12,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Northway Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

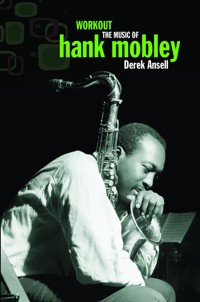

John Lenwood McLean – sugar free saxophonist from Sugar Hill, Harlem – is widely known as one of the finest, most consistent soloists in jazz history. From early in his career Jackie's powerful, unsentimental, sometimes astringent sound and inventive style made audiences and critics sit up and listen. Steeped in – but eventually moving well beyond – the influence of his mentor and friend Charlie Parker, he built an attractive, instantly recognisable musical personality. As author Derek Ansell says, his career trajectory is far from the typical jazz story of the tragic artist in which early brilliance leads to later decline. McLean's story is one of glorious triumph over the drug addiction that affected so many of his friends and might have destroyed him. Able to produce uniformly fine recordings through the darkest periods of his personal life, he saw his reputation as a musician steadily grow and became not only a living legend as an improviser but a much respected educator whose students carry on his legacy. Fortunately, McLean's discography is large and Derek Ansell is a surefooted guide through the recordings, presenting them in the context in which they were made and indicating the special gems among a vast body of recorded work that is one of jazz's greatest treasures. "Derek Ansell's exuberant new biography... And a powerful read it is too." Morning Star "Ansell is an expert on post-bop American jazz, having already produced a book on Hank Mobley for Northway... and this study of McLean is – like Workout, the Mobley book – packed with a keen and enthusiastic listener's insights into the recorded work; unlike the Mobley book, however (which, as its subtitle 'The music of Hank Mobley' implied, focused chiefly on the tenor player's recordings), it also provides a wealth of detail on McLean's life and beliefs.... McLean never completed his autobiography, but this respectful, perceptive study goes some way towards compensating his many admirers for this loss." London Jazz "A must-read for jazz fans... Ansell's... encyclopaedic knowledge of the world of jazz helps add luscious colour and exhaustive context to an already remarkable tale." Newbury Weekly News Derek Ansell writes regular reviews of live jazz and classical music for magazines and newspapers and has contributed more than two hundred articles and numerous interviews, record and book reviews to Jazz Journal International. He is the author of Workout: The Music of Hank Mobley (Northway Publications) and a book about the music of John Coltrane (forthcoming). He has also written three novels (two published and one forthcoming).

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 324

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Ähnliche

SUGAR FREE SAXOPHONE

Published by Northway Publications

39 Tytherton Road, London N19 4PZ, UK.

www.northwaybooks.com

Copyright © 2013, Derek Ansell

The right of Derek Ansell to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Cover design by Adam Yeldham, Raven Design

Cover photo by Francis Wolff © Mosaic Images LLC

1. Time Warp: One: Sitting in for the Bird

The young man coming out of the Subway at Houston Street in New York City, looking very smart in a blue suit with a white shirt and a tie, is a young musician named Jackie McLean. It is 1949, a few years after the end of World War Two, and bebop, as it is commonly known, is the new jazz sensation, the modern sound of jazz that most youngsters are listening to, and a few, like young McLean, have been learning to play. He is eighteen years old and a particularly good player on the instrument for one so young. So good, in fact, that he was heard playing in a band a short time ago by alto saxophonist Charlie Parker, known as ‘Bird’, the main soloist and principal innovative force in the new modern jazz. That is why he is emerging from the subway now, en route to Chateau Gardens where drummer Art Blakey and a combo of modern jazz musicians will be arriving shortly to begin their first set.

Earlier that day young Jackie had arrived home to find his mother in a state of excitement, telling him that although she didn’t think he was going to believe it, Charlie Parker had been on the phone. The young man had eagerly demanded to know what the message from Bird was. Parker had asked that Jackie should wear a blue suit, go down to Chateau Gardens and play for him until he arrived, later in the evening.

