Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

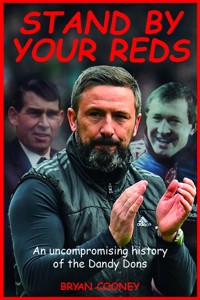

Stand By Your Reds, written by award-winning sports journalist Bryan Cooney, takes readers to locations where few have ventured – notably, the sacrosanct dressing room and those secretive corridors of power. This engaging narrative, built from a chronology of forensic interviews, ranges from the fifties to the present and tells the stories of an idiosyncratic team and an inveterate fan. Although it never neglects the triumphs, it refuses to ignore the turbulences. Cooney features: The incendiary reign of Eddie Turnbull, manager, martinet Stuart Kennedy – the first player to front up Furious Fergie Why Jim Bett was unable to forgive the directors Steve Paterson makes an extraordinary drinking debut Leigh Griffiths – why he was the one who got away The loneliest, most intimidating sacking of Milne's life and McInnes reveals what makes him really see red. Stand Free. Stand By Your Reds. Enjoy.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 634

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

BRYAN COONEY began his journalistic life on the Press & Journal in 1963. As a racing sub-editor and tipster taking the pseudonym of The Colonel, he won the 1965 Sporting Chronicle naps table. Fleet Street and a post as a sports sub-editor on the Daily Mail beckoned. He was appointed as The Scottish Sun’s chief sports writer in 1974, but an eventful lifestyle ended this association 17 months later. He worked on oil barges and selling penny insurance policies, and then joined the Daily Express. He went on to become Chief Sports Writer of the Daily Star, before being head hunted by the Scottish Daily Mail as Sports Editor in 1995. He was appointed Head of Sport of the Mail in London two years later.

He has written five books, won three Scottish Sports Writer of the Year awards, has covered three World Cups and myriad Wimbledons and Open Championships, presented several sports series for BBC Radio Scotland (picking up a Sony bronze) and for the celebrated BBC Radio 4’s Archive Hour. Now retired, he lives with his wife of 42 years in Glasgow. He has been an Aberdeen fan all his life.

First published 2017

ISBN: 978-1-912147-13-7

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emission manner from renewable forests.

Printed and bound by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham

Typeset in 11 point Sabon by Lapiz

© Bryan Cooney 2017

Contents

Prologue

CHAPTER 1: A Plot by the Old Firm?

CHAPTER 2: Ally, the ultimate warrior

CHAPTER 3: You’re in Eddie’s Army now

CHAPTER 4: Willie Boy Was Here

CHAPTER 5: A Template for Arsenal

CHAPTER 6: The Blast Furnace

CHAPTER 7: Gothenburg’s Other Face

CHAPTER 8: Super Trooper Cooper

CHAPTER 9: Crying Like a Baby

CHAPTER 10: The War Zone

CHAPTER 11: The ‘Joey Barton’ Influence

CHAPTER 12: Close up with Smokin’ Ebbe

CHAPTER 13: David Ginola: Sacre Bleu!

CHAPTER 14: The Rollercoaster Man

CHAPTER 15: From Hero to Zero

CHAPTER 16: The Whiskering of Joe Harper

CHAPTER 17: No More Good Cop

CHAPTER 18: Griffiths No More

CHAPTER 19: The scout wants a Jag!

CHAPTER 20: The Boogie Man Cometh

CHAPTER 21: Milne and Fergie Mk II

CHAPTER 22: McInnes Bites Back

Epilogue

Prologue

IDEALLY, PESSIMISM SHOULD NOT have a place in the lexicon of football. Yet, today, during the preliminaries at the Betfred Scottish League Cup final, negativity is overriding every other emotion. I mean, I’m wondering whether Aberdeen can beat Celtic, and the inescapable conclusion, derived from recent history, is that there’s more chance of Colombia being declared a drug-free zone. I’ve just seen the Dons team sheet and winced: there’s nothing in the line-up that suggests aggression, or even a desire to attack; players seem to be out of their positional comfort zones.

Off the pitch, it’s a different matter altogether. Here, on Sunday 27 November 2016, I find myself in the middle of a flag day extraordinaire. Twenty-two thousand Dons fans have been presented with either red flags or white flags. Some admirable souls have spent hours the previous day ensuring that there will be an awesome display. And now, 15 minutes before the scheduled 3pm kick off, people unfurl those flags and start waving them, frenziedly, above their heads. I join in. Hey, you don’t look particularly cool waving a flag, but I’m 72 years of age and cool belongs to another lifetime. The extravaganza endures for another 15 minutes and is an awesome flourish of faith and solidarity, one that so far has been unanswered over on the other side of the ground. Before they finally get their acts together, the Celtic brigades seem to be staring, awestruck, at the guys they love to denigrate as sheep shaggers. Well, we are certainly ahead in terms of these terracing mind games. But what will happen when the real spectacle begins?

My mind drifts back a couple of years, where we found ourselves in a similar Cup final situation, this time against Inverness CT. I wrote about it in the Cooney and Black blog…

The ascent to Area 410, Row N, Seat 12 of Celtic Park’s North stand upper might have been acceptable to a man possessing not only the lung power of a Chris Bonington but also his mountaineering pedigree. This old fella, without having the benefit of either, was consequently looking for an oxygen tent only a couple of minutes into the climb. The compensatory factor was reaching the summit and finding himself besieged by a red and white bedlam. Two important points were proved. Firstly, 43,000 Aberdeen fans, 150 miles from home, were demonstrating that if Scottish football is close to self immolation, then the potential North East obituarists have yet to be notified. And secondly, joy of joy, those roistering, raucous, rambunctious fans seemed intent on ridiculing the indictment that they suffer badly from inhibition and are dedicated rustlers of sweetie papers. Hey, legendary producer Phil Spector once nurtured what was described as the Wall of Sound, an impenetrable, multi-layered onslaught of orchestra-inspired music to monopolise the senses and the pop charts in the early ’60s. He should have been in the East End of Glasgow on Sunday afternoon to record something that came very close to his concept of noise. This was one that steamrollered the senses and made you inordinately proud to be an Aberdonian.

Now, I have pursued the fortunes of this wildly idiosyncratic team for 65 years, most times fanatically, occasionally almost apologetically. I have never heard anything like this before – even on a night of Pittodrie mayhem which I shall return to in due course. Suddenly, all supporter sacrifice made sense. The myriad tears, disappointments and disaffections were forgiven if not forgotten. And this, you should note, was before the League Cup final between the Dons and Inverness CT had even begun.

But let’s go back to those 65+ years: if this promised to be an occasion for nostalgia, I determined to indulge myself. I remembered the 1949 day my dad took me to Pittodrie for the first time. Soon, he was wishing he hadn’t troubled himself. How do you constrict the conduct of a venturesome four-year-old who was fascinated by everything aside from the football? The denouement came when I heard Dad complaining about someone fiddling. I began looking around, perhaps expecting to see a string quartet in the immediate vicinity. My father became agitated, possibly because of the home team’s shortcomings, most probably because of my finite attention span, and he signalled he’d had enough. He grabbed my hand and marched me down the stairs of the main stand. As far as I know, he never called in at Pittodrie again.

But sometimes it takes only one visit to be infected with the football virus. And so, within three years, I became a Pittodrie regular. I began to identify my own heroes and there was not a fiddler among them. Their names adorned my autograph book: Archie Glen, Jackie Hather, of the double shuffle, Paddy Buckley, Harry Yorston and ultimately Graham Leggat. They won the First Division championship in 1954-55 with a manager called Dave Halliday. They added a League Cup victory a year later with a new man: Davie Shaw. There was victory on the pitch and spoils on the terracing. My entrepreneurial instincts were satisfied: I’d wait for the crowd to disperse and then collect the beer bottles in a carrier bag. I’d swap them for a couple of shillings in the licensed grocer’s in Merkland Road. Perhaps I’d been blessed with foresight – my dear brother John eventually bought that shop in the late sixties.

Paradoxically, in spite of this success, we were destined to occupy the football boondocks for more years than I care to remember. This was no deterrent to a few young men from Aberdeen Academy who were willing to accept equal dosages of rough and smooth. Guys like Ivor Finnie, Gordon Donald, John Dingwall and I decided to join the official supporters’ club, which comprised a handful of men from another generation and a couple of highly emancipated women. The chairman, a lovely yet intensely garrulous guy, had a serious speech impediment and if you were in the front row at a meeting, you had to duck, bob and weave, like a professional boxer, to avoid taking direct hits from his saliva. You required dedication to be in our small gang. Think of today’s Red Army and its impressive infiltration of away ends. Ours didn’t even constitute a platoon as it made its way all over Scotland, kitted out in red and white caps and scarves. We even bought ourselves blazers and badges at a later, more sophisticated, date.

Campbell’s, of Bon Accord Square, provided our transport and, normally, one bus was sufficient for our needs. Our travels were not without incident, however: we left Ibrox one year with a hail of stones bouncing off the framework of the bus; we retreated from Kirkcaldy severely depleted of our numbers. We invaded the pitch when a Cup defeat proved unacceptable; the local police were unforgiving. On another Cup adventure, this time under the managerial custody of Eddie Turnbull, we took a respectable following to Easter Road, and only a last-minute equaliser secured us a replay at Pittodrie. By now, I was working in the Press & Journal editorial but was granted a night off. I squeezed myself into the Merkland Road end as 44,000 rolled up that Wednesday evening. The crowd groaned collectively as it was announced that the pugnacious Ernie Winchester would be playing: in some quarters, he was slightly less popular than a visit from the bailiffs. Those sceptics changed their minds, temporarily, at least, when he scored twice. Winchester, who died last year, was an inspiration, but not as far as Hibs centre half John Madsen was concerned.

He later informed anyone who would listen, ‘Tonight I met a madman!’

But pay attention, if you will, to that figure of 44,000 on a hysterical night in March of 1967. It brings me back to the hysteria of Sunday and the pretty surreal fact that 43,000 of my ain folk had converged on Glasgow to ostensibly take over the city. Was it all worthwhile? Not, perhaps, in my highly critical book. The football game began, but to call it a game is taking a liberty with the English language. Thankfully, as far as this person was concerned, it was over fairly quickly, not of course before Jonny Hayes had been carted off to hospital, nails had been gnawed to the quick and penalties had been missed (by Inverness) and converted (by our lot). We won, but it was a victory that delivered little in terms of satisfaction. Still, as we prepared to leave Celtic Park, my eyes were drawn to the seats immediately in front of us and a little boy clad, like his father, in red. He was bright-eyed and pumped full of mischief, sticking his tongue out at anyone who looked his way. It was pretty obvious that it was of very little concern to him what was going on down on the pitch. Considering the paucity of the play, he could have been forgiven. Perhaps this was his first football match. His initiation. Perhaps he was looking for a fiddler in the stand, just to remove the edge from the boredom. There again, maybe, just maybe, he’d caught the virus that makes professional football so compulsory – the one that infected me 65 years ago. I wondered whether he’d still be supporting his team in the year 2079.

We’re right up to date and, unfortunately, back at Hampden. The pessimism – maybe prescience is a better word – has been justified. The players are disporting themselves in a manner that might suggest their rectal hairs have been tied together. Their performance is abysmal, going on abject, and they look petrified of Celtic’s presence. They have a semblance of an excuse, of course. The fans are becoming restless: they are targeting their natural victim. Why has the manager put a right-footed player, aka Anthony O’Connor, as left-side centre back? Why has the manager placed the faithful servant Andrew Considine in a situation (left back) that illustrates his weaknesses? Why is Graeme Shinnie being persevered with in midfield and not his natural niche of full back? Why is James Maddison, a welcome and intuitive loanee from Norwich, playing ostensibly on the left wing and not in central midfield? There are no answers to these questions because Derek McInnes is someone who allegedly has an abhorrence of justifying himself.

This is the same manager who declared himself satisfied with his squad back at the end of the 2016 summer transfer window when it was apparent, to anyone barring the myopic, that he required two robust players to stiffen the centre of defence and midfield. Anyway, the goals go in – one, two three – and once again we are occupying the roles of the oppressed. Why are we giving Celtic such space? Why are we standing off them as if we are David Attenborough’s cameramen and they (Celtic) are a rarefied species? I have had enough humiliation around the three-quarter-time mark. Yet there are vestiges of guilt as I file out of Hampden, in the manner of a carpetbagger who has been denounced. Still, the paying customer is invariably right. Being short-changed in this life demands a response. Mine is a silent protest. Well, perhaps a few profanities short of silent. As for those players, well, the thing is if you come to Glasgow and occupy the roles of frightened sheep, then you’re going to get a spanking. Jesus! It all started so well with those flags. But, am I surprised by another anti-climactic event in the history of Aberdeen FC? Of course I’m not. In some ways I’m inured to disappointment. Supporting and writing about Aberdeen FC over seven decades prepares you for anything that the Good Lord can fling at you.

But enough of the present. We’ll return there soon enough. It’s time to explore those idiosyncrasies of the past. There will be no over-concentration on facts, figures and games played. This book will be more about personalities, significant flashpoints and ‘inside’ stories. Let’s start on a positive note with a closer look at the team that cantered through the serried ranks of Scotland’s finest football teams in the 1950s. It was a time when Aberdeen FC were feared by everyone.

CHAPTER 1

A Plot by the Old Firm?

IN SOME WAYS, THE REASON FOR Aberdeen’s inexorable rise to the pinnacle of Scottish football in the mid-1950s can be laid at the educated feet of two men: Paddy Buckley, from Leith, Edinburgh, and local lad Harry Yorston. Scoring goals represented no problem to them, but there was a problem for all that. A major one which we shall come to presently. They were contrasting units in style, if not in height. Buckley, a 5ft 6in centre forward, was a veritable flying machine. Over the vital first five to ten yards, it was as if someone had applied a blowtorch to his backside, and that searing pace took him past opponents and on to confront chittering goalkeepers. His Pittodrie goal ratio, much the same as that at his previous club, St Johnstone, was to be located at the top end of the market: 92 goals in 153 matches.

Yorston, half an inch taller, blond and handsome and given the somewhat challenging sobriquet of ‘golden boy’, operated in the W-formation of a five-man forward line and therefore further back at inside right. He didn’t belong to the streamlined class as far as speed was concerned, but there were compensatory factors. Most of the time, his spirit belonged to the never-say-die society and the way he worked ensured that his socks were ritually discarded. Equally impressive was his appetite for goals. Owing to the absence of official records burned in the Pittodrie grandstand fire of 1971, there are two quite different versions of that appetite. On the player’s personal page in Wikipedia, he is said to have scored 98 goals in 201 outings. But the same organisation, on its Aberdeen FC page, stipulates that he accumulated 278 appearances and hit the sweet spot 141 times. The one certainty is that he derived considerable pleasure from scoring goals, something that today’s contemporaries would do well to digest and indeed work on. Sometimes, in current matches at Pittodrie, a spectator can count himself lucky if he sees two or three shots of worthwhile calibre in 90 minutes from the home brigade. Yet, they play with a ball that is so light it almost begs to be blootered. In contrast, away back when, they were playing with what might be considered an alternative to the medicine ball – a ball that, when saturated with rainwater, could test the durable properties of your ankle ligaments if you were unlucky enough to mis-kick it.

In terms of scoring, then, there was little to separate Buckley and Yorston when, in 1955, Aberdeen won the Scottish First Division title for the first time. And, yet, in the eyes of the paying public, or at least more than a few members of this fraternity, they were leagues apart in delivery of satisfaction. Buckley, who joined the club in 1952, was simply incapable of misconduct in the fans’ books. Former colleague Bobby Wishart illustrates that statement:

‘There was a funny incident with him at Inverurie one night. He was guest of honour at some function and, while he was sitting on the platform, he fell asleep. When he woke up, he was somewhat disoriented and didn’t realise there was a microphone near him. He said something like, “I suppose I’ll have to thank these bastards!” Would you believe, the crowd just burst out laughing? And, for some reason, there was a never a squeak of that back in town. Can you imagine what would have happened if that had been today? You cannae get away with anything these days.’

So, you would be borrowing from hyperbole only slightly if you said Buckley’s popularity with everybody concerned was such that he might have careered up Union Street, buck naked, and received no more than a token admonishment from either the constabulary or indeed the magistrates.

With Yorston, it was radically different. You suspect this player – he had been at Pittodrie since 1947 and established himself as a first-team regular a year later – would not have been so fortunate had he embarked on a similar escapade. It seemed that, on the Pittodrie playing surface, he was only a footfall away from reprimand and the derision of hundreds, if not thousands. Whatever, this attitude eventually helped him make the decision to forfeit the putative glamour of football and plunge himself into a far more exacting existence: he retired at the age of 28 and, following his father’s lead, spent a portion of his working life as a porter, hefting stinking boxes at the fish market. The Dons, in turmoil due to his decision and other defections, disappeared into a tailspin. But, returning to my theme: what, do you imagine, affected the dichotomy between the two men? Why did the crowd generally favour one and frown on the other, particularly when they were delivering proportionate parcels of aid and assistance to the team?

The answer, or more correctly, one rather controversial interpretation of the answer, comes from Wishart. The latter became a vital member of the championship winning team of 1954-55. He was to be found at the second base of the W formation, at inside left. Even more helpful, for this particular narrative, he became Harry’s pal. He was also on good terms with Buckley. Now in his 84th year, Wishart’s insights into events that occurred 60 years ago are as sharp as they are revealing:

‘The fact was that half the crowd loved Harry, the other half hated him,’ he recalls. ‘He had that sense of humour that some people understood, while others thought he was big headed. Sometimes, maybe something he said in the newspapers was misinterpreted. In Aberdeen, anything happening through the football went round the city like a bush fire. The bigger the scandal, the quicker it went round. There was only one team to concentrate on. I always had the feeling that a lot of people came up to work in Aberdeen but weren’t Aberdeen supporters. You’d get Rangers and Celtic guys who worked in the city and went to Pittodrie for their football. A lot of the stuff went on – players getting picked on and barracked – but I don’t think they were the true Dons fans. I think they were Old Firm people who didn’t want Aberdeen to win. And, indeed, I think over the years these fans kinda got Harry down.’

Even today, the reason behind Yorston’s defection to harbour life has never been made public. Certainly, the constant carping seemed to occasionally deflate and discombobulate Yorston, not that he was a man for appending his angst to sandwich boards and parading them in the city. Was it, as Wishart suggests, a covert, terracing-inspired Old Firm conspiracy? If so, it was a devious tactic that eventually paid a handsome dividend for the critics. There again, was the genesis of it all far more simplistic? Was envy the main player here? There is, after all, repeated evidence in football of local lads being unable to satisfy the standards set by their own townspeople. Friendship or not, Yorston did not reveal his inner thoughts on the issue even to his closest colleague. Wishart remembers a deep, sometimes impenetrable, often paradoxical guy who thought about the game of football far more than most of his contemporaries. But, if he was not more forthcoming about his personal problems, he was pleased to fulfil the role of mentor.

When Wishart had performed well in one game and perhaps indicated that he had arrived as a player, Yorston cautioned him against believing that this guaranteed a long-term future. His advice was far more prosaic but weighted with wisdom: wait for three months and see if the crowd’s attitude remained the same.

‘He was an old soldier,’ is the Wishart assessment. Indeed, an old soldier in so many respects. On the day of a pre-season trial, when the first team took on the reserves, Yorston told Wishart that a trip to the hairdresser’s was an imperative. The younger man protested that he’d had a haircut two weeks previously. Yorston insisted that having a trim made a man look his best. ‘And when the crowd see me tonight, they’ll say, “See Yorston, he’s looking younger than ever!”’

Yorston was an enthusiast of the tricks of the football trade long before they became fashionable. And his young protégé learned quickly:

‘I’d weigh up the running ball and if I didn’t think I could catch it, I let it go out of play. Harry didn’t advocate taking things so easy. “That’s not the way to do it,” he’d say. “You knock your pan in trying to catch it, even although you know you’ll not succeed. Then you get up, having just failed in your mission, and you spring back to your position, then wait for the goalkeeper’s kick. The fans will say, “Christ! Look at Yorston – he can’t wait to get back into the game again.” These were the wee touches that Harry had. What he said was right: it could put a fine polish on things.’

But, of course, if the theory sounded perfect, the practice occasionally was blighted by imperfection. Yorston could be happy go lucky at times and, added to that, he had a smile that could outperform the sun. Some folk, suspicious folk in the Granite City, felt that he occasionally disappeared into a mood of indifference – and rushed to an inevitable conclusion: ‘See that Yorston, he’s no botherin’ himself, he couldna care less.’ This was in contrast to Buckley, Wishart insists. ‘Paddy could get away with smiling when he missed an open goal. He was forever shrugging and putting his hands up to the crowd. Harry simply couldn’t get away with that.’

On the field of play, Buckley did not look for hiding places, yet, off it, he seemed to favour the abrogation of responsibility. Wishart’s still handsome features form a smile. ‘I remember Paddy got a contract for the Daily Express while we were on tour in Canada and America, and they (the Express) were one of the better payers. Aberdeen Journals, in contrast, weren’t good payers and I was writing for them all year round. Mind you, I think they gave me a little bit extra for sending stuff from Canada. Anyway, the upshot was I wrote Paddy’s articles for him as well. He picked up the cheques and I did the donkey work.’

Wishart appears reluctant to adjudicate on Buckley’s writing skills, but adds, significantly, ‘Some lads didn’t seem to know what was acceptable and what wasn’t. I remember there was an article one of the guys wrote. The headline was: Does a Manager Manage? They (the directors) stopped all the journalism (from players) after that – and probably quite rightly. I mean, you cannae come away with stuff like that and not upset either the manager or the directors. But, anyway, Paddy was a bright little fella. When we were coming back from games, we used to play solo whist – Alec Young, Archie Glen, Paddy and myself. I would say Paddy was the best player of the four. Remember, Archie was a B.Sc and all. But Paddy was streetwise.’ Wishart might have added: most of the time. ‘You know, after games, he and I used to go for a drink at the Royal Hotel, for it was the quietest place in Aberdeen at the time. He wasn’t a big drinker, but he was a guy who never looked sober after a couple of pints. He always loosened his tie and took his false teeth out – and his hair fell down like bead curtains on both sides of his face. He could look dishevelled in no time at all and always seemed half-canned. But, put him on a football field and the fans really liked him; he never stopped trying, he chased everything and gave 110 per cent.’

Yorston, in contrast, found that Pittodrie was a forbidding place even in the early fifties as people were still attempting to clear the dust and smell of World War II from their throats. He therefore enjoyed life more on his days off. The ladies were attracted to his chiselled features. Wishart recalls, ‘When he went to the local Palais in Diamond Street, he would tell his dance partner not to stand on his toes, or kick his shins, because he reckoned those feet were worth £25,000 each. He would make the ladies smile. So, yes, he was a great guy – but he also was a great gambler. He’d gamble on all sorts – horses, mainly, and the dogs at Garthdee, You couldn’t really gamble on football at that time – it was frowned upon – but he was a student of gambling. He used to have a notebook full of all the dog tracks in Britain, complete with the numbers (traps) that won. He was forever looking for a system – I don’t know if he ever got one.

‘But the laugh of the thing was that I used to tell him that he should pack it up: that it was a mug’s game. I never had a flutter, but I was a smoker. He replied, “Well, look at you – you use fags and they just go up in smoke. Meanwhile, I spend money on dogs and horses and I might get a return some time.” And years later he won, I think it was £175,000, on the pools, so I said to him, “You were right after all, and I was wrong.” That was after he stopped playing for Aberdeen.’

Yorston, who disappeared into the less demanding reaches of Highland League football, took a more understandable decision when he received that massive windfall in 1972: he quit the stench of the fish market and began to ingest the more attractive aroma of pound notes. It is only fit and proper, at this juncture, that we concentrate, more on the man who is contributing to the composition of this opening chapter.

Wishart was a notable donor to the Dandies’ cause from 1953 to 1961, before he finally decamped, most probably disillusioned, to near neighbours Dundee. There, he helped the Dappers win the title a year later. He initially stepped into Pittodrie on a bright August day in 1951. His was what might be considered a whirlwind signing. He’d played only two trial games, one against Celtic at Parkhead, the second against Brechin. Wishart turned out at outside left in the second match and remembers doing nothing of any great account in a no-scoring draw. ‘I didn’t score and I didn’t make a goal.’ Yet director John Robbie was at the game and saw something beyond the obvious, and so plans were hastily drawn up to make the 18-year-old an instant Don.

Aberdeen, allegedly the highest-paying club in Britain at the time (£14 per week, with a £2 win bonus: this rose incrementally to £20 a week, plus bonuses, over the years), did some things in style. They travelled first class on the train and accommodated players in grand hotels. The young Wishart and his dad were put up at the Caledonian, in Union Terrace, before signing. They were impressed. A cursory inspection of the Pittodrie dressing room impressed him even more, but caused him to wonder whether he had taken the right decision. He discovered a football club almost bloated by icons and legends, some of them old enough be his father: Jimmy Delaney, Tommy Pearson, Gentleman George Hamilton, Tommy Bogan, Pat McKenna, Don Emery, Archie Baird; and then a host of others: Hughie Hay, George Kelly, Yorston, Joe O’Neill, to name but four. ‘They had that many players,’ he remembers. ‘And there were not many bad ones. At that time, they had virtually three guys for each position, including inside forwards and left wingers in abundance.’ There had been a plan to field a third team in the Highland League, but this had failed to materialise. Where was he going to fit in to what was an overcrowded situation?

The solution was provided with an almost immediate call-up to National Service. Wishart was sent to Ireland and subsequently played with Portadown, who turned him into a scoring centre forward. ‘I was a nobody with no reputation, a wee guy coming in from nowhere. If it hadn’t been for National Service, I don’t think I’d have made the grade at all.’ Back in the North East of Scotland, the nobody had altered the script: now he was a seasoned player with a reputation. He found everything had changed. The Dad’s Army brigade had been ‘demobbed’ – with the greatest of respect, you imagine – and there was an infusion of new blood. There were changes, too, other than personnel. ‘Originally, there had been no equipment at all. The cure for all injuries was a hot cloth. Hey, you weren’t surprised that no-one was injured in those days, for the treatment was worse than the injury. But now they brought in this machine that you could give you infra-red and ultra violet rays. The latter was most popular because the guys could not wait to get under it to get a sun tan.’

Football occupied an alternative planet back then as opposed to now. The riches, the baubles and fashion statements, upon which today’s players seem to place so much emphasis, scarcely existed. ‘There were only three or four guys at Pittodrie who had a car – and I’m talking about when we were winning the championship. George Hamilton had one, so did Harry, Jackie Hather and Jimmy Mitchell. I didn’t. I always looked upon it as a waste of money. I lived right in the middle of town and could walk anywhere. Most people travelled by bus. And it all meant that you were consequently in touch with your public. You couldn’t avoid them, as you were sitting next to folk on the bus. It wasn’t the glamorous occupation that it is now.’

Wishart wanted more than fancy wheels and a bronzed countenance; he sought a speedy graduation into the first team. He had two things in his favour. First, Davie Shaw, who had gone from player to coach in 1953, spent a lot of time educating the young players: ‘In those days, the manager managed from his office, and the coach or trainer was the guy who tried to help you with your game. Shaw was of great assistance to me.’ Second, Wishart was a clever passer and, allied to this, possessed a shot that could blister goalkeepers’ fingers. Essential to the force was a short back-lift which didn’t offer goalies a sporting chance of spotting from whence the danger was coming.

So let’s return to Wishart’s assertion that managers managed from their offices. What of the Dons leader? David Halliday was familiar with the contours of a football pitch: as a player for Dundee, Sunderland, Arsenal and Manchester City, he had scored a phenomenal 303 goals in 396 matches. The scoring flamboyance did not translate to his job as manager, however. He appears to have been the ostensibly silent type. Yet the silence was effective. Since his arrival from the quaintly-entitled Yeovil and Petters United, he had piloted Aberdeen to a win over Rangers in the Scottish League Cup in 1945-46 (prior to its recognition as a fully-fledged competition) and lifted the Scottish Cup in 1947. And, of course, he would be charge in the halcyon days of 1955. But what of him as a man? Wishart recalls, ‘He wasn’t the kind of manager or coach you have nowadays who works with the players every day. He appeared on a Tuesday for the practice match between the first team and the reserves. He would stand at the tunnel, watching from afar. He hadn’t a tracksuit on; he wore a suit and, no, he wasn’t a snappy dresser. He didn’t shout or pass comments, he just observed. On Saturdays he was there to give team talks. Really, he was the kind of fella you never got to know because you weren’t in touch with him. I remember one day I was dropped and I went to see him to register my disquiet. He told me simply, “Bobby, you were in my team” (an indication that the directors interfered). I wasn’t surprised, mind you. But, hey, even suppose he had picked the team, what a good get-out! I mean, you went in there, pretty annoyed, and thinking you had something to impart, but you were immediately deflated with what he was saying. And he was saying, “I think you’re a good player and you should have been playing, but…” You landed back in the passageway without really saying very much at all.’

The time is appropriate to inspect the board of directors who, if you swallow the Halliday line, were intent on sticking their fingers in the playing pie. At that time, Willie Mitchell, the managing director of a licensed grocer’s, was the chairman. His deputy was Charlie Forbes, a rather austere schoolteacher. Dick Donald, who had played for the Dons for five years before the War, brought a bit of warmth to their directorial number, and John Robbie perhaps a sprinkling of notoriety. Apart from being vital to Wishart’s signature, he was the SFA man who had Rangers stalwart Willie Woodburn placed in the sine die cell in 1954: the offence? A head butt on a Stirling Albion player. ‘Those directors were very much aloof,’ says Wishart. ‘We always travelled first class, but they were in their own compartment, so you never spoke to them. They didn’t come in the dressing room, apart from Dick Donald, who’d appear before games and wish you well. No, you were very much left to your own devices; you were the player, you knew what you had to do, so you just had to get out there and do it. You also knew your place. It was very much a case of the Upstairs, Downstairs syndrome. At Dundee, Bob Shankly used to talk of ‘Them Upstairs’ as a necessary evil. But the other thing was that you never knew what was going on in the world of football, because no-one told you anything. You read in the newspaper that Leeds United were interested in you, or Chelsea. This all happened to me. In fact, Newcastle United came up and made a £25,000 offer for me, but I never even got consulted or told. But I knew first hand because I had been semi tapped. A guy who was very friendly with the manager, Stan Seymour, asked me if I would be interested in going down there.’

