Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Biteback Publishing

- Kategorie: Fachliteratur

- Sprache: Englisch

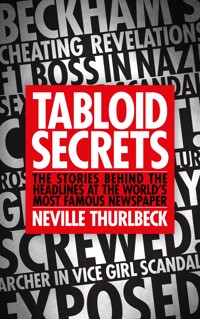

In nearly twenty years at the top of the News of the World, Neville Thurlbeck - chief reporter, news editor and scoop-hunter extraordinaire - served up some of the most famous, memorable and astonishing headlines in the paper's existence. They lit up the world of tabloid journalism and featured names such as David Beckham, Fred and Rose West, Jeffrey Archer and Robin Cook, among many others. Along the way, Thurlbeck was drawn into encounters with Cabinet ministers, rent boys, sports stars, serial killers, drug lords and, on one occasion, a devil-worshipping police officer. He worked with MI5 and the National Criminal Intelligence Service, foiled a murder and gave Gordon Brown a tongue-lashing to remember, all in the name of journalism. Now, in Tabloid Secrets, he reveals for the first time the truth about how he broke the stories that thrilled, excited and shocked the nation, and secured the paper up to fifteen million readers every week. The result is a fascinating, scandalous, swashbuckling insight into some of the biggest and most sensational scoops by Fleet Street's most notorious reporter.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 388

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TABLOID SECRETS

THE STORIES BEHIND THE HEADLINES AT THE WORLD’S MOST FAMOUS NEWSPAPER

NEVILLE THURLBECK

To my wife, Boo and Bee, my family and special chums, and Ralphie, my Border terrier.

For your love and laughter.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

IN PENNING THIS little memoir, I have tried to give a flavour of what life was like working for Fleet Street tabloids during the 1980s, ’90s and up to the closure of the News of the World in 2011.

Since then, there has a been whole sea change in the way the tabloids report their news and the types of stories they cover. The Leveson Inquiry, numerous police investigations and a torrent of criticism (to put it mildly) from outraged celebrities and politicians have seen to that, for better or for worse.

But for a quarter of a century, I helped the red-top newspapers dole out their daily fare of scandals and exposés with cavalier abandon. And the British public bought into it in their millions.

It is a world that has vanished for good. And it is an insight into this very bizarre career which I thought you might be interested in seeing, through the eyes of a man who spent his life there. I hope you find it an entertaining read.

If none of you read it, it will at least provide future generations of my family with a lasting monument to the absurd and bonkers world of their bizarre ancestor!

Those of you looking for an insight into the phone-hacking saga will be disappointed. I think most of you will now be fed up to the back teeth with the wall-to-wall coverage of it over the past several years. And I don’t want this book to be boring, self-serving guff. And I have no wish to heap piles of blame on anyone, many of whom are suffering greatly as I write. Finally, to focus on phone-hacking would distort the narrative, as it came onto my radar less than a handful of times in twenty-five years. That it came onto my radar at all is, of course, extremely regrettable and I apologise to anyone affected by it.

You will also hear very little of my wife and children, as I don’t want them to become part of this story, although they are a large part of my ‘normal’ life.

While I covered hundreds of stories for the News of the World, the Today newspaper and the Daily Mirror, I have picked out a dozen or so which I hope give a flavour of how we worked in those ruthless, cut-throat times.

For a young man, they were an adventure. One minute, you could find yourself in the middle of an Alfred Hitchcock thriller. Next, a Marx Brothers comedy. Another, a Jacobean tragedy. It was never dull and I hope this book is a fair reflection of the industry I now look back on with fondness and astonishment.

CHAPTER 1

THE EARLY YEARS

THE EXPRESSION ‘GENTEEL poverty’ could have been invented to describe my family. I was born in the front bedroom of 33 Merle Terrace, Sunderland, in what was then Co. Durham, on 7 October 1961.

It was just after breakfast, so as the midwife held me up to slap my bottom, my first view from the Victorian sash window would have been of thousands of men marching to work in the shipyards. Their tightly belted raincoats, flat caps and old gas mask haversacks slung over their shoulders carrying their lunchtime ‘bait’ was a daily sight in that town, which prided itself on its heavy industrial heritage. Some of the older men still wore hobnailed boots, striking the occasional spark which played on the cobbles at dusk.