After the initial shock, the excitement and then the first flush of pleasure had subsided a little, Jackie had spent the rest of the afternoon practising on his alto sax and then, dressing slowly and meticulously, had taken the subway to Houston Street for Chateau Gardens, a place where they played jazz and dances in downtown Manhattan.

Now, once inside the Gardens he approaches the bandstand eagerly, if nervously, and waits for Art Blakey, who knows him, to arrive... He is, in his eagerness and excitement, the first to get there. This is a big day indeed for the young saxophonist. Parker does not easily, or indeed usually, send in subs to play for him until he arrives; more often than not he just gets there late or when he is ready or forgets the gig altogether but, when he does put a sub in, it is always an experienced, older player who has played around the scene for years and years. Parker must have a high regard for this youngster.

When Blakey and the other musicians arrive, Jackie gives the drummer Parker’s message and Art says ‘OK.’ He knows Parker well and he’s seen and heard young Jackie McLean playing in bars around town and knows that this is what Bird wants. He announces to the audience that Parker has been delayed but he will be there later to play – and meantime, this young musician named Jackie McLean is going to play. Many years later, McLean confided to historian Ken Burns that he could feel the disappointment rippling through the audience as Art made his announcement, but it could not put the young man off; this was his big opportunity and he was going to take full advantage of it. With the master’s blessing.

He begins to play with the band, calling the tunes in Parker’s absence but with Blakey’s approval. He plays ‘Confirmation’, ‘A Night in Tunisia’ and then ‘Now’s the Time’ and the ballad ‘Don’t Blame Me’. These are all compositions very familiar to Charlie Parker, items that he plays regularly and selections that Jackie has played over and over again, trying to get that elusive, cutting Parker sound, that hip bebop phrasing that all the young alto players are attempting to emulate. Maybe, even as early as this, there is the hint, just a hint of a personal sound beginning to filter through, a sound tinged with the blues, perhaps a shade sharp, something that will become a personal attribute in his later playing but not yet audible to the average jazz fan in the 1940s.

Jackie McLean was always a forceful, assertive young musician, even in his earliest days but at this time, with the all-pervasive influence of Parker on every modern jazz musician, it is that sound that predominates, in his phrasing, in his main attack, in his rhythmic approach. In any case, he is anxious to play Parker tunes that the audience will be familiar with and enjoy hearing. The bebop anthems are familiar to the audience to the extent that they often hum the opening melodies at the start of each selection. Jackie is playing wild bop, tearing it up, fashioning new phrases, swinging, and riding exhilaratingly on top of Blakey’s cymbal beat.

He is enjoying himself immensely, running through the chord changes, hearing the surging lift that a rhythm section with Art Blakey in it gives to every soloist. Then there is a sudden surge of people at the back of the stage and, as Jackie looks up and notes the dense mass of the crowds, he sees a saxophone case being raised up high and another surge of people. They follow the newly arrived Charlie Parker all the way down to the bandstand and stand there jostling eagerly, waiting for him to get up there and start playing. But Parker, taking his time in leisurely fashion, signals up to young Jackie to keep playing, which he does. Bird gets himself on the stage, takes out his horn, adjusts it, fixes his reed, as Jackie prepares to pack up his instrument and depart. Parker smiles at his protégé and says ‘Play one with me,’ so the two saxophonists join forces as Blakey begins to stoke up fires in the rhythm section and drive the two soloists forward. Parker is a hero in the community at that time and everything he plays is listened to in awed silence by the audience. The sheer excitement of being on the same stage, in the same band as Parker is almost overwhelming for Jackie McLean. But he’s enjoying every minute of it.

