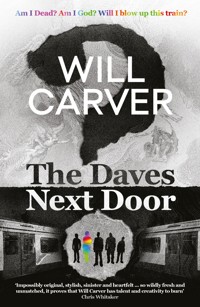

The Daves Next Door - The shocking, explosive new thriller from cult bestselling author Will Carver E-Book

Will Carver

7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

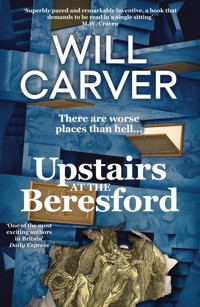

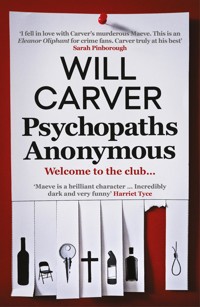

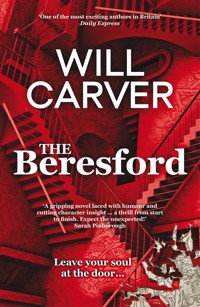

The lives of five strangers collide on a London train carriage, as they become involved in an incident that will change them all forever. A shocking, intensely emotive and wildly original new thriller from Will Carver… 'Impossibly original, stylish, sinister and heartfelt. The Daves Next Door is so wildly fresh and unmatched, and once again proves that Will Carver has talent and creativity to burn' Chris Whitaker 'Once again, Will bends and twists the genre with a novel that is astonishing, profound and hard-hitting' David Jackson 'So clever, so dark, so utterly original. Where does Will Carver get his ideas?' Victoria Selman 'Stirring. Ambitious. Irreverent. Compassionate. Completely devoid of giveable f*@ks' Dominic Nolan ________________________________ A disillusioned nurse suddenly learns how to care. An injured young sportsman wakes up find that he can see only in black and white. A desperate old widower takes too many pills and believes that two angels have arrived to usher him through purgatory. Two agoraphobic men called Dave share the symptoms of a brain tumour, and frequently waken their neighbour with their ongoing rows. Separate lives, running in parallel, destined to collide and then explode. Like the suicide bomber, riding the Circle Line, day after day, waiting for the right time to detonate, waiting for answers to his questions: Am I God? Am I dead? Will I blow up this train? Shocking, intensely emotive and wildly original, Will Carver's The Daves Next Door is an explosive existential thriller and a piercing examination of what it means to be human … or not. ________________________________ 'Will Carver is a thought-provoking and masterful writer of gut-punching fiction ... a powerhouse of a novel. Think Ira Levin at his best' Michael Wood 'Will has this uncanny knack of delving into your soul and revealing all the things you really think but are too scared to voice. Absolute GENIUS' Lisa Hall 'Another ingenious genre-bender … provocative, twisted and mind-bendingly original' Sarah Sultoon Praise for Will Carver 'One of the most exciting authors in Britain. After this, he'll have his own cult following' Daily Express 'Unlike anything you'll read this year' Heat 'Move the hell over Brett Easton Ellis and Chuck Palahniuk … Will Carver is the new lit prince of 21st-century disenfranchised, pop darkness' Stephen J. Golds 'Incredibly dark and very funny' Harriet Tyce 'I fell in love with Carver's murderous Maeve. This is an Eleanor Oliphant for crime fans. Carver truly at his best' Sarah Pinborough 'A darkly delicious page-turner' S J Watson 'One of the most compelling and original voices in crime fiction' Alex North 'Weirdly page-turning' Sunday Times 'Laying bare our 21st-century weaknesses and dilemmas, Carver has created a highly original state-of-the-nation novel' Literary Review 'Arguably the most original crime novel published this year' Independent 'This mesmeric novel paints a thought-provoking if depressing picture of modern life' Guardian 'This book is most memorable for its unrepentant darkness…' Telegraph 'Utterly mesmerising…' Crime Monthly 'Will Carver's most exciting, original, hilarious and freaky outing yet' Helen FitzGerald 'Vivid and engaging and completely unexpected' Lia Middleton

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

A disillusioned nurse suddenly learns how to care.

An injured young sportsman wakes up to find that he can see only in black and white.

A desperate old widower takes too many pills and believes that two angels have arrived to usher him through Purgatory.

Two agoraphobic men called Dave share the symptoms of a brain tumour, and frequently waken their neighbour with their ongoing rows.

Separate lives, running in parallel, destined to collide and then explode.

