Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

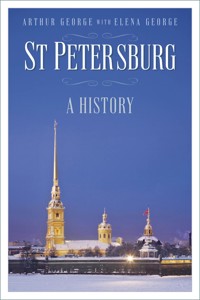

From its 1703 foundation by Peter the Great in a swampy war zone to its leading role in overthrowing Soviet power and bringing Russia into the twenty-first century, St Petersburg has undergone several transformations. Virtually commanded into existence by Peter the Great, the inherent artifice of St Petersburg has made it one of the world's most storied cities – the stage for political and artistic dreamers. As such, it had a leading role in nineteenth-century cultural life, but with the Russian Revolution of 1917 its glorious history descended into violence and bloodshed. During the Second World War, Leningrad suffered further atrocities in the form of a horrific Nazi siege. Yet it has remained rich in cultural, intellectual and architectural history. It has been home to greats such as Dostoevsky, Tchaikovsky and Nijinsky – figures who were gifted with great creativity and passion, and who were often dissatisfied with Russian traditions. These characters are explored by the author, together with the beguiling physical appearance of the city – canals, bridges, promenades and palaces – but the most lively writing hones in on the interplay between power and intellect, reaction and reform. Arthur George brings to life a St Petersburg steeped in a tumult of war, revolution and aesthetics, and shows it rising from the ashes to help lead Russia on the path to modernisation.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 1688

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Plan of St Petersburg, 1717–21. Anonymous engraver, published by J.B. Homann. (Courtesy National Library of Russia, St Petersburg)

In Petersburg we’ll meet again,As if the sun we buried there . . .

– OSIP MANDELSTAM

Petersburg is both the head and heart of Russia. . . . Even up to the present Petersburg is in dust and rubble; it is still being created, still becoming. Its future is still in an idea; but this idea belongs to Peter I; it is being embodied, growing and taking root with each day, not alone in the Petersburg swamp but in all Russia.

– FEDOR DOSTOEVSKY

Front cover image: Peter and Paul fortress, St Petersburg. (Svetlana Kuznetsova/Alamy Stock Photo)

First published in the USA in 2003 by Taylor Trade Publishing

First published in the UK in 2004 by Sutton Publishing

This paperback edition first published in 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Arthur L. George, 2003, 2004, 2024

The right of Arthur L. George to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 75099 625 9

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall

Jean Baptiste LeBlond. Plan of St Petersburg, 1717.

Map of St Petersburg, 1753. Executed by I.F. Truscott, drawn by M.I. Makhaev.

Map of St Petersburg by A. Savinkov, published in 1825. It shows the flooded areas during the 1824 deluge.

Bird’s-eye view of St Petersburg, 1860s.

Situation on the Leningrad Front on 21 August 1941. (Source: Leon Gouré, The Siege of Leningrad, RAND/R-0378, published by Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 1962. Copyright RAND, Santa Monica, CA, 1962. Reprinted by permission.)

The German Advance to Tikhvin. (Source: Leon Gouré, The Siege of Leningrad, RAND/R-0378, published by Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA, 1962. Copyright RAND, Santa Monica, CA, 1962. Reprinted by permission.)

Praise for St Petersburg

‘Arthur George’s book is an outstanding accomplishment, in the best tradition of grand history. He has succeeded marvelously in capturing what this complex city is all about. Both well researched and entertaining, this is the best book about St. Petersburg that I have read in a long time.’

Blair Ruble, Director, Kennan Institute of Advanced Russian Studies at Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington DC

‘Arthur George does a remarkable job of weaving together a wide range of sources to tell the multifaceted story of the city engagingly and in a way that has never been done before. He conjures up the city’s past in all its diversity, illuminating the many ways that the past lives on in the present. If I were traveling to St. Petersburg for the first time, this is the book I would want to read.’

Barbara Alpern Engel, Chair, Department of History, University of Colorado

‘In chronicling St. Petersburg’s first three centuries, Arthur George confidently anchors the city’s vibrant story within the larger narrative of Russian and Soviet history. This sweeping account represents an accomplished labor of love that will engage, enlighten, entertain – and provoke, in the very best sense of the word.’

Donald J. Raleigh, Professor of Russian History, University of North Carolina

‘Arthur George captures the exciting events, passions and brilliance of the Northern Capital’s history with the dispassionate, yet interested, hand of a true historian, in a style that his readers will find stimulating and fascinating.’

Irwin Weil, Professor of Russian and Russian Literature, Northwestern University

‘An astonishing accomplishment satisfying on many levels, this book is shaped by a unifying vision and rests on a broad knowledge of Russian history, written sources, and intimate personal familiarity with St. Petersburg as a living organism. Its judicious use of entertaining detail vividly recreates specific times, events, places, and personalities, while its historical analysis linking past and present is thought-provoking yet balanced, and refreshingly free of emotional ballast or visionary agendas.’

C. Nicholas Lee, Professor Emeritus, Department of Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures, University of Colorado

‘Reading the last chapters was like reliving my youth!’

Boris Andreyev, Honoured Statesman of the Arts of Russia, Assistant Professor, St Petersburg University of Cinematography and Television

Contents

PREFACE

PROLOGUE A TALE OF THREE CITIES

Chapter 1.

A Giant’s Vision: A New National Life

Chapter 2.

Building Peter’s Paradise

Chapter 3.

Life in Peter’s Paradise

Chapter 4.

Decline and Rebirth

Chapter 5.

Looking Like Europe: Elizabeth’s Petersburg

Chapter 6.

Thinking Like Europe: The Petersburg of Catherine II

Chapter 7.

Petersburg under the Errant Knight

Chapter 8.

Crossroads: Alexander I and the Decembrist Rebellion

Chapter 9.

Pushkin’s St Petersburg, Imperial St Petersburg

Chapter 10.

Dostoevsky’s St Petersburg

Chapter 11.

From World of Art to Apocalypse

Chapter 12.

Cradle of Revolution and Despair

Chapter 13.

Becoming Leningrad: The Revenge of Muscovy

Chapter 14.

Hero City

Chapter 15.

Rocking the Cradle

Chapter 16.

