Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Northway Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

Among the great American modern jazz saxophonists, Mobley had been the most unjustly neglected – the truly forgotten man. Yet he played and recorded prolifically with the greatest legends of his era such as Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Lee Morgan, Johnny Griffin and Art Blakey, helping to create some of their finest work. His best recordings are classics, characterized by an instantly identifiable sound and style, and constant musical inventiveness. But his loner personality made him his own worst enemy, many of his records remained unissued in his lifetime, and he died forgotten and destitute. Now, at last, most of his recorded legacy is available on CD and he is recognized as one of the major figures of modern jazz. This book provides a detailed introduction to the music and a reassessment of Mobley's contribution to jazz.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 266

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

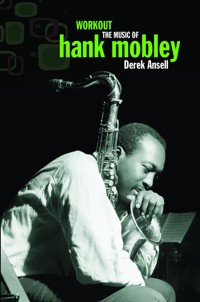

WORKOUT

The Music of Hank Mobley Derek Ansell

Workout first published by Northway, 2008; in ebook format, 2014. © Derek Ansell 2008.

The right of Derek Ansell to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. Cover photo of Hank Mobley at the Rudy Van Gelder Studio, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, on March 18th 1966 for his A Slice of the Top recording session. Photo by Francis Wolff, © Mosaic Images. The publishers acknowledge with thanks the generous assistance of Michael Cuscuna. Visit www.mosaicimages.com for information on obtaining prints of Francis Wolff photographs. Cover design by Adam Yeldham of Raven Design.

Ebook conversion by www.leeds-ebooks.co.uk

The author, Derek Ansell

Derek Ansell has lived in Berkshire, England, for the past forty years. He writes regular reviews of live jazz and classical music for magazines and newspapers and has contributed more than two hundred articles and numerous interviews, record and book reviews to Jazz Journal International. His book about the music and life of Jackie McLean, Sugar Free Saxophone, was published by Northway in 2012.

He is the author of several novels including The Whitechapel Murders, a fictional account of the notorious Jack the Ripper murders in London in 1888, and My Brother’s Keeper published in 2014.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Introduction

1.Early Messages: 1954–552.A Leader on Records3.Unearthing the Rarities4.The Jazz Life5.Poppin’ and the Curtain Call Session6.Soul Station7.Working Out8.The Turnaround9.Consolidation10.Europe11.The Enigma of Hank Mobley12.Coming Home13.A Slice of the Top14.The Last Years15.Straight No Filter16.The LegacyEpilogue

Notes

Records

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

My thanks are due to David Nathan at the National Jazz Archive at Loughton, Essex, for digging out some features on Hank Mobley from the 1960s and 1970s. These articles from Jazz Monthly, Jazz Journal and Melody Maker were very helpful.

The editor and staff at DownBeat magazine provided a copy of the one important interview Hank gave, to John Litweiler in 1973, which opened a few doors to his character and motivation. They also gave permission to quote from this interview. Simon Spillett, a tenor saxophonist who claims Mobley as one of his favourite tenor players, not only helped with permission to quote from his articles on Hank in Jazz Journal International in 2003 and 2004 but also, very kindly, sent me copies of tapes with music not generally available and known only to a few collectors. I have also appreciated the support of Michael Cuscuna and the staff at Mosaic Records.

My own collection of Mobley records is fairly substantial but some gaps were filled when Eddie and Janet Cook sent me new Mobley reissues to review for Jazz Journal International, including the rare Debut sessions now available on Jazz Door Records. Information gleaned from record sleeve notes and reviews, in particular those by John Litweiler, have all proved useful.

My sincere thanks to all concerned.

Derek Ansell

INTRODUCTION

Hank Mobley was unique. He was much admired by other musicians, many of whom rated him as one of the very greatest modern stylists, and a tenor saxophonist who sold more records than almost anybody else on the Blue Note label. Yet he still managed to attract a lot of flack, at best, from critics and jazz commentators who undervalued his solo strengths and contributions to modern jazz and, at worst, from those who regarded him as obscure and unimportant.

A jazz musician who recorded twenty-five LPs as a leader for one independent record label and more for other companies can hardly be called obscure. Add in numerous sideman appearances in the 1950s and 1960s – far more than most musicians in his sphere, and a face that was well-known from liner photographs and even made the cover shot of The Blue NoteYears: The Jazz Photography of Francis Wolff and you have a significant musician. And yet Hank Mobley was consistently underrated, unfavourably compared with some of his more flamboyant contemporaries of the day and never really given his due as a consistently inventive and often innovative tenor sax soloist and a composer of considerable skill and imagination.

