Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

A pioneering aviator and advocate of women's equality, Amelia Earhart was, and continues to be, an inspiration to people the world over. Her fierce determination to break records and push the boundaries of aviation led her to become the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic Ocean in 1932, as well as the first person (man or woman) to fly solo the trans-Pacific flight from Hawaii to California in 1935. Not content to leave it at that, Amelia set her sights on becoming the first woman to circumnavigate the world, but her brave attempt was cut short when she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, vanished over the Pacific Ocean on the final stretch of the challenge in 1937. Eighty years on and our fascination with Amelia Earhart continues. Here, Mike Roussel charts her life and experiences, exploring the investigations and theories surrounding her mysterious disappearance and revealing the naturally courageous spirit that made her one of the most daring of twentieth-century women.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 202

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Cover illustration courtesy of Mary S. Lovell

First published in 2017

The History Press The Mill, Brimscombe Port Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QGwww.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2017

All rights reserved © Mike Roussel, 2017

The right of Mike Roussel to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7509 8331 0

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1 Tomboy Years

‘Being a Mechanical Person’

Learning to Fly and Early Successes

2 The Challenge of Flying the Atlantic

Flying the Atlantic for the First Time

3 Racing and Autogiro Escapades

Flying the Atlantic Solo

4 More Record-Breaking Flights

5 Around-the-World Attempt One

Oakland to Honolulu

6 Around-the-World Attempt Two

Oakland to Natal

Central Africa, Indian Subcontinent and Asia Leg

Final Leg Before Disappearing

7 The Search

Theories and Investigation into the Mystery

Amelia Earhart’s Legacy

World Flights

Epilogue

Glossary

Bibliography

FOREWORD

BY JOY LOFTHOUSE ATA PILOT 1943–45

As a young teenager, I marvelled at the flying achievements of Amelia Earhart and our own Amy Johnson. Of course, there was no television in the 1930s, but they often featured on the newsreels at cinemas.

At that time I could never have imagined that I myself would be flying during the Second World War. I was not a pre-war flier, but I was trained to fly as an Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) ab initio pilot, so I was not in the ATA when the first American girls were brought over by Jacqueline Cochran. When America came into the war, most of these girls returned to serve in the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). Of the few who stayed, I knew both Roberta Leveux and Ann Wood.

Despite the thrill of flying service aircraft for two years, the achievement of women such as Amelia Earhart, who flew such long distances, never ceased to enthral me, and this book is a tribute to a brave and bold woman who was ahead of her time in her daring and who inspired young women all over the world to ‘have a go’.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

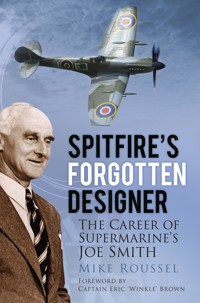

My special thanks go to Joy Lofthouse for writing the foreword to this book. Joy’s story can be read in Spitfire’s Forgotten Designer: The Career of Supermarine’s Joe Smith, published by The History Press.

I am indebted to all who gave me their support, advice and their time while I was researching this book, and also those who have loaned me photographs and other illustrations from their collections. These include Ron Dupas’s 1000aircraftphotos.com, which includes photographs from the Jim Brink and Ed Garber Collection and David Horn Collection. Other photographs come from Bill Larkins, Jim Geldart, Grace McGuire, Mike Pocock, National Archives and Ames Historical Society Collection.

I am deeply indebted to Mary S. Lovell for the use of her research papers and photographs gathered in the process of writing her book, The Sound of Wings.

My grateful thanks go to Amy Rigg and her team at The History Press for their valuable professional advice and support through to the publication of my book.

I would also like to thank all I have contacted through their respective websites around the world for their help and support.

My special thanks go, as always, to my wife, Kay, for her constant support and encouragement of my work, and for keeping me refreshed with sandwiches and cups of coffee.

Whilst I have consistently aimed for accuracy and have contacted copyright owners where applicable, I can only apologise and stress that should there be any omission, please contact me through the publishers and it will be rectified in future editions.

INTRODUCTION

Amelia Earhart was suddenly catapulted into fame in 1928 when she became the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. She made the trip in the Friendship with Wilmer ‘Bill’ Shultz, the pilot, and Louis Gordon, the flight engineer. Amelia, a social worker at the time, had already learned to fly independently, and whenever she could manage it, she would go to the local airfield to increase her flying hours. The prospect of the Atlantic trip was an experience that she did not want to miss and her understanding manager at Denison House in Boston, Massachusetts, gave her time off so she could make the flight. Nonetheless, Amelia loved her work as a social worker teaching English to immigrant children, and planned to return to the role after the flight.

