Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

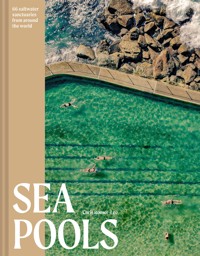

WINNER in the Architectural Book Awards 2024. SHORTLISTED in the British Book Design and Production Awards 2024. A celebration of sea swimming – looking at the architecture, history and social significance of sea pools around the world. The sea can be challenging and changeable. Protected from the dangers of currents, crashing waves and extreme cold, sea pools (also known as tidal or ocean pools) are manmade pools that provide a safe space for swimmers to enjoy the benefits of the sea at all states of the tide and weather. Sea Pools begins with an introduction to sea pools within the history of outdoor swimming, their unique designs and architectural significance and commentary on the resurgent appreciation for sea swimming in the 21st century. Chris Romer-Lee selects 66 of the most beautiful and culturally significant sea pools from around the world, including the 25-metre cliffside Avalon Rock Pool in new South Wales, Australia, the sublime Pozo de las Calcosas in Spain that is shrouded in volcanic rock, and Ireland's historic Vico Baths to name but a few. Sea Pools also includes four insightful essays: Nicola Larkin looks to the next generation of ocean pools in her exploration of how we can conserve, protect and regenerate the coastline; Therese Spruhan testifies to the healing and transformative benefits of ocean swimming; Freya Bromley discusses her odyssey to swim in every sea pool in Britain; and Kevin Fellingham reflects on the importance of sea pools in South Africa. The book is illustrated throughout with beautiful colour photography, as well as fascinating archive material to give an insight into the provenance of these vital sanctuaries.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 156

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

CONTENTS

Introduction

Europe

United Kingdom

The Tidal Year

Africa

Tide and Time

Australia

Next Generation Ocean Pools

Saltwater Sanctuaries

Rest of the World

Further Reading

Picture Credit

Acknowledgement

Index

Introduction

The ocean exerts an inexorable pull over sea people wherever they are – in a bright-lit, inland city or the dead centre of a desert – and when they feel the tug there is no choice but somehow to reach it and stand at its immense, earth-dissolving edge, straightaway calmed.

Anuradha Roy, The Folded Earth

Whether it’s the walk along the promenade to find the staircase that drops over the chalk cliffs of Walpole Bay, the drive down the track to Tarlair Outdoor Pool (see here) or the walk across the granite rock shelves of Cornwall, tidal pools are etched into the UK’s coastal towns. Big or small, thriving or dormant, there’s something about these structures that is both mesmerizing and overlooked. Everyone knows what they are but have seldom stopped to think about why. Why they’re there or what it took to get them there. Whether they are hewn from rock or cast onto a natural rock shelf these pools always solve a problem: providing safe access to water.

Access to water was a theme that emerged in my architecture practice, Studio Octopi, in June 2013. While on a family holiday to Zurich, I was encouraged to enter an open-call competition for ideas to develop the banks of the River Thames in central London. At the moment I received the details I was admiring Zürichsee Kreisel, one of many swimming facilities built along the banks of Lake Zurich and the River Limmat. ‘Cradled in nature’ was a phrase that came to me, one I used to describe proposals for a floating lido on the Thames (see here), and one I often revisited in my research for this book. Ideas were bouncing around my head as I returned to London. How exactly do you achieve a swimmable and accessible River Thames, and why would you want to?

As to the ‘why?’, over the last decade there has been a resurgence of outdoor swimming across the country and the world. Indeed, most of this book was plotted swimming lengths of the Serpentine in Hyde Park and pondering the significance of having safe access to water to swim in. Lakes, rivers and other wild resources are a welcome antidote to the unnatural indoor environments that leisure centres offer.

The restoration of historic outdoor pools has been a focus of the practice’s work since 2013. The former seawater pool, Grange Lido, then Tarlair in Aberdeenshire and most recently Saltcoats Bathing Pond. Working with the energized community groups who instigated each of these projects, it dawned on me that this type of pool was no longer being overlooked. The unfettered joy to be found in entering sheltered tidal waters cradled by a concrete or rock enclosure, protected from the turbulent sea beyond the walls and yet still being nourished by rich saltwater and marine life.

