7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

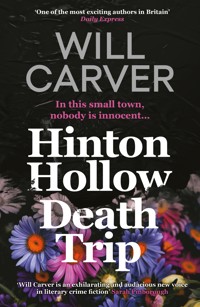

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Five days in the history of a small rural town, visited and infected by darkness, are recounted by Evil itself. A stunning high-concept thriller from the bestselling author of Good Samaritans and Nothing Important Happened Today. 'Cements Carver as one of the most exciting authors in Britain. After this, he'll have his own cult following' Daily Express 'Will Carver is an exhilarating and audacious new voice in literary crime fiction' Sarah Pinborough 'A new Will Carver novel is always something to look forward to, and this is no exception. Striking and unusual, and dark as ever' S J Watson ________________ It's a small story. A small town with small lives that you would never have heard about if none of this had happened. Hinton Hollow. Population 5,120. Little Henry Wallace was eight years old and one hundred miles from home before anyone talked to him. His mother placed him on a train with a label around his neck, asking for him to be kept safe for a week, kept away from Hinton Hollow. Because something was coming. Narrated by Evil itself, Hinton Hollow Death Trip recounts five days in the history of this small rural town, when darkness paid a visit and infected its residents. A visit that made them act in unnatural ways. Prodding at their insecurities. Nudging at their secrets and desires. Coaxing out the malevolence suppressed within them. Showing their true selves. Making them cheat. Making them steal. Making them kill. Detective Sergeant Pace had returned to his childhood home. To escape the things he had done in the city. To go back to something simple. But he was not alone. Evil had a plan. ________________ 'Gobsmacking, beyond dark, and so much fun. I would join Will Carver's cult. He's the most original writer around…' Helen FitzGerald 'A novel so dark and creepy Stephen King will be jealous he didn't think of it first' Michael Wood 'One of the most compelling and original voices in crime fiction … The whole thing feels like a shot of adrenaline' Alex North 'Twisty-turny and oh-so provocative, this is the type of book that will stick a sneaky foot out to trip you up' Liz Robinson, LoveReading 'Deliciously fresh and malevolent story-telling … a laminate-you-to-your-chair, page-whirring dive into a small British town that is turned on its head over the course of a few days. If you like something fresh and unusual, grab this book' Craig Sisterson 'It's going to take something special to top this as my book of 2020. Original, thought provoking and highly recommended' Mark Tilbury Praise for Will Carver ***Nothing Important Happened Today was longlisted for the Theakston's Old Peculier Crime Novel of the Year*** 'Weirdly page-turning' Sunday Times 'Laying bare our 21st-century weaknesses and dilemmas, Carver has created a highly original state-of-the-nation novel' Literary Review 'Arguably the most original crime novel published this year' Independent 'At once fantastical and appallingly plausible … this mesmeric novel paints a thought-provoking if depressing picture of modern life' Guardian 'This book is most memorable for its unrepentant darkness…' Telegraph 'Unlike anything else you'll read this year' Heat 'Utterly mesmerising…' Crime Monthly

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 601

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

i

It’s a small story. A small town with small lives that you would never have heard about if none of this had happened.

Hinton Hollow. Population 5,120.

Little Henry Wallace was eight years old and one hundred miles from home before anyone talked to him. His mother placed him on a train with a label around his neck, asking for him to be kept safe for a week, kept away from Hinton Hollow.

Because something was coming.

Narrated by Evil itself, Hinton Hollow Death Trip recounts five days in the history of this small rural town, when darkness paid a visit and infected its residents. A visit that made them act in unnatural ways. Prodding at their insecurities. Nudging at their secrets and desires. Coaxing out the malevolence suppressed within them. Showing their true selves.

Making them cheat. Making them steal. Making them kill.

Detective Sergeant Pace had returned to his childhood home. To escape the things he had done in the city. To go back to something simple. But he was not alone. Evil had a plan.

iii

HINTON HOLLOW DEATH TRIP

WILL CARVER

v

For nothing

vi

Choice is free but seldom easy.

—A Clockwork Orange, Anthony Burgess

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Where you will be introduced to:

A boy on a train

A detective

A pig hater

A food lover

A window breaker

and your narrator.2

3

DON’T READ THIS

You can leave now, if you want. Don’t even bother finishing this page. Forget you were ever here. There must be something else you could be doing. Get away. Go on.

This is the last time I try to save you.

Go and work out. Cook yourself something from scratch instead of ordering in. Binge on that TV show everyone is talking about. Enrol yourself in that night-school photography course. Because you will think this is strange. Then it will make you angry. Then it gets worse.

I know what you’re thinking. Who am I to tell you what to do?

Okay. Don’t listen. You weren’t, anyway.

It’s a small story. That’s what you’re getting here. A small town with small lives that you’d never have known about if you’d left when you had the chance.

Hinton Hollow.

Population 5,120.

There’s a crossroads.

You can see the park from the woods. And the school rooftop just beyond. There’s a bench in between now. Where it happened. The golden plaque screwed into the wooden seat is for the young boy. The message, from his older brother and his father.

The mother isn’t mentioned.

Of course.

It’s less than a minute to drive into the centre of Hinton Hollow but people in this town tend to walk. That will take seven minutes at a brisk pace. Ten minutes on the way back because it’s slightly uphill and you often have a bag of shopping. It takes Mrs Beaufort twice as long but she is much older. And she had that scare. With her chest. When it all happened.

The summer had seemed to stretch on for an extra month, keeping the skies light and the air warm. Parents had no need for the autumn cardigans that lined the racks at Rock-a-Buy but, still, they bought 4them. Because that is what you do in Hinton Hollow. It is the same reason there is still a bakery on the high street, though bread is much cheaper in the supermarkets of neighbouring towns, and it lasts longer. And there’s one pub that everybody goes to – The Arboreal – and Fourbears independent bookshop, which refuses to go out of business.

Hinton Hollow was safe. It was exactly the same as it had always been. A place preserved. Existing in a time that has long since passed.

Then I came. And I didn’t care about any of that.

It took five days. Small time for a small story. But long enough to touch every path and shopfront, to creep through every alleyway and caress every doorstep. To nudge almost all who lived there as I passed through.