After the trip Amelia found herself at the centre of a media firestorm, but she was uncomfortable with the attention, feeling the celebrity status that was heaped upon her was misplaced because she did not actually do any of the flying herself; she was merely a passenger and commented that she felt ‘like a sack of potatoes’. Despite trying to share the praise with the pilot and engineer, she was unsuccessful and they tended to be left in the background, at least in the UK. However, when the three aviators arrived back in the USA all this changed and the three of them were involved in the welcoming ticker tape parades. After this life-changing experience, Amelia vowed that she wanted to be the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic, just as Charles Lindbergh had been the first man to do so in 1927.

Amelia enjoyed horse riding and rode regularly at Rye when she was at home. (Courtesy of Mary S. Lovell)

Standing in front of the PCA-2 Pitcairn autogiro. (Courtesy of Mary S. Lovell)

Over the next few years Amelia was to become the best-known aviatrix in America, but much of the success in publicising her name must be attributed to the publisher George Putnam, who later became her husband. Her reputation became one of great daring and of a fierce determination to break records and push new boundaries in aviation. She was well known for her charismatic personality and outspoken nature, but the media quickly picked up on the remarkable coincidence that she physically resembled Charles Lindbergh. Charles was nicknamed ‘Lucky Lindy’, so they referred to Amelia as ‘Lady Lindy’.

Amelia was born into the late Victorian era and would have been expected to settle into the traditional role of a young lady, but she would never have been content with that. She enjoyed spending her childhood years as a tomboy, along with her sister Muriel, and decided at an early age to do something about the male-dominated workplace, as she believed that women should have equal rights to men. As a child Amelia led a very peripatetic life, moving around with her father’s work and attending many different schools. She was an intelligent, hard-working scholar and did not waste her time, something which did little to endear her to those of her peers who just wanted to fool around.

While at finishing school, she went to stay with her sister in Canada for the Christmas vacation, but after seeing the wounded Canadian military from the First World War she decided to stay and become a voluntary nurse working in the Spadina military hospital. Amelia discovered that some of the patients she nursed were pilots who had fought in the war and during her time at the hospital she got to know them quite well, sharing with them her interest in flying. When they had recovered enough they invited her to go with them to a local military airfield where she could watch the take-offs and landings. This reignited the interest that sparked after her first experience in a biplane, when her father paid for her to have a ten-minute flight with ex-army pilot Frank Hawks.

Amelia eventually took up flying lessons and bought her own plane, but was forced to take a series of jobs to help pay for it. After a time, she went to work at Denison House, and it was while working there that she was invited to take part in the Friendship flight. From that moment her flying career started to take off, with her breaking flying records, writing her first book about the Friendship flight and penning articles for magazines. She took part in lecture tours, became a career adviser to female students and even promoted her own fashion line, as well as endorsing various commercial products. Amelia’s fame spread far and wide; soon it was not only in America that she was well known, but also around the world.

On 2 July 1937, Amelia, along with her navigator, Fred Noonan, disappeared without trace while making for a landing on the tiny Howland Island in the South Pacific. There have been many theories about what may have happened, but as yet no solid evidence has been produced.

1

TOMBOY YEARS

Amelia Earhart’s story begins when her parents, Amy Otis and Edwin Earhart, met at a coming out ball. They were immediately attracted to one another, despite coming from entirely different backgrounds. Amy was born into a wealthy family, highly respected in their community, but Edwin had a less privileged upbringing. His father was a Lutheran minister and his family life was one of struggle and poverty. However, Edwin wanted to better his chances in life and worked hard to pay for his training as a lawyer at Kansas University.

Amy’s father, Judge Alfred Otis, a retired district judge who, during his retirement, held positions as president of Atchison Savings Bank and warden of the Trinity Episcopal Church, was not entirely happy with the developing relationship between his daughter and Edwin. He did not consider her suitor to have a high enough social standing, but Judge Otis’s concerns had no effect on Amy, who was deeply in love with this handsome and charming young man. Nonetheless, he was not convinced that Edwin, an inexperienced lawyer, would be able to achieve a salary sufficient to provide for his daughter’s needs, so he set him a challenge: if he could achieve a salary of at least $50 a month, which he considered would be enough to provide for his daughter, then he would agree to give her hand in marriage. Edwin was determined to meet the challenge, but it took him five years to do it, during which time he worked as a claims lawyer for a railroad company. Throughout this time Edwin and Amy remained very much in love. They eventually married on 18 October 1895 at Trinity Episcopal Church in Atchison and lived in a fully furnished house in Kansas City, where Edwin worked, provided by Amy’s parents.

