Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Espionage

- Sprache: Englisch

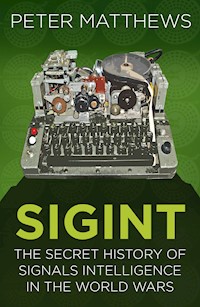

'SIGINT is a fascinating account of what Allied investigators learned postwar about the Nazi equivalent of Bletchley Park. Turns out, 60,000 crptographers, analysts and linguists achieved considerable success in solving intercepted traffic, and even broke the Swiss Enigma! Based on recently declassifed NSA document, this is a great contribution to the literature.' - The St Ermin's Hotel Intelligence Book of the Year Award 2014 Signals Intelligence, or SIGINT, is the interception and evaluation of coded enemy messages. From Enigma to Ultra, Purple to Lorenz, Room 40 to Bletchley, SIGINT has been instrumental in both victory and defeat during the First and Second World War. In the First World War, a vast network of signals rapidly expanded across the globe, spawning a new breed of spies and intelligence operatives to code, de-code and analyse thousands of messages. As a result, signallers and cryptographers in the Admiralty's famous Room 40 paved the way for the code breakers of Bletchley Park in the Second World War. In the ensuing war years the world battled against a web of signals intelligence that gave birth to Enigma and Ultra, and saw agents from Britain, France, Germany, Russia, America and Japan race to outwit each other through infinitely complex codes. For the first time, Peter Matthews reveals the secret history of global signals intelligence during the world wars through original interviews with German interceptors, British code breakers, and US and Russian cryptographers.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 539

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To my grandchildren, Hannah, Alex, Piers,Elliot, Natasha and one yet unborn.

Acknowledgements

I am pleased to acknowledge the advice and help of all those mentioned below and thank them for helping iron out some of the wrinkles in the book:

• James Gates, who helped with validating some coding exercises and assisting with the mysteries of computing when several chapters of my book disappeared from my computer’s memory.

• Joseph Mankowitz, who encouraged me with snippets of military history and participated in an exciting visit to Chicksands Priory which was a Listening Station for the Royal Air Force during the war. It is still in operation as a British Army Intelligence Corps unit.

• Paul Croxson, who was my rock in writing the book and put me right on much in the intelligence world with kind comment and guidance. He served in the Intelligence Corps in GCHQ and Germany as a traffic analyst. He is now a voluntary archivist in the Intelligence Corps Museum at Chicksands Priory and researching the history of SIGINT.

• Marylyn Blackwell provided information about the Tirpitz from the archives of Lieutenant Norman Gryspeert RN.

• The British Library staff and, particularly, Cathy Collins who guided me towards the accounts of the wartime actions in the four-page skimpy newspapers of the time in the new National Press Archive.

• Clive Matthews, who instructed me in the use of social media and helped me carry out an interview on the CNN Network in the USA about this book.

• The Public R ecords Office (National Archives, Kew) where many obliging staff guided me towards the captured logs of U-boats and British warships fighting the war at sea in both wars. The log of my grandfather’s ship HMS Venus in operation from Queenstown in Southern Ireland was of particular interest to me.

• Various members of the Imperial War Museum in London, but in particular Nick Vanderpeet and his staff at its Formal Learning Department. The exhibits in the Secret War section of agents operating gave the ‘feel’ of the equipment they used.

• The German Bundesarchiv in Koblenz have guided me through the early history of the German Federal Intelligence Agency (Bundesnachrichtendienst or BND for short) where Dr Hechelhammer has helped with information about the spymaster General Gehlen.

• Randy Rezabek in Los Angeles, who maintains an encylopedic archive on the subject of TICOM (Target Intelligence Committee) and provided documentation on German intelligence matters, some of which are quoted in this book.

• Werner Sunkel, a volunteer curator at the Wehrtechnik Museum in Nurnberg, whose father was Oberwachtmeister (Sergeant Major) at Lauf and left photos, some of which are reproduced here.

• Dr Steven Weiss, with whom I had discussions about Operation Anvil, in which he was involved as a soldier, and his experiences with the French Resistance, and he kindly shared his photographs with me for this book.

• Members of the Tunbridge Wells Library who surprised me by seeking out many books for my research.

• The German Wehrmacht veterans of the Abwehr (German military intelligence), most of whose names I have forgotten, whom I knew and talked with in Berlin as the Second World War ended and the Cold War began. Their wartime experiences, often recounted at great length during the long days and dark nights of the Berlin Airlift, are used in this book.

• Wilhelm H. Flicke (now deceased) who I got to know well was one of those mentioned above who gave me his papers that have formed a part of this book. I have had his badly typed memoirs deposited in the rare books section of the research library of the Imperial War Museum.

• Last and most appreciated is my wife Carole, who supported me uncomplainingly during the hours that I spent at the computer and even read and corrected the manuscript of this book.

