Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

"NAVIGATING AND ENGINEERING OFFICERS REQUIRED IMMEDIATELY FOR VERY LARGE CRUDE OIL CARRIER. TANKER EXPERIENCE PREFERRED." - Lloyd's List and Shipping Gazette The advertisement captured Ray Solly's attention whilst he was on leave and demanded direct action! Viewed from the bridge of dry-cargo ships, the sleek lines of VLCCs and their potential navigational challenges always intrigued Ray – so, without hesitation, he grabbed the chance, leaving his current employer, and setting out to fulfil a dream. Supertanker examines life at sea aboard a 1970s monster where reader and author meet on board, encountering and overcoming exciting new challenges in navigation, ship handling, and cargo control. All the while, overshadowing everything else, is the awareness that this loaded ship carries around 80 million gallons of oil every day. But Supertanker is more than just the record of a new adventure. It lifts the lid on the realities of life far out at sea handling such behemoths and reveals why international safety and competency bars had to be raised.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 244

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

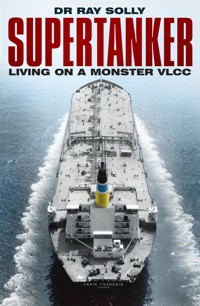

Cover illustrations: Front: An overhead view of Rania Chandris (Fotoflite) Back: A freshly painted Rania Chandris ready to set sail. (Odense Steel Shipyard)

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place

Cheltenham, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Ray Solly, 2019

The right of Ray Solly to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9285 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Chapter One Meeting the Monster

Chapter Two Surprises Along the Way

Chapter Three Problems and Personalities

Chapter Four Continuing the Learning Curve

Chapter Five The Monster Appeased

Chapter Six An Indulgence of Incidents

Chapter Seven Challenging Promotion

Epilogue

Glossary

About the Author

Other Books by Ray Solly

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I never sailed with BP Tankers, but am greatly indebted to BP Plc photographic library at the University of Warwick for their unreserved help in providing archive photographs supporting my story. These images illustrate admirably the bridge watch-keeping, shipboard operations, and lifestyle germane to tankers of all classes, but they highlight specifically the range of some of these duties performed aboard VLCCs in the 1970s.

Gratitude and fond memories are retained of both Captain ‘Tommy’ Agnew, the superb ship’s master of Rania Chandris, and Derek Allan, a chief officer of expertise, immeasurably calm patience and temperament. Serving under such officers eased my learning of a new trade.

PROLOGUE

Oil was first discovered in America in 1859 and within just three years the world’s first cargo of crude oil was carried in barrels by sea between the Delaware River and London aboard the British sailing brig Elizabeth Watts. I joined Chandris of England’s Very Large Crude Carrier (VLCC) Rania Chandris in the summer of 1973, but undoubtedly the political changes witnessed during the intervening period of little more than 100 years out of our world’s history were breathtaking. The greatest result was an almost instantaneous demand for a fuel that was cleaner, cheaper and more efficient than coal. Whilst initially the uptake occurred in America and Europe, it soon became international.

Almost immediately the sailing brig proved totally inadequate for the job. This led over the next fifty or so years to the evolution of a new brand of ship called ‘the tanker’, but equally as quickly, problems emerged that were complex and initially difficult to solve. It was soon discovered that crude oil emitted hydrocarbon gases that were both highly explosive and toxic, which made it extremely dangerous to carry by ship. But working out ways to overcome this difficulty was not the only task confronting those involved in finding solutions arising from the new method of conveyance. Transatlantic sea passages of around fifty days were involved and it became essential to transport the cargo in sufficient quantities to make the trip economically viable. This became even more important as markets expanded. Although oil was being discovered in other areas of the world, a further difficulty arose from where it appeared on the earth’s surface. These places were not only inhospitable but far removed from the refineries where it was required. Although ingenious American thinking had led early on to the construction of a pipeline, it would be many years before this method of transporting oil caught on more widely internationally. In the meantime, the only option was to rely on the ship.