I’m not sorry.

The more awful people become, the worse I have to be.

It’s getting harder to be me.

So, if you’re not at the gym or boiling some pasta or scrolling through Netflix, it means that you didn’t go. You didn’t take my advice. You’re still here.

And I’m still here.

That says it all, doesn’t it?

You want to know.

You want to know about Evil.

THAT THING AROUND HIS NECK

You will think she is an awful mother.

You will judge her.

Judgement has been around for as long as I have, but I find, in recent times, judgement comes quicker. And it is louder now.

Little Henry Wallace is eight years old but looks like he is six. And that boy is more than one hundred miles from home when 5somebody finally talks to him. They ask him where his mother is. But he doesn’t answer. He’s not allowed to talk to strangers.

That buys him six miles.

It’s another mile before anybody notices the thing around his neck.

The mother wasn’t always mad. Something to do with the father walking out one day. He left a note. And some unanswered questions. Quite the scandal in a place like Hinton Hollow. It changed her. People looked at her differently.

Little Henry Wallace, on the train alone, is still. He doesn’t seem frightened at all. Just doing what his mother told him. He is to sit in the carriage and not talk to anybody. Not until they ask him about that thing around his neck.

While travellers are more vigilant in current times – they are often drawn to a person of a certain age, sex and ethnicity when a backpack is left on a seat – they are not looking out for a boy, eight years of age, who only looks about six.

You may tell yourself that you would have talked to Little Henry Wallace before this point. But you, too, would have waited. It doesn’t look right, does it? That’s what stops you from approaching.

A NOTE ON BYSTANDER BEHAVIOUR

You wait because you think somebody else will help.

You hope they will.

You are scared because you don’t know the outcome.

You want to feel safe.

You are the most important person to you.

Henry has an older brother. The mother didn’t put him on a train with something around his neck. She kept him. She kept him with her in Hinton Hollow. One hundred and seven miles away.

And now there are four people around her son, on a train bound for the north of England and the elderly woman has grabbed something hanging around the boy’s neck.6

‘What’s this?’ She is not asking Little Henry Wallace or her fellow passengers, she is thinking out loud. Then, within a few seconds, she is reading out loud.

‘“My name is Henry Wallace. I am eight years old. My mother put me on this train to get me away. I can’t tell you where I came from until I have had seven sleeps. Please take care of me until then.”’

The elderly lady looks at the young boy’s face. He’s not afraid. She turns to the three passengers who have also taken an interest in the boy’s welfare.

Then she moves back to the boy and turns over the brown label in her hand that hangs on a string around Little Henry Wallace’s neck. This time, she reads in her head.

Please take care of my boy. I’m scared. Something is coming.

ONE THING TO KNOW ABOUT THE ELDERLY WOMAN

She does not stand by.

RED HORNS AND A PITCHFORK

A drunken uncle at the bottom of the bed. Aeroplanes flying into skyscrapers.

G o s s i p.

Cancer. See also: disease, politics, the Western diet.

Being nailed to a cross. Guilt. Animals in cages.

Children in cages.

A naked nine-year-old Vietnamese girl, screaming in agony, running from her village after it is incinerated in a napalm attack.

Lies.

H o n e s t y.

Some other ways that Evil may present itself:

Propaganda. Television talent shows. Telling another person who they can and cannot love. The school caretaker who informs the news 7there’s a glimmer of hope about finding the missing girls that he knows he dumped in a ditch four days ago.

Harold Shipman. Racism. The dairy industry.

Nine people with ropes around their necks jumping off Chelsea Bridge.

B l a c k f l a m e s.

I LIKE IT THERE

I have bigger stories. Of course. You think of wars and famine and plagues, I was there. If you believe in Jesus then you believe I was at his crucifixion. But I am not Hitler. I am not influenza. I am not Judas. I may appear to some with red horns but I am not Him.

I do not hold the knife and I do not pull the trigger.

People do that.

My job is to caress and coax and encourage. But I am not Harold Shipman or pancreatic cancer. I do not administer the lethal dose of morphine and I do not press the button that releases the napalm.

It is people that do that.

I am not Death, with his skeletal face and robe and scythe, and his tap on the shoulder.

I am Evil.

I am the killer-clown nightmare. I am the deviant sexual thought. I am your lack of motivation, your disintegrating willpower. I am one-more-drink, one-more-bite, one-more-time. I do not stab. I do not rape. I do not pour the next gin. But I am there.

Are you still here?

This is difficult to explain with the big stories. That is why I have chosen one of the smaller ones. That’s why I chose Detective Sergeant Pace.

I had been with him, watching him. Gently manoeuvring him into place. He was not inherently evil, that is rarer than you think. But, 8like cancer, all of you have the ability to develop into something darker and more cynical. I can bring that out in you.

I brought it out in him.

With every case, I chipped away, making him question his own involvement with each event. He blamed himself more and more with every subsequent victim he could not save. Then I appeared to him. Burning across his walls and over his ceiling. I trapped him in his paranoia and danced black flames around his life until he snapped.

I didn’t fuck the wife of a serial killer. I did not handcuff somebody to a tree and leave them to die. No. Because only people can do that.

Detective Sergeant Pace left. He packed one small case and took the first train home. Home to Hinton Hollow.

And I went with him.

I like it there.

This was my second trip.

DON’T HATE THE MOTHER

Maybe her tea leaves fell in a certain way.

Or she drew the Ten of Wands in the future position in her spread – this can indicate that you are about to experience the very worst of something, you must prepare for sudden change and disruption. Or The Moon card, which can represent uncertainty and emotional vulnerability. Maybe even The Hermit. An innocuous-looking image, but can be interpreted as a harbinger of future strife and turmoil.

Or her crystal ball turned black.

Perhaps she lit a candle and somebody who had been dead for years spoke to her but only managed to reveal the first letter of their surname. Like that’s a thing.

It’s easy to be sceptical about all that medium crap but that armchair fortune-teller got one of her kids away fast. Too fast. She 9tied a label around the boy’s neck and ditched him on a train before I even arrived in town.