Contents

Title

Dedication

Acknowledgements

Preface

Introduction to Signals Intelligence

The SIGINT Battlefield

The Value of SIGINT

1 From Cables to Codes

Cable Wars

Wireless Telegraphy Pioneers

The History of Codes

Codes and Codewords

Interceptions and Encryption

Decryption

Frequency Analysis

2 Intelligent Warfare

Intelligence in Signals

Politicians and Intelligence

3 The Pre-War Intelligence Scene

German Intelligence

Germany’s Allies

Allied Intelligence

4 Europe’s War

The Reasons for War

The Battle of Tannenberg

SIGINT in Galicia

The Miracle of the Marne

The Race to the Sea

In the Trenches

The Direction Finding Service

The French Goniometric Service

Romania and Russia

5 The War at Sea

Room 40 at the Admiralty

Codes in the War at Sea

Directionals at Sea

U-boats and Convoys

Surface Raiders

The North Sea

Jutland

6 The War in the Air

Zeppelins and Gothas

Air Battles in France

7 The War’s End and SIGINT

America Drifts into War

The Lusitania

Zimmermann and America

1918 and the End Game

The Yanks are Coming

Brest-Litovsk

Compiègne and the Armistice

8 The Inter-war Years

Minor Wars

Polish Con-Men

TICOM Analysis

The Players

German Intelligence

Cipher Machines

Non-Belligerents

9 The Second World War – The Beginning

Czechoslovakia and Poland

The Phoney War

Norway

The Battle for France and Dunkirk

Britain’s Air War

The Battle of the Atlantic

Raiding Europe

Germany’s Surface Fleet

The Balkans

The Middle East

The Desert Campaign

The Afrika Korps

The Torch Landings

10 The Second World War – The Middle

Russia

Russian Battlefield Intelligence

Japan

Sicily and Italy

Counter Intelligence

Scandinavian Resistance

France

Belgium

Holland and the North Pole

11 The Second World War – The End

D-Day

The Battle for France and the Bulge

Middle Europe – Poland and Czechoslovakia

The Bomb Plot

The War’s End

Beginning Again

In Conclusion

Appendix

Bibliography

Maps

Plates

Copyright

Preface

As war ended in 1945, some of the German Wehrmacht’s most experienced signals intelligence operators began working for Anglo-American intelligence against the Russians. As a young soldier I mixed with them, perfecting my German as I talked with them at length and listened to their experiences. I was tolerated because I brought cigarettes, which were in very short supply in Germany at that time. They believed themselves to be the elite in signals intelligence at that time – and, from their tales related to me in 1947, so did I. The triumphs and few tragedies they related at that time sounded good, but they knew little of the reverses that the Wehrmacht suffered in the signals intelligence war. So we all believed their tales of outwitting the enemy. It was not until almost thirty years later that the story of Bletchley Park began to emerge and I can imagine the astonishment they felt as the secrets began to be revealed. Most of the German signals intelligence warriors that I had met with and listened to with rapped attention in 1947 would have been dead by the time that we all knew of the story of Ultra intelligence. They have left me impressed with their achievements, even though their work had been eclipsed by Bletchley Park. They even gave me some of their private papers (bought from them for a few cigarettes which they probably used in trading on the black market).

I have been re-reading their accounts of the 1940s and have tried to set them into the considerable body of literature that has been published about British cryptography and smiled at the naivety of those German cryptographers. I decided to write this book to try and compare the abilities and shortcomings of the signals intelligence agencies of the belligerents in the two great wars of the twentieth century.

The book traces the emergence and maturity of electronic signals interception and decryption in the first half of the twentieth century, and its effect on the warring nations of the world. The place of signals intelligence, or SIGINT, in military history is not just about Bletchley Park and Enigma, but the way that the intercept services of armies, navies and air forces competed to gain advantage in battle. Intercept services of Germany’s Abwehr, France’s Deuxième Bureau and the British Admiralty Room 40 all vied with each other in their different fields from the inception of signals intelligence before the First World War. The first steps in electronic warfare had been laid and preparations were made during the inter-war years for the signals intelligence battle in the Second World War. This is its tumultuous story.

The author’s interest in wireless telegraphy, or W/T as the Royal Navy called it, began in his home town of Portsmouth where as schoolboys we were obsessed with naval matters. We all learned the Morse code at an early age and understood the concept of its communication at great distances, which is more than some of our elders managed to do.

My generation received the call to arms just as the war had ended and the fighting ceased, but as we joined the army we were to get a master class in signals warfare. We were ordered to act as garrison in Berlin and flew there in an old Dakota aircraft, which was the first flight of an operation that came to be known as the Berlin Airlift. The Russians were laying siege to the city and all food, fuel and other supplies had to be flown in by a great armada of planes to supply over 2 million people. The Berlin Airlift was a gesture of defiance to Russian demands and marked the beginning of the Cold War.

Berlin was in ruins and the most despondent place I had ever been in my life. We mixed with the Russians and even shared quarters with Red Army soldiers during our duties in Spandau Prison, where we provided the guard for Hess, Raeder, Speer and a few other Nazi war criminals. Berlin was steeped in the espionage business; the city contained one of the most forward radio listening stations that the West had in the signals intelligence war that was developing with the Soviet Union. Listening posts scanned the electronic chatter of the Red Army, and the Allies often used ex-Wehrmacht radio veterans who had served in the German intercept service during the war. Their experience was being used and analysed by the Allies through TICOM (the Target Intelligence Committee project formed to collect information about German intelligence activities during the Second World War and seize materials) and the emerging Gehlen Organisation to try and read Russian signal traffic. My German friends and I often conversed during the cold nights over a mug of cocoa, listening to their reminiscences, some of which appear in this book. From our discussions I realised to what extent interception, decryption and deception was possible in signals operations and how that intelligence could be used by the enemy. The game of electronic hide and seek in the ether, and the way it could be played, fascinated me.

Later in civilian life it seemed to me that the country was obsessed with spies in the 1950s; Burgess, Maclean, Philby in the Foreign Office, and Blunt in the Queen’s Household, were all found spying for Russia. I had seen enough of that scene in Berlin where every fourth person seemed to be a spy working in the pay of the Russians, the Americans or both. In spite of this, I began work in information research, concerning myself with how Britain handled the surveillance of German newspapers, magazines and other publications during the war. Before the war, publications were easily obtained, but with the outbreak of hostilities the supply dried up dramatically. Newspapers and other publications could only be smuggled out one or two copies at a time. The intelligence community demanded their copy to read as the contents often contained clues as to the state of the enemy’s mind and resources. Microfilmed copies were circulated to a distribution list, compiled of various Ministries in Whitehall, and Army and Navy intelligence officers needing to read the enemy’s newspapers. One of those on the list was Bletchley Park, but that did not mean anything to us then. Clues such as announcements about rationing regulations indicating the condition of food supplies in a region or an announcement of a German officer’s marriage that might identify his regiment could be gleaned from their local or national newspapers. To satisfy the increasing demand for the newspapers, magazines and even scientific papers of German and occupied countries that had been ‘obtained’, the originals were distributed by despatch riders, then delivered to many obscure addresses all over the country.