Numerous experimental ‘new-fangled vessels’ (as a shipping magazine of the day unkindly described the craft) soon evolved and these underwent as many constructional changes as the human embryo. But in 1910, the English marine architect Sir Joseph Isherwood, a Lloyd’s surveyor for twelve years, devised a hull form that proved a major breakthrough. His tanker departed from the standard-built vessels to date by improving the length to depth relationship of the ship’s hull. Basically, Isherwood introduced a system of longitudinal bulkheads divided by transversals that resulted in a number of oil-tight tanks consistent with the length of the tanker. Isherwood’s designs, which he modified in the 1920s, gave the industry a stronger vessel with transversal web frames in each tank and enhanced corner brackets. It was in the 1920s also that a second longitudinal bulkhead was introduced, and the combined package produced the now conventional layout of a number of integrated sets of one centre and two wing tanks that served as a model for the standard tanker virtually without modification for the next seventy years.

By the late 1930s, a ‘standard’ tanker had evolved that was constructed on Isherwood’s design, resulting in a ship of around 12,000 deadweight tons capacity with an average length of 486ft. In 1942, demands for tankers to replace appalling losses of ships during the Second World War led to an original Esso Tanker Company design being resurrected by American yards that gave a new, quickly built and comparatively cheap tanker called the ‘T2’ class. More than 500 of these mass-produced tankers, with a capacity of around 18,600 tons and length of 439ft on a reduced draught, were propelled by steam turbine engines and served international markets. Although constructed initially with just one Atlantic crossing planned, many were still familiar sights in the world’s shipping lanes fifty years later.

From the 1950s, demands for oil exploded. The gradual transition from coal as the main source of international energy created monumental changes in private, industrial and commercial demand, which had to be reflected in an increase in the size and capacity of tankers. New building techniques fired by the American Daniel Ludwig working through Japanese shipbuilding yards saw the world’s first 100,000-ton tanker launched in 1959. Just seven years later, the first 200,000-ton tanker also appeared from Japanese yards, followed in 1968 by the world’s first 326,585-ton tanker in the shape of Ludwig’s Universe Ireland.

It was around 1973 that London tanker freight brokers, working through their Average Freight Rate Assessment (AFRA) panel acting for the chartering of tankers, divided the various sizes of tankers into categories by tonnage. They were the first to give to the world’s shipping markets the term Very Large Crude Carrier, or VLCC for short, covering those tankers between 160,000 and 300,000 tons. The British-flagged Globtik London and Globtik Japan, each exceeding 476,000 tons, also appeared on the scene in that year.

This bumper year saw the launch of a ship that would bring the industry into the public domain and help turn supertankers and a specific ship into a household name. The ship was the Jahre Viking, to use the most famous of a number of name changes ascribed to this monster. She was built by the Oppama Shipyard in Japan and was launched, after a few ownership problems, in 1975 at 418,610 tons with a length of 376.73m. In 1973 the Shell and Esso tanker companies launched what AFRA would designate the following year as Ultra Large Crude Carriers, or ULCCs, as category for ships exceeding 300,000 tons. This modest fleet of monsters owned by the two oil companies, each exceeded 500,000 tons, but it was not until 1980 that the Jahre Viking was lengthened to 485.85m, giving her a deadweight tonnage on her summer draught marks of 564,763 tons. She was the largest moving object devised by man and the shipping press all too soon ran out of superfluous descriptions in their efforts to outdo each other when they referred to her.

By the time I had joined Rania Chandris in the summer of 1973, oil had become an essential commodity with ever increasing worldwide demand: it would be no exaggeration to say that human civilisation then – and now – would simply grind to a halt without it.

CHAPTER ONE

MEETING THE MONSTER

My initial sighting of the VLCC Rania Chandris as the local aircraft from Copenhagen to Elsinore in Denmark came into land revealed what seemed to be an island attached to a large concrete jetty. Looking down on the recently completed supertanker offered a gull’s eye view. Actually seeing this vessel close up really focused my mind. I could not believe the size of it, she was colossal! I had been told by fellow mariners these vessels were the largest moving objects devised by man, but after serving as a navigating officer aboard dry-cargo ships of 7,000–10,000 gross registered tons (grt) and averaging 450ft overall length, I simply could not visualise taking this 145,000grt, 1,139.2ft long (or 347.2m, virtually a quarter of a mile) monster to sea – and being responsible for her safe navigation.

