7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

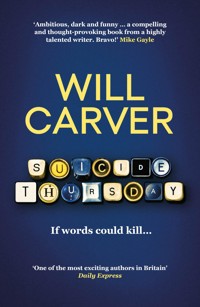

A disenchanted man struggles to get beyond the first chapter of the books he's writing, and to separate fact from fiction in his own life. His friend's suicide changes everything … The mind-blowing, heart-rending new thriller from cult bestselling author Will Carver. 'Ambitious, dark and funny … a compelling and thought-provoking book from a highly talented writer. Bravo!' Mike Gayle 'One of the most exciting authors in Britain' Daily Express 'Unflinching, blunt and brutal, Carver's originality knows no bounds. Simply brilliant' Sam Holland ___________________________ Eli Hagin can't finish anything. He hates his job, but can't seem to quit. He doesn't want to be with his girlfriend, but doesn't know how end things with her, either. Eli wants to write a novel, but he's never taken a story beyond the first chapter. Eli also has trouble separating reality from fiction. When his best friend kills himself, Eli is motivated, for the first time in his life, to finally end something himself, just as Mike did… Except sessions with his therapist suggest that Eli's most recent 'first chapters' are not as fictitious as he had intended … and a series of text messages that Mike received before his death point to something much, much darker… ____________________________ 'Gave me nightmares … I loved it' S J Watson 'Brutal and brilliant' Lisa Hall 'Challenging, perceptive and unexpectedly enlightening' Sarah Sultoon 'Will Carver is a unique writer. I loved Suicide Thursday' Greg Mosse 'A smart, stylish writer' Daily Mail 'Carver's trademarked cynicism and contemptuousness run rampant here … [a] dark, dangerous novel' Jack Heath 'One of the most compelling and original voices in crime fiction' Alex North Praise for Will Carver 'Deliciously fresh and malevolent story-telling' Craig Sisterson 'Weirdly page-turning' Sunday Times 'Laying bare our 21st-century weaknesses and dilemmas, Carver has created a highly original state-of-the-nation novel' Literary Review 'Arguably the most original crime novel published this year' Independent 'This mesmeric novel paints a thought-provoking if depressing picture of modern life' Guardian 'Most memorable for its unrepentant darkness…' Telegraph 'Unlike anything else you'll read this year' Heat 'Incredibly dark and very funny' Harriet Tyce 'Wickedly fun' Crime Monthly 'Will Carver's most exciting, original, hilarious and freaky outing yet' Helen FitzGerald 'Vivid and engaging and completely unexpected' Lia Middleton 'Dark in the way only Will Carver can be … oozes malevolence from every page' Victoria Selman 'Move the hell over Brett Easton Ellis and Chuck Palahniuk … Will Carver is the new lit prince of 21st-century disenfranchised, pop darkness' Stephen J. Golds 'Carver truly at his best' Sarah Pinborough

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 426

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Eli Hagin can’t finish anything.

He hates his job, but can’t seem to quit. He doesn’t want to be with his girlfriend, but doesn’t know how to end things with her, either. Eli wants to write a novel, but he’s never taken a story beyond the first chapter.

Eli also has trouble separating reality from fiction.

When his best friend kills himself, Eli is motivated, for the first time in his life, to finally end something himself, just as Mike did…

Except sessions with his therapist suggest that Eli’s most recent ‘first chapters’ are not as fictitious as he had intended … and a series of text messages that Mike received before his death point to something much, much darker…

SUICIDE THURSDAY

WILL CARVER

This one’s for me.

‘Fiction reveals truths that reality obscures.’

—Jessamyn West

‘The only cure for grief is action.’

—George Henry Lewes

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

I type:

Mike is dead. From behind, it looks as though he is sitting on his living-room floor with his hands in his lap, staring into the mirror.

And maybe that is true.

His eyes are open. But Mike is definitely dead.

Two cuts. One across the top of each thigh. There’s more blood on the floor than left inside his body. And some of that blood has been mixed with Jackie’s tears. She found him like this.

And the look on his face is one of relief, and the look on hers is mourning and sorrow and all her Catholic guilt. He is gone. She is lost. I’m somewhere in between.

Suicide is a beginning for those left behind.

This was not a cry for help. This was serious and thought out and deliberate. Mike wanted to die. But a look at the scene from the front – a different angle – and his hands are not resting on his lap. They’re in his legs.

He tried to stop it.

They’re both sitting on the floor. Broken. My best friend and my girlfriend. Blood on their hands.

Too dark, maybe. Gruesome. In this situation, you don’t know what is going on, how events transpired, the reasons behind the decision to end a life. It’s easy to focus on the wrong thing, miss what’s important, what’s right in front of you.

Again:

Apparently, the triangle is the strongest shape. The three sides push against each other perfectly so that a great force is required to misshape or break the bond between them.

That’s how we work. Mike. Jackie. And Me.

How we worked.

Mike cut his legs open and bled out on his newly polished floor. Whatever he was secretly feeling, it warped our triangle and made us weak. Our compassion must not have been equal to his self-loathing. Our love was not enough to cancel out his despair. Understanding is often outweighed by self-interest, benevolence by guilt.

Now all that is left is a line. A faint line between myself and my girlfriend, Jackie. A continuum, where one end is her and one end is me.

One side is fact and the other is fiction.

