Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: 404 Ink

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

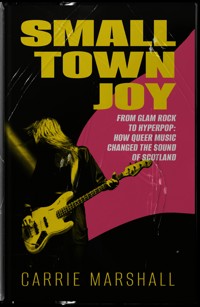

Queer musicians have long mined beauty from the darkest of seams – and today's artists are taking that treasure and using it to make magic. In Small Town Joy, trans writer, musician and broadcaster Carrie Marshall discovers the sometimes surprising ways LGBTQ+ artists changed Scotland's soundtrack, meeting Scots artists, industry insiders and music fans to celebrate the music and musicians that filled floors, opened minds and changed lives. Featuring interviews with Shirley Manson (Garbage), Lauren Mayberry (CHVRCHES), Sean Dickson (HIFI Sean), Maya Evan MacGregor and many more.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 373

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

SMALL TOWN JOY

Published by 404 Ink Limited

www.404Ink.com

All rights reserved © Carrie Marshall, 2025.

The right of Carrie Marshall to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be: i) reproduced or transmitted in any form, electronic or mechanical, including photo-copying, recording or by means of any information storage or retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the publishers; or ii) used or reproduced in any way for the training, development or operation of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, including generative AI technologies. The rights holders expressly reserve this publication from the text and data mining exception as per Article 4(3) of the Digital Single Market Directive (EU) 2019/790.

Please note: Some references include URLs which may change or be unavailable after publication of this book. All references within endnotes were accessible and accurate as of February 2025 but may experience link rot from there on in.

Excerpt of ‘Love’ by Edwin Morgan (Centenary Selected Poems, ed. Hamish Whyte, 2020) is reprinted by permission of Carcanet Press and the Estate of Edwin Morgan.

Editing: Kirstyn Smith

Copy editing: Heather McDaid & Laura Jones-Rivera

Typesetting: Laura Jones-Rivera

Cover design: Kara McHale

Co-founders and publishers of 404 Ink:

Heather McDaid & Laura Jones-Rivera

Print ISBN: 978-1-916637-00-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-916637-01-6

EU GPSR Authorised Representative

LOGOS EUROPE, 9 rue Nicolas Poussin, 17000, LA ROCHELLE, France

E-mail: [email protected]

404 Ink acknowledges and is thankful for support from Creative Scotland in the publication of this title.

SMALL TOWN JOY

From glam rock to hyperpop:

how queer music

changed the sound

of Scotland

CARRIE MARSHALL

For Sophie and Adam,

the beats of my heart;

and in loving memory of Mum,

who would have been so proud.

“Love rules. Love laughs. Love marches. Love

is the wolf that guards the gate.

Love is the food of music, art, poetry. It

fills us and fuels us and fires us to create.”

Edwin Morgan, ‘Love’, from Love and a Life

Contents

A note on language and content

Introduction

Chapter 1: Call me a sin

Chapter 2: A matter of gender

Chapter 3: The heather’s on fire

Chapter 4: I feel love

Chapter 5: Coming down the line

Chapter 6: And she smiled

Chapter 7: A jock with an act

Chapter 8: The party’s over

Chapter 9: Don’t be afraid of your freedom

Chapter 10: The queerest of the queer

Chapter 11: In the beginning there were answers

Chapter 12: A genie in a bottle

Chapter 13: It’s okay to cry

Chapter 14: Rebel girls

Chapter 15: The tide is at the turning

Chapter 16: Chosen family

Chapter 17: Criminal records

Chapter 18: Sunny delight

Chapter 19: Young hard and handsome

Chapter 20: You could have it so much better

Chapter 21: Dreaming of the queens

Chapter 22: Fright club

Chapter 23: Men like wire

Chapter 24: Are you awake?

Chapter 25: The sound of young Scotland

Celebrate: a playlist

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

About the author

A note on language and content

In this book you’ll find me, and others, using the word “queer” a lot. It’s not a word used lightly, because it’s a word with a terrible history of being used against us. But it’s also a word that since the early 1970s has been defiantly reclaimed by the very people it had been used against – “We’re here! We’re queer! Get used to it!” – and which today is used proudly, much like other marginalised communities have reclaimed the slurs once used to dehumanise them.

Reclaiming such words is intended to draw the sting, to drain those words of their poison, to take them back from people who have no right to use them. “Queer” is used in these pages in that spirit. I apologise if that makes some parts of this book difficult for some readers.

As an umbrella term to describe people who don’t correspond to stereotypical ideas of gender and of sexuality, “queer” is really useful when you’re writing about musicians who are no longer around to tell you who they are. Our understanding of gender and sexuality is much more nuanced today, so while many of the people you’ll encounter in these pages might not have defined themselves using words such as pan, trans, non-binary, asexual or gender-fluid, or would have interpreted some of those descriptions differently than we do today, or may have used words that have since fallen out of favour, they lived lives where their sexuality, their gender presentation, or both, would clearly have fitted under the queer umbrella. Because it’s such an inclusive term, it enables me to describe people without trying to force labels onto them that they might well have rejected.