Finally, it is time for Parker to take full control and command of his combo and get down to the serious business of playing bebop, getting some modern jazz cooking in earnest. He smiles at Jackie and tells him to go and sit out front and he will see him later. Jackie is soon so immersed in the music of Parker and the band that he almost, but not quite, forgets why he is there. Parker plays brilliantly, far into the night and, at the end, he seeks out Jackie, who is still there in the audience, tapping his toes and nodding his head, and gives him $15, a lot of money for a gig at that time. It is a great night and a defining moment for Jackie McLean of Sugar Hill, Harlem. It is possibly the first indication that he will have a long and distinguished career in jazz, in music of quality, and something that he will remember and recount many long years after the event.[1]

2. Sugar Hill, Harlem

The Sugar Hill district of Harlem in New York City is bounded by 155th Street in the north and 145th Street in the south. The area looks out over Manhattan from high up, giving views of the Harlem River. Jackie McLean lived in this district from the age of twelve, surrounded by young people who would also become jazz soloists. An early neighbourhood band featured him with two saxophonists, Sonny Rollins and Andy Kirk Jr., and the pianist Kenny Drew. Another local was drummer Art Taylor. He became friendly with Rollins early on, as did Richie Powell and later his brother Bud. The area had always been a haven for artists and jazz musicians and it was here that Billie Holiday often appeared, along with Duke Ellington, Arnett Cobb, Don Redman, Nat King Cole and many others.

Many years later, Jackie would refer to himself as a ‘sugar free saxophonist’ and commentators were never quite sure whether he was referring to his direct, hard sound on the saxophone or his home area. He often referred to himself as being lucky to grow up with all those great musicians on his doorstep, sometimes quite literally, and especially with pianist Bud Powell. Powell had been the major soloist in the bop revolution in the early 1940s and an important innovative force on his instrument, along with Parker on alto sax and trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie. Powell obviously heard something in the young McLean’s playing and helped him by showing him different chords and giving him instruction. Jackie was only fifteen when he began meeting up with Powell and had been playing alto sax just for a year or two. This would have been in 1946 and it was shortly afterwards that young McLean started playing truant from school, putting his school books in a subway lock-up and heading down to the Apollo theatre to hear Parker play.

John Lenwood (Jackie) McLean was born in NYC on May 17th 1931 and, although some sources claim his birth date to be 1932, his widow, Dollie McLean, confirmed the 1931 date. He grew up listening to people like Coleman Hawkins, Count Basie and, through Basie’s orchestra, the early solos of Lester Young. Young seems to have been an early and very important influence, a man who, Jackie felt, was the one who really started bebop, or modern jazz. As he put it in his interview with Ken Burns, talking about Billie Holiday’s recordings that feature Lester Young solos, ‘You’ll hear, back as early as 1937, ’38, ’39, his style was already developing beyond what the music sounded like before that. There were a lot of eighth notes... and the two feel was beginning to disappear, and a lot of triplets and grace notes.’ Jackie went on to point out that Lester’s sound was much lighter than that of Coleman Hawkins who had a ‘deep, velvety vibrato’.[1] Young had a lot less vibrato and this, in turn, influenced Charlie Parker who took it much further and then, when he met up with Dizzy Gillespie and Thelonious Monk, helped to develop this wonderful music.

Jackie claimed Parker, Lester Young, Dexter Gordon, and Sonny Rollins as his favourite saxophonists in the early years but it was Bud Powell that he claimed as his main influence. It was to Powell’s house that he would head after school to study, to learn and to jam. It was at some point later that Young became a major influence, almost as strong as Parker. Jackie talked about bebop and what the word meant to him on several occasions, and was convinced that Young was the originator. Evolving out of his concept and his solos, Jackie felt that the way Lester played, from when he was with Count Basie in the 1930s, was the beginning of bop soloing and he often quoted a phrase Young played on ‘I Never Knew’, a phrase that came before the melody.