The Revenge of St Petersburg

SOURCE NOTES AND PHOTO ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING IN ENGLISH

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Preface

I became enraptured with St Petersburg (then called Leningrad) upon my first arrival there in 1979 as a student of history and Russian studying at its university. It was June and our plane had touched down at about 11p.m. While our group waited outside Pulkovo air terminal for our bus, a lazy red sun still hung low over the runways, refusing to set, and as we drove into town the light held. After arriving at our dormitory near the Peter and Paul Fortress, I stashed my things in the room and immediately broke curfew to take a midnight stroll along the banks of the silvery Neva and enjoy a few moments of solitude and reflection on that poetic White Night. I found no solitude, but there was much to reflect upon. On the embankment were scores of romantic couples, young and old, and other Leningraders strolling about in calm and contented silence, gazing and whispering in reverent, loving admiration of their surreal city. Upon seeing the eighteenth-century palaces lining the opposite shore (Palace Embankment), it seemed that had I been on this spot 200 years earlier, the scene and the feeling would hardly have differed. I recalled another midnight stroll through the bustling Latin Quarter of Paris upon my first visit to that city the year before. That too was a memorable experience, but it did not compare. It seemed to me that the wrong city is called the City of Light.

Soon afterwards I visited Moscow. I still remember how, as our bus lumbered into town from the airport, our local guide told us that we would enjoy Moscow more than Leningrad because it is a more ‘Russian’ city. She espoused the view of many that Leningrad was somehow odd and foreign, not really Russian. Although I was already familiar with the differing histories and traditions of these cities, this was my first direct encounter with the clashing mind-sets that their pasts had imparted on their citizens. The topic of St Petersburg’s place in Russia fascinated me, and as I continued my studies I came to agree with those historians who found strong parallels between Russia’s Muscovite past and the Soviet regime, and explained much of the latter by the former. The pressing question was how to escape this wheel of history. It was therefore of interest that an escape had been tried before, in St Petersburg.

During that first visit, the USSR was still ruled by Brezhnev. Years later, beginning in January 1989, I (together with my wife, who hails from St Petersburg and with whom I was also smitten while a student there) lived nearly four years in Moscow and then nearly five in St Petersburg, where I opened and headed my firm’s office. We lived through the era of Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost, the loss of Soviet satellites in Eastern and Central Europe, the August 1991 coup with Yeltsin’s speech atop a tank outside the White House and the break-up of the USSR. We saw St Petersburg re-emerge as a leading progressive force with a new spirit of hope. Many sincere and enlightened Russians, particularly from St Petersburg, strove mightily to turn Russia around, but they seemed outnumbered and crushed by the heavy weight of the past; many hopes were dashed. We saw the reappearance, in various forms, of the ‘Russian idea’. We saw the brown-shirt nationalism of Pamyat and Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the continued appeal to the communist crusade, various other claims to Russia’s special mission, suspicion of the West, continued corruption and cronyism in government, the struggle for the rule of law, and the emergence of the Mafia, the oligarchs, and others who considered themselves above society and restraint. Much of Russia still did not ‘get’ what it took to be a modern, open society.

After moving to Chicago, I attended a luncheon with Sergei Kiriyenko shortly after Boris Yeltsin had dismissed him as prime minister. Kiriyenko, an enlightened progressive who had found it difficult to implement reforms, told me that the most important factor holding Russia back is the mentality (soznanie) of most of its people, and that changing that mentality would be the key to progress and to Russia’s joining the modern world and community of nations. Shortly thereafter I read a Russian newspaper article which quoted alienated St Petersburg youth as holding that it is impossible to live in contemporary Russia and not be postmodern. Russia’s fate was still in the balance. Peter the Great’s vision was still a work in progress. Yet as I worked on this book, progress was being made in Russia, led by important reformers from St Petersburg. The original vision was still there and held, increasingly, within the nation’s grasp.

During those historic years in the USSR and Russia, friends and colleagues often urged me to keep a diary and write an account of my experiences, particularly since my work as a lawyer put me at the cutting edge of developments and in regular contact with many leading figures of the day. Busy living history, I never seemed to find the time to write it. In truth, such a project did not inspire me. I did not want simply to compile a journalistic observation of famous events that I lived through and participated in. Instead, my interest kept returning to Russia’s fundamental ‘accursed questions’. Besides reading daily press accounts of revolutionary changes, I reread Gogol and remembered what had not changed. The age-old accursed questions were still playing themselves out before my eyes, and even made things difficult in my job. Historically, the drama of these questions had unfolded first and foremost in the city of St Petersburg, and the ending was still to be written.

When the late Anatoly Sobchak was mayor of St Petersburg, he used to give a speech (which I heard several times) outlining his vision of how St Petersburg would call upon its great past and potential and re-emerge as Russia’s locus of political and intellectual enlightenment and its centre of trade, finance, shipping, and tourism, leading Russia into a prosperous, democratic, and enlightened future. Warming to the subject, he would add that this in turn would help ensure the stability of the central Asian subcontinent and lead to world peace in the twenty-first century. The first part of this was hardly original but rather was a St Petersburg tradition – Peter the Great had instituted this same vision, and some of it came to pass. As to the second part, one can only hope so. Whatever the case, the challenges facing post-Soviet Russia had placed the city’s original role and relevance to the new Russia front and centre.

By the time I returned to America from St Petersburg in late 1997, the city was already planning its tercentenary celebrations for 2003. This in itself, together with the fact that no English-language narrative history of the city yet existed, seemed to make publishing one timely. But ultimately it was my fascination with the city’s role and meaning in Russia’s tortuous history and my conviction that an understanding of this history can be instructive for the present that finally inspired me to write this book rather than another as the first literary fruit of my Russian studies and life there. In arriving at an organizing theme for this story, I was aided by the historian Aileen Kelly’s observation that the city’s tragic mythological aura that engulfs so many literary and prose writings about the city – however fascinating and which even as myth and literature forms an essential part of the city’s history – is ultimately inadequate to explain Petersburg’s overall historical significance or its potential role in the new Russia.1 Rather, as I watched post-Soviet Russia struggle to modernize and move towards a civil society and new national life and as Petersburgers and their ideas assumed a leading role in this struggle, it seemed to me that the modernizing changes introduced beginning nearly three centuries earlier and of which Petersburg was to be the embodiment had acquired a new relevance, and that these changes and the values underlying them also stood apart from the values of what eventually became known as ‘Imperial St Petersburg’. In today’s global information society, the idea that a single city as a geographical or economic unit can play the kind of unique vanguard role envisaged by Peter and dreamed of by Sobchak needs a stretch of the imagination. But Petersburg was nothing if not a city of ideas, and technology has shrunk Russia’s geographical expanse that observers throughout history have believed necessitated despotism rather than government according to the liberal ideas that became associated with the city; perhaps the present heralds the first realistic opportunity for these ideas to be achieved. It struck me that people would be helped by a better awareness of the instructive historical dramas played out in Petersburg’s past, because some of them are being repeated. I became convinced that, in today’s world of globalization, a book exploring the city’s unique history from the perspectives of modernism, movement towards civil society, common human values and world culture would be interesting and timely. From this perspective, Petersburg is not just a Window to the West, but a Window to the Future, and not just Russia’s.