And somewhere in the middle is the truth.

Too bleak. Nobody wants to read about decaying social values and humankind’s growing disconnection with one another. It’s abstract. Obscuring what the story is really about.

In my mind, it plays out like a film.

Once more:

INT. MIKE’S FLAT – NIGHT

(Mike is sitting on the floor, opposite a mirror, in a puddle of his own blood. Jackie cries opposite him.)

ELI (V.O.)

Someone once said, ‘Things turn out best for people who make the best of the way that things turn out.’ I got a phone call a moment ago telling me that my best friend has just killed himself and, in a way, it has filled me with hope.

Maybe one day I will be able to put an end to something.

CUT TO BLACK.

WEEK ONE

MONDAY

(THREE DAYS BEFORE SUICIDE THURSDAY)

118, 117, 116…

It’s far too quiet in the office on Monday, which gives me more time with my own thoughts than is healthy.

I need a distraction: the radio perhaps, or kids screaming in the streets, or maybe even some actual work to do – anything, just to prevent my own nauseating voice from whizzing around inside my head, splitting and overlapping and altering into a maddening crescendo in the key of G, which resonates through my very being like the antithesis of orgasm. But I’m thankful: it’s nearly the end of the day now.

94, 93, 92…

With my hands poised, middle finger of my left hand on Ctrl, index finger on Alt, I count down the seconds of my last two to three minutes at work, the index finger of my right hand hovering trigger-happily over the Delete button, ready to log off.

It’s been yet another gut-wrenching, soul-destroying, waste-of-time day in which I feel as though I have offered the world nothing and achieved even less.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not depressed. It’s not depression, it’s not frustration either; it’s not even annoyance. It’s an amalgamation of all these sentiments playing off each other like some kind of sick, satanic, symbiotic mess of emotion. I get annoyed because I don’t believe in depression; thus, I get frustrated with myself. The fact that I am constantly frustrated, well, that is just depressing.

Fruproyance. That’s my word for it, the neologism that best expresses my combination of frustration, depression and annoyance. As you can see, I have kept depression’s involvement to a minimum but that is probably a result of something my therapist would call ‘fruproyance anxiety’. Of course I’m anxious; it’s a relatively unknown condition.

It’s not that I want to bring down the mood of those around me, but how can I help it? It’s come to the point where stagnation is seen as a compliment. At least my mind is still active, even if my enthusiasm is on life support. I’m constantly thinking of new ideas, of sex with Jackie, of Mum’s cooking, of Nick Drake lyrics, of money, of getting out of work, getting out of work to go and meet Mike.

I should be thinking more about Mike but I’m not, I’m too self-involved for that. I should be spending as much time with him as possible because in three days’ time it will be Thursday; in three days, none of this will matter to me because in one, two, three days, Mike will be dead.

47, 46, 45…

So where does that put me?

Here, I suppose. 17:29 on a Monday afternoon, drowning in the monotony of another laborious day in the marketing department of DoTrue. That’s right, DoTrue, capital D, capital T. A little-known computer manufacturer that opened an office in the UK two years ago. It’s my job to publicise their presence. Can you think of a more pointless occupation?

I have a degree in English language and phonetics from King’s College. Three years slogging it out with future leaders and Nobel Prize winners to end up here trying to think of interesting ways to market a new RoHS-compliant chassis, which conforms to the latest BTX design parameters, promoting smoother air flow over the mainboard and processor. It’s not the kind of creative writing that I am pursuing.

22, 21, 20…

I can see my boss pacing.

That’s never a good sign at this time. It means that he is mulling over an inspirational end-of-day speech.

He is insipid. An infant straight out of university who landed a highly paid position of power after earning a first-class degree in ‘How to Convert People into Numbers’ combined with a course in ‘Advanced Fear and Misery in the Third Reich’.

His look reduces me to a barcode in an ever-growing population of corporate whores. But the thing that really annoys me, the thing that I hate most, is the way he tries to instil a semblance of confidence and encouragement by punctuating his lectures with the phrase, ‘Okay, now let’s do some good.’

‘…So, in conclusion, our forecasting has to be spot on as we move into Q3, when we can certainly expect a ramp in the notebook market. Okay … now let’s do some good.’ As if anything we do makes the slightest difference to the world.

9, 8, 7…

Oh shit, he’s coming out.

5, 4, 3…

‘Ring, ring, ring,’ a woman’s voice sings.

And I’m saved.

‘Ring, ring, ring.’ There it is again. Pick up the phone. Please, just pick up your bloody phone. My fingers are still poised over the keyboard but in my mind they are pressed together in prayer.

‘Riiiiiii-iiii-ii-ii-iii-iii-iiing.’ The trilling vibrato that I usually hate to hear has just prevented a further twenty to thirty minutes of a Danny Elwes harangue about teamwork and targets and forecasts and e-shots and sell-out and sell-in and price lists and percentages and on and on and ‘let’s do some good’ and on and on again and, finally, he answers his phone.

I remember the day he got the ring tone for his mobile of that fucking woman singing ring, ring fucking ring. He was so proud. He let everyone know how much it cost him. Loser. I laughed to myself thinking it probably wasn’t the first woman he had ever paid money for. But that doesn’t matter now, he is back in his office and I resume the countdown.

2, 1…

Delete.

