Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Nick Hern Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

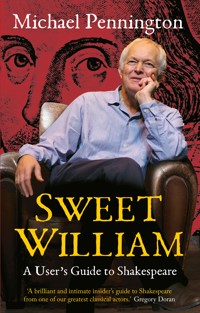

Michael Pennington's solo show about Shakespeare, Sweet William, has been acclaimed throughout Europe and in the US as a unique blend of showmanship and scholarship. In this book, he deepens his exploration of Shakespeare's life and work - and the connection between the two - that lies at its heart. It is illuminated throughout by the unrivalled insights into the plays that Pennington has gained from the twenty thousand hours he has spent working on them as a leading actor, an artistic director and a director - and as the author of three previous books on individual Shakespeare plays. With practical analysis, wonderfully detailed and entertaining interpretations of characters and scenes, and vivid reflections on Shakespeare's theatre and ours, the result is a masterclass of the most enjoyable kind for theatregoers, professionals, students and anyone interested in Shakespeare. This book was published in hardback as Sweet William: Twenty Thousand Hours With Shakespeare. 'A brilliant and intimate insider's guide to Shakespeare from one of our greatest classical actors' Gregory Doran 'Michael Pennington is a great Shakespearian actor who writes with the authority of an academic. His book analyses the plays, the characters and the playwright's life. It will intrigue, entertain and challenge students, actors and their audiences' Ian McKellen 'Rich and informative, and something that will be mined for many years to come by anyone interested in Shakespeare and in British theatre' Professor James Shapiro 'Shakespeare comes wonderfully to life in Michael's beautifully written book' Rupert Everett 'Irresistibly readable' Peter Brook

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 635

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Michael Pennington

Sweet William

A User’s Guide to Shakespeare

NICK HERN BOOKSLondonwww.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Dedication

Preface

Introduction

1

The Rose of Youth

Sweet William – Poor Inches of Nature – William Page – Moth – Arthur – Marina – Perdita and Mamillius

2

The Only Shake-Scene

John Shakespeare – Marriage and Flight – A Motley to the View – London – The Two Gentlemen of Verona – The Comedy of Errors – An Upstart Crow – Henry VI – The Rose

3

Myself Alone

The Soloists – Richard III – King John

4

The Tide of Blood

Henry IV Part One – Henry IV Part Two – Henry V

5

Love, Love, Nothing But Love, Sweet Love

Fools for Love – Love’s Labour’s Lost – The Merchant of Venice – The Taming of the Shrew – Much Ado About Nothing – Romeo and Juliet – A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Interval: The State We’re In (Part One)

6

The Great Globe Itself

Hong Kong – The Globe – Hamlet – As You Like It – Measure for Measure – Julius Caesar – The Merry Wives of Windsor – Othello

7

The Time’s Plague

The Wisest Fool in Christendom – Macbeth – Timon of Athens – King Lear

8

Your Actions are My Dreams

The Conscience of the King – The Winter’s Tale – Cymbeline

9

Love is Merely a Madness

Antony and Cleopatra – Helena – Troilus and Cressida – Coriolanus

10

Let’s Bear Us Like the Time

Ice and Fire – The Tempest – Henry VIII – The Two Noble Kinsmen – The End of All

Conclusion: The State We’re In (Part Two)

About the Author

Copyright Information

For my parents

Preface

Whatever their angle of approach, Shakespeare books could hardly be unaware of each other. So I have learned from – and had suspicions confirmed by – Peter Ackroyd, Andrew Dickson and Charles Nicholl, and by Professors Jonathan Bate, Stephen Greenblatt, James Shapiro and Stanley Wells. My thanks as always to Nick Hern, editor par excellence, and to Nick de Somogyi, a fine and genial Shakespearian sleuth who can spot a textual inaccuracy at twenty paces. It is hard to imagine this book getting to this point without Prue Skene; Mark, Louis and Eve Pennington have refreshed views of mine on the plays that I thought forever entrenched, despite or because of being, in two cases, fifty years younger than I am. There are many others who have encouraged me, at work and play and over a great space of time; they are too numerous to mention without offence to the unmentioned. I was about to say that they know who they are, but in many cases they don’t; actors and writers are heartened by all sorts of people they never even meet.

As for the chronology and dating of the plays, I’ve always thought it was, beyond a certain point, something of a mug’s game. So I haven’t supplied a conventional list of speculative dates. Given the circumstances of Shakespeare’s working life, the moment of a play’s composition is likely to be immediately before its premiere; but the date of publication can be a very different and quite vexing matter. So while the birth of a handful can be happily identified by the date of their first recorded performances, that of others can only be established as being some time before a known event, such as publication, or after another, such as some topical reference in the play. In the face of only the vaguest consensus, I tend to fall back with a shrug: after all, unlike the scholars, I feel no special burden of proof here.

The search is in any case less interesting than you might think – or than it would be with another author. Outside of his Sonnets, Shakespeare’s lived life seems to have left very little mark on his work; and as a writer he seems to have arrived fully formed, both inspired and fallible. Throughout his career the supreme and the rough and ready sit side by side: in among ‘apprentice’ works like Henry VI and King John lie masterpieces such as A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet. Tone of voice is no more reliable: the great tragedy of Hamlet is immediately followed by the comic glories of Twelfth Night. Nor is theme: the treatment of marital jealousy in The Comedy of Errors (1594) has something in common with The Winter’s Tale (1611). Throughout, Shakespeare maintains a resolutely private stance – what Chekhov later identified as ‘autobiographobia’. He wrote a series of comedies directly after his son’s death; on establishing himself in London he bought a house in Stratford, and on the point of returning to Stratford he bought one in London.

Still, the rough sequence of events seems to have been this. Shakespeare arrived in London in 1592 and wrote plays for just over twenty years: occasionally, at the beginning and end, with a little collaboration. His debut may have been with The Two Gentlemen of Verona – or it could have been Titus Andronicus, or The Taming of the Shrew, or one of the Henry VI plays. Of the twenty-five or so he wrote in the first half of his career, roughly up until the death of Queen Elizabeth in 1603, a large proportion are history plays – indeed with the exception of Henry VIII, all his ten Histories lie in this decade. This period also features some boxoffice favourites – The Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing, As You Like It, Julius Caesar. In the second phase the pace slows down from approximately two to a little more than one a year – if you can call Othello, King Lear, Macbeth and The Tempest any kind of slowing down. When plague struck, as it regularly did and closed the theatres, Shakespeare wrote poetry – primarily The Rape of Lucrece, Venus and Adonis and the Sonnets which he finally collected together for publication in 1609.