So young McLean listened to jazz at home in Harlem. He had little recollection of his father John McLean Sr. who died when he was just seven years old. John Sr. had been a jazz guitarist of some stature having played with swing musicians like Tiny Bradshaw and saxophonist Teddy Hill. He is reported to have locked himself and his son in a room, sat him up on a dresser and played the guitar to him. Jackie’s mother, Alpha Omega McLean, had little time for musicians and Jackie could only remember seeing his father three times. Then, one day in midwinter, John Sr. slipped on ice in the street, hit his head on a curbstone and died in hospital two days later. After that Alpha worked hard as a domestic, bringing her son up on her own, and studying until she qualified as a laboratory technician, although much later she became a schoolteacher.[2]

When Jackie was twelve years old his mother remarried and his new stepfather, Jimmy Briggs, became much more influential and helpful to him than his own father had ever been. Jackie and his mother moved from their home in Washington Heights to live with Briggs at 185th Street and Nicholas Avenue in the Sugar Hill district. Briggs owned a record shop at 141st Street and Eighth Avenue which specialised in jazz, and young Jackie would soon start to work there, selling albums by day and in the evening shutting up shop and retiring to a back room to study and listen to the latest jazz releases. Jackie’s mother had referred to his father as ‘a no good musician’ and at first opposed his interest in learning to play an instrument but he must have talked her round at some point and she capitulated. He also worked on his godfather, Norman Cobbs, who played saxophone in the band at the Abyssinian Baptist Church which the family attended. Cobbs gave him his first instrument, a soprano saxophone, but Jackie was reported to have been disappointed with the soprano and really wanted an alto.

His first alto saxophone, bought for him by his mother, arrived when he was thirteen years old. He linked up to talk, hang out and practise with Rollins, Drew and Taylor and received crucial, priceless help, encouragement and instruction from Bud Powell. By this time he had also started to listen to records by Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster and Lester Young, brought home for him by Jimmy Briggs.

In the liner notes to his Prestige record Makin’ the Changes, Jackie tells Nat Hentoff: ‘Bud made me play by ear, and taught me a lot about chords. Sometimes I’d come by his house on a Friday afternoon and we’d play, off and on, until Sunday.’ McLean admitted that he did not understand or take in everything Powell told him; he was only about sixteen or seventeen at the time. But he is credited with getting young Richie Powell playing the piano, saying angrily to him: ‘You’re Bud Powell’s brother, how can you not play?’ Richie had been responsible for introducing Jackie to his brother after the youngster went into Briggs’ record shop and told McLean who he was.

Many reports claim that McLean did not learn harmony or theory directly from Powell but that the pianist worked on the young man’s ear. Powell would play something on the piano and get Jackie to play the chord changes behind him until he learned to improvise freely around them. After some time and a lot of practice, Powell took Jackie to Birdland with him and during the evening called him up on the bandstand to play. That was an honour for Jackie and he never forgot it. Priceless help, then, from a master although, looking ahead to Jackie’s early experience playing and recording with Miles Davis in 1951 to 1956, teaching him to play by ear may have held him back as, according to Davis, the young McLean was lazy and would mostly play by ear. He was reluctant to take the time and trouble to learn popular standard tunes which were, then as now, the backbone of many a modern jazz musician’s repertoire.

The neighbourhood friends and acquaintances in the area where he lived must have been a big help in McLean’s early development. He was very friendly with Rollins and played in the tenorist’s band as a youngster although by the time he attended the Benjamin Franklin High School, Rollins had just graduated. Feeling that he did not have enough comrades there, Jackie left after one year and switched to the Theodore Roosevelt High School in the Bronx. There he met Andy Kirk Jr., another musical influence. A strong one in fact and, just as Jackie acknowledged that Sonny Rollins was ‘eons ahead of me in music’, he also conceded that Kirk was even further ahead at that time. According to McLean, Bird used to go to Andy Kirk’s house whenever he was in the area. Kirk’s development as a youngster had been phenomenal and Jackie remembered that Sonny Stitt and Parker ‘used to sit in the room and hear him practice’.[3] Kirk had been a colleague and teacher of both Rollins and McLean but his story was ultimately one of promise unfulfilled. Already, in his teens, he was working on methods to expand and form a personal method of expression on Parker’s music, but Rollins began to develop at an almost unbelievable rate himself shortly after this. He went away for nine months and on his return his playing was ‘incredible’. Kirk told McLean about the way Rollins sounded and Jackie listened to the new Rollins, ‘and what he was doing bowled me over.’ After that Kirk began to slide into deep depression and heroin addiction and never played an instrument again.