Like the suicide bomber, riding the Circle Line, day after day, waiting for the right time to detonate, waiting for answers to his questions: Am I God? Am I dead? Will I blow up this train?

Shocking, intensely emotive and wildly original, Will Carver’s The Daves Next Door is an explosive existential thriller and a piercing examination of what it means to be human … or not.

THE DAVES NEXT DOOR

WILL CARVER

For God’s sake

God moves in a mysterious way.’

—William Cowper

‘Hell is other people.’

—Jean-Paul Sartre

‘In an infinite multiverse, there is no such thing as fiction.’

—Scott Adsit

AUTHOR’S NOTE

This is not a book about terrorism. Nor is it about terrorists. However, through researching many real-life attacks, reading media coverage, eye-witness accounts and survivor testimonies, there are certain threads and consistencies that have been used for authenticity. The attack mentioned is purely fictitious and so absurd in its scale and intricacy as to separate it from any real-life event. Care and sensitivity have been taken but, in places, likenesses have been unavoidable and serve only the quest for realism.

The terrorism, or threat of terror, forms only the crime element of the story. It is a small aspect of what happens. This is a story about cause and effect. It is about the interconnectivity of everything and everyone on this planet. It is about compassion, understanding, listening, and asking the right questions.

The events of this book are as real as I can make them, but none of them actually happened. Though, as the book explores, perhaps, somewhere, across the universe, everything I have written as fiction, scarily, has the possibility to be fact.

INTELLIGENCE AND SECURITY COMMITTEE

35 Great Smith Street, London SW1P 3BQ

14th February 2023

Could this have been prevented?

The ISC has, today, begun an investigation to review the intelligence concerning the London attacks on 21st July 2022. The initial report into the fourteen bombings and four vehicle collisions has been set aside. Though useful for documenting the events, the scope of the report only offers a broad understanding of how the incidents unfolded on that day.

The prime minister has asked how so many of the perpetrators of this crime were unknown to British intelligence and whether prior knowledge of several of the bombers should have meant that they could have been stopped.

The Intelligence and Security Committee intends to deal only in the facts. Public opinion has been swayed by conjecture and conspiracy theories that will not be entertained by this investigation. (A separate investigation will be conducted regarding the allegations of an eighth underground bomber who did not detonate and walked away.)

Information will be derived from police logs and transcripts as well as photographic and video evidence. Those people involved will be questioned and requestioned. False articles and inaccurate reporting have resulted in needless distress for the families of those affected and the people who survived the ordeal.

In order to achieve the accuracy required, the ISC intends to examine the most minute of details over a minimum period of twelve months. The final report will be lengthy and without summary, so as not to misrepresent the facts.

The prime minister’s questions, as well as the concerns of constituents, deserve to be investigated and answered, and the ISC’s duty is to present only the facts of what actually happened on the morning of 21st July and the days leading up to it.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE?

There’s a bigger story here.

Of course there is.

There always is.

There has to be something greater than we are. God, or the universe. And there is always somebody worse off than us, too. But these larger events are the result of something smaller that occurred before. And then something even smaller than that. Something that seemed insignificant at the time, unrelated.

Then there is a knock-on effect.

An event, seemingly meaningless or trivial, sparks something more revealing, until it eventually implodes into chaos or poignant catastrophe.

When a psychopath is captured after going on a serial-killing spree, the bigger story is that of his victims and their families and the atrocities that occurred. There’s a smaller tale where a young boy whose frontal lobe did not develop the way that most do – due to bad genetics – leaves him with an incapacity to empathise or feel true remorse. As a child, he innocently dresses up one time in one of his mother’s gowns, complete with stilettos and jewellery, and her reaction is to curse and beat him for doing so. She locks him in the cupboard beneath the stairs for a couple of hours.

There’s another, smaller story which might explain the reason she reacted this way.

And, of course, something smaller before that.

In some other universe, she laughs at his playfulness, hugs him and kisses the top of his head.

When a glacier melts or the earth quakes or a tsunami hits, the bigger story is concerned with the devastation and the loss of life.

Then there are the smaller flutters that form a chain linking to the main event. Tales of greed and lies and drilling and the invention of the combustion engine and money and farming, and they don’t seem to correlate, they don’t appear to be related in any way. But they are. It all is.

Everything is.

Everybody is.

And when a carefully orchestrated attack on a capital city occurs, when seven train carriages explode, followed by four buses and the foyers of three high-rise buildings, and unmarked vans indiscriminately plough through pedestrians on four of the bridges that cross the Thames river, this is the effect of all the indiscretions and secrets and decisions made before it happened.