The theory of voyage planning did not bother me over-much for this would be close to the requirements normal for any vessel, apart from paying much closer attention to depths of water below the hull. Anyway, I had already made easily enough in my seafaring life a fairly difficult professional and social transition from navigating deep-sea ships to the profoundly unique idiosyncrasies then associated with coastal trading, so I did not envisage too many problems going in the other capacity direction, as it were. No, my thoughts were fired by the reality of actually seeing this sheer bulk of ship. The sight refocused concerns regarding what might confront me when entering the wheelhouse door and taking responsibility for two sea-going navigational watches totalling eight hours a day. I pondered specifically how this giant might handle under way when altering course. I tried to think positively, for at least my previous concerns of absorbing brand new cargo procedures and coping with standby operations on a massive forecastle or after-deck were forced into insignificance. I recall suddenly having ‘butterflies in the stomach’ that were completing somersaults while I was wondering just what the hell I had let myself in for. Suddenly, those smaller dry-cargo ships and a familiar way of life seemed almost friendly!

Although under way in these shots, the views correspond directly to the initial sighting of Rania Chandris as the local aircraft from Copenhagen flew over the ship as it came into land at Elsinore. (Fotoflite)

I was to discover these would not be the only shocks I experienced during the course of my following years’ service aboard this class of ship. I remain unsure to this day what prescience might have motivated me into keeping comprehensive records of nearly everything that happened professionally on board during my first three tours with Rania Chandris. Certainly, that first glimpse could not foresee how my records could indicate an international gestation period that would turn these vessels from evolutionary large crude oil carriers into revolutionary ships. Nor how concerns merely hinted at in those days regarding environmental pollution and drunken crews would lead to a gradual monitoring of social behaviour and introduce computerised systems, complex safety devices, and stringent regulations that would alter drastically the construction from single to double-hull ships, operational practices and cargo handling/engineering techniques on the world’s fleet of VLCCs. Nor could I begin even to forecast how such essential interventions might turn the oil-tanker industry into the most highly regulated form of transportation in the world. And how, in turn, this would pave the way for unexpected offshoots affecting safety aboard the products and chemical tanker fleets: dry-cargo carriers, container ships and passenger liners to affect even the laissez-faire attitude towards seafaring practices I had experienced aboard coastal vessels.

So, giving the radio officer a dry lopsided grin expressing a relaxed humour that frankly was not felt, but nevertheless outwardly sharing his clear excitement, I retook my seat and reflected on the circumstances leading to this present situation.

My adventure had begun innocently enough while on leave between voyages. During coffee one morning, while glancing through that bastion of maritime information, the journal Lloyd’s List, my idle eyes were captured by an insignificant advertisement in the situations vacant column:

Navigating and Engineering officers required immediately for very large crude oil carrier. Tanker experience preferred.

Apply to Box xxxx Lloyd’s List and Shipping Gazette.

I had always wanted to navigate VLCC-class vessels, colloquially known as supertankers, but my companies to date had served only deep-sea dry-cargo trades. Often casting almost lustful eyes, I had passed close by these monsters or had seen them on distant horizons and had chatted with officers serving aboard them by Aldis lamp or more recently VHF, so this advert jumped from the page to hit me foursquare between the eyes. A few printed words, it seemed, could possibly offer my chance. Undeterred by the ‘tanker experience’ aspect (or lack of it) but prepared for disappointment, my application was in the post next day.

Just two days’ later, a phone call invited me for interview the following day ‘if, of course, you are available’ with Captain Ivan Branch, the marine superintendent serving Chandris Tankers of England, at 5 St Helen’s Place, Bishopsgate in London. It seemed the shipping company based in Piraeus, Athens, were owners of a number of cruise liners (for which they remain renowned), plus a second fleet of assorted 7,000–8,000grt dry-cargo and product tankers. This London–Greek concern was expanding its existing collection of VLCCs and had purchased the latest addition from an ambitious Maersk Line that seemingly had over-ordered. At 286,000 summer deadweight tons (sdwt), Rania Chandris was to be the company’s largest vessel, hence flagship of the fleet, and would carry its senior master as commodore. Having just been launched, she was lying in the fitting out berth at Odense Steel Shipyard, Elsinore, some 20 miles north of Copenhagen, Denmark, awaiting completion.

