18,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

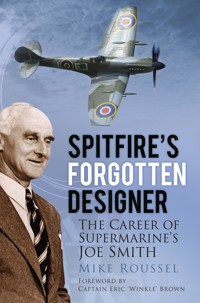

The Supermarine Spitfire was a classic design, well known for its efforts in defending British shores during the Second World War. However, while Reginald Mitchell is rightly celebrated for his original design of the Spitfire, the role of Joe Smith in the development of the Spitfire is often overlooked. Smith was an integral member of the design team from the earliest days, and on Mitchell's death in 1937 he was appointed design office manager before becoming chief designer. Smith's dedicated leadership in the development of the Spitfire during the war, as well as his efforts on post-war jet aircraft, deserve their place in history. Charting the fascinating history of Supermarine from 1913 to 1958, when the company ceased its operations in Southampton, shortly after Joe Smith's death in 1956, this book tells its story through the eyes of apprentices and many other members of Smith's team. Marvellous photographs add to the sense of what it was like to work under Joe Smith at the drawing boards of one of Britain's most famous wartime aviation manufacturers.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

This book, dedicated to all who worked for Supermarine, tells the story of the famous design team and their inspirational and innovative chief designers, R.J. Mitchell and Joseph Smith.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

Foreword

Preface

Acknowledgements

Part I: Reginald Joseph Mitchell (1895–1937), Inspirational Designer

Introduction Flying Like Birds

Chapter 1 The Early Years

Chapter 2 Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd

Chapter 3 Supermarine Flying Boats in the 1920s

Chapter 4 Schneider Trophy Races 1913–1931

Chapter 5 Supermarine Aviation Works (Vickers) Ltd

Chapter 6 Design and Development of the Spitfire

Chapter 7 Early Warnings of the 1930s

Part II: Joseph Smith (1897–1956), Innovative Designer

Introduction Joseph (Joe) Smith

Chapter 8 From Design Manager to Chief Designer

Chapter 9 Development of Photographic Reconnaissance

Chapter 10 The War Years in Southampton

Chapter 11 Supermarine Prepares for Wartime Contingencies

Chapter 12 The Spitfire in the Second World War

Chapter 13 Wartime Apprenticeships

Chapter 14 Air Transport Auxiliary Ferry Pilots

Chapter 15 Test Pilots

Chapter 16 Working Closely with Joe Smith

Chapter 17 Post-War Developments Leading to Jet Aircraft

Chapter 18 Breaking the Sound Barrier

Chapter 19 The Swift World Speed Record

Chapter 20 Landing on Rubber Mats

Chapter 21 Post-War Apprenticeships at Supermarine

Chapter 22 Goodbye Hursley Park

Chapter 23 Memories of Joe Smith

Epilogue

Bibliography

Plate Section

Copyright

FOREWORD

By Captain Eric Brown CBE, DSC, AFC, QCVSA, MA, Hon. FRAeS, Hon. FSETP, RN

Chief Naval Test Pilot, RAE Farnborough, 1944–49

This is a book that just had to be written about a man who made a huge contribution to British aviation in the Second World War but was so self-effacing that he got little recognition for his demanding work, crucial to our war effort.

Stepping into the shoes of an inspirational chief designer at Supermarine would have daunted most men, but Joe Smith took it in his stride and without fuss while keeping the Spitfire in the forefront of fighter excellence. At the same time, he took a deep interest in adapting the Supermarine masterpiece to the naval environment, and so inevitably he and I came into close contact.

Joe took to carrier life like a duck to water and loved to attend deck landing trials of his products, and many an evening we would chat over a horse’s neck (brandy and ginger ale) in the wardroom. He was a good listener and an innovative designer, so he kept the Seafire up with the performance hunt while making it safer and more robust for carrier operations.

By the end of the Second World War, I could see that it had taken its toll on Joe just as a new lease of life was needed to cope with the advent of the jet age. The jet aircraft coming from his drawing board showed his star was on the wane, but I shall always associate his name with the thunderous Seafire 47, which I loved to fly. This book is a tribute to a fine aircraft designer and a great man, whom I shall always remember with respect and affection, for he gave his all to his country, to his company, to the Fleet Air Arm, and to the RAF – with scant reward.

PREFACE

Supermarine Inspirational and Innovative Design Engineers

Whenever the Spitfire is mentioned, the name of its famous designer R.J. Mitchell comes to mind, but few have heard of the man who led the development of the Spitfire throughout the war to become the deadly fighter that the Luftwaffe pilots feared. That man was Joe Smith. Reginald Mitchell sadly died of terminal cancer in June 1937 and was not able to see his prototype design progress into becoming perhaps one of the most famous fighter aircraft of the Second World War. Working under Mitchell as chief draughtsman was Joseph (Joe) Smith who was very involved with the early design of the Spitfire. After Mitchell’s death in 1937, Smith first became manager of the Design Department, and then later chief designer.

There is a British wartime propaganda feature film about the Spitfire called The First of the Few (1942), directed by Leslie Howard, who takes the part of Mitchell in the film. The film is about him working alone to design and build a fighter for the defence of Britain in a future war, and does not refer to any other members of his design team, especially Joe Smith, who worked alongside him on all the design work of the Spitfire right from the beginning.

My own interest in the Spitfire goes back to the war years. When living near Yeovil, Somerset, I remember the searchlights criss-crossing the sky at night, the bombing and the ‘dogfights’ high up in the sky. For some time I lived with my uncle in Westland Road, close to Westland Aircraft Works where he worked. I would spend many hours near the main gates, watching the aircraft taking off and landing, and remember vividly the sounds of the engines as they were tested. My uncle could see how interested I was and bought a model kit, and together we made and flew my first model aircraft.

The idea for a Supermarine book came after talking to Dave Whatley, chief archivist at Solent Sky Aviation Museum, Southampton, who had loaned me some photographs from their collection to use in one of my books. He asked me what I was going to write next, and when I explained that I had not yet made up my mind, said, ‘Why don’t you write about Joe Smith and his work on the Spitfire during the war years?’ I knew that Mitchell had designed the Spitfire, but was unaware of Smith and his leadership in the development of the Spitfire during the war. Dave Whatley told me that for many who knew Joe Smith and had worked within his design team, it was a great concern that there was very little written about his work on the Spitfire, and that credit for his leadership and dedication was long overdue.