I’m logged out, standing up, jacket on, bag in hand, walking, walking, past the boss, walking, out the door and onto the bus. The number eighteen bus which takes me sixteen minutes and drops me right outside The Scam – my local pub – which is sixty-four steps from where I live.

TEXTS

Are you there?

I haven’t heard from you all weekend.

Did you do it?

Oh, my God. You did it.

Did you do it?

Please answer me.

I’m messaging a dead man.

Fuck. You did it.

I didn’t do it.

Jesus Christ. You’re alive.

Unfortunately.

Sorry to make you worry.

I was going to do it.

What happened?

I needed to see my family.

Before I leave them.

That’s still your plan?

I have to. I know that.

I’ve seen them. They have no idea about how I feel.

I don’t even know what I’m waiting for.

You have to stop putting off and putting off.

There’s never a right time. You could do it right now.

Do it.

MONDAY

(THREE DAYS BEFORE SUICIDE THURSDAY)

The sixteen-minute bus ride isn’t the toughest commute, and the sixty-four-step journey to my front door isn’t particularly arduous, either. I suppose this minuscule portion, this fraction of my everyday life, could be considered easy; I have an easy life in this respect. I start to enjoy myself; I even gain pleasure from the routine of it.

This is where my day really begins.

Almost everyone on here can be pigeonholed as a ‘young professional’. They all look relieved to be out of the office, they all look uncomfortable in a suit or sensible blouse, and they all have a mobile phone in their hands, even though they’ve been glued to some kind of screen all day.

We just want to block out the din of the world around, separate ourselves from reality for a moment.

Nothing online is real.

Yes, it’s surprisingly peaceful on the bus.

It has always interested me why people do not talk on public transport but this bus journey is a particularly anomalous phenomenon: it is silent except for the tinny treble sound coming from the cheaper earphones, but that eventually fades into white noise. The few elderly ladies aren’t even talking. It’s too late for school kids to be on here but there is one girl in school uniform who I assume has been in a detention until now, maybe for being disruptive in class, but even she is quiet, in contemplation.

I use the tranquillity of my environment to relax, read the paper or a book; but usually I spend the time scribbling ideas into my pocket notebook; ideas that I can work on when I get home; ideas for my latest masterpiece.

I hang at the back of the bus and jump off while it is still moving, slowing down before it pulls into the stop. The world seems so loud outside. I lift my headphones from around my neck, place them over my ears and select a song. Kirsty McColl, ‘Days’. It’s the soundtrack to my life for the next sixty-four steps or so. At this moment of every weekday, I am always thankful.

I stand still for eight seconds until the first time she sings the word ‘days’. It feels like the right moment to start walking to the beat, to begin my journey.

My first smile of the week.

I walk.

Sixty-four steps doesn’t necessarily constitute a journey. Sixty-four steps. Twelve after I turn left again, which is the back of The Scam, then I hit a shop called Furry’s, which only sells vinyl records and eight-tracks, my next eight steps. A butcher’s, sixteen steps. He always waves even though we have never exchanged a word. An alley that leads to the back of the butcher’s, two steps; a newsagents, ten steps; an off-licence, twelve; and a quaint coffee shop run by two war veterans who always waffle on about conflicts that nobody has ever even heard about, but they are harmless, eight steps. Then you arrive at my house.

I noticed the place about four years ago during a time I was spending most mornings at Gaucho’s, drinking coffee and etching musings into my slowly biodegrading notebook. I was unemployed and scrounging £43 per week off the state, which barely covered my coffee bill, but I was more determined than ever to finish a novel that particular year.

The truth is, I have never managed to write anything beyond a first chapter; 733 first chapters, in actual fact. Mum had read and kept them all, every last one, boxed and stored in her attic chronologically according to time written.

Why would I ever need 733 first chapters?

It acts as a constant reminder of a key issue in my life, I suppose.

I can’t finish anything.

By the summer of that year I was no nearer to completing my novel than I was at the start. Slowly running out of options, fate intervened and took my mother, leaving me with a pile of cash, three months of sequestered living, elevated fruproyance and a level of suspended animation that would rival even the most indolent of catatonic ticks.

But the money gave me something that I didn’t have before.

Choice.

So I bought up the lease on the old place next to Gaucho’s that has been closed since the mid-seventies; a place called Pretzel Logic. It was brown and damp, and the windows had been boarded up and covered in graffiti. It was mainly the obvious ‘Ben 4 Charlie 4 Eva’ kind of graffiti, with a few call-girl flyers and cards pinned to it, plus an old poster for a band named Turquoise Indigo, who looked like a Latino Supremes tribute group; also part of an unfinished poem or song that I copied down in the hope that maybe I could complete it for the person who started it. ‘So, What Now?’ A simple title and I’m not sure why I seem to love it so much. Maybe it’s because I relate to the fragmentation of the piece. I keep it with me all the time; I even kept the wooden panel it was written on.

So this place used to be a pretzel joint thirty years ago but failed because the salty bread that makes you crave liquid for a week never really caught on over here like it did in the States. When I tore down the wood to clean the place out, it smelled like pretzels. Not old pretzels either, fresh ones. Fresh, never-before-touched, brackish loaves, delicately prepared for an ignorant British public afraid of change.

Three years I have lived here now, and it still smells like fucking pretzels.