Jackie had his first job in 1949, after high school graduation, at the Paramount theatre where large-scale music shows were performed. It was only a job as an usher which he had taken in response to pressure from his mother who told him she was not prepared to let him just ‘lay around the house all day, living the life of a musician’. Not, at least, until he could earn good money from that sort of life. This would indicate that he made little if any money from playing the saxophone up to that time. The job only lasted two weeks and later Jackie spoke contemptuously about ushering, wearing monkey suits at the Paramount. The ‘monkey suits’ were obligatory which may have been the main reason the job did not last. By his own admission Jackie was, at this time, a rebellious teenager as well as a young junkie and he found it difficult to keep himself and the suit clean and tidy and stand still for long periods of time. The job had its compensations, however, and while he was there he managed to hear concerts by Teddy Hill and Duke Ellington.

Many years later, Jackie was to claim that he and his friends were all hip junkies at that time but that most of the mothers on the hill went out of their way to give their children good manners. Jackie’s mother tried to protect him and make him behave well, pushed him towards what she regarded as suitable jobs and, all the time he lived at home with her, required him to get in at a respectable time of night, even if he had a jazz gig. She even managed to get her son to Agricultural and Technical College in North Carolina thinking it would get him away from the jazz life, jazz people and junk. Jackie found the campus life did not suit him at all, did not join in any of the activities and felt out of place for a whole year. And that was his first and last year: he headed back to NYC and carried on where he had left off. He jammed every minute he could, looked out for every jazz gig going in New York and played with whoever would let him sit in.

As there were so many important musicians growing up with him and attending the same schools, and so many influences to absorb and make use of, the way to becoming a musician was more or less mapped out for McLean by fate alone. There had been several early bouts of truancy to hear Parker playing and, a little later, Parker checked out the bars and cafes where McLean was playing and became more and more impressed by what he heard. But it was trumpeter Miles Davis who gave Jackie his first jazz gig, in 1950, while he was still a teenager and, a little later, his first record date. Bud Powell had arranged for his young friend to sit in with Miles’ band at Birdland where the trumpeter had a gig. Jackie, although nervous, arrived at the club, sat in with Miles and must have played fairly well as Davis invited him to come to his house the next day. He also asked Jackie if he had any written music and invited the young man to bring his compositions. ‘I don’t have them written but I can show them to you,’ Jackie replied, indicating that possibly due to his studies with Powell he was already relying heavily on his ear rather than written arrangements. So that was Jackie McLean in 1950, a little unsure of himself, as we shall see, and, it must be said, a little lazy. But he was, at this point, on the brink of a major career as a jazz soloist.

3. Out Of The Blue

On October 5th 1951 Miles Davis had a record date with Prestige in New York City. He had assembled a strong cast of sidemen with Sonny Rollins on tenor, Walter Bishop Jr. on piano, Tommy Potter, bass, the dependable, explosive Art Blakey on drums, and Jackie McLean. This was McLean’s first jazz session but not his first recording: that had been made in 1948 at the age of just sixteen with Charlie Singleton’s rhythm and blues band (Star 719). On Miles’ Prestige date he was the youngest man, playing alto sax, and raring to go. Sleevenote annotator Ira Gitler [1] says Jackie was still in his teens at this session but, if the May 17th 1931 birthday is correct, and it is, he was in fact just twenty years old. Gitler also mentions that this date was the first occasion when Prestige used the new microgroove long playing record format; up until this time all recordings had been 78 shellac discs with a playing time of barely three minutes. Dig (Prestige 7012) was one of the earliest chances that jazz musicians had to ‘stretch out’, to play solos that lasted four, five or even ten minutes in length. From the vantage point of the twenty-first century and digital compact discs, it seems strange to think that McLean’s first record date coincided with the start of the long playing vinyl record, a format that was as groundbreaking and important in its day as compact discs in the early 1980s.