I decided to undertake some initial research which confirmed to me that this was an interesting project that I would like to take on. I was able to gain the help of an ex-Supermarine apprentice who introduced me to other apprentices and this led to contact with the sons and daughters of the senior members who had already passed away, and so the list grew. My next task was to undertake the taped interviews, but I heard that Smith had a surviving daughter, Barbara, and after quite some time we made contact and so the story unfolds. All the interviews were recorded with the interviewees’ permission and later transcribed. As quite a few of the interviewees still lived in the local area, I was able to meet them in person. Others, however, were further away, including some in Australia and the USA. These interviews were carried out over the telephone, but were still recorded and transcribed.

Experiences fifty or more years ago are understandably not always recalled accurately in every detail, so dates of events may not always be correct. It was necessary for me to check the factual and historical accuracy, but I was very surprised how accurate many of the interviews were. Furthermore, I wanted to capture and record their experiences in their own words for authenticity, and many of these interviews were backed up by documentary evidence, such as reports, test pilots’ log books, and photographs. Furthermore, I was fortunate to be introduced to a number of people who had worked on the shop floor. Their interviews were very illuminating with regard to what it was like working in the various sheds, their experiences of the Luftwaffe bombing of works, and dispersal after the factory was destroyed.

I am deeply indebted to Barrie Bryant, who lives in Australia, and Murry White, who lives in the USA, for the amount of time and help they have given me over the years for my research. Barrie Bryant loaned me correspondence that he had with ex-Supermariners living in Australia and the UK, and with the permission of their relatives, I have been able to add interesting accounts of their experiences of working for Supermarine during the 1920s and ‘30s. Murry White has been a fount of all knowledge with his experiences of working for Mitchell as his runner, and later as Smith’s technical assistant, and was able to describe vividly his personal experiences at Supermarine.

However, it was not possible to write the book without looking at the development of Supermarine and how the chief designer, Mitchell, started to build his young and talented design team in the 1920s. It was important to also look at how the team grew from small beginnings and the development of the company through to the 1930s when the prototype Spitfire flew for the first time, on 5 March 1936. After Mitchell died in 1937, the design team was seen as a closely knit ‘family’, which did not change after Smith took over as chief designer, successfully leading the team into the jet age until his death in 1956.

Mitchell was a prolific designer and by his untimely death had designed twenty-four different types of aircraft. However, with the prototype Spitfire he delegated the developmental work to Smith and the design team while he set about designing his first bomber. Sadly, he was not able to complete the project before he passed away, and both bomber fuselages under construction were destroyed when the works was bombed in September 1940. It is quite possible that had Mitchell lived, he would have wanted to design another fighter to take over from the Spitfire, but Smith knew that with the threat of war with Germany looming, there was not the time available to design a new fighter and have it in production within three years. He decided that the best course of action was to concentrate on the prototype Spitfire design to meet any developments in Luftwaffe fighters and bombers.

By the end of the war, the Spitfire was a vastly different fighter from the prototype that Mitchell had known. Since his death, the aircraft had doubled its weight and engine power, had vastly increased its speed, and its armaments were a deadly combination of machine guns and cannons that the German pilots feared. In addition, the naval version of the Spitfire, the Seafire, was popular with naval pilots operating from aircraft carriers and naval shore bases. I am privileged to have met Capt. Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown who shares his memories and close association with Smith during the development of the Seafire, and also agreed to write the foreword to this book.

Smith was later involved in the designs of other Supermarine aircraft, including the Spiteful and Seafang, leading into the jet age with the Attacker. This led to the Swift, which was the first swept back winged fighter in RAF service and also held the world speed record. The last aircraft designed by Smith was the Scimitar, which was the first British aircraft to carry nuclear weapons.

Historian J.D. Scott writes about Smith in his book Vickers: A History: ‘Although he had been a great admirer of Mitchell, Smith had never tried to imitate his visionary boldness, for his own talent lay in developing things which were already known to be good. If Mitchell was born to design the Spitfire, Joe Smith was born to defend and develop it.’ One of Jeffrey Quill’s last actions before he passed away in February 1996 was to ask Gerry Gingell to compile a Supermarine Spitfire memorial book, to be called The Spitfire Book, recording the names of all the members of the Supermarine Design Department responsible for the design and development of the Spitfire between 1932 and 1945, ‘otherwise all these names will fade away and be totally forgotten’.

Shortly after Smith’s death, the design staff were notified that the lease on Hursley Park was to end, and by 1958 the famous Supermarine design team was scattered to various sites, including South Marston, Hurn and Weybridge. However, a number of the long-serving senior members of the team remained in a small office in Southampton until retirement.

This book aims to tell the story of Joe Smith’s drive, boundless energy and dogged determination to develop the Spitfire to meet any threat thrown at Britain by the Luftwaffe, and of his post-war work on the jet aircraft until his death in 1956. His dedication and leadership of the design team are demonstrated through the eyes not only of those that worked closely with him, but also of post-war apprentices, who have shared some interesting and often humorous anecdotes.

I hope that my contribution in the form of this book will add to the memory of the design team as listed in The Spitfire Book, and also give credit, which is long overdue, to the leadership and dedication of Joe Smith.

Mike Roussel

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am indebted to all who gave me their support, advice and time while I researched this book, and my grateful thanks go to all who agreed to be interviewed, and also put me in contact with others who could share their experiences and involvement with Supermarine.

My sincere thanks to Capt. Eric ‘Winkle’ Brown for sharing his experiences while testing the Seafires on the aircraft carriers and writing the foreword to this book.

It has been a great privilege to meet and talk to the sons, daughters and grand-children of the senior management of the Design and Technical Departments who have now passed away. They include Barbara Harries, daughter of Joe Smith; Alan Clifton, son of Alan Clifton senior; Judy Monger, daughter of Ernest Mansbridge; David Faddy, son of Alf Faddy; Martin Davis, son of Eric John (Jack) Davis; Ann Crimble, daughter of Eric Donald (Bill) Fear; Jennie Sherborne, daughter of George Pickering; and Sarah Quill, daughter of Jeffrey Quill. My thanks also go to Rachel Faggetter, daughter of Ted Faggetter; Diana Landon, daughter of Denis Webb; Peter Marsh-Hunn, grandson of Alfred Ernest Marsh-Hunn; and Tim Labette, grandson of Charles Labette, for their permission to quote from material written by their fathers or grandfathers.