This book, however, concentrates on the coast and specifically on community-serving tidal pools. By definition a tidal pool is a seawater pool that is naturally refreshed twice a day by the high tide. Most of the pools featured in this book fall into this category. However, there are those where the seawall was built too high, breached only by swells at high tide, and so a pump was required. Exceptions to the criteria have been made on the grounds of excellence, significance and irresistibility. Regardless, tidal pools should have minimal intrusion into the intertidal, and so wholly pumped seawater pools have been excluded.

Sea bathing became increasingly popular in the UK from the middle of the eighteenth century. Encouraged by prominent physicians such as Dr Richard Russell, who recommended immersion in – and consumption of! – the nutrient-rich seawater, the health benefits of the seas took hold in public imagination. The transition from inland spa establishments such as Bath, built in the belief that natural waters could treat skin disorders and other medical conditions, to the rugged coastline had begun. British seaside towns such as Scarborough and Brighton boomed, predominantly from the wealthy aristocracy looking to indulge in seawater therapy. However, travel outside of the established cities was an arduous task and it wasn’t until the rapid expansion of the railway in the nineteenth century that seaside towns across Britain became accessible to everyone.

Beaches for sea bathing were selected only if they met certain criteria, much the same way that you might choose a beach to visit: away from a river mouth to ensure adequate salinity; stable beach surface to enable Bath chairs or bathing machines to cross it; and ample surrounding cliffs or dunes for the prescribed exercise after bathing. Bathing itself was heavily regulated by Victorian morality, with genders split between different times of day, beaches, or even whole resorts. Once suitable beaches were identified a frenzy of building work began, transforming modest seaside towns into bustling tourist destinations. The phenomenon was quick to catch on, with pools soon popping up on emerging coastal resorts across Europe.

In Australia, the perilous natural conditions of craggy shorelines and an abundance of sharks have spawned over a hundred ocean or tidal pools. James Cook and First Fleet diarists record that Aboriginals in the Sydney Harbour region made use of the harbour for food gathering and recreation. The relaxed habits of the Aboriginals around water, particularly the nakedness, unnerved the colonial administration and various edicts attempted to control activities along the beach. The arrival of colonials pushed Aboriginal communities inland and their fish traps were adapted for colonial recreation. There are records of naturally formed rock pools being used widely by the early settlers. Plugging gaps in the rockpools was commonplace and often led to the gradual expansion of the bathing spots. An 1839 diary entry by Lady Jane Franklin (second wife of the English explorer Sir John Franklin) recorded that ladies were using a women’s pool, Nun’s Rock Pool in Wollongong, and that the military had erected a hut alongside the pool to maintain their privacy. In 1876, McIver’s Ladies Baths was built as the first formalized pool on a rock shelf, providing safe access to the ocean with a naturally replenishing supply of seawater.

The Australian beach was always seen as the great leveller, an icon of an implied classless society: unrestricted, unsupervised, accessible by all. Within this public domain are ocean pools that go to characterize so much of the coastline, particularly the east coast. The use of ocean pools by Australia’s migrant communities is encouraging and they remain well used among all the communities along the coast. McIver’s Baths has seen off challenges to its important role in the community and become a haven for pregnant women, as well as those in the Muslim and LGBTQI+ community, bringing people together in a safe, social space.

Much like Australia, in South Africa the need for safe bathing conditions in treacherous coastal landscapes has led to the development of around 90 tidal pools. Most of South Africa’s enchanting pools pop up in densely populated areas along its 3,000km coastline, but many too are the product of a history of racial segregation. Under the apartheid regime, 3.5 million non-white citizens were forcibly displaced and relocated in areas categorized by skin colour. In 1950s Cape Town, an inhospitable desert area known as Cape Flats was used for rehousing people of colour from the areas designated ‘whites only’ under the Group Areas Act. The enforced segregation meant that large swathes of the coastline became a patchwork of zoned beaches for designated racial groups. This resulted in huge disparities in the allocation of beaches, with non-whites being relegated to smaller, less accessible and often dangerous beaches. To provide safe recreation along the perilous coastline, several large resorts were planned and constructed in the mid-1980s. The grand Strandfontein and Monwabisi Resorts incorporated two of the largest tidal pools in the southern hemisphere. The designs were ambitious and flamboyant, referencing both the seaside towns of 1900s northern Europe and the cultures of southern Africa.