The Wallace woman couldn’t say for sure that it was me who was coming but she had faith in her tea leaves or Tarot cards or rune stones or whatever she used.

One of the worst things I see in people now is how easily they believe in something. Anything.

Little Henry Wallace escaped me. One boy. Gone.

One boy. Safe.

Hinton Hollow.

Population 5,119.

More than enough to infect. To test. To darken. Dampen. Devour.

So, don’t hate the mother. She wasn’t choosing between her children. She didn’t pick her favourite to stay with her. She didn’t give one away. She got in there before me. She made a decision that day so she would not have to make a choice once I arrived.

She picked them both.

She saved them both.

The locals think she is mad. Mad for the way she dresses. Mad for the way she wears her hair. Mad for the way that she talks to her children, kisses them goodbye, for the food that she buys and the hunched way that she walks. Her spirit makes them uncomfortable.

And they will think she is mad because she put her youngest son on a train by himself and told him not to talk to anybody or say where he is from until a week has passed.

I see her. I watch her.

SOME THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT THE MOTHER

She is not mad.

She is good.

Better than them. Better than you, even.

I like her.

10As long as the rest of the town behaves as I expect they will, there will be no need to taint the Wallaces.

THREE THINGS

Little Henry was one hundred and seven miles away when I arrived for my first sweep of the old town. I just wanted to get things moving before Detective Sergeant Pace arrived. Nothing fancy. A couple of disturbances, perhaps. To get the ball rolling.

It’s not quite as simple as finding someone and making them evil. That is not how it works. I can’t just pick a person and turn them into a killer or a fraudster or have them create Facebook. I have to massage what is already within them.

Sometimes I get adultery or shoplifting or cheating on a school test.

On that first breeze through the town I got three things:

– Some salted pork

– An angina attack

– A broken window

SALTED/ASSAULTED

This was an easy one. Just to get going.

Lazy, old Evil.

You can’t be around so much death, all the time, every day, and not have it affect you in a negative way. A way that makes you act out of character. A way that shows you have become so desensitised by what you see, things you once may have found disturbing are now your normality. You may even take some pleasure in those terrible things you do in order to afford your rent.

Darren merely needed a poke towards evil.

I don’t care that Darren left school at sixteen with limited 11qualifications. He wasn’t a smart kid. He wasn’t even average. He wasn’t naughty or disruptive. He tried hard enough and he did as well as he could. He can read. He can write. He doesn’t know how to calculate the circumference of a circle but, like almost everybody, he has no real need for that information. He works in an abattoir.

That’s what I care about.

Slaughterhouses employ people of a certain psychological make-up, background and level of education. There is a high staff turnover. And a high rate of employee suicide.

It was almost cruel of me to pick Darren out.

His workmates driving the truck opened the doors and the pigs started to run out into the open. Some were clearly excited at having some space; they jumped and bucked. Some fell over and couldn’t get back up. Others were injured inside the truck, while many were coaxed out with a whip on the snout or an electric rod in the anus.

This part is nothing to do with me.

This is what people do.

Darren’s job is to round them inside where they are stunned, slit open and dipped into boiling liquid to soften their skin and remove any hair. He has worked there long enough that the sound of the animals squealing and crying doesn’t even bother him any more. He can’t even remember when it last had.

One of the pigs was acting like it knew where it was heading. It refused to leave the truck. It was whipped and probed and shocked. It ran around the courtyard, avoiding the doors that would lead to its death.

I blew past Darren. A split second. An inaudible whisper in his uncultured ear. And the thing inside him burst out.

He kicked the animal towards the door. He shouted at it and punched it in the face. Then kicked it again. He dragged it inside and grabbed a handful of salt, which he pushed into the cuts of the pig’s snout. It screamed. Darren couldn’t hear. He was already grabbing another handful of salt to shove into the animal’s anus.12

TWO THINGS YOU DON’T WANT TO KNOW

This is not uncommon.

This is people.

He stunned the pig but did not slit it open. The conveyor dragged it to be dipped in the boiling water while it was still alive.

Only the other workers saw it. And they don’t care. They’ve done the same. They’ve done worse. It is not on the village’s radar. That’s not what this visit is about.

Darren’s actions will sink in over the next two days.

Darren is changed.

ATTACK/REWARD

There are only fifteen steps, it should not have been that challenging. And she probably deserved some kind of let-up for walking to the shops rather than driving there. Instead, wheezing-through-her-fifties Dorothy Reilly had me circling above her and sprinkling her with a taste of trouble.

That determination she had to be more physically active began to dissipate after six steps. I can do that. As I said, I can increase your apathy. She could feel her chest tightening, like somebody was standing on it.

The final nine steps seemed to stretch off into the distance, but Dorothy eating-her-way-to-heart-failure Reilly still had enough gumption to lift those weary and heavy legs, one at a time, as she plodded towards the summit. And she only stopped once more with three steps to go.

Three.

Two.

One.

She probably could have done with some respite for her efforts. 13She was trying, at least. This had gone on long enough. Eating wasn’t bringing her mother back to life, it wasn’t tearing Bobby away from his new girlfriend and it certainly did not make her feel less alone. She was trying to change, make an effort.

Instead, she had me behind her, pulling at the elastic waist of her trousers as she tried to propel her weight forward.

Then she threw up at the top. Into the plant pot next to her front door. A neighbour’s light flickered on and she rummaged quickly for her keys to avoid any kind of confrontation or concern. She pushed through the door, shut it behind her and leant against it. I was just outside, listening as she tried to draw in air with those short, sharp breaths.

She dropped both shopping bags onto the floor then collapsed to her knees. The stabbing in her abdomen forced her to hunch over. She thought it was because she had just been sick, because she felt exhausted from climbing the stairs to her flat.

It wasn’t. It was because of me.

Me. And the fact that her coronary arteries were narrowed by fatty deposits as a consequence of her diet and lifestyle.

A NOTE

10,000 steps a day is not a target.

It is your minimum requirement.

This had happened to her before. Not the sickness or the abdominal pain, but the chest constriction. It usually lasted for a few minutes. She just had to find a way to calm herself down. Dealing with a symptom rather than the cause.

