17,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

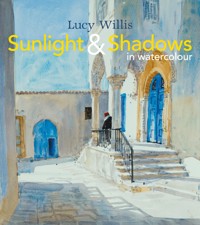

Lucy Willis is a well-known and successful watercolourist, renowned for her atmospheric paintings full of sunlight and shade. In her third book, Sunlight and Shadows in Watercolour, Lucy Willis shares her professional tips and expertise on painting inspirational landscapes and interiors full of light. There are several step-by-step demonstration paintings on how to achieve the different effects of light – bright sunlight, shadows, dappled light and night-time scenes. In addition, Lucy shows how to paint from photographs, how to mix colour, and stresses the importance of tone in creating a successful composition. The themes and subjects covered are Landscape, Water, Gardens, Architecture, Interiors, Still Life, Portraits and the importance of keeping a sketchbook. Lucy Willis encourages all watercolourists, whatever their level, to exploit the versatile effects of watercolour and produce exciting, atmospheric work of their own.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 113

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Blackberries and Apples 41 x 56 cm (16 x 22 in).

Cretan Shadows, Greece 38 x 28 cm (15 x 11 in)

Contents

Introduction

Foundations

Equipment

Handling watercolour

Practicalities

Themes and variations

Index

Introduction

As I was hunting for examples of early shadow drawings to include in this book, I realized that I have been painting in watercolour for 40 years. I left art school in 1975 and although I have continued to work with the other media in which I was trained – oil painting, drawing and printmaking – it was then that I started to experiment with watercolour.

This was also a time in my life when I had started travelling abroad to paint. In 1973, as a student, I made my first trip to the Greek islands and took with me not watercolours but a large canvas bag of oil painting equipment. I loved the experience of painting abroad, soaking up the new visual stimuli, but the resulting oil paintings were a problem. I couldn’t pack them up and move on to the next island before they were dry, some pictures became stuck together and I didn’t know what to do with the remaining blobs of paint on my makeshift palette. But in spite of this, as a little oil painting from that first trip shows (see here), I was already interested in trying to pin down the sunlight and shadows. It was only when I went to live in Greece in 1976 that I started to use my watercolours in earnest to express this interest.

North Curry Churchyard, England

36 x 56 cm (14¼ x 22 in)

The patterns cast by shadows on the ground are as important in this painting as the tree, the buildings and the leaves in the foreground.

In the years that followed, both at home in England and on trips abroad, I developed my own particular technique, never having been taught watercolour by anyone else. It is this technique that I shall attempt to explain so that, with practice and experimentation, you can use it as a guide to developing your own distinctive style.

It was probably the pragmatic reasons – the ease with which I could carry my watercolour equipment, the speed at which I could work on a painting and then pack it away – that determined my choice of the medium that eventually took centre stage for me. I have loved the way that watercolour works: its special qualities of versatility, its strength and its subtlety and the way, after 40 years, I still discover new things each time I paint.

The Abandoned Villa, Syros, Greece

Oil on paper 35 x 45 cm (13¾ x 17¾ in)

When I recently unearthed this oil painting from 1973 I was surprised to see that I was as keen then to capture the effects of sunlight and shadows as I am today.

One intriguing aspect of shadows, particularly those cast by strong sun, is that they impose striking patterns onto our familiar world. It seems that our brains have evolved to deal with this and we think nothing of it. Only when you come to paint the effect that light has on our surroundings do you realise how extreme and complicated the changes are when the sun comes out. I still take delight in analysing these changes and making visual order out of the apparent chaos of shadows.

The pictures in this book were painted around my home in England and on my travels to other countries. In 1990, after the publication of my first book about painting, I was asked by The Artist magazine to take a group on a painting holiday abroad. Since then I have led 15 trips to some widely differing locations. My most recent book, Travels with Watercolour, also published by Batsford, includes many of the paintings from those trips, and this book contains a further selection. I have been immensely fortunate to paint in some especially interesting regions of the world: in China as it started opening up to the West, in Syria just before the civil war, and in remote corners of India, Zanzibar and the Yemen.

Yet as I always remind myself, and I hope these pages will show, it’s not necessary to go far to paint light and shadows. Whether you are at home or abroad the challenge is the same: it’s a matter of seeing and understanding what is before you, and then being able to put on the paint. My explanations and demonstrations in this book will endeavour to show how this can be done.

Morning Shadows, Syros, Greece 29 x 41 cm (11½ x 16 in)

The attraction for me here was not just the patterns of the architecture but the other more elusive patterns created by the play of the shadows across the structure.

CHAPTER 1

Foundations

The City of Stone, Valletta, Malta

57 x 76 cm (22½ x 30 in)

Both the beauty and the bane of watercolour as a medium is its fluidity and transparency. Making a painting in watercolour is like walking a tightrope and juggling a multitude of balls in the air at the same time. The essential skills you need are mixing colour, adding the right amount of water, achieving depth of tone, organizing the composition, leaving white paper where you want the lightest tones, and all the while controlling the drying of the paint – not too fast, not too slow. And all this is required before even considering the knotty problem of choosing a subject and dealing with the vicissitudes of changing light and shadow!

Drawing as the foundation for watercolour

The importance of drawing cannot be over-emphasized when it comes to learning how to use watercolour. When you are attempting a painting, the last thing you want is the necessity to make corrections because you have put something in slightly the wrong place. It is important to maintain freshness in your application of the paint, which you can achieve by applying an area of colour and then letting it settle and dry without disturbing it. You need to be confident and clear from the outset, keeping alterations to a minimum and not overworking your picture by applying too many layers.