This session, though Jackie’s first jazz record date, was not without incident. On arrival at the studio he was surprised and a little shocked to see Charlie Parker sitting in the control booth. ‘Oh my God,’ Jackie said, telling the story many years later, ‘’cause it made me nervous, you know, just to see him, because I idolised him so much; I think a lot of young musicians.'[2]

According to Miles Davis’ autobiography, Jackie was so nervous that he kept going over to Parker and asking him what he was doing there. Parker just smiled, told him he was playing really well and was cool because he understood what the young man was going through and how he must have felt.

Everybody sounds good on ‘Dig’, the opening track on the record; Miles thought that he played better on this session than he had for some time, possibly because he was addicted to heroin and felt quite relaxed. Looking at it from a slightly different angle, Sonny Rollins said on a YouTube item posted on the internet that he felt that he and Jackie provided the hard bop element on that record that helped to put Miles back in favour with his followers, the hipsters of NYC. Apparently, according to Rollins, many of them had been alienated from Davis due to his Birth of the Cool sessions recorded in 1949–50, feeling that this music was too slight and ephemeral to be taken seriously and not the best representation of Miles Davis. Whether Miles agreed or not is open to question but he did in fact move more towards bop and hard bop in his music throughout the 1950s.

In his sleevenote Ira Gitler makes much of the growing partnership between Miles and Sonny Rollins but Jackie’s first solo is quite brisk and confident; he opens with a typical Parker attention-grabbing phrase but goes on to play an assured-sounding bop solo. Whatever he was feeling with Parker sitting there listening, his solo playing on the the rest of the session also sounded bright and fairly confident. Charles Mingus had gone with Miles to the studio that day and he played bass on ‘Conception’, a piece that appeared on a different record of that name, but the regular bassist, Tommy Potter, played on all the other selections. With so much going on, seasoned veterans visiting or occasionally playing, Jackie could well have been overwhelmed and unable to play much at all. He was in fast company with Miles, Rollins, Blakey and Walter Bishop but his solo on ‘Denial’ oozes confidence and brio. Even if the language is mainly Parker, at least he has a thorough understanding of it and can play it well. But there are, in fact, little tell-tale signs of the emerging Jackie McLean sound to be heard if we listen carefully. He was already playing slightly behind the beat and that rather personal, almost aggressive tone of his was just starting to assert itself. ‘Bluing’, a typical Miles line of the time has Jackie following a strong Rollins solo with a blues-flecked statement that is strong and inventive and, once again, indicates a personal sound fighting to come through a Parker-styled delivery. ‘Out of the Blue’ is in lively, happy mode although the tempo is steady, not too fast and not too slow. Jackie sounds relaxed at last and his solo, inventive and flowing, just tumbles out.

He was playing well and the session ended with some good music on the tapes but the next recording session with Miles had other problems for McLean to face up to. It was made in New York on May 9th 1952 at the WOR Studios for Blue Note Records, the best and most respected of the independent record labels and Miles had lined up a sterling bop cast of musicians headed by trombonist J. J. Johnson. The rhythm section consisted of pianist Gil Coggins, bassist Oscar Pettiford and drummer Kenny Clarke. It is immediately apparent that Jackie sounds more relaxed here than on his first date and is obviously not overawed, or indeed overshadowed, by his illustrious colleagues. ‘Donna’, a fast bop line, was written by McLean even though it is the same song as ‘Dig’ which was credited to Davis on the Prestige disc. McLean is very assured here and whips through his solo segments with no hesitation whatsoever. If he was reluctant to make the effort to learn to play standards, ‘Woody ’n’ You’ he knew as it was a bop staple and his solo here leaps out of the speakers, his sound strong and tensile, bluish-grey in colour, as he fashions his own variations in a tone that was steadily becoming unique and personal. Miles wanted to record ‘Yesterdays’ and ‘How Deep Is the Ocean’ but there were problems: Jackie couldn’t get his solo right and claimed that he didn’t know the tune of ‘Yesterdays’. Miles became angry and cursed him out but things did not improve. When asked what was the matter with him, Jackie said that those tunes were old and from another period and he was a young guy. Miles put him right saying that music had no periods, music is music. ‘I like this tune, this is my band, you’re in my band, I’m playing this tune, so you learn it and learn all the tunes, whether you like them or not. Learn them.’