She sat with her back against the wall and tried to slow her racing mind. I sat with her. Her breaths grew longer and deeper, and the pain eventually evaporated.

Dorothy Reilly, sick on her breath, was thankful for the let-up, the let-off, and decided that she had earned a reward. With her back still pressed against her hallway wall, she reached her left hand 14towards one of the shopping bags and pulled out a bar of chocolate. She ate it and felt happiness for about six seconds.

Just one more…

I knew that a slightly heavier push from me could have more impact the next time I saw her.

SMASHED/BROKEN

Three minor misdemeanours seemed an adequate start. You can’t always tell where that first touch of evil will lead a person. There are people who remain unaffected. There is something inside them that can be worked with but the good in them far outweighs the possibility of any corruption. I find this less and less. Everything moves so fast now that the general population are easy to manipulate because they’re so confused by trying to keep up.

Annie Harding was at home, drinking red wine, flicking through a decorating magazine while her husband drank the other half of the bottle and zoned out to the television. Their daughter was upstairs asleep. I could have given her a nightmare but I didn’t.

I sat downstairs with the Hardings for a while and watched their odd lack of interaction. The house was neat. Too neat. The furniture had mostly been upcycled with a Paris Grey chalk paint and was accessorised with a vengeance. Everywhere, a splash of colour. Each fleck, some faux personality.

Ordered.

Too ordered.

Perfect.

But too perfect.

And the room was too quiet.

So I waved a hand over both of them and waited to see what would happen. Not enough that one might kill the other or that anything would get heated enough to awaken their child. A prod. A nudge. That’s all it took.15

The worst I could do that night was to make them talk. Make Annie ask her husband some questions about working late and what he’s been doing and where he’s been going and who he’s been talking to. I had squeezed her insecurities and let her run with it.

Suspicion is fun to play with.

The discussion was pointed but not heated. Annie was calm.

Too calm.

I couldn’t tell where it was going to go, if anywhere at all.

Then she laid down her magazine, swigged the last mouthful of her wine, stood up, went to the front door, put on her shoes, grabbed the car keys and a large rock from the front garden and drove off.

Her husband had to stay at the house because he couldn’t leave the child. But I followed her. I did not feel I had done enough for her to leave her family.

Annie Harding drove her car into the centre of Hinton Hollow that night, she waited at the traffic lights on the crossroads though no cars seemed to be travelling through in any direction, and she pulled over at the florist, exited the car and threw that giant rock straight through the glass front.

This would be the first window that she would break.

HOME

‘How old are you, Henry?’

‘I’m sorry but I don’t know you, and I’m not supposed to talk to strangers.’

‘Did your mummy tell you that? Is she the one who put you on the train?’

The kid was not scared at all. Four grown adults around him, over a hundred miles from home and he refused to disobey his mother’s instructions. The old woman was not threatening but she was becoming increasingly frustrated by the boy’s lack of cooperation.

‘Henry,’ – she kept using his name because she thought it would 16present a veneer of familiarity – ‘I’m going to have to call the police because we don’t know where you live and we need to know how to get you back. Do you have a train ticket?’ Then, aside, she says, ‘Why has nobody checked our tickets?’ The three men shrug.

I could interject, get the old lady angry, start an argument somewhere else on the carriage to put some fear in that kid with a label around his neck but, sometimes, I watch. To see if things really are worse than ever. Part of me has to respect Henry’s mother. What she did was crazy but I’m intrigued to know how it might turn out.

The elderly woman was good as her word. She borrowed a mobile phone from the man opposite and spoke discreetly to the police, explaining what had happened.

‘Okay, Henry, the police are on their way. They are going to meet us when the train stops again. Are you hungry? Do you need a drink? It’s about ten more minutes away.’

He shook his head but I knew that he wanted both food and drink.

THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT LITTLE HENRY WALLACE

He is polite.

He is brave.

He does what his mother tells him.

He is so good that I have nothing to work with.

They sat in silence until the train hissed to a stop. The man opposite Henry Wallace kept his head down the entire way so as not to make eye contact with the eight-year-old, who looked only straight ahead.

‘Okay, Henry, the police will be waiting on the platform.’

He shook his head at the kind, old lady.

‘Come on, boy, up you get, we’re only trying to help,’ the man with the phone chipped in. Henry scowled at him.

The woman put her hand out as though to hold off the man. She sat 17back down and told them all to leave and that she would stay with the boy until police came aboard. I waited with them as people got up and moved on with their journeys. I watched her. She wanted to put a hand on the child’s knee, to reassure him. She stuttered and thought better of it. It was the right decision.

I didn’t like the way the man with the phone had become so angry so quickly. The boy was so fearless. I made a note to visit that man again. From the look of the blood vessels in his cheeks, it would not be too difficult for me to push him into one more drink, one more time.

When the police arrived I left them to it and went back to find Detective Sergeant Pace burning something in his fireplace and packing his bags for home.

HOW’S ANNIE?

How did I appear to you in those first three stories? Was I a pig’s scream or a bloodied anus? Or was I Darren? Was Darren evil? I think, if I had not shown up, he would have treated an animal in that way at some point, anyway. I was a catalyst. Selfish, really, but this is my project.

I need a win.

What about Dorothy? To her I am breathlessness. To Dorothy, I am Type 2 Diabetes. I’m a punch in the gut and a weight on her chest. I hardly did anything to sixty-percent-body-fat Dorothy. If I pushed her too hard, we would be talking about a death on my preliminary sweep of Hinton Hollow. And that is not the plan.

Detective Sergeant Pace would not travel home to that.

And how’s Annie? What do you think Evil looks like to her? How does it appear to Annie Harding? Is it an image of her husband bending the local florist over their marital bed? You think she sees this reflected in the shop window, and that’s why she has to break the glass? I left before she was arrested. Before she was questioned and could come to no reasonable explanation for her actions.18

Before the town began to talk.

G o s s i p.

I am not murder or adultery or stealing. I do not dishonour your father or your mother. I do not covet your neighbour’s house, wife, slaves or animals. I am not a Lord’s name, taken in vain. This is a list of the things that people do.