The super paused before examining my qualifications, discharge book and record of sea service to date and asked bluntly, in ‘a seamanlike manner’: ‘Why have you applied for a position for which you are not even remotely qualified?’

I answered quite simply: ‘I always wanted to serve aboard tankers and applied to Caltex among a few dry-cargo companies, but one of the latter was first to offer a deck cadetship so this was accepted. I remain enthusiastic about tankers and believe the fundamentals could soon be learnt.’

Taking this on the chin, he gave me a penetratingly direct look and mentioned it might be helpful to me (and the ship!) if I would consider joining as an extra officer for one voyage until I could be trusted with my fair share of cargo watches.

‘Your saving grace,’ Captain Branch continued, ‘lies in the amount of time still outstanding for the tanker to complete her fitting out, and anyway – should we both agree to your joining – then being on board over this period would offer excellent opportunities for you to learn general tanker routines and become acquainted with the structure of the ship prior to working with Danish officers and ratings during sea trials.’

It became apparent that afterwards I would join the other officers attending the handing over ceremony – and share its delicious celebratory dinner. Then, even before ink had dried on the certificates and with the Danish flag changed for the Red Ensign, she would sail for the Arabian Gulf and my subsequent tour of her maiden and second voyages.

As our interview progressed he elaborated on the manning scales. Chandris was comparatively unique as a VLCC owner because the company deck-officered ships of this class with a master and four permanent navigators. This was unlike many contemporary oil majors, who usually retained voyage traditions of three deck officers, often putting on an extra man for the run after Las Palmas when tank cleaning took place. They would then, if the tanks were completed ready for preloading inspection, fly him home either from Cape Town or an appropriate Arabian Gulf port.

Captain Branch’s brows furrowed while clearly coming to a further decision. Looking directly at me (once again), he advised, ‘Basically, if you are prepared to join the ship on third officer’s salary and doing his job then, after a first tour of two voyages totalling about four months, you would go on two months’ leave hopefully to be promoted upon your return for further tours.’

I rather liked the way he assumed we were already professionally wedded – it seemed to imply (and inspire) an inordinate measure of confidence with me and in me! He concluded that were I happy with his offer then I could sign a contract and in a few days the company would fly me out to Odense.

Distant sightings of numerous VLCCs while on passage aboard dry-cargo ships had whetted my appetite to serve on ships of this class. (Fotoflite)

My agreement and signing of the already prepared papers took only a few seconds. As I was in London where this new building was registered at Lloyd’s Shipping Registry, and on the Shipping (Officers) Federation pool in nearby Mansell Street, a quick call could be made for clearances, including a medical. Phoning my dry-cargo employers next day, they were far from happy with my unexpected decision to part company with them: in fact, they were livid. However, having cast my die, five days’ later I was at Heathrow, having arranged to meet our radio officer to board a BEA jet taking us to Copenhagen for an onward local flight to join the ship. It seemed Sparks and I, along with the other officers, would be berthed in local lodgings for a few days until our accommodation on board was habitable.

* * *

Ben, our Sparks, was an experienced radio officer employed by Marconi Marine, who supplied the radio equipment for the vessel. He was about 50 years of age, and married with teenaged children. This would be his first experience of tanker life and I found myself warming to his cheerfully relaxed temperament.

Our arrival at the lodging house was fortuitous, for we just had time to go into our comfortably adequate rooms and unpack before the remainder of the officers arrived from the ship for supper at the end of a lengthy days’ work. Meeting new colleagues over the deck officers’ table was little different from the norm with which I had been accustomed since joining that transient existence constituting the Merchant Navy. My immediate contacts socially had to be these other mates with whom I would work directly, taking friendships with the engineers, Sparks and the chief hunk (or steward) as these occurred. So we initially appraised each other quite warily, for there always resided a doubt regarding personalities, and how these might or might not intermingle over what could prove a potentially lengthy trip. But, as the meal developed with neutral experiences exchanged larded with adventures of past ships and voyages amidst numerous humorous anecdotes, so came the inevitable thaw. By the time we had finished coffee in the lounge each of us had agreed privately that the other was ‘probably going to be worth living with’.