In the end Jackie sat out those two tunes and did not play on them but it caused something of an issue between him and Davis. Davis tried to persuade him that he must work hard and learn all the music he was likely to be called on to play and he did make the effort later and became a consummate ballad player and interpreter of standard songs. It was his early nervousness and insecurity that had caused him to hold back on standards, similar behaviour in fact to his nervous reaction to finding Charlie Parker in the studio listening to him play. In any event, in spite of the slight rift caused by this incident, they continued to play music and hang out together during this time.

* * *

It was a hectic and in many ways troublesome four years for McLean between 1951 when he had his first gig with Miles Davis and 1955 when he began to find more confidence in his own ability and a mature approach to his music. At his very first gig with Davis in 1951 at Birdland, one of the leading jazz clubs in NYC, Jackie had played half a solo and suddenly rushed offstage, out into the backyard and been violently sick into a garbage can. It was partly nervousness and partly the desire to do well in a band that contained leading musicians like Rollins, Kenny Drew on piano, Percy Heath on bass and Art Blakey behind the drums. Miles, wondering what was happening, had followed him out to the yard and checked to see that he was all right and able to continue playing. He was, after cleaning himself up and receiving a look of disgust from the owner of Birdland, Oscar Goldstein. Davis speculated that part of Jackie’s problem was drug addiction because the young man had become a heroin addict when still very young.

‘It came on the scene like a tidal wave,’ Jackie explained, years later. ‘I mean it just appeared after World War Two some kind of way.’ He claimed that he and his fellow victims did not know, they just did not understand what they were getting into; they were targeted by the drug barons and pushers of the time, much in the same way that young people are targeted today; the drug barons have become greedier and greedier, ever pushing for larger communities of vulnerable victims and feeding on their ignorance and weakness.

McLean was honest enough, though, to point out that part of his own reason for experimenting with the drug was because his hero Charlie Parker was an addict. He also pointed out that almost all the young musicians of the day idolised Parker and thought that if he played better when he was high so could they. McLean was, by his own admission, to endure fourteen years of struggling to make a living and support a family – his wife Dollie, two sons and a daughter – while having an addiction to heroin. Somehow he managed to play the music he loved and support everything, including his habit. Jackie had met Clarice Simmons, known to her friends as ‘Dollie’ at a party in the Bronx. She belonged to a strict West Indian family and unlike other women of Jackie’s acquaintance she knew nothing about the jazz life or jazz musicians generally. They married in 1954 and Jackie assumed responsibility for her two young children from a previous marriage.[3]

One constant that stays with McLean all through the early years of his studies as a saxophonist and through his first years as a professional musician from around 1949 until 1955, is his relationship with Charlie Parker. Seen in perspective and up close, this can only be considered as both a blessing and a curse. But his admiration for the older man and Parker’s somehow instinctive, intuitive realisation that Jackie was to be a major figure in the jazz of the future, drew them together and made them forever watchful of each other’s progress.