I’ve always liked the smell of paper. You know? New books, old books. Oh, old books. That damp-page aroma. That stagnant essence of wildebeest; the pungent, animal-like stench that disperses from the sleeves as the unappreciated novel gasps for air and unleashes its dankness, causing a one-foot orb of moisture around the unknowing reader’s head. I love that. But you don’t get that here. You get pretzels, and that’s one thing that will never change.

I spend the majority of my time on the ground floor of the three-level apartment building that I almost own thanks to Mum’s untimely departure from this mortal coil. No bigger than a twelve-year-old girl’s bedroom, the space on the bottom floor acts as my office, my therapist’s office, and the ‘first chapter’ library.

All the first chapters that I have ever written are now here. On shelves, currently arranged according to their genre but that can change by the day depending on mood or my need to distract myself from actually writing a second chapter.

I had an idea. To make money doing something that I actually enjoy. Isn’t that the dream?

I would open a shop of first chapters – more of a cubby hole, in truth. By using my ability/curse as a prolific starter, I would provide an invaluable service to those who suffer from writer’s block. They could come to my shop, my business, and buy a first chapter that I had written – to get them on the right road; to motivate and inspire them.

Fundamentally, I was going to sell my ideas, my hours of factual research, my own experiences and peccadilloes; I was going to sell them, like my soul, to the Devil Herself. All I would ask is that I would be credited with the first chapter of the novel which was to remain as unchanged as possible if the author were ever to be published.

It was novel. Quirky. Maybe even innovative. There’s a possibility that I could get bogged down in the legalities if anyone ever did make something out of my ideas, and maybe that would take the fun out of it. So, for now, they act as a library. A reference. A memento of my life’s work. Until the weekends, when those eight shelves of paper are open for aspiring creatives to peruse.

A clear indication of my worthless existence to date.

I lied. It’s not really my therapist’s office. This is something else that I made up.

Fiction.

Another thing that I started.

Initially I just said that I had begun seeing a therapist to get out of something that I didn’t really want to do; but now I see my ‘therapist’ every Thursday, sometimes on a Tuesday, if I need the space. It gives me an excuse to be alone, to write without interruption. For two hours every Thursday night, nobody calls, nobody bothers me, because writing is supposed to be a solitary occupation. Writers need to be alone in order to fully immerse themselves into the world they are creating.

Sometimes I just lie on the therapist’s couch that I bought especially for the library, place a Dictaphone on my chest and let go. I get out any thoughts I have about Jackie or Mike, situations from work, stories that others have told me, I release them and use this as a stimulus to start another chapter. It’s cathartic.

It’s time alone. Just the two of us. Myself and my conscience, my counsel.

My fake therapist.

The only person I can trust.

Me.

But Mondays aren’t about therapy. So I should have time to sort something I have been putting off.

SUICIDE THURSDAY

He is sitting there.

When they find Mike, he is just … sitting there.

It doesn’t really look right.

Is there actually a right way to kill yourself?

He is sitting there, on his floor, his wooden living-room floor. Recently, he decided to take a home-study French-polishing course, and this was his first conquest, his own lounge. He was so proud. And I am glad. Glad it has had a recent spruce because it makes the job of mopping up the blood much easier: it hasn’t soaked into the wood – although it did fall between some of the cracks. It shouldn’t really do that but it was only his first attempt.

He is sitting there. Dead. But actually sitting up.

Sitting, on his newly self-polished wooden floor, leaning against his used-to-be-pea-green two-seater sofa. It used to be that colour but, over time, and through lack of care and more attention paid to the wooden floor, it has turned brown.

It isn’t a dirty brown, although it is dirty. It is the kind of brown you get when you try to make purple by mixing red and blue poster paint. Of course, this never works so you end up adding yellow ochre to brighten it, then a green to darken it again. Then you think, perhaps white will lighten it up so the brown is more detectable, but this turns it grey. So you add red and blue again, maybe cadmium yellow this time.

That is the colour of Mike’s sofa.

I don’t know how it got like that, probably some self-taught, home-study, dye-your-own-sofa-to-match-your-new-room course. Gone wrong. It was only his first attempt, though.

So, he is sitting there. Sitting up. Sitting, on his newly polished floor, leaning against his badly dyed and eroding sofa. One of those sofas your aunt had in the eighties. With the gold tassling that frames and segments each rectangular section of this monstrous furnishing.

Mike is sitting there with his hands in his legs.

Not on.

In.

In his legs.

Slitting the wrists can take far too long. I can remember him saying that he could never slit his wrists; of course, I took that to mean that he would never kill himself. Not that he would do this. Some people slit their wrists in the bath. I always thought that maybe it dulls the pain or something, but actually it still hurts. A lot. It just looks like you are in a bath full of blood. Perhaps people do it just for the imagery or drama. That would be too clichéd for Mike.

Obviously.

If you slit your legs, you enter a whole other league.

It can no longer be misconstrued as a cry for help.

You mean business.

You want to die. And you want to die quickly.

In your thigh, just above the sartorius muscle, where the skin on your leg creases before your hip, there is a pretty major artery with a sign on it saying: ‘Please do not cut here.’ Mike chose to ignore this sign.