For simplicity and readability’s sake, I’ll be using the acronym LGBTQ+ as shorthand for everybody under the queer umbrella unless I’m directly quoting someone else. I know some people prefer longer acronyms such as QUILTBAG (queer/questioning, intersex/indigender, lesbian, trans/transgender/two-spirit, bisexual, asexual, gay/genderqueer/gender non-conforming) or LGBTQQIP2SAA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex, pansexual, two-spirit, asexual, and ally), but I find that they take me out of whatever I’m reading. QUILTBAG sounds like it should be a BBC Two sitcom where the lead character keeps breaking the fourth wall and talking to the viewer, while LGBTQQIP2SAA feels to me like the name of a TikTok band whose music largely consists of glitchy videogame music and autotuned screaming.

As for the content, Small Town Joy is primarily about love, pride and joy, but, of course, any book about LGBTQ+ people is going to talk about some very dark events and include some terrible things said and done by terrible people. Reader discretion is advised.

Introduction

All your favourite music is queer.

I should probably explain.

The music you love might not be made by queer musicians, or be made specifically for queer listeners, or address queer themes, but queerness is in its DNA.

Queer people have been making music for as long as there has been music. Tchaikovsky,1 Chopin,2 Schubert,3 Handel,4 and Britten5 are all believed to have been gay or bi, and while western pop and rock music quickly distanced itself from its primarily Black and queer roots, almost all of it owes its existence to the raucous “bulldaggers” of 1920s Harlem, the masculine-presenting Black lesbian blues and jazz singers who messed with gender roles and put queerness at the centre of their most celebrated, most sexual songs, and to the music made by the queer Black musicians that would follow them.

In the 1930s, Sister Rosetta Tharpe, a bisexual woman, took queer and gospel music and created rock’n’roll. She forged a template mixing the sacred and the profane that would be made even more explicit in the 1950s by two queer artists, Minnie Willie Mae “Big Mama” Thornton and former drag queen “Little” Richard Penniman, who first performed as Princess LaVonne.

Penniman’s image and act were borrowed from and shaped by two queer performers who were known as The Prince of the Blues and The Queen of Rock’n’Roll respectively. The prince was Billy Wright, a gospel singer and female impersonator who would perform in drag at the tent shows of the time, refining the make-up skills and tricks he would pass on to Penniman; and the queen was a kinetic, dramatic piano player born Eskew Reeder, Jr. but much better known as the bewigged, heavily made-up Esquerita. Esquerita was the pioneer – he would later be credited by the B-52’s Ricky Wilson as a key musical influence and both Mick Jones of The Clash (on Big Audio Dynamite’s ‘Esquerita’) and Adam Ant (‘Miss Thing’, from Ant’s Vive Le Rock album) would write songs about him – but Penniman was the one who would become a musical legend and influence legions of musicians.

Both Thornton and Penniman had to be toned down for mainstream success, something that many recent LGBTQ+ musicians are familiar with. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, the songwriters of ‘Hound Dog’, argued over Leiber’s insistence that the chorus should say, “You ain’t nothing but a motherfucker”, while Dorothy LaBostrie was given the job of taming Little Richard’s ‘Tutti Frutti’. There are differing accounts of the original lyric, which began, “Tutti frutti / good booty” and then was either, “If it don’t fit, force it / you can grease it, make it easy” or, “If it’s tight, it’s all right / and if it’s greasy, it makes it easy”. Either way, it’s safe to say the 1950s America that lost its shit over a straight white man wiggling his hips wasn’t quite ready for that.

Even in their bowdlerised form, ‘Hound Dog’ and ‘Tutti Frutti’ are among the most lewd, lascivious and life-affirming songs ever recorded – and among the most important and influential too.

Those songs and their creators inspired everybody from The Beatles to David Bowie. If it weren’t for ‘Hound Dog’ we might never have heard of Elvis and the future of pop could have turned out very differently; and if it weren’t for Sister Rosetta and Little Richard, we may never have had anybody else. Ringo Starr was in the audience for Tharpe’s English shows and describes Little Richard as his hero; the other Beatles adored Little Richard too, with John Lennon teaching Paul McCartney how to emulate Richard’s trademark howl. “It blew my mind,” Lennon recalled.6 “We’d never heard anybody sing like that in our lives.”

Lou Reed was a Little Richard fan,7 as was David Bowie. Speaking in 1991 about Richard, Bowie said, “Without him, I think myself and half my contemporaries wouldn’t be playing music.”8 Richard was also a formative influence on The Who’s Pete Townshend, who has described himself as pansexual. Speaking about his 1966 song ‘I’m a Boy’, he said that at the time he had to couch songs of queerness and gender confusion “in vignettes of humour and irony.”9 Townshend, the Little Richard-loving Beatles and the gender-bending, bisexual Bowie would prove to be just as influential as their heroes, and had a huge impact on many of the musicians you’ll read about in these pages.