I am especially grateful to all who were interviewed and gave me permission to use some of their own material for my book. They include Lily Bartlett, Margaret Blake, Barrie Bryant, Bryan Carter, Mary Collier, Cliff Colmer, David Coombs, Norman Crimble, David Effney, Frank Fulford, Tony Kenyon, Christopher Legg, Joy Lofthouse, Jessie Mason, Gordon Monger, David Noyce, Garth Pearce, Leo Schefer, John Thomson, Fred Veal, Muriel Wanson and Murry White.

My special thanks go to Sqn Ldr A. Jones MBE, CRAeS (Ret’d), Director of Solent Sky Aviation Museum, and I am also deeply indebted to its Archive Department, led by Dave Whatley, for the encouragement and support for my research; to Alan Mansell, for his photographs of air shows and his ongoing support in the photographic archives; and to Dave Hatchard, for assisting in accessing relevant historical documents and for his original painting of Joe Smith. I would also like to thank all who have loaned me photographs and other illustrations from their collections, including Raymond Crupi and Ron Dupas. My thanks also go to Nick Forder, curator of the Air and Space gallery at the Museum of Science and Industry, Manchester, for his help with my research studies. Visits to other aviation museums, including the RAF Museum at Hendon, Tangmere Military Aviation Museum and Fantasy of Flight, Florida, have added further value to my research studies.

Barrie Bryant and Murry White have provided valuable professional advice, consistent support and encouragement for my project, and checked my work for accuracy. My sincere thanks also go to David Key for his invitation to look around Hursley Park, which brought back treasured memories for those who had worked there.

I would also like to thank all those whom I have met not in person but through our respective websites around the world, and my special thanks go to Flightglobal.com and Murdo Morrison (RBI UK) for their courtesy in allowing me to use material from the Flightglobal archives.

Finally, I am eternally grateful to my wife Kay for her constant encouragement, especially in the past months when her loving support and care have seen me through to the completion of this book.

PART I

REGINALD JOSEPH MITCHELL

(1895–1937)

INSPIRATIONAL DESIGNER

INTRODUCTION

FLYING LIKE BIRDS

Humans have always been fascinated by flight. Observing birds in flight was the stimulus for early attempts to build wing-like structures and imitate the flight of birds by jumping from towers and high places. Because most attempted to fly by beating their wings like birds, this often led to disastrous results. It was in the late fifteenth century in Italy when Leonardo da Vinci studied the flight of birds and drew the first designs for a flying machine. These flapping-wing machines are known as ornithopters, and, interestingly, designs and prototype machines are still being made and tested in flight today.

It was in the eighteenth century that the idea of lighter-than-air flight using hot air balloons, and eventually airships, was developed, and the first rigid airship to fly, on 2 July 1900 over Lake Constance, was the original Zeppelin, built with a metal frame structure. The development of airships continued; they were used for passenger flights as well as in both World Wars, and can still be seen flying today. However, in the early years there were some fatal accidents, with airships catching fire because of the use of hydrogen. The two most famous Zeppelins were the Graf Zeppelin (D-LZ127), which first flew on 18 September 1928, and then transatlantic to North America in October 1928, and the Hindenburg (D-LZ129), which in 1936 was observed on photographic missions over the Solent area as well as other parts of Great Britain.

There were experiments with heavier-than-air winged aircraft such as model gliders, and attempts at a an early hang-glider whereby German engineer Otto Lilienthal became the first man to launch himself into the air, fly for some distance and land safely. This became the inspiration for Wilbur and Orville Wright for their first powered, heavier-than-air and controlled flight at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, USA, on 17 December 1903. The challenge and excitement in building and flying winged aircraft soon caught on, and it was in 1908 that Samuel Cody, an American who took up British citizenship, was credited with the first British powered flight. A year later, Louis Blériot made the first crossing of the English Channel in a heavier-than-air machine, winning the Daily Mail £1,000 prize.

Edwin Rowland Moon, just visible in the cockpit, ready for his first powered flight with Moonbeam II in 1910. Solent Sky

In 1907, a motor racing circuit was opened at Brooklands, Weybridge, and by the following year the site had become one of the first aerodromes in Britain. The interest in aviation was such that the first air show was held from 19–27 March 1909 at Olympia in London. Furthermore, many people wanted to become aviators, and to meet that need the first aviation school was opened at Brooklands by Hilda Hewlett and Gustav Blondeau in 1910. Other flying schools were also beginning to attract potential aviators around the British Isles, but Brooklands seemed to be the centre for such establishments. These included the Sopwith Flying School in 1912, Vickers Flying School in 1913 and the Handley Page Flying School in 1914.

As a consequence, the interest in powered flight increased and resulted in some aviators making their own aircraft. Edwin Rowland Moon, who owned the family boatbuilding business of Moonbeam Engineering, based at the Wool House, Southampton, decided to build his own homemade aircraft named Moonbeam I and Moonbeam II. Moonbeam I was first tested near Calshot, but the flight consisted mainly of short hops. His first successful powered flight was from a level field at North Stoneham Farm with Moonbeam II in 1910. This is now the site of Southampton International Airport, and was the Eastleigh aerodrome that K5054 flew from on its first test flight on 5 March 1936.

It is this interest in the development of aviation that quite possibly stimulated Noel Pemberton Billing, the founder of Supermarine, to get involved in flying and the designing and building of aircraft, especially when local interest was centred on the exploits of Moon. In the First World War, Moon joined the RNAS and after the war became a flight commander in the newly formed RAF, but was sadly killed in a flying boat accident in April 1920.

The result of the early experiments and developments in flying, including gliders, hang-gliders, hot air balloons and airships, can still be seen today. There remains a great interest in learning to fly, and many flying schools and clubs are available to meet that need. The opportunities are very wide-ranging, and include training as pilots for the RAF and commercial airlines.

1

THE EARLY YEARS

Noel Pemberton Billing

Born in 1880, Noel Pemberton Billing was an adventurous young man whose exploits led him into some dangerous moments and, it seems, challenged him even more to undertake a wide range of activities including aviation and aircraft design. An inventor with a large variety of patents, a seller of steam yachts, an actor and a playwright, and with a turbulent life as a politician during the First World War, he was a very determined man and would not be held back in whatever he chose to do. In 1908, Wilbur Wright sailed from the USA, complete with aeroplane, to demonstrate to Europe what he and his brother Orville had achieved with powered flight. Billing had heard and read about the Wright brothers’ experiments with powered flight in America, and his enthusiasm for aviation drove him to experiment with his own flying machine. Billing’s first effort was to build a glider, which when launched from the roof of his home fell apart on hitting the ground. His main problem was lack of capital, but his enthusiasm led to a wealthy friend financing the construction of an experimental aeroplane. The problem was getting a suitable site for the work to begin, but not far from his home was a disused factory in the village of South Fambridge, Essex.