Cutting this area will cause you to die very quickly, without the aching agony that a wrist slashing incurs. Ten seconds and you’re gone. Left leaning against your sofa, bleeding on your cowboyish attempt at French polishing a floor, your blood oozing out of you and seeping down the cracks that would not have been there if you had just paid the £250 for a professional. You are left as a dry, pathetic husk. But maybe that is the way you want to be remembered.

But wait. There is a solution. You can stop the pints of blood from dropping out of your leg. There are, in fact, two options. Putting pressure on the wound will buy you some time, but your own hands are not powerful enough. The only way to stop it, to generate the necessary amount of pressure, is for someone else to stand on the gaping gash with their full weight. You could probably get up and walk to a hospital one mile away if you had only slit your wrists.

However, if you are on your own and therefore do not have this luxury, there is something else you can do. Calling for Miss Fagan across in flat fourteen will not help: she only weighs about four stone, soaking wet. Take your hands, extend your fingers and dig them inside, deep inside the slash. This should block the bleeding. Then you can phone an ambulance with the other hand.

That is, unless you have cut both legs.

Mike had opted for this extreme method of suicide and obviously had second thoughts because his hands were lodged into his thighs up to the second knuckle of each finger.

I stare at him. Sitting there. French-polished floor; eighties sofa; hands in legs; piece of glass on each side, which he’s used to jab into the artery; hands in legs; a mirror directly in front of him so that he could watch himself die, hands in legs, hands in legs, hands in legs.

That’s all that there is in the entire room.

Well done, Mike.

Not bad, considering it was only his first attempt.

After what seems like a twelve-minute gaze, I start to smile.

Maybe he did it for me.

MONDAY

(THREE DAYS BEFORE SUICIDE THURSDAY)

I turn my key and am immediately greeted by a backdraft of pretzel aroma.

And I know that I am home.

Kirsty McColl hasn’t quite finished her serenade so I lie down on the couch listening to her; I let her finish. Because she can.

I’m jealous.

I want to start writing because I had a great idea on the bus for a comedy set in a hospice for the terminally ill, but there is something that I have to do that I have been putting off.

This Friday, it is our six-year anniversary, and I want to do something special with Jackie.

Jackie. My long-term girlfriend.

Something else I can’t finish.

At first it was fine. Not great. Just, well, fine. When I first saw her, she didn’t bowl me over with good looks: she is not good-looking. She is average. Not girl-next-door, either. More like the younger, underdeveloped sister of the girl next to the girl next door.

The girl who lives a couple of doors down.

I make the call to À la Gare. A fairly exclusive restaurant in Islington built inside three train cars. Jackie loves these kinds of quirky places that sell expensive French cuisine. Anything with à la in the name is good enough for Jackie. But then again, apparently I am good enough for Jackie, so that doesn’t say much about her taste.

The maitre d’ tells me that I am lucky, that they have just had a last-minute cancellation.

I ponder my apparent luckiness for a second.

‘Okay, well, thanks for your help.’

‘Bon. Merci. See you both on Friday.’ He sounds genuinely pleased.

‘Eight o’clock,’ I confirm.

‘Oui. Yes, eight o’clock.’

And I hang up.

This year it will be different. Last year I was so nervous that I drank a bottle of Pinot Noir and nearly asked her to move in with me. This year, I am going to do it properly.

Two beers, the starter and main course, and that’s it.

That is when I will finally do it.

Friday, the day after Suicide Thursday, I am definitely, one hundred per cent, surely and without doubt going to finally do it.

This Friday, I am going to break up with Jackie.

I am going to finish something.

Thanks, Mike. I’ll get the message.

JACKIE

It’s Monday evening, work is over and, of course, Jackie heads straight to church.

Sitting in what is essentially a partitioned-by-chicken-wire shed, opposite the horrific image of a pale, skinny, bearded Jewish man nailed to a couple of pieces of wood, Jackie waits, perspiring inside the dark oak casement of the confessional. Her priest, a man she has known since birth, perches himself behind the divide in semi-darkness, like a rape victim on an American talk show: concealing his true identity; hiding behind his veil of secrecy, of morality, of faith.

She runs through the Bible in her mind until she hits Romans 14:14:

‘Nothing is unclean in itself, only to him who thinks anything to be impure, to him it is impure.’

And so begins her torture: the guilt that can only come with a faith in something that decrees a person’s every action can be interpreted as a sin.

She’s Jackie McConnell.

It’s been twenty-eight hours since her last confession.

‘I have had impure thoughts,’ she self-deprecates.

‘Continue, Jacqueline.’ Father Farrelly says this as if he is going to understand Jackie’s problem, which isn’t even a real problem, but he is just there to judge her. That’s his job.

Judge.

Jury.

And executioner.

She continues to explain her issue, the fact that she had a dream about another man. She lies and says it is a man she has never seen before, but it was Mike she dreamed about – she will confess to this on Wednesday.

Why is she apologising for something that happened in her subconscious? How does she have control over that? If you believe in the gospels, God created us all from thin air, which begs the question, who created air, thin or thick? Allegedly, humans were created by a God who decided to also give them free will. So how is it Jackie’s fault that she had a dream? But what is the point of religion if not to make one feel perpetually guilty.

Jackie’s experience should not be seen as impure. Eli purposely brought on a thought just yesterday regarding Jackie meeting a terrifyingly brutal and untimely end. This was a conscious thought that he invoked, not God or Allah or LSD or anything else. He made it happen and, in return, it made him happy. Delighted, even. Delighted because, on most days now, he sees Jackie’s death as the only way out of their relationship.