All the wrongdoings of government, all of the policies passed to preserve the self-interest of the few, all the political rhetoric and religious contradictions and arguments so old that nobody can remember where it all began or why they are supposed to hate each other.

All the Mental Health Weeks that seemed more like a marketing strategy than a true address of a growing problem. All the hashtags that diminish the size of the responsibility we have towards one another as human beings, seeking an identity, striving for recognition or equality.

All of these things. They are related. And they build and mutate until the only outcome is a killing spree. A volcanic eruption.

An explosion.

One café and two office blocks in the financial district.

The Central Line.

Bakerloo Line.

Hammersmith and City.

Jubilee.

Northern.

Piccadilly.

And the Circle Line.

A flash of white light, followed by chaos and terror.

Then the buses. And the bridges. And Earth feels more like Hell.

Look backwards for the causes and forward for the effects. The broader picture tells the larger story, but, to understand how every choice, every micro-decision impacts more than just ourselves, to see how linked we are, not just locally or globally, but universally, we must continue to think big while looking at the small.

One incident.

One train carriage. Edgware Road. The Circle Line. 08:51.

Thirty-two passengers.

Infinite possible outcomes.

And one bomb.

There were many vantage points on that train car. Everybody saw what happened, how it unfolded. Some saw a brainwashed kid, others saw horror. They saw a terrorist. And one may have even seen God.

All of their stories are different.

All of them happened.

And all are true.

Not one thought or prayer can make the slightest difference.

THOUGHTS (AND PRAYERS)

Our prayers are with the families of the seventeen schoolchildren gunned down by a former student at some American high school you’ve never heard of.

The prayers of our entire nation are with the people of a state or island or coastal town caught in the path of Hurricane Whoever.

Thoughts and prayers go out to all those who were fortunate enough to have known this celebrity and national treasure, who passed away last night after a long struggle with a disease that normal people die from every day.

People do this. People say this. People have the ability to affect gun regulations. People can change laws. People can run drug trials and cure illnesses.

But people pray.

They pray for guidance and forgiveness. They pray for themselves and they pray for you. Then they pray for others they have never met but are going through a hardship they are lucky enough to never experience themselves.

And maybe they think it’s enough. Maybe they think it helps.

It doesn’t mean they are stupid because they put their faith in a God. Hell, it doesn’t even mean that there is no God.

He’s just stopped listening. He’s busy. He’s given up on His experiment because the free will thing blew up in His face.

All day, every day, people are talking at Him. They want help or they’re sorry. Mostly, it’s because they don’t understand what’s happening, how things got so bad. They have questions. A million questions for one God every minute.

He can’t keep up. He can’t answer them all. He has no assistant, no secretary. No idea when things got so out of hand.

What He does have are questions of His own. Surely.

Who does God pray to?

PART ONE

THE DARK

1 THE DAVES (AND THE NEIGHBOUR)

One of the Daves says that his tongue exploded. That he had an allergic reaction to something. It swelled up in his mouth so much that it just … popped. And he ended up in hospital. That’s when they found it. The tumour on his brain.

Then he says, ‘They reckon I’ve got a twenty-five percent chance. Of living.’

Not a seventy-five percent chance of dying.

He sounds mistakenly optimistic.

But the fact that he sounds like anything other than a drunken muffle leads his neighbour to conclude that this Dave is probably lying.

This Dave stinks of white wine and piss. And surely the inside of his mouth should look like strips of week-old deli meat if something detonated in there recently.

‘Shit, Dave, that’s … What, they can’t treat it?’

What else can you say?

Sorry to hear that.

Still a chance, eh?

Show me your tongue, you damn liar.

The damn liar insists that he’s on some medication that can shrink the thing. That he has to keep going to the hospital for check-ups.

‘That’s probably why you haven’t seen too much of me over the last three or four weeks.’

It’s true. He’s been cooped up inside his flat, trying to drink himself to death. He rents. The tongueless idiot has changed the locks on the front door so the landlord can’t get in. He hasn’t paid his rent for months. Blames it on the tumour. And the tongue thing. That’s why he hasn’t been at work or whatever.

‘Yeah, I might have to stay in hospital for a bit while they do some tests. See if the thing is getting any smaller. You know?’

His mouth is disgusting. Teeth like a burnt fence. Thick, white globules of saliva forming in the corners, stretching as he spits out another of his made-up tales. The neighbour can’t stop looking at it, though. Trying to catch a glimpse of the allegedly blown-up flesh inside.