That impact was more than musical. The Beatles may not have been queer – according to Yoko Ono, John Lennon believed we’re all “born bisexual”10 although he never experimented – but their image was considered to be unacceptably so by many conservatives. That image, shaped largely by their gay manager Brian Epstein, was scandalously androgynous by the standards of the time. Feminist writer Betty Friedan described it as a rejection of, “that brutal, sadistic, tight-lipped, crew-cut, Prussian, big-muscle, Ernest Hemingway”11 machismo particularly prevalent in the US, while one US Pentecostal writer was so furious about their apparent femininity that he took to his typewriter to exclaim, “No matter how popular the Beatles become, American girls still like boys to look like boys.”12

LGBTQ+ people were just as influential offstage. In the 1950s Larry Parnes, a gay man, created the first British rock star, Tommy Steele, and transformed multiple boys-next-door into pop stars with a change of name and some better clothes: Steele was born Thomas Hicks, Ronald Wycherley became Billy Fury and Clive Powell became Georgie Fame. Parnes also invented the rock concert tour, where a bus full of bands travelled the country to play just one night in each town. Parnes’ uncanny ability to spot the stars of the future – he was the most successful British music manager of the 1950s and 1960s – only failed once, in May 1960. Parnes had given a young band called The Silver Beats the job of supporting Johnny Gentle at dates in Alloa, Inverness, Fraserburgh, Keith, Forres, Nairn, and Peterhead. They performed as The Johnny Gentle Band and adopted stage names: Paul Ramon, Stuart de Staël, Carl Harrison, and Long John. However, despite their excitement, their first “showbiz” adventure was short-lived: Parnes decided not to continue working with them. The band went back to their given names: Paul McCartney, John Lennon, George Harrison, and Stuart Sutcliffe, and The Silver Beats became The Beatles.

Parnes was the first of what would later be dubbed the “velvet mafia”, the gay managers, producers and music moguls of the late twentieth century who knew exactly what and who would sell to teenage girls. They shaped the careers and images of artists ranging from Billy Fury, Marc Bolan, The Beatles, and The Bee Gees to Wham! and The Who, effectively inventing pop culture as we know it today.

That culture may have tried to hide its queer roots – and in those much less enlightened times, many artists certainly had to hide their love away. But you can’t hide your love forever, and queerness came swaggering and strutting out of clubs in the 1970s to take its place not just in disco, but also in US punk and new wave. Disco would fuel dance, electronic and pop music forever, and the punk music – named after a term originally used by Shakespeare to describe sex workers of any gender, but more usually used for men – of Lou Reed’s Velvet Underground and of The New York Dolls would influence rock and indie musicians from The Sex Pistols to The Smiths, Green Day to Guns’n’Roses, Misfits to The Manic Street Preachers. On this side of the Atlantic, the fuse of the UK punk explosion was lit in the gay clubs of London.

By now you’re probably thinking: This is a book about Scottish music. What does any of this have to do with Scotland?

Music is a story, and we Scots are among the world’s finest storytellers. We tell our children tales of selkies and kelpies, supernatural and shape-shifting creatures of magic and mystery, so it’s only natural that our music would be full of magic and mystery and shapeshifters too.

Scots have a long history of moving things and people around the world; if England is a nation of shopkeepers, Scotland is a nation of shipbuilders. And when you move people and things around the world their music – our music – moves with them. When music moves, it finds new shapes to take, new songs to sing and new voices to sing them.

Today, beats made in Bellshill bedrooms can be trending on TikTok by teatime. But while that speed is new, the motion isn’t. My kids’ music travels at the speed of light through fibre-optic cables, but my music travelled too: it came to me on cover-mounted cassette tapes and over the airwaves from far away and fading FM stations. For the generations before, music travelled from the other side of the world, on shellac and vinyl discs brought to Britain in the cavernous cargo holds of giant ships.

When music travelled by ship and by sea, the songs of innovators would be inhaled by imitators across the water and sometimes exhaled in whole new shapes. Those shapes would then make the return trip and influence the influencers, setting the next stage in motion.

Much of that music came through Scotland, often on Scottish-made ships: in the 1900s, one-fifth of the world’s shipping fleet was built by Clydesiders. Glasgow in particular was one of the world’s busiest ports, dubbed the “second city of the British Empire”, and as products and people moved through Glasgow, music moved with them.

That imperial history is not without its horrors. Many Scots emigrants would become slave owners, and Glasgow merchants grew obscenely rich on the backs of the Black slaves who harvested tobacco and sugar in distant plantations. Major Glaswegian streets bear those merchants’ names today, a history Glasgow is only just starting to face up to.

But there are happier stories too. For example, if you’ve ever wondered why US country music is so incredibly popular in Scotland, and in the west of Scotland in particular, it’s because we helped invent it.