Father Farrelly listens intently to what Jackie has to say. Tutting in his head and fondling his rosary beads, he passes the sentence because this is a tribunal at which Jackie is at once the accuser, the accused and the witness; Father Farrelly merely acts as judge. He decrees that five decades of Hail Mary’s should suffice – that’s fifty times not fifty years – each one starting with an Our Father and ending with a Gloria Patri.

Because that will make all the difference.

Jackie lights a candle before leaving the church. She starts her six-minute walk back to Holloway Road and begins her own personal Monday night regime.

TEXTS

Okay, I’m gonna do it.

What? Now?

You were right. I can’t keep overthinking it.

I can’t spend every day like this.

I don’t want to feel this way, you know?

So, tonight?

Not tonight.

You’re not making any sense.

I don’t have everything in place.

Tomorrow.

Definitely?

Definitely.

JACKIE

Arriving at her flat, she is greeted by Descartes, her cat. There used to be two of them – cats, that is – but, unfortunately, Camus lost all nine lives in one go to an elderly gentleman in a Fiat Punto. The good news for Descartes, however, is that with one solitary remaining dependent, Jackie can now afford to provide the very best in feline cuisine.

Pros and cons.

Jackie squeezes the contents of the gourmet sachet into a pink plastic bowl – it looks remarkably like the duck terrine Eli made the mistake of ordering on their five-year anniversary meal at the restaurant of some TV chef that Jackie has a crush on.

He thinks she spoils the cat and, as a result, it has become quite snobby.

That’s right. Jackie’s cat is a snob.

I think, therefore, he is.

Pouring herself a large glass of Sauvignon Blanc from an open bottle in the fridge, Jackie kicks off her shoes and heads for the Bluetooth speaker Eli bought for her when his mum died. Luckily for her, but not necessarily her neighbours, the soundtrack to The Bodyguard is still cued up on the speaker’s app. She dances around the living room with her eyes closed, sipping her wine and occasionally spilling droplets onto the laminate floor, which Descartes then samples.

He laps them up but secretly he is looking down at her because he feels that a 2004 Pinot Noir would go better with his meal, he knows it’s a perfect accompaniment to any game dish.

By the second chorus of ‘I’m Every Woman’, the first glass of wine is finished. Jackie sashays into the bathroom, puts the plug in the bath, hits the hot tap on and then pours in a muscle-relaxing bubble bath that smells of elderflower, all in time with the music and all the while singing along with Ms Houston, who is now being muffled by the splashing of water.

Jackie unbuttons her blouse two notches and sashays back to the fridge for more wine. Descartes has finished his duck terrine with a mêlée of seasonal vegetables washed down with a few drops of after-dinner wine, and feels he now deserves a nap and some valuable alone time.

After another short stint on the dance floor, shimmying in time to ‘Queen of the Night’, Jackie is marginally out of breath and sweating enough to justify her bath. She drops out of her work outfit and leaves it on the floor to get wet. Standing in front of the mirror now, in her underwear, she gives herself a miniature scrutiny. Firstly, from the front, where she examines her breasts, then a side shot, where she sucks in her stomach but not by much, and then a view from behind; she tugs a little at her waistband.

Slowly lowering into the tub, trying not to scald herself, Jackie lies back with the glass of wine still clutched in her hand, her head just peeping above the bubbles, listening to Whitney trilling on with ‘Don’t make me close one more door’, waiting to hear the faux-powerful key change so popular in modern pop music, and she thinks of Eli and what he might be doing. It’s not too dissimilar from what she is doing, except Eli’s bath is a therapist’s couch, his wine is a black coffee with two sugars, his Whitney is the jazzy muzak from the coffee shop next door, and his thoughts are not about Jackie: they are consumed with the need to get this idea down on the page without distraction. He has a title: A Home to Die In.

Of course, that doesn’t happen, Jackie has taken her mobile phone to the bathroom.

She dials Eli’s number, and a picture of some smiling numbskull who looks remarkably similar to someone he used to be flashes on her screen until he picks up.

‘Can I come over?’

He really doesn’t want her to because he has to get the idea down before he forgets it.

But still, for some unfathomable reason that can only be deciphered by his therapist, who is not even real, Eli says yes.

A HOME TO DIE IN

(WORKING TITLE)

BY ELI HAGIN

F I R S T C H A P T E R

His home was perfect. And not in that sterile, Scandinavian minimalist, dentist-waiting-room aesthetic that seems to be perpetually en vogue. There was character. Exposed brick. Shelves of books. Things. Tangible things that have been collected because they are one-of-a-kind or interesting or quirky. And it could be too much but it’s just right.

The place is living.

It’s lived in.

The DONT WALK/WALK sign outside the bathroom is genuine – complete with its lack of apostrophe. It once graced the streets of Manhattan in the 1950s and was ignored by New Yorkers every day.

The On Air light in the study was once a daily feature of a BBC radio studio.

The Godfather cinema one-sheet poster in the hallway – back when they were folded, not rolled – has some light damage from its display at the Cinematograph Theatre in Shepherd’s Bush in 1972. Some would think it would devalue the piece, but, for Anders Stirling, it was added patina that made it unique.

