20,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

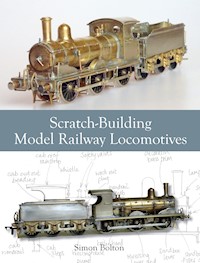

Have you ever dreamed of being able to make a beautiful model locomotive from scratch? Do you have a favourite locomotive that you would love to reproduce in model form? Are you itching to start such a project and feel you need a helping hand? If so, this is the book for you. Using step-by-step text and illustration, this new book demonstrates how to construct a model of a pleasing J15 class, 0-6-0 steam locomotive in 00 gauge. It also explains how models of other locomotives can be built by adapting the methods covered in the book. Alternative options for chassis construction, other gauges and scales are considered as well as how to build a simple diesel locomotive.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Scratch-Building Model Railway Locomotives

Scratch-Building Model Railway Locomotives

Simon Bolton

THE CROWOOD PRESS

First published in 2014 by

The Crowood Press Ltd

Ramsbury, Marlborough

Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

© Simon Bolton 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 769 4

Dedication

This book is dedicated to Paul for his amazing help with organization, editing and laughter.

Acknowledgements

My thanks to the following who have kindly allowed me to include their excellent photographs: David Coasby, Paul Winskill, Steven Greeno, Gordon Gravett, Benjamin Boggis, Paul Macey, Keith Ashford and Maurice Hopper.

I would also like to thank all those society members and website forum contributors for their assistance and kind comments.

And finally, thanks to my father for having a lathe in the front room as I grew up.

Disclaimer

The author and the publisher do not accept any responsibility in any manner whatsoever for any error or omission, or any loss, damage, injury, adverse outcome, or liability of any kind incurred as a result of the use of any of the information contained in this book, or reliance upon it. If in doubt about any aspect of scratch building model railway locomotives, readers are advised to seek professional advice.

CONTENTS

DEDICATION AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PREFACE

CHAPTER ONE: WHY SCRATCH BUILD?

CHAPTER TWO: WHAT TO BUILD?

CHAPTER THREE: WORKING WITH TOOLS AND MATERIALS

CHAPTER FOUR: SOLDERING AND JOINING METALS

CHAPTER FIVE: THE CHASSIS AND COUPLING RODS

CHAPTER SIX: GETTING YOUR CHASSIS RUNNING

CHAPTER SEVEN: THE LOCOMOTIVE FOOTPLATE

CHAPTER EIGHT: ABOVE THE FOOTPLATE

CHAPTER NINE: THE BOILER, SMOKEBOX AND FIREBOX

CHAPTER TEN: DETAILING THE LOCOMOTIVE

CHAPTER ELEVEN: THE CAB INTERIOR AND ROOF

CHAPTER TWELVE: BUILDING THE TENDER

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: FINISHING OFF

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: EM-GAUGE CHASSIS

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: DIESEL BUILD

CHAPTER SIXTEEN:ON-GOING PROJECTS: OTHER SCALES AND TECHNIQUES

FURTHER READING AND RESOURCES

INDEX

J15 Locomotive 7564 at Sheringham station on the North Norfolk Railway.

J15 scratch-built model.

PREFACE

For the beginner, scratch building can seem a daunting prospect: how do you start, what tools do you need, will it hurt? For me, scratch building has opened up a world of possibilities and creativity, allowing me to practise skills, collect ideas and methods, and come up with some of my own. I’ve been inspired by the enthusiasm and helpfulness of the people I have met through this project; they have been incredibly helpful and keen to share their time and expertise.

Being able to build the locomotives that I want and to be proud of the results is very exciting, and it is this excitement that I want to share. The aim of the book is to inspire the beginner to take up his or her place at the dining-room table (or work-bench) and begin to scratch build. I have chosen a pleasing locomotive (the J15) to scratch build, which, at the time of writing, is not available as a ready-to-run model. I have chosen OO as the main gauge to build in, as it is the most popular and accessible format. There is excellent trade support for scratch building in this gauge, and a great deal of online advice.