US country is the music of the melting pot, and Scots were a key ingredient: in our many decades of emigration to North America, with more than 360,000 Scots boarding Clyde-built ships to travel to the US and Canada in the 1920s alone, we took our folk music across the Atlantic. There, it joined hands with other forms of music including Irish and German folk music and Black spirituals, creating a style that would bring us artists ranging from Charley Pride and Johnny Cash to Lil Nas X and Jimmy Shand.

According to US academic and musician Dr Willie Ruff, those Black spirituals may have incorporated Scottish influences too: the “lining out” singing style of nineteenth-century Black slaves is sonically very similar to the “presenting the line” hymns of Hebridean Scots, thousands of whom emigrated to the US in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

As for the self-proclaimed King of Country, Johnny Cash, perhaps the Man in Black could have been The Man in Black Watch: Cash believed his family originally hailed from the Kingdom of Fife.

As you’ve probably guessed from the weight of the paper, the size of the e-book or the time markers on the audiobook, Small Town Joy isn’t going to tell the entire story of Scots music. Instead, I want to tell you a story: one of music loved by and made by LGBTQ+ Scots that queered the mainstream, influencing generations of musicians and music fans both here and all around the world.

I’ve experienced Scotland’s music scene in two different roles (as a musician and as a music fan), in two different time periods (the late nineties/early aughts and today) and two different genders (man and woman). I’ve seen big changes in LGBTQ+ acceptance and visibility in that time, and today’s scene is a very different place for women and LGBTQ+ people than it was in previous decades. That difference isn’t just in my favourite genres, pop and rock. It’s in everything from trad to techno. That’s something I find absolutely fascinating, and I hope you will too.

What I’ve come to understand is that in music, queerness is like glitter. It makes everything sparkle, and it gets everywhere.

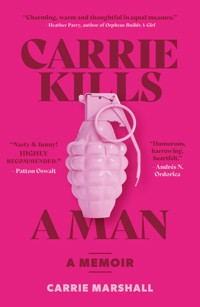

I started work on Small Town Joy while promoting my trans memoir, Carrie Kills a Man. In that book I say that the recipe for people is like the recipe for minestrone: apparently simple, but capable of almost infinite variation. I think you can say the same about music.

Almost all music can be boiled down to just three crucial ingredients: rhythm, melody and harmony. Yet, in musicians’ hands it becomes so much more. Especially when those musicians are queer.

Queer music is outsider music, and outsider music comes bearing more than just melody on the back of its beats. Outsider music is music with baggage, with bruises, with battle scars. Those are its base metals, and queer musicians somehow manage to turn those metals into gold.

The joy of queer music is all the more remarkable when it’s so often forged in the most terrible fires. But that’s what makes it so powerful too, why its love and its lust, its defiance and its desire, its escapism and its euphoria feel so transcendent and so vital.

What queer music tells you is the most important thing of all:

You are not alone.

For a book about joy, there are a lot of tears in Small Town Joy. But they’re mostly the tears I cry at the back of the Barrowlands when the emotion overwhelms me, the tears I cry when Kim Carnie sings so beautifully about her “walking disaster” of a girlfriend in ‘She Moves Me’, the tears I cry when Man of the Minch sings mournfully in ‘Mountains’, the tears I cry when SOPHIE tells me that ‘It’s Okay to Cry’.

They’re the tears I feel starting to well up when the glassy notes of a DX7 synth tell me that Jimmy Somerville is going to make me cry myself inside out all over again.

I’ll come back to Jimmy shortly, and to all these other incredible musicians. But first we need to go to a much darker place.

Chapter 1: Call me a sin

For many queer Scots in the 1970s, the best thing about the country was the railway tracks leading out of it.

Scotland may have been voted the best place for LGBTQ+ people to live in 2015 and 201613 – an accolade it has shamefully lost in recent years, falling to seventeenth place in 2023 – but in the decades and even centuries before, Scotland was definitely not glad to be gay.

We like to joke about members of the Wee Frees chaining up swings on a Sunday, but Scotland has long been a very religious country with a distinctly puritan streak on both Presbyterian and Catholic pews.

Scotland is now officially a secular country. The 2022 Scottish Census found that 51.1 percent of Scots had no religion, up from 36.7 percent in 2011, and the numbers of people who practice religion of any kind is much smaller. Christian church attendance has been in decline for many years – so much so that since 2023 the Church of Scotland has been selling off hundreds of churches, manses, halls, and cottages as attendance falls. Its membership declined from over 900,000 people in 1982 to just over 270,000 in the early 2020s and the average age of a congregant is 62. The Catholic Church is in decline too: in 1982 it had 273 men in training for the priesthood; in 2022 it had just twelve. Despite a recent boom in the number of Scots getting married, religious marriages now account for fewer than one-third of Scots marriages. We’re far more likely to have, or attend, a humanist or civil ceremony.