In 1599 the Globe Theatre opened. In 1603 Elizabeth I died and James I succeeded – a most significant date to keep in mind, in my view. In 1609 Shakespeare’s company began to use the indoor Blackfriars Theatre, though they continued to play at the Globe in the summer. The Globe burned down in 1613, and was rebuilt the following year. Shakespeare died in 1616. The first complete edition of his works was published in 1623. The new Globe was closed, as was the Blackfriars and all other London theatres, by the Puritans in 1642, and was probably destroyed in 1644. The Blackfriars was demolished in 1655.

The quotations in my text are not consistently taken from any particular Folio or Quarto, but are the versions I have myself become used to: editorial comparisons and textual variants are available elsewhere. The section at the end about phrases Shakespeare invented owes something, though not all that much, to Bernard Levin. I have T.S. Eliot to thank for the insight into Charmian’s dying line in Antony and Cleopatra, and Philip Franks for his recollection of Donald Sinden’s Benedick All mistakes and eccentricities are, of course, my own.

Michael Pennington

Introduction

In 1827 the composer Hector Berlioz went to see an English company perform Hamlet in Paris. He’d never seen a Shakespeare play before – in fact he spoke no English – but that evening he fell in love with the play, with the author, and with Harriet Smithson, the actress playing Ophelia:

Shakespeare coming upon me unawares, struck me like a thunderbolt… I saw, I understood, I felt… that I was alive and that I must arise and walk.

I have little in common with Berlioz, but Shakespeare hit me like a hammer when I was eleven. I had the advantage of speaking English, but no more natural affinity with Shakespeare’s world than might any other Tottenham Hotspur supporter of that age. The play was Macbeth, at the Old Vic Theatre in London, and it certainly wasn’t my idea to go; and my parents, who took me, were only supposing in the vaguest terms that it would be Good For the Boy to see a Shakespeare play at some point before adolescence carried him off into the unknown.

Little did they guess. The show started with a bloodcurdling scream that came slicing out of a darkness which then lifted to reveal a bloodsoaked soldier staggering towards us and collapsing; and a moment after that, from a tangle of dead trees and twisted branches behind him, the figures of the three weird sisters arose to ask when they would meet again in thunder, lightning or in rain. Two lines in, I was on the edge of my seat; and, the play being what it is, I stayed there all night. Macbeth was played by the fine Paul Rogers; as he contemplated the murder of King Duncan, he also saw what he was about to do to himself:

Besides, this Duncan

Hath borne his faculties so meek, hath been

So clear in his great office, that his virtues

Will plead like angels, trumpet-tongued, against

The deep damnation of his taking off;

And pity, like a naked new-born babe,

Striding the blast, or heaven’s cherubim, hors’d

Upon the sightless couriers of the air,

Shall blow the horrid deed in every eye,

That tears shall drown the wind.

I couldn’t quite work out this wonderful picture, but its power and fluency sounded like a great rumbling organ with all its stops open. A few minutes later Macbeth saw his imaginary airborne dagger and followed it – slowly, slowly, slowly – towards Duncan’s bedroom to do the deed:

Thou sure and firm-set earth,

Hear not my steps, which way they walk, for fear

The very stones prate of my whereabout

And take the present horror from the time

Which now suits with it…

Even then I knew that I was looking at an actor in property boots moving across a painted stage floor; but what I heard was the sound of their weathered soles on the flagstones of Glamis Castle, and I fancied I could feel the cold and the dark and the silence swirling around its battlements. Why was this man, so terrified but so delighted, indulging his fancies when he had such a single, brutal thing to do?

While he was about it, Ann Todd as Lady Macbeth thought she heard something untoward:

Hark! Peace!

It was the owl that shriek’d, the fatal bellman

Which gives the stern’st good night…

I caught the jagged phrasing: the shriek of the owl and the soft pounding beat of a solemn bell, both sounds held in the same instrument like the chanter and drone of the bagpipes.

Later on, darkness fell once more on the murderous but strangely sympathetic couple as they prepared for their banquet:

Light thickens, and the crow

Makes wing to the rooky wood.

Good things of day begin to droop and drowse

Whiles night’s black agents to their preys do rouse.

Nowadays I recognise with some affection Shakespeare’s profligacy – with the crow established, he hardly needed the wood to be ‘rooky’ as well; but since he was bringing night onto an open-air stage in the middle of the afternoon he perhaps needed to rub it in a bit. And as always with him, there’s a subtler possibility: the crow is solitary and the rook social, and Banquo, with only his son for company, is about to be mobbed by a flock of assassins. I also know now that what makes the passage work is the brooding rhyme of ‘drowse… rouse’, its broad vowels opening out from the tight consonants of ‘makes wing… rooky wood’. All I was aware of then was that darkness was closing in on Banquo as it had on King Duncan; I heard wings flap above my head and had the distinct sensation that I was growing up fast. Not to mention wanting to know how they did all the blood, and quite how that empty seat at Macbeth’s dinner table had become scarily filled without my noticing.

It’s remarkable how often in this play we are asked to imagine dreadful things just out of sight. Once Lady Macbeth, her sleeping eyes blindly open, had left the stage, I could almost hear her breath stop while Macbeth looked at us as if through a doorway of hell:

I have liv’d long enough; my way of life

Is fall’n into the sear, the yellow leaf…

I had no idea what ‘the sear’ was, but it had a tearing sound, like something that would never be mended again. But I knew well enough about the yellow leaves. Only a few hours before – a lifetime by now – I’d seen them as I trudged home unwillingly (for once) from school, knowing I had to go to this damned Shakespeare play that evening. It was quite a nasty autumn night, and the leaves from the plane trees on our street had blocked up the gutters under yellow streetlamps that made the pavements look yellow too. So this time it wasn’t at all the grandness of Shakespeare’s language that caught me but its near-at-handness, its easy presence in my world. Especially as I heard the bleak abstracts that followed:

And that which should accompany old age,

As honour, love, obedience, troops of friends,

I must not look to have; but in their stead,

Curses, not loud but deep, mouth-honour, breath,

Which the poor heart would fain deny, and dare not.