We lived on the main road, which was just a five-minute walk downhill to the world-famous Doxford shipyard. Together with Laing’s, Thompson’s, Clarke’s, Short’s, Austin’s, Bartram’s and the Corporation Yard, they produced a quarter of the nation’s shipping during the Second World War, an impressive 1.5 million tons. Sunderland was by then the biggest shipbuilding town in the world, and ships and engineering were fixed in my family’s DNA.

My maternal grandfather, Jack Tunstall, worked at Doxford’s as an engineer. On my father’s side, the Thurl family had arrived as Viking invaders and established a settlement near the source of the river Wear. Bekkr is Old Norse for stream or brook and the name gradually morphed into Thurlbeck. And there we remained for the best part of a millennium.

For most of the nineteenth century and into the early twentieth, the Thurlbecks were river pilots. Their task was to board large ships coming into port and carefully navigate them around the dangerous sandbanks at the mouth of the river Wear, and the jobs were passed from fathers to sons.

The landscape and lifestyle into which I was born will seem to some like another world but was the norm in post-war northern England. We had an outside lavatory, no telephone and no car. And we never went ‘abroad’. In my family, anywhere outside England was simply classed as ‘abroad’. It was dismissed as a place of no consequence – ‘Why would we want to go abroad for?’ So our holidays were taken in Devon, the Lake District or at my aunt and uncle’s home in the Buckinghamshire countryside. And for something a little more exotic, Wales or Scotland, with my mother cheering, ‘Look, we’re crossing the border now!’ as we all clapped and wondered at the sheer vastness of our journey in our 1960 Ford Classic.

The holidays at my aunt Margaret and uncle Warren’s in the 1960s and early ’70s were idyllic and provide me today with my happiest childhood memories. I am still incredibly close to them. At their little cottage in a peaceful, pretty little village, I had my first glimpse of another type of England, completely different to the one I’d been brought up in. Fields of barley sprouted from pleasingly rounded and evenly eroded hillocks of chalk. The average Buckinghamshire man and woman still spoke with a distinctive, slightly West Country burr, now long since vanished. And the elongated summers seemed to turn everyone an attractive light tan, rather than the sallow hue of the average Wearsider, who lived beneath slate-grey skies.

My uncle Warren was and still is full of mischievous, schoolboy charm; my aunt Margaret – my mother’s cousin – one of the most enchanting and elegant ladies I’ve ever met. To be with them was huge fun. And, together with my parents, I saw the picture-postcard Bucks countryside with its church-steepled villages. There were trips along the Thames on riverboats, Disraeli’s house at Hughenden, biplanes at Old Warden aerodrome and a fabulous toy shop in Old Beaconsfield, where I once saw the actress Dame Margaret Rutherford in 1969, giving me my first glimpse of a celebrity.

There would be day trips to London, too. There were two highly exotic areas of London that really captured my imagination. Shaftesbury Avenue with its theatres cheek by jowl and the names of the great and the good up in lights – Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud in No Man’s Land, Donald Sinden and Frank Thornton in Shut Your Eyes and Think of England and John Quayle and Penelope Keith in Donkeys’ Years. This was my first taste of proper theatre. I’d scour the listings pages of the Sunday Times to see if I could spot anyone famous appearing in the West End and off we’d all go, via the Tube from Amersham, to the Globe or Wyndham’s. From the age of around ten, I was mesmerised by the magical world beyond the proscenium arch, and the passion has never left me.

The second area of intrigue to me was Fleet Street. In 1968, it was the epicentre of the biggest and best newspaper operation in the world. I recall being taken aback that the newspaper offices were all so close together, and have a vivid memory of my uncle taking us there, simply to look at the buildings. During one of our London visits, he paid the taxi driver five shillings as we stepped out in front of the Daily Express’s art deco office just a few seconds’ walk from the Daily Telegraph, resplendent with its masthead, which conveyed gravitas and importance. Around the corner, in Bouverie Street, the jaunty, almost Wild West-style lettering of the News of the World masthead lay at the other end of the spectrum.