Should you wish to know more about the major jazz musicians who made their names in the 1950s and 1960s, you will find plenty of books about John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins and other key figures of the bop and hard bop movements of that time, but until now there has not been one about Hank Mobley. Why? The general consensus seems to be that Coltrane, Rollins and even lesser talents such as Johnny Griffin, possessing hard, edgy tones in the fashion of the day, all tended to overshadow Mobley’s quieter approach.

The hard bop sound was certainly used and developed by those musicians and you could hardly ignore the spectacular playing of Rollins and Trane, but it really wasn’t that simple, as I attempt to show over the following pages. Partly, of course, it was a question of influences: Rollins from Coleman Hawkins; Trane from Hawk and Lester Young; Stan Getz from Lester Young. Getz is a good example: tremendously popular, he developed a modern, Parker-influenced variation of Young’s approach to tenor playing but, because the earlier styles and sound were so well known to jazz aficionados, he was quickly accepted and soon winning polls and filling venues. Hank Mobley, on the other hand, had a light, lyrical sound that was all his own, not like that of anybody who had gone before, even though his style descended directly from Charlie Parker.

Jazz, for all the innovation, excitement and boundary pushing by key musicians over the years has, curiously, always managed to breed ultra-conservative followers. Jazz fans tend to stick to what they know and like and take slowly, if at all, to new ideas and styles. It took a long time for most fans to adjust to the modern jazz of Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, and even longer for them to accept Thelonious Monk, that iconoclastic genius of modern piano. It took years for the innovations of Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor and Eric Dolphy to become absorbed into the mainstream and many jazz enthusiasts have still not made the final transition. Most jazz critics and writers cannot agree about anything much and fans tend to stick with a particular style and era to the exclusion of all else.

It is true to say that all jazz enthusiasts have a particular favourite jazz era, the one in which they first started to listen to the music. This overrides almost every other consideration for most people. I have yet to meet anyone who is exempt from this rule, myself included. Older people often have a lifelong love of New Orleans jazz that seldom extends beyond the swing era of the 1930s and early 1940s. The big band era is everything to some batches of enthusiasts and they have little time for other jazz periods. Others, including many prominent critics, embraced the bop revolution of the 1940s, happily congratulating themselves on their powers of understanding, but could never quite come to terms with the minor revolution of the 1960s avant-garde movement. Yet more are totally overwhelmed by the cool music of the West Coast school in California and have little or no time for any other style. Show me someone who embraces the best of jazz and the greatest musicians from New Orleans to California by way of Chicago and New York City, who can and does enjoy a wide range of jazz by Armstrong, Beiderbecke, Young, Hawkins, Parker, Gillespie, Monk, Coltrane, Rollins, Mobley, Coleman, Dolphy, Taylor (Cecil, that is) and many others, and you will be showing me a real jazz enthusiast, someone who understands the true, ever-changing, ever-developing, constantly evolving nature of this music. But there are precious few of them around.

Hank Mobley was just one of many who missed out on the accolades and the big time and the fame and fortune. Partly, his ultimate, overall failure to make it was his own fault; it happened for many other reasons too. This is his story.

1

EARLY MESSAGES

1954 – 55

Hank Mobley seemed to arrive on the jazz scene in New York City from out of nowhere, with a sound and style all his own. Where others had taken years of preparation, rehearsal and work in various rhythm and blues bands, there was Hank, with little playing experience behind him, fully formed and raring to go. He was one of a relatively short list of great tenor saxophonists; innovative, creative jazz musicians who not only had a distinctive sound but contributed immensely to the development and evolution of the music.

Consider the most important musicians on the tenor saxophone. Coleman Hawkins came along first and made his mark as a distinctive soloist. For many years Hawkins was the major influence and source of inspiration to all jazz musicians who played tenor sax and the most important of them took their lead and general stylistic approach from him. Then, some years later, Lester Young showed that a radically different approach was possible. Many years after that, Sonny Rollins came along with an updated approach to the Hawkins concept and a little while later John Coltrane appeared with a sound and style that were utterly unique. Although his style had roots in what Hawkins and Young had done before, it was completely and utterly new and original. So new and original, in fact, that it took many commentators and people who thought they knew a thing or two about jazz at least ten years to appreciate the man’s importance. In the 1960s, briefly, Albert Ayler offered yet another unique voice with a sound and style that were both radical and, in their reliance on old folk strains, fairly conservative.