Since Petersburg was founded in 1703 with a mission to change the national life, in order to understand Petersburg one must understand something of Russia before 1703. Thus, the book opens with a prologue recounting the formative themes of Russian history leading up to Peter the Great and the founding of St Petersburg. Since through the reign of Nicholas I each sovereign in Petersburg left his or her unique imprint on the city and most progress (or regression) was driven by the imperial court, chapters 1–9 are organized around the reigns of Russia’s rulers. Thereafter, the chapters are tied to major historical events and themes rather than to rulers. From the perspective of the city’s social, intellectual, and political history, its story divides into four phases: the evolution of Peter the Great’s vision and reforms until early in the reign of Catherine the Great; the emergence of a liberal opposition late in Catherine’s reign culminating in the Decembrist uprising in 1825; the era of disparate searches for solutions, repression, radical opposition, and social and political unrest culminating in the establishment and consolidation of the Bolshevik regime; and the subsequent struggles of the city’s people to escape from the Soviet regime and live in a modern, open society.

While political and intellectual history and the theme of modernism form much of this book’s conceptual framework, the city’s unique culture (and in particular themes of world culture) is also an essential theme and provides much of the picture inside the frame. Indeed, most of the book is devoted to this fascinating picture, which does prominently include the story of the city’s tragic mythological and mysterious aura, as well as what one can discern as its ‘soul’. Peter the Great founded the city intending it to be an ideal (utopia) of civilization and culture, a vanguard for Russia and even for Europe. While political and social reform ultimately lagged, in many respects Petersburg long ago achieved its purpose in the cultural sphere, synthesizing the best of Russia and Western Europe to create new art that stunned and conquered Europe. Petersburg developed its own special intellectual and artistic vigour, architecture, culture, beauty, mystery, spirit, and rhythm of life that form its soul, which is incomparable and stems from the city’s unique place in geography and history, and from the daring, unbridled imagination and spirit of its people. It was embodied in such figures as Alexander Pushkin, Peter Tchaikovsky, Vladimir Nabokov, Kasimir Malevich, Alexander Benois, Pavel Filonov, Igor Stravinsky, Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Nikolai Gumilev, George Balanchine, Nikolai Antsiferov, Mikhail Baryshnikov, Joseph Brodsky, Dmitri Shostakovich, and Dmitri Likhachev. Alongside the political turmoil, this life has always gone on, and the city has stood patiently and beautifully on the banks of the Neva, hoping for the nation’s political life to catch up and awaiting its chance again to play an important role in that process.

I wish to thank the many people who helped create this book. Among the specialists who kindly offered their consultation, I wish to thank Lev Lourie, the prominent St Petersburg historian; Blair Ruble, Director of the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies; Anatoly Belkin, noted St Petersburg art historian; Vladimir Sanzharov, Chairman of the St Petersburg branch of the Union of Designers of Russia, a specialist on city planning and architecture; Andrei Burlaka, specialist on the history of Russian rock and roll; Gennady Golstein, famous jazz band leader and instructor at the Mussorgsky School of Music, for his consultation on the history of jazz in St Petersburg; Richard Torrence, former adviser to Mayor Sobchak; the writer Valery Zavorotnyi for his assistance regarding the August 1991 coup; John Evans, former US Consul-General in St Petersburg and currently US ambassador to Armenia; Evgeny Fedorov, Tatyana Pasynkova, Nina Tarasova, and Elena Korolkova from the Hermitage Museum; and Lydia Leontieva of the Astoria hotel for information on the rich history of that city landmark. I also wish to thank the following friends in St Petersburg for their support, research assistance, and review of the manuscript: Boris Andreyev, Alexander Pozdnyakov, Vladimir Marinichev, and Lyubov Erigo. I thank Rimma Krupova and Yuri Ermolov for their assistance with the photographs and illustrations. Thanks also to the staffs of the Russian National Public Library in St Petersburg (particularly Elena Nebogatikova and Natalya Rudakova), the Lake Forest Public Library, the Lake Forest College Library, the St Petersburg office of my own firm, Baker & McKenzie, and to the firm as a whole for giving me the leeway to complete this project. Warm thanks also are due to my agent, Ed Knappman, my editor of the original US edition, Michael Dorr, both of whom had the vision to see the book’s potential and guided me through the minefields of the publication process, and to Anne Bennett, my editor at Sutton for her hard work in anglicizing the text. But most of all I thank my wife Elena, whose love and support got me through the project. Because of her love for and knowledge about her native city, she worked tirelessly in assisting with research, offered many stimulating ideas, and was my best critic and editor, all of which led to many late-night discussions and helped give the book the shape it has. Without her there would be no book.

Generally, the book gives dates from 1700 according to the calendar in use at the time. The Julian (‘Old Style’) calendar was used in Russia from 1700 until 1918, when the Gregorian (‘New Style’) calendar was adopted. To get New Style dates, one must add 11 days during the eighteenth century, 12 days during the nineteenth century, and 13 days during the early twentieth.

In transliterating Russian words into English, I have generally followed a modified version of the Library of Congress system for general works described in J. Thomas Shaw, The Transliteration of Modern Russian for English-Language Publications (New York, 1967), without diacritical marks, while making some concessions to common usage to make the text more readable. Translations of quoted texts originally in Russian are my own unless otherwise indicated. Quotations from texts originally with American spellings have been anglicized in order to achieve uniformity in this edition.

Lake Forest, IllinoisOctober 2004

PROLOGUE

A Tale of Three Cities

There have been five periods in Russian history and each provides a different picture. They are: the Russia of Kiev; Russia in the days of the Tartar yoke; the Russia of Moscow; the Russia of Peter the Great; and Soviet Russia. The Moscow period was the worst in Russian history, the most stifling, of a particularly Asiatic and Tartar type, and those lovers of freedom, the Slavophils, have idealized it in terms of their own misunderstanding of it.

NIKOLAI BERDYAEV1

St Petersburg has often been considered a stranger in its own land, an unnatural aberration situated on the far edge of the nation – not really Russian. St Petersburg is indeed unique, but Russia’s three previous major cities – Novgorod, Kiev, and Moscow – have also lived separate and distinctive lives. In fact, St Petersburg, Novgorod, and Kiev enjoy many similarities, while in important respects Muscovite civilization is the anomaly, particularly if viewed in terms of world history. Most major world cities, including capitals, lay either on the coast or not far up navigable rivers, because this facilitates trade, prosperity, and interaction with other nations, and stimulates culture. Novgorod, Kiev, and St Petersburg followed this norm, while due to historical accident (the Mongols) Muscovy arose deep inland with no ready access to the sea. This had pernicious consequences that eventually had to be redressed.