The book is structured with the aim that you will be able to scratch build a OO-gauge J15 locomotive following the stages set out. I have included my own drawings, with some slight simplifications to the dimensions to make life a little easier, lots of prototype photographs, sketches, and step-by-step photographs. To ease the process further, I would urge you to acquire a relevant set of scale drawings. However, it’s not all hand holding: as the book progresses you are invited to make your own decisions regarding construction and detailing. Descriptions of different methods available and avenues for further research are given.

Like many skills in life, learning to scratch build is an on-going and highly enjoyable process, and I hope that you will be able to take what you can from the book and, most importantly, enjoy yourself as you do.

ABOUT ME

I have been scratch building model railway locomotives on the kitchen table since my early teens, and as my skills have improved, so have the kitchen tables. I have taught both adults and children for many years, and firmly believe in the positive effects of making things, crafting objects, and the pleasure to be gained from creating something for yourself.

I would be very pleased to be contacted with any questions about your scratch building or to hear about your progress. Please go to my website for contact details and further resources: www.artfulengineering.co.uk

Simon Bolton

CHAPTER ONE

WHY SCRATCH BUILD?

DEFINITIONS FIRST

My understanding is that scratch building, within the terms of model railways, is the production of models by choosing and using raw materials, tools and skills that you find appropriate and that suit you. Scratch building is a wide-ranging term – in fact, as far as I’m concerned, it can mean anything from modifying kits and ready-to-run items to making the component parts of a model, right up to producing your own wheels, motor and fittings.

WHY DO IT?

I really enjoy scratch building. I enjoy making something that wasn’t there before, I enjoy having things that are a little bit different, and I get an immense feeling of satisfaction from having made something myself. It means becoming completely immersed in a project that involves problem solving, and the acquisition and utilization of skills to produce a tangible solid object. Moreover this is believed to have beneficial effects on our mental health, in that clearing your head of extraneous worries and concentrating solely on the task in hand is very good for you. So if nothing else, the model railway hobby is an economical and pleasant form of therapy.

Scratch building, then, is the perfect fit for escaping the everyday trials of life and refreshing your mind for new challenges. And as a by-product, you end up with some beautiful models.

You may, of course, find the challenge difficult to handle and be tempted to hide your miniature offering in the back of the cupboard. This is normal, too; the most effective learning can come from making mistakes, picking yourself up and carrying on. This is literally the case in learning to walk: did you give up, vow never to do it again, and go off down to the pub in a huff? No, you got back on your horse and drank your milk. Soldering is like that (the pub just helps).

One of my earlier projects, a Great Western 2-4-2 Birdcage tank loco in 7mm scale: almost completely scratch built bar the wheels, motor and fittings – and am I proud of her!

CHOOSING A SUBJECT

I’m going to describe how I scratch build model locomotives starting with simple methods, and then introduce complementary techniques, which are arguably more complex. The more practised you become at something and the more you challenge yourself, the easier it becomes. Scratch building may seem daunting at the beginning; however, it soon becomes compelling and you’ll wonder why you were wary of starting.

The wide range of approaches suits me: I’m not an engineer; I buy ready-made wheels and motors; and I also buy or commission detailing parts such as chimneys and domes. I’m not a fast worker (almost glacial in fact); I’m very meticulous (a Virgo apparently), and I tend to plan most projects in my head as I go along, with the occasional foray into sketchbooks or on to the backs of envelopes.

Locomotives are the subject of this book as they have particular challenges and are generally more complex than other forms of rolling stock, such as coaches and wagons. When you can successfully build a locomotive you won’t have any trouble with a fish van.

There is now an enormous and still growing choice of superb ready-to-run models in the most common OO gauge and increasingly on either side of the size spectrum in N gauge and O gauge. Paradoxically, this abundance may be decreasing the availability of kits as manufacturers are forced to consider more rarefied prototypes, which may not sell in sufficient bulk to be practicable. There are probably always going to be some locomotives that are not going to be commercially available – at least, not in the near future.

Building something allows to you to produce exactly what you want. It is generally cheaper than buying an off-the-shelf model, especially if you don’t include the construction time (and that’s the fun bit). You can have any loco you want from any time period or railway company. You could make a unique model of a loco on a specific date exactly as in a treasured photograph. It may be a loco that you spotted, or one that you rode behind and one that means something to you emotionally: an evocative and tangible memory in three dimensions.