I am not people.

I am not a person.

I’m trying to explain what I am, what Evil is. Is it making you angry yet? Because, from here, things get horrible. I really get to work, go to town – so to speak. So you can turn back now and there will be no hard feelings. I know that I said it was your last chance before, but this really is it. I mean it.

Once we hit day one, you will see the evil in this world.

People die and they cheat and they kill and they steal and they break windows and they cut themselves and they lie to one another and they keep secrets and they make bad decisions and they disappear. And I move around bringing these things about. I appear as an impossible choice and a shadow and heart failure and a cloaked demon and the darkness of the woods. I can make people act in a way that does not seem like themselves, but there is no acting, the behaviour is always in there somewhere.

I don’t want to ruin it. But the guy doesn’t always get the girl. The sick do not always heal. Order is not always regained after chaos.

This is it.

Last chance to turn back.

Take a minute to think about it.

THAT WAS NOT A MINUTE

Still here?

Well, here it is.

Welcome. I am Evil.19

And this is the small story of how I took five days to destroy Detective Sergeant Pace and the town of Hinton Hollow.

The town would recover.

The detective would not.

DAY ONE

Where you will encounter:

Childhood sweethearts

A town elder (or two)

Our detective’s girlfriend

The Brady family

and an Ordinary Man.22

23

THINGS ARE BLEAK

You may think that the events that took place in Hinton Hollow over those five days were awful. Too much, maybe. Unnecessary, even. The problem is that to be good is now too easy.

Because average is now good.

It used to be that you had to be Mother Teresa to be seen as virtuous. Now, another driver letting you pull out in front of them when they could have sped right past, is seen as altruistic. Benevolent. It can make your day.

The bar has been set to its lowest level.

The behaviour that was once expected is now revered. Manners and politeness and giving your time/energy/support, these simple ideals are seen as going beyond the call of duty.

You call your parents on the phone once a month, they are so pleased that you remain in contact with them. You offer a friend a lift to the airport and they don’t know how to accept your offer because it is far too generous.

Average is now g o o d.

And that makes doing something good, easy.

Which makes being Evil difficult.

And that’s who I’m supposed to be.

Things are bleak out there. You probably think that’s what I want from the world. But, you see, with everyone so depressed and downtrodden and disconnected and disassociated, the world is an evil place. It means that I have no choice but to be worse, if only to balance things out.

INCIDENTS AND ACCIDENTS

Let’s jump straight in.

There are many people to be introduced and each of them have their own part to play in the downfall of the town, but the thing people remember from that first day is that a kid died.24

The incident with Jacob Brady is the part that stands out in this dark week of Hinton Hollow history. That’s what they still don’t talk about. There’s the bench and the brass plaque and the flowers and the anniversaries and the missed birthdays.

The problem is that nobody else was there.

The two Brady boys, Michael and Jacob.

Their mother, Faith.

And the man with the gun. The Ordinary Man.

They’re the only ones who can piece the parts of the incident together. They saw the same scene, the same events, from different angles, from different perspectives. They had different lives and different histories – some of them not particularly long. But I was there, too. I had to be.

I saw everything. The darkness, the innocence, the decision.

SOMETHING I HAVE LEARNED FROM HUMANS

Your entire life can change in a moment.

Let me show you how they each saw it and you can piece things together yourself.

Once you have heard from each of them, I’ll have something to tell you.

THAT DAY IN THE PARK: MICHAEL BRADY

Faith Brady stuffed the trainer into Michael’s backpack and they finally left the school grounds. Nobody else was around. She carried both boys’ bags in her right hand to begin with. Jacob held her left hand while Michael walked slightly ahead, his heels scuffing against the concrete of the school playground.

‘Pick your feet up, Michael, come on,’ his mother instructed. She wasn’t telling him off, he knew that. He did as she said.25

‘Can we go in the park on the way home, please?’ asked Michael.

‘We’re already running late because we had to look for your shoe.’

That was not an answer.

Michael looked at his younger brother, who took his cue.

‘Oh, please, Mummy. Just for a bit.’

Faith Brady looked down at the five-year-old boy by her side, then at the seven-year-old a few feet ahead of her, and she smiled. Michael smiled back. She knew what they were doing. Ganging up on her. Running a routine to get what they wanted. She thought it was funny. Cute, even. Brothers should stick together like that. She let it go.

‘Sure.’ She rolled her eyes comically as though she had no choice. ‘But just for a bit, okay?’

‘Okay,’ they responded, in stereo.

Michael didn’t look back but he was smiling.

Jacob let go of his mother’s hand and ran forward to catch up with his brother. His hero. Michael ruffled the back of his brother’s hair when he arrived at his side, congratulating him on a job well done.

After exiting the school grounds they had a road to cross but it was residential and the flow of traffic was light at the most, particularly after the school had emptied.

‘Hold hands and wait,’ Faith called to her boys from behind.

The two boys did as they were told. They held hands and stopped at the edge of the pavement, looking both ways until their mother reached them and tapped their backs to signify that it was safe to cross.

Once on the other side, the boys released their grip and sprinted to the wooden fence on the outskirts of the park.

‘Not too far ahead, boys. Wait for me.’ Their mother was still smiling. Her sons didn’t always get on, that’s normal, but she loved their bond, and Michael was a real help with Jacob on those days when everything seemed too much.

‘Maybe we should ask if we can go in the woods,’ Jacob suggested in a hushed voice. Smirking. Scheming.26

‘What about the monster?’

‘What?’

‘You don’t know about the woods monster? Maybe you’re too young,’ Michael teased.

‘Ha ha, Michael. There’s nothing in the woods. Nice try.’ Jacob looked over at the trees and didn’t know whether he believed himself or his brother.

‘Ask Mum,’ said Michael, then he ran off further down the path.

Jacob stared at the woods for a moment and told himself that there definitely was no monster.

Michael stopped suddenly on the stony pathway and crouched down to see something on the ground more closely. A large black beetle lying on its back, its legs in the air, motionless.

‘Jacob, come and look at this,’ he shouted.

