tended here now. The memory of those times buried as if they never were, as if sunk in Brigid’s unfathomable mind. Perhaps such forgetting is for the best, who knows?

I think I shall not go as far as the headland today. I can see the sun on the stones, and that is enough.

Sat myself down and went out like a light. Put it down to sea and sun. Or wind. All the way to the landing place, up to the village and back along the ridge. Alpine circuit.