Not only did he work on his own experimental aircraft, he was also keen to invite other aircraft designers whom he had met at the March 1909 air show at Olympia to build their prototype machines at his newly acquired site. He also founded a monthly magazine, Aerocraft, for which he became writer and editor, mainly to inform others interested in aviation on the progress of the ongoing experimental work and also to promote his aerodrome.

On 25 July 1909, the same year that Billing was trying to get his experimental work off the ground at his aerodrome, Louis Blériot created further interest in aviation by being the first person to cross the English Channel, from Calais to near Dover Castle, in his Blériot XI monoplane. This caused Billing to have some hope that other aviators would be interested in building their own aircraft at his aerodrome, but a series of mishaps and problems with drainage on the site, which was reclaimed marshland, led aviators to look for more suitable sites, which was not good news for Billing.

Also in 1909, Pemberton Billing had built three prototype aircraft of his own. The first was an open-cockpit pusher monoplane. He claimed his first flight as successful, but it was no more than a few short hops off the ground before it crashed in pieces. His second attempt ended similarly, despite having a more powerful engine. Billing was injured and spent a month in hospital. His third aircraft, an improved version with another new engine, was never flown because it had to be sold to settle debts, and so Billing’s Fambridge venture came to an end.

After attempting other ventures, he became involved in selling steam yachts from 1911 to 1913. This was at a time when a young Hubert Scott-Paine had joined him as his assistant and was living with Billing and his wife on board a three-masted schooner named Utopia berthed on the River Itchen, Southampton.

The Foundation of Pemberton-Billing Ltd

It was in April 1913 that the first Schneider Trophy competition took place at Monaco, and possibly spurred on by the publicity of this event, Billing made a £500 wager with another aviation pioneer, Frederick Handley Page, that he would gain his Royal Aero Club’s Aviators Certificate within 24 hours. In fact he did even better, achieving the certificate at the Vickers School of Flying at Brooklands early in the morning of 17 September 1913, even before having breakfast.

The wager of £500 came in useful, allowing Billing to purchase a disused coal wharf alongside the Woolston ferry on the River Itchen in Southampton as a site for a factory to design and manufacture marine aircraft. The overall aim was to build ‘boats’ that flew over the sea rather than those that sail on it. Interestingly, the telegraphic address chosen was ‘Supermarine’, indicating a craft that was above the sea, rather than a ‘submarine’ which was below it, and so Supermarine was born.

The first Pemberton-Billing Ltd aircraft was the biplane P.B.1. It was a flying boat and was exhibited at the Olympia Air Show in March 1914, where it was inspected by King George V. It was at this exhibition that the Germans first became interested in the P.B.1 design. The aircraft had a hull built of spruce and was powered by a 50hp Gnome engine driving a three-blade tractor air-screw mounted in the gap between the wings of the biplane.

Flying boat P.B.1 at the Olympia Air Show in 1914. Solent Sky

One of the earlier designs was for a flying boat advertised as the ‘Supermarine Flying Lifeboat’. This was the P.B.7, designed with its hull constructed as a motorboat, including a cabin for the pilot and passengers, with the wings, engine and tail section at the rear, which could be detached if the aircraft ditched in the sea. The pilot and passengers would then be able either to use the motorboat to make for safety or wait until rescued. The Germans had placed orders for the P.B.7, but following delays to the construction, the First World War had started so the German orders were cancelled. In the end, the P.B.7 was never flown, although plans had been made for initial water trials.

Pemberton-Billing Ltd in the First World War

In June 1914, Pemberton-Billing was formed as a limited company with a share capital of £20,000 put up by Noel Pemberton Billing and Alfred de Broughton, who became the directors of the company. The First World War began on 28 July 1914 and Pemberton-Billing built its first land plane, a single-seat scout biplane, just over a week later. This was the P.B.9, which was powered by a 50hp Gnome engine at a speed of 78mph (152.52km/h) and climbed at 500ft (152.4m) per minute. It became known as the ‘seven-day bus’ because it was reputed to have been designed and built in seven days. It had not been decided to build the P.B.9 scout until a Monday morning, when Carol Vasilesco, the draughtsman, started on the design. Construction of the aircraft commenced on the Tuesday and by the following Tuesday, 11 August 1914, the P.B.9 was built and ready to be flight-tested. Its first flight was made at Netley Common, near Southampton, in the presence of Hubert Scott-Paine; Victor Mahl, Sopwith’s chief mechanic, who was loaned by Tommy Sopwith to make the first flight; Vasilesco, a Romanian immigrant draughtsman working for Supermarine; and test pilot Howard Pixton. The first test was for taxiing, but Mahl went too close to a fence and damaged a lower wing. A repair was completed in a few hours by workmen from the factory, and Mahl then took the P.B.9 into the air for a successful first flight. Vasilesco sadly died at the age of 19 of heart failure on Christmas Eve 1914. Later another young man was to replace him at Supermarine; his name was Reginald Joseph Mitchell.

The P.B.9 went to Brooklands where it was tested by John Alcock for just two flights. However, he was not happy to continue flying the aircraft and it was later transferred to serve as a trainer at Hendon until taken out of service. John Alcock later became famous when, along with Arthur Whitten Brown, he was the first to fly non-stop across the Atlantic in June 1919.

The work at Supermarine during the First World War concentrated on the repair and maintenance of aircraft from the battlefields of France, as well as building under licence Norman Thompson RNAS NT2B flying boats for the Admiralty. The company was also subcontracted to build the Short 38 trainer and experimental biplanes as well as the Short 184, a patrol seaplane and torpedo bomber carrying two crewmen.

Billing decided to volunteer for the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR) and from October 1914 was given the rank of sub-lieutenant. This was to be a temporary commission as he was chosen mainly for the planning and execution of the attack on the Zeppelin airship factory at Friedrichshafen on Lake Constance because of his organisational ability. During the time that Billing was away from the factory serving in the Royal Navy the works was managed by Scott-Paine. At the time, there was little work coming in, but Scott-Paine managed to get some work from Sopwith who had a shed nearby. The work increased when the factory started to build aircraft under licence and repair damaged aircraft, and trade really started to build up when the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough began to use the Woolston works.