You might want a static ‘museum’ specimen with everything included: all those bits and pieces underneath and inside that make the real thing work. Or it might be an imaginatively fictional ‘freelance’ model, not to mention the occasional ‘Thomas’ to enthral the younger generation.

If you’re after something quite different you could try one of the ‘rarer’ gauges, such as 3mm scale and S gauge. These have their own particular advantages: 3mm has greater heft than N gauge and still takes up less space than OO gauge, while S gauge goes the other way, fitting nicely between the size and weight of O gauge and the more compact OO gauge (and in imperial measurements at a size ratio of 1 to 64).

The Lady Armstrong, an Armstrong-Whitworth diesel electric shunter that provided a large proportion of the motive power on the impecunious North Sunderland Railway (when it wasn’t broken down and replaced by a local taxi service).

There are all the narrow-gauge variants, too – or you could even have a gauge or scale all of your own. A particularly beautiful example is the layout Pempoul modelled by Gordon and Maggie Gravett to a unique scale of 1 to 50 – and a French prototype to boot.

SCALES AND GAUGES

Just to clarify, ‘gauge’ normally refers to the distance between the rails, a reduction of the full size 4ft 8½in (1.44m). For example, OO-gauge track has a gauge of 16.5mm, which is slightly narrower than it ought to be. ‘Scale’ is the ratio by which the real thing is reduced to model size; again in OO this is 4mm to 1ft (30cm), where each foot of the real thing is represented as 4mm on the model – which makes OO track just a little over 4ft (1.2m) wide.

In S scale everything is divided by sixty-four, and you can have a great deal of fun immersing yourself in scratch building.

As I mentioned, OO gauge is a historic compromise of 4mm scale for everything but the track, and consequently the width apart of the wheels. One of the reasons often cited for this is that it was difficult to fit the bulkier electric motors of the earlier twentieth century into locomotives at a scale of 3.5mm/ foot, or HO (half the size of O gauge at 7mm/foot). So they kept the track at HO and made all the rolling stock a little bigger.

Maurice Hopper’s lovely little S-scale layout St Juliot The audience are watching the author (standing) struggle ineffectually with the three-link couplings.MAURICE HOPPER

This curiosity has promoted the growth of various complementary gauges that aim for a progressively more realistic appearance. EM stands for 18.2mm (it was widened a bit from 18mm) between the rails. The even more precise gauge of 18.83mm can be found, championed by such societies as Scalefour. And when I say championed, people can be very enthusiastic about, and protective of, their particular choices in all aspects of railway modelling.

APPROACHING SCRATCH BUILDING

This book describes the more traditional ways of construction by cutting and shaping materials, generally by hand. There are new and thought-provoking ways to produce models, and resin moulding, laser cutting, computer-aided design and 3D printing are becoming increasingly commonplace. It seems that the model railway community is often amongst the early innovators, and embrace new ways of doing things – and there is a great deal of information available out there if you find yourself drawn to these exciting developments.

The main emphasis of this book is to provide a step-by-step guide to building a locomotive in arguably the most popular gauge – OO gauge (4mm scale) – and to briefly describe techniques from other gauges/scales. Virtually all the approaches lend themselves to any of the scales, though there are quirks that are more applicable to some than others.

I have built up my skills through practice over the years, choosing methods from books, society journals, magazine articles and, more recently, internet forums. Joining a club has allowed me to pick people’s brains, and I have learned a lot from visiting exhibitions. There are usually excellent demonstrations by skilled modellers who will happily show you the things that work best for them; you can explore the differences and work out what is best for you.

The processes I describe in the book are the ones that work for me. I use simple tools, and haven’t got a lathe or milling machine. This is not because I don’t want them: at the moment I just don’t have the room. I am very much looking forward to acquiring some hefty hardware when there’s enough space for it not to interfere with domestic life – but until then it’s the kitchen table.