The odd man out was Hank Mobley. He started to play with big name bands in 1951 when Max Roach hired him but, from then until his premature death in May 1986, he was creative, original, often brilliant, but consistently underrated by observers and critics of the music.

Those are the bare facts. To examine the reasons why he was so important we need to study his music. Fortunately he recorded prolifically: twenty-five albums as a leader for Blue Note between 1954 and 1970 but, after including other labels such as Prestige, Savoy and Roulette, the total is more like thirty-four. Alfred Lion, the founder of Blue Note Records, recognised the innovative skills and competence of Mobley, who soon became a leader on records. But most of the rest of his career was spent as a sideman in other people’s bands and that gives us our first clue to the personality and character of Hank Mobley, the man and the musician.

* * *

Mobley was never a forceful or assertive character. We know from other musicians with whom he worked, and from observers of the jazz scene in the 1950s and 1960s, that he was always something of a recluse, going out to work in various combos and orchestras, playing his part and then returning home.

During the intervals at clubs he would disappear out to the car park or street and sit smoking in his car until it was time to play again. Writing his obituary in the September 1986 edition of Jazz Journal, Dave Gelly told of the time he visited the USA in 1963 and heard Hank play at the Five Spot Cafe in a combo with pianist Barry Harris. In conversation with Gelly, the pianist said: ‘Don’t bother trying to talk to Hank. He doesn’t even talk to me. He’s sitting out there in his car and he won’t come in till it’s time for the next set.’ Harris pointed out of the window and Gelly saw a shadowy figure sitting in an old, beaten-up Buick parked at the kerbside. Like some professional actors who hide behind a part and can bellow out the lines of King Lear or Henry V on-stage and then come off and be almost inarticulate off-stage, Hank could play with the very best jazz musicians on equal terms but once off the bandstand he became quiet, reticent and very introverted. Gelly’s Jazz Journal obituary also pointed out that Mobley’s sound, live, was something to marvel at, especially for those who were sitting close to the bandstand and hearing it direct. Although the recordings for Blue Note engineered by Rudy Van Gelder were very good and he probably produced the closest thing to a natural jazz sound on records, he did have his own idiosyncratic methods, adding a little echo and, as Gelly put it, he ‘boosted Mobley’s volume in relation to the rest of the band . . . In person the sound shrank to a conversational level. It was laconic and somehow beady-eyed, a cool tone for a cool head.’

Van Gelder always jealously guarded the secrets of his methods of recording and the details of the equipment he used, even from fellow-professional recording engineers, so we are unlikely ever to know exactly what was added or subtracted from the natural sound of musicians such as Mobley. We can be sure, however, that the engaging, light blue gauzy sound that we hear on the best recordings was enhanced by the natural balance obtained in good clubs with light amplification; a situation that seems lost beyond recall in these days of massive over-amplified PA sound systems.

If booked to play in a band Mobley would always give his very best but if, as sometimes happened, he was distracted by another soloist, or found on arrival at the gig that another musician that he hadn’t known about had been booked alongside him, he would retreat into his shell and play as little as possible, doing just enough to fulfil his obligation to the bandleader but shunning the chance to solo often, if at all.

He was, certainly, reticent and quiet most of the time, living for his music but unwilling, it seems, to take on the responsibilities of leadership. This must account, in part, for some of his early failure to attract attention or to show just how good a soloist he was, for his appearances could be limited by his own reservations and attitude. Early on in life, however, Mobley had decided that he wanted to be a musician.