This Dave is on edge. He doesn’t like being outside the flat in case the landlord shows up. But he also has a compulsion to check his letterbox on the ground floor five times a day. No one knows what he is expecting but it must be important. Perhaps a letter from his fictitious doctor about the imaginary tumour.

‘Oh, right. You’d have to stay in there long?’ The neighbour regrets the question immediately. He just wants to leave. Now it’s a conversation.

‘I don’t know. It needs monitoring.’ The Dave stutters. Caught off-guard, he hasn’t prepared this part of the story and has to improvise. Now neither of them wants to be here.

The neighbour nods, politely.

This Dave stares at him for a few seconds then says, ‘Anyway, I just wanted to check the mail. I’m expecting a cheque.’

Damn. The neighbour is intrigued but bites his tongue. His plump, present, intact tongue.

‘Well, I’ll let you get on.’ He wonders whether he should mention the illness, say sorry or something, show some sympathy.

‘Yeah. I’m sure I’ll see you around.’ This Dave smiles, but not an open-mouth smile that would reveal anything mangled behind his decaying incisors.

The neighbour is not sure when he’ll catch another glimpse of this Dave. Maybe he does have a brain tumour. Maybe it will pop like his tongue. The only thing he knows for certain is that the Daves’ door will slam at six-thirty in the morning when he next runs downstairs to check his empty mailbox again.

2 THE OLD MAN (AND THE ANGELS)

‘Am I dead?’ the old man asks, the tingling in his right shoulder reverberating down to his fingertips, stabbing at his skin from the inside as it descends. He smiles through the pain, hoping he got it right this time.

The couple look at him then at each other, their gaze planted somewhere between welcoming and apathy.

Their necks creak back in unison towards the enquiring pensioner.

But say nothing.

At ninety-one, the old man is, indeed, old. Elderly. Aged. Senescent. Yet, beneath that crepe-paper skin and drooping brow is a man of sound mind, of memories. His birth, sandwiched between two wars, has left him resilient and unforgiving. But the old lady’s death two years ago to this very day has kept him anchored on all sides by his grief.

All he has are the memories. Snapshot recollections that no longer resemble her.

And he doesn’t want them any more.

‘Am I dead?’ the old man asks before folding over and retching his solitary heartache towards the kitchen floor, trying with all his might to keep the pills inside, so that they may do their worst to him; so that they may punish in order to end his punishment.

The couple look down on him and the dribble of bile that hangs from his thin lips, then turn to one another, their mood perched somewhere between uncertainty and true mercy.

But say nothing.

They appear like angels before him, not bathed in light but swathed in blur. The old man feels they are here to take him away, to end his substantial time in this realm. He does not mind if there is a Heaven and he is to be rejected from it as a result of his actions. He is not worried about eternal nothingness because it is the presence of somethingness that brought him to this juncture.

His chest fills with cold, and he welcomes the possibility of Hell.

It would be a relief.

‘Angels. My angels.’

Then he falls.

The old man’s legs give way beneath him as his motor skills evaporate en masse, the effects of those small white capsules – and cheap Scotch – betraying his brain. He is losing control.

His face crashes into the hard laminate, cutting below his right eye and grazing his cheek with a friction burn as his delicate skin sticks to the faux wood.

The couple do not flinch even as the old man grunts, the air in his lungs expelled unintentionally as his ribcage smacks the ground beneath, their emotions standing somewhere between anticipation and composure.

But they say nothing.

They remain in silent contemplation, looking down on the pitiful scene beneath them, the old man shaking, writhing in agony as he loses his battle to contain nausea. The woman wants to look away but cannot force herself to do so. She wishes she could offer her hand or a comforting word but something inside of her is preventing empathy.

The old man claws at her feet, desperately trying to pull himself to his knees. Their eyes meet, his show empty yearning, hers glaze with a thin saline film. Her partner watches over the old man’s appeal but does not have the inclination to reach out.

‘Am I dead?’ the old man asks one final time, his hands now clutching at the ankles of the pretty girl whose face remains pixelated, only darting into focus for short bursts.

The couple stare on, unblinking, concentrating. The old man’s breath now laboured with the occasional stab of a dry tear, and he asks them the question again. This time without moving his lips. This time his thoughts are conveyed in a look. His query is said in his head.

But they hear.

And this time they answer.

Am I dead?