Peter the Great’s reforms and St Petersburg itself should be understood not as unnatural aberrations but as logical and natural responses to the inevitable seventeenth-century crisis of Muscovite civilization. Later, in the twentieth century, the rise and staying power of Soviet Communism can be understood as a reassertion and embracing of old Muscovite traditions and values, and a rejection of those of St Petersburg. The crisis of the Soviet system that led to its downfall has parallels to the crisis in seventeenth-century Muscovy. Many of the ideas and values required for Russia’s post-Soviet revival and entry into the modern world of nations can be found in the history of St Petersburg, beginning with its founder, Peter the Great. The city’s history and meaning holds lessons for Russia’s future and can help guide it.

It is thus important to begin the story of Petersburg by examining how Novgorod, Kiev, and Moscow have each bequeathed their unique traditions to Russia and St Petersburg and enriched the city’s life. Events and personalities from their histories appear in Petersburg’s art, music, opera, ballet, literature, and poetry, as well as in political and intellectual controversies. Their histories help explain why St Petersburg was founded and provide the context to give the city its meaning and interpret its development.

One can summarize the historical interplay between these three cities only by illustrating its complexity. There was no uniform historical line of succession or influence among them, and in many ways their civilizations were rival. Novgorod spawned Kiev, but Kiev grew close to Byzantium and adopted its religion, and then violently imposed it on Novgorod. Muscovy grew up largely outside the Kievan state but embraced and developed its religion. It matured under the Mongol yoke without meaningful contact with Constantinople or the West, becoming the dominant force in Russia in part because its princes represented the Khan in dealings with other Russian princes and nobles. Kiev fell to the Mongols in 1240, but when the Mongols were repelled, Kiev and what would become Ukraine were absorbed into the Polish-Lithuanian state. When Ukraine rejoined Russia four centuries later on the eve of the founding of St Petersburg, the culture and learning that it had acquired while outside Muscovy’s influence inspired fundamental departures from Muscovite culture and thinking, influenced Peter the Great’s reforms, and contributed to the intellectual, religious, and political life of the new capital. For its part, Novgorod, previously part of the Kievan state, remained an absent, independent republic in the north with its own traditions. Muscovy not only drew little from it, but it became Muscovy’s commercial and political rival, and Muscovy eventually decided to crush it.

Novgorod

Novgorod’s initial contribution to Russian civilization was political and economic and came early. According to the Primary Chronicle, the tribes of the region constantly quarrelled, and social and political disorder reigned in the land. Tradition held that the tribal leaders, unhappy with this state of affairs, invited a Viking prince, Rurik, who founded Novgorod (‘New City’) around 860 and ruled as its prince. His descendants and relatives, most notably Oleg, Sviatoslav, Vladimir, and Yaroslav the Wise, later ruled in Kiev and presided over its Golden Age. The Rurikid line of princes continued through most of the Muscovite period, until the death of Tsar Fedor (the son of Ivan the Terrible) in 1598.

In the same year that Kiev fell to the Mongols (1240), Prince Alexander led Novgorod to victory over the Swedes on the banks of the Neva near the future St Petersburg, for which he acquired the sobriquet Nevsky. Two years later he defeated the Teutonic Knights on the ice of Lake Chud (now Peipus), thereby eliminating military threats from the north and west. Security thus assured, and essentially free of the Mongol yoke, Novgorod went on to prosper through trade and contact with the West, particularly with the Hanseatic League, of which it became a member. Novgorod was on the axis of the great north-south trade route between the Vikings and the Greeks, and was also a centre of trade with the East via the Volga river. The northern section of the route ran from the mouth of the Neva (where St Petersburg was later founded), along the length of the Neva, through Lake Ladoga, and down the navigable river Volkhov which connected Ladoga to Novgorod and Lake Ilmen just south of Novgorod. So long as Novgorod controlled these territories, it grew and prospered, but when it lost them to Sweden the city declined. To regain its position in international commerce, develop its national economy, and maintain effective contact with the West, Russia needed access to the Baltic, but this was not re-established until the reign of Peter the Great.

As a cosmopolitan urban trading centre not unlike Venice or other progressive medieval Western European city-states, Novgorod developed an urban civilization unique in Russia, as well as democratic and tolerant political and cultural traditions. It used a Germanic monetary system, a large community of foreigners lived unhindered in the city, its citizens travelled and established communities abroad, and its princes and leading citizens often married foreigners. Women were generally treated as the equals of men and participated in civic affairs. Wealth was sufficiently high to maintain education and high literacy, and to support art and architecture. Unlike Muscovy, in Novgorod most wealth and power lay with a powerful merchant class, which kept the ruling prince and the Church in check. Whereas Moscow’s Grand Princes gained power by ‘gathering’ the Russian lands as their own and administering them as their patrimony, in Novgorod property and sovereignty were understood as separate, and institutions were created to curb and control the exercise of political power and protect property and citizens’ rights in it. Novgorod’s prince was selected and hired by the people, and he functioned pursuant to a contract setting forth his powers and the restrictions on them; if the people grew dissatisfied, he could be replaced. All major decisions were made by democratic public assemblies called a veche, which met on both a city-wide and district level, and at which each free householder had a vote. An advanced legal code was developed, criminal punishments were generally humane with an emphasis on fines, and human life and the individual were held in high regard. Thus, a reciprocal relationship between the state and society was recognized, whereby the vital activity within the state lay with its citizens, who created their government to protect their rights and property, and provide security. This anticipated Western political thought by centuries and was fundamentally different from the idea of a divinely ordained monarch prevalent in Muscovy and the Old Regime in Western Europe.