* * *

He was born Henry Mobley in Eastman, Georgia, on July 7th 1930, but his parents moved to Elizabeth, New Jersey when he was still a small child. It was a musical family. Hank’s grandmother was a church organist and his mother played piano. He also had an uncle who played piano and other instruments and there was always plenty of piano music about the house. At the age of eight he started taking piano lessons but he did not become serious about music until the age of sixteen, when he developed an interest in the saxophone. He managed to get a long school-holiday job in a bowling alley and saved money to buy a sax. When he had saved enough for his purchase, he was dismayed to find that the dealer had gone on holiday for a month. The young Hank was pretty single-minded and determined, however, and turned a problem to his advantage. As he told John Litweiler in his interview for DownBeat magazine in 1973, he got himself a music book and by the time the dealer returned had learned the whole instrument:

‘All I had to do was put it in my mouth and play . . . I’ll tell you, when I was about eight they wanted me to play piano, but I wanted to play cops and robbers. But when I got serious the music started coming easily.’1

At this time he was studying carpentry and auto mechanics and was, by his own admission, a nervous wreck from studying to be a machinist. Fortunately, the shop teacher was also a trumpet player and he heard Mobley play the Lester Young solo from ‘One O’ Clock Jump’, note for note. He said to the youngster: ‘There’s no room out there for a black machinist. The way you play saxophone, why don’t you study that?’ And that is precisely what Mobley did. He left the machine shop that year and, as he told Litweiler, ‘I just put on my hip clothes and went chasing women and going to rock and roll things.’

His uncle, Dave Mobley, gave him advice that he must have taken very seriously, for it helped to shape his development into a particularly individualistic tenor soloist. He recommended listening to Lester Young and then to Don Byas, Dexter Gordon and Sonny Stitt, and ‘anyone who can swing and get a message across’. He also told him, ‘If you’re with somebody that plays loud, you play soft, if somebody plays fast, you play slow. If you try to play the same thing they’re playing you’re in trouble.’ This advice came when Hank was just eighteen years old and he certainly took it to heart and never forgot it.

At the start of the 1950s, Mobley became a professional musician. He was already working in rhythm-and-bluesman Paul Gayten’s band and, soon after that, he added a gig as a member of a Newark club’s house-band, together with pianist Walter Davis Jr. The club presented weekly guest front-liners from New York, and Mobley, who must have learned fast, soon found himself supporting and playing alongside the likes of Billie Holiday, Bud Powell, Miles Davis and a host of top soloists. The need to think on his feet and the determination to take Uncle Dave’s advice must have been the origin of his technique, later developed to a fine art, of making lines breathe when he wanted them to, and not when the music dictated it. He fashioned a rhythmic ability like nobody else’s; his rhythmic flexibility always got him out of trouble and whatever was played, no matter how complex the line, he found ways to make everything fit for him and come out right. Good examples can be heard throughout his recordings, particularly his sterling sets in the mid to late 1950s and his masterworks in the early 1960s.

It was while Hank was working at the Newark club that Max Roach was booked to front the house-band. This was a weekend in 1951; Roach promptly offered the tenor player a job in his regular band. As Hank put it to John Litweiler:

‘I was just twenty-one. We opened in a place on 125th Street in Harlem; Charlie Parker had just been there before me, and here I come. I’m scared to death – here’s Sonny Rollins, Jackie McLean, Kenny Dorham, Gerry Mulligan, just about all the young musicians came by there.’

Scared he may have been, thrown into the deep end by Roach’s recognition of an unformed but vital musical talent, but he soon became accepted on the New York scene and, unlike most musicians before him, he did not have to make the agonising decision of moving alone to NYC and taking his chances with all the competition. He had been taken there from Newark by a major leader with a ready-made gig lined up. Soon Mobley was working regularly in NYC clubs and Roach recorded ‘Mobleyzation’, his first composition. By the time the combo broke up, Mobley was already established and never short of work. It was during this period in the early 1950s that he was called on by bassist Oscar Pettiford, who recruited for Duke at that time, to sub in the Duke Ellington Orchestra for two weeks. ‘Jimmy Hamilton had to have some dental work done,’ Hank recalled in 1973. ‘I didn’t play clarinet but I played some of the clarinet parts on tenor.’ Mobley remembered hanging out with Paul Gonsalves, Willie Cook and Ray Nance. ‘We were the four horsemen, but nobody would show me the music and it was all messed up. So Duke would say, “A Train”, and while I was fumbling for the music the band had started. Finally Harry Carney and Cat Anderson helped me straighten it out.’

There was plenty of work for the young saxophonist. He worked the clubs and studios of NYC, took part in a second tour with Paul Gayten’s band and in the summer of 1953 was with Clifford Brown in Tadd Dameron’s band at the Club Harlem in Atlantic City. Meantime, Max Roach, then in California, was looking for really good musicians for a new, all-star quintet. He tried to reach Mobley by telephone but was unable to locate him. He did make contact with Clifford Brown and so history was made with the beginning of the Clifford Brown–Max Roach Quintet. Had the drummer managed to find Hank, he might have been the tenor player with the group rather than Harold Land and later, briefly, Sonny Rollins. Instead, Mobley joined up with Dizzy Gillespie and played in the trumpeter’s big band for a time. That lasted for a year and then there was a new turning point in his career when he joined pianist Horace Silver.