Historically, model railways were built (out of necessity) from whatever materials were cheaply and easily available. People were happy to bash something beautiful out of a biscuit tin with a hammer and a pair of pliers – including the drive mechanisms. The necessary skills were routinely taught at school (if you were a boy…), and it was an everyday occurrence to watch your granddad whittle something useful for the household with a selection of tools from his well stocked shed. People fixed anything that broke. These pleasures and skills, and the confidence to use them, are now not as commonplace.

An inspirational scratch-built locomotive by Gordon Gravett running on Pempoul – a superb example of what can be achieved with practice.GORDON GRAVETT

Happily now there is a roaring trade in detailing parts available from small manufacturers, and the practice of buying motors and wheels is almost ubiquitous and equally well catered for. There is also a resurgence in old-fashioned manual skills and creativity, which is reflected in the continuing interest in model railways. You only have to look at the wonderful examples of real-life scratch building, the steam locomotive ‘new builds’, to see how railways can still capture the imagination.

MAKING A START

Before you take the plunge you might want to get in some practice: perhaps soldering together an etched kit or modifying a shop-bought locomotive. Whilst I would recommend that you do this (I did and still do), it is not essential. If you are scratch building you are not going to make a mess of an expensive kit or ruin your favourite r-t-r (ready-to-run) loco. If you do make a mistake, and you will, you can dismantle the relevant bits and start again, or throw away a wonky component and make a new one. I have boxes full of rejected bits and pieces, which is frustrating and educational.

The chief motivation in deciding to build your own model may well be, as it is for me, the sheer pleasure of construction. I can sit and admire a half-completed model or set of pieces with great satisfaction as I work out how next I am going to put them all together. However, if you find yourself in difficulty I would advise you to step away from the work-bench and have a walk. If you’re good at imagining shapes in 3D, then a tricky piece of construction may magically resolve itself inside your head while you’re happily loading the dishwasher.

I find acquiring new skills, or making steady progress in existing ones, very rewarding, not just in modelling but in all walks of life. And many of those are transferable to modelling: measurement, imagination, patience, perseverance, a positive attitude and a pair of reasonably steady hands. There are no barriers to age or sex. The number of children at exhibitions seems, happily, to be holding up steadily, and more and more women are glad to demonstrate and discuss their modelling techniques in public. In fact I find that women are generally far more able to discuss things.

As a teenager I always loved the ‘how-to’ features in The Railway Modeller, and I hope that this book will do for the reader what those articles did for me. Latterly I have found magazines such as the Model Railway Journal inspirational. Seeing superb workmanship shouldn’t put you off – equally, listening to that little voice over your shoulder telling you that you’ll never get there won’t help either. You can aspire and build and be very happy with something you’ve made, and as you learn from your mistakes you’ll be even happier.

It may also be one of those tailor-made opportunities for you to sit down with your son or daughter, niece or nephew, spouse or concubine, and learn together. Children enjoy the creative process just as much as they did in the days of Meccano; look at the ongoing popularity of Lego or the proliferation of snowmen and sand-castles whenever the weather conditions allow.

There are specific skills that you will need for scratch building locomotives, and there’s no time like the present to get hold of a soldering iron and a piercing saw and wave them around in a meaningful fashion. These are the hardest things you’ll have to tackle, and like anything else, they take practice. You will have to roll with the blows of the occasional disappointment and disaster – though each new challenge becomes easier with familiarity. Actually, the most catastrophic scratch-building catastrophe is that of dropping your much loved model on to the floor. And you can do that just as easily with something straight out of a box.

CHAPTER TWO

WHAT TO BUILD?

Scratch building enables us to have a completely free choice of what we want to model. It also requires us to know why we want it. You might set your heart on an example of an unusual locomotive, or maybe decide to take up the challenge of producing a specific member of a class. There are lots of different locos out there, and the more you look, the more you will find: oddities, experiments and one-offs, and stuff for which there is little information and for which you’ll need to dig around in obscure books and follow murky internet trails.

The smaller scales allow smaller layouts in restricted spaces, or they provide the opportunity for wide, sweeping lines with long trains in open countryside or urban settings. Larger scales take up much more room. The bigger you get, the more detail you might want to include and the fewer models you’ll need to fill the available space. Do you want a static model in a display case or something that can nip round your garden in the rain?