‘Yes,’ says the woman, finally reaching out a cold, smooth hand to his bloodied cheek. ‘Yes. You are dead,’ she reiterates, sliding her hand away from him and releasing his weight to the floor.

She should not have done that.

They should have said nothing.

The old man is not dead, yet.

3 THE NURSE (AND THE SPORTSMAN)

Nothing she sees is a shock any more.

Vashti checks in on the young man whose sporting career looks to have been cut short. His ankle is broken in two places along with four other fractures further up the shin; two in his tibia and two in his fibula. He wasn’t even hit or kicked, he just tried to turn around, change direction on a muddy pitch. Every other part of him obliged, but his foot remained in the position it had started in.

When the young man arrived at the hospital, he had passed out through the pain, the toes on his left foot pointing north, to Heaven, those on his right foot pointing to Hell in the south, below the floor. Now, family and friends are visiting, and he will have no recollection due to the industrial strength co-codamol and morphine cocktail in his system.

He’s nineteen and he’ll awaken to think that his life is ending.

That he has no prospects.

In the twelve years of nursing at this hospital, Vashti can almost dismiss this reaction as commonplace.

In the same way that she disregards the shock of the old woman coming in with a bruise on her ribs, caused by a fall, who suddenly develops pneumonia. Her family write it off as another in a long-line of sufferings, but she’ll be dead in two days.

Something arbitrary and trivial descending into solemnity.

She wonders whether it gets easier for the doctors to deliver this kind of news.

The way murder is supposed to become easier after your first kill.

Then she sees something different.

Something unusual.

Nothing.

She sees nothing at all.

The bed is empty; the covers untouched. The pure-white cotton sheet is folded over the paling blue blanket, which is wrapped so tightly around the mattress you could bounce a penny on it.

There’s disquiet.

It feels wrong. To Vashti, at least.

Like the things that she is seeing should not be.

Vashti pulls the half-closed curtain to the side, the rings scraping against the curved bar like the excrement raking against the pile-ridden colon of the old lady on her last whimsical visit to Accident & Emergency. She told them she was shitting razorblades. That she was crapping jagged granite.

Her family left her to deal with that alone too.

Because she is a burden on their otherwise unchallenging, fulfilled lives.

She doesn’t have any money to leave, they think, so why bother?

Vashti should have felt saddened to see such apathy towards another human being, but that is not how she feels at all; she witnesses it far too often and their lack of caring is contagious.

She can’t even remember who was in the bed before it was vacated.

Did they die?

Everybody dies.

But this time, this bed, this pristine cot, leaves her with a sense of unease. Of the unnatural. Of fate being tampered with.

It should contain a man in his eighties, recently pumped full of soapy water to evacuate any remaining pills from his pathetic failed suicide attempt. It should house the old man with his crepe-paper skin and his am I deads? and his face cut from falling and his deep-set depression.

The unfillable hole in his heart.

And the unmakeable hole in his memory.

He is somewhere he should not be. Somewhere unnatural. Somewhere else.

Kneeling in front of two angels. As they prepare to drag him through Hell.

4 GOD? TERRORIST? NARRATOR?

Do they see me?

Does anybody notice me riding around on the same circular line, never getting off at a designated stop? Am I merely, like all those on this carriage, simply unaware of my station in life? Can I sit here forever?

Do the people who perch next to me, opposite me, standing in front of me holding on to the overhead bar for balance, ever contemplate the wires that line the underground tunnels? Do they know what each one does? Can they say how long each cable is? Where do they start? Would they stretch to the moon and back?

If I had a bomb strapped to my chest underneath my jacket, would anyone spot it? Where would be the best place to detonate? Should I wait for a tunnel? Would it be more effective to have the train caved in? Would they feel the vibrations in the street above? Or should I wait until it stops at a platform?

Are the women more intimidated by my presence or is it the male population that I frighten most? Are they even scared? Have they even managed to pull themselves from their own solipsism to realise I pose a threat?

Do I even pose a threat? Is my risk physical or metaphysical?

Isn’t there always that question of reality and faith and belief?

What if I am not even on the tube? Have I ever been to London? Do I know the stations that are dotted along the Circle Line? It’s the yellow one, right?

Could it possibly be that I am not asking these questions and that a third party is forcing these words onto a page? That I am a narrator? I have no face? I have no distinguishing features? My appearance is not described in detail because I am the one who puts forth the characterisations from my invisible room in the reader’s mind?

Is that what they called omnipotence?

What, then, is omniscience?