Of course, an occasional correction is unavoidable but a firm grounding in drawing technique, well before you put paint to paper, will help to keep them to a minimum. It is the best foundation for starting out as a watercolour painter and essential for training your powers of observation.

I recommend the daily practice of some small drawing exercise – a detail of your surroundings, or simply a cup on a table. Draw your subject with concentrated observation so that each exercise increases your ability to make an accurate rendition. While you probably do not want to paint purely accurate representations of the world around you, this rigour of drawing will give you the option to work in many different ways and the confidence to achieve your aim.

Later, you can try these modest subjects in watercolour, either with or without a pencil line to guide you. Sometimes it is reassuring to draw lightly in pencil on the watercolour paper first so any mistakes are made at the drawing stage before you plunge in with the paint, but if your drawing technique is sufficiently sound you may find you can plot the elements of your composition with a brush and pigment from the outset.

I found that plenty of drawing practice over the course of several years meant that when I took up watercolour I could apply the paint directly without too much risk of mistakes. Over the years this ability has developed with practice so that I can now approach quite complex subjects without preliminary drawing. You can see examples of this method in the first stages of my demonstration paintings throughout the book.

As well as studying line and proportion in your drawing exercises, you will find that tonal studies, which concentrate on light and shade, are immensely useful (see here). A lot of practice in pencil, charcoal or pen tonal drawing is good preparation for watercolour because when you come to paint you will find it easier to judge the tonal values in your subject and thus mix the right strength of a particular colour.

Using perspective

An understanding of perspective is also a key drawing skill. Coffee in the Khan, Aleppo, is a painting full of perspective problems: arches, getting smaller as they recede; the distant side of the courtyard seen just above the ornate railings; the angle of the roof planks and the corresponding shadows of the pillars on the floor. Keeping the paint loose meant I could rough in the architectural structure and the figures with blobs and washes at the early stages, only defining them firmly when the elements were all in place to my satisfaction.

The Vine Trellis, Episcopio, Greece

30 x 56 cm (12 x 22 in)

In this painting it is almost as if the shadows themselves are drawing the image and making it three-dimensional, particularly on the top and sides of the low wall where they clearly change direction according to the plane they are falling on.

While it is far from meticulously accurate, the underlying ‘drawing’ is sufficiently coherent to give the impression I wanted. I was able to concentrate on the other important aspect of the painting: the sense of being in a cool, shady spot looking out at sunshine which filtered gently through the arcade. By paying close attention to the tones – the lights and the darks – I enhanced the feeling of sunshine outside.

Similarly, The Vine Trellis, Episcopio (above) shows how drawing comes into play, not only in creating the complicated composition of trellis slats, pillars, walls and steps, but also in the pattern of sunlight and shadows throughout the painting.

Demonstration: Patsy’s Garden, England

Drawing with my brush, I usually start a painting with a pale, neutral colour (often the dregs of colours left in my palette from the last time it was used) and make small dots and dashes to indicate where things will go. I try not to make lines as they would be too noticeable if I needed to move their position. This approach leaves me with the option to change things slightly at the early stages without making too much of a mess. The marks are incorporated into the final painting as part of the general texture.

Step 1

One of the essential things to plot in an initial drawing – as important as a house, a tree or a flowerbed – is the position of the shadows. Knowing that the sun would swing round before I had finished painting this scene, I marked them in early. The shadows of the tree trunk and trellis posts and the slanting shadow on the roof were all put in with a mix of Cerulean Blue and Winsor Violet. It is these shadows, along with the others that would be fleshed out later, that ultimately give the impression of sunshine in the garden. I also blocked in the window shapes. Although the window frames were white, they appeared blue-grey in shadow.

Step 2

Another essential element in capturing the effect of sun in a garden is to contrast the foliage that has sun shining through it with that which is in shadow. My first marks included a few of the translucent leaves hanging from the tree. For these I made a vibrant yellow-green mix of Lemon Yellow and a tiny touch of Sap Green. As the second stage progressed I added more and more of these leaves and contrasted them with the dark blue-green leaves on the right. Now that the pale window shapes were dry I could over-paint them with the darker window panes. I then surrounded them with a basic pink for the brick walls made of Yellow Ochre, Cadmium Red and a touch of Winsor Violet.

Step 3

Patsy’s Garden, England

30 x 56 cm (12 x 22 in)

Gradually I built up the details, filling spaces until most were accounted for. I painted leaves on the ground with quick little strokes in a variety of colours and then interwove a green grass colour (Lemon Yellow again but with more Sap Green), making sure I did not paint over the leaves if I could avoid it. I filled in the brick wall on the left side, taking care to leave a broken patch for the hanging foliage and berries. I put a second wash of colour (Alizarin Crimson, Yellow Ochre and Winsor Violet) on the main house and started to paint a suggestion of brick texture on the right extension in a very pale version of that mix. Finally I deepened many of the tones to enhance the sense of sunshine and shadow. I put a second wash on the green of the shadow on the grassy path to darken it and added details to the house, defining bricks and roof tiles. On the right I deepened still further the dark green foliage with a strong mix of Sap Green and Winsor Violet, which really highlighted the transparent leaves beyond.

Coffee in the Khan, Aleppo, Syria

39 x 60 cm (15½ x 23½ in)

Often, when painting abroad with constraints of time and place, I paint as much of the picture as I can in the time available. I then pack up before I have a proper chance to assess what I have done. At home after returning from Syria I was able to stand back from this painting and see where I needed to add extra darks to pull the composition into focus and where my perspective might need slight adjustments to make the spaces work. All this can be done with careful over-painting.

Komito, Greece