Later on, our tenuous connection with Bletchley Park earned us a tour conducted in person by its director and ex-secret service man, the late Anthony Sale. Tea and biscuits were followed by a discussion about the intelligence scene. To our surprise, Sale told us there was relatively little in the archives about how enemy intercept services operated during the war, in spite of the TICOM investigation. I searched out the papers stored away, particularly those given to me by Wilhelm Flicke, a German cryptographer, relating some of his experiences over twenty-five years of cryptography in the service of his country. His experience started in 1917 and spanned the inter-war years and, finally, in the German signals intelligence service throughout the Second World War and even beyond. Contributions from Colonel Randeweg, who had commanded German intercept units on the Western Front, as well as from other signals operatives, have shaped this book.

The reader must remember that original papers and reminiscences of German signals operatives from the time are not informed by the knowledge we have now of the intelligence activities that were operating all over the world, and that, at the time, none of us knew of the existence of Bletchley Park. German Abwehr intelligence thought that they had performed better than they did because they did not know what the opposition was doing, so some of the views that are quoted may seem a bit quaint to an informed reader. That does not disguise the fact that the Abwehr did enjoy some successes in the signals intelligence war in which they were engaged. This book is a history of SIGINT operations largely from the Axis partners’ point of view and how the intercept services perceived themselves. Its aim is to tell the other side of the Bletchley Park story.

Peter Matthews, 2013

Introduction to Signals Intelligence

The SIGINT Battlefield

This is not only the story of Bletchley Park and Ultra intelligence, and its incredibly clever and dedicated team which helped to win the war for the Allies. Less is known about Bletchley Park’s opponents in signals intelligence and what contributions they made to the war effort of their forces in comparison to the Allies. The German Enigma and Lorenz, the Italian Hagelin and the Japanese Purple coding machines were all penetrated by Bletchley Park. The German Abwehr intelligence machine in particular made progress of its own into Allied codes and ciphers; the Wehrmacht (German armed forces) believed they were winning the signals intelligence war and so they were in the early stages of the war. The complex struggle for advantage in a battle of wits between intelligence agencies and the way it was resolved is a tragedy followed by a triumph for German intelligence. Its legacy still lives on in the world’s intelligence community today, but its story began at the start of the last century.

A signals intelligence war is a most curious conflict; its participants very rarely meet and they will never know who has won the battle until years later, if ever. For instance, Colonel Walter Nicolai, head of the German intelligence agency during the First World War (1914–1916), believed that his agency dominated the intelligence scene in that war. Nicolai had a fearsome reputation as a spy master and had enormous faith in his own ability. What he did not know, however, was the extraordinary success that the British had in breaking the codes in the wireless messages his department sent, and how the British became the real victors in the war’s signals intelligence struggle. A clearer picture only emerged in 1982 when Patrick Beesly published his book entitled Room 40: British Naval Intelligence 1914–18, spelling out the achievements of the British code breakers. Nicolai never knew the truth as he died in a Soviet prison just after the Second World War. Similarly, in the Second World War, when officers of the German Abwehr signals intelligence agency boasted of their efficiency and achievements in their memoirs, they knew nothing of their opponent’s centre of excellence, Bletchley Park. The first book about Ultra intelligence derived from decoding the Enigma and other machines was published in 1976, many years after the war. Some of the German intelligence reports in the Deutsches Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archive) are amusingly naive in believing that they are the keepers of the military knowledge when Bletchley Park was looking over their shoulder and reading their messages all the time.

However, we should start at the beginning. Signals intelligence, or SIGINT as it was abbreviated by the Allies in the Second World War, is primarily an aspect of military intelligence gathering based on the interception and decoding of an enemy’s wireless transmissions. SIGINT has played an important part in warfare for just over a hundred turbulent and bloody years, and proved a powerful weapon in the hands of many commanders in the field and admirals at sea. Intelligence of this kind has developed an array of scientific techniques for eavesdropping on opponents, which are now used by most of the world’s armies, navies and air forces. It was developed during the huge conflicts that were fought in the first part of the last century when wireless messages became central to the mechanisation and mass movements of formations on the battlefield, as well as commerce raiders and submarines at sea. Intercepted signals come straight from the mouth of the enemy and could sometimes give an immediate indication of the strength, order of battle and possibly even objectives, both tactical and strategic, of an opponent in the field. Signals intelligence has proved to be a very cost-effective method of building a picture of the enemy’s strength and intentions, compared with other aspects of intelligence, although other information sources cannot be neglected in the building of an intelligence evaluation.

Throughout history military messages have had the complication of being coded, but the interception and deciphering of wireless transmitted coded signals has been one of the intellectual adventure stories of modern military and even political history. The complexity of codes and ciphers are only outlined here, although some of the principles are discussed; however, it is the effects that SIGINT has had on the conduct of military, naval and air actions which are the subject of this book. Intelligence has been a significant weapon in both of the world wars and Britain’s part as played out in the Admiralty’s Room 40 during the First World War and particularly Bletchley Park in the Second World War are well documented. People may be forgiven for thinking that these were the only signals intelligence operations of any importance during the two great conflicts, but this book endeavours to show aspects of the enemy’s signals intelligence offensive during those times. SIGINT achievements of the various combatants have ebbed and flowed over the years and their success, or lack of it, in the development of military intelligence has been largely dependent on their understanding of the concept. The function and application of intelligence by its commanders and their masters, and their ability to deploy this unique weapon of war, has not always been shown to the best advantage. A successful signals intelligence service needs to have a champion, or at least a tacit acceptance of its value in shaping battles at the highest political level. The attitude of the leaders at the highest political level to an intelligence function and, particularly, the value of the immediacy of those intercepted signals has been essential to the effectiveness of intelligence services and the military organisations that served them.

The Value of SIGINT

SIGINT was to become an important indicator of an enemy’s, or even a neutral country’s, intention to act. The decrypting and reading of an opponent’s wireless transmissions, which might contain reports of actions or movement orders for troops or ships, could be an important part of that indicator. The deciphering of diplomatic wireless transmissions that send or receive instructions in negotiations has proved to be of great consequence. An operator transmitting his message is, by and large, confident that he is not going to be overheard or, at least, if his message is encoded then it will not be understood. To get into the mind of a potential opponent is as important to a diplomat as it can be to a soldier.

