6,71 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Mercier Press

- Kategorie: Ratgeber

- Sprache: Englisch

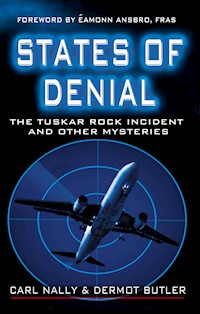

Unidentified Aerial Phenomena, which fly in the face of the laws of physics, intrude upon all aspects of aviation around the globe. These conundrums seem like tangible proof that the universe is a much stranger place than humanity, with its 'consensus reality', is willing to accept. Among the cases discussed by the authors, one particular event was instrumental in directing their research into aerial phenomena: the mysterious demise of an Aer Lingus airliner close to Tuskar Rock. This case suggested to them that paranormal events were at work in the fatal incident. Other cases explored indicate that the unexplained is more prevalent than anyone has dared to imagine. From bizarre time and spatial displacements, to unknown aerial craft firing beams and interfering with nuclear missiles, this book's contents will ensure that no one will ever look at the sky in quite the same way again.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

MERCIER PRESS

3B Oak House, Bessboro Rd

Blackrock, Cork, Ireland.

www.mercierpress.ie

http://twitter.com/IrishPublisher

http://www.facebook.com/mercier.press

© Miriam Hamilton, 2012

ISBN: 978 1 85635 935 1

Epub ISBN: 978 1 78117 043 4

Mobi ISBN: 978 1 78117 044 1

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

This book is dedicated to Colin, who has supported and encouraged me throughout all we have been through; to David, Paul and Samuel, my adorable boys; and of course to Caroline, my beautiful and brave daughter.

1. THE GOOD NEWS

There is definitely a sixth sense in women. It is not really a feeling; it’s even more innate than that. It is a gut instinct that tells you to do a pregnancy test now, right away. I got that sense on a rainy, depressing Monday in January 2008 as I left school at lunchtime to get a coffee and a break from the back-to-school chaos that accompanies a new term. No matter how long they have been in schools, most teachers of teenagers would agree that on the first day back after holidays they feel a hint of trepidation, which they overcome by marching into the first class of the day and getting on with the drama of their teaching life. The morning had gone okay for me, except for the niggling feeling that I had to get to a pharmacy to do a pregnancy test. It was ridiculous, really; my husband Colin and I had decided quite quickly over Christmas that we would love to have one more baby and, since I had just turned thirty-seven, it seemed unlikely that we would be lucky enough not to have to wait at least a few months. As I walked towards the shops, I found myself wondering whether there was any point in wasting money on a test, as my period was not due for a few days. But I knew myself well enough to realise this attempt at being rational was futile; I walked on into the pharmacy, led firmly by my gut, and promptly bought a pregnancy test.

I then went to a small café and ordered a coffee, finding myself asking for a decaf to be healthy (just in case), and went off to the ladies to do the test. Back at my table, I sipped at my coffee for the few minutes the test would take, and then, as covertly as was possible in a full café, sneaked a glance at the result. For a few seconds I had the sinking feeling I’ve always had when a pregnancy test has been negative – the pink line I was looking for in the test’s second viewing window didn’t appear. With a pregnancy test, however, it seems impossible to take just one look at the result and put it away. I found myself examining it more carefully, turning and twisting the testing stick around in the light, almost wishing for the line – which would indicate a positive test – to appear. Then I thought I saw something, as the light caught the testing stick from one angle in particular. I raced outside to check more carefully. Sure enough, the faintest line imaginable was visible in the second window. I could not believe it and stood for a moment in total surprise. An excited smile began to spread across my face as I thought, ‘Welcome, baby number four.’ Little did I know at that moment that this little baby was going to turn our lives upside down.

***

Colin and I had started our family in 2000 with the birth of our son David. This first pregnancy introduced me to the wonderful world of internal examinations, being dry shaved in the nether regions by a complete stranger, and the joys of the pre-op enema. David was delivered by elective Caesarean section a week early, as he was in a breech position – intending to be born feet first instead of head first. Everyone advised me that it would be best if I chose to be awake for the delivery. My advisers were mostly male doctors, anaesthetists and women who had no children or who had experienced only natural deliveries. Even my own husband insisted it would feel more like a real birth experience if I was awake. That I agreed to this reveals, I suppose, my clearly significant levels of ‘baby brain’ – a temporary period of naivety some pregnant women experience, which included, in my case, unerring trust in the instincts of everyone but myself.