It would be inaccurate to say I felt that my future lay here. But I do remember being deeply impressed with this little village’s power to communicate. It seemed incredible to my young mind that in this street, men and women clattered away on typewriters. And by some miracle, the following day this somehow materialised into a newspaper put through a letterbox in Sunderland. I had the sense that Fleet Street really mattered. That it did something utterly fascinating and worthwhile. But that it was all very unfair for it to be based entirely in this street, 300 miles away. A hopeless aspiration. But a lasting impression had been made.

As well as creating a lifetime of love and affection for my aunt and uncle, these holidays opened my young eyes to possibilities further afield than Sunderland. From the age of ten, I knew that when I left home, it would be for ‘the south’.

Apart from my grandfather Tunstall’s brothers John and William, who were killed on the Western Front in 1915 and 1917 aged seventeen and nineteen, and my mother Audrey’s weekend coach trip to Paris with a girlfriend in 1955, I was the first member of the family in living memory to set foot on foreign soil, in 1981, when I was nineteen.

After setting up their Viking camp on the Wear, the Thurlbecks had remained resolutely intimidated by the notion of travel ever since. In fact, my father’s father, the identically named Thomas Edward, often repeated a story of how, as a young man in the 1920s depression, he was forced to take a job as a train guard. After falling asleep in the guard’s van on a train from Sunderland to Middlesbrough, where he was due to get off, he eventually woke up at Doncaster.

I only have two memories of my grandfather Thurlbeck. My first was Christmas and he’d bought me a small train set. As we played with it on the floor of his home, he pointed to the guard’s van and said he used to sit in one like it as a young man. He added: ‘I went to Doncaster once, you know.’ Even at five years old, I remember being distinctly underwhelmed by this achievement. My second and last memory of this quiet, modest, moderate man was being taken to see him as he lay on his deathbed a few months later as lung cancer ravaged his once athletic frame. In his youth, he had been a brilliant footballer who was awarded a contract with Charlton Athletic in the 1920s, only for my grandmother to ban him from moving away from Sunderland. (She probably thought it was ‘abroad’.)

The sight of my grandfather sipping water from a light-blue plastic cup covered with a lid so he could hold it without spilling, and my father’s obvious distress, still pains me. A few weeks later he was mercifully dead.

As an out-of-work engineer in the early 1930s, he was so hard up my father didn’t have a single toy to play with and had to improvise by playing toy motor cars with his dad’s shoes. My father told that story to me once in one of his ‘you don’t know how lucky you are’ moments. I laughed so hard he never told it again.

Our first home was an old, end-of-terrace house, heated only by a coal fire. Condensation froze on the inside of the windows, creating fascinating snowflake patterns. This, along with the dark, mysterious air-raid shelter in the back yard, where my father kept his paint tins, and being scooped up by my panicking mother as I tried to crawl down a steep flight of stairs, are my only memories of 33 Merle Terrace.

I realise this may seem like abject poverty to some now, but in 1960s Sunderland, it was very much the norm. The ’60s never swung in Sunderland. I remember the ‘summer of love’ in 1967, seeing the long-haired hippies strumming guitars on Seaburn beach. Except the ‘hippies’ were muscular, with tattoos and the telltale blue-black scars on their backs and arms where coal dust had lodged in cuts as they crawled along narrow seams down the mines. Even to my young eyes, the incongruity struck me.

There was very little sign of the great cultural liberation sweeping the country. If the strains of the Beatles or Rolling Stones could be heard, it would be from an old valve wireless inside one of the thousands of humble workers’ cottages. Maybe wafting through a scullery window and into the cobbled back lane where baggy-trousered youths kicked bald tennis balls against a wall, scoring a goal every time they hit the small wooden coal hatch. Everywhere was steeped in the grimy modesty of heavy industry.