It was real, it had lived, and it was old.

Much like the man himself.

All of these pieces of character and history had found the perfect home. A home that Anders Stirling had crafted to reflect his passion and personality.

And now they are collecting dust.

They’re dying.

Just like Anders.

And he can’t live among his things anymore because he needs care. And his family have put him in a place where he can be cared for by strangers because they can’t take the burden themselves. And they’re hopeful. Hopeful that his time will be easy passing. That he will go quietly into the night. And they will sift through the paintings and the artefacts and statues and furniture. And they will not keep any of it because it would add too much colour to their monochrome homes and clean lines and no clutter, and nothing that sparks an ounce of joy.

The vultures are circling.

As is Mrs Silverman. Every day, she walks a circuit of the freak show that is Anders’ new home, Star Acres, his home to die in. A hundred and thirteen times, Mrs Silverman paces the carpets up and down and around. The equivalent of six miles per day. She is 103 years old. A vegetarian. And doesn’t look like she’s going anywhere soon. She is, at once, an irritation and an inspiration.

Most days, Anders thinks that it would be easier if he would just die. He’s not inspiring anybody in there, he’s too pissed off with the hand he’s been dealt. He curses God and his family and rotten luck. But he can’t let go. He won’t let this disease take him.

He wants to fight.

For his Murano glass hanging lamp in the upstairs hallway. For his nineteenth-century Winfield Portable Campaign rocking chair. For his gilt overmantel mirror. His chinoiserie planters. Regency writing desk. And the oil painting of the piano player in Bemelmans Bar at The Carlysle Hotel, New York.

Carrie saunters in to Anders and says, ‘I don’t know how women find this comfortable.’

She’s a decade older than Anders but looks younger. Her hair is full and thick, you can tell she was a beauty in her day. There seems to be a hue that covers her. Some kind of blurring. A real-life photo filter that gives an analogue warmth. Like she has stepped off the set of some seventies porn film. And that wouldn’t be a shock because she is overly sexual.

Carrie lifts her skirt as she speaks and shows Anders what she is talking about. She’s too old to be wearing a thong and she seems to have put it on the wrong way around. Anders can see how it splits her right up the middle and he knows that’s what she wanted him to see.

‘No thanks, Carrie. I already ate, this morning.’

‘Next time.’ She smiles and kicks her heel up as she exits.

He can’t be here any longer otherwise he’s going to give in.

Mrs Silverman walks past and Anders calls out to her. He’s drawn to her. He likes old things. And she’s a walking antique.

‘You mind if I join you.’

‘Only if you can keep up.’

He knows it’s a joke but Anders is worried he will be too slow. But he has to try. He has to succeed with this first step. Otherwise he will never escape in time.

It’s only a few pages but I think it sets up Anders Stirling. There’s some intrigue there. What is his plan for escape? Will he die? What is his illness? And there’s the opportunity for an eccentric ensemble cast of characters. It could be the idea that gets a second chapter.

My phone buzzes. It’s a text from Mike. There’s a back and forth for a few minutes but it’s enough to throw me off my rhythm. So, I pour myself a glass of red wine. Perhaps it will act as a creative lubricant.

I should push on with a second chapter for A Home To Die In, but something else has been floating around in my mind, and I want to get something down before I forget

I write, Bud Ellis loved the movies. And Jackie calls.

I ignore it, this time. She’ll probably call back. She never quits.

SUICIDE THURSDAY

Arriving in Mike’s block on the night of his suicide, I am petrified at what I might find when, really, I should probably feel privileged.

In flat forty-one, a Puerto Rican immigrant has fallen asleep in front of the TV, which is showing a repeat of a BBC documentary about narcolepsy. He’s warm underneath his multi-coloured blanket; it took his grandmother two years to crochet it. He’s dreaming about the brunette in flat eighteen.

The grocery assistant who lives in flat twelve has lied to two student actresses about working in casting. Now one of them is riding his dick while the other muffles his hearing with her thighs and smothers his face with her firm, shaven, not-so-delicate area. He can barely breathe but he doesn’t really care.

This man will eventually understand the irritation of constantly itching and burning genitals as a result of one night’s unprotected pleasure during which he contracted herpes. The girls know that they have it, but they don’t really care either. There’s a moral there somewhere.

Number twenty-three let their cat out for the night. It pisses against the door of flat twenty-five where a drunken Mr Thompson, who hates to be called Mr T, is dying in his sleep. His wife lies virtually comatose with a smile on her face and her eyes open. He’s still warm and no fluids have been excreted just yet. They’ve been married forever but it will be a relief for her that he’s gone.

The cat moves on, passing a seventeen-year-old girl arriving home two hours and twelve minutes late from a party at which her best friend fucked three different guys and left her on her own. She had an awful night, couldn’t get a lift home, and her dad is waiting up for her with a belt in one hand and a cigar in the other. She is about to take a beating and a burning. Her mum knows it happens but lets it continue.

Flats four and six are empty and smell like wheat. The guy in flat seven works in an office and has an early start. Mrs Fagan is having difficulty getting out of the bath in flat fourteen because she relaxed with too many glasses of Port.

And here, in number fifteen, I think I’ve got it bad because my best friend has just killed himself and a police officer is refusing to acknowledge the blatant Catholic symbolism of Jackie’s bloody hands.