His little brother came bounding towards him with all the enthusiasm of a puppy.

‘Ah, Michael, that’s cool. It’s massive.’

‘I know. Touch it.’

‘No way.’

‘I’ve already touched it,’ he lied.

Jacob squatted down next to the beetle and pointed a finger at it. Edging it slowly closer so that he could prod it with his fingertip.

Just a little closer. Go on…

Michael was ready to scare his brother. Prepared to make a sudden movement or noise as he got a few millimetres from touching the dead bug. He did this kind of thing to him all the time. He was smiling.

‘Michael,’ his mother called out in a shriller-than-usual voice.

Mum, you’ve ruined it now, Michael huffed.

He turned around to see what she wanted. Jacob turned around a fraction after his older brother.

There was a loud noise and Michael heard a thump before his brother’s legs seem to lose all strength and give way beneath him. A man in a long dark coat was running towards the woods. His mother 27was screaming, the most deathly, terrifying howl he had ever heard. She was running towards her youngest son, then dropping to her knees and scooping him into her arms.

The man with the gun reached the line of trees in the distance and looked back over his shoulder. Michael’s mother did not notice; she was too busy rocking Jacob and holding her hand to his chest.

Michael saw. In shock, he sat down calmly on the grass a few metres from his wailing mother and bleeding brother. He didn’t say anything. His eyes were open but he wasn’t really looking at anything. Not in the real world.

He was in shock. Yes. But he had deliberately withdrawn inside himself. There was only one thing in his mind to focus on now. And that was the face of the man who had killed his little brother and would rip his family in half.

SURFACE TOWNS

I’ve witnessed many deaths.

Have you ever noticed that it always seems to be the funerals that bring people together? Feuds can be put on hold for the duration of a ceremony, grudges can be forgotten while a body is lowered into the ground. It’s the weddings that cause all the trouble. The pressure of perfection. That burden just isn’t present at an occasion where the guest of honour is decomposing in a box.

It is death that unifies people.

Almost everybody in Hinton Hollow thought it started in the park with the Brady kid, that he was the first victim of that dark week in their town’s history. Initial insights suggested an outsider, a freak occurrence, some maniac passing through their sheltered idyll. Perhaps a tearaway from a neighbouring village. There always seemed to be a little more noise coming from Roylake. Perhaps a disgruntled resident of Twaincroft Hill, a marginally more affluent village to the east that boasts luxury riverside homes but a high street in decline, 28overrun with estate agents. Isn’t it always one of those surface towns where nobody is a suspect and everyone should be?

They were wrong.

This didn’t begin with the death of young Jacob Brady. And Detective Sergeant Pace was not an outsider; he was born here. His GP was Dr Green, like so many of the folk that still live in Hinton Hollow, the ones that stayed while that young overachiever was tempted by the pulsating thrum of city life. Pace was a stranger, sure, but he belonged.

It didn’t begin with him, either. It opened, as is so often the case, with love and that most formal and public declaration of commitment. The entire village was invited and all were involved with the proceedings in some manner. From the florist arranging gerberas, to the bakery stacking tiers of sponge, to the mediocre local cover band who refused to improve with rehearsal.

But Oscar Tambor went missing, and for two days, nobody took his fiancé seriously. Because a five-year-old boy was killed that day and that case dominated. That is what clawed at the members of the Hinton Hollow community. That is what dampened spirits and wrung hearts. It wasn’t Liv Dunham pestering the police about her absent husband-to-be. They didn’t believe that Oz Tambor would simply walk out on Liv this close to the big day. But it seemed even less likely that he would have been taken.

It’s the weddings that tear people apart.

NOT THAT KIND OF PLACE

He romanticised London inordinately, despite the necessity to escape. That is one of the reasons he sat facing backwards on the train. He wanted one last look, to hold it in his view for as long he could, drinking in the place he had loved before everything turned to shit.

Detective Sergeant Pace was apprehensive about returning to 29Hinton Hollow. It had been years and, though he knew the village and its people would not have changed significantly since the date of his departure – it’s not that kind of place – he understood that he was never getting back to being the person he had once been; the person they all thought they knew.

The train journey seemed to end too near the point at which it had begun. They were less than an hour from London, and Hinton Hollow was the next stop. It wasn’t even necessary to change lines at any point. Hinton Hollow has a quaint but historic station on a route between two major cities. Pace wondered whether it would have made a difference to his life if he’d simply commuted. He could have worked in the city that had attracted him in the first instance but had an escape at the end of the day. The security of his hometown.

He still would have seen those people jump from Tower Bridge, though. And no amount of freshly baked bread or civic conviviality would have been able to make him forget.

The woman opposite him had distractingly smooth legs. City legs, he thought to himself. Nobody in Hinton Hollow could possibly have legs like that. Her hair was straight, mousy, stroking lovingly at her thin shoulders. Her gaze was fixed on the pages of her book as Pace’s was on her calves. It was a novel he’d never read but instantly dismissed as some unrealistic crime story. He breathed in that reality and it was nothing like the books or movies portrayed.

Pace flicked his eyes up but the woman was still engrossed in her fiction. She was either reading slowly or pretending to read because she hadn’t turned the page in the last ninety seconds. He noted that.

I was next to her. Gently caressing her interest so that she would play with him, tease him.

Pace looked out of the window to his left; the buildings had been getting smaller the further he journeyed from London. Even the large telecom company buildings surrounding the last train stop seemed humble in comparison to the adopted home he was running from. He had reached the part of the journey where the concrete gave way to the crops and waterways that led to Hinton Hollow.30

He imagined the playful fake reader opposite him was commuting to the city at the other end of the line, and for a moment he thought that she was lucky.

Facing the capital also served the advantage that he could watch where he was coming from. He’d notice if someone or something was following him. He could keep an eye on his own shadow; looking out for the darkness. He had no idea I was right there with him.

The carriage gently urged his travel companion’s chest forward as the train began to slow for his stop, Pace took the opportunity for one final innocent dalliance with the sultry pretend bookworm. He wasn’t going to see legs like that for a long time. And he wouldn’t get a smile like that from a stranger in Hinton Hollow. Because nobody was a stranger.