The locomotives in this book, unlike many of the real things, are propelled by small electric motors, so if you want any other form of power (clockwork, battery, radio control, live steam) you’ll be able to find further information in all the other books, magazine articles and the internet that are out there.

Finally, how much detail do you want? Can you get parts or is there a kit?

MY CHOICE

I have chosen as my main example an LNER J15 (formerly GER Y14) in 4mm/OO gauge, as there isn’t a readily available kit (as I write) and no current ready-to-run (r-t-r) model – though no doubt there will be by the time you read this sentence. The J15 is a beautiful British 0-6-0 inside cylinder tender locomotive with a low slung, rather cat-like demeanour. Long-lived and numerous, they tackled both goods and passenger trains over a large geographical area, from tiny country branches to main-line services, ranging from the wide open spaces of East Anglia to the wilds of Scotland.

It has no outside valve gear, and all the mechanical excitement carries on unseen between the frames, which makes things very much easier. The loco and tender are not encrusted with rivets, just enough to add texture, and there is a reasonably small number of quite charming variants and modifications. The tender also allows for some slightly less mechanically involved practice in scratch building.

The LNER J15, a striking example of Victorian locomotive design.

Alan Gibson, as well as occasionally producing a kit of the J15 in 4mm and 7mm scales, complements these with many excellent castings of the bits I don’t generally like to make (and some of the ones I do). These bits are an absolute boon to the scratch builder both new and experienced; they are also quite easy to get hold of from traders at shows or internet websites, and you might be able to pick up some useful odds and ends from swap-meets and eBay.

Wheels and associated mechanical parts are straightforwardly available, and the biggest problem to tackle, I discovered, was fitting a motor into the rather petite boiler. However, this was helped by modern small motors being highly efficient and powerful.

I have a number of wonderfully atmospheric prints of J15s in service, particularly No. 65447 on the East Suffolk line in early BR days, one I knew well growing up there in the 1970s. There is also a glorious example, No. 65462, preserved on the North Norfolk Railway. A model of a J15 ticks all the boxes for me: comparatively simple to build, lots of easily available information, a real one to take detailed photos of, an emotional connection, and just the thing for my (long) planned model of Saxmundham station. And I already had a lot of relevant literature cluttering up the house. A perfect place then, from which to start to scratch build a locomotive.

However, if you are not completely enamoured by the J15, there are plenty of very similar designs of 0-6-0 tender locos from many of the other railway companies that you could attempt instead, using exactly the same techniques. Or even something completely different? If so, do you have suitable photographs? Is there a preserved example? I’m continually surprised by how many steam and diesel locos there are in preservation in the UK – and was also alarmed to discover that my favourite diesel, the North British Class 22, is not amongst them. If you are a diesel fan, Chapter 15 looks at a scratch-built example and should be of interest. (A word of warning regarding a preserved loco: there may well have been necessary or unexpected changes throughout its life in preservation, so take care to look at original information as well.)

I must add that my life-long infatuation with all things Great Western has been almost overturned by the many splendid locomotive types that I have uncovered whenever researching away from home. Do take the time to look beyond your primary interest, as there is plenty out there to take your fancy.

SOURCES OF INSPIRATION

I take great pleasure in the process of collecting photographs and articles. I’ve spent ten years accumulating them for a projected 7mm layout of Culmstock station on the Culm Valley line. I’ve got folders of the stuff and am still finding new things. eBay is a very good (though sometimes expensive) source of photographs. The internet of course can be very helpful, particularly – and rather ironically – when unearthing obscure book titles and magazine articles.

There are many companies advertising in magazines and online who have archived a wealth of railway images and will supply downloads, hard copies and slides. Most of them provide printed catalogues, or you can search and order online. Locomotives Illustrated and similar periodicals are great for historical information and a good range of photos, while old modelling magazines are excellent for more esoteric drawings and information. The number of fine quality books with superb illustrations is expanding, and despite the growing distance in time, interest in the more obscure nooks and crannies of British railway history seems to be building.