As well as the scarred backs, there were other ways of spotting a coal miner in ‘civvies’. In the outlying pit villages, the older men who had hewn coal for forty years would crouch down on their haunches as they drank their beer outside pubs or chatted in the park. These unique circular, hunched gatherings were a legacy of a lifetime spent working three-foot seams. Their clothes were famously gaudy too, the odd dash of yellow here or orange there to compensate for a life in darkness. And many had a passion for pigeon fancying or leek growing. Above the soil, miners craved colour and serenity.

They were tough men, too. One of the toughest boys I knew played centre forward for a local team, Roker Boys, which acted as a feeder team for Sunderland AFC. As a midfielder, I played alongside him and watched with admiration his strength and physical prowess and how he dominated the field, a man among boys.

A couple of years later I bumped into him in one of the town’s pubs. He’d gone down the pit and, although muscular and robust, looked a shadow of his former self. His cheeks were sallow and sunken, his back slightly bent and he was already coughing badly through the coal dust. He was twenty but looked forty. I asked him how he was and how the job was going. My old friend, who had proved so fearless when boots and elbows were flying around on the football pitch, was frank and honest. ‘Everyone thinks we go down there in white overalls these days. I’m working a two-foot six-inch seam in three inches of water and it’s f****** awful!’

The left can say what they like about Thatcher closing the pits. I never met a miner who wanted his son to follow him to the pithead.

My father, Tom, was a part of this industrial landscape. He was head of what is now called human resources but was then known as personnel management, working for Bristol Siddeley Engines, Rolls-Royce and David Brown, who made the gears for tractors as well as the Aston Martin. He ended up as the north-west regional director for Community Task Force, a part of the old government Manpower Services Commission.

Thanks to my father’s professional progress and my mother Audrey’s long hours as a nurse and later a social worker, we ended up moving to an upmarket part of town in Barnes and later to a large Victorian house in Ashbrooke, considered the nicest part of town.

I started the chapter with the notion of the 1960s being one of ‘genteel poverty’ for my family. The poverty, or at least the relative poverty by today’s standards, contrasted sharply with another part of the family history.

My mother’s family had lived on the south banks of the Wear for generations. My maternal great-grandmother, Margaret Graham, was a formidable businesswoman. By the 1910s she had amassed a property fortune consisting of a whole street of houses in one part of Sunderland and half a street of houses in another. She also owned a chain of grocery stores.

They had enough money to give all their numerous sons, daughters and grandchildren smart houses for wedding presents. And my great-grandfather retired to the life of a gentleman aged just forty.

However, death duties and their largesse, coupled with the chronic asthma that plagued my family and made several bedridden and dependent, meant the fortune slowly dwindled. By 1949, the Attlee Labour government had taxed a lot of hardworking entrepreneurs out of existence with a top-rate band of an eye-watering 98 per cent. This meant for every pound they earned, they were allowed to keep the princely sum of 3d (2p).

By 1961, when I came along, this vast fortune had dwindled significantly. My parents were provided a home by my grandparents, but it was the humble terraced home in the shadow of the shipyard crane jibs.

I frequently joke that when anyone dies, I get the old watch. I’ve no idea where the cash goes to! The last relatively wealthy Graham to go west was my dear old aunt Edna, who died childless and left her entire estate to an osteoarthritis society. The only thing I managed to retrieve among the old family heirlooms and artefacts was my great-uncle’s First World War medals. And then I had to technically steal them from the house before the charity got their hands on them and auctioned them off for buttons.

Great-grandmother Graham was a magnificent northern matriarch by all accounts. She died from heart failure aged sixty-four in 1934. A symptom of her illness in the last stages was apparently a bloated appearance due to extreme water retention. This caused my grandmother, her daughter, to describe her fatal illness to me as a boy as ‘drowning in her own waters’, which I thought sounded intriguingly horrific. Why ‘waters’ had to be plural, I still have no idea.

Not many people are remembered three generations down the line. But my great-grandmother is still spoken of with reverence even by the fourth. Flowers are still placed on the family grave in Sunderland even though she has been dead eighty years.

I was educated in the local state schools and formed many very happy friendships there that endure to this day. My secondary education was at the same school as my father – Bede School. This was an old-style grammar school turned comprehensive. Some teachers still wore gowns, the cane was liberally used and it had the best reputation in the town, if not the county. Gradually, its status