Enemy signals gathered for assessment and encryption had to find their clues where they could from the ‘raw’ interceptions their listening stations were receiving. Putting together the pieces of a signal, or more probably hundreds of signals with observations from other sources, helped to create a huge jigsaw puzzle in need of evaluation. However, an intelligence officer invariably did not have all the pieces and there was always the possibility that some pieces might belong to another puzzle. They might even have been put there maliciously by a cunning advisory to make the task of clarifying the message even more difficult. General Montgomery’s intelligence officer, Sir Edgar Williams, expressed the view that military intelligence is always out of date as there was always a time lapse due to the speed of events. He went on to say that it was better that the best half truth was received on time rather than the whole truth too late. Speed in delivery of an evaluation is, therefore, often the essence of the matter. Many Ultra decrypted messages were in the hands of the commander that could use them within three hours of them being transmitted by the Germans.

SIGINT has been deployed in many forms in every theatre of war by combatants since its inception before the beginning of the last century, albeit with various levels of success. Ultra, which was Britain’s great triumph in signals intelligence in the Second World War, is estimated by some to have shortened the war by up to two years. Other less well-documented SIGINT engagements also pose the question: ‘By how much has SIGINT lengthened our wars?’ Its successes and failures undoubtedly helped to do that in the first months of the First World War, as we shall see. Similiarly, events and actions such as the interception of British Army plans in the Western desert of North Africa could have also had the effects of prolonging the war in this theatre. In the end, however, the pluses and minuses of the many actions influenced by signals intelligence are too complicated to calculate what effect they may have had on the duration of hostilities.

Intelligence reports do not win battles, but merely enable a competent commander to deploy his forces to better effect against his enemy if he knows the strength and deployment of the opposing forces and what objectives they intend to achieve. Conversely, good intelligence can be of little help to a poor field commander who cannot take the right decisions or does not have sufficient resources to fight his battle. The Battle for Crete, where General Freyberg knew from Ultra intercepts when and where German paratroops were to land but neglected to secure the runway at Maleme Airport with a few anti-aircraft obstacles, is a case in point. Denying the Luftwaffe a landing ground for troop-carrying aircraft with reinforcements may have influenced the tide of battle on the island. Battles are won by the good and well-prepared plans enacted by an able commander who has sufficient resources to fight a particular battle. Intelligence could be a powerful influence on these plans, or the commander’s reactions in battle. As a result, signals intelligence has helped to determine the outcome of not just battles, but given shape to the conduct of campaigns and even a war.

1

From Cables to Codes

Cable Wars

Telephone and telegraph communication networks had already changed the world of commerce and diplomacy in the ten years before the war. Now the nature of war itself was changing beyond imagining, commanders in the field were enabled to control huge troop movements or direct artillery fire onto targets from remote control emplacements or even aircraft spotters. The technology enabling generals to direct operations on fronts hundreds of miles away created a form of warfare of unprecedented scale and proportions. To most of Europe’s young adult men about to be called to join the service of their country at the beginning of the last century, being able to communicate over great distances had an almost magical feel. Germany’s scientists were in the forefront of this new communications revolution and Imperial Germany’s government saw great possibilities in the telephone well before the war began. An ambitiously large network of telegraphic wires had been laid across Germany connecting important cities and, in particular, their military establishments. The High Command would be able to direct the great battles yet to come, using their newly installed telegraphic communications network, making the industrial scale of the First World War a possibility. This new technology would have far reaching effects on the war’s fast-moving opening stages.

As the First World War began, initial actions were directed against communications networks in the shape of the great undersea cables connecting the major cities of the world. Cables were far more important to international communications at that time than radio telegraphy. The earliest cables were laid in the 1850s and the first cable links between Europe and America, or rather Canada, were made at that time. Complex cable networks linked the colonies of both the British and the German empires to their capitals and homelands; these links had been laid years before to transmit market and financial information to support the international trade of the world.

On the other hand, wireless technology was still emerging, although Germany, using the Nauen wireless station near Berlin, had just made her first long-range wireless transmission in 1913 to her station in Togo, German West Africa. The transmission was barely audible and, by comparison with a cable message that would have been clear and distinct, it seemed that wireless telegraphy still had some way to go. Britain had extended her own cable networks to every important part of her empire as a priority and owned, or at least controlled, much of the world’s networks. She was also experimenting with wireless telegraphy and was slowly increasing the distance of global wireless transmissions. In 1910, communication was even made with an aeroplane in flight. Cable links, however, would initially prove more vulnerable to attack than wireless so, two years before the war started, the Committee of Imperial Defence planned a crucial action that determined the shape of the future signals intelligence war. A secret ‘war reserve’ standing order was issued by the British government to cut Germany’s international undersea cables in the event of hostilities.

Just two days after war was declared, the cable ship Telconia slipped her moorings in Harwich on 5 August 1914 to steam out to a position near Emden on the German coast to dredge up, lift and cut five German telegraphic cables. The cables that were severed ran down the English Channel to connect with France, neutral Spain, Africa and to Germany’s many friends in North and South America. A few days later, with second thoughts, the Telconia returned to dredge up and reel in many more thousands of feet of cable to ensure that the cable damage was irreparable. The Imperial German government could no longer send urgent cablegrams to their African colonies or embassies in many neutral countries around the world. One of the war’s first military actions by the British was to raid and destroy the German cable station in Lomé in West Africa, isolating German cruisers on station in South Atlantic waters. Without the cable-based telegraphic communication to their bases, they would have to use wireless transmissions and potentially give their positions away to a listening enemy. The only cable left intact was the German-American line to Liberia and Brazil, and that was cut in 1915. All urgent messages to diplomatic, naval and military stations now had to be sent by powerful radio transmission from Nauen radio station. Soon radio researchers of the British Marconi Company began to pick up an increasing number of radio signals they identified as German naval communications. They immediately brought the text of those messages to senior officers at the Admiralty, who were initially at a loss as to what to do with them.

Transmissions began to be intercepted regularly by hastily erected listening posts on the east coast of England in the first days of the war. Listening, or ‘Y’, stations soon built up into a wide network of establishments dotted up and down the length of the English, Scottish and, later, Irish coasts. Intercepting German transmissions grew into a major surveillance system and the British also set up ‘Y’ stations down in the Mediterranean later in the war. The crew of the Telconia, and probably the British government, would not have realised that they had begun the work of Britain’s code breakers.