In 1915, the P.B.23E ‘Push Proj’ (Pusher Projectile) was designed and built at Supermarine. The pusher configuration has the propeller facing in a rearward direction, making it look like the aircraft is being ‘pushed’ through the air, as opposed to the tractor configuration whereby an aircraft with a propeller in the front is ‘pulled’ through the air. At first the Push Proj had straight wings, but these were later changed to swept back wings. This pusher single-seat scout biplane had a 100hp Gnome Monosoupape engine powering the aircraft at 98mph (157.71km/h) and was armed with a single .303 (7.7mm) Lewis machine gun. The forerunner of the P.B.25 single-seat scout which came into service for the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) for the rest of the war, it was difficult to fly, especially on take-off and landing, and its performance was not the most successful.

Billing was given leave from the RNAS in 1915 to concentrate on designing aircraft for the war effort, and especially aircraft to target the German Zeppelin threat. In the First World War, the early fighters had little experience of night fighting, but when the Zeppelins started their bombing missions at night it was down to the early form of night fighter to attack them. They started using incendiary flares that could be dropped over the airships, but the flares would leave a clear trail when dropped and this could aid the observation of the direction of the attacks on the Zeppelins. However, two quadruplane prototypes, the P.B.29E and the Supermarine Nighthawk, were specifically designed to attack the German Zeppelins.

The P.B.9 was the first land plane built by Pemberton-Billing Ltd. Solent Sky

The P.B.29E of 1915 was a quadruple wing, twin-engine night fighter aircraft in which the fuselage was attached to the second wing, with a gunner’s nacelle between the third and fourth wings. The aircraft had two 90hp Austro-Daimler engines powering two airscrews, but flew at a slow speed. It had two flight crew and a gunner with a single .303in (7.7mm) machine gun seated in the fuselage section attached to the second wing. The test programme lasted only for the winter of 1915/16, but the development continued with a new Zeppelin killer, the Nighthawk.

The Nighthawk (P.B.31E) flew in early 1917 and was powered by two 100hp Anzani 9-cylinder radial engines powering two airscrews at 75mph (120.7km/h), although in tests it did not reach this speed. However, the armaments were increased from the P.B.29E to include a 1½-pounder Davis gun mounted to fire forward, and two Lewis .303in (7.7mm) machine guns, and incendiary flares that could be dropped on Zeppelins. The aircraft was able to remain in extended flight for up to 18 hours, but there were some added crew comforts for these long hours of flight as it was equipped with a heated and enclosed cockpit with a bunk for an off-duty crew member. There was also a trainable searchlight in the nose of the aircraft to aid the pilots in finding and destroying Zeppelins in the air at night. Two Nighthawks were constructed, but the prototype did not come up to expectations and was eventually scrapped.

Supermarine Nighthawk P.B.31E quadruplane. Solent Sky

Future Senior Managers

A number of young apprentices working in well-known British engineering companies were forging their future careers in aviation just before the start of the First World War. One name that was to feature in the senior management of Supermarine after the conflict was James Bird who was educated at Marlborough and had an engineering background. After serving an apprenticeship at the Elswick shipyard of Sir W.G. Armstrong, Whitworth & Co., he became a qualified naval architect and later bought and ran a small shipyard in Wivenhoe, Essex. Bird became interested in aviation and built himself an aeroplane in early 1914, obtaining his pilot’s licence. At first he joined the RNVR, but when the First World War broke out he transferred to the RNAS.

Reginald Joseph Mitchell became deeply interested in the development of aviation while a student at Hanley High School. It was then that he started to design, build and fly his own model aircraft. So interested was he in his hobby, his school friends commented that ‘he was mad about aeroplanes’. On leaving school in 1911, he joined join Kerr, Stuart & Co., a locomotive engineering firm in Stoke-on-Trent, as an apprentice. After starting in the engine workshop he was transferred to the drawing office where his interest and talent for design work began to be recognised. Mitchell’s drive to succeed in this area led him to attend evening classes to increase his knowledge and skills in technical drawing, mechanics and higher mathematics. At the time he was an engineering apprentice, major events were beginning to bring the development of aircraft and aviation to the fore. Among these events were the Schneider Trophy races, which were to become a great influence on his future career in aviation.

While Mitchell was still an apprentice at Kerr, Stuart & Co., his future chief draughtsman and colleague Joseph Smith had left Birmingham Municipal Technical School in 1914 to start an apprenticeship at Herbert Austin’s motor works at Longbridge. This was at the beginning of the First World War and Smith was just old enough to serve in RNVR. There is a story that, in 1917, he was involved in taking a naval motor launch through French rivers and canals all the way to the Mediterranean, finishing up in Malta at the end of the war. Eight motor launches had left Portsmouth for the Mediterranean before eventually arriving in Marseille, some with damaged propellers after striking underwater obstructions. Two of the motor launches went on to Gibraltar for repairs, four sailed to Italian ports and two sailed to Malta, Smith being a crew member of one of them.

After the war, Smith returned to complete his engineering apprenticeship. Austin’s had by this time moved into aircraft production and Smith was transferred to the aircraft section where he became a junior draughtsman in their aeroplane drawing office. It was an interesting and exciting period to be part of the development of aviation. In 1919, the Austin Whippet, a single-seat biplane, was being designed by the company’s chief aircraft designer, J.D. Kenworthy.

When Austin’s withdrew from aircraft production, Smith was keen to continue in the field of aviation design so he left to join Mitchell at the Supermarine Aviation Works in Southampton in 1921. This was a case of being ‘in the right place at the right time’ because Mitchell was then looking to build a team of young engineers for his future design and technical team. He knew exactly what kind of man he was looking for, and Smith was one of the first to be appointed. Little was Smith to know at the time that he would eventually become the chief designer and leader of the design team at Supermarine.