This change has been slow, though, and slower than in England; Scotland’s move towards secularism didn’t really accelerate until the late 1960s and into the 1970s when multiple civil rights movements – notably feminism and gay rights – and technologies such as the contraceptive pill challenged the churches’ grip. But the grip remained strong for a long time, and even today Scottish councils must by law have three religious representatives on their education committees, including one from the Church of Scotland and one from the Catholic Church. These unelected figures get a say in policies such as relationship and sex education in non-religious schools, and in which schools councils decide to save or shutter. Eight Scottish councils have removed religious representatives’ voting rights since the controversial closure of Blairingone Primary School in Kinross-shire in 2019, when the committee’s two religious representatives swung the vote from save to shut. 24 councils haven’t.

Religion’s hold on Scotland’s society, politics and press perhaps helps to explain why it took us fourteen years longer than England to decriminalise consensual sex between two men, which England and Wales did in 1967 but Scotland didn’t do until 1980.14

Lesbians were never criminalised by anti-gay legislation – in 1921 the House of Lords rejected calls to prohibit any “act of gross indecency between female persons” for fear of giving women ideas: “The more you advertise vice by prohibiting it the more you will increase it”; peers also suggested that such prohibition would be unfair because “women are by nature much more gregarious”15 – but man-on-man action was outlawed during the reign of Henry VIII in 1533 and remained punishable by death in England until 1861. Scotland took even longer to change the law, becoming the very last part of Europe to abolish the death penalty for gay sex, which it finally did in 1889. And even when execution was off the menu throughout Britain, gay men could still be imprisoned – as Oscar Wilde was in 1895 – or subjected to chemical castration, as computer pioneer Alan Turing was in 1952.

The legal climate began to change in the late 1950s when, after three years of investigation, the Wolfenden Report recommended that the government should decriminalise homosexual activity. That was in 1957. It took another decade for England to act on that recommendation and another two decades for Scotland to follow suit. Gay sex wasn’t decriminalised here until the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act, which became law in 1980 but didn’t take effect until February 1981.

Even then, Scotland didn’t fully decriminalise gays having fun. We kept the same caveats as the English decriminalisation of the 1960s: gay sex remained illegal for men under twenty-one, for men who had sex in a hotel room or for men who had sex when a third person was present or participating. The age of consent wasn’t lowered until 1994, but even then it was only lowered to eighteen. Full equality didn’t happen until 2001, and equal marriage didn’t hit the statute books until 2014.

Some of our politicians, such as Scotland’s current Deputy First Minister Kate Forbes, say they would have voted against Scotland’s equal marriage legislation;16 others, such as Tory leadership candidate Murdo Fraser, was one of eighteen MSPs who did vote against it and says today that he is still opposed to it.17 The SNP-led Scottish government resisted calls for equal marriage legislation for many years, arguing that the civil partnerships introduced in 2005 were enough, and equal marriage only became law in Scotland after David Cameron’s Tories introduced equal marriage legislation for England and Wales in 2013. Even then, both the Catholic Church and Church of Scotland were in opposition and David Robertson, minister of St Peter’s Free Church in Dundee, told the BBC, “We will now be discriminated against when we do not bow down to the new State absolutist morality… this will be detrimental to the people of Scotland, especially the poor and marginalised.”18

That was in supposedly progressive 2014. Imagine what 1974 must have been like.

For queer musicians in the 1970s, the safest place in Scotland may have been the closet. The culture offered at best smirking homophobia and at worst serious danger.

There were a number of gay clubs, most notably in Edinburgh where the city’s pioneering gay disco, at Nicky Tams on Victoria Street, became so busy that the scene moved to much larger venues such as Tiffany’s on St Stephen Street. However, some people in their late teens who were below the then-unequal age of consent say they were made to feel distinctly unwelcome by the older patrons. Queer people of all ages seeking company faced multiple dangers, including entrapment by plainclothes policemen and violence in the streets.19

It’s hardly surprising that, in this climate, few if any LGBTQ+ musicians were willing to go public about their sexuality. Billy Lyall, the multi-instrumentalist who was an early member of The Bay City Rollers and who co-wrote Pilot’s first hit single, ‘Magic’, was gay, but kept his sexuality quiet; he was outed a decade after his death from an AIDS-related illness by his former manager, Thomas Dougal “Tam” Paton.

As with K-pop bands in the early 2000s, The Bay City Rollers had a frequently changing lineup of young, good-looking, supposedly virginal musicians whose squeaky-clean image was so crucial and so controlled that even having girlfriends was banned. Paton wouldn’t have dreamed of outing Lyall or any other Roller in the 1970s: in the Rollers’ world, all the boys were perfectly pure and as straight as straight can be.

But Paton’s Rollers also featured at least one other closeted LGBTQ+ person, lead singer and teen girls’ heartthrob Les McKeown. McKeown stayed in the closet until Paton’s death in 2009, after which he publicly came out as bisexual and started talking about what had happened to him in the band.