Amelia’s parents, Edwin and Amy. (Courtesy of Mary S. Lovell)

Amelia Mary Earhart was born on 24 July 1897 at the home of her maternal grandparents in Atchison, Kansas. Amy had travelled there from Kansas City so that she could give birth to her baby where she had the support of her family and friends. The baby’s names were chosen from both her grandmothers – Amelia Otis and Mary Earhart. Amelia’s sister, Muriel, was born on 29 December 1899. As the sisters grew up they became very close and gave each other nicknames: ‘Millie’ for Amelia and ‘Pidge’ for Muriel.

Amelia’s grandparents’ house, where she was born. (Courtesy of Mary S. Lovell)

Amelia in her christening robe, October 1897. (Courtesy of Mary S. Lovell)

Amy did not find the deprivations of her married life easy, but was determined to do her best. However, it was soon apparent that Edwin was not good with money and found it difficult to provide for his family. This became a deep concern for Amy, who was struggling with the day-to-day needs of the family. Judge Otis also became very worried about his daughter, as it appeared that his initial misgivings might have been well founded.

Edwin wanted to prove himself and tried various plans to gain extra money. One was an invention for a signal flag holder for trains, for which he used the funds Amy had been saving to pay a tax bill, but he found that someone else had already patented a similar device. Judge Otis thought that the cost of the patent application and travel to Washington was a total waste of money.

Millie (Amelia) and Pidge (Muriel) sitting on the front porch at their Kansas City home, 1904. (Courtesy of Mary S. Lovell)

Nonetheless, Amelia spent her early years in some comfort, living with her grandparents during the winter months while studying at the same private college preparatory school that her mother had attended and returning to Kansas City for the holidays. Amelia’s childhood was happy and she had family and friends all around her. The main conflict in her life was the expectation of her grandparents that she should behave in a more ladylike fashion, as per the social standards of the day, but she was more interested in adventure.

Amelia was known to be independent, clever and daring in the adventures and games she organised for her friends. She liked all types of sport and games, including riding bicycles and playing tennis and basketball. Amelia and Muriel’s father was happy to see his daughters playing ‘boys’ games’ and readily indulged them with footballs and sleds. In those days, girls were expected to ride short sledges while sitting upright, whereas boys had longer sledges on which they would lay face down and speed down the slopes. However, it was fortunate for Amelia that one Christmas her father gave her one of the longer sledges because it saved her from a serious accident. Amelia remembered speeding down a steep slope just as a rag-and-bone man with his horse and cart started to cross her path from a side road. There was no chance that she could turn the sled in time and fortunately it went between the front and back legs of the horse. Had she been sitting up on a short sled in the traditional way for girls her head would have struck the horse’s ribs, causing her serious injury. This piece of good fortune did little to assuage the concerns of her maternal grandparents about the suitability of the girls’ outdoor activities.

Amelia’s mother was aware of the games the girls were involved in and had gym suits made up with bloomers gathered in at the knees, contrary to the conventional dresses that ‘nice girls’ were expected to wear. As a young lady, Amy had also taken part in adventurous activities and was the first woman to climb Pike’s Peak, Colorado, so she was not overly concerned that both her daughters were similarly inclined.

Edwin was keen to ensure his family enjoyed the interesting experiences the world had to offer and spent hundreds of dollars taking them to the 1904 World’s Fair in St Louis. Again, Judge Otis was not impressed, considering it to be yet another waste of money. Despite this, the girls had a wonderful time, so much so that Amelia, impressed by the roller coaster, built her own model version at her grandparents’ home after their return. Yet again, her grandparents did not approve; they thought it highly dangerous and, as soon as her mother found out about it, Amelia was told to dismantle it.

In 1905 Edwin joined the claims department of the Rock Island Railroad Line. At last, with a regular salary, he was going to be able to make life more comfortable for the family, something they sorely needed, but it would mean another move, this time to Des Moines, Iowa.

While their parents were looking for a new home, the girls were left with their grandparents until a house could be arranged, but the anticipated stay of a few weeks took much longer than expected. Therefore, their grandparents, keen to encourage their educational development, arranged for the girls to attend a small private college preparatory school. Amelia enjoyed learning and developed a keen interest in all educational subjects, especially music, reading, writing, French, sewing, and, of course, sports. Although the girls missed their parents, living in their grandparents’ home was comfortable and the couple were very pleased to have them. The girls also had two cousins who lived nearby, who they played with frequently.

In 1908 Amelia and Muriel joined their parents in Des Moines, but even while there the family still moved to four different homes. Their father travelled frequently for his work and the family often went with him. Happy summer holidays were spent at Worthington, on the shores of Lake Okabena. Edwin would take the girls fishing on the lake and Amelia played plenty of sports. She even learned to ride a 12-year-old Indian pony that belonged to some friends. Amelia said the pony ‘could be bribed by cookies to do anything’, and as there was no saddle available the sisters would ride it bareback. Amelia saw her first aeroplane at the 1908 Iowa State Fair at Des Moines. Interestingly, at the time it held no interest for her and she later commented that ‘it was a thing of rusty wire and wood’.