The play had begun with a scream, but now Macbeth’s self-damnation was in whispered, ordinary words: though I was only eleven and certainly hadn’t killed anyone, I understood what he felt about his life falling like autumn leaves.

Back home again and safe, I was like a child possessed, and my parents must have wondered if they’d ever hear comforting talk of Tottenham Hotspur again. I hooked Macbeth off the shelf and straight away, that night, started reading it aloud. And for days, weeks and months to come I kept trying Shakespeare that way – for years really, as I still can’t read him in silence. I began to feel the oscillations in the language and the headlong narratives, events tumbling impatiently over each other as if intervening scenes in real time had been cut out. I saw a mind full of scorpions, a woman sensing devils murmuring in the room around her, the dead rising shrieking from the earth; but the play’s most famous speech, about the tale told by an idiot, is, once it gets going, almost monosyllabic, a bulletin from a man glimpsing infinite, purposeless tomorrows. At the same time I was trying to find out whether the sound, so splendid but so intimate, would work coming off my tongue as well. And in fact it did, sort of, and so that was a first lesson learned: even a speech like that belonged to me, with my childish treble going on adolescent croak, and not just to the experts.

Now I’m an expert of sorts myself, having at a rough estimate spent twenty thousand hours of my life so far performing Shakespeare, leave alone the time taken rehearsing, talking, thinking and writing about him. So I know quite a bit about the torque of the engine. But sometimes during a performance I see a bespectacled eleven- or twelve-year-old down near the front, and it doesn’t half make me raise my game. That’s when I realise that all I’ve learned over the years doesn’t add up to a hill of beans unless I can do something very simple with it: pass on to him or her that same intoxication of sound and meaning, its sudden impact on ear, eye and stomach.

In between, Shakespeare has been as pervasive in my life as white noise. If Jaques was right about the Seven Ages of Man, then having spent my First in routine mewling and puking, encountering the plays in my Second had made me not so much the whining schoolboy as a thoroughly narrow-minded adolescent who had soon, to his own satisfaction and unthreatened by any audience, played everything from the Bawd in Pericles to Old Adam, from Titus Andronicus to Falstaff’s Page – which I suppose has saved a lot of time learning the lines later. So, when the Old Vic put on the three parts of Henry VI for a short run that lay entirely inside my boarding school’s term-time, you may imagine my shock at being refused leave by my headmaster to go home for a single day and night one weekend so that I could see a couple of them. He acknowledged that it would be ‘a valuable experience’ for me but was afraid, he explained to my father, of ‘setting a dangerous precedent’. A dangerous precedent? Oh, happy dream – scores of young adolescent males rushing to see Shakespeare’s least popular history plays rather than knocking each other’s heads off on the rugger field. I still remember the dates we’d asked for, since I spent the hours of the performances facing more or less east, imagining the whole thing from the middle of Wiltshire; meanwhile my father, though terrified by his son’s interest in show business, never forgave the headmaster for his elementary failure of vision, for such an illiberal reflex.

As for the Third of the Seven Ages, I was the lover in due course, sighing like furnace as Mercutio and Berowne, Shakespeare’s great young fantasists I played at the RSC during the 1970s; and by the military Fourth, I was a hardened campaigner, sometimes bearded like the pard and frequently uttering strange oaths, asserting my own and Michael Bogdanov’s views through our maverick outfit, the English Shakespeare Company. This was when I really started to learn something, for instance from playing in Richard III in East Berlin in 1989, towards the end of the Honecker regime, to an appalled silence: the glimpse of Richard’s iron fist gleaming inside his velvet glove was not the merry irony it can be to Western audiences but a horrible daily fact. The silence would be broken minutes after the curtain each night as local actors, and not only actors, stormed backstage and wouldn’t let us leave till we had all drunk and talked together for several hours.

Around the same time, I directed Twelfth Night with a Tokyo company in Japanese. I got on well with everyone except Toby Belch, the company’s oldest member, whom I found very difficult until we went for a drink one night soon before the opening. Amidst the smoke of the yakitori barbecue and the fizzle of the Suntory he told me what of course I should have guessed: he was old enough to have served in the War and his reaction to all English-speakers, including directors and playwrights, was, he’d thought, forever prejudiced. Now, he declared as we reeled aerated out into the Tokyo night, Shakespeare had finally brought us together.

Another time I helped an eleven-year-old boy play Juliet’s father Capulet in a workshop in a London comprehensive; as he uttered that terrible attack on his daughter for refusing to marry Paris, the boy suddenly grasped the pain not of being a misunderstood young lover (easy) but of being the middle-aged parent whom nobody seems to obey. I was also indirectly involved in organising a production of The Tempest in Maidstone high security prison, to be played by lifers who had never imagined Shakespeare to be a friend. They were visibly enfranchised by the physical sensation of speaking his language – not only by Caliban’s repeated cries of ‘Freedom… high day… freedom’ but by his ache to offer his talents to unworthy masters, in his case a drunken butler and a clown:

I’ll show thee the best springs; I’ll pluck thee berries;

I’ll fish for thee, and get thee wood enough…

I prithee, let me bring thee where crabs grow;

And I with my long nails will dig thee pig-nuts;

Show thee a jay’s nest and instruct thee how

To snare the nimble marmoset.

As he spoke, the actor – as the prisoner had become – craned for a view out of the hall’s high windows, even though it would only give him a vista of more prison cells. Caliban’s dream was to be able to live in the moment, moving faster and seeing more than anyone else; his interpreter’s was to take this one chance to join a different, forgiving world. No wonder the warders on duty were instinctively uneasy – this isn’t a freedom that can be taken away by the slam of a door.

Having thus been round the block with Shakespeare several times – pausing at Buckingham Palace and the British Academy and dodging the rats falling from the rafters in Mumbai – in my Fifth Age (and never mind the fair round belly) I’ve been touring a solo show, Sweet William. A sort of Golden Anniversary of that night with Macbeth at the Old Vic, it’s a many-coloured coat of prejudice, information and instinct, co-written by Shakespeare and myself. Like an earlier show I did on another great writer, Anton Chekhov, Sweet William approaches its elusive hero with due caution, palpable affection and even a sidelong sense of kinship – not as a writer of course, but as someone I have, after all, known all my life. Consequently the evening is not so much a daisy chain of Greatest Hits (it certainly doesn’t include the Seven Ages of Man) as biography tangled with autobiography, elaborated with performances of many unfamiliar pieces as well as some famous ones.