I would know that if I was the narrator, right? Isn’t one of them to do with God? Is that correct? Is it God?

Am I God?

Are they my angels presiding over the old man? Did I send them to that maisonette to watch over a suicide attempt, allowing an elderly male the opportunity to repent, to save himself? I’d know if I was God, wouldn’t I?

You would know?

People would know?

Or is it a bit like that Joan Osborne song? What if God was one of us? What if I am one of you? Are you singing that song in your head now? Do you sometimes hear her name and think of John Osborne the ‘kitchen sink’ dramatist?

What if I am just a slob? What if I am simply here on a scam where I watch the population travel to and from work each day, spotting tourists and visitors, blending into the background so that I can pick a pocket or steal a camera or lift a mobile phone before heading home to sell my stolen goods and deceive my wife into thinking that I have been at the office?

Are there too many questions unanswered?

Should I stay on the train and wait for the old man?

Does he know the answers?

Does he have a question?

5 THE DAVES (AND THE NEIGHBOUR)

There’s nothing in the letterbox. There rarely is. The cheque is another lie. But this Dave has gone looking for it so many times, he’s forgotten that he made it up. He doesn’t know who it is supposed to be from. He has no idea how much it is for. There’s no reason he should be receiving it.

There are only six flats in the building. The ground floor is for the elderlies, it seems. Flat one is a pleasant but forgetful old man, who sits ten inches from his television screen for most of the day. He’s a year away from receiving a telegram from the queen. Opposite, in number two, are two South African women in their fifties. They’re sisters. They live together. They’re not particularly friendly.

The middle floor: flat three, above the old man, this place is always changing. One month it was six people, three generations, from Bangladesh. Eternally optimistic and friendly. The opposite of the four men who moved into that two-bedroom apartment after. Now it seems there are two couples in there. It’s difficult to know which two people go together. They seem interchangeable.

Opposite, in flat four, is the recluse. The seldom-seen woman in her late thirties. Everything she needs is delivered. She never leaves the building. There’s a sports car in her parking space that is gathering moss.

And on the top floor, the Daves are in flat five, and opposite, listening to every argument the two men have, is the neighbour.

Dave talks to himself as he goes upstairs. He says something about a stink in the corridor. That ‘fucking stink’ is him. He mumbles under his breath about the neighbour he was so congenial to moments before. It’s the other Dave who is muttering.

At his front door, he remembers that he doesn’t like being outside the flat for too long, in case the landlord makes a surprise visit and asks for the four months of rent she is owed. He fumbles with the keys, looking back over his shoulder. With a click, the door is open. He slinks through the gap, shuts the door behind him and puts the chain on the inside. He locks the door with two keys and turns another latch, which he installed himself, before jamming a screwdriver into the doorframe.

Then he shouts ‘Why don’t you fuck off?’ into the lounge.

If you were there, you’d see that he opened his mouth wide enough on the curse word to reveal his tongue. The one that exploded.

This is another of his habits. The neighbour hears it all the time. Dave creeps downstairs, unlocks his post box to reveal nothing, drags his feet back to the top floor, complains about his own stench, opens his front door, fastens a thousand locks on the other side, then shouts obscenities.

‘Who’s he talking to?’ the neighbour’s girlfriend asked on one of the occasions she was watching through the peephole, mesmerised by Dave’s eccentricities.

‘Nobody. He’s mad. He lives alone,’ the neighbour confirmed. He didn’t like how inquisitive she was being. ‘Come away from there.’

‘Maybe there’s two of them,’ she joked. ‘Maybe they’re twins. Like, old twins. You don’t really see old twins, do you? Old twins are creepy.’

‘Will you stop saying “old twins”, please, and get away from the door.’

The next time she came over, she asked, with a smile, ‘So … how are the Daves?’ And it stuck. Mad, old Dave next door became The Daves Next Door.

And the ritual continues for Dave as he turns up the television to a volume that will drown out his voice. He takes a piss and doesn’t flush the toilet. He doesn’t wash his hands. He goes into the kitchen and flicks on the kettle and puts his pissy fingertips on a slice of bread that he drops into the toaster and he gets butter from the fridge and he stares at a half-bottle of Chardonnay before walking back into the lounge, where he looks straight at the spot where a single-seat recliner used to sit but which is now occupied by a single mattress. And he says, ‘Well, what the fuck are you looking at?’

6 THE OLD MAN (AND THE ANGELS)

The stupid old man wakes up in his own bed.