Young closeted LGBTQ+ people can be very vulnerable, and that attracts predators – predators like Paton. He used his power and status to abuse multiple young men including teenage runaways, boys who’d been placed in care, would-be pop stars, and some of his charges, who he plied with alcohol and drugs to make more receptive. Three of the Rollers – McKeown, guitarist Pat McGlynn and original singer Nobby Clark – have said they were among his victims. In a 2023 documentary about the band and their manager, McGlynn said that Paton was “a monster… in the seventies, there were people who had the right to do what they wanted with you.”20

Les McKeown died in 2021. In her report, senior coroner Mary Hassell noted that the singer had a markedly heavy heart,21 and said damage from his lifelong struggles with alcohol and drug abuse were significant factors in his death. Those struggles dated back to McKeown’s days as a Bay City Roller; he was abusing alcohol and cocaine while teen magazines reassured their readers that the strongest substance their idols enjoyed was milk.

It seems that many LGBTQ+ musicians of the era faced Hobson’s choice: come out and say goodbye to your career and possibly your safety; stay in the closet and risk blackmail or worse.

That was definitely something Wendy Carlos believed. Carlos introduced the world to (and contributed to the development of) the Moog synthesiser, had a huge global hit with her 1968 album Switched-On Bach, and was also an early proponent of what we now know as ambient music. Her soundtracks for A Clockwork Orange, The Shining and Tron were critically acclaimed, musically stunning and hugely influential.

Carlos was a huge influence on other important figures including John Carpenter – “That’s where I think it started,”22 Carpenter said, crediting Switched-On Bach with fuelling his love of synth music – and Giorgio Moroder. The godfather of modern dance music, Moroder was inspired by Carlos to pick up a synthesiser, and without Carlos’ influence there would have been no ‘I Feel Love’, no ‘Love to Love You Baby’, no ‘Call Me’, no ‘Number One Song in Heaven’. It’s not hyperbole to say that without Carlos, electronic music – especially pop and dance music – and movie soundtracks would be very different. CHVRCHES albums would certainly be a lot shorter.

Carlos is a trans woman who transitioned in 1972, but like other trans people of that era – such as the Emmy award-winning conductor and Watership Down composer Angela Morley, who transitioned the same year and decided she was no longer willing to appear on TV for fear of a negative reaction – she spent many years avoiding the spotlight. She would later say that she lost an entire decade hiding her true self from fame, refusing visits from famous fans including George Harrison and Stevie Wonder for fear of public ridicule. This was so strong that before what would be her final live concert, she decided that she wanted the audience to think she was a cisgender man. Carlos applied fake sideburns and drew on fake stubble, crying in her hotel room as she donned her disguise.

“There had never been any need of this charade to have taken place,” she would later recall. “The public turned out to be amazingly tolerant or, if you wish, indifferent […] It had proven a monstrous waste of years of my life.”23 But there were still many indignities, accidental or otherwise, because of her trans status; the 2001 rerelease of her Clockwork Orange soundtrack credits her under her deadname.

The electronic instruments that Carlos loved would play an important part in one of the three key musical movements of the 1970s, two of which rejected the largely macho swagger of what we’d now call classic rock. That movement was disco, which emerged in New York from the Black and gay rights movements and which mixed R&B, soul, synthesisers, and propulsive four-to-the-floor beats to thrilling effect.

The other standout anti-macho musical movement was UK punk, which took the Marlon Brando attitude to rebellion: when asked, “What are you rebelling against?” the reply would be, “What’ve you got?” Punk wanted to get drunk and destroy everything about the status quo from the po-faced proficiency of Pink Floyd to the patriarchy.

Last but not least, there was hard rock, which was transitioning to become heavy metal.

There’s some distance musically between ‘Rock the Boat’ and Combat Rock. But disco and punk had a lot in common. While both scenes would ultimately be colonised and homogenised by very different demographics, they both initially emerged from disenfranchised communities: Black, LGBTQ+ and Latin groups in the US, and poor, working-class areas in the UK. Both scenes rejected the often oppressive societal and musical norms of the time and cast their nets widely: the foundational track of disco, ‘Soul Makossa’, was an import from Cameroon, and much of UK punk was heavily influenced by Jamaican reggae and dub. Both scenes faced significant opposition from the establishment. And both would be enormously influential for decades to come.

As Darryl W Bullock writes in his superb book Pride, Pop and Politics,

“The birth of British punk rock (as opposed to the American version) is inextricably linked to London’s gay scene. When no venue would consider hosting punk bands or allowing them to practice there, it was the underground gay clubs of Covent Garden and Soho that provided space. When every other public house refused to serve these weird-looking kids with their spiky hair, outrageous make-up, torn clothing and safety-pin jewellery, it was London’s gay clubs [that] embraced them. And when they needed a hangout of their own, it was a gay club, Chaguaramas, that became The Roxy, London’s premier punk venue.”24

One of the most infamous groups of English punks was The Bromley Contingent, followers of The Sex Pistols whose numbers included Billy Idol, Siouxsie Sioux and Steve Severin, later of Siouxsie and The Banshees. Many of the contingent were gay, and, as Siouxsie recalls, the period was “a club for misfits, almost. Anyone that didn’t conform to any mass Mecca to belong to, it was waifs, there was male gays, female gays, bisexuals, non-sexuals, everything. No one was criticised for their sexual preferences. The only thing that was looked down on was being plain boring.”25

After disco and punk, the third genre was heavy metal, which in the early seventies was moving away from its blues-rock roots into something much harder. That was largely down to Judas Priest, the band credited with inventing the genre as we know it, thanks to their use of double-pedalled kick drums, Rob Halford’s distinctive, octave-spanning vocal style and their then-blasphemous use of synthesisers. From Metallica to Slipknot and even the parodic Spinal Tap, if it’s metal or one of metal’s many subgenres, it owes a debt to Priest.