Derek, the chief officer, my immediate working boss, was a few years older than me, happily married with a young family and living in Devon. Similarly to the master, chief and second engineers, he had served his career to date aboard tankers and had also been recruited following an advert in Lloyd’s. Having joined the ship nine weeks’ previously, his inducement to sign on had been a promise of promotion to his own command of a later VLCC. I took to his quiet, warmly pleasing disposition immediately and felt inspired by his accepting confidence, so looked forward to learning and being guided by his vast tanker experience. Paul Tenbury, the second officer, was another tanker man. Recently married, he had been promised that on subsequent voyages he could bring along his wife, with the company generously footing the bill for her travel costs. We awaited the first officer, whom we understood was called Tim Wheeler, an ex-Mobil chief officer, who would be joining in a few days’ time. Surrounded by all of this professional experience, I felt very much the ‘new boy’, although reassured that my colleagues would offer their help until I settled into new routines.

I stayed ashore that first night exchanging further reminiscences with the master of the vessel, Captain ‘Tommy’ Agnew. I had noticed over the meal table he had kept a wise silence, but was aware of his shrewd eyes taking in the interactions between his deck officers. Such casual chatting with him over a glass or two of Danish lager soon put my mind to rest. His open uncomplicated smile, direct eye contact and air of measured friendliness immediately drew my personality towards him. I had captured what seemed to be an amused glance flickering across his features as he listened to our conversations and guessed he had detected instinctively something of my uncertainty and appreciated the cause. Quite soon into our casual chatting he asked me directly if I had seen the ship from the aircraft and, taking my affirmative on board, gently pointed out: ‘You will find, Mr Solly, the sea soon cuts her down to size once away from land, even during your first solo bridge watch. Then, once deep sea, you will see that she will handle much like any other vessel, but you’ll have to think ahead more than on a smaller ship before altering course. It would help your confidence were you to take her off automatic pilot now and then, put her on manual and “feel” the handling of the vessel in ballast and under different loaded conditions.’

Captain Agnew, an ex-commodore master from Esso Tankers, was the finest among many highly professional captains under whose command I served. (J. Shou)

He did not have to add ‘Don’t worry’ – for I was not! The master confirmed Chandris Tankers was ‘a good firm to work for’, particularly with its manning arrangements of an extra deck officer because this freed the mate for permanent day work, of which he assured me (with that warm grin I would come to recognise only too well) ‘there was a-plenty, and not only for Derek but also all of you mates!’ He told me the company followed normal maritime practices for navigating officers, so I would be responsible for the eight-to-twelve watches, having taken over from the first officer and being relieved subsequently by the second.

Captain Agnew’s perspicacity was not misplaced. He had served his entire sea career with Esso Tankers and had retired recently as their commodore master. As a deck cadet and then navigating officer aboard VLCCs and their larger ULCC cousins, since leaving nautical college he had been promoted along with the capacity of the ships. When the 30,000 tonner was a ‘large’ tanker Captain Agnew had served upon this, up to command of their 500,000 tonners. As I would discover, this wide experience with diverse tanker officers and crews had bestowed an ability to formulate pretty accurate assessments of fellow mariners. It seemed word of mouth between company directors’ had led him to apply to Chandris Tankers of England even before drawing his first payment of Esso, Merchant Navy Officers’ and State pensions. He told me later as we became more acquainted that, until the ship experienced a later flag change, he was paying his entire Chandris salary in UK income tax!

Living ashore was inconvenient but palatable. The Odense Steel Shipbuilding Company provided us with a large house sufficient to take the captain, navigating officers and our eight engineering officers, sparks and a chief steward each in separate rooms, but sharing communal showers and toilets. Until the ship was habitable, the steward was expected to keep the hostel accommodation clean, including linen changes, while we officers worked aboard the tanker during the day. He also liaised with the ship’s agent to provide food for the evening meal and a varied light lunch of sandwiches and assorted ‘goodies’ plus a battery of vacuum flasks that we took aboard each morning, although the company provided him with a non-resident afternoon cook.