Attacks on communications were not just limited to the British as German troops also raided a number of British and French cable stations, cutting overseas connections with India, as well as attacking cable stations on the East African coast which linked Britain’s far flung empire. Baltic Sea cables were also severed by the Germans as they came to realise the importance of communications, so exchanges between Britain and her Russian allies became much more difficult.

Cutting Germany’s cable communications fundamentally changed the signals intelligence battleground, although neither the Committee of Imperial Defence nor the German High Command could have foreseen its implications. German marine and, to some extent, military communications now became increasingly dependent on wireless transmissions. They were much slower in developing a listening network, but when they had realised that their cable network had been severed they began to develop a wireless telegraphy system to replace it. Nobody had yet realised how vulnerable electronic messages were to interception and decoding, or the part that SIGINT would play in shaping the the First World War.

Wireless Telegraphy Pioneers

Research into wireless telegraphy technology developed seriously in the 1800s, but early progress was mainly centred on the scientific aspects of this new mode of communication. It wasn’t until later in the decade, after the scientific principles had been established, that it led to an increasing number of commercial products and services being created. Outstanding among the technology’s pioneers, and destined to become a principal figure in the field, was an Italian named Guglielmo Marconi, who had begun to turn workbench-based experiments and pilot projects into working devices. He improved the transmission and reception of his wireless transmission device from a few hundred yards to miles and then hundreds and, finally, thousands of miles. He provided the expertise to build, operate and service the wireless telegraphy products he developed and, just as importantly, the business drive to create a market for them. Marconi rapidly grew from a radio ‘nerd’ working in his attic on a technology that no one had heard of, into a hard-headed business man negotiating with governments and building the Marconi international brand. He became a dominant force in the wireless telegraphy industry and, although he had many competitors, great and small, none made their mark with the public quite like he did. He and others in the field promoted wireless telegraphy on land and sea, and even in the air, in the first decades of the twentieth century until, by the 1930s, it began to be part of everyday life. The story of early wireless telegraphy was largely the story of Marconi because he brought wireless telegraphy to the market for good or ill. He himself said, ‘have I done good in the world or have I added a menace?’ The following pages seem to indicate that the industry that he did so much to build has proved a mixed but essential blessing to the military.

Marconi’s interest in electro-radiation, or radio waves as they are now known, enabled him to get a place to study the emerging technology and its science at the University of Bologna in Italy. He was inspired by the research of Heinrich Hertz and others in Germany and from this he developed his own early experimental devices enabling him to design a wireless telegraphy system for sending signals a distance without wires. It consisted of a simple spark-producing transmitter, a wire as an aerial, a coherer receiver and a telegraphic key to operate the transmitter that sent the dots and dashes of Morse code, and a telegraphic register that recorded those Morse letters on a paper tape. His initial device could only receive signals over a short distance, but he proved that it worked and that the transmission and interception of Morse code was a feasible proposition.

By 1895 Marconi had lengthened the antennas of his sets, enabling him to transmit his messages for over a mile. He needed money to develop the capability of the technology, so he wrote to the Italian Post Office describing what his device could do – he was promptly invited to take himself off to a lunatic asylum. This rebuff pushed Marconi to take his wireless telegraphy device to London to seek interest and funding for his work as he spoke excellent English. He was able to demonstrate the machine to an amazed audience at the Post Office in London where a plaque on the wall of BT (British Telecoms) Centre still commemorates the first public transmission of wireless signals. This was followed by a number of demonstrations to the British government who invested in the new science. By March 1897, with the increased funding they gave him, he was able to transmit his signals for a distance of nearly 4 miles. This was followed by his first transmission across the English Channel to France in 1899. Later that same year, the American liner SS St Paul was the first ship to report her imminent arrival in Southampton using a Marconi wireless set at the Needles on the Isle of Wight while the ship was still almost 70 miles from port. Wireless telegraphy caught the interest of ship owners around the world but, in particular, the world’s navies, who saw beyond its commercial use to the way it could be used in war. The naval manoeuvres of 1899 transmitted messages from ship to ship over a distance of almost 100 miles. The Royal Navy immediately placed an order for thirty-two of Marconi’s wireless telegraphy (W/T) sets, and the Italian Navy followed suit with an order of twenty – Marconi was on his way. His next step was to span the Atlantic, so in December 1901 he set up his transmitters connected to a 500ft antennae supported by a kite in his attempt to span the ocean with his Morse code message. It consisted of the letter S in Morse transmitted as dot, dot, dot continuously, hoping that it would travel over 2,000 miles from Ireland to Newfoundland. There was some doubt at the time that the signal could be distinguished above the atmospheric noise, but when he announced his scientific advance the public believed him wholeheartedly and Marconi took his place in history.

A couple of years later, President Theodore Roosevelt was able to send greetings to King Edward VII transmitted from Marconi’s Glace Bay Radio Station in Nova Scotia, marking the first wireless message transmitted from North America. A dramatic confirmation of the benefits of the new technology came in 1912 when the Titanic famously struck an iceberg at speed in the North Atlantic and began to sink. On the stricken liner the two radio operators, Jack Phillips and Harold McBride, who were Marconi International Marine Communications Company employees, sent their distress calls that summoned the RMS Carpathia to pick up the survivors of the tragedy. Marconi’s Glace Bay Radio Station was the first to receive the Titanic’s distress call and it was another of Marconi’s men, David Sarnoff, who received and published the names of the survivors from the Carpathia via Marconi’s wireless set. Wireless telegraphy suddenly became a ‘must have’ item in vessels of the world’s navies and also most large liner and merchant ships that sailed the oceans of the globe. Marconi gave evidence concerning the use of wireless telegraphy in the Titanic disaster at the official inquiry in 1912 recommending wireless telegraphy procedures that he felt were needed during emergencies at sea. The British Postmaster General stated afterwards: ‘Those that have been saved in the disaster have been saved by one man, Mr. Marconi and his marvelous invention.’ It is sure that without the SOS wireless distress signals that the Carpathia received from the Titanic its sinking would not have been just a disaster but probably also the world’s greatest maritime mystery. The great liner would have disappeared among the ice flows of the dark North Atlantic with all on board without trace or sound.