It may also feature in my Sixth and Seventh ages, so please watch this space. At the time of writing, Sweet William has played over a hundred performances – up and down Great Britain, in various London theatres (including the former home of Ben Travers’s Whitehall farces), in Romania, Hungary, Spain, Scandinavia and the US. The most common front-of-house poster design has a picture of myself with Shakespeare’s face behind me; he has deep rings under his eyes, as if tired of being talked about so much. Abroad I work sometimes with surtitles and sometimes with a simultaneous translator; both methods are extremely rewarding when they work, but they can be fraught with imprecision. You don’t want an audience, its eyes trained on the surtitles, laughing at the punchline of a joke before you’ve delivered it – or, conversely, after you’ve moved on to the next bit of narrative. Simultaneous translation involves a relationship of curious intimacy with the translator, as if you were being haunted by your own shadow, and often turns the auditorium into a kind of beehive, with two hundred pairs of headphones at full tilt. Both methods oblige you, for your collaborator’s sake, not to change anything or make any accidental cuts on the night: both require a slower pace of delivery, especially if, as sometimes, the foreign language is of its nature less swift than English. (Our monosyllabic ‘love’ translates into two syllables in Catalan, three in Hungarian and stretches to four in Swedish.) The challenge is to speak slowly but very interestingly – not so easy, especially when you hope to give the effect of spontaneity.

The intimacy of most (but not all) of the spaces chosen for Sweet William more or less guarantees an unusually friendly audience – why would they be there if they didn’t like Shakespeare and weren’t tolerant of me? Sometimes they return my greeting at the beginning of the show enthusiastically; sometimes they seem on the brink of answering back during it; sometimes they stay behind for a while at the end to chat about anything that’s intrigued them. The generations are – very agreeably – mixed. There was a woman not long ago who applauded when she sensed a cherished speech on its way, as if recognising the opening chords of a favourite song. She even murmured her way through one with me, each phrase a nanosecond ahead of me, which would have been difficult had it not been so charming. I felt I’d invented some new kind of entertainment akin to community singing.

Such experiences nicely demonstrate a point I make during the show. Shakespeare’s theatres held upwards of two thousand people, but since their stages were little bigger than what we would describe as studio spaces, his actors probably moved with ease from the grandly rhetorical to the televisually intimate. It’s not enough to say such a thing: I have to demonstrate it in my practice and prove that anything can be done in alternative ways. Depending on the venue, the heroic can become intimate and the confidential blossom. The Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis holds seven hundred; though I had always imagined my show in a more concentrated setting, the excerpts flowed naturally into every distant corner.

Two hours alone is an odd contest with yourself, like holding your breath for almost too long. Or spending a whole match having to keep possession of the ball and never passing it. And it’s lonely. It happens that the great Victorian actress Ellen Terry took her solo talk-and-performance Shakespeare show on the road when she was the same age as me – she had the same agent looking after her too, Curtis Brown. ‘Sixty-three one-night stands… it’s enough to kill a horse,’ she complained; and when she opened in Melbourne she was surprised to find, on coming out for her second half, that the audience had gone, imagining the evening done.

She also admitted that ‘Familiar faces are the only faces I understand… it takes so long to read the truth in new faces.’ It’s as good a description of homesickness as I know. It was in friendly Minneapolis, in seventeen degrees below, that the chronic solitude of the soloist bore down most on me. At the end of the evening I would go to the bar, logically enough, and hope – as much out of desire for company as vanity – that some member of the public would say hullo. Instead, as it eventually emptied, one or two would come over and hesitantly enthuse, politely saying that they hadn’t wanted to disturb me as I had my drink. Oh please, disturb me… Then I would return to the apartment and the washing up in the sink. This is not a plea for sympathy – as a boy I told my mother I could put up with the barmier aspects of the profession – just a bald fact that Ellen Terry would have understood.

I can’t help thinking Shakespeare would have enjoyed his status as international visa – he who never toured abroad – especially the steep contrasts. Dromio of Syracuse’s utterly non-PC account in The Comedy of Errors of being pursued by a woman so fat that he could imagine her as a globe played a little less comfortably in Colorado Springs than at home: only just tolerant of the obesity joke, the audience did however like him saying that, among the countries represented in her, America inclined deferentially to the ‘hot breath’ of Spain. Surprisingly, Chicago and New York didn’t pick up the Bush-ism of James I taking the credit for sniffing out the Gunpowder Plot (‘God has inspired me to foresee the conspiracy and root it out’), but Minneapolis did. My only regret about my US dates is that, to get the laugh, I have to turn myself into a fan of Manchester United rather than Tottenham Hotspur, the former being the only English football club everyone there knows, David Beckham having playing for Los Angeles. I imagined certain childhood heroes – Ron Reynolds, Ted Ditchburn and Alf Ramsey (and indeed my parents) – shocked by my expedient treachery.

I’m sometimes asked if Sweet William changes much from night to night, or week to week. Well, not much, any more than a play does, but it’s also true that over the months I’ve discarded and replaced, rephrased and rewritten a little, since around the existing script is a host of alternatives, probably enough to make up another show. Or, it has now occurred to me, a book. This volume has its roots in Sweet William, but is in no way the script. All the plays figure somewhere here, some of them briefly (especially if I’ve done whole books on them before), others at length when they particularly serve the story, with no special favours done to the more popular end of the canon. I’m more or less following the chronology of Shakespeare’s life – more or less: when particular themes present themselves, I double back or jump forward in time to pursue them. The narrative of Prince Hal and Falstaff, by some miracle, is both a great love story and a piercing anatomy of England, so it’s dealt with, unapologetically, at considerable length. In fact it is noticeable to me in general how often the Histories crop up: but then they account for about a quarter of the canon and are in some ways the heart of the matter.

The theatre rejoices in its transience, but you sometimes need to get an experience fixed. The published versions of Shakespeare’s plays that we depend on are a very different and much longer matter than what was actually performed, which was variable, sometimes depending on the weather and whatever was in the news that morning. The received wisdom is that he himself never felt the need to publish, but I’m not so sure – there is a suggestion that he cooperated a little in the preparation of the posthumously produced First Folio (blithely cutting some of his best stuff, including a major soliloquy from Hamlet). His Sonnets are obsessed with ‘devouring time’ and ‘sad mortality’; so if he did help, it may have been his effort to have the last word – to be, so to speak, definitive for the moment. In that respect, if none other, we may be alike.