Out of this economic, political, and cultural milieu grew a tradition of civic and individual independence (even irreverence), vigour, tolerance, and imagination. It stands in stark contrast to the worldview of the rest of Russia during and after the Mongol period, until St Petersburg. A poignant example was the fresco of the Saviour in the main cupola of St Sophia Cathedral in the city’s kremlin: his hand was portrayed not, as is usual in Moscow, partly open and relaxed as when crossing oneself, but as a fist symbolizing strength and independence, even defiance. Even the Orthodox monastery constructed on Perun hill outside town where pre-Christian pagan rites were held was named Our Lady of Perun, after the pagan god. This would have been unthinkable in Moscow. Before Moscow conquered Novgorod, the city’s seal consisted of a flight of steps representing the veche tribune and a T-shaped pole representing the city’s sovereignty and independence. Under Muscovite rule, the steps assumed the shape of the Tsarist throne, and the pole that of the Tsar’s sceptre.2

Feeling commercial competition, needing tax revenues, and demanding political subservience, Muscovy under Ivan III conquered Novgorod in 1471. He arrested thousands of Novgorodians, who were either killed or deported en masse, and confiscated their property. He eliminated the veche, and its famous bell was taken down and shipped to Moscow. In 1494 Moscow expelled the Hanse from the city, arresting its members and confiscating its property. When Novgorod recovered over the next century and was once more perceived as a threat to Moscow, it suffered utter devastation from Ivan the Terrible in 1570, when he (probably falsely) accused Novgorod of plotting with Poland to overthrow him. In an infamous incident, Ivan invited the town’s leading citizens to dinner in the Faceted Chamber in Novgorod’s kremlin, where his guards murdered them. About one-third of the city’s population perished in a massacre that lasted weeks. Ivan then removed the city’s main library, which contained many ancient and priceless manuscripts, and buried it in secret chambers under the Moscow Kremlin, where it remains lost to this day. Thus was smashed Russia’s most important link to the West, which had survived the Mongol invasion. Whereas Kiev had been lost to the Mongols, Novgorod was crushed by fellow Russians.

Peter the Great was impressed by Novgorod’s history and traditions and held many of them up as models. After Petersburg was established, in 1724 Alexander Nevsky’s remains were transferred to St Petersburg’s principal monastery, Alexander Nevsky Monastery, to symbolize Petersburg’s links with Novgorod’s history and traditions. St Petersburg’s main street, which connects the city’s centre to the monastery, was eventually named after him (Nevsky Prospect). When legends about the founding of St Petersburg first began to circulate, a popular one in the north was that St Andrew the First-Called* had visited the future site of Novgorod as well as the mouth of the Neva, the site of the future ‘reigning city’ (tsarstvuyushchii grad).3 This legend linked Novgorod and Petersburg as centres of Russian civilization. Later many Petersburg liberals, including Alexander Radishchev,4 the Decembrists,5 Alexander Herzen,6 and playwrights,7 identified with Novgorod’s traditions when advocating their progressive agendas for Russia. Today, Novgorodians proudly assert that Peter the Great and St Petersburg continued directly many of the essential traditions of Novgorod.

Kiev

The Kievan state was founded in 882 by Prince Oleg, one of a line of Viking princes related to Prince Rurik of Novgorod. Kievan civilization reached its zenith under Vladimir and his son Yaroslav the Wise from the late tenth to mid-eleventh centuries. Its failure to develop stable political structures and its economic dependence on trade with Byzantium ultimately led to its demise.

Whereas Novgorod’s legacy is political and economic, Kiev’s is largely cultural and religious. When the Kievan state was founded, Byzantium represented the height of civilization, and Christianity had not yet split into Orthodoxy and Catholicism. Thus, Kiev not only learned much from Byzantium, but it also developed political, cultural, and dynastic ties with the West. Kiev’s prestige was so high at the time that many European monarchs sought alliances with Kiev through dynastic marriages. Vladimir’s daughters Premislava and Dobronega-Maria married the kings of Hungary and Poland. Henry I of France, who was illiterate, married Yaroslav the Wise’s daughter Anna, who was well educated and knew several languages. Yaroslav’s two other daughters, Anastasia and Elizabeth, married the kings of Hungary and Norway. Vladimir Monomakh’s daughter Praxedis married the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry IV. Indeed, Kiev’s civilization in many respects was ahead of Western Europe. Its laws were humane, citizens enjoyed freedoms, public education was progressing, commerce was sophisticated, and women enjoyed high status. Had Kiev developed the political and military organization needed to withstand the Mongol hordes, Russian history would be very different.

The key civilizing and cultural development in Kiev was Prince Vladimir’s adoption of Christianity from Byzantium in 988. One motivation for the conversion was Vladimir’s immediate political goals. The conversion was facilitated by Vladimir’s marriage to Princess Anna, the Byzantine Emperor’s daughter, which cemented political ties between the two civilizations while preserving Kiev’s political and cultural independence (by putting the prince on a par with the emperor as his brother). More importantly, the conversion left permanent marks on Kievan and (later) Muscovite society, serving to unify the Russian nation culturally and politically.

The new religion had to be propagated through a language. Kievan Russia’s alphabet, Cyrillic, received through Bulgaria, facilitated the development of the vernacular Slavonic into a written language, Church Slavonic, which remained the principal written language of Russia until the seventeenth century. Kiev’s adoption of this vernacular for Church purposes rather than the Greek or Latin texts available in Byzantium meant that Greek was not well known (and Latin virtually unknown) in Kievan and Muscovite Russia. Since these were the languages of classical and Western philosophical, religious, and historical works as well as of Roman law, Muscovite Russia’s access to and knowledge of much of classical and Western culture following the decline of Byzantium was severely limited. Kiev’s own absorption into the Polish-Lithuanian state exacerbated this problem for Muscovite Russia, while Kiev itself would exploit this link to grow into a centre of Greek and Western-inspired learning. As a result, classical thought had no meaningful influence in Russia until the St Petersburg era, when Kievan scholars played an important role in introducing this learning into Russia.

Also significant was the manner in which Christianity was introduced and practised. Since the society had no developed philosophical tradition or even literacy, Orthodox believers tended to adopt all aspects of doctrine and ritual uncritically, assuming that the religion’s founders had worked out to perfection all essential and necessary truths and rituals. Further, since Orthodoxy was forced on the population from above, often violently, there was little scope for theoretical discussion and more attention to form, although some concessions were made to graft Orthodoxy on to pagan rituals and practices. Finally, the Greek and Slav churchmen despatched to spread Christianity in this hinterland were by no means the best and most educated, and were often separated from their flock by language barriers. Consequently, they typically confined themselves simply to teaching the externals of ritual and collecting money for the Church.8

As a result, the mystical and ritualistic aspects of the new religion predominated. No sophisticated philosophical or theological tradition was transmitted from Byzantium or developed on its own. In a largely illiterate population in which pagan influences were still fresh and alive, the beliefs of Russian Orthodoxy came to be understood, conveyed, and appreciated not through theoretical or literary means but through its mystery and visual beauty, as represented by the liturgy and by icons. (Indeed, it was the beauty of the religion’s ritual which most impressed Vladimir’s emissaries sent to Constantinople to evaluate its suitability for Kievan Russia.) Icons and the icon screens in Orthodox churches served as a constant reminder of God’s power and constant involvement in human affairs, reinforced the social and political hierarchy in society, and, in the Muscovite period, supported the tsar’s place as the icon of God in the Orthodox empire, just as the Orthodox empire was the icon of the heavenly world.9

The focus on adherence to ritual and near absence of theology also meant that, unlike religion in Western Europe, deviations from the established beliefs and rituals were rare. When they did arise, they gained no large grassroots following and were short-lived, and while they did they were not tolerated. Because of this intolerance for change among both church leaders and believers, Russia’s isolation from Byzantium and then Byzantium’s decline, Russian Orthodox texts and rituals remained essentially unchanged until the mid-seventeenth century.