Another young man who undertook his engineering apprenticeship about the same time as Mitchell and Smith was Alf Faddy. He grew up in Wallsend and gained a scholarship to the Royal Grammar School in Newcastle upon Tyne. However, when his father became unemployed and shortly afterwards passed away, he had to leave school and go to work to support his mother, younger brother and sister, becoming an apprentice at Parsons of Newcastle. The company were famed for their development of the steam turbine and for their introduction of the launch Turbinia that reached a speed in excess of 34 knots when it was shown at Queen Victoria’s Jubilee review in 1896. At that time, it was the practice for apprentices to be sacked on completing their apprenticeship. This was so that they moved to other engineering firms to gain a wider experience and develop their skills further, before perhaps moving back to the firm where they had undertaken their original apprenticeship. However, this was not the case with Alf Faddy as he was retained by Parsons, who offered him a job as a chargehand.

Joseph Smith joined the RNVR in 1914, serving on the motor launches. Barbara Harries

Alf Faddy, similarly to Smith, also served in France during the First World War after joining the RNAS. He was fortunate when returning from France to be stationed at RNAS Felixstowe where he was able to work alongside Lt-Cdr John Cyril Porte on the Felixstowe flying boats. Felixstowe was an experimental station for the designing and building of flying boats that had been set up at the start of the war under Porte’s command.

John Cyril Porte

Lt-Cdr John Cyril Porte initially joined the Royal Navy submarine service, but after contracting tuberculosis was discharged from the Royal Navy in 1911. This did not deter him and he went on to learn to fly, taking part in air races. His interest in flying boats developed when he met American Glenn Curtiss, also an experienced air race competitor, in Brighton. Both men joined together with the aim of designing and building an aircraft that would fly the North Atlantic. This design work was carried out in the USA and the result was the ‘America’ flying boat. However, with the start of the First World War the plan was dropped. From his work with Curtiss, Porte first equipped the station at Felixstowe with American Curtiss flying boats, but when they were used on patrol in the North Sea it soon became apparent that their hulls were not suited to the rough sea conditions they encountered. There was an urgent need for Porte to redesign and replace the old hulls, but by that time the experimental designs and development of the Felixstowe flying boats gradually took over.

Some of the Felixstowe flying boat hulls were constructed at the May, Harden & May sheds on Shore Road, Hythe, Hampshire, which had been built by the Admiralty for flying boat construction in the First World War. May, Harden & May was a subsidiary of AIRCO (the Aircraft Manufacturing Co.) based in Hendon. The Felixstowe flying boats were used to fly on patrols from their base at RNAS Felixstowe, looking for the German fleet and U-boats. They were also used to spot and attack Zeppelins, which had become more prominent from their bombing missions on British towns and cities.

When the RAF was formed in 1918, the base was renamed the Seaplane Experimental Station, but was closed in June 1919, the same year that Porte died from tuberculosis. The site of the Seaplane Experimental Station was eventually taken over by the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment (MAEE) in 1924. This was where the RAF High Speed Flight was formed for the Schneider Trophy race in 1927. However, after the 1927 race, which was held in Venice, the government disbanded the High Speed Flight, partly because of cost but also because there were no serving officers taking part in the races. The High Speed Flight had been formed initially because other competing countries were using military pilots, which was felt to be a disadvantage to the British entries for the Schneider Trophy. The High Speed Flight was later re-formed and was then based at Calshot for the 1929 and 1931 Schneider Trophy races, both won by Britain, which then retained the Schneider Trophy. The MAEE Felixstowe was visited by Mitchell regularly in connection with his design and production of flying boats. He was often flown from Southampton to Felixstowe by George Pickering, who was later to become a test pilot for Supermarine.

2

SUPERMARINE AVIATION WORKS LTD

Billing decided to become a Member of Parliament in 1916 and sold his shares in Pemberton-Billing Ltd to Hubert Scott-Paine, who promptly renamed the company Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd. Billing’s decision to become an MP followed his many contributions and reviews in newspapers on aviation development in which he also set out his views on the part aviation could play in warfare.

Admiralty Air Department

The government had assumed control of the Supermarine works to construct Admiralty designs, and also for repairs. The twin-float Navyplane and A.D. (Air Department) Flying Boat, designed by the Admiralty, were constructed at the works.

Seaplanes differ from amphibians in that they can land only on water whereas amphibians can land both on water and a runway. Seaplanes can be either a flying boat or a floatplane. A flying boat has a single hull and floats on water, and the floatplane is an aircraft that has streamlined floats instead of wheels.

The Navyplane was a twin-float pusher seaplane designed by Harold Bolas for the Admiralty Air Department in 1916 to undertake the role of a reconnaissance aircraft. Flight tests from August 1916 revealed that the aircraft was underpowered and its original engine, a Smith radial, was replaced by a Bentley BR1 rotary engine powering a pusher propeller. Lt-Cdr John Seddon then conducted the trials with the new engine, but the performance was still not good and only the 9065 was built.

Also in 1916, the A.D. Flying Boat, powered by a 200hp Hispano-Suiza engine driving a single pusher propeller at 100mph (160.93km/h), was designed by Flt Lt Linton Hope for the Admiralty Air Department. It was a two-seat patrol biplane flying boat with a biplane tail and twin rudders. Its role was to support Royal Navy warships at sea, so it had fold-back wings to enable easy stowage on a ship. The aircraft, although essentially a flying boat, had wheels that could be used to take off from land or a ship. Once airborne, the wheels could be jettisoned. It had a crew of two, a pilot and an observer who would be responsible for firing the single .303in (7.7mm) Lewis machine gun, and wireless for communication with the ground. Two prototypes were built, the test programme proving that the prototypes had handling problems, both on the water and in the air. However, the problems were successfully remedied and orders for production placed.

Pemberton-Billing Admiralty Navyplane. Built in 1916, it carried two crew, a pilot and observer, and was armed with one Lewis machine gun and carried a torpedo. Only the 9065 was built. Solent Sky

Reginald Joseph Mitchell CBE, AMICE, FRAeS

That same year, a young man who was eventually to become a world-famous aircraft designer was looking for his first job. That young man was R.J. Mitchell. Having just completed his apprenticeship, he had seen an advertisement for a job as an assistant to Hubert Scott-Paine at Supermarine Aviation Works. He decided to apply, was successful in obtaining the post, and was invited to join Supermarine. Thus began his journey to becoming a famous aircraft designer.

Mitchell got to work immediately and was available to assist Bolas in the design of the Navyplane, which made its maiden flight in August 1916. During his twenty-year career with Supermarine, Mitchell was to continue the company’s tradition of manufacturing flying boats before culminating in the design of the prototype Spitfire fighter aircraft. He was also to work with the chief designer, F.J. Hargreaves, on the Supermarine Baby. As a new member of the design team, Mitchell was given the task of producing some of the drawings for the aircraft.