1

The Rose of Youth

Sweet William – Poor Inches of Nature – William Page – Moth – Arthur – Marina – Perdita and Mamillius

Like distant conversation, we can hear his colleagues commenting on his pleasant nature, his industriousness, his ability to write so fluently that he hardly ever had to make a correction. This wasn’t an intellectual celebrity like Ben Jonson or a hellraiser like Kit Marlowe. One of his earliest editors, Nicholas Rowe, described William Shakespeare simply as

A good-natured man, of great sweetness in his manners, and a most agreeable companion

– while the antiquarian John Aubrey confirms that he was

a handsome, well-shaped man, very good company and of a very ready and pleasant smooth wit… not a company keeper… he would not be debauched, and if invited to, writ he was in pain…

Aubrey’s first, vivid phrase seems to bring Shakespeare quite close to us; the second suggests that this amiability was something he put on for politeness’s sake. And the intriguing final comment leaves it unclear whether his pain was of the moral kind or a tactical move on any particular night – like pleading writer’s cramp perhaps – to avoid offending his friends. Aubrey in any case was a notorious gossip, the kind that trusts his source at a remove or two: he can’t be quite sure of his facts but he has talked to a friend who is. And elsewhere he slightly undermines his own evidence by subscribing to the idea that the reason Shakespeare was friendly towards the children of the Davenant family, even giving them ‘a hundred kisses’, was because one of them was his own son by the wife. Or perhaps he was just a theatrical type who kissed everybody. Rowe is even less reliable, a scholar so absorbed in the novelty of editing the plays that he yearns to find the writer’s character behind them. And since both men were writing long after Shakespeare’s death in 1616 and didn’t know him – Aubrey having been born in 1626 and Rowe in 1674 – their point of vantage is hardly better than our own.

At a still greater distance, we too have our ideas about what William Shakespeare was like, or what we would like him to have been like. The continuing slew of biographies – some from specialist Shakespearians (but rarely practitioners), some from fiction writers, some from established biographers feeling they should at last turn to Shakespeare – keeps the urge half-satisfied. Some of the best – James Shapiro’s 1599 and Charles Nicholl’s The Lodger – go round to work, assembling their portrait by describing everything except Shakespeare himself: they look at the rooms he may have lived in, the streets he probably walked, the political circumstances in any particular month, and leave a Shakespeare-shaped hole in the middle. So we catch a glimpse, just a glimpse, of someone turning a corner ahead of us or standing at the top of the stairs, the whisk of his cloak as he hurries past, keeping close to the wall.

Sooner or later we demand, like Dickens’s Gradgrind, some incontrovertible facts. There aren’t many to be had, but not so few either. Shakespeare’s father was John, a glover, small businessman and by moonlight a moneylender; his mother was Mary Arden, from a Catholic family in the village of Wilmcote, just outside Stratford-upon-Avon. Mary had brought some money to the marriage, and just as well – John’s career was to be a chequered thing. Both parents signed their names with a mark, but that was not so unusual at the time; annoyingly for mythmakers, it doesn’t mean that Shakespeare’s loquacity was a compensation for illiterate parents.

William was Mary’s third pregnancy but her first child to survive; there were to be five more children, four of whom would reach adulthood. The house in which he was born, on a spring day in 1564, was on the north side of Stratford, where the Birmingham Road now begins, in Henley Street, opposite where the Food of Love Café currently stands, cheek by jowl with Mistress Quickly’s Tea Room and Iago’s Jewellers – the latter perhaps the most ominous yoking of ideas in the Bardolatry trade since the closure of Timon’s Restaurant. It seems that by local custom, a fortifying portion of something sweet – butter or honey – would have immediately been put on the tongue of the newborn Shakespeare, he who would so often be known as honey-tongued.

The entire structure tumbles to the ground if you elect to believe, as some do, that Mary Arden returned for her confinement to her family house in Wilmcote: if so, the whole Shakespeare industry should be mentally transported five miles along the road with her. And it is obliterated completely if you incline to the view that the Man from Stratford was not the author of the plays at all, but a front man who deprived the suddenly modest Earl of Oxford, or Francis Bacon, or Christopher Marlowe, or Queen Elizabeth, or Sir Walter Ralegh, or Robert Cecil, or the Earl of Southampton, or Amelia Lanier (also a candidate for the Dark Lady of the Sonnets), or Sir Philip Sidney, or James I of due credit for breaking off their own careers to write thirty-seven superior plays anonymously. I don’t plan to deal with that controversy any further in this book because it bores me, not least because it seems unlikely that when Ben Jonson described Shakespeare as the Swan of Avon he didn’t mean that his friend lived in Stratford; or that Oxford contrived to write King Lear after his own death. The current answer to the latter problem is that the play must have been revised by various hands after Oxford died to make it worthy of performance, because otherwise it couldn’t have been written by Oxford. The splendid circularity of this reasoning is of a piece with the snobbish idea that a Warwickshire grammar school boy was less qualified to write Julius Caesar than a university-trained aristocrat.

If you venture to accept the authorised version of events, then a few days after his birth, on April 23rd or so, Shakespeare’s father would have taken the future author of Hamlet in his arms and, accompanied by the godparents, or ‘gossips’, carried him along Henley Street to the Market Cross, then right along the High Street, perhaps left down Sheep Street to the open fields that ran down to the river; then right, past the site of the future Royal Shakespeare Theatre, to Holy Trinity Church for his baptism service. Amazingly to us, his mother didn’t attend the ceremony. The author of the Book of Leviticus suggests to the children of Israel that mothers are still impure in the aftermath of childbirth; the idea was taken up by the Christian Church, though by the sixteenth century there was a kinder explanation for the exclusion: Mary would have waited at home for forty days before being ‘churched’ because there was a danger of being taken by the fairies otherwise. Then she would be welcomed back into the community with thanksgiving for her survival. Shakespeare meanwhile would have been dressed for the occasion in a little white linen robe anointed with oil and balsam; this was the chrisom cloth, and it had a secondary use – if a baby died within a month of birth the garment could be reused as a burial shroud. This was much to the point in Stratford that year: as the summer warmed up, plague would carry off nearly 250 of the town’s 1,500 citizens, and only one baby in three would survive. So the new arrival must have been a reasonably tough nut.