When the Mongols eventually lost Kiev and the surrounding area, it went not to Moscow but to the emerging Lithuanian state (soon to be the Polish-Lithuanian state). Thus, although its later shedding of the Mongol yoke might have given Moscow the benefit of Kiev’s civilizing and cultural influence, instead each developed along separate political and cultural lines for the next four centuries. Poland ceded Kiev to Moscow under the Treaty of Andrusovo in 1667, the year that marked the end of the Great Schism. Thereafter, Kiev’s learning helped Petrine Russia become a less religious and more secular, modern state.

Despite the future importance of these cultural and religious trends, they never dominated Kievan national life in the way they later did in Moscow. Kiev’s culture remained cosmopolitan, and the focus of its life continued to be trade between the Normans and the Greeks. When trade dwindled as Byzantium declined and the Crusades opened the Mediterranean to trade from Western Europe, so did the Kievan state itself. The government was not organized well enough to govern such a large territory. The roles and responsibilities of the prince relative to the veche (adopted from Novgorod) were ambiguous. The outlying towns and estates were not closely integrated into the state structure; the sole concern was whether they paid tribute to Kiev. Most importantly, no orderly scheme for princely succession was established, so that the land was constantly divided and ravaged by warring brothers and their supporters. This disorder made Kiev easy prey for the Mongols, who united under a strong leader. Moscow’s princes took notice of Kiev’s fate and were determined not to repeat the same mistakes. The result was an absolutism unparalleled in Europe.

Moscow

Historical sources first mention Moscow as a city in 1147, and Prince Yuri Dolgoruky is said to have laid the foundations of the town (i.e. the city wall) in 1156. At the time, the town was under the suzerainty of Suzdal, which lay outside the Kievan state. The Mongols invaded and destroyed it in 1237, just before Kiev met the same fate. Muscovy’s inheritance from Kiev was limited and consisted mainly of the Orthodox faith and forms of land ownership; Kiev’s political traditions and its civilized culture did not transfer to Muscovy. Instead, the influences of the Mongols and Orthodoxy combined to foster at the top an arbitrary autocracy and at the bottom a conservative, passive, uncritical populace wedded to habit and tradition.

Moscow and the territory surrounding it were under Mongol control until the late fourteenth century; it was in these conditions that Muscovite civilization matured. Mongol rule broke most contact with Western Europe and even with Kiev; it also eliminated the possibility of developing diplomatic and commercial contacts with Byzantium. The Mongol conquest and decline of Byzantium thus blocked what might otherwise have been a natural and continuous line of Russian political, economic, social, and cultural development more in line with that in the West. Instead, the new external elements introduced over the next two centuries were oriental traditions and oriental blood. No Moscow prince ever set foot in Constantinople, but they were regular visitors to their sovereigns in Sarai.

Mongol influences on Moscow included the Asiatic dress adopted by princes and nobles (known as boyars), a variety of Mongol words incorporated into the language (particularly those relating to state affairs), rampant corruption, and the low status and isolation of women. Mongol legacies were autocracy, obsequious loyalty to princes, and the rule that the people ‘pray only to one Tsar’. Muscovite princes adopted from Sarai a model of governing that limited their role to tax collection, keeping public order, and administration of patrimonial domains. No further secular conception of responsibility for public well-being existed. When Mongol rule ended, the practice of collection of tribute did not end; it was continued by the Muscovite Prince, who kept it for himself. No notion existed of a society separate from the sovereign which had any rights or with which it had reciprocal relations.

Mongol influence over Moscow began to wane after the Muscovite victory over the Mongols at Kulikovo in 1380 and Tamerlane’s campaigns, which ended in 1395. The yoke was formally broken in 1480, when Moscow refused to pay tribute. The Grand Prince designated himself autocrat (samoderzhets), meaning that he paid tribute to no one.

During the Mongol period, local ‘appanage’ princes rose up who operated vast estates, maintained order, and governed their localities. In order to defend themselves against Mongols, Turks, Lithuanians, Poles, and other outsiders, it was necessary and inevitable for these princedoms to unite, with one of them emerging on top. Beginning in the twelfth century and culminating in the late fifteenth with Ivan III’s subjugation of Tver and Novgorod, the inevitable shake-out occurred, and Moscow emerged the victor.

Understanding this shake-out process and why Moscow emerged victorious is fundamental to understanding the nature of the Muscovite civilization which developed, and which Peter the Great despised and sought to replace in St Petersburg. The lands were owned and run by nobles under a hereditary system called votchina, which had originated in Kiev. Within his own lands, the owner was sovereign and a law unto himself; he controlled not only property, but also the local economy, political power, and the administration of justice. In short, the land and its people were his patrimony. Yet the nobles owed little to the prince, who correspondingly had little formal control over or responsibilities to them, a fundamental weakness in the state. This situation differed from medieval Western Europe, where vassals bound themselves to lords by contract and an elaborate network of subinfeudation developed.

Moscow’s princes learned from Kiev’s weakness. Their initial approach was not to change the votchina system, but to become the chief landowner, to gain control of the entire land and make the entire nation the Muscovite Prince’s patrimony and the prince its absolute sovereign. Over time they also succeeded in introducing primogeniture in order to avoid the break-up of holdings and to preserve princely power. Once such ownership and control was achieved, the prince was able to reverse the process and grant landholdings, as typical in the West, on a non-hereditary basis in return for service. This system was called pomestie. Over time, the service nobility convinced the prince (later tsar) that they could best serve him if their peasants could not migrate. The rise in service obligations resulted in serfdom. Votchina declined, but the prince’s absolute authority was assured.

Since the entire nation (both land and populace) was essentially the tsar’s patrimony, the exercise of property rights and sovereignty (politics) were not separated. The distinction in Roman law between dominium and imperium (or iurisdictio), which had been preserved in the West and which led to private property and individual rights, was unknown in Muscovy; political authority too was exercised as dominium. State finances, for example, were essentially those of the prince himself; state administration was essentially that of the prince’s household (dvor) and properties. This process reached its apogee under Ivan III and remained fundamentally unchallenged and unchanged until the Petersburg era, when Peter sought to institute a new model based on Western conceptions of property, state, and society. Much of this Muscovite legacy, including the preference of many for state ownership of land, survived right through the Soviet regime.