I go quietly. I have nothing to hide. It was suicide.

It’s one of the best things that has ever happened to me; to my creative life. Already, I have so many new ideas.

As I’m led down the corridor, hands cuffed behind my lumbar region, I hear the screams of cigarette burns, the echo of multiple, faked, diseased orgasms; I’m hit by the smell of the recently deceased, the taste of Jackie’s perfume, and that odd sense you get when a television has been left on standby. These senses build into a swelling crescendo until I am taken outside the building into an unprecedented silence.

What a beautiful, perfect evening.

TUESDAY

(TWO DAYS BEFORE SUICIDE THURSDAY)

What the hell was I doing last night letting Jackie come over?

I feel an overwhelming need to vent but I can’t, not for at least another eight hours and forty-nine minutes. I have to wait to get out of this fucking office before I can get back home and sweat it out with my fake therapist. Still, on the bright side, I have managed to get through eleven minutes of my working day before thinking about getting out of here.

I need to talk about this. I can’t keep internalising everything, I learned that in my last session. I can’t discuss this with Mike because, although his loyalties should lie with me, recently, when it comes to Jackie, he looks at me like I’m president of the Bill Cosby appreciation society.

There’s nobody here to talk to. It’s just me. Me and Sam. Sam Jordane.

He sits opposite me. I probably see his face more than I see Jackie’s or Mike’s, although after Thursday, I’ll see Mike’s face everywhere I go.

Sam isn’t my superior, but he’s not my equal either. He’s the kind of employee who may have had a dream to do something great once but life just got in the way. Now he is stuck in a job with no prospect of progression but, because he has been here so long, he has convinced himself that what he does is actually important. And, honestly, I’m not actually sure what he does.

He does do a lot of things which make it very difficult to form a connection with him about anything that is not either strictly work-related or a topic he wants to discuss.

If I wanted to know what time our meeting will be on Wednesday, he won’t tell me it will be at nine o’clock. Oh, no. He will say: ‘O nine hundred hours.’ This, in his warped little mind, is a subtle reminder to me that he was once a soldier and actually fought in a war. He was probably a chef in the Gulf or sheep-counter in the Falklands or a road sweeper in Kosovo. He never talks about it. Apparently he’s not allowed to. So now, if I want him to stop talking to me, I just ask him how many confirmed kills he has.

We start each day the same way.

‘Sooooo.’ He elongates this until he has finished typing the last few words of his email, so I know he is busy and working. He clicks send. ‘Get up to anything good last night, then?’

Oh yes, Sam, I really wanted to knuckle down to work and get some writing done. You see, I have this great new idea for a story about crumbling social values and the blur between fantasy and reality, but instead I agreed to have my girlfriend over to distract me with sex, which I’m fairly sure we both use as a tool to forget the meaninglessness of our existence even if only for a short while.

But this isn’t what I say.

‘Oh, you know, sat in, watched a film.’ I don’t even finish before he starts telling me about his own idiosyncratic routine.

‘Well, I got home late from work again.’ Of course you did, Sam, you value your job more than your own family. ‘Alice wasn’t pleased, obviously.’

Yes, Sam, that’s right, it is obvious. Obvious to everyone but you that you deliberately use DoTrue to your advantage, leaving your poor exhausted wife, who you don’t want to be with anymore, to take care of the children that you don’t want to be around anymore. And you emotionally starve them of any love that you are incapable of providing anyway. That’s two points for predictability and a bonus point for stating the obvious.

When did I get so bitter? Something to talk to my therapist about later.

Surely he won’t continue this torture by telling me something his kids did recently, which is just annoyance with their indiscipline dressed up as a cute nostalgic yarn. A tale of woe disguised as cheery anecdote. A horror story impersonating a bedtime fable.

‘And then, to cap things off, Harry got into bed with us last night and woke us up this morning at O four hundred by pissing all over the bed.’

For God’s sake, Sam, sort your kids out, you’re a military man, for crying out loud.

I don’t really know what to say to this, so I stare vacantly at my screen, but I can’t get what I did last night out of my head. Jackie just seemed so cleansed when she arrived, and she was in such a frivolous mood it made everything so easy. I think she must have finished her Hail Marys on the Tube before she got to my place.

I have to shake off these thoughts.

I only have until close of business today – Sam would say C.O.B. – to finalise a marketing plan for a new back-to-school campaign for laptops – Sam would say B.T.S. I bore myself thinking about it and, only sixteen minutes into my working day, my fingers gravitate toward the position known as log-off.

Sam never logs off. If he did any work, he’d probably burn himself out.

My computer makes a noise that jolts me back into reality, notifying me that I have mail.

It’s from Jackie:

Hey you, thanks for last night. It was great ;-)

Miles of smiles,

Jackie xxx

THINGS I HATE ABOUT THIS

ONE: The way she calls me ‘You’. She thinks it’s cute; I think it’s patronising and fake.

TWO: When people use punctuation to make smiley faces or other equally pathetic cartoon hieroglyphics to denote the emotion of the preceding sentence. It’s a butchering of our beautiful language.

THREE: Those stupid little sayings like ‘miles of smiles’ and, oh, I don’t know, ‘pixie-dust kiss droplets’ or whatever she says. I’m thirty years old this year. Just write from Jackie, or, if you truly believe it, love Jackie.

FOUR: