7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

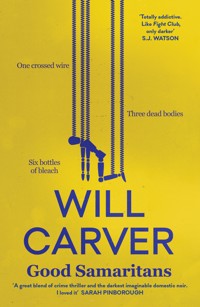

Shortlisted for Best Independent Voice at the Amazon Publishing Readers' Awards Longlisted for the Guardian's Not the Booker Prize THRILLER OF THE YEAR in GUARDIAN, TELEGRAPH AND DAILY EXPRESS 'Totally addictive. Like Fight Club, only darker' S.J. Watson 'I loved this book. Dark and at times almost comical, a great blend of crime thriller and the darkest imaginable domestic noir' Sarah Pinborough Dark, deviant and disturbing domestic noir … one of the most entrancing, sophisticated and page-turning psychological thrillers of the year… One crossed wire, three dead bodies and six bottles of bleach… Seth Beauman can't sleep. He stays up late, calling strangers from his phonebook, hoping to make a connection, while his wife, Maeve, sleeps upstairs. A crossed wire finds a suicidal Hadley Serf on the phone to Seth, thinking she is talking to The Samaritans. But a seemingly harmless, late-night hobby turns into something more for Seth and for Hadley, and soon their late-night talks are turning into day-time meet-ups. And then this dysfunctional love story turns into something altogether darker, when Seth brings Hadley home… And someone is watching… Dark, sexy, dangerous and wildly readable, Good Samaritans marks the scorching return of one of crime fiction's most exceptional voices. 'So dark, so cool' Lisa Howells, Heat Magazine 'Will Carver's invigoratingly nasty novel … is a bleak vision of life: not the whole truth of it, thank god, but true enough to impart to the reader the thrill of genuine discomfort, presented with the chilly conviction of Simenon's most unflinching romans dues and just as horribly addictive' Jake Kerridge, The Telegraph 'Carver weaves these strands together for an unsettling but compelling mixture of the banal, the horrific and, at times, the near-comic, wrong-footing the reader at every turn' Laura Wilson, Guardian 'In this frantic read in sheer overdrive, Carver appeals to the worst voyeur in all of us and delivers the goods with a punch and a fiendish sense of pace and dark humour … my type of noir' Maxim Jakubowski, Crime Time 'Must Read!' Daily Express 'Beautiful, gripping and disturbing in equal measure, a postcard from the razor's edge of the connected world we live in' Kevin Wignall 'Possibly the most interesting and original writer in the crime-fiction genre, and I've loved his books for years. Good Samaritans is his best to date – dark, slick, gripping, and impossible to put down. You'll be sucked in from the first page' Luca Veste 'Oh My God, Good Samaritans is amazing. I'm a little in love with your writing Will Carver' Helen FitzGerald, Author of The Cry 'Sick … in the best possible way. Will Carver delivers a delicious slice of noir that will have you reeling' Michael J. Malone 'If you're looking for a genuinely creepy thriller, checkout Good Samaritans… completely enthralled' Margaret B Madden 'Dark, edgy, disturbing, shocking and sexy. It's also highly original and one of the best thrillers of the year … You need to read this book' Michael Wood 'A twisted, devious thriller' Nick Quantrill 'A dark and addictive novel that felt deliciously sexy to read, like I should read it where no one could see' Louise Beech 'A pitch dark, highly original, thrilling novel. If you're a fan of Fight Club, you'll love this' Tom Wood 'A provocative, heady, unique, challenging read and it is absolutely blimmin wonderful!' LoveReading

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

v

GOOD SAMARITANS

WILL CARVER

vii

For Tuesdays

viii

ix

‘But a Samaritan, as he travelled, came where the man was; and when he saw him, he took pity on him.’

—Luke 10:33

‘When you have insomnia, you’re never really asleep. And you’re never really awake.’

—Narrator, Fight Clubx

CONTENTS

GOOD SAMARITANS

It doesn’t get you clean. Not that much bleach. Sure, there are face creams that you can buy that will help with dry skin or dark patches left from overexposure to sunlight and they’re clinically proven to help. But it’s a trace amount.

And, for those suffering with eczema, a bleach bath may be recommended. Your dermatologist will tell you that the bleach can significantly decrease the infection of Staphylococcus aureus, a bacterium prevalent in those who are plagued by this skin condition. Still, it is recommended to use no more than half a cup of bleach in one half-filled bath of water.

Because it won’t make your skin sparkle like it does your toilet basin. It will burn. It will blister. You will bleed. It will hurt like hell.

Unless you’re already dead.

It’s the moment before that hurts like hell. That drowning sensation you can sometimes experience when somebody much stronger than you forces their weight down against your windpipe. It’s the gasping for air that will hurt, not the bleach.

And then there’s that weird buzzing in your ears as you die, and your face is discolouring, which makes it easier for coroners to determine the cause of death, though the compression marks on your neck are a huge giveaway. And the way your eyes are now protruding. They won’t know for sure about your tingling muscles or vertigo, and the bleach will take care of the blood that came out of your ears and nose.

But don’t worry about the bleach, the six bottles of bleach poured into a bathtub topped up with hot water that you are dumped into and left for days. The one where you are scrubbed inside and out as the chemicals burn your entire body and strip your hair of any colour. That part won’t hurt.

So there’s no need to run your skin under cold water or wrap your wounds in plastic. But that will still happen. You will still be taken care 2of. And your fingernails will be cut and your teeth will be brushed, just in case you bit or scratched when you could still feel pain.

And you won’t be cold when you are dropped in a ditch or a field or some undergrowth with only the plastic to protect your modesty and cover your mottled skin. Of course, your body will be cold, but you won’t feel it.

It will be okay. You can just lie there. Rest.

Hope a dog-walker wanders by, or an overamorous couple lie down in the wrong place or a kid goes searching for a ball near the wrong tree.

Wait for that Good Samaritan to find you.

They will find you.

THAT WEEK

SUNDAY4

5

1

I was troubled. There was no doubt about that. The list of things I hated about myself was long and easy to compile. And, like so many people who need the support of others around them, who need to be able to talk without fear of judgement or ridicule, who need love and encouragement and positivity, I was alone. Everyone had given up. Even those who were still in my life were waiting, counting the days until that phone call would be placed to say that I’d finally succeeded and they could all get on with their lives now without Hadley Serf getting in their way.

I’d tried to kill myself before.

I’d tried a lot.

That first time – well, what everybody thought was the first time – was a classic wrist-slashing attempt. Poorly thought out and badly executed as it was, people started to sit up and listen.

I was in my flat, alone, and I’d had enough. I took a razor in my right hand, placed it on my forearm, pressed it into the skin and swiped downwards through my wrist towards the palm of my hand. I would have gone across the wrist but I’d watched a film that had very clearly stated that it was the wrong way to do it. How embarrassing to be found dead having cut your wrists the wrong way. I’d never live it down.

I only cut the left wrist, a good four-inch line in my arm, and then I called my boyfriend, who came to get me and take me to the hospital. Then he dutifully and diligently called my friends to let them know.

And they rushed from wherever they were at that point to come and see me.

And they didn’t understand it.

And it was awkward.

And it still is. Because they haven’t really bothered to dig a little deeper.

To understand just how much I can’t stand me. And that ever-growing list of things that I don’t like and can’t seem to fix. 6

They talk amongst themselves, saying that it is my father’s fault. He has always suffered with depression but won’t admit it to himself. He has always belittled Hadley. That’s what they say. And they say other things, ‘I don’t know what she’s so depressed about, her parents have loads of money.’

They yawn. They wheeze. They spit.

Of course, I don’t care about my family’s apparent wealth. I thought about my father and my mother and my younger brother before I ran that blade through my skin, unzipping a dark-blue vein that released a beautiful crimson worm. I thought about them and how much they would hurt if they found out I was dead. I thought about my boyfriend, too. And all my friends. It wasn’t a decision I was taking lightly. But I figured that, in the long run, their lives would genuinely be better, richer, without me. And I figured mine would be infinitely improved if I was no longer getting in my own way.

I cry.

I fake.

I bleed.

I had tried to explain this to my friends and they had tried to understand. They were supportive for a couple of weeks, then they thought I was fixed and they got on with their own lives again.

My boyfriend called it all off a week or so after that.

2

‘Samaritans, can I help you?’

That’s how it always started. It was his third call that night. Nobody suicidal; that was a common misconception. It was just late. People often called because all of their friends were asleep and they had nobody they could talk to. About the difficulties they were having in their relationship, or the questions they had about their sexuality, or the fact that they just felt so lonely. 7

And sometimes, not a lot, it’s a prank. Somebody who doesn’t need to talk, who doesn’t need help, who has no questions burning inside that they have no outlet for. Who, instead, think it is funny to waste somebody’s time. To interrupt the precious seconds of those in true need of assistance and companionship.

He’d had three calls already. None of them were a waste of time. Not to him. He was helping. He was there for those who needed it most.

Trying to fill that hole inside of him.

Trying to get himself clean.

His name was Ant. He was twenty-five. He had finished university and travelled around Australia, New Zealand and Fiji with his friend James. Two months into what seemed like their greatest adventure, Ant found James hanging from the back of a bathroom door, a leather belt around his neck and his dick in his hand.

It had looked like an accident, as these things so often do. And the trip was cut short as Ant helped with paperwork to get the body flown back to the UK. And, just as he was getting closer to finding out what he wanted to do with his life, Ant became lost.

Impure and hopeless.

It changed everything. From that point on, Ant just felt so goddamned dirty.

In an effort to deal with what had happened, he volunteered with the Samaritans. And now he was here, still, years later, listening to somebody who possibly wanted to go the way James had and, this time, he could help.

And when he did, in just that moment, he felt a little less dirty, a little less lost.

3

Mostly, they’d just hang up the phone.

Whoever they were. 8

Seth didn’t know.

He was just dialling a random number.

Hoping for some connection.

It goes something like this.

There are two sofas in the lounge. One for Seth, with two seats, that he sits up in. One for his wife, with three seats, that she lies down on and then invariably falls asleep – halfway through the programme that she has insisted they watch. This is called marriage. Routine. Settling down. Settling in. Settling. He tells himself that she has no idea they’re unhappy. Because it’s too pathetic to think that they both let this happen.

She misses the second half of the TV show. He watches it to the end just in case she wakes up and finds that he’s turned over to something that doesn’t turn his brain to a liquid he can feel dribbling out of his ears. What he wants to do is turn it off. Read a book. Do some exercise. Masturbate. Take one of those floral cushions from her sofa, one of the ones that really ties everything in the room together, and place it over her face, holding it down tightly so that he never has to ingest another minute of The Unreal Privileged Housewives of Some American City He Doesn’t Give A Fuck About.

He wants some warmth.

To feel loved. Needed. Wanted.

But he sticks it out. He watches it while she snores. He doesn’t remember the names of any of the characters, just like he can’t remember anything his wife likes anymore, or the reasons he fell for her in the first place.

It gets like this.

The credits roll. He wakes her up. She apologises. He says something like, ‘Don’t worry, babe. You didn’t miss much.’ Then she goes to bed. She used to kiss him goodnight but that stopped a couple of years ago. He’s pleased it did. It felt wrong. Forced.

Then he’s alone. With his thoughts and ideas and anguishes. And nobody to share them with. No one to lighten the load. 9

He wants to pick up the phone now and dial a number. But it’s too early. That’s like admitting defeat. Tonight could be the night. He could fall asleep. He could stay asleep.

He doesn’t fall or stay.

That’s how it always goes.

It’s been like this for eighteen years.

His evening continues.

He flicks through the channels with no real purpose. Perhaps the small hope that he’ll stumble across a movie where a woman is showing her breasts, because he can’t always rely on his imagination when he wants to grab hold of his cock. They don’t have sex anymore. He thinks that, maybe he’ll feel sleepy after he has come. He just feels pissed off, though. The pleasure lasts for a second. Maybe. He used to be able to control the ending, prolong it, make it last. It seems too much like work, now. It’s not about pleasure anymore.

It’s truth and nothingness. That moment when you come, when you can’t deny the pleasure of orgasm, no matter how short it is, there is an inescapable nothing. Everything in that instant is true. And he’ll take that, because all the other things in his life seem to be a fucking lie.

Seth can’t sleep. And that’s a problem. It affects everything in his life. And everything in his life affects it.

Afterwards there is a come-down. The inevitable low. Because there isn’t a thing that will top that half-second of joy. Seth’s shitty day is about to get so much worse.

Could he try harder? Should he have to? Things aren’t unpleasant. They don’t argue. She puts him down from time to time but he guesses that’s just to make her feel better about herself. He’s heard that marriage is about compromise. He figures that’s what he’s doing here. Compromising. Occasionally, he lets her make him feel like shit and, sometimes, in return, she goes to bed early.

He has ideas. They are far beyond his incredible lack of talents, but he thinks about things. All those things that he could do but tells himself he doesn’t have the time. He could leave his life. He could get out and start anew. He could pick up his clarinet and fly to New 10Orleans and play it on the streets. He could read more. And not the two hundred contemporary novels that his wife ingests every year on her commute to work and that she forgets within seconds of finishing. Important books. All those Americans that lived in Paris in the twenties who wrote things that should be read. He could learn a language. He could do anything. He has the time. He’s awake so much. It’s the state of mind that stops him.

Heart is up. State is low. Brain is racing. These three simple ingredients are enough to now keep Seth awake for the next six hours. Quarter of a day of doing nothing. He feels tired. Exhausted, actually. But somehow ultra-responsive. Stimulated. Yet with no impetus to do anything. He just wants to sleep. And he can’t.

Is this who he is now?

Who was he before?

Was he kind? Is he still?

He gives it three hours of tapping his foot and flicking through channels on the television. Half watching a programme before changing again.

Finally he concedes and picks up the phone. He flicks through the phone book, his homemade phonebook, made from a database of thousands of customers who had ordered from DoTrue, the computer company where Seth works. He found the file while fixing an error on his boss’s laptop.

Seth stops at a random page. He dials a number and waits. It rings seven times. A man picks up. He has an accent that is about seventy miles north of Seth’s home.

‘Hello?’ he asks.

‘Hey, it’s Seth. I can’t sleep. Want to talk?’

‘Go fuck yourself, freak.’

He slams the phone down at his end.

And so it begins.

Another night. 11

4

It was a cold night in Warwickshire but Theresa Palmer couldn’t feel a thing.

She’d been there for a few days, tucked away between four or five trees. People would eventually tell the tale of how she was found in the woods, because it romanticises the story; it somehow makes it darker, creepier. The local and national news, however, would flit between the use of undergrowth and copse.

The grave was pretty shallow. You’d have thought she’d have been found by now. It wouldn’t be too long. Whoever had left her there must have been in a rush. Or maybe they were simply lazy. Cocky. Didn’t want to get their hands too dirty.

It wouldn’t be long before a man would enter the woods/undergrowth/copse with a plastic bag rolled over his hand, thinking he was only going behind that tree to find a small pile of beagle shit.

Not long until that man’s body would turn cold and he would inhale nervously and knowingly.

Not long until he let out a short scream that only his faithful dog would hear.

Not long until he would call the police to inform them that he had found a body, bleached and bloated and wrapped in plastic.

It really wouldn’t be that long until Detective Sergeant Pace would discover that the woman who had been reported as missing was dead. And that she is the second person to be found like this, miles from home. Alone and dead.

Detective Sergeant Pace is a shadow.

Detective Sergeant Pace is paranoia.

Detective Sergeant Pace is losing. 12

5

Pills. It was pills the next time. It’s good to try new things.

Pills can be a great way to go. Have a drink. Swallow enough tablets to stun a small elephant. Drift off into a pain-free, eternal slumber.

When you don’t get the pills thing right, though, it is horrific.

I did not get the pills thing right, either.

My friends would say things like, ‘If she really wanted to die, she could do it properly. Get a gun. Jump off a really tall building. This is a cry for help.’ They were wrong, but that’s what they wanted to believe. Yet, still they don’t help.

I had a new boyfriend. I always thought that it would help. He was so much better than the one who had left me when the first sign of challenge presented itself. My friends liked him. I loved him. And he seemed to love me.

I was thinking about him as I popped another pill in my mouth, sitting in the driver’s seat of my old Fiat. I reminisced about our holiday to Rome, where we had crept out of our window onto the roof of the hotel and made love under the dark Italian sky with traffic buzzing around below us. I remembered him going down on me and the sound of my climax being drowned out by the horns of a thousand mopeds working their way around an unmanageable one-way system.

I recalled our smiles and laughter and his white teeth and dark skin and those muscles in his shoulders that I loved to squeeze in my hands as we kissed. And I decided that he would be better off without me in his life, dragging him down.

So, I swallowed a pill and took a drink. Swallowed a pill and took a drink. Swallowed and drank. Swallowed some more. And my eyes felt heavy. And the music on the radio was not worth listening to. Not worth dying to. So I opened the door and got out of the car but my legs were not working and they buckled beneath me. And I hit my right eye on the car door as I fell. Then my cheek grazed against the concrete where I landed. And the screen of my mobile phone cracked under the pressure 13of my body. I fished it out of my pocket and called my boyfriend to tell him what I had done and where I was. That boy who I loved.

Two fingers dug to the back of my throat and I threw up on the floor next to my face. Then I passed out. And that’s how I was found. Completely beaten by life.

The hospital said that I needed an evaluation and sent me to stay somewhere for a few days to be viewed and prodded and diagnosed. Friends visited. They said things like, ‘She got closer this time.’ And, ‘I can’t believe she’d do that to him. He’s so nice. She couldn’t have been thinking about him at all.’

But those friends still stuck by me and watched out for me, calling me every day, talking about nothing, trying to behave as though everything was normal. But everything wasn’t normal. It lasted about ten days. And that boyfriend who loved me so much lasted another three on top of that.

6

‘When did you realise?’

‘Where did that happen/what happened?’

‘How did that feel?’

Ant had these three sentences written on a Post-it note that he would stick to the corner of his computer screen. It was his routine. He would write them down at the beginning of each shift – he wasn’t always sat in the same chair. He knew them by heart. He remembered them. But having them there made him feel comfortable, like he was in control of the situation, the conversation. He had an out, if he needed it, which he never did.

He was drinking coffee close to midnight after a pretty tough call. He brought his own coffee in to work. He didn’t like the vending machine. It was dirty. And his thermos would keep his drink warm enough for hours. And he knew it was clean. It was his. That was important. 14

His last call was a man in his twenties whose father had passed away. It wasn’t sudden, the guy had been in and out of hospital over the years, always alcohol-related, but he hadn’t gone to visit him. He wanted to. He’d hated his father. Hated him for who he had been and how he had changed. And he hated that he loved him. He wanted to visit but he couldn’t.

He’d said, ‘It would have affected my family that are still alive.’ Ant wanted to push him on that but had left a short silence, hoping the caller would fill it with further information. He didn’t fill it.

‘What happened?’ Ant asked, his eyes flitting towards the redundant note stuck to the screen in front of him.

‘Liver. Of course. You know how much you have to drink for your liver to fail? A fucking lot of booze. He would do six bottles of wine in a day to himself. As a warm-up. It was ridiculous.’

Ant sat and he listened and that was all the caller really wanted. He obviously couldn’t talk to his family about how he felt. He said he was faking it in front of them. Their hatred was pure, or it seemed pure. He was the only one who felt love towards the dead man. As wrong a love as it was. He needed a release. Ant was providing that service. He was helping.

But the call ended and Ant realised he hadn’t really said too much. That was acceptable, every call was different and he had done his job well. But that caller, that estranged son with no outlet for his grief, he thanked the stranger at the end of the line for being there. That filled Ant with a warmth. A sense of fulfilment and purpose. He was cleansed.

And that caller told Ant that he would always regret not going to see his dad. Because closure was now impossible. As was confrontation with the rest of his family. He would have to live with that forever. But he was prepared and ready to do that. He would take the hit for everyone else.

Ant foresaw a caring man’s encroaching nihilism. And he feared for his future. Like he would be a one-day call – for something more serious. Something that would require Ant to participate more. And the thought turned him cold. 15

And that coffee he had brought from home, that sweet, clean, dark caffeine hit, wasn’t hot enough to change that.

He stood away from his desk for a moment and tried to push himself past his experience. His phone rang again. He sat back down, placed the headset over his ears and hit the button to answer.

‘Samaritans. Can I help you?’

7

After the first rejection, Seth liked to regroup in the kitchen. Clear his head. Make a coffee. He’s so fucking tired but he knows he’s going to be awake most of the night, so why not be a little more alert, a little more awake. He knows it is counterintuitive. He knows it makes no sense. But insomnia makes no sense.

It’s not that he doesn’t ever sleep, although that has happened – he’s had days where he couldn’t switch off and that stretched on for half a week. Being awake that long does things to you. For Seth, it begins with his vision. He starts to see everything in close-up. He could be on the couch, staring at a programme he doesn’t want to watch and all he can see is the television screen. His entire view is a 42-inch image of botoxed women flouncing around shoe shops. His wife, if she were awake, would see the screen, the TV stand that it sits on, some of the coffee table, the walls behind, part of one of the curtains. He just sees fake lips and fake breasts as he fakes interest.

The second sign that he is too tired involves a break somewhere along the wire from his brain to his mouth. Things that he’s thinking in his head come out. And things that he thinks he has said to people have only been thoughts in his mind. His wife secretly loves this phase because she can tell him that he never mentioned something and, even if Seth is sure that he did, he can’t really be sure. And, because sleep consolidates memories, he can’t truly remember. She could say anything and he has to believe her. She makes him sound like a sociopath. 16

It’s another compromise. She accepts that his mind is a mess sometimes, and he accepts that it could be her that is messing with his mind.

When people say that you should fight for your marriage, these are the things they are fighting for. Seth is exhausted and his brain isn’t functioning properly, but he knows that advice is horseshit. And he convinces himself that he did exactly that. He fought. But he’s just existing through it.

Seth’s particular form of insomnia is not about getting no sleep, it is about poor sleep. It does take him a while to get there. And the more frustrated he gets about not dozing off, the less likely it is that he will. He usually does, though. But never for long. He wakes up. A lot. Sometimes for fifteen minutes every hour. Sometimes he sleeps for two hours and then he’s awake for three before falling into a terribly deep sleep between the hours of six and seven in the morning.

He always beats his alarm. But he leaves it on, anyway. Because he still has hope. It’s all a dream. Even though he hasn’t really dreamt for years. He mostly does that when he’s awake.

In short, he can’t get to sleep but he doesn’t really feel as though he is awake, either.

Anyway, coffee helps.

The kettle whistles on the stovetop and he imagines his wife’s eyes rolling. No wonder the idiot can’t get to sleep. He makes a black coffee, no sugar – that stuff is no good for you – and he lays it down on the coffee table and he picks up the phone again.

He flicks through the phonebook once more. This time, he stops on M. F. Marshall. She lives west of his house. Around nine miles away. He’s had less hostility from the calls when his voice vibrates along a wire in that direction.

It rings four times.

‘Hello?’ She sounds awake.

‘Hey, it’s Seth. I can’t sleep. Want to talk?’

‘I’m sorry, who is this?’ Her voice is older than his. A couple of decades, at least. 17

‘My name is Seth. I’m having trouble sleeping. I have nobody to talk to.’

‘Oh, dear. There are numbers you can call for that sort of thing. I’m not sure I’d be any help in that department.’

A man’s voice shouts something in the background. M.F. Marshall ignores it.

‘Just a chat,’ he pleads, trying not to sound desperate.

‘I’m sorry, I think you have the wrong number.’

M.F. Marshall doesn’t hang up. But then a male voice snatches its way into the conversation.

‘Who is this?’ it asks.

‘It’s Seth,’ he says. ‘I can’t get to sleep.’

‘Well, you’re upsetting my wife, Seth. So would you kindly fuck off?’

He hangs up and Seth highlights the name on that page in the phonebook so he doesn’t trouble them again.

8

I’d been drinking. Alone. Again. Even though it never makes me feel any better at all.

The cat jumped in through the flap on the back door, stood in the lounge, looked at me, rolled its eyes, and moved on upstairs. I never wanted that thing. My last boyfriend bought it for me. Some kind of companionship, he thought. A replacement for the children I’d never had and he never wanted. Perhaps.

A kind gesture or a consolation.

Still, I fed it, watered it. It made its mess outside the house. We lived together but there was no companionship, no connection, no love. It was a marriage without the paperwork. Each of us waiting for the other to die.

And the cat had more chance of coming out on top.

I poured more white wine into my mouth and rolled my eyes. The 18drink was vinegary at best. A bottle brought to my house by a friend for a party. It had probably been left at their flat before it migrated to mine. You’d have to be really desperate to drink it.

I’m great at desperation.

I was in the frame of mind that had visited me on numerous occasions before. I began to think of all my friends, their individual lives and how they bettered mine. Then I told myself that I added nothing to theirs but trouble and hassle and too-much-effort.

And this is how it always started. And, this time, I had no boyfriend to think about. That was different. I always had someone. Hopping from one man to the next. Fucking up another life. As many as I could.

I know I’m pretty and smart, smarter than I let on, and when I feel good, I feel really good. I’m outgoing. Funny, even. But nothing was funny that night.

My friends were whispering to each other in my mind, looking back over their shoulders, shaking their heads in disappointment. I knew what they truly thought about the things I had done in the past. None of them had really spoken to me about it. They didn’t try to understand. They thought they knew it all.

They bitched, they sighed

And I drank some more. But there were no blades around or pills. No rope, hanging languidly from a roof beam, casting a shadow across the stool beneath. The bath was empty. The toaster was on the kitchen worktop where it always sat. Knives were in the rack. I don’t own a gun. I was on the first floor, the jump would only bruise me.

All was as it should be. But I still wanted to die.

I placed the empty wine glass back on the side table next to my purse, which I unbuttoned, unfolded and rifled through to locate a crumpled card wedged between two store cards I was nowhere near paying off.

I picked up the phone and dialled the number.

I waited for the ring tone.

It never came.

‘Hello?’ 19

9

Seth’s homemade phonebooks are thick with a rainbow of fluorescent rejections. Lines and lines from weeks and years of this idea, this hope that maybe somebody will talk back. Somebody might listen.

He stops on a page full of Turners. One is even highlighted in blue. There are three more Turners left to call. But that won’t happen tonight because he is only going to flick through to the letter S.

He drinks his coffee and looks at the television. The volume is turned down to zero and he can see enough of the area around the screen to know that the night is still young.

He flicks the pages of the book. Stops. His hand hovers above the page and his finger drops down to D. Sergeant. He runs the tip of his finger across the paper until it reaches the number he has to call. He exhales and starts to hit the numbers on the keypad. It starts to ring but he’s startled as his mobile phone vibrates in his pocket.

‘Give it a rest for one night and just come up to bed.’

He tells himself that she means well. But she doesn’t realise how unproductive that would be for him.

And then he worries. Has it really been that long? Has that six or eight weeks passed by already? Things come around so quickly when you don’t want them. Seth didn’t quite remember the last time he was intimate with his wife. Each time had blurred into one. The same old moves. And it hadn’t been intimate for a long while. Not for Seth.

And he wondered whether she even really wanted to have sex with him because she just laid there and turned her head to the side. Or moved onto her stomach so she was comfortable and didn’t have to look at him. And he thought that it was just another thing that they half did together that neither of them wanted to be a part of but were somehow too scared not to do.

And he thought that she still got the better end of the deal because he just wanted to cry. And he was relieved that she wasn’t looking at him. He felt so sick. And he somehow had to make himself hard on 20his own, with his hand, to get the condom on, then he had to get it inside her as quickly as he could before she realised that he was already unaroused. And he wondered whether she could even feel him in there.

And then he stopped caring.

She had walked back up the stairs alone. And, even though he really needed to go up to use the toilet, he’d wait. Because he’d been caught out before with no escape. A duty-bound woman, lying on a bed, offering him the opportunity to fuck a naked cadaver.

If only he could cry himself to sleep.

Things changed. They rearranged. But it all stayed the same.

Seth waits a few minutes. There hasn’t been another call, another text message.

He’s not wanted.

And he’s thankful. But he knew that was the case.

He treads carefully up the stairs, avoiding the parts he has memorised that creak under his weight. He hits the top step and peers through the open door. She’s already asleep. Or she’s pretending. There was a time he would look at her sleeping and think it was beautiful. He’d tell himself that he loved her. He’d tiptoe in, turn the bedside light off and kiss her softly on the forehead. He’d say ‘Goodnight’ even though she couldn’t hear him.

He can’t remember when or why that stopped happening. He used to think that would be his forever. But he knows now that it is this. Sneaking past a woman he no longer knows or wants. Knowing that he doesn’t belong there but has nowhere else to be, though anywhere else would surely be better.

Or maybe he does want this. Maybe it’s the tiredness talking. Maybe that takes a positive man and makes him negative.

Creeping like the idiot he undoubtedly is, he uses his phone screen to light the bathroom so he can determine the best place to aim his urine. But not straight into the water like he usually does. Against the porcelain for volume control. He pushes the flush quickly so that enough water enters the bowl to wash away the worst but with minimal 21noise. Then he wets his hands with just enough water and completes his spy mission with a quiet descent back to the lounge.

He flicks through the page of another phonebook, his hands still a little wet, and his finger drops on a new name. Ms Hadley Serf.

It’s late. The clock tells him that. He needs the clock. His body always thinks it’s time to sleep, his mind always disagrees. He dials the number and hopes Hadley’s demeanour is as beautiful as her name.

10

‘Hello?’

She was drunk. Ant could hear it in her voice.

These are the calls he fears, but wants. The calls that people assume are every call he receives. They’re not. Most suicides are men in their thirties. And they rarely call. Because they don’t know how to talk about whatever it is they are going through – grieving the loss of a loved one, separation from their wife, losing contact with their kids. The woman on the phone was suicidal.

And Ant wasn’t going to let her die.

That’s why he was there.

He could feel the sweat forming on the hairs of his armpits. He looked at the corner of his screen. The few prompts everyone in that room had memorised stared back at him. He wiped at his eyes, the sweat was relentless.

‘Have you been drinking?’ he asked.

‘Of course I’ve been drinking,’ she answered, but it wasn’t aggressive. ‘It makes everything easier. It makes doing this easier.’

‘It makes calling me easier?’ Ant knew that wasn’t what she meant; he was averting her focus.

There was a pause while she thought about what he said.

Ant covered the mouthpiece of his telephone headset and breathed deeply. He had seized control of the conversation. The thrum of noise 22in the room of all the other phone calls dissipated in a subtle buzz before disappearing into insignificant blur.

‘I wanted to end it.’

Ant was already confident of a resolution after hearing the caller use the past tense.

‘I’ve tried before, you know?’

‘What happened?’ He didn’t need to look at the note on his screen. But he still did.

‘Which time? I’ve tried a lot. I can’t even get that right.’

This was fairly common. Low self-esteem was utterly debilitating. Ant witnessed it every week in some form or another. And he’d started to hate the health industry and the way that doctors so frivolously handed out antidepressants. And the way that pharmaceutical companies were creating problems with their drugs that they would then fix with other drugs that they had also produced. And he was sick of the way social media had made people less sociable and how the great art of conversation had seemingly been lost somewhere between your latest faux-humble bragging status and your next hashtag.

And he knew that what he was doing meant something, it had a place in the world. Because people were now so busy talking that they had forgotten how to listen.

Ant knew how to listen.

He knew how to watch.

The woman on the phone went on about her difficulties, how she had attempted suicide before, how she had found a card and called him and she didn’t know why. Ant knew why. He was making her clean again.

She apologised for being lame. She must have said sorry thirty times. Her friends made her feel like she was a burden. Her family had probably done similarly while she was growing up. So everything that was wrong made her feel ungrateful, like she was moaning, like she shouldn’t be doing that. Ant told her it was not the case. It was not moaning, or complaining. It was not self-indulgent. And, mostly, he told her that she had nothing to apologise for. 23

And she needed to hear that. Deep down, somewhere, she knew it, herself.

‘Thank you. For listening. For not judging. I need to go now, though.’

‘I’m here. There’s always somebody here. What are your plans, now?’

‘Don’t worry. I’m not going to do anything stupid. I’m drunk and I’m tired and I just want to lie down and shut my eyes and wait until the morning.’

‘And that’s what you’re going to do?’

‘That’s what I’m going to do.’

Ant smiled, shut his eyes for a second and nodded. And breathed. The noise from other calls started to fill the room once more to let him know that he was safe. He saw the time on his screen and realised he had been listening for over twenty minutes. His T-shirt was a couple of shades darker through uncontrollable perspiration and he felt dirty. His lips pursed. He wanted to wash. To get changed. He had deodorant in his bag and three clean T-shirts. He was prepared.

‘Good night.’ The caller offered.

‘Sleep well.’ Ant waited for her to hang up then did the same.

He fell back into his chair; his back was wet. He unhooked his headset and turned his phone to divert. He needed to wash his entire torso. He needed it at that moment.

Ant picked up his rucksack from beneath his desk and walked over to the disabled toilet. There, he ripped off his T-shirt and threw it into the container meant for female sanitary products. He had brought his own bar of soap. There were three in there. He scrubbed his entire body, rinsed it and threw the soap away, too. He dried with one of three hand towels zipped in a separate compartment and tied it up in a plastic bag when finished. He sprayed himself and put on a new T-shirt that looked exactly like the old one. Dark, grey, unbranded and anonymous.

And he looked at his face in the mirror. His eyes were tired but he was pleased with himself. He had prevented tragedy. He had helped. It was one of those calls.

But it wasn’t Hadley Serf. He would not save her life.

Not tonight. 24

11

Hey. It’s Seth. I can’t sleep. Want to talk?

But the phone never even rang. So he didn’t get to say what he always said.

Seth dialled the number as it was written on the page. He put the phone to his ear and waited. There was nothing. Several clicks.

Then a woman spoke.

‘Hello?’

It threw him.

She asked again: ‘Hello?’

Her voice was soft. No hint of a regional accent. It was one word but she sounded nervous.

‘Hello.’ It was all he could think of to say.

‘Oh, hi. The phone didn’t even ring. You guys are fast. I guess you have to be, right?’

‘You want to talk?’

‘Is that how it works?’

‘Conversation? Usually.’

She laughed. It was absolute innocence. He’d caught her off guard. She didn’t know what to expect but she wasn’t expecting that.

‘That’s funny. I thought you’d be all solemn and serious.’

‘Why would you think that?’

‘Well, I guess you hear a lot of shit over the phone. Some messed-up stuff.’

‘Mostly just people telling me to fuck off then hanging up.’

She laughed again.

Seth felt himself smile and relax into the sofa a little.

‘I’ve never done this before. Is this what it’s usually like?’

‘Not at all. Every call is different. I’m just glad you’re still here.’

‘I’m still here. I’ve been low tonight.’ She paused and Seth filled the gap she had left.

‘I’m sorry to hear that. What’s going on?’ 25

He felt genuinely concerned. This girl, this woman, this wonderfully bright light in his otherwise dreary night was oozing melancholy from that very first hello. He sensed it. But she still had the decency to stay on the line and talk to a complete stranger. And she was being open and responsive. He wanted to know her.

‘Same old shit. You know? Some days are worse than others. My boss is annoying me. I screwed up at work a little on Friday. So did he. But it all gets shovelled downwards and I’m taking all the blame. I don’t even really like my job, but it’s the principal of it all. He expects me to just lie down and take it. Part of me wanted to fight my corner but the other part cares so little about what I do for a living that it seemed a waste of energy. That has lingered over the weekend.’

Seth found himself nodding in agreement. Then there was a silence.

‘Go on,’ he prompted.

‘Well, I just ended up taking it. Like I always do. It probably was my fault.’

She reeked of low self-esteem. It was different from his own. Seth had an issue with self-like, hers was self-worth. She hadn’t asked him about himself yet, but the dynamic already had the fragrance of codependence. And that gave him a buzz because it seemed that nobody actually depended on him.

She continued.

‘Then I spilled coffee on my shirt at lunch and I’d forgotten to charge my phone overnight so I had hardly any battery to call or text my friends. The train home was late. Blah blah blah. It’s all stuff that everyone goes through every day. Who am I to complain?’

‘You’re you. You are allowed to complain. Everything you have said is a genuine irritation. I’d be annoyed if I dropped black coffee on my clothes and my journey home was lengthened because of a leaf on the track or some other avoidable reason. If it upsets you or annoys you, you can say that you are upset or annoyed. You can talk about it.’

‘Thanks. You know, you’re very easy to talk to. You’re good at this.’

He couldn’t see her over the phone, obviously, but he knew she smiled at that moment. 26

‘Good at talking?’

‘Yes. And listening.’

There was a silence. Comfortable.

‘My name is Hadley, by the way. I’m not sure I’m supposed to tell you that.’

‘Hadley, have you never used a telephone before?’

She could hear the smile in his voice and she breathed out her own.

‘This is not how I expected this conversation to go. At all.’

‘Well, it rather dashed my own expectations, too. I thought I’d be awake for another four hours, staring at a wall, wishing I could just drift off for a few minutes.’

‘Is this how you usually talk to people?’

‘I’d like to say “Yes” but I really try not to lie.’

‘I must be special,’ she teased.

‘I’d like to keep talking to you. I’m actually wide awake right now. How was the rest of your day?’

She continued her yarn. Flitting through the mundanities of life and imbuing them with significance and poignancy. Dropping money in the road, for most, would be an inconvenience, a mild irritation. To Hadley, it was a metaphor for the decay in society and the toll we all pay for valuing those things with a price tag.

Everything was bigger than it was. Everything was heightened. Little things were important. Seth understood that.

He liked that about her.

He liked her.

This stranger who had been at the other end of the telephone line, talking about herself like he was some kind of agony uncle, like they were friends.

Friendship. Such a novelty. It might be easier if he could believe that his marriage simply lost its passion. That the spark was blown out and they were left with the friendship they had built.

When Seth met his wife, he was attracted to her physically. That’s how it starts, isn’t it? You see something you like, something shiny, and like a magpie, you want to grab it, whatever it is. You’re not friends when 27you start. You are putting forward your best face, showing them the absolute best of you. Seth had long forgotten what the best of him was. And he has no idea what it is now. Maybe his new friend Hadley is right, he’s a listener. He absorbs the troubles of others. That’s exactly what he was doing with Hadley Serf. Only, he didn’t know it at that point.

He just thought that she was beautiful. He was attracted to her, physically, even though he’d never seen her.

She told him she had drunk an entire bottle of wine that a friend had left at her house.

‘Probably on purpose. It was horrid for the first couple of glasses.’

Seth laughed.

Then he told her his name.

‘I’m Seth, by the way.’

12

Detective Sergeant Pace is alone.

Detective Sergeant Pace is disturbed.

The case isn’t moving forward. He has suspected the stepfather and the long-term boyfriend. These cases are often domestic. But the very nature of the disposal is incongruous to that train of thought.

It is calculated. Deliberate.

Barbaric.

The bleach is everywhere.

Outside and in.

To Pace, that denotes a coldness to the killer, something removed. Perhaps, even some pleasure.

He has interviewed co-workers, family, friends. Standard. Nothing is coming up. Not a bad word has been said. That is usually the case; people don’t like to speak ill of the dead. People are superstitious. But there is always somebody who will speak out, who will hint at something negative, but Pace hasn’t unearthed that person, yet. 28

This seemingly friendly, helpful, thoughtful and loving young woman was never late for work, hardly ever ill and volunteered for those less fortunate within her local area.

That local area is Bow, East London. And the authorities are drawing a blank about the possible reason her body has been found a hundred miles away in a park in Warwickshire.

News coverage has started to fade.

The public has started to move on, to forget.

Detective Sergeant Pace is not giving up.

13

‘Wow, Seth, eh? You really are a maverick. I think it is okay for me to tell you my name but I’m not sure you are supposed to tell me yours.’

‘I assure you, it’s customary.’

‘It’s my first time. I really wasn’t sure whether I should pick up the phone tonight. I’ve seen a couple of therapists. Obviously. And they just sit there. They’re supposed to be listening, but it’s not two-way. You don’t feel like there is a dynamic between you. It seems more like judgement. You know?’

I worried that Seth was overwhelmed at the ease with which I was sharing my story, my information. But he seemed unworried with the conversation, pleased almost. Not watching the clock, slowing down its movement.

‘And how does that make you feel?’ he joked. Putting on his best therapist voice, which was essentially his own voice but posher, and a bit creepier, and he elongated the last couple of words.

‘Exactly.’ I was smiling again. I looked into my empty wine glass. I wanted a drink, but not to numb my pain or help me sleep something off, or lose some inhibitions so that I had an excuse for the bad decisions I was undoubtedly going to make with the guy across the bar.

I felt good. And I wanted to feel even better. 29

‘Would you hold the line for a moment? I’ll be right back.’

‘I’m not going anywhere.’

I rested the phone receiver on the arm of the sofa and flounced my way towards the kitchen.

I felt a little lighter.

14

Seth waited a couple of minutes. It was silent. He couldn’t hear anything going on in the background. But there was no dial tone. She was coming back. He felt sure of that. The anticipation was exciting. He could feel his heart in his chest. It was quiet, he felt it beating in his ears.

‘Hey. Still there?’ She was out of breath.

‘I’m still here. All sorted?’

‘Yes. Thanks for waiting. I was fixing myself a gin and tonic.’

‘How lovely.’

‘Well, you say that, I couldn’t find any lemon. Or lime. And I’m fresh out of tonic water.’

‘Straight gin, then.’

‘Well, turns out I’m also out of gin. So I’ve been turning the kitchen upside down.’

‘Kitchen spray and Coke?’

‘I wish. Ended up with a miniature bottle of limoncello that I brought back from Italy years ago. I was going to give it to my boss but he breathed in the wrong way that day, so I kept it. For an occasion such as this.’

‘Makes sense. Although dissolving some laxatives in there and giving it to him could have been a much better use of your time.’

‘Oh, Seth, if only I had known you back then.’

‘Can you hold the line for a moment? Don’t go anywhere.’

Hadley agreed to afford Seth the same courtesy he had given her. He 30placed the receiver down on the warm leather where he’d been sitting. The phone was cordless, he could have taken it with him and continued to talk but it would just be his luck that he’d wake his wife and have to cut off the first person to engage with him properly in months.

He entered the kitchen; the tiles were cold beneath his feet. He could see two bottles of red wine in the rack, along with a bottle of mulled wine left over from last Christmas. It would be out of date before the festive period came around again but he still couldn’t bring himself to throw it out.

He was always hanging on to the things he didn’t need.

There was a bottle of Prosecco in the fridge. He knew that. It was opened on the weekend and not finished. It would be flat by now. He wasn’t even the biggest fan when it was teeming with bubbles.

It would have to be wine, he thought. But then he spotted his old hip flask, resting on a space built for a wine bottle. He picked it up, shook it, heard that there was liquid in there and he opened it. It smelled amazing. He wanted it. He poured all of it into a glass, added a dash of water from the kitchen tap and slunk back to his seat.

‘I’m back,’ he announced in a half-whisper.

‘Where have you been, I was starting to get worried?’

‘In the kitchen, grabbing a drink. I thought I’d join you.’

15

‘You know?’ I asked at the end, repeating myself like a nervous, dependent dummy.

I didn’t know if Seth had been joking again about the drink or not.

I didn’t care.

‘I wanted a limoncello with ice and water. But there was no ice in the freezer. And I’ve never bought limoncello in my life. So I settled for the water. With a little whisky.’

We talked for another forty-five minutes. It moved on from my 31wonderful brand of woes to my thoughts and likes and fears and hopes. I spoke of the present but never the future and rarely the past.

And Seth listened.

My own personal agony uncle.

‘Just in case. You know?’ I anxiously questioned again, sucking the rhetoric from my sentences.

‘You know?’

He knew. Of course he knew.

He said he knew.

And I believed him.

16

Seth was overwhelmed. He had done the same thing every night for months. He watched mindless television while his wife dropped off on a separate sofa to his. He would then flick through the channels until he was positive that she was sleeping soundly upstairs. He’d masturbate and make a cup of late-night coffee – not always in that order. And he’d flick through his special phonebook, calling people he didn’t know, hoping they would talk to him, stave off the demons of another sleepless night. If only for a short while. But tonight was different. Hadley was different.

She was a distraction.

She was a rush.

Talking to her seemed to mean something. And he had forgotten what that felt like. He had worth. His company was being enjoyed. And, while that gave his ego a boost, his mood was already slumping as he envisioned the moment the phone would be placed down and her voice would go quiet. He hadn’t spoken too much about himself but he started to wonder why she would want to continue the conversation when she realised how boring he was. How nothing he was.

Seth thought about lying, telling her that he taught a class for 32children with special needs or that he worked in research for a disease he could come up with when that information was requested. But it wasn’t in him to lie. Not to Hadley. He faked his way through life too much. With Hadley, he just had to be himself.

He wanted that.

He needed it.

Connection.