And he thinks he has died.

His vision is compromised. The effects of the pills, probably. He tells himself that it is a result of the trip, travelling to another realm. This is what happens when you cross over to the other side. This is what Heaven looks like.

Blurred at the peripheries.

The world through a fish-eye lens.

Our thoughts and prayers go out to those who see only in black and white.

He is not alone. Death is not solitude. It is not perpetual darkness, nor is it endless light. In the naive, hopeful, expectant, damaged mind of the sick-with-grief old man, death is the flat in which he existed in life. It is the top floor of a maisonette in East London. E3. And he has company.

His two angels are in the room with him. His guides. The girl sits at his feet, her delicate weight barely making an impression in the thin mattress. He tries to lift his head and feels the blood rush to the cut in his cheek.

‘Ow,’ he exclaims. ‘I can still feel pain.’

The other person in the room looks at him, unflinching. His eyes bore into the old man’s, and he speaks in something between his true voice and a whisper. A hush louder than a voice, yet softer.

‘This is the first stage of your death, Saul.’

He calls him Saul. The old man has a name. He thought it would be lost.

‘The first stage,’ the man on the chair, who Saul believes to be one half of his team of guides, repeats, hoping he sounds more ethereal than usual. Aspiring to a higher level of poignancy. Of believability.

Then the old man, Saul, starts to cry.

The girl and her partner stare on in silent, unnoticeable trepidation. And say nothing.

Time passes. Haemophilic seconds bleeding furiously into minutes that feel like weeks, as it dawns on the old man that he still has the ability to reminisce. This is the curse he expected would lift with the ingestion of those pills.

All those pills.

For her.

Ada was born in 1927, two years before Saul. The old man. She had lived on Wheatstone Road in West London with her quiet mother, hardworking father and six siblings in a house only large enough for a family without any children. Or pets. Or furniture.

Or food.

They were poor and thin but not unhealthy. And the kids were generally close and not as miserable as the adults. Saul lived close by, on Wornington Road, in similar conditions.

Ada was mischievous all her life. She would lift the corner of her blind to see the planes in the air, the German bombs that rained hell over London. That had destroyed homes and buildings close by. That had fallen on St Thomas’s Church. She loved the spectacle, almost admiring their majesty of the skies. The sound had even stopped bothering her. She saw no use in feeling fear.

Even when they told her she only had months to live.

Even when she knew those months would only be weeks.

She was at her best when times were at their toughest. Many people of that time were. And she never lied. Not after the incident with the soup.

Ada had been hungry, her insides hollow at the thought of another bland, stodgy meal made from scraps and leftovers – not that anything was ever left over – and foods that should not be on the same plate but were there to make another equally beige ingredient stretch a little further. This was one of her mother’s talents.

Ada saw the sign for the soup while playing in the street by herself. It was outside a local hall or community centre or church – this part of the story was never clear because it was not important to her, only the soup was.

And the bread.

‘Real bread,’ she would say with a smile that seemed to stretch across her face as far as her mother could stretch a cabbage and some bacon. ‘I couldn’t remember the last time I had bread like that,’ she would ponder dreamily, affectionately.

They were giving away soup, not even the greatest soup in the land, but it was soup, nonetheless, with a crusty roll, at the hall or community centre or church. It doesn’t matter which. Children were being fed. Free donated food to help families where the man of the house, the father, the husband, was unable to work or was incapacitated in some way.

Ada went in and told them the lie. That her father was at home. He had no job.

And she ate that soup.

She dipped her bread into the liquid. When that had gone, she poured the liquid from the bowl into her mouth. When that had gone, she used a dirty forefinger to wipe up what was left.

What flavour was the soup?

‘I can’t remember,’ she would answer, still with that ridiculous grin. ‘Maybe chicken.’

Later that night, feeling full and healthy and tired, a knock came at the front door. Her mother answered. There were two men on the doorstep, sent from a local office to speak with Ada’s father about his lack of employment.

‘He swung me around the kitchen that night by my hair. He hit me with a belt and shouted at me for lying,’ she would tell Saul or anyone who would listen, never losing that smile or the look up to the left, as though it was being played out for her in an invisible thought bubble.

Then she’d laugh.

‘Totally worth it, though.’

On her last day she’d told her husband, Saul, that she could still taste that soup.

The old man sits on the bed, very much alive, passing time he thinks no longer exists, and recalls his wife and her favourite stories.