I put a hand on her back and she produced a coquettish little smile, a knowing look. And Pace put his hand on his right trouser pocket to check for his phone. He’d have to speak to Maeve at some point and some point soon. She’d be wondering where he was. He knew how she would react to him leaving so suddenly. They’d woken up together the previous morning.

Detective Sergeant Pace could have his back turned to his hometown all he wanted. And he could tell himself that it was for his own protection – that he was preserving the people he had known and edged uncomfortably away from. But all it meant was that he couldn’t see what was coming.

HEADING OUT

I was all over town. Everywhere. If you are still here, listening to my story, you will also be everywhere.

Try to keep up.

Liv had been talking to Oz Tambor about Maggie when Detective Sergeant Pace’s train pulled in to platform two: there are only two 31platforms at Hinton Hollow train station, one heading to London, the other to Oxford. Maggie was the daughter of the flower arranger who had prepared the wreath for Oz’s father’s grave four years previous and had woken up that morning to a broken shop window.

‘She’s certainly got her mother’s eye,’ Oz had proclaimed, feigning enthusiasm for the subject once again.

He wanted to marry Liv Dunham. He loved her. He had loved her for years. They’d become a couple in secondary school and neither had strayed in that time. Neither had lived. It was an inevitability that this day would come. They knew it. The whole town knew it.

OTHER THINGS THE WHOLE TOWN KNEW

Oz and Liv were perfect for each other.

Their love was so true it was almost enviable.

They were stable.

They were predictable.

Oz was posturing, rattling out some line he’d picked up from Liv and her friends about the autumnal colours being reflected in the flowers and how it would be a continuation of the forest. Bringing the outside to the inside.

He said these kinds of things because he knew it made Liv happy to think that he wanted to be involved in the planning. She had her notebook and her stickers and her colour-coding; he had his nodding agreement.

What a team.

SOMETHING THE WHOLE TOWN DIDN’T KNOW

Stability can leave a person yearning.

I can work with yearning.

32Oz was aware that the series of planned moments were important to her, that the spectacle of that one day had become her drive. It was now a project. Though Oz was not hugely interested in what the ceremony looked like, it was important to him because it was important to Liv. All he wanted to do was marry the woman he had always loved.

They had agreed to take the week off work so neither would be stressed with the balance they’d have to perform in the run-up to their vows.

It hadn’t worked like that for Oz.

Everything had become about the wedding. It’s all they talked about. It was only day one and he had already started to miss the office.

‘I don’t think it’s worth worrying about now, Liv. Everything is in hand. We should just enjoy this week together.’ He bit into his toast, the crunch punctuating his sentence.

‘I know. I know. You’re right. But I’m only planning on doing this once, I don’t want to drop the ball now.’ Liv was standing waiting for the kettle to boil while Oz sat at the kitchen table. She took half a slice of his toast and started to eat it. She’d always done this, claiming she wasn’t a breakfast person; a morning coffee would suffice. It didn’t annoy Oz that she did this. It was another of her quirks that made him smile and give that every single morning shake of the head.

‘I get it.’ He swallowed his food before continuing. ‘The whole town is in on this; they won’t let anything go wrong. Nothing will go wrong.’

A conscience would have made me move on to one of the other 5,019 people left in Hinton Hollow. If, in any way, I had found them interesting, I would have danced my way around somebody else’s kitchen that morning. But this was too perfect to pass up.

The kettle clicked as though it had an idea at that moment. Liv poured the boiling water onto her two spoons of instant coffee, stirred and took it over to the table, where she sat with her relaxed husband-to-be and the gnawed triangle of toast she, apparently, didn’t even need.33

‘Surely it’s not against the rules to talk about our preward?’ She smiled. She even winked. She always winked when she said preward. Another of her quirks. Making up words. She was an English teacher at the same school she had attended as a teenager, the same school where she had first got together with Oz.

The school that Jacob Brady would never be old enough to attend.

The honeymoon was to be their reward for the hard work of organising a wedding. Their combined wage wasn’t high so they had chosen Paris and Provence. A simple trip. Liv wanted Paris due to its literary and romantic connections, then a move on to Provence would provide the quiet relaxation and seclusion expected of such an excursion.

Both places began with P. It was their reward. Hence, preward. The word usually made them both grin like idiots – small town, small things – but not on that day. Oz’s eyes simply widened and they both stopped chewing.

I found this irritating. It made Liv come across as sickly. And false.

So I danced. I danced around that kitchen and covered it in worry.

Looking back, it’s easy to say that the quarrel that followed was, perhaps, where this all began. Oz had never been abroad; he’d hardly been out of Hinton Hollow, so he’d never thought about filling in a form and sending off his birth certificate. Liv was annoyed because it was the only part of the organising that he was solely responsible for: ensuring he could leave this country and enter another.

‘I’m heading out for a bit.’

That was the last thing he said to Liv before he was taken.

Before that, he’d told her to calm down. That these things can always be resolved. He’d told her there was an office you could go to in Wales that would sort it for you on the same day. She argued that he was confused and was thinking about the process for obtaining a driving licence.

It all went nowhere and became too much.

My real work had begun.

But it hadn’t all started with this confrontation about a passport, 34as you know. Nor did it begin when he walked out of their front door.

And it would not end on day five when that sixth bullet was due to hit Oscar Tambor in the face.

THAT DAY IN THE PARK: JACOB BRADY

You can’t blame Michael. He’s just a kid. And he’ll be blaming himself forever. Sure, if he hadn’t misplaced his shoe then they all would have left school at the correct time, the Bradys would have been a part of the crowd.

So, blame the man with the gun.

Blame the mother.

Blame me.

It wasn’t Michael’s fault.

And that is not how Jacob saw it at all.

On his hands and knees, five-year-old Jacob Brady scampered around the dusty floor of the changing area, checking beneath every bench, hoping that he would be the one to save the day and find his big brother’s missing trainers. Yes, they argued sometimes and they fought about the most insignificant things and they could’ve shared a little better at times, but Jacob thought that Michael was the coolest guy in the whole world.

He never got a chance to tell him that.