Yes, I had a real – and memorable – birth experience all right, but a terrifying one. I had experienced nothing quite like that long-awaited delivery day: willingly walking into an operating theatre, with all manner of glistening silver instruments on view, and propping myself up on a narrow table to have a spinal block inserted into my back before I willingly lay down, wide awake, while I was cut open and had my baby hauled out. I’m sorry: I cannot romanticise the experience in any way, because for me it was horrifying.

It was not that there was any sensation of pain, but the manoeuvring to get the baby out was certainly uncomfortable and frightening, and I had read far too many books, so I was completely tuned in to every step. Throughout the whole operation – from realising for the first time, as they put the blue screen right up in front of my face to block the view, that I have claustrophobia issues, to hearing the sounds of the suctioning and knowing that they were removing the amniotic fluid around the baby – I shook with fear. The staff were brilliant, especially the anaesthetist, who tried to keep me calm. But I told myself that if I had another child I would love to give birth naturally, despite the pain, and that if I ever had to have a Caesarean section again I would insist on being under a general anaesthetic, sound asleep.

David was handed to me to breastfeed, but by this time I was so heavily sedated I could barely keep my eyes open to see him, let alone feed him. He was very handsome, however, like his dad, and I did bond with him soon afterwards, once the drugs and adrenaline coursing through my veins had dissipated. He was a healthy 7 lb 5 oz (3.32 kg), delivered at thirty-nine weeks on 31 October. He is our little warlock, with his Hallowe’en birthday.

Our second son, Paul, arrived in 2002, just nineteen months after David, and, as planned, I insisted on a natural delivery. I did have to push this slightly (pardon the pun) at the hospital, as there were worries that I had a slightly increased risk of uterine rupture, having previously had a Caesarean birth. I had done lots of research on vaginal birth after Caesarean and found that the risks were marginal, as long as the delivery was monitored carefully throughout. Having signed all the forms indicating I was aware of the risks, I prepared myself for my first vaginal delivery. I had an internal examination (often simply called ‘an internal’) on the day Paul was due, and was informed that my cervix was already two centimetres dilated – my cervix was beginning to open and labour was impending. I was pleased with this news as the long pregnancy was coming to an end and I was looking forward to my baby’s arrival. I went home with the advice that it would only be a matter of days before labour would begin.

That evening I experienced a bit of bloody mucus, commonly called a ‘show’, but this was to be expected after the internal, so I went to bed unconcerned at ten o’clock, with a Harry Potter book. Colin had already been demoted to the spare room, as I was by now extremely large and needed the whole bed in which to manoeuvre and spread out comfortably at night. At about eleven o’clock I heard a popping sound. My first thought was that Colin was having a bottle of champagne on his own (an early celebration of the birth of our baby) without me, in the spare room. Then it dawned on me that we had no champagne in the house – we rarely do – and, besides, Colin was snoring audibly next door. My second thought was that I was having a terrible accident, as I felt warm liquid flowing down below. My third was the realisation that my waters must have broken: I had no control of the liquid, which by now was soaking the bed. I jumped up, as athletically as I could at forty weeks’ gestation, and grabbed the sleeping bag I had luckily put on the bed earlier that evening. I then hobbled, with the bag gathering fluid at a fast rate and getting heavier with every step, out to the hall to try to wake Colin. He wouldn’t wake. Reluctant to wake David, who was obliviously sleeping further down the hall, I had to squeeze very inelegantly through the bedroom door and give Colin a kick. After a few minutes he was up and we were on our way to the hospital.

I felt every bump on the journey, as by now I was experiencing light pains and the baby’s head was banging down on my cervix without the fluid to cushion it. We got to the hospital at midnight, and I was advised to get into my bed and sleep. I was far too excited for that. I walked up and down the aisle of the ward to get things going. This proved to be quite entertaining, as there were other women who had also clearly read the pregnancy books about the powers of gravity and movement in progressing labour, doing the same thing. We would exchange apprehensive but knowing glances as we silently passed each other on the corridor, lean against the wall when the contraction hit, and then shuffle along again. I remember wondering whether there might be a need for a ‘Hospital Ward Walking Policy’ if pregnancies continued rising in number as they had in recent years – a sort of rules-of-the-road-type thing: ‘Women must give way to other women coming out of the ward, or overtake on the right, never inside, to allow for a contracting woman who is hogging the hard shoulder.’ Within about six hours I had dilated to a significant enough degree to be shipped to the labour ward for some pain relief.

Going through the labour ward to get to my delivery room was like being in the scene in the film The Silence of the Lambs in which Clarice Starling passes along the cells on death row and the awful noises and sounds frighten her. It was noisy, and for the first time I heard the primal screams of women nearing the end of their labours and pushing their babies out. The midwife saw my face and advised me to try not to take any notice of the screaming, saying, ‘Everyone deals with the pain differently.’

We passed room after room on the way to the delivery bay where I would spend the coming hours. The staff there gave me the gas and air – sometimes referred to as laughing gas – commonly used as mild pain relief during labour. The gas and air was great fun for a while, until it – or the pain of the contractions, I am not sure which – made me feel really sick. By eight o’clock I was insisting I needed an epidural (spinal block) because I didn’t think I could cope with much more. I think I expected labour pains to be like a dull ache, as I had heard so many times that they were like period pains but a lot worse. For me they started out like that, but soon I was surprised by their sharpness: they felt like the combination of a bad ache with the pain of a sharp knife cutting right down onto my cervix. I remember thinking that the gallstone pain I had had a few years earlier was the only pain even vaguely resembling this. Yet this pain felt productive: I could feel it pushing my cervix painfully apart and therefore I could rationalise it to some degree. I remembered reading all the books that warned mothers not to panic as the pain intensified. Yet that was exactly what I did. Negative feelings that I couldn’t possibly live through this began infiltrating my thoughts. I desperately awaited an epidural.

By ten o’clock the next morning, the anaesthetist had administered the epidural, and I felt great. Initially it left me with only slight tightening as I contracted, but no pain. I was so relaxed I could flick through a magazine and chat, because the contractions were no worse than the practice Braxton Hicks contractions – mild, usually painless, contractions or tightening of the uterus, which occur in many women near the end of a pregnancy – I had already experienced. I was really happy and looking forward to a pain-free end to the birth.

A few hours into the epidural, however, I began to feel pains that worsened steadily. I mentioned them to the midwives, who checked my back and realised that in turning over during labour I must have detached the tube inserted there to administer the epidural drugs. It would be a few hours before the anaesthetist – occupied by an emergency Caesarean section in an operating theatre – could replace it. All hell broke loose for me then, in terms of pain. I went from the blissful situation of virtually no pain into the transition phase of labour – the final phase of dilation up to ten centimetres, prior to pushing the baby out. This is the toughest and most difficult stage for many women as the contractions are at their strongest and most frequent. It is the peak of the first stage of labour and transitions the mother into the next stage, when the baby is born. This was excruciating. I panicked even more than I had earlier. I was crying and fussing – not doing very well at all. I remember feeling as though my back would break. No amount of rubbing or moving around did any good. I remembered seeing the videos of women who moved around right through their labour, and I marvelled at how anyone had the strength to stand up, literally, to pain like that which I was experiencing.

By one o’clock the anaesthetist was free to attend to me, topping up the epidural as I began the pushing phase of labour – during which the pregnant woman puts her chin on her chest and pushes down into her bottom, as if passing a stool. This pushes the baby through the cervix with each contraction and into the birth canal, until eventually the baby emerges from the vagina after many long pushes. Before long Paul was crowning – beginning to emerge from the vagina with each push, but going back in between pushes. Because he was being monitored continually due to the risk of uterine rupture, the midwives discovered he was getting tired. I overheard them mentioning that they would have to intervene. I mistakenly jumped to the unwelcome conclusion they were talking about a Caesarean section, but they quickly clarified it was far too late for that. I realised they were talking about an episiotomy – a cut into the vagina to help release the baby. I begged for a few more minutes to push, arguing that an episiotomy was not part of my birth plan, in an attempt to put them off the idea. Paul was a big baby, however; Colin ventured a look down below and suggested that I might as well have the cut as I was tearing myself anyway. It wasn’t the most helpful comment I have ever received in labour, but I conceded defeat. The last thing I remember seeing after the stirrups were wheeled in, and my feet were secured in them, was a doctor approaching me with a pair of scissors in one hand and a large set of silver forceps in the other. I looked away as I gave a final push and, with assistance, Paul was born. The hospital staff stitched me up while I fed my new 9-lb (4.08-kg) baby. Although vaginal childbirth had been a scary experience, I felt that through it I had completed one of the female rites of passage. I was very sore, but I was elated that Paul, my second beautiful son, had arrived.

In 2006 our third son, Samuel, was born. This time my pregnancy continued beyond the due date, so I was admitted to hospital for ARM (artificial rupture of the membranes), during which a crochet hook-like instrument is inserted into the vagina and up through the cervix to nick the amniotic membrane and release the waters so that labour can proceed. Two things made me suitable for this procedure: my cervix was again two centimetres dilated – which allowed the instrument into the vagina to nick the membrane – and I had laboured well after my waters had broken in my previous pregnancy. At three o’clock in the afternoon my waters broke, and by a quarter past seven that evening Samuel had been born. His birth was quick, intense and a very positive experience, because I harboured none of the fear or panic I had previously experienced about how bad the pain would get. This time I knew what would happen and I was prepared: I was adamant that I did not want an epidural, because I wanted to have full sensation for the pushing stage and I wanted to be back on my feet after the birth. I managed on gas and air and with the use of a TENS machine, which works on the principle of suppressing pain signals to the brain and encouraging the release of endorphins, with the effect that the sensation of the pain is diluted to some degree. I have no idea if the machine had any effect, as the labour was tough, but I was calm and went into a kind of meditative state: every time I had a contraction, I focused on a clock’s small hand ticking round and just breathed slowly and deeply. I felt well in control right to the last push, when Samuel was born.

He climbed up to my breast to feed himself, which was amazing to see, and was an easy-going, relaxed baby from day one. Perhaps a calm, uneventful arrival suited him – who knows? He was fair and placid, and a happy, handsome third son. I was proud of how I had managed through his birth and thrilled with my complete family (Colin and I had decided three would be more than enough children for us to bring up). I think that is partly why I was particularly excited about my fourth pregnancy, as it was quite a spontaneous decision that was realised very quickly, which made it seem as though it was meant to be and was part of our family’s fate. Of course, I had no idea of what we were to face as a family in the months that followed.

***

Once I had absorbed the positive result of the pregnancy test, I phoned Colin to tell him the news, which surprised him as much as it had me. We settled into a period of lovely evenings during which, once the children were in bed, we chatted about what life would be like having four young children. We debated whether we would have a boy or girl. Both of us felt the baby would probably be another boy, since we had had three already, and that was great. We genuinely did not mind either way, as long as the baby was healthy. We knew we would have to change our car to a seven-seater to fit in four children with their safety seats. I spent time discussing when I should take maternity leave and relished the prospect of a considerable spell of time at home with the whole family.

I had met Colin when I was studying in London and had remained there working as a teacher after qualification. When we married we decided to move to Ireland to raise a family. However, after we moved back Colin found that his career never really took off. Outside Dublin there were few opportunities for the museum and exhibition-design jobs or model-making that Colin had enjoyed for many years during a successful career in Britain. Owing to the security of my job, we were not overly concerned when work prospects were poor in Colin’s area of expertise. We had always felt strongly that one of us should be a full-time carer for our children; it naturally evolved that Colin looked after the children, with a view to returning to work if an opportunity arose in our location. We had a good quality of life, as I had ample holidays to spend with the family at home and felt that work did not interfere hugely with my home life.

Before long our discussions began to focus on my age: I was thirty-seven. Colin was forty-seven, so neither of us were at an optimum age for reproduction. I was very much aware that most mothers-to-be in the over-thirty-five bracket get on well, with no problems. But I had read the literature, and all the books had a section on older mothers and how being older posed risks for both mother and baby, but particularly raised the baby’s risk of problems. I was therefore also aware that I was at higher risk of conceiving a baby with an abnormality than younger women were. I had no worries around my own health, as I was fit and had been training hard as an athlete up until the time I had conceived Caroline. I was carrying no excess weight, had normal blood pressure and experienced no medical issues. I did worry, however, about the risk of my eggs’ DNA being older, and therefore possibly less healthy, than that of younger women. It is easy to play down the risks of an older mother when most have no issues, but often we do not hear of the more negative stories and I was concerned. I felt lucky to have had three very healthy boys; a little bit of me felt I was tempting fate by having a fourth at this age. I decided I would discuss the issue at the hospital when I got my appointment and take it from there.

2. ANTENATAL CARE AND THE FIRST SPECIAL SCAN

My antenatal care, as is the norm, began with a visit to the family’s general medical practitioner, who did the initial checks, such as weight and blood pressure, and noted dates. A letter from the maternity hospital followed, giving a date for my first scan, due when I had progressed to fourteen weeks’ gestation. I was aware that the issue of miscarriage was significant up until that date. I hoped I would be all right and that the pregnancy would progress. Having had no bleeding in my previous pregnancies, I felt confident that all would be well in this area. As had been the case with the boys, I was able to enjoy the knowledge of the new pregnancy for only about two weeks until the familiar sensation of morning sickness appeared, when I was around eight weeks pregnant. This was for me the very worst symptom of the whole of pregnancy; I would wake in the morning and only five seconds would pass before the horrendous feeling of nausea would travel through my system. I would feel shaky, weak, tired and sick. The feeling would subside temporarily if I ate something there and then, but would soon be back, sometimes within half an hour. My sickness would last on and off all day. I remember having to leave the classroom where I was teaching to run to the toilets to throw up. I would return shakily to continue the lessons as if nothing had happened. I looked green for the first three months; people who knew me could tell I was pregnant.

When I got home from work I would get into pyjamas, flop on the couch and move only to go to the toilet. I had no interest in anything but passing the time until I felt well again, which I knew would take many weeks. I rarely managed to stay up past the nine o’clock evening news and, despite often having twelve hours’ sleep, I would awaken exhausted. It always amazes me how babies manage to develop properly when mothers are so sick in pregnancy. It seems an evolutionary blip that a mother is not able to eat well in the crucial first trimester of her baby’s development. At the same time, the nausea does force expectant mothers to take it easy, which perhaps balances things out. So, the first trimester of my fourth pregnancy, as had been the case with my earlier pregnancies, passed in a haze of nausea, exhaustion, work and sleep. My thoughts focused solely on my first scan, which would not only give me a glimpse of my baby but also herald the end of the dreaded sickness and the beginning of the enjoyable second trimester, during which things would get much better – or so I expected.

I awoke to bright sunshine on the day of my scan, still feeling wobbly but not as bad as I had been. The name of the consultant assigned to me for my pregnancy appeared on the hospital letter. I took little notice of who it was, as I had chosen, as was the case with all my pregnancies, to use public rather than private medical services. It never really entered my head to do otherwise. Going private would have meant I saw the same consultant for all my antenatal appointments in his or her private rooms, rather than at the hospital. It may have meant that the consultant would deliver me, if he or she were available, and it may have meant a private room for me. I am not a great fan of the public–private divide in our health system and believe patients should be seen according to their health needs and nothing else. Choice is fine if you have one. Private rooms should be for the sickest patients to rest in, and not for those who can buy them even if their procedure is routine. I had no problem with being in a ward with other women; in fact I believed I would enjoy chatting to them and giving and getting advice on motherhood and breastfeeding. After all, it would only be for a few days if all went well. For the previous three pregnancies I had briefly met the consultants: once or twice with David to discuss the breech-birth scenario and the need for a Caesarean section, once with Paul to sign the forms and discuss the vaginal birth after the section, and not at all with Samuel. The midwives and doctors had looked after us well and I did not expect to meet the consultant this time either.

The first hospital appointment in a pregnancy is always long, and this one was no different. I went in to speak to a midwife, who discussed my medical history, including all three previous pregnancies, in detail. Colin and I mentioned family members on both sides and any health issues of which we were aware. I have always enjoyed this bit of the appointment, as it is a bit like an informal, relaxed chat and an acknowledgement before the scan happens that I am really going to have a baby. The midwife asked me to consent to an HIV test to check for potential AIDS, and this brought home to me that I was solely responsible for maintaining a healthy lifestyle so that my baby had the best chance of a great start in life. I was soon to realise that, despite a mother’s best efforts, things can go wrong.