Wishart, possibly remembering how he’d failed to achieve a result in the manager’s office, ignored any temptation to reprise the situation: ‘Besides, it didn’t bother you much because you knew that you were playing for the highest paying club in Britain.’

No-one at that time, it should be pointed out, dared take liberties with Aberdeen. Alex Young, nicknamed ‘The Golden Vision’ by Hearts fans because of his sublime skills, later confided to Wishart that the Dons had become the most feared team in the land. And this, despite the fact that there were several seasoned outfits around at the time. Aside from the traditional contenders, Celtic and Rangers, people talked in awe of Hearts’ front three, Conn, Bauld and Wardhaugh. Hibs, meanwhile, were blessed with the Famous Five of Smith, Johnstone, Reilly, Turnbull and Ormond. Dundee, Clyde and St Mirren had good players. It was an exceptionally difficult league to win, then, far more so than today’s premiership. But, as a collective, Aberdeen proved superior to anyone that 1954-55 season and that made me inordinately proud. A pupil of Kittybrewster primary school, I believe I was probably more proficient at rhyming off the Aberdeen team than I was my mathematics tables: Martin; Mitchell, Caldwell; Allister, Young, Glen; Leggat, Yorston, Buckley, Wishart and Hather.

I could not wait for my weekly visit to the South terracing. Preferably, I was stationed against the perimeter stone wall and thus within touching distance of my heroes. Weekly? My loyalty was such that I attended reserve matches as well, watching young men like Jim Clunie, Ian McNeill and George Mulhall beginning to shape their careers. First-team affairs were the ultimate delight, of course. If I were late in arriving, having walked from my home in Hilton Drive and perhaps having lingered too long salivating over notable additions to my autograph book, the crowd would pick me up and hand me down over their serried, cloth-capped ranks until I reached the safety of that wall. Here, there was a temporary relief from the fug of cigarette smoke – smoking being a fashion that seemed to fascinate everyone back then.

The tannoy system – a prototype of today’s one that encourages you to ‘Come on you Reds’ – would spew out the popular music of the day. Trumpeter Eddie Calvert’s ‘Oh, Mein Papa’ was a particular favourite, sending chills scurrying down my spine. Then the teams would emerge to the accompaniment of the delightful ‘Bluebell Polka’ – a tune I practised with great gusto on my dad’s piano. The appreciation of the crowd sometimes obscured parts of the Jimmy Shand hit, but that was a small and acceptable negative. Then, with my preparation complete, it was match time: I owned a rattle (a product of my bottle-selling enterprise); I had a set of lungs to provide shrill support. Now it was up to those players to perform. But these were magical performers. I shut my eyes and can visualise them all now, particularly Graham Leggat sprinting in on goal from the right wing; Buckley stealing in like a whippet and making capital out of even bad passes; Hather introducing full backs to the innovative double-shuffle, a trick that inevitably left them floundering. Otherwise known as ‘The Hare’, Hather was the fastest man Wishart ever saw on a park, and yet he coupled speed with excellent ball control: ‘You know, I heard the odd comment about how he wasn’t the bravest winger they ever saw. But if they’d known that he was playing with one kidney. That was brave enough in itself, never mind the attentions of a couple of burly full backs. He was a very courageous wee fella.’

Aberdeen would need a generous helping of Hather’s courage if they were to win the title. They had done nothing to enhance their league status in 1953-54 when they finished a distant ninth, ten points behind winners Celtic. But they were beginning to warm up in other ways, appearing in the 1953 and 54 Scottish Cup finals. They were beaten in both, first by Rangers (1-0, after a 1-1 draw) and Celtic, by 2-1. That second final was when I truly formalised my relationship with Aberdeen FC and became a fan for life. The minutiae surrounding that match is deeply implanted in my memory.

I am positioned, for once not at the Pittodrie perimeter wall, but in the living room of my home in Hilton Drive. Excitement dictates that I cannot sit down, but prefer to pace, nervously, from wall to wall. I look out on a lovely front garden that might have been designed by Capability Brown, and see the tall figure of my father. He is a schoolteacher by profession, but a horticulturalist by nature. The HMV radio is turned on and hope courses through my heart because we won our semi-final in a canter, slaughtering the mighty Rangers, 6-0. Then comes a team announcement. Joe O’Neill, whom my brother Michael professes to know, scored a hat-trick in that Rangers game, but he had fractured his skull and is missing from the line-up. Jim Clunie, Aberdeen’s reserve centre half, suddenly finds himself in the alien position of inside left. I knew nothing of tactics in those days – perhaps I still don’t – but the metrological office in my head informs me that a storm is imminent. Alec Young gives confirmation of the bad news when he puts through his own goal in the 50th minute. But this is football and the course of a match can alter very quickly. And so it unfolds: the inimitable Paddy Buckley equalises within 60 seconds. If there are wild scenes of jubilation in a sizeable portion of the 130,000 crowd, there is commensurate chaos in that Aberdeen living room on that day of 24 April 1954.

I go ape, jumping around the room in a frenzy of delight. I can see my father’s face now. It is pressed hard against the front window. It’s a concerned face, one that doesn‘t have an answer to the present conundrum. He’s mouthing the words, ‘What’s wrong with you?’ I’m too busy screaming to deliver an effective response. He rushes into the house, possibly intent on calling the emergency services. But soon his fears are becalmed: I’m telling him that the only problem is to find a cure for sheer elation. He returns to his garden. I return to the inevitable. Celtic, through the capabilities of Sean Fallon, make it 2-1 and take the Scottish Cup back to Parkhead. The day ends in tears. Rivers of them. My father, horticulture over, is presented with another conundrum: the kid he took to Pittodrie a few years ago –the kid who did everything but concentrate on the football – has obviously formed a deep attachment with the club in a short time. He is only nine years old.