Silver had a quartet with an engagement at Minton’s Playhouse, one of the places where bebop, or modern jazz, was first played. He had Doug Watkins on bass, Arthur Edgehill on drums and in 1954 Mobley became his front-line soloist on tenor saxophone. As Hank told Litweiler, ‘On weekends Art Blakey and Kenny Dorham would come in to jam, ’cause they were right round the corner.’

This was the beginning of a new and superb quintet, which would become the Jazz Messengers, the first of a series of bands with this name but with ever-changing personnel, and it would go on into the 1980s under the leadership of drummer Art Blakey. But in the beginning it was a cooperative unit and had no name. Horace Silver was the best-known musician at the time and the first studio recordings, originally released as two ten-inch LPs and later combined into a twelve-inch, for Blue Note, were billed as Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers. The cooperative that grew out of the Minton’s engagement consisted of Dorham, Mobley, Silver, Watkins and Edgehill. They would use their individual names to get gigs and as soon as one of them landed a job, he would contact the others and they would all play. After a time Edgehill dropped out and Blakey became the cooperative drummer on a regular basis. Mobley said: ‘Horace’d get a job, or Art or Kenny would get a job; we’d split the money equally; I think that’s where the cooperative started.’

On November 13th 1954, the first sessions were recorded for Blue Note of what became arguably the best single recording by the original Jazz Messengers. The title of the two ten-inch LPs was Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers and the music recorded then and at the second session on February 6th 1955 marked the start of the most famous academy of hard bop ever. The Jazz Messengers lasted through four decades and only expired on the death of their leader Art Blakey. But in 1954 the band was very much an equal shares cooperative, nominally led by the pianist, and their first, and arguably their best-ever tenor saxophonist, was the young, up and coming Hank Mobley.

It was at this point that Mobley should have become reasonably well known and appreciated but recognition and praise for his playing were slow to arrive. The LP Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers, when it was eventually released as a twelve-inch album, drew praise for Silver, Dorham and the rhythm section but most commentators singled out Mobley as the weakest member of the combo. Perhaps it was due to his relaxed sound and unique manner of phrasing. Although Hank’s style was unformed in those early days he still managed to sound like nobody else but himself. His unusual way with rhythm was unexpected and his stylistic influence, such as could be detected, was directly from Charlie Parker, while at the time, virtually all tenor saxophonists were playing like Lester Young or Stan Getz. Only the very young Sonny Rollins was beginning to make a stir with a more robust sound that was, in effect, a modern variation of Coleman Hawkins filtered through the innovations of Charlie Parker. Right from the beginning, Mobley was a soloist who ploughed his own furrow and virtually ignored what was being played by other musicians on his instrument.

Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers established Silver as a combo leader and composer; he had written all the material except for Mobley’s ‘Hankering’. The quintet worked successfully for about a year and a half as the Jazz Messengers and as a cooperative unit. Long before their time together ended, however, Blakey had begun gradually to assert himself as the unofficial leader and it is his voice that is heard making all the announcements on the excellent two-CD set The Jazz Messengersat the Café Bohemia, recorded on November 23rd 1955.

Hank’s technical proficiency was already assured by the time he recorded with the first Messengers group in 1954–55. His tenor sax floats out of the ensemble on ‘Stop Time’ as easily and naturally as Lester Young’s with Basie in the 1930s, but the sound is not the same. Where the vast majority of tenor players of the time sounded like Lester, Mobley already had his own thing developing. To put it as simply as possible, his sound was softer and rounder than that of the hard boppers, but harder and more resonant than Stan Getz, Richie Kamuca, Bill Perkins, Zoot Sims and the rest of Young’s stylistic descendants. And his lines were Parker-inspired hard bop, albeit with a unique and, many would say, idiosyncratic attitude towards rhythm. He would cut across bar lines and somehow squeeze as many notes as he wanted into a given sequence and always make it come out sounding right or, at least, right for him.