Judas Priest’s influence wasn’t just musical. Halford made the leather, spikes and studs of the gay and BDSM scenes his stagewear, a look that was widely copied by many macho men of glam rock and metal on both sides of the Atlantic. Halford wouldn’t come out until 1998, but it’s fair to say he was dropping some pretty big hints during the two decades prior.

It’s said that everybody who saw The Sex Pistols play Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall in the summer of 1976 formed a band. For many Scots musicians, their year zero came slightly later in May 1977 when The Clash came to the Edinburgh Playhouse on the White Riot tour. As Vic Galloway writes in his book Rip It Up, the show would “instigate a Scottish post-punk revolution in its grand surroundings. Members of Orange Juice, Josef K and The Fire Engines were all in attendance and experienced an epiphany.”26 While the bill also featured The Jam and Subway Sect, it seems that the two acts with the biggest impact were Buzzcocks and The Slits.

Buzzcocks’ Spiral Scratch EP, recorded with original singer Howard Devoto, is one of the most important records of what came to be called post-punk. But Buzzcocks’ imperial phase began when Devoto quit in the spring of 1977 after fewer than a dozen gigs and was replaced by Pete Shelley (born Peter McNeish; Shelley was the name his mum would have called him were he born a girl).

Shelley, who was bisexual, wrote songs that were impishly playful, sometimes hilariously sexual and always incredibly relatable – and while he didn’t release anything openly queer until his solo record ‘Homosapien’ in 1981 (featuring the wonderful couplet ‘Homo superior / in my interior’), his sexuality was hardly hidden. When the band appeared on Top of the Pops in 1978 to perform ‘Love You More’, Shelley’s guitar strap bore a large badge emblazoned with the words “I LIKE BOYS”. More eagle-eyed viewers might also have spotted another, which read, “How dare you presume I’m heterosexual?”

Buzzcocks’ ‘Ever Fallen in Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)’ is rightly regarded as one of the greatest pop singles ever recorded. It’s queer as hell, the LGBTQ+ ‘Teenage Kicks’. Inspired by the Marlon Brando movie Guys and Dolls, which Shelley saw while relaxing post-gig in Edinburgh’s Blenheim Guest House in late 1977, the song is about Shelley’s relationship with Francis Cookson, the man he lived with for seven years. Viewed through a queer lens, the chorus is even more poignant: which queer person hasn’t fallen in love with someone who couldn’t or wouldn’t love them back? I’m usually in double figures by lunchtime.

Shelley didn’t hide his bisexuality, but I think he encrypted it: queer musicians, like other marginalised artists, often hide their selves in plain sight for mainstream listeners to ignore and queer folks like me to overanalyse. It’s there if you know to look for it. Among the lists of masturbatory subjects in ‘Orgasm Addict’ there are “butcher’s assistants and bellhops”, and I’ve laughed a lot at online analyses of ‘Why Can’t I Touch It?’ that talk about its lyrical explorations of existentialism and philosophy, when I’m pretty sure it’s The Beatles’ ‘I Want to Hold Your Hand’ rewritten with a very different appendage in mind.

Introducing his interview with Shelley in 1994, Matt Wobensmith of Outpunk fanzine noted, “Of all the British punk bands, the Buzzcocks were perhaps the most obviously open to gay sexuality. That they enjoyed all types of sex was well known, and in his liner notes to the Buzzcocks box set Product, Jon Savage (himself one the queerest of critics) makes a big point of noting that the Buzzcocks were a gay positive band.”27 Asked whether the early punk scene was more inclusive, Shelley replied,

“It didn’t really matter what you were, what sexual persuasion you were from or what gender you were. It was just a chance for everyone to do things, because lots of people were stretching the boundaries of what it was possible to do. So it didn’t really matter, it didn’t raise eyebrows if someone was gay… [gay clubs] were the freer places where you could actually hang out and dress like you wanted and it was ok. If you went to straight clubs, then you got odd looks.”28

I think one of the things that punk offered queer people, as goth and emo would do in the decades following, was a place where you could hide in plain sight by being outrageous: punk was supposed to be provocative and shocking, a rebellion against whatever the older generations had. Queer people were part of that rebellion and queerness was part of that provocation: one of the most famous products ever sold by Sex, the shop run by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren that spawned The Sex Pistols, was Westwood’s “Two Cowboys” T-shirt, which reproduced an erotic illustration by Jim French of two very friendly cowboys. The first person to wear it in public was immediately arrested on grounds of obscenity, which of course was the whole point.