The Supermarine Baby (N1B) was a single-engine pusher biplane flying boat with a wooden hull designed by Hargreaves to Admiralty Air Department requirements in 1917. It was powered by a 200hp Hispano-Suiza engine at a speed of 116mph (186.68km/h). The pilot’s cockpit was situated in the nose of the aircraft. Although its tests proved encouraging, the Royal Navy was looking for a land plane design that could take off from a ship, and only one prototype eventually flew before the project was abandoned in 1918. However, the design work on this aircraft was not lost as it became the forerunner of the Sea King fighter and the Sea Lion racing aircraft.

By 1918, Mitchell had been promoted to the post of assistant to Mr Leach, the works manager, and the same year Mitchell married Florence Dayson, headmistress of Dresden Infants’ School, Stoke-on-Trent, whom he had been courting before his move to Southampton. They had one son, Gordon, who was born in 1920.

Mitchell made his mark early in his career at Supermarine and was destined to become chief designer in 1919, at the age of 24, when Hargreaves left. In 1920, he was appointed chief engineer, and was promoted to become technical director just seven years later.

N13 Section

Cdr James Bird’s service records show that in about 1915 he was posted to Southampton to take charge of the N13 Section of AIRCO as Admiralty overseer of aircraft and boat builders on Southampton Water, including Supermarine. The N13 Section later included the subsidiary May, Harden & May which occupied the old Admiralty sheds in Hythe for building the Felixstowe flying boats. It was the yacht-building yards that became part of the N13 Section because they had the skilled workmen creating wooden craft and these skills were transferred to manufacturing the wooden hulls of the flying boats. When Bird’s demobilisation came along in 1918, it was on the strong recommendation of the Director of Inland Ports and Waterways to the Admiralty that he should leave with the rank of squadron commander, on condition that he continued to serve N13 Section as before but as a civilian. As a keen supporter of the flying boat, Bird then joined Scott-Paine at Supermarine Aviation Works.

Another future member of the Supermarine management team was Alfred Ernest Marsh-Hunn. In 1911, he started an apprenticeship at a Whitworth shipyard and qualified as an associate member of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1916. His grandson, Peter Marsh-Hunn, remembers his mother saying that her father originally came from Woolwich, and when aged about 17 his interest in aviation led him to invent a method for mending the fabric wings on aircraft. As he was too young to patent it himself, a businessman from London, Mr Grey, patented it for him on the understanding that the profits would be shared. These monies were paid to him until he retired.

Because of the First World War, Marsh-Hunn was recruited into a temporary Civil Service post as an aircraft inspector in N13 Section of AIRCO. At the end of the war, when the N13 Section temporary staff were being demobilised, Marsh-Hunn consulted with Bird on his future career and Bird persuaded him to take a business management course with a view to working under him in the future. In July 1919, after completing the course, Marsh-Hunn was appointed as business manager to Supermarine Aviation Works at the time when Supermarine were seeking commercial work to replace the Admiralty contracts.

When Bird purchased the company from Scott-Paine in 1923, Marsh-Hunn’s position in the firm was strengthened, as it was when Vickers purchased Supermarine, due to the good relationship he had developed with Head Office. Along with Joe Smith he was later appointed a special director to report to the Vickers board on finance and contracts. When in the 1950s Supermarine were beginning their transfer to South Marston, Marsh-Hunn at the age of 60 decided to retire and concentrate on his private business interests.

Building the Supermarine Design Team

Mitchell had already been ‘hooked’ into aviation by the time he was appointed assistant to Scott-Paine in 1916 and was working with design staff, some of whom had started in 1913, probably with Pemberton-Billing Ltd, and then transferred to Supermarine Aviation Works Ltd. They included Frank Holroyd, who later became assistant chief designer to Mitchell; W.T. Elliott, who was to become the works manager; Arthur Shirvall, who joined as an apprentice in 1918, specialised in hull design and later became head of new projects; Cecil Gedge, who started in 1919; and George Kettlewell, who started in 1920, the latter two both eventually becoming senior draughtsman.

The management of the company was in the hands of Scott-Paine from 1916, with Bird joining in 1918, and his ‘lifelong colleague’ Charles G. Grey appointed as company secretary in 1919. Joe Smith joined as senior draughtsman in early 1921, and soon proved himself by his drive, energy and technical skills which led Mitchell to promote him to chief draughtsman in 1926. Harry Tremelling followed in 1922 as senior draughtsman, and also taught drawing skills part-time at evening classes. Jack Rice also started as an apprentice the same year and was later to become head of electrical systems.

Until the early 1920s, the Royal Aircraft Establishment (RAE) at Farnborough had responsibility for airworthiness. Firms were required to provide the RAE with copies of their drawings, plus evidence from calculations and tests already performed. Most detail design relied on the eye and experience of the draughtsman; Mitchell undertook the calculations necessary to determine principal airframe dimensions. His growing workload led to an advertisement for a technical assistant to help him with calculations, and he also wanted to attract a young team of keen, interested engineers to become part of the Supermarine design team.

Alan Clifton had graduated in 1922 with a BSc in aeronautical engineering, and his first job was at a patent agent’s office for a very short time. In 1923, he saw an advertisement for a technical assistant and was very keen to get the job, so rode his motorbike to Supermarine at Woolston. In his lecture to the Southampton branch of the Royal Aeronautical Society in 1976, he talked about his appointment: ‘Mitchell did all the calculations relating to performance and stress, and in 1923 he employed me as his technical assistant to carry out such work – a great stroke of luck for me.’ This was a good move for Clifton, especially at a time when Mitchell was choosing and building up his future design team and the Schneider Trophy racing seaplanes were being developed. Clifton was often referred to by the team as ‘Cliffy’, his son, also named Alan, being referred to as ‘Little Alan’ or ‘Young Alan’. Where there is a need in this book to distinguish between Clifton senior and junior the reference will be ‘Cliffy’ or ‘Young Alan’.

From about 1923, university graduates were recruited to undertake calculations to do with structural strength and aerodynamics; then, in 1924, came the Air Ministry ‘Approved Firms Scheme’ which transferred certain airworthiness responsibilities from the RAE at Farnborough to airframe constructors. These graduates formed the nucleus of the technical office, as distinct from the drawing office. Later, all were classified as ‘stressmen’, a term borrowed from marine engineering. Gradually young recruits from school became junior technical assistants, who after attending night school for a number of years became recognised members of the technical office. Early tasks for a junior were the keeping of weight records, weighing parts, measuring the weight and centre of gravity position of the complete aircraft, and preparing loading instructions for test flights.