On the liner notes to Poppin’, a 1957 recording first released on LP in 1980, Larry Kart described Mobley’s tone as ‘a sound of feline obliqueness – as soft, at times, as Stan Getz’s but blue grey, like a perpetually impending rain cloud’.2 It is a good description and one that holds for a lot of Mobley recordings. It was also Larry Kart who first pointed out, on those same liner notes, that, on the Miles Davis composition ‘Tune Up’:

‘The apparently simple but tricky changes pretty much defeat Art Farmer and Pepper Adams; but Mobley glides through them easily, creating a line that breathes when he wants it to, not when the harmonic pattern says “stop”.’

It was this quality above all others that set Mobley apart and made him a true innovator, a musician who, like Young, Parker, Coltrane, Coleman and a very few others, made his own rules and placed his musical statements in the slots he created for them, whether they fitted the rules of music or not. One of his best early solos on Horace Silver and the Jazz Messengers can be heard on ‘Creepin’ In’, a slow atmospheric piece in a minor key which has all the quintet members stretching out luxuriously.

A few weeks after Horace Silverand the Jazz Messengers was recorded, Hank had the opportunity to make his first LP as a leader. On March 27th 1955 he recorded The Hank Mobley Quartet, a ten-inch record on which he used his colleagues from the Messengers except for Kenny Dorham. As early as this, it is noticeable that Mobley was a gifted composer and all except Cole Porter’s ‘Love for Sale’ are the saxophonist’s originals. ‘Hank’s Prank’ is a well-constructed ‘I Got Rhythm’ variation which features complex, lively solo work from the leader and a strong Silver statement. It is immediately apparent that these are not mere frameworks for soloists to blow on; they are fascinating original compositions, particularly ‘My Sin’, a yearning slow ballad, and the delightful minor opus ‘Just Coolin’’. Such was Mobley’s ability as a composer that he would often put new compositions together in the studio, in the course of a recording session.

This LP was, according to Hank himself, his best early recording and, as noted by Bob Blumenthal on the liner notes to the Mosaic six-CD set of the saxophonist’s 1950s leader dates:

‘significant preparation had preceded the actual visit to Van Gelder’s studio. The command of his instrument, his invention and attractive lines such as ‘Walkin’ the Fence’, ‘Avila and Tequila’, and the ripe melody of ‘My Sin’ all combine to suggest a very well-rounded modern jazz musician as early as 1955.’3

If I had access to a time machine, my first port of call would be the Café Bohemia on the night of November 23rd 1955. By this time, the original Jazz Messengers quintet had been recording and playing live dates regularly and had shaken down to one of the very best modern jazz combos around. Alfred Lion recorded the band for Blue Note with his regular recording engineer, Rudy Van Gelder. Portable equipment was set up in the club and it recorded just about every note played by the band on that evening. Mobley was in great form, as he often was by this time, and so too were Dorham, Silver, Watkins and the irrepressible Blakey.

With the passage of years it now seems a little strange hearing again Blakey’s opening announcements from the Bohemia stage, especially when he mentions ‘one of the youngest and finest bass players on the scene: Doug Watkins’, and later, ‘a new star on the modern jazz scene, Hank Mobley’. Hank was just twenty-five at that gig and Watkins, a superb bass player destined to die tragically young in a car crash seven years later, just twenty-one. But there can be no argument with Blakey’s assertion that they were ‘having a cooking session here tonight, putting the pot on in here’.

Some of the very finest hard bop ever recorded can be heard on the two volumes of The Jazz Messengers at the Café Bohemia. Indeed it was some of the very first hard bop, following the earlier Art Blakey Quintet, recorded at Birdland in February 1954. This set is a further refinement of the style created simultaneously by Blakey working with Clifford Brown and Lou Donaldson, and by Max Roach, who was also working with trumpeter Clifford Brown. If the Birdland set with Brown was a statement of intent, full of fire and fury, headlong tempos and relentless swing and some gorgeous lyricism – a virtual definition of the new hard bop – then the Café Bohemia sets are a consolidation; there is a feeling of control and almost of relaxation throughout these performances. It is as if Blakey and company are telling us that the new music is often hard and fast and furious but it is also warm, melodic and lyrical. Only the uncompromising approach and the near equal status of the rhythm section to the front line has changed and changed for ever. Few rhythm sections would be shrinking violets, content to provide a soft-focus, light beat in the background, after these recordings were heard and noted.