Poor inch of nature,

Thou art as rudely welcome to the world

As ever princess’ babe…

– Pericles

The mature dramatist didn’t have much to say about coddling, swaddling or infancy in general. It’s as if he couldn’t wait to get his youngsters away from their apron strings – though he clearly enjoyed the idea of the teenage Juliet having to listen to her Nurse reminisce about sitting under the dovehouse wall and suckling her, minutes before she meets her sexual destiny in Romeo and becomes a tragic heroine. His other significant nursing is corrupted: Lady Macbeth intriguingly refers to a childbirth in her past, but swears she would have torn the child from her breast if she’d thought Macbeth would break his promise to murder Duncan.

Having survived the Plague Year, Shakespeare’s own early childhood seems to have been happy enough in the pleasant honey-coloured house in Henley Street – probably much as it is now, except that in its wild garden the foul smells of skins being tanned by his father for gloves would have mingled, in a steep Shakespearian contrast, with the

Hot lavender, mints, savory, marjoram,

The marigold, that goes to bed with the sun

And with him rises weeping.

However, his own stability contrasts with the condition of his imaginary children, who generally have a rough time, the more so for their customary intelligence. The first to utter is probably Lucius in Titus Andronicus: his job in the play is to cheer up his grandfather Titus, who has recently cut off his own hand, and to look after his aunt Lavinia, who has just been raped and had both hands cut off and her tongue cut out:

TITUS: This poor right hand of mine

Is left to tyrannise upon my breast…

Then thus I thump it down…

[ToLAVINIA.] Thou shalt not sigh, nor hold thy stumps to heaven…

LUCIUS: Good grandsire, leave these bitter deep laments: Make my aunt merry with some pleasing tale…

TITUS: Peace, tender sapling, thou art made of tears…

If this is the sort of talk Lucius has to put up with from his grandfather it might have been better if he rather than Lavinia had lost his tongue. The miserable little group go off at the end of the scene to the edifying prospect of Titus reading

Sad stories chanced in the time of old

– with the warning that the boy will have to take up the narrative when Titus’s eyes get tired.

Then there are the little Princes in Richard III, who end up in the Tower of London with a cushion over their faces; but on the evidence of what we see of them –

I want more uncles here to welcome me…

Fie, what a slug is Hastings

– I find them so obnoxious that I’m almost as glad as Richard to see the back of them. These are the kind of Shakespearian kids that turn you into Miss Trunchbull from Roald Dahl’s Matilda. Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing is given a Boy who contributes only one irritating turn of phrase, like a tiresome teenager:

BENEDICK: Boy –

BOY: Signor?

BENEDICK: In my chamber-window lies a book; bring it hither to me in the orchard.

BOY: I am here already, sir.

BENEDICK: I know that; but I would have thee hence, and here again.

However, this part and moment were redeemed forever in John Barton’s 1976 Royal Shakespeare Company production of the play set in the Raj, when the Boy became an infinitely patient Indian servant (Paul Whitworth) who, knowing his master’s liking for an afternoon read in his hammock, already had the book ready in his hand. So ‘I am here already, sir’ became ‘I have anticipated your every wish’. Not troubling to look at him, Donald Sinden’s Benedick irritably dispatched him as if he were an idiot. Rather than embarrassing his master, the servant gently walked to the back of the stage and after a moment returned to present the book.

Young John Talbot in Henry VI Part One has loyally become a soldier at the side of his bellicose father, also called John: so he can never escape his shadow, and they die together on the battlefield. In Macbeth, a play no child should find himself in, Lady Macduff’s son is appealing because of his superb defiance of the murderer sent to dispose of him:

Thou liest, thou shag-eared villain…

He has killed me, mother: run away, I pray you!

Myself, I blame the parents, or at least the fathers. Talbot might have considered a safer profession for his son; Macduff perhaps shouldn’t have run away to England, leaving his family behind him.

Such children, doomed by adult ambition or narcissism, are caught up in stories too big for them: they are there more or less for an instant effect, pathos usually. However, there are others who are present for a more substantial reason. Lucius in Julius Caesar makes a single pluck on the heartstrings because he falls asleep while playing a tune to his master Brutus. He then slumbers through the appearance of Caesar’s Ghost in the tent: it’s an affecting thing to see the dictator of the known world, the doomed revolutionary and the oblivious boy all there together in the same frame. Lucius may also be a means of pointing up how much better Brutus treats his servant than he does his wife. Having just reported the death of Portia, more or less killed, we feel, by his neglect, he now reproaches himself for being too preoccupied to notice Lucius’s tiredness:

If thou dost nod, thou break’st thy instrument;

I’ll take it from thee, and good boy, goodnight.

However, a few become masters of their destiny, or at least of their immediate future, such as the schoolboy William Page, who appears briefly in Shakespeare’s only play about the contemporary middle class, The Merry Wives of Windsor, where his job is to show up his elders’ lack of imagination. For Windsor we might read Stratford. At about five, William Shakespeare would, willingly or unwillingly, have gone for a couple of years to his elementary (‘petty’) school, and then trudged along the High Street to King Edward VI’s new grammar school at the top of Chapel Lane. There he joined a class of about forty boys, all studying a full twelve hours a day with a small break for bread and beer, six days a week, no long holidays. He learned how to turn prose into verse – a gift that would stand him in spectacular stead later when he borrowed Plutarch’s description of Cleopatra’s barge from Thomas North’s translation:

The poop whereof was of gold, the sails of purple and the oars of silver which kept stroke in rowing… there ran such multitudes of people one after another to see her that Antonius was left post alone in the market place.

He gave this wings simply by adjusting the phrasing to make it metrical and adding a breath of genius here and there – the winds become ‘lovesick’ because of the perfume of the sails and the solitary Antony sits ‘whistling to th’ air’. And as for Cleopatra’s own person:

It beggar’d all description; she did lie

In her pavilion – cloth of gold, of tissue –

O’er-picturing that Venus where we see

The fancy outwork nature.