However, completion of many pools and resorts coincided with the collapse of apartheid, and beach fronts increasingly became sites of peaceful struggle and resistance. Multiracial protest swims, ‘bathe-ins’, and picnics on the remaining whites-only beaches persisted, with a major role played by the Mass Democratic Movement that used slogans such as ‘Drown Beach Apartheid’ and ‘All of God’s beaches for all of God’s people’. By 1986 Cape Town had opened its beaches to all without waiting for government authority and by 1989 President F.W. de Klerk requested that local authorities desegregate all remaining beaches reserved for specific race groups. These mega tidal pools and their pavilions have a fraught history of racist wrongdoing, yet the resulting pools have remained embedded in the coastal landscape, offering refuge to all communities.

Tidal pools may provide respite from political unrest, but poor water quality knows no boundaries. From Kent to New South Wales, polluted water ravages beaches. Despite outdoor swimming undergoing stratospheric popularity, persistent coastal pollution is worse than ever, an undeniable by-product of climate change. In England, for instance, water companies continue to avoid accountability for dumping polluted floodwaters into the sea, closing off swimming areas and tidal pools. Globally, the bombardment of coastlines with council regulatory signage highlights how governments are attempting to wash their hands of increasingly polluted natural waterways. Despite pollution issues continuing to hamper outdoor swimming, there is now an even more resolute determination to embrace the outdoors, with the health and wellbeing benefits of ‘blue’ spaces widely accepted.

Beyond this, tidal pools are important pieces of social infrastructure. They are liquid piazzas, village greens, town halls and all the other places we meet and socialize. Far from being left to the elements, tidal pools are being bolstered by communities united through a common cause to restore, protect and manage their facilities. Now is the time to build more of these pools, both to encourage growth in tourism but also to ensure that access to water is there for all. In her essay, Nicole Larkin reveals how her analysis of ocean pools in New South Wales has informed the design for Australia’s first new tidal pool in over 50 years. Returning to the roots of creating a place for everyone to swim, Nicole has designed a model for all future pools, one that is accessible to a diverse range of users. Studio Octopi, in collaboration with marine ecologists Dr Ian Hendy and Ian Boyd, have developed a tidal pool concept that combines habitat creation with leisure use. The pool is proposed for heavily urbanized beaches, with existing coastal development and no designated environmental protections and would build on work done to recognize and boost marine habitats in and around tidal pools, putting back what coastal developments have taken away and significantly enhancing the habitat complexity. Using artificial rockpools within and alongside the main pool, marine life will return to the beach along with residents, providing a lifeline to many seaside resorts.

And back in London, our central concept remains providing safe access to the river, for everyone. The Thames has a long, often eccentric, history of swimming. In Caitlin Davies’s Downstream, A History and Celebration of Swimming the River Thames, she records the rise, fall and rebirth of Thames swimming over the years, from competitive swimming in the river itself to leisurely floating pools. The last floating bath opened at Charing Cross in 1875. It was a 41 x 7.6m barge covered by a beautiful cast-iron and glass enclosure. The river water was filtered and heated before being pumped into the central pool. Studio Octopi’s proposals were widely published because of the direct link between the ongoing works to clean up the Thames and efforts to reconnect Londoners with the lifeblood of the city. Utilizing a newly cleaned waterway for swimming has already been realized in Copenhagen Harbour – surely London could make the same strides and open a natural river-based pool? The practice remains optimistic that the link will be made by the authorities and Londoners will get access to London’s largest public space.

From gender-segregated sea bathing in the nineteenth century to racially segregated swimming in the twentieth century, tidal pools are rooted in our coastal histories, often as the silent bystander to a dark past, but always there to serve a community and provide safe access to water. The breadth of users has expanded since the Victorians flocked to the coast and the inclusivity is stronger than ever. These liminal places bridge the space between a chlorinated pool and the open ocean, providing a dose of the wild in an enclave of safety. This book explores some of the most astounding tidal pools that can be found around the world and is a springboard to whet the appetite of those interested in exploring these natural wonders further.

BELMULLET TIDAL POOL

Location Belmullet, Co. Mayo, Ireland

Built 1984

Designer/Engineer Club committee and Paddy McManamon (engineer)

Size 20 x 10 x 1–2m (large pool), plus toddler pool

Community Group Belmullet Swimming Club

Belmullet Tidal Pool looks like a 1970s utopian vision that should have stayed on the architect’s drawing board. Thank God it didn’t. This large cuboid mass, with the simplest of details, has been cast onto the beach. It is a rectilinear tour de force, more akin to an art installation than a pool and thoroughly engrossing to look at. However, according to Brendan Mac Evilly (author of At Swim), ‘through time and familiarity the pool is no longer strange and unusual to local swimmers’.

If it hadn’t been for a handful of strident female swimmers defying the male-only beach in the 1960s, none of this would have happened. They entered the water off the slipway, heading for a rock about 30m from the beach. The popularity of the swimming area quickly increased but, despite calls for a local indoor pool, the council never succumbed. However, Ann Maguire had other ideas. After spotting a tidal pool on a trip to Sweden, she partnered with the committee and a local engineer and drew up plans for Mayo’s very own tidal pool. In 1984 the pool opened to huge success. The pool needs to be emptied and cleaned to prevent surfaces from becoming too slippery. This has become an important fixture in the town calendar because as the rising tide overtops the walls it creates a spectacular sight, similar to filling a giant bathtub.

I can’t see this mass of concrete ever being consumed by the North Atlantic rollers.

CALHETA DOS BISCOITOS

Location São Jorge, Azores, Portugal

Built 1969

Over hundreds of thousands of years volcanos have spewed lava to form these sublime emerald isles 1,500km from the Portuguese coastline. The coast of São Jorge is fractured by deep breaches and coves, often creating beautiful natural swimming pools where the lava flow has come into contact with seawater to create curious geological formations. These ancient volcanic eruptions also formed the fertile fields where the vineyards grow Verdelho wine.

Biscoito (meaning cookie in Portuguese) is the name given to recent volcanic breccia terrain and lava fields throughout the Azorean archipelago. Calheta is the largest of the volcanic pools punctuating the coastline. These spectacular deep pools of clear water cradled by basalt volcanic rock were adapted for human pleasure in 1969. The new infrastructure, concrete walkways and bridges now allow safe passage between the pools. They were the first natural pools on the island to undergo these changes. Several bathing places have since been established along the coast to the delight of locals and visitors.

CALOURA

Location São Miguel, Azores, Portugal

Built 1962

In August 2019 two enormous waves swept into Porto da Caloura, engulfing one of the most enigmatic tidal pools in the northern hemisphere in a matter of minutes.

Despite the pool being red-flagged due to the tidal surge, locals and holidaymakers were at the end of the breakwater, enjoying the mesmerizing threshold of ocean and pool when the waves hit. Remarkably there were some minor injuries but nothing serious. The pool, encased in volcanic rock and concrete, survived.

In 1962, Manuel Egídio de Medeiros, councillor of the Municipality of Lagoa, together with a group of residents of Caloura, raised the money for a collaborative project with the municipality to build a public swimming pool at the end of the Caloura breakwater. The breakwater had been built to transport cereals and wine from Vila de Água de Pau to the capital city of Ponta Delgada.

There was already a shallow natural pool with some concrete steps, so forming the pool within the cavity was relativity simple. However, the concrete plateau needed to be raised by 60cm so that it was closer to the high-tide mark, providing a deeper pool and greater sunbathing area. The stairs were extended to the new height, iron handrails were added, and an acacia diving board was fixed to the breakwater. After 30 years of serving the community, the pool was refurbished by Roberto Medeiros, son of councillor Manuel, and engineer Luís Alberto Martins Mota, Mayor of Lagoa. Despite nature’s desire to take back these pools, the community remains resilient from generation to generation.

EMERALD GATE POOL

Location Dinard, France

Built 1928

Designer/Engineer Franck Bailly (entrepreneur); René Aillerie (architect)

Brittany has some of the largest tidal ranges in Europe, making it perfect tidal-pool territory. Typically, tidal pools are built on the beach or hewn out of rocks, but not the Emerald Gate Pool. Nestled into a former natural cove on the side of the beach, this gem has a commanding view over the sands below. The castellated promenade’s serpentine form hugs the back of the pool, providing a fabulous vantage point for gazing into this oasis. Sweeping granite staircases lead from the promenade to the pool terrace, where the southerly aspect creates the perfect sheltered context. Aligned with the sweeping stairs, the remnants of a far grander diving platform remain. It offers a moment of exposition in this most sedate and tranquil of towns.

Realizing this pool took the determination of entrepreneur Franck Bailly and local architect René Aillerie. The council commissioned costs and a specification with the simple brief that the pool ‘will allow sea bathing at any time and the organization of water sports events’. In 1927, despite not being complete, the pool opened to the public and instantly had the desired effect of extending the swimming hours. A 10-m diving board was added in the 1930s but removed in the 1960s. At high tide all that is visible is the balustrade to the diving platform, while a ghostly impression of the pool’s apron can be seen below the water.