In 1924, Ernie Mansbridge BSc joined the Mitchell design team. His daughter, Judy Monger, refers to her father’s studies at the East London College, London University, where he did two courses in one under the tutorship of Professor N.A.V. Piercy, who is credited as writing many of the books used by aeronautical students. Mansbridge undertook the aeronautical course and also the civil and mechanical engineering course, which gave him an extra day a week to study aerodynamics and aeroplane design. When Mansbridge finished at university, Professor Piercy wrote this reference on 12 September 1924 for him:

He proved a very satisfactory and diligent student and is confidently recommended for a drawing office post in an aeronautical firm. He has first-hand acquaintance and experience of wind channel testing and is competent to carry out testing, performance and strength calculations. I have no doubt he will prove a very useful man.

Mansbridge received a letter dated 17 September offering him a job at £2 10s for the first year, signed by Mitchell, and one dated 22 September adding: ‘ … note that you consider our offer satisfactory; please could you start as soon as possible?’ He started on 25 September 1924, straight from university.

At the time of joining Supermarine in 1924 there was a design team of twenty-four, Mansbridge becoming the third member of the Supermarine technical office. By 1929, he was responsible directly to Mitchell for aerodynamics, performance, weights and flight-testing.

Eric Lovell-Cooper also joined Supermarine in 1924. He had started his training at the Norwich aircraft firm of Boulton & Paul in 1918, and having proved himself as a promising aircraft engineer was advised to try for a job at Supermarine ‘as they had a very bright designer working there’. This designer was, of course, Mitchell. Others who joined in 1924 were Reginald Caunter; Oliver Simmonds, an aerodynamics specialist who also taught the subject part-time; Oscar Sommer, who specialised in airscrew design and structural testing; Wilfred Hennessy BSc; and Harold Holmes BSc, both of whom worked in the Stresses Department. Miss J. Leach joined in 1925 as a tracer and was an assistant to the chief tracer Miss Farley, later taking over the position.

The team was getting larger, with William Conley joining in 1926 and Harold C. Smith in 1928. The same year, Simmonds left Supermarine to set up his own aircraft factory at the Government Rolling Mills at Weston, which he named Simmonds Aircraft Ltd. His first prototype was the Spartan biplane, christened by the Mayoress of Southampton on 31 December 1928. The company gained further financial support from an investment company and changed its name to Spartan Aircraft Ltd in 1930, moving to the Isle of Wight. However, it went out of business in 1935 and was merged with Saunders-Roe.

The Supermarine Metallurgical Department

Arthur Black was recruited by Mitchell as a metallurgist to develop a metallurgical department in 1926. He later became head of research and systems testing. In 1928, he was joined by Harry (‘Griff’) Griffiths as his laboratory assistant. After his scoutmaster informed him that there was a vacancy in the Supermarine laboratories, Griffiths had been keen to find out more about the job, and the next morning he travelled over to the Supermarine works on the Woolston floating bridge where he met the chief metallurgist. In his book Testing Times: Memoirs of a Spitfire Boffin, Griffiths describes his impression of Black’s office:

His office was most interesting – half of it was taken up with bits and pieces of aircraft; panels, tanks and what looked like the beginnings of a pair of skis. By the desk was a discarded fuel tank which served as a wastepaper bin. On the bench behind was a laboratory balance, microscope and other bits of apparatus.

With an interest in chemistry, he was fortunate to see in the chemical laboratory next door a labelled bottle showing the formula for nitric acid, because that was one of the questions he was asked by Black. Griffiths got the job and was asked to start work the following Monday morning at nine o’clock, and as part of his apprenticeship was required to attend night school for five years.

In his book, Griffiths refers to works laboratories being regarded as a supplier of anything that was remotely connected with chemicals and also acting as a general test facility. He mentions checking the accuracy of all the instruments used, including pressure gauges, altimeters and air speed indicators. In the early days, improvisation was the key to the success of some of the test situations and Griffiths mentions Sommer, who was in structural testing, as being a past master in improvisation. When a problem arose whereby the team had to find the best arrangement for the landing wheels of the Walrus amphibian flying boat, Griffiths searched in his attic at home and found some Meccano parts which they improvised to make a trolley to test the best stability for the wheels.

At the time when drop tanks were being developed to extend the range of the Spitfire, the pilots reported that they had difficulty in releasing the tanks. To gain an idea of the problem, Black and Griffiths flew alongside a Spitfire in the Supermarine ‘Dumbo’ and filmed the dropping of the tank. The analysis of the film revealed the tank sliding back until it hit the tailwheel before dropping away. As they had no access to a wind tunnel, the team used cardboard boxes and an industrial blower to undertake a test, and a solution to the problem was identified: ‘Finally two hooks were fitted just aft of the tank to limit the distance over which it could slide, and in our cardboard “wind tunnel” the hooks were drawing pins!’

Premium Apprenticeships and Trade Apprenticeships

It was possible in the 1920s and early 1930s for employers to offer two types of apprenticeships: premium apprenticeships and trade apprenticeships. With the premium apprenticeships the parents paid £100 per year during the length of the apprenticeship, which could be up to five years. Most premium apprentices had stayed on at school until the age of 16 before taking up their apprenticeships.

Murry White believes that by 1930 there was also another grade of apprentices who did not pay a premium, namely the design apprentices: ‘I think Roger Dickson was one followed by George Nicholas, myself, Doug Scard and Barrie Bryant.’ The design apprentices usually joined the technical office after working as office boys and runners for Clifton (Cliffy) and Mitchell, and would attend Southampton University either one or two days per week. However, Murry White wanted to gain practical experience in the factory working in the different departments, but by doing so it took him six years to complete his courses.

The trade apprentices left school at the age of 14 and then undertook part-time studies at a technical college. It was the trade apprenticeships which most draughtsmen took up; some moved around to other companies for a time but many returned to their original company as a section leader. H.C. (Harold) Smith was a trade apprentice who became a foreman and progressed to structural engineer and by 1945 was a section leader in the technical office in charge of stresses. It was the premium apprentices that had the opportunity to take up positions in the more senior management positions of the company.