In 1909, Edwin was promoted again, to claims agent. He was now in charge of a department and saw his salary almost double, plus he had the opportunity to use his own private railroad car for business and private use, which afforded Amelia the opportunity to travel to different parts of the country. She did not consider that her many trips away caused any detriment to her education, saying, ‘It did not materially hinder school experience. I think possibly I gained as much from travel as from curricula.’ This was also the opinion of her father, who would encourage his family to travel with him. Amy, who had for so long been burdened with the running of the household while trying to balance the diminishing finances, found that with her husband’s promotion and increase in salary she was now in a position to employ staff to help her.

Life with their father had been far from dull and the girls had fond memories of the fun they had when he fooled around and played with them. Edwin read stories to them and would challenge them to tell him the meaning of strange words, some taken from a dictionary and some that he made up. More interestingly, he told them his own imaginary stories, mainly westerns, which Amelia said ‘went on for weeks’, with her father playing the leading role. At weekends he would join in with the girls and their friends, playing ‘Chief Indian’, with the scenes of the Indian wars re-enacted in their barn in Des Moines. One controversial thing Edwin did, which horrified Amelia’s grandparents, was to give 9-year-old Amelia a .22 rifle to clear the barn of rats. Amelia had heard stories of the plague where the rats carried the disease around and was anxious that this should not happen to her family, but her grandparents thought a rifle was far too dangerous for a child of that age to use.

Family life was happy, but this was not to continue. As time went on their father started drinking heavily. The seriousness of his drinking habits became more of a problem when he started to do it during and after work, staying out late and imbibing with his friends. He would often arrive home late, much to the disappointment of the girls, who had been waiting for him to play with them. The girls started to call their father’s alcoholism ‘Dad’s sickness’.

Edwin was warned by his employers that if he did not try to tackle his problem he would be fired. He sought medical help and was in hospital for a month, but on returning to work he started drinking again and this led to his dismissal. There was to be no more comfortable life and their mother had to work hard to keep things together, although Amelia, a resourceful girl, tried to help her mother where she could.

Amy’s mother died on 21 February 1912 and her father just a few months later, on 9 May, leaving a substantial amount of money to be shared among their four children. Judge Otis had become more and more concerned about Edwin’s drinking habits and the lack of provision he had made for his family. Amelia Otis had come to the same conclusion and so, to ensure Edwin could not squander any money left to Amy in the will, her share was put into a trust for up to twenty years; however, it was decreed that should Edwin die within that period the funds could then be released to Amy. When Judge Otis died at the age of 84 he put the same wording as his wife in his will, ensuring the money was held in trust so Edwin could not get his hands on it.

Edwin was not at all happy about that arrangement. He made efforts to regain his employment with the Rock Island Line, but was unsuccessful, and further applications to other railroad companies also failed. However, in 1913 he had some luck when he was offered a position with the Great Northern Railroad in St Paul, Minnesota, though at a much lower grade than he had had at the Rock Island Line. The family found themselves on the move again, this time to St Paul, where Amelia was to attend the Central High School. Life was hard for the family, much of the pressure due to the increased household expenses that Amy tried to deal with. Meanwhile, Amelia worked hard at school and demonstrated how bright she was. She was involved in playing a lot of sport, but found herself becoming disillusioned upon observing how boys were favoured above girls – something she found desperately unfair and at odds with her intrinsic belief in equal rights for all. The girls gradually settled down and were finally beginning to enjoy a more social life with their school friends when Edwin told the family that he had been offered another job at the Burlington Railroad’s office in Springfield, Missouri, replacing a man who was retiring. Edwin and the family travelled to Springfield in 1914 only to find that the man he was to replace had decided not to retire after all. This was too much for Amy and she made the decision to take the girls to stay with friends in Chicago to give them some stability. The girls attended school and Amelia made every effort to study hard, graduating from Hyde Park High School in 1916.

Meanwhile, Edwin went back to Kansas City and lived with his own family while he established his law practice. He made significant progress in untangling his life, and his efforts impressed Amy enough for her to decide to return to him, with the girls, to live in Kansas City, although it must be said the girls were not very keen on the idea.

Once together again both Edwin and Amy were keen to get their financial situation under control and attempts were made to take control of her inheritance that was in trust. On examination of the trust fund, however, it was discovered that it had been inefficiently managed by her brother, Mark, so Amy took legal action to seize control of it. During this process Mark died and the courts finally ruled that Amy could take charge of all assets.

Amy had been concerned over Amelia and Muriel’s education and was now in a position to send them to private schools in preparation for college. Amelia was to attend Ogontz School for Girls in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, as a boarder, commencing in October 1916, while Muriel went to St Margaret’s College in Toronto, Canada.