My next surprise came the following day. Following a leisurely breakfast, I joined the others to climb into a minibus for the drive to our ship. Turning the corner, my first close-up impression of Rania Chandris was again of absolute sheer size. We drove alongside a solid cliff of black steel hull that dwarfed the surrounding sheds and seemed to continue into eternity. A makeshift lift took us slowly upwards on the lengthy journey to the main deck. Leaving the lift forward of the manifolds, I was confronted by a maze of massive blue-grey piping and steel-grey deck, above which grew an enormous expanse of white accommodation adorned with strident red 2m-high NO SMOKING notices splattered across the front. My face doubtless expressed the complete awe swirling within me for I caught a lopsided grin (but no further comments) from Captain Agnew. My thoughts refroze at the idea of taking this monster to sea and learning and working with the functions of the pipework: the very notions seemed preposterous. I felt totally insignificant, caught up in casual chatter of the other officers as we walked alongside the four 5m-high main cargo pipes and catwalk containing red fire monitors towards our new home.

The combined wheelhouse/chartroom was on the seventh deck. Navigating officers cabins were on the sixth deck, or D deck, and the engineering officers, including the chief, berthed on the fifth, C, deck. An internal lift took us to our deck, where my cabin was on the port side of the lift sandwiched between Paul, the second officer, and Tim, the first, who was berthed in the pilot’s cabin directly opposite the lift entrance and access to the wheelhouse companionway. Derek’s larger suite of rooms was on the opposite port side to the master. On very rare occasions when we berthed a pilot overnight, he was placed either in one of the single cadet cabins or the ship’s hospital. Ben, the radio officer, and his shack were on the after part of the port side. Captain Agnew chattered away happily as he pointed out my cabin. He was plainly in his element! After my very compact quarters aboard dry-cargo vessels I was astounded at the large size of this accommodation. The cabin was airy and pleasingly furnished with light-blue Formica bulkheads, a matching soft-seated chair and settee (which traditionally was called a ‘day bed’) and a wide double-berthed bunk. A massive desk adjacent to a large window looked singularly lonely adorned with merely a telephone and angle-bracketed lamp. Just inside the cabin door was a cubicle containing a toilet and shower. The master’s suite of rooms was next along on the starboard side looking forward, with two cadets’ cabins, study and toilet running aft, although we did not carry either deck or engineer trainees on this voyage.

Leaving the jetty lift and walking from gangway towards accommodation block presented an impressive view. (Ray Solly)

The disposition of cabins on the navigating officers’ ‘D’ deck.

A combined wheelhouse and chartroom disposition typical of many VLCCs.

A drawing from the ship’s plans of Rania Chandris showing the layout of the after part of the vessel. The height from keel to top of funnel was 210ft (64m).

Glancing across the main deck from my cabin windows, my recent apprehension returned, batting backwards and forwards like the proverbial yo-yo! I reflected how restricted were views from the wheelhouse of my dry-cargo vessels and again pondered how this unbelievable monster would react under her helm. My jumbled reverie was broken by Derek giving the customary perfunctory knock, as he popped through the open door and casually dropped two ship’s plans onto my desk for me to study and retain. One was a General Arrangement (GA) plan that gave full deck, accommodation and tank layout details, and the other was a Capacity plan – and with each I was to become all too familiar. He later gave me ship’s copies of lifesaving appliances (LSA) plans, for which I would be directly responsible, along with deck, sounding pipe and other plans of the vessel.

Before settling to studying these, I went up a deck into the wheelhouse to satisfy my curiosity concerning the ship’s navigational gear. There were no shocks here and, having previously instinctively noticed two radar scanners while glancing at the accommodation block, saw our two sets: a conventional Decca Relative-Motion job on the starboard side of the main control panel, plus a very sophisticated Marconi True Motion ‘all singing and dancing’ computerised anti-collision set. The chart table was defronted by a thick black curtain, to restrict the shaded light to the chartroom area and prevent this interfering with keeping a proper lookout in the wheelhouse. This quick glance also captured the ubiquitous Mark 21 Decca Navigator and Marconi Lodestone Direction Finder common to virtually all ocean-going ships. The familiar layout of navigational instruments, traditionally poised angle bracket lamp over the chart area with its subduing light switch, and standard two chronometers helped me feel more a part of this colossal adventure.