Similarly, unlike the West, in Muscovy there was no developed concept of a society in which the ruler had a reciprocal relationship with his subjects, who had certain rights and to whom the ruler owed particular duties. Even the modern Russian word for society (obshchestvo) did not yet exist; there was only the concept of zemlya, which today carries a narrow meaning of ‘land’ but which at the time was understood as income-producing property and its people, the object of the prince’s exploitation.10 The Russian word for state (gosudarstvo) comes from gosudar, which, prior to being used as the word for ‘sovereign’ in reference to princes and tsars, was the word for a slave owner and thus connoted authority in the private sphere (dominium). In this climate, the nobility was never able to emerge as a separate estate or order with its own common interests (and eventually rights), which could eventually pave the way for a civil society. This would begin only after Peter the Great’s reforms, in the reign of Catherine II.

The reasons why the prince of Moscow emerged as the leader have much to do with why it became the ‘soul of Russia’, with which Peter the Great and St Petersburg are contrasted. Although there is much to be said for the skill of Moscow’s princes, initially Moscow’s most fundamental advantage was geographical: it was far enough into the interior not to be easily accessible from distant Sarai on the lower Volga, and it was located in dense forest at the junction of two rivers, conditions which rendered the Mongols’ cavalry-based attack ineffective. These conditions forced the Mongols to rule with a lighter and more distant hand than in other areas, which ultimately allowed Moscow’s princes to gather strength. In particular, in gratitude for Moscow’s assistance in crushing the 1327 revolt of Tver (Moscow’s rival) against the Mongols, the Khan put Ivan I in charge of collecting their tribute from neighbouring Russian princes. The Mongols bestowed on him the official title ‘Grand Prince’, though he became known then and to posterity as Ivan Kalita (‘moneybag’). His role as tribute collector gave Moscow authority over rival princes and isolated them from having direct relations with the Khan. Also, like any effective tax collector of the time, Kalita garnered more taxes than he remitted, and enriched himself and Muscovy (which were hardly distinguishable). Once Mongol power began to decline and a challenge became possible, Moscow was well placed to ‘gather’ Russia. By delegating their fiscal powers, the Mongols had created their own nemesis.

Another force which fuelled Muscovy’s rise to prominence, united its people, and determined the civilization’s character was the Orthodox Church. Ivan Kalita added to his domain the town of Vladimir, which after Kiev’s fall had become the seat of the Orthodox Metropolitan. After Metropolitan Peter died in 1326 and Moscow defeated Tver in 1327, Peter’s successor aligned himself with Moscow and moved Orthodoxy’s seat there. Thereafter, Moscow’s princes and the Church worked hand in hand to increase each other’s power and influence.

Understanding the religious character of Muscovite civilization is crucial to understanding Moscow as Russia’s ‘soul’, and how it differed from Peter the Great’s ideas and the civilization of St Petersburg. A first important feature was Orthodoxy’s simple asceticism and the associated monastic movement, epitomized in the 1330s by St Sergius of Radonezh, who eschewed rational theology and favoured direct contact with God through achieving an appropriate mystical inner spiritual state.

Notwithstanding the mysticism and asceticism of the faithful, the Church hierarchy and the Grand Prince inaugurated a monastic crusade designed to consolidate Moscow’s territorial gains with monastery-fortresses and spread a uniform Orthodox faith. In 1503 the abbot Joseph Sanin persuaded a Church council to allow monasteries to accept land grants (fully equipped with peasants) from the Grand Prince and nobles. These monastic landholdings were still under the protection and ultimate control of the prince and remained his patrimony; in return, he expected and received ecclesiastical support. Sanin was also strict on matters of doctrine, sought to root out heresy, and resorted to torture and executions, which became accepted practice. Sanin’s efforts were opposed by Nil Sorsky, whose adherents became known as the ‘non-possessors’ since they opposed gifts of land to monasteries. Sorsky sought to preserve a more pure and spiritual brand of Orthodoxy, uncorrupted by vast properties and involvement in temporal matters. He was thus tolerant in matters of belief and supported the church and state keeping to their separate realms.

But Sanin’s approach, known as Josephism, was a winning proposition for the prince and fused the alliance between Church and tsar. Church holdings became immense and serfdom spread. Princes and nobles endowed the Church with their wealth to ease their consciences in the hope of salvation and also to avoid taxes. The Monastery of the Trinity founded by St Sergius outside Moscow in 1335, for example, had at least 100,000 serfs cultivating its lands by 1600. Monasteries often focused more on their role as landowners than on religion. This process subjected the formerly loosely bound ascetic communities to the Moscow Metropolitan’s power. With the victory of Josephism, Muscovy itself came to be conceived of as a national monastery under the direction of the tsar, in whom ‘the opposition between Caesar and the will of God was overcome’.11 But in practice the tsar dominated the Church. Josephism helped set the stage for Russian autocracy as it emerged under Ivan the Terrible.

Josephism also helped generate Orthodoxy’s messianic ideology, which conceived of Russia as a divinely chosen, special and superior nation destined to lead the rest of the world to salvation. Once developed, it remained a fundamental part of the Russian mentality, continuing during nineteenth-century Slavophilism and indeed in Soviet communism. This vision coalesced in the mid- to late fifteenth century. At the Council of Florence in 1437–9, Byzantium, hoping to attract Western help in its struggle against the Turks, agreed to compromises which it hoped would unify Catholicism and Orthodoxy. Moscow rejected the arrangement and arrested Isidore, the Greek Moscow Metropolitan who had attended the Council and agreed to it. Moscow believed that Byzantium had betrayed the faith, which Byzantium’s fall shortly thereafter (1453) seemed to confirm. It was God’s retribution against an unfaithful people, the result of a corruption of the Greek Orthodox faith and Greek society.