‘I still remember her. My memories are intact.’ His voice is much higher in pitch as he weeps with abandon. In death there is no need to restrain tears. He gazes over his paunch into his lap.

‘Where is my nothing?’ he asks solemnly, his eyes closed, still facing downwards. His heart still wrenching as it did while he was alive, he thinks. ‘Where is the dark?’

‘It will come,’ says the girl at the end of his bed, placing a gentle hand onto his blanket-covered foot in quasi-commiseration.

She repeats the sentence to inject drama.

‘But now you should lie down. This is not the hardest part. Death does not always mean rest.’ The male voice hits the old man’s face from the side as the fake angels form a pincer attack.

But he remains seated, weighted with the sorrow he believed death would erase, and he wonders why that impish, impulsive, fearless woman ever walked down his road, why she spoke to him, loved him, lived with him, died with him. Wasn’t she better than that? What did she see in him? He’d never once lifted his curtain to see the Germans fly over London. He never tasted the soup.

7 THE NURSE (AND THE SPORTSMAN)

Vashti’s unease at the empty hospital bed sits with her throughout her coffee break. It jumps on her shoulders as she takes a long draw of nicotine in a bus shelter a safe distance from the hospital. The label on the packet says: Smoking is highly addictive, don’t start.

Why does she not remember the last occupant?

Has she really stopped caring?

Desensitised to trauma.

There are no buses at this time of night. There are no people around. Yet, still, Vashti is forced to trudge across the staff parking bays – of which there are too few – and out of the hospital grounds, past the cemetery, on to the Mile End Road so that she can smoke in peace, without fear of castigation from other colleagues and the invisible threat of a health-and-safety inspector.

A smoking nurse.

A cancer-baiting health professional.

Your doctor or your pharmacist can help you stop smoking.

This is the night shift. It’s full of insomnia and screaming in pain and patients pressing their little red button because they need to go to the toilet but their doctor has not provided them with crutches yet despite the full leg cast. This is the part where Vashti takes a pan to the sportsman. Where she offers her help and expertise. Where he declines because he’s embarrassed at his current state, he believes his career is over and the last thing he wants is for a woman to witness him shitting in a disposable container.

This is the point where a physically fit, confident athlete gets stage fright. He is desperate to evacuate his bowel but is lying on his back. He feels like a child. A useless infant who has not yet learned to walk. He psyches himself out. It’s strange, Vashti thinks. People tend to just go. The sense of self-decency should be left at the automatic emergency doors along with privacy and vanity. Everybody shits in the pan eventually.

But everything tonight is peculiar. It is not as it should be. It is unnatural. The old man named Saul should be in the empty hospital bed being cared for by an intrinsically concerned Vashti.

Or he should be dead.

Somewhere in the universe, both of these things are happening.

Yet, at this moment, Saul is crying in his own bed for his deceased wife, and the nurse, the troubled and trapped health worker, laughs to herself for a moment at the inadequacy and stubbornness of the sportsman who refuses to defecate into biodegradable Tupperware.

Obstinacy may reduce blood flow and cause impotence.

Vashti is still awake on the ward at 7am. The remainder of her shift has been peculiarly quiet. Nobody has died or called out since the sportsman refused the bed pan. He has not slept either. His crutches are not due to be delivered for another three and a half hours.

That is the equivalent to twenty-four and a half days in Hell.

Or Heaven.

It is the same as three and half hours in Saul’s bedroom.

Or ninety-five stops on the Circle Line. Nearly four times round the track.

‘Good morning,’ Vashti whispers to the sportsman, the rest of the patients on the ward still snoozing through their broken limbs and inflamed joints and tumour-clad vital organs. Some in natural, oblivious slumber, others in drug-induced temporary comas.

‘Oh, God. Is it? Is it morning? Is it good?’ His response is sardonic. He raises his voice and forces the self-loathing in his nurse’s direction. ‘I told you, I can’t go in one of those things.’

‘Listen. I need you to be quiet.’ She produces a pair of crutches and within moments he is sitting up, his legs have swivelled around to the side of his bed and his arms are outstretched. This is the first time that he has remembered the pain in his leg. It shoots down from his hip to his heel; his toes are blue and without feeling. The sportsman bites his teeth together, tightening the tendons in his face and squaring off his jaw even further.

‘Shh…’ She hands over crutches. She clicks them to their maximum length after reading his height from the chart. He towers over her. ‘Do not wake anybody up. And please act surprised when the doctor comes in a few hours to deliver your real crutches. He will also demonstrate how to use them.’