But if that match impacted on me, it possibly slaughtered Wishart. Somewhat inexplicably, he found himself 12th man that day. His old pal, Harry Yorston, was similarly overlooked. His recollection comes at the expenditure of pain. ‘They had the choice of two inside forwards, one very experienced in Harry, then myself, a natural in that position, left foot and all that. They gambled, took a chance. They had no need to do that. They must have had a rush of blood to their heads. I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t have been Davie Halliday that came up with that one. Anyway, I reckon that’s what lost them the game. Of course, I was a wee bit biased because I was sitting it out. Harry was out, too. That was the sad thing because Celtic weren’t really a force to be reckoned with at that particular time. You had more concerns with Rangers and Hibs. But it was unfortunate. I’ll put it that way.’

Wishart claims that this wasn’t a defensive tactic and that Clunie was out to fulfil the forward role. Big Jim, he says, did not pursue the style of conventional centre halves: he was a guy who could put his foot on the ball and look to direct it to someone in a more influential position. A John Stones prototype, if you like. Without the price tag, of course. ‘But there’s a big difference to being where you can see the ball coming to you, and playing a team with your back to the enemy. It’s a different concept altogether. Yes, there were two disconsolate guys that day. Harry and I were obviously hoping Aberdeen would win, but let’s say we were a bit disappointed that we couldn’t take part.’

Perhaps the lesson had been learned. Wishart and Hather were restored to the front line in the new season and Aberdeen began to put down their league marker so forcibly that the ground trembled. Four successive victories, over Stirling Albion, Dundee, Hibs and Motherwell gave them an impetus that they would rarely lose. Thirty-eight thousand fans subsequently came to Pittodrie to see if their heroes could eclipse the then current champions, Celtic. Unfortunately, they couldn’t, the Glasgow team recording a 2-0 win and their centre half, Jock Stein, attempting a new method of defending: ripping Buckley’s shorts from his backside. But this, the defeat, not the shorts shearing, was only a flaw on the radar screen: the Dons were soon returned to winning ways and their home form, in particular, removed the threat of Rangers and Hibs as authentic challengers. Rangers, in fact, were destroyed, 4-0, at Pittodrie, with a Buckley hat-trick and a typical Leggat counter delighting the home crowd. Aberdeen, requiring three points from their final three games, travelled down to Clyde in early April. A win would give them their first title in 52 years, provided Hearts did not leave Ibrox, their faces wreathed in smiles. An Archie Glen penalty gave the Dons victory. Over the city, Hearts were snarling rather than smiling. Defeat makes you snarl. Aberdeen were champions.

So, what changed from one season to the next? Why did a hitherto rather mercurial Dons side suddenly blossom into title winners? ‘Modesty prevents me from saying,’ a smiling Wishart recalls, ‘I hadn’t been playing in the team all that often but I came into the scheme of things in 54-55. That’s not the whole story, though, or even a fraction of it. One thing I remember is that we didn’t have many injuries. We were able to put the same team out week after week. And that helped a lot. That’s why you could rattle off the team because the team picked itself. And there were no subs. With the pool system nowadays, folk will not be remembering teams as such. Another thing: we also had a very good home record.’

The celebrations that night were confined to a few bottles of champagne and a homecoming at Aberdeen’s Joint Station that was somewhat low on fervour. Estimates differ as to the number of fans that greeted them, but it’s probably safe to say it was anything between ten and 30. But were those fans who didn’t attend simply acknowledging, if only subliminally, that they were nearing the end of a delicious lollipop? Everything was about to change and, unfortunately, not for the better. Halliday was first to abscond. He took over at Leicester City after having allegedly being told by the parsimonious directorship that no advancement in his salary was imminent. But the parsimony had equally damaging tendrils. The players who had performed with such distinction asked the directors for more finance and, like latter-day Oliver Twists, were sent away as if they had been guilty of ingratitude. ‘Aberdeen stuck to the rule book,’ Wishart remembers, ‘In spite of their status as the highest paid club in Britain, they never paid over the odds.’

Discontent, owing to the short-sightedness of the Pittodrie board, proliferated among the playing staff. In spite of this disaffection, they managed to finish second to Rangers in the 1955-56 season and win the Scottish League Cup by beating St Mirren, this under the guidance of the newly-elevated Davie Shaw. The Aberdeen populace, possibly eager to atone for their embarrassing absence earlier that year, turned up in multitudes, and it’s said 15,000 formed the welcoming committee. But trouble is never far from the surface when money, or more appropriately, the lack of it, is concerned. In the close season of 1956, the team went on a whistle-stop tour of Canada (principally) and New York. They sailed up the St Lawrence River on The Empress of France. It has been described as a very good tour. ‘There wasn’t any skulduggery going on,’ Wishart claims. ‘But we had a lad looking after us from the Canadian Football Association. He was in charge of the purse strings.’ Presumably he had received a fiscal tutorial from the Aberdeen board of directors. ‘He came from Fraserburgh, and I can tell you we had a helluva job getting money out of him. I’ll never forget him.’

Neither would the Canadian press forget the new Aberdeen manager. Shaw was comfortable on the training pitch, but found it difficult to strike up an equally satisfactory relationship with sports reporters. They christened him Davie ‘No Comment’ Shaw. This, however, was only the beginning of the manager’s woes. The ship was anything but happy. Mutinous thoughts prevailed. Harry Yorston lobbed a grenade into the boardroom by retiring from football, aged 28. The punishment that had been inflicted on Buckley’s knees took its toll the same year. He went for a cartilage operation and it proved unsatisfactory. He retired. Age tapped on the respective shoulders of Alec Young and Jimmy Mitchell and both were released in 1958. Wishart reckons that both Fred Martin and Jackie Allister had their differences with Shaw. The influential Leggat departed for Fulham in 1958. It’s as if a wrecking ball had been at work. Pittodrie became a demolition site. ‘Apart from Fred Martin and Davie Caldwell,’ he remembers, ‘we were left with the left-wing triangle of Glen, Hather and I. The side just disintegrated and we didn’t have the good, experienced reserves because we had sold most of them. Jackie Allister was a volatile kind of guy and I think Davie felt he wasn’t going to fit in with his plans – that maybe he would be difficult to control. They fell out and we’d lost another good player. So, by the time we got to 1959, we were left with only five of the title-winning squad. By some freak – the draw favoured us greatly – we went to the Cup Final that year, only to lose 3-1 to St Mirren.’