Moscow now viewed itself as Byzantium’s successor, which Ivan III symbolized by marrying Sophia Paleologus, the niece of the last Byzantine emperor, in 1472, and by adopting the Byzantine double-headed eagle as the imperial seal.* Ivan III took the title ‘Tsar’ (meaning Caesar), symbolizing his claim to inherit all political and religious authority of the fallen Byzantium. Thus arose the theory and widespread belief that Muscovite Russia was the ‘Third Rome’, a term first coined by Philoteus, a monk from Pskov, who called the tsar ‘the only Tsar of Christians’.12 The first two (Rome and Constantinople) had fallen as a result of deviations from the faith and, because Moscow would last forever (or at least until the Apocalypse), there could be no fourth. The tsar’s role was not merely that of autocrat but of the divinely ordained head of a religious civilization. Muscovite Russia thus represented the culminating stage of a pre-ordained progression in sacred and world history, with the tsar at its apex. Since Muscovy was God’s and history’s chosen repository of perfect and undivided Orthodoxy, there was no scope for further historical development, only the wait for the Second Coming and the end of earthly life, and there could be no dissent on the question. (Bolshevism held similar views.) Originally the doctrine of the Third Rome was principally a religious concept, deeming Russia the successor to the pure and right teaching,13 charged with preparing humanity for the Second Coming and salvation. For the tsar, however, it also implied the exercise of temporal authority. It was only a short step to make it an imperial doctrine as well. The tsar must unite the Orthodox world and prepare it for the Second Coming. The doctrine justified extending Orthodoxy (and the tsar’s power) to new lands, and for rooting out opposition within his own. The tsar’s temporal pretensions and Orthodoxy’s spiritual doctrines reinforced each other.

Thus arose Muscovy’s conservatism, arrogance, lack of interest in, and xenophobic suspicion of anything and anyone not Orthodox and not Russian. This attitude extended to intellectual activity in general and to science, as well as to innovations (seen as deviations) in elements of culture on which the Church touched, such as music and art, which were viewed as lower forms of activity, superfluous, and not to be tolerated. Muscovites fell into a Manichean worldview, under which anyone who was not a member of the Orthodox faith was impure, an enemy and not to be trusted. This included, of course, all Westerners. It is this view which bred the arrogance and condescension shown towards foreigners at the tsar’s court that was remarked upon by so many foreign visitors and eventually led to the establishment of a separate quarter for foreigners outside Moscow. It also led to censorship to prevent wrong thinking, discouragement of free intellectual activity, and the banning of things foreign. These attitudes re-emerged during the Soviet period.

A final aspect of Muscovite Orthodoxy was that its prophetic and apocalyptic quality, focusing on the messianic role of the Orthodox nation and cosmic redemption, downplayed the role and importance of the individual, even his own salvation. Individual souls needed only to purify themselves and prepare for the Second Coming of Christ, which was seen as a collective, national event. No well-developed notion of individual conduct, rights, and duties ever emerged. Morality was not paramount and no moral code developed. People were politically and economically passive, behaved slavishly and were prone to exploitation, and had little incentive to develop knowledge or their abilities. Correspondingly, Moscow’s rulers treated people as masses and expendable fodder without legal rights.

Since the end of the Orthodox calendar, and therefore, according to many of the devout, the end of history, was to be in 1492, people began to expect and look for either good or bad signs, of the Second Coming or of the Antichrist.14 As that date approached, various cranks and mystics prophesied the end of the world. Though Muscovy survived 1492, this apocalyptic outlook persisted and rose to particular prominence during crises such as the Time of Troubles (1598–1613) and the Great Schism (1653–67). It also enabled Peter the Great’s opponents to label him the Antichrist and Petersburg a cursed city.

Under Ivan IV, the Terrible, the Russian calendar was reconstituted and history proceeded anew. His reign (1533–84) began with certain steps towards a secular state, but ultimately it marked the apex of Muscovite autocracy operating in tandem with the Church. As there were no ready models for law and governance (the Novgorodian model being considered unacceptable) or classical political knowledge, governmental (and Church) administration was indeed muddled, and legal codes and rational procedures were lacking. In order to decide how to remedy the problem, in 1550 Ivan convened the first zemskii sobor, a representative gathering of important personages of the realm to codify laws and carry out reforms. The primary result was a new legal code, the Sudebnik of 1550. Ivan restored some ecclesiastical lands to his domain and curbed the Church’s acquisition of new lands. He initiated military reforms and established detailed regulations for military service of the nobility, as a result of which the votchina system of landholding, already in decline, disappeared, and it became impossible to be a landlord without owing service to the tsar. In effect, nobles became glorified serfs with no contractual or legal rights to counterbalance the tsar’s power. Ivan purged the boyars and the Church, creating for seven years a virtual state within the state, the infamous oprichnina. He arrested and executed the Metropolitan of Moscow, subordinating the Church to princely power in fact if not in theory. His rule presaged the totalitarian state, complete with denunciations, interrogations, prisons, and terror.

It would be mistaken to view Ivan as simply another monarch creating a secular monarchist state at the expense of religion and the nobility on the Western European model. Rather, Ivan achieved his ends while embracing and even sincerely seeking to preserve Muscovite religious tradition. He never viewed himself merely as a political leader but, consistent with the old Muscovite ideology, as the anointed head of a monolithic religious civilization. He issued a 27,000-page church code and encyclopedia called the Hundred Chapters to codify prior Orthodox rules, traditions, and practices, and catalogue church history, readings, and the lives of saints, even while it formally purged material from Church tradition considered undesirable; it also tightened restrictions on secular art and music. Even a printing press set up in Moscow was declared an inappropriate method for reproducing copies of the Bible, and it was destroyed by a mob. Ivan also had his confessor, Sylvester, prepare a guidebook for private life called the Domostroi (‘Household Manual’),15 which prescribed forms and methods of dress, household economy, family relations, and overall behaviour, even regulating how to beat one’s wife (lovingly), preserve mushrooms, care for animals, spit, and blow one’s nose. It promoted a near-monastic, passive religious life, and demoted women. The more enlightened customs of Novgorod and Kiev were disapproved, ignored, or simply lost.

During Ivan’s reign, Muscovy was constantly at war with the increasingly large and sophisticated armies of Poland, Sweden, and Turkey. Ivan needed Western assistance in training and commanding his forces, as well as to help in developing industry and certain sciences such as medicine. This he sought mainly from England and Holland, Protestant countries to the west of his adversaries. In return, these countries received trade privileges which led to an increase in the number of foreigners in Russia. In 1558 Ivan started the Livonian* War against Protestant Sweden and Catholic Poland in an effort to gain access to the Baltic. After initial successes, this quarter-century effort ended in defeat and a net loss of territory, mainly due to the backwardness of Muscovy’s army. Muscovy was now enmeshed in military, religious, and cultural conflict with the West, but its political, military, and economic institutions and its people were unprepared to cope with the challenge. In the short term, the struggle caused further antagonism to Latin civilization and the termination of meaningful civilizing contacts with the West until Peter the Great. When a century later Peter the Great waged another major war against Sweden for access to the Baltic, Russia won due to Peter’s military and other reforms. In the victory parade held in Moscow, people carried portraits of both Ivan IV and Peter with the slogan ‘Ivan began, and Peter completed’.