One of the key venues for Manchester’s burgeoning punk movement was The Ranch, which Shelley recalled “was a gay bar really […] gay bars were the places you could go and be outlandish with your dress, and not get beaten up. You could almost get into cross-dressing, without it being a big hassle. People were bohemian, while everybody was trying to conform. Your sexuality wasn’t an issue.”29

Buzzcocks’ influence was immediate and long-lasting, not just musically but in Shelley’s distinctly un-macho stage persona. The Slits’ legacy was a slower burn.

The four women in the band – the classic lineup of Ari Up, Viv Albertine, Tessa Pollitt and Palmolive – were radical enough by simply being four feminists in a punk band. But they also claimed Dionne Warwick Sings Burt Bacharach as their favourite album, and their own debut LP was produced by reggae and lovers rock legend Dennis Bovell. Their extraordinary sound and rejection of gender stereotypes would prove to be enormously influential in queer punk of the 1980s and beyond.

The Slits’ legacy was perhaps at its clearest in the 1990s Riot grrrl movement, whose Scottish contingent included the critically lauded Lung Leg, who split in 1999 before reforming in 2023, as well as more recent Riot grrrls of the 2020s including Tomintoul’s sibling duo Bratakus and Glaswegian quartet Brat Coven. Both bands are fiercely feminist, proudly political and avowedly LGBTQ+ inclusive, and Bratakus have also helped inspire the next generation of grrrls of every gender through their work with Girls Rock Glasgow.

Punk enthused an astonishing group of Scottish artists including Edinburgh’s The Rezillos (who were also strongly influenced by the energetically camp alt-pop of The B-52’s), Scars, The Prats, The Fire Engines, The Flowers, Dunfermline’s Skids and The Exploited – whose Big John Duncan would later play in Goodbye Mr Mackenzie alongside the young Shirley Manson. The scene wasn’t always quite as inclusive as Pete Shelley recalls – Scars would incite a furious response from crowds when singer Robert King took to the stage wearing heels and earrings – but the bands and fans of the time describe it as a golden age of creativity and experimentation.

While the pop fans of East Lothian and Fife scoffed at their big brothers’ prog rock records and embraced punk’s DIY ethic, Glaswegian punks weren’t so fortunate.

Following a riotous show at Dundee Technical College’s student union in early 1976, The Sex Pistols were due to bring their Anarchy tour to the Glasgow Apollo and the Caird Hall in Dundee later that year. Both shows were cancelled as threats to public order; Dundee’s Lord Provost, Chic Farquhar, claimed at the time, “We have enough hooligans of our own without importing them from England.”30

Some members of Glasgow’s licensing committee also wanted to cancel the planned Stranglers show in the City Halls scheduled for June 1977. The show wasn’t banned, but some members, including the Conservative licensing committee chairman Bill Aitken, went along and didn’t like what they saw. As Glasgow’s Lord Provost, David Hodge, put it, “If these people with their depraved minds want to hear this kind of thing, fair enough. But let them do it in private.”31

It’s been widely reported that in 1976/77, Glasgow councillors banned punk rock from Glasgow but, like a lot of stories around punk, it has been exaggerated: there was a short-lived ban, but only in venues that were licensed as theatres such as the Apollo and the City Halls.32 The Burns Howff in West Regent Street and the Mars Bar in Howard Street, among others, put on punk bands such as The Jolts and Johnny & The Self Abusers, who would later become Simple Minds. According to journalist Simon Goddard, “The stark reality of the risk [from putting on The Sex Pistols] was more depressing than terrifying. Before being cancelled, the Apollo had sold less than a hundred tickets. All the punks in Glasgow could barely fill a double-decker bus.”33

The licensing committee may have put pressure on Glasgow’s pubs to not host punk gigs, but it didn’t ban them from doing so. However, for some venues, they didn’t need to.

Many Glasgow venues had enough to deal with without adding punk rock to an already volatile mix. Glasgow was no longer the Mean City of the 1930s razor gangs, but it was still a tough town – and the dancehalls and clubs were notoriously violent from the late 1960s and throughout the 1970s. This was the Glasgow of the Maryhill Fleeto, the Yoker Toi and the Ibrox Tongs, teenage gangs who used the city centre and several of its venues as their battlegrounds.

As if that wasn’t enough trouble, some venues had even more violent patrons: the Barrowland Ballroom, which everybody calls The Barras, became the stalking ground of serial killer Bible John, who murdered three women on their way home from nights out at the venue in 1968 and 1969. These killings were partly responsible for the venue closing in the early 1970s. It reopened as a roller disco and didn’t become a significant venue again until 1983 when Simple Minds used it for their ‘Waterfront’ music video.