He also studied the art of rhetoric – the matter of taking an argument and making both sides convincing – which would come in handy for young Prince Arthur in King John as well as other debates that still keep audiences on the edge of their seats. Since Latin was all the rage among parents of every class, he duly learned how to translate it into English and back – an unremarkable achievement for children of the time that has misled some into believing that only a university man could have written the plays. Shakespeare wore his Latin as lightly as one now might elementary French: he inevitably knew a great deal of it, perhaps as much as a university graduate today. Ben Jonson’s comment that he had little Latin and less Greek would have been more aptly applied to his forever shaky history and geography.

A recent RSC production of The Merry Wives attracted the wrath of one critic, outraged that the ‘integral’ scene of the Latin lesson endured by William Page had been cut, rather as if To Be or Not to Be had been excised from Hamlet – a speech which, come to think of it, doesn’t contribute much to the plot either. The fact is nothing could be less integral than the episode in which Sir Hugh Evans examines his young pupil: its real interest lies elsewhere. As commentators are fond of pointing out, Thomas Jenkins, Shakespeare’s Latin teacher at King Edward’s, was a Welshman like Sir Hugh, whose student, by happy chance, is called William. This, by the way, is not the only appearance of William in the works of William; in Henry IV Part Two he seems to have survived school so successfully that he’s about to graduate from university:

SHALLOW: I dare say my cousin William is become a good scholar? He is at Oxford still, is he not?

SILENCE: Indeed, sir, to my cost.

SHALLOW: He must then to the Inns of Court shortly…

William then transmogrifies into a lovelorn shepherd in As You Like It, who has been ‘born i’ the forest’ but who also describes himself as ‘not learned’ – which is in a way true of Shakespeare, who was born near the Forest of Arden and whose intelligence was not academic. These three plays were written within three years, so this was obviously a running gag offered by the playwright to his loyal audience.

In The Merry Wives it’s a day off school, presumably a Sunday, but William is to have extra tutoring at his father’s behest – no doubt this is the reason he has to be encouraged to ‘hold up your head; answer your master’. His main task is to be the declension of the Latin word for ‘this’ – ‘hic haec hoc’ – which allows Shakespeare an accent joke:

EVANS: What is your accusative case?

WILLIAM: Accusativo, hinc.

EVANS: I pray you, have your remembrance, child, accusativo, hung, hang, hog.

The right answer is ‘hunc (hanc/hoc)’, so Hugh seems to have developed a sudden nasal congestion not particularly typical of a Welshman. It’s also hard to see how a Latin teacher could follow a nice phrase about remembrance with a perfectly rendered Italian word, only then to make his Latin incomprehensible; but with a joke in hand, Shakespeare will sacrifice anything, especially if he can involve a regional or a foreigner (there is a funny Frenchman in the play as well). Or if he can make fun of the ill-educated – Hugh’s mistake lets in Mistress Quickly for a clumping joke:

Hang-hog is Latin for bacon, I warrant you.

In the same vein, she then mistakes the Latin word ‘caret’ for the vegetable. And if there can be a hint of what Shakespeare’s editors would call impropriety, so much the better; for good measure Mistress Quickly turns in a couple of double entendres when Evans asks William for some declension:

EVANS: What is your genitive case plural, William?

WILLIAM: Genitive case?

EVANS: Ay.

WILLIAM: Genitivo – horum, harum, horum.

This time it’s the right answer, but there may have been a snigger both in William’s reaction to ‘horum’ and in ‘genitive’ being linked with ‘case’, since, in case you hadn’t guessed, ‘case’ was a slang word for vagina. It is certainly a gift for Mistress Quickly:

MISTRESS QUICKLY: Vengeance of Jenny’s case; fie on her! Never name her, child, if she be a whore.

EVANS: For shame, ’oman.

MISTRESS QUICKLY: You do ill to teach the child such words…

EVANS: ’Oman, art thou lunatics? Hast thou no understandings for thy cases and the numbers and the genders?

Oh dear. It would be a pleasure to meet William Shakespeare in heaven, but I’d have a couple of bones to pick with him. This is the man Voltaire said showed ‘not the least glimmer of good taste’, the friend of whom Ben Jonson sorrowfully reported:

His wit was in his own power; would the rule of it had been so too.

However, behind the scene’s seaside-postcard humour lurks an important Shakespearian idea: that language is for those whose imagination is still free, who can hear the sudden music of one word meeting another, rather than for the totalitarian Malvolios and Hugh Evanses who would order and control it:

EVANS: What is lapis, William?

WILLIAM: A stone.

EVANS: And what is a stone, William?

WILLIAM: A pebble.

EVANS: No, it is lapis; I pray you remember in your prain.

Aching on the wooden bench of King Edward’s and looking forward to the beer-break, any pupil might take refuge in his imagination: he might well, like Edgar in King Lear, see a stone not just as a stone but as part of the ‘unnumber’d idle pebble’ on Dover beach chafed by the ‘murmuring surge’, or as a thing thrown off ‘the raging rocks and shivering shocks’ invoked by Bottom. However, from Hugh Evans’s point of view language is not to do with such fripperies: it is only the vehicle for translating Latin into English and back again. He would presumably approve of a contemporary manual of pedagogical practice that instructed the pupil to

Take the horn book in thy hand: stand upright. Hold thy cap under thy arm. Hearken attentively how I shall name these letters. Mark diligently how I move my mouth. See that you rehearse them so…

In other words, there is only one right way. When we irritably watch mouths categorically moving on Prime Minister’s Question Time; or vainly attempt a phone conversation with an internet provider; or shudder at being encouraged to have a nice day by a complete stranger; or, within the arts, rebel against our paymasters’ talk of meeting the diversity challenge through clusters and cohorts and walking the walk, we are inheriting Shakespeare’s fight to stop language being wickedly drained of meaning.

A most acute juvenal, voluble and free of grace…

– Love’s Labour’s Lost

It is always a mistake to vex a budding writer, and Shakespeare felt enough resentment towards his teachers to go on taking small revenges. His next mockable pedagogue is Holofernes in Love’s Labour’s Lost. This is a man who, as well as baffling everyone with Latin quibbles, is not impartial to a little bit of caning and takes a kindly custodial interest in the country wench Jaquenetta. In another part of the play his natural antagonist, the child Moth, is in fact page to the ‘fantastical Spaniard’ Don Armado (since the Armada the Spanish were good for a laugh). Moth is described by Costard the clown as ‘not so long by the head as honorificabilitudinitatibus’ (a word perhaps learned from Holofernes, but, more alarmingly, an anagram of a claim supposedly made in Latin by Francis Bacon that he had written the plays); but he is very long in terms of lines, the most substantial part for a child in Shakespeare. Moth has an answer for everything, sometimes a hoary old Shakespearian joke –

ARMADO: Who was Samson’s love, my dear Moth?