There were often occasions when relations were strained between the two men, usually because of Parker’s pawning of instruments when he was broke and desperate for yet another ‘fix’. Sometimes it was Jackie’s horn that Parker pawned, sometimes it was an instrument that the two musicians had rented between them, but the number of times it happened riled McLean. Parker, often broke or in debt, rarely had a horn in his possession and borrowing Jackie’s was probably an everyday occurrence unless they rented. And there were many times when Parker used McLean’s horn but did not return it and the instrument ended up lost or stolen. Mostly though, Jackie seemed to bend over backwards to forgive Parker or at least to see only the good in him.

‘He was always trying to look out for younger musicians,’ McLean recalled years later. ‘At least that’s the way I felt, you know.’

Parker also excelled in borrowing or extracting money from young McLean, sometimes taking it out of his pocket. He would ask Jackie how much money he had and how much he needed and ask him for the rest after McLean had stated a low figure. On some occasions, he put money back and even put back a lot more than he had taken, as Jackie recalled years later.[4] Although there were very many times that rented horns found their way into pawn shops, when he had money Parker would redeem them himself. It was the other times that Jackie found difficult.

The relationship between the two men had progressed from one in which Jackie was an admiring fan, a hero worshipper who had been flattered and delighted to be invited to sit in for the great man at a gig, to that of two musicians who often heard each other play and started to hang out together. But Jackie had seen several sides to Parker in those years, the older man a chameleon who changed colours from kind, thoughtful friend and mentor to heroin-addicted hard-case who would, in his colleague Dizzy Gillespie’s words, ‘sell his grandmother for a fix’. Parker at his worst was someone that even his closest friends kept their distance from.

A few days after an incident in NYC, when he showed his annoyance at Bird for losing yet another horn, Jackie read that Charlie Parker was dead. He was devastated and filled with remorse because he had snubbed Parker the very last time he had seen him, something that would leave a scar for many years after the event. Like all the modern jazz musicians he felt the loss deeply but, unlike many of the others, he had enjoyed a special relationship with the great alto saxophonist. He could not have realised it then but at that moment, the moment of Parker’s death, he came out from under the giant shadow of Bird’s all-embracing influence and began to develop as a soloist in his own right.

It was 1955, his playing was becoming ever stronger and ever more distinctive and he was on the threshold of a career that sent into reverse the usual jazz icon story: learn to play, play brilliantly, become famous, become addicted and die ridiculously young of drink, addiction and dissipation. Jackie got into the addiction very early in his life, began to play brilliantly, then became famous and multi-talented and turned into a respected educator. In 1955 he was poised, a little unsure of his direction but confident in the harsh environment of the recording studio and standing precipitously on that threshold.

4. Starting As He Meant To Go On

The more mature, confident alto saxophonist that Jackie McLean became began to make his mark and get himself noticed as early as 1955. He was twenty-four years old and beginning to get a reasonable number of gigs and to have recording opportunities. His development was fairly brisk and certainly impressive and by the time he went into the studios to record on two extended tracks on Miles Davis’ Sextet LP of August 5th 1955 he was confident and self-assured. The two tracks, ‘Minor March’ and ‘Dr. Jackle’ were written by him and he takes the first solo on the former. Miles did not often use other soloists’ compositions from within his own band or even outside it and when he did they were usually from seasoned contributors.

Jackie demonstrated his familiarity with, and ability to compose in, the standard bop language of the day. ‘Dr. Jackle’ is a rather complex line with, on this version, Milt Jackson on vibes leading the solo sequences, followed by Miles sounding calm, cool and collected. Jackie picks up the tag end of Miles’ solo and is soon confidently spewing out hot flames of bop improvisation, double timing like a veteran and generally producing a lively and very impressive solo. The Parker mannerisms are still there to be sure and the phrasing is Parker bop too but McLean was building a professional solo style while openly admitting to taking a lot from Parker in his method of constructing solo lines. At this stage of his development he was well advanced as a modern soloist with the ability to construct solos at just about any tempo, play clean lines and ride on a good rhythm section. Individuality would come but it was not overconspicuous in the August of 1955.