They shared a bedroom. Even though there was another room upstairs in their house. Their mother thought it would be a good idea to keep that other space as a playroom. Somewhere that didn’t necessarily have to get tidied at the end of the day. Full of toys and paints and superhero costumes.

Their bedroom was smaller than the playroom. They had bunk beds. Michael got to sleep on the top bunk because he was older, but Jacob didn’t mind. His brother always hung over the edge at night to talk to him when they were supposed to be sleeping or being quiet. Jacob loved that about him.35

‘Here’s one,’ Jacob shouted, proud of himself. ‘I don’t know where the other one is yet.’

‘It’s okay. I’ve only lost one. The other one is in my bag. Well done. You saved me. I thought Mum was going to kill me.’ And he did that thing where he ruffled Jacob’s hair in a playfully patronising way to disguise his affection.

Jacob didn’t mind. He kind of liked it. He knew what it meant. That’s why he never flattened it back down.

‘Look, Mum,’ Michael said, ‘Jacob found it. Under the bench.’

Jacob was still smiling.

‘Well done, Jacob. Shall we get going now, we’ll be the very last ones out today, I think.’ His mother started towards the door and the boys followed.

Outside, they ran through a well-rehearsed skit that they used to get their mother to do what they wanted. Michael told his brother once that she couldn’t refuse politeness. Especially from Jacob.

She was a sucker for her hazel-eyed angel.

It worked. Jacob’s mother agreed that they could cut through the park and play for a bit before returning home for dinner.

‘You will eat everything on that dinner plate.’

The boys didn’t really pay attention to that last remark as they ran off down the path.

Then Michael was saying, ‘Go on. Touch it.’

And Jacob knew his brother was trying to scare him.

Go slowly.

Jacob Brady didn’t even have time to be frightened. He turned around to see why his mother was calling Michael and was assaulted by the sound of the gun firing. Before he even reached the top of his flinch, his heart had been ruined.

There was no time to spot the horror on his mother’s face and no time to turn to his big brother for help. He didn’t even get to touch the beetle.

No time for goodbyes.36

No more bad dreams to wake Michael up with in the middle of the night or ideas for new games they could play in the day.

And no opportunity to tell his big brother that he was right about the monster in the woods.

INVISIBLE SHADOW

Pace wanted so much for it to feel like home. To make his time pass more simply. He had missed Hinton Hollow in some ways and hoped he’d somehow find a place to slot back in.

He recognised all the town landmarks immediately. It’s possible to see right down into the heart of the village from the station platform. A straight line that leads to the crossroads, where life glides along, holding hands with decency. Unlike the city, where existence seems to thump around corners, scratching at weakness and temptation.

His shoulders slumped slightly but noticeably as the train pulled off, taking the attractive book woman away to Oxford. Pace thought about turning back for one last shared glance. I held her interest in that flirtation until she was out of sight before switching my focus back to the detective. I let go of her and she went back to reading.

The mobile phone vibrated in his pocket.

Maeve.

They needed to talk. He wanted to. So that he could explain his departure, so that he could explain what had happened on that last case. But not at that moment. Not right then. He’d just got back. He was Hinton Hollow. Maeve went back into his pocket and through to voicemail.

With his back to the track, an invisible shadow stretching out behind him, Pace started his walk into town. He could see RD’s Diner at the bottom of the sloping street, bustling with trade, its glass front still in one piece – for now – still displaying the dated, American diner-style signage; it offered free refills at a price any of the coffee chains would charge for half a biscotti, if you ate it outside.37

The police station was close but Pace was hoping he could avoid that for as long as possible. They were expecting him. To them, it was a temporary transfer, to Pace, it was a sabbatical. A break. An escape. He wanted to announce his own return. To spread the word himself, on his terms. The darkness I had brought to his town was moving slowly but deliberately, even downhill, but, in Hinton Hollow, word has no choice but to travel fast.

His plan was to hit RD’s place first, sample some of their legendary homemade cake and drink coffee – no refill necessary on this trip. He’d move on to the corner grocery and pick up a few essentials, give the locals a few minutes for g o s s i p. That would only leave Rock-a-Buy, across the road on the adjacent corner, where Mrs Beaufort would undoubtedly already be expecting him. Then he would go to work.

It was important to visit the old lady, because if she welcomed him back with open arms, he knew the rest of the village would fall in line.

That was Pace’s plan.

Mine was to chaperone him around. Make sure his paranoia did not flare up. Not touch him. Keep the shadow off his feet and flames from the walls. Let him meet the various pillars of his former home and remember them as they were.

Then I would change them so that they were unrecognisable even to themselves.

SAMARITAN

Maeve Beauman woke up alone.

After her husband had died, this had been a novelty. Something new to embrace, to try. But getting together with Pace had changed that. She’d convinced him to stay the night before, but he had sped out the door the next morning to work on his case. He hadn’t told her too much about it but she’d seen the news. A suicide cult with 38no leader. People getting together and jumping off bridges to their deaths.

She hadn’t asked him too many questions, she didn’t want to push. It was the same with their relationship. She liked him more than he liked her. That’s what Maeve told herself. So, the things she often wanted to say or feel, she held back.

But she needed to hear his voice.

She called. It went to voicemail.

‘Hey, it’s Maeve. I just wanted to check in with you. Make sure everything’s all right. I’m guessing you’re busy. I’ve seen the news so you must be tied up with all of that. Looks crazy, I don’t know what this world is coming to, you know? Why would someone do that? I suppose you’re more used to it than I am. Look, I just wanted to talk. You left kind of suddenly. I know you had to get to work but we had such a great night before that. We were close. It’s just hard for me. I guess I’m being overly sensitive. Felt a bit like you fucked and ran. I know that’s not it, obviously. It just would’ve been nice to have a little more of a morning together. Difficult, of course, with everything going on. I totally understand. I just … Can you just call me when you get this, please? Let me know how you’re doing. Maybe you’ll be around later? Anyway … call me back or drop me a text if you’re tied up. Speak soon.’

The message was relaxed. Maeve was not.

More feelings locked away.

It would not take a lot from me to open up the detective’s girlfriend. To make her true.