MOTH: A woman, master

– and sometimes a gentle antithesis:

ARMADO: How hast thou purchased this experience?

MOTH: By my penny of observation.

His ability to run rings round everybody he meets draws a not altogether affectionate tribute from his master, a man himself not free of linguistic vanity, who may sometimes wonder about his wisdom in taking on a page so very ready to upstage him. In the end, Moth is humorously cast as Hercules in a performance of The Nine Worthies put on for the royal lovers, only to be uncharacteristically ‘put out of [his] part’ by not being listened to by the women in the audience. Rather to our satisfaction, even Moth is thus defeated by the play’s verbal profligacy, a great feast of language from which even he (as he says of Armado and Holofernes) could only steal the scraps.

It’s tempting to imagine that Prince Arthur in King John might originally have been played by the same bright young actor who undertook Moth. It is hard to find a good enough boy to play either of them in our less linguistic times, but Shakespeare’s company must have included young virtuosi for whom he could safely have written such parts, let alone the women they also performed. Arthur is Moth’s natural cousin, but cast in a tragic light; he is still one of the major attractions of a play which, much more popular with the Victorians than it is with us, has the distinction of being the first known Shakespeare film: sections of Herbert Beerbohm Tree’s 1899 stage production were shot, and a small fragment survives. Ellen Terry played Arthur for him at the age of nine (apparently in a pair of baggy pink tights and a little silver dress): presumably her evident girlhood made the story still more pitiful. In retrospect she would have been pleased to have done it: she later used to point out rather tartly – ignoring Coriolanus – that it’s all fathers and daughters in Shakespeare, and Constance and Arthur are at least mother and son. The infant phenomenon was much loved for the performance, except by one German visitor, the novelist Theodor Fontane, who tellingly thought her ‘intolerable… a precocious child brought up in the English manner, old before her years’.

Our problem these days with John is that its main interest lies away from the play’s title role. Although the historical John was an exceptionally bad King, Shakespeare’s denigration of him at the time would have had some shock value, as he was sometimes seen by Protestants as a semi-heroic figure for defying Rome like Henry VIII. Having tilted the scales in this way, Shakespeare, who may have been guarding his own Catholicism, then tilted them back again not only by omitting any reference to the humiliation of the Magna Carta, but by presenting the Papal legate Pandulph as a ‘meddling priest’, extravagantly ruthless, quibbling and devious. His King John is a listless casuist and manipulator, though he does get a superb death scene, poisoned in the orchard of Swinstead Abbey by a monk who is then so overcome with guilt that ‘his bowels burst out’.

With Richard III in hand at the time and Macbeth ahead of him, some of the operating techniques of a man such as John do interest Shakespeare. All three are expert in the dropping of hints – Macbeth’s briefing of the murderers of Banquo will be the best example, but John gets a fine Stalinist moment when, without explicitly going on the record, he conveys to Hubert that young Arthur, his nephew and rival to the throne, should be removed:

I had a thing to say,

But I will fit it with some better time…

I had a thing to say, but let it go…

The clinching moment of this produces the most striking (and ostentatious) manipulation of a single verse line Shakespeare has yet achieved, a command issued to his actors to pick up their cues sharply:

JOHN: Death.

HUBERT: My lord?

JOHN: A grave.

HUBERT: He shall not live.

JOHN: Enough.

I could be merry now…

In general, however, the victims of John’s schemes are more engrossing than he is. In particular, his nephew Arthur is a diminutive source of big trouble. Arthur’s mother Constance, an early study in the type of maternal dragonhood that Shakespeare would perfect in due course, is determined that he shall be King, despite the fact that the previous monarch, Richard I, has nominated his brother John to the job, as he was entitled to do. She behaves like the worst kind of show-business mother enraged that her boy isn’t getting cast: throwing herself on the ground in front of the Kings of France and England, she wails and excoriates, to the embarrassment of Arthur, who is deeply uninterested in the matter:

I am not worth this coil that’s made for me…

She also laments at great length the special, though not unusual, misery of widowhood; and as for the driving love she feels for Arthur, she makes it clear that it is fortunate that the boy is ‘fair’ since she wouldn’t love him if he wasn’t.

The intemperate emotions of this mad world eventually wash over Arthur and drown him; but he struggles astutely, with some of the skills Shakespeare would have learned at King Edward’s School. We perhaps see the boy now through sharper eyes than the Victorians did: Shakespeare’s cunning lies in making him impossibly modest and lovable while giving him the instincts of a first-class advocate. Captured by his wicked uncle, he falls into the hands of Hubert de Burgh, historically a powerful landowner who pressured the King to sign the Magna Carta, but in the play a man who arrives from nowhere. Shakespeare, untroubled by history, simply borrows the name and defines him only by his grim task as Arthur’s jailer and, John hopes, his executioner.

Mortal fear makes Arthur undertake some truly complex negotiations. For reasons that can only have been to crank up the horror, John has decided to have the boy blinded rather than simply cutting his throat. Arriving in the cell with a brazier and hot irons, Hubert is at first so implacable that even the executioner accompanying him recoils from the work, only to be reproached for his ‘uncleanly scruples’. However, Hubert is to meet his match: the boy is smart in a Shakespearian way:

Is it my fault that I was Geoffrey’s son?

To make matters worse, he seems to have some unfathomable personal affection for Hubert:

I would to heaven

I were your son, so you would love me, Hubert…

Are you sick, Hubert? You look pale today.

In sooth, I would you were a little sick,

That I might sit all night and watch with you.

I warrant I love you more than you do me.

When the realisation of his fate comes, his love, turned to shock, shames his keeper:

Have you the heart? When your head did but ache,

I knit my handkercher about your brows…

And with my hand at midnight held your head;

And like the watchful minutes to the hour

Still and anon cheer’d up the heavy time,

Saying, ‘What lack you?’ and ‘Where lies your grief?’

This unlikely account of Arthur’s captivity certainly raises the sentimental ante. We may also notice that his tender sagacity is touched by an effortless snobbery: he points out en passant that as a Prince his love is worth more than that of ‘many a poor man’s son’.