Wireless messages could be received by anyone with the right equipment and the new means of communication was to prove a boon to mankind in many ways. The blessing extended to the military, which needed to communicate confidentially with its men on the ground using coded methods of transmission. Codes and ciphers have made it possible to maintain secrecy in messages and the military were able to send that coded form in Morse to their controllers, whether in London or Moscow. The code breakers were yet to arrive on the scene.

The History of Codes

Encryption of messages into coded form is a science and, like so many other scientific disciplines, has its roots in the culture of ancient Greece. In the Greek language kryptos means ‘secret’ and graphos means ‘writing’; thus we have the science of cryptography. There are earlier examples of codes among the ancient Egyptian, Hebrew and Asian scholars, but the main tradition of European encryption seems to have come down from the ancient Greeks and was later expanded by the Romans. Coded messages have been used, principally by military men, through the centuries. The first of them recorded their coded messages by stylus and then on papyrus, and in later centuries quill pens and parchment. Within living memory, pen nibs dipped in inkwells inscribed copperplate writing on to paper in laborious hand-written text. Now, of course, it is the universal computer that records and even solves the code using methods built on algorithmic principles devised by the ancients. The science of cryptography ‘stands on the shoulders of giants’, like so many of our other intellectual and scientific achievements, therefore a bit of cryptographic history is needed to help the reader appreciate how the ‘Black Art’ of encoding and decipherment of messages has developed and some of the ways it has affected our modern world.

In 405 BC the Greek General Lysander of Sparta was said to have received a coded message called a scytale in a servant’s belt that enabled him to surprise the Athenian Navy at Aegospotami. The encrypted message was read by winding the belt around a wooden baton which the messenger also carried with him to help the general reveal the hidden text. When Lysander was warned of the Athenian threat he immediately set sail to surprise and defeat them. Alexander the Great used codes and even devised the first postal censorship system while besieging General Memnon of Rhodes, who was fighting for the Persian King Darius at Halicarnassus in ancient Greece. Alexander wanted to know the state of his troops’ morale, so he encouraged his soldiers to write home and then intercepted the courier to read the letters to see how his men truly felt about their army’s conditions. By reading their private correspondence, he was able to identify many problems and grievances which he was able to put right, and also to identify the unreliable men in the ranks whom he sent home. Other Greek military men devised an encryption method that substituted letters for numbers using a table called the Polybius Square (below). Using the table shown as an algorithm, the key enables the reader to decode a text in which the letter A is represented as 11, B is 12 and so on. Thus enciphering the word ‘war’ using the table gives the coding of 52 11 42. A similar code to this based on the Polybius Square was still being used in the trenches of Northern France in the First World War over 2,000 years later.

In the fifth century BC Herodotus, known as the Father of History, left us an account of a bizarre method of secret writing. It was to shave the head of a slave and tattoo a message on his scalp, and then, after his hair had grown again, the poor slave was sent off through enemy lines to get a hair-cut and so deliver the message. Julius Caesar is said to have used a simple substitution code algorithm like the one described, but the key to his code was to replace the letters in his message, not by one place in the alphabet but by three places. Thus A became D, B became E and so on, so the word ‘Caesar’ would then be encoded as ‘Fdhvdu’. The decrypt would be pretty easily worked out as long as you knew your alphabet backwards. This substitution cipher is one basic form of today’s modern encryption system and, as a result, cryptologists refer to this form of coding method as the Caesar Shift Code.

After the fall of Rome, writing as an art decreased and, consequently, so did the need for secret writing and codes until about the fourteenth century when Italian banking families began using simple codes for commercial purposes. More complicated ones were being devised by diplomats in Europe to transmit confidential reports to their masters back home about the ever more political dramas in the courts of Europe. Elizabeth I’s court had a most efficient state security service headed by Sir Francis Walsingham. Not only did his service devise and use their own codes and ciphers, but they also broke other people’s codes. The queen’s spymaster had developed what was for the time an effective coding and decrypting bureau. Plots and counter-plots, mainly by Catholics who wanted to depose or assassinate Elizabeth, were being frequently discovered by Walsingham’s agents who intercepted messages and decrypted them if they were in code. An alarming plot was uncovered by Walsingham involving Mary Queen of Scots, who was a Catholic figurehead and at the centre of most of these plots. She had a cipher clerk, Gilbert Gifford, who was arrested at Rye Harbour and ‘persuaded’ to act as a double agent. He was instructed by Walsingham’s agent Thomas Morgan to spy on the Queen of Scots. Gifford was to act as an agent provocateur and encourage coded communication between the imprisoned Scottish queen and her Catholic colleagues outside her prison. Most messages were intercepted on their way to the unfortunate queen and painstakingly deciphered by Walsingham’s cryptologist, Thomas Phelippes, revealing details of a plot to murder Queen Elizabeth. This early example of code breaking saw Mary executed in 1587 and, later, led to a train of events that caused Philip of Spain to launch the Armada against England.

Daniel Defoe is best known as the author of Robinson Crusoe, but is also remembered as the father of the British Secret Service. He was a prisoner in Newgate Prison in 1704 when he wrote to the Lord Treasurer of England, Robert Harley, proposing that he should form a secret service to spy on the gentry of England. The devious Harley liked the idea and got Defoe out of jail, setting him to work to provide a network of spies and agents linked by coded messages throughout England and, particularly, Scotland. At the time the Act of Union between England and Scotland had not been ratified by the Scottish Parliament, so Defoe was asked to convince the Scottish business community that they would grow rich by trading with England if they entered the Union. He personally influenced the Scottish Parliamentary vote to enter the Union with England by pamphlets and promises when it seemed that, in general, Scottish public opinion was against it. He was a major figure in forming the Union as he influenced political opinion to accept the concept which must have enriched many people, although he died unrewarded and in poverty.

In the later years of the Napoleonic Wars, Napoleon developed his ‘Great Paris Cipher’, a complex code used to pass orders to his marshals, receive reports and direct his armies. The French cipher was cracked by Wellington’s code breaker, Major George Scovell, who collected some coded despatches captured from French couriers with the forceful help of Spanish guerrillas. Scovell spent many lonely nights in his tent by candlelight decrypting Napoleon’s orders; the intelligence he gathered from his code breaking helped Wellington to secure his many victories in Spain. The original manuscripts over which Scovell toiled into the night can still be seen in the National Archives at Kew. By 1812 most of Napoleon’s ciphers had been broken and much of their contents were read regularly by the British Secretary at War in London. Wellington, while fighting the French in Spain, valued the intelligence greatly and was quoted as saying:

Although we rarely find the truth in public reports of the French government and their officers, I believe we may venture to depend upon the truth of what is written in a cipher.

Lord Wellington, May 1813

George Scovell masterminded the major code breaking achievement of his time almost single handed; he was probably Britain’s first serious cryptanalyst, although Britain was about to produce many more. Europe’s battlefields spawned a great many secret codes and ciphers, but it was not the only theatre of war that used coded information: for example, George Washington used ciphers to communicate with his generals and spies during America’s War of Independence. However, the seismic change in the science of cryptography occurred in Europe with the coming of wireless telegraphy and its coded transmissions at the beginning of the First World War.

Codes and Codewords

In common parlance a code is thought to be a single form of secret signal or writing, but in reality codes and ciphers represent two different forms of encryption. A code assigns a specific meaning to a word, phrase, flag or light, generally calling for some kind of action. For example, a traffic light transmits a coded message to you when the red one orders your vehicle to stop. When the beacons flared from hill top to hill top in July 1588, England knew that the Armada had been sighted and it was time to assemble the troops. Nelson’s Royal Navy used a complex set of codes based on flags; every flag was illustrated in a signals flag book with a specific meaning allocated to it. Each ship’s captain had such a code book enabling him to read his Admiral’s message flying at the flagship’s masthead. This code of flag signals had only been perfected for a couple of years before Trafalgar and, if the battle had been fought just a few years earlier, Nelson would not have been able to signal to his fleet ‘England expects every man to do his duty’ using just a few flags.

The author recalls most vividly the use of secret codes during the Second World War in the BBC’s European Services broadcast every evening. Between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m., and after the news, messages to members of the resistance in Nazi-occupied Europe were sent in code. The agents were risking their lives not only by their espionage attempts, but even by just listening to the radio programme while we at home were tuned into the programme in safety. Every evening the programme started with Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony as its signature tune. It began dramatically with four single notes DUM DUM DUM DAHH sounding like the Dot Dot Dot Dash of the V for Victory sign in the Morse code. Beethoven’s Fifth became Europe’s most popular tune for people in Nazi-occupied countries who would hum or whistle it among friends but anyone found listening to BBC programmes could get a visit from the Gestapo; nevertheless thousands did tune in. V signs were daubed on walls all over Europe, so it was as universal as graffiti is nowadays, but to be found defacing a wall with a V sign at that time meant you would be taken away by the Gestapo. The author listened to the messages of hope sent from the BBC telling Europe’s people about the war’s progress; then at the end of the programme the announcer gave a series of quite meaningless messages that only certain members of the resistance could understand. ‘The harvest is good’ was one that we remember; it carried instructions to do some deed of destruction or to meet a plane carrying guns and reinforcements to France or the Low Countries. We never found the meanings of those strange codes, of course, but what we did know was that these were coded orders to anonymous men and women to do brave and dangerous deeds. One memorable exception was a code phrase about the ‘sobbing of the violins’; we were told after the war that it alerted members of the resistance that the D-Day landings would occur shortly. It was an eerie sensation to be a listener to these strange coded messages directed to resistance fighters engaged in Europe’s struggle while we sat at home in comfortable security.

A network of agents needed to keep in touch with their home base and did this by a radio transceiver. Being an operator was the most dangerous job in the resistance, as an agent had to go on air to transmit his message for all to hear and his radio waves advertised his location to the direction finders of the enemy. The radio set could probably fit into a suitcase, but it was always in danger of being checked by an inquisitive sentry or a zealous policeman. Nevertheless, the radio has to go with him or her wherever they went as the operator was always looking for a quiet place to code their message and transmit it. The codes the operators used had to be simple as they could not afford to carry around the code keys or any written material that operators in the London control office had available to them. An agent’s method of ciphering his message had to be easy to memorise using a simple and straightforward method. The Double Transformation Code was a cipher used by agents during the war and the key to it was a simple phrase. The code phrase could be as basic as THANKS FOR SOMETHING and would be known to both the agent in the field and their controller at their home base.

To encode a transformed message the letters of the alphabet would be numbered, to keep things simple we have selected 1 to 26 where A equalled 1 through to Z which is number 26. The code phrase has eighteen letters and by giving each letter its alphabetical number it looks like this.

T

H

A

N

K

S

F

O

R

S

O

M

E

T

H

I

N

G

20

8

1

14

11

19

6

15

18

19

15

13

5

20

8

9

14

7

The message to be sent is RAID ON THE TARGET IS HIGH RISK THREE AGENTS MISSING SO FAR. This would be written out so that each of its letters would be under one of the eighteen letters in the agent’s key phrase, as below.

T

H

A

N

K

S

F

O

R

S

O

M

E

T

H

I

N

G

R

A

I

D

O

N

T

A

R

G

E

T

I

S

H

I

G

H

R

I

S

K

T

H

R

E

E

A

G

E

N

T

S

M

I

S

S

I

N

G

S

O

F

A

R

20

8

1

14

11

19

6

15

18

19

15

13

5

20

8

9

14

7

The code would then be made into a string of meaningless letters by taking each column above from the one numbered 1 (i.e. under A in the key word) to the next numbered column in the sequence, in this case 5 (under E in the code word) to create a string of letters, like so:

1

5

6

7

8

8

9

11

13

14

14

15

15

18

19

20

20

ISN

IN

TRF

HS

AI

HS

IM

OTS

TE

DKG

GI

AEA

EG

RER

GA

RRS

ST

So the new code word becomes:

ISNINTRFHSAIIHSIMOTSTEDKGGIAEAEGRERGARRSST

This new ‘word’ would be then translated into a string of numbers, by giving each letter in the word its alphabetical number, using the form 1=A to Z=26 as before:

I S N I N T R F H S A I I H S I M O T S T E D K G G I A E A E G R E R G A R R S S T

9 19 14 9 14 20 18 6 8 19 1 9 9 8 19 9 13 15 20 19 20 5 4 11 7 7 9 1 5 1 5 7 18 5 18 7 1 18 18 19 19 20

So the new code ready to transmit is the bottom string of numbers. Then, to make the decryption more secure the operator took the meaningless list of numbers and laid them out in a similar format to the original message. They are given a second transformation to give some poor code breaker a headache trying to work out what the key phrase was in the first place. We will omit the second transform to keep things simple and avoid your headache getting worse. The meaningless jumble of numbers is then divided into groups of five and tapped out on the Morse key accurately and quickly so that an enemy’s direction finders cannot locate the agent’s transmitter. It would take an expert at decryption weeks to work out the meaning of the message if they did not know the key phrase.

Back at the control centre the operator had to receive and record the message the agent has sent absolutely accurately for decoding. Any inaccuracy in receiving the coded message could render it meaningless. The message would be decoded simply by reversing the agent’s process of ciphering beginning with the key phrase they shared THANKS FOR SOMETHING. The controller knew the code phrase had its eighteen letters representing the number and order of columns of number/letters in the grid. He (or she) is able to replace the long string of number/letters and lay them out in the right order in their columns

If you wish to understand the enciphering procedure better but do not want to get into the complexity of numbers just omit the numbering aspect of coding and work out a transformation in letters. A single transform in letters would have taken the German code breakers no time at all to work out. The above is an example of a fairly simple cipher but the variations can get so complex that they can defeat the cleverest code breakers. If you are a radio agent hiding in a cold windswept barn in the country and listening for the Gestapo to arrive, you probably cannot cope with further complexities than that above. Just to make the understanding of the message even more difficult for the enemy you will probably use code words for an operation or an individual within the message.

Try your hand at working out what the message is here:

The code phrase is: DOG NEEDS DINNER

The numbered code sequence is:

3.8.5.18 11.2.23 18.15.9 4.18.9.5 4.14.7.15 1.19.1.11

Code words were universally used in the Second World War to refer to any major operation or unit, so each major military, naval or air operation had a security name allocated to it (the author’s code word was BLOSSOM). Ultra was a code name (although it was too secret to be included in the manual) allocated to signals intelligence coming from Bletchley Park and other sources in the British intercept and decryption system. For security’s sake it should not have been possible to guess an operation’s nature by reading the code word in a document or transmission if it fell into enemy hands. Why someone broke this unwritten rule and assigned the code word NEPTUNE to the Allied landings in Normandy or SEALION for the German invasion of England we shall never know. Every code word had to be approved and listed so that a copy of The Authorised Code Word Manual in use at the end of the war was a substantial book containing thousands of code names with their associated meanings. If a copy of the book had been lost, stolen or strayed into unauthorised hands it would enable the reader to not only understand the significance of the code word or phrase but also a description of the operation it represented.

To summarise, a code is a signal of some kind that has a prearranged significance for both the sender and the receiver, and the meaning is held in memory or a code directory.

Interceptions and Encryption

The battle for supremacy between code makers and code breakers began between the armies of Europe before the First World War, when intercept bureaux were devising more sophisticated ciphers and their code-breaking adversaries tried increasingly devious ways to read the messages. Code making and breaking activities would prove ever more important as the war progressed, so cryptological bureaux in combatant and even neutral countries grew from small ad hoc groups of ‘boffins’ to larger and larger specialist military installations as their workload increased. As the importance of their work became more apparent, they were integrated into the hierarchy of military or naval formations and became a part of those organisations. Before the advent of wireless, the problem for cryptanalysts was that there had not been enough intercepted messages to be able to create a body of coded documents to analyse in order to break their ciphers. (Capturing many French despatches, Spanish guerrillas during the Napoleonic wars helped Wellington’s cryptographers considerably.) As wireless messages became the standard method of communicating between units, the reverse problem then arose of how to cope with the great flood of intercepted messages. Senior military officers slowly accustomed themselves to communicating by the use of encoded Morse radio messages until they began to fill the ether. Signallers were having to encipher all messages they had to send out and then decoding the answers, increasing a signaller’s workload tremendously. It also increased demands on the radio signaller’s skills to not only decipher messages but also observe security precautions in his transmissions. The signals intelligence war had begun.

It started with amateur operators who may not have had anything better to do than listen to transmissions which they began to realise came from the enemy. The interception of these transmissions began to be more organised as the war progressed and listening stations were built to intercept enemy transmissions. The Germans built twenty fixed listening stations around their borders as war approached, of which Lauf, near Nurnberg and built in 1939, was an important one. This Fixed Listening Station (Feste Nachrichten-Aufkarungsstelle (FENAST) number 00313) in the Wehrmacht network was where Wilhelm Flicke was Director of Analysis during most of the Second World War, although his cryptographic career had started during the First World War in 1917. Lauf began operating just before war began and was originally meant to cover the military radio traffic from Czechoslovakia but around Christmas 1939 much wider targets were assigned to it in both the Middle East as well as France and the English regions. The station’s designation was changed in the 1942 major signals intelligence reorganisation to Laufer Haberloh. A direction-finding site was built in conjunction with the listening post and there were some fifty manned intercept positions, all of which had three radios and two Morse tape strip recorders each working round the clock in six hour shifts. Breaking codes was not just an Allied achievement at Bletchley Park, German code-breaking results increased as the war proceeded to quite high levels, particularly at a tactical level, although unfortunately many archives showing their progress were largely destroyed during the bombing. One code breaker of renown who was a cryptologist well before 1914 and known to Flicke in the Nachrichtenwesen (German Signals Service) was Professor Foeppi of Munich University. His team of code breakers were, according to his account, able to crack Royal Navy ciphers regularly during the First World War.