League form had slipped ominously by then: sixth place in 56-57; 13th in 57-58; a similar performance in 58-59. The stench of disaster was in the air for a team now replete with pale imitations of the legendary figures of old. Was Shaw capable of leading the fumigation squad? Sadly, the answer was in the negative. Luckily for Shaw, however, there was no firing squad: Aberdeen, until recent times, have never been associated with sacking managers. Tommy Pearson, a former stalwart, came in as boss despite flourishing a curricula vitae that contained this alarming message: NPE – No Previous Experience. Shaw moved back to his role as trainer. Would Aberdeen pull themselves up by their jockstraps, or would they find their testicles squeezed even further?

CHAPTER 2

Ally, the Ultimate Warrior

IN TERMS OF GRANDEUR AND excess, the pre-season trial at Pittodrie – first team versus reserves – was a sepia-tinged event and therefore quite unable to compete with anything as colourful as the Lord Mayor’s Show. But, if it scarcely stirred the senses, it occasionally delivered a sound bite as to the team’s possible progression or, for that matter, regression. The 1960-61 event, however, simply scattered any negative preconceptions to the four winds. Charlie Cooke, a month or so short of his 18th birthday, delivered a calling card that was embossed in gold. Not only did he steal the show on ‘stage’, but he also bloody well produced and directed the production. These days, television pundits talk endlessly about the No. 10 slot. It’s become the precious position, as if it never existed previously. Well, here, before our very eyes in the year of 1960, the definitive No. 10 was unveiled. Charlie had it all and then some more besides. His looks were such he might have pursued his luck in Hollywood, but the gifts didn’t end there: he had wondrous ball control, a vast range of passing options, and a plethora of dribbling skills that made the mouth water and beg for more.

The unlucky soul in immediate receipt of this tour de force was Ian Burns. Now Burns, a part-timer and a committed and aggressive replacement for Jackie Allister, had a career in insurance, but no short-term policy could equip him for what was on offer that evening. Exertion often encouraged Burns’ face to assume a reddish hue. By the end of these proceedings, his face replicated the colour of an Aberdeen pillar box. He had tried to deny Charlie Cooke space; he would have had more chance subduing an affray in Craiginches. The crowd, for their part, wanted to know the identity of this magnificent specimen who betrayed not even a semblance of first-night nerves. Not quite believing their luck, they wondered why he had arrived at a club that, at the time, was virtually auditioning for an appointment in the breakers’ yard. The story should have been, like Cooke, complex. Instead, it was simple and over, indeed, before an eye blinked. Bobby Calder, the extraordinary little man who scouted so many stars for Aberdeen, had worked the oracle again: ‘Just think Aberdeen, Charlie. Don’t let it leave your mind. You’ll love it there – and be in the first team in no time at all.’ In effect, by convincing this adopted Greenockian (Charlie was born in St Monans, Fife) to ignore overtures from nearly every club in the land and travel north from Renfrew Juniors, he had completed his life’s work. As far as we Dons fans were concerned, we had found a legitimate hero and also confirmation of our wildest dreams. A few thousand of us went home that night drooling over an envisaged golden future.

Today, over half a century later, I still wonder what in damnation went wrong, because it did go wrong. But, there were mitigating circumstances in that Charlie was a law unto himself and, on occasion, was living life to its limits. Long-serving full back Jim Whyte recalls the inconsistency in his make-up. ‘Some days, he’d go out for a couple of laps to warm up; he’d be away like the clappers, a full lap in front of everybody. The next time, he’d be a lap behind. So one day he was busting a gut, the next he couldn’t be bothered.’ It was the same in competitive games; brilliance one day, average or worse the next. Could it have been that the rather irregular lifestyle was responsible?

But, rather than focusing on what would be a rather unfortunate ending, for the club if not the player, let us first examine the credentials of the other man who was responsible for the signing of Cooke. If sporting history had a face, it would most likely frown on Tommy Pearson. Although he’d enjoyed a charmed existence as a footballer with Newcastle United and latterly Aberdeen, the charm forfeited its sheen after six years as manager of the Dons. Those years mirrored life living on a switchback: it was Cooke-esque: exhilarating at times, tortuous at others. The training, let’s say, was scarcely exemplary. Whyte illustrates a typical Friday session. ‘You didn’t need to get stripped. You’d just take off your jacket, roll up your trousers and put your spikes on. Then it was a couple of shuffles down the grandstand side and that was it. Honestly, that was training under Pearson. Some of the players stripped, some didn’t, Jimmy Hogg, for instance, used to roll up his trousers, saying, “F*** this…”’

Nevertheless, there was a side to Pearson that was comfortably distanced from incompetence. Some of today’s managers are apprehensive of youth. It would appear we have one at Aberdeen at the moment. Pearson, though, had undeniable bravery and a sense of adventure: he may have been a managerial tenderfoot, but he pledged to give the young ones their chance and, by God, he did just that. In doing so, he signed two of the most influential players who would ever wear the red jerseys. Cooke, in spite of his foibles, was one. Alistair Stewart Shewan, who joined in 1959, was the other. I shall come back to him in a moment.

First, I am anxious to talk to Cooke, who now runs a coaching school in Cincinatti. I believe I first met him in Valencia back in 1975 when Scotland were trying to qualify for the European Championships, and I was attempting to hold on to my job with the Scottish Sun. Neither Scotland nor I succeeded. I cannot remember the exact exchange between us because I was comprehensively pixilated when I fell upon a reception for the international team. But I fear time and strong drink had removed the gloss from my adolescent hero worship and perhaps I was not as respectful as I should have been. Hoping to atone, all these years later, I send an email to the soccer school’s Ohio headquarters and their response is delivered in the time it takes to trim an eyebrow. They promise to send the missive on. There is no reply. Cooke, I can only assume, doesn’t appreciate my anxiety. Perhaps he remembers Valencia. I don’t. What I do recall is sleeping in the wrong room and keeping an SFA selector out of his bed – a story delineated in full in an e-book of mine, Fingerprints of a Football Rascal. There again, considering the wild stories that pursued Cooke in his four years at Aberdeen, maybe he cares not to remember that segment of his past. The story, I’m confident, will manage without him.