The libraries of many model railway clubs are packed with archival gems, and you can spend many happy hours rooting around in them; and it is still possible to persuade your local library to order books for you. If you are very fortunate you might come across something like Yeadon’s Register for your choice of loco; I have the volume that shows virtually every J15 at various times during the long life of the class.

A selection of the printed material I collected for the J15 build – even more stuff is on the computer.

PLANNING AND RESEARCH

There are many different ways in which you can prepare for your build, although the amount of research necessary for the completion of a successful locomotive model is quite subjective. Some people are content with a good drawing and a couple of photos of their chosen class of loco – or even just the one photo.

PHOTOGRAPHS

You can take numerous digital photos if the real thing is on hand, either with a clear idea of those parts and details in which you are interested, or just so many that what you want is bound to show up. It is almost obligatory that something important ends up just off frame or masked by smoke, or by the crew of the loco or another photographer with their copious family standing in front of you.

It is quite difficult to find photos of your particular loco in pieces, either when being built or repaired, or crashed or broken up, and these are invaluable when you do. In the case of the J15, I still couldn’t quite see how the smokebox saddle was shaped until I found the photo (below) in the magazine Joint Line, the house journal of the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway Society who own the only preserved example. In fact I managed to contact the photographer, Mr Keith Ashford, who is overseeing the J15’s current rebuild, and he kindly supplied me with some invaluable photos for this book.

By the time this book is in print, she should be back on the rails and you can go and see her in Norfolk. If not, you could contribute to the fund to rebuild her. I’m very hopeful that I may soon be the proud sponsor of one of her washout plugs – though they won’t let you take it home apparently.

People may have exactly the information that you need, and are usually very pleased to be asked. Some of the photos I’ve used have been very happily offered for our entertainment and education – or there’s always your imagination or a similar locomotive type to take a good guess from. I use photographs particularly when detailing models, often estimating the dimensions by eye. A lot of the photos I took of the J15 are provided in the book for this purpose.

The J15 boiler undergoing repair, showing the smokebox saddle underneath.KEITH ASHFORD

DRAWINGS

There may be numerous sources of drawings to help you in your build, or you might want to draw your own. Many modellers start with General Arrangement (GA) drawings: these are drawings of the full size loco, and show every detail that enabled engineers to build the real thing. They are works of art in themselves. If you want to know the shape of something you can’t see, a GA will almost certainly show it, from above, below and either side, and as such their main disadvantage is that they tend to be very complex and can be difficult to read. Services such as the National Railway Museum Search Engine are making GAs much more easily available.

It can be very helpful to prepare your own sketches from a GA as you will get to know the loco better and gain a feel for how it is put together. I’ve included my drawings where I used them as an aid to construction: I apologise now for any inaccuracies, and have simplified some of the measurements to ease construction.

I would recommend that you try to get hold of at least one drawing from the following sources. Detailed outline drawings may be obtained from Skinley Drawings, and in the case of LNER locos such as the J15, Isinglass produce an excellent range featuring a great deal of useful prototype information from a variety of viewpoints. There are also some beautiful drawings available from the website of the Great Eastern Society, or you can download some nice ones from the Connoisseur Models website, who incidentally produce a lovely J15 kit in 7mm scale. In fact you’re spoiled for choice with the J15.

If you are lucky in your googling you can obtain some very good drawings from the internet, which can be printed out and resized by photocopier. And of course there are a great many illustrations available in magazines and books and from specialist historical societies.

Do try and stick to one drawing as there may be slight differences between them, and always check against the prototype measurements in case there are any inaccuracies due to scaling up or down, or the paper stretching. I also compare drawings against my photos for any oddities, and if the photo is different I amend the drawing.

In short, find or prepare a drawing that works for you, make sure it’s accurate enough to be useful to you, and stick to it.

An example of a General Arrangement drawing.

PREPARING TO BUILD

WORKING ON THE RAILWAY

Knowing how the real thing works can be indispensable when building a model. It allows you to understand why some of the bits and pieces are where they are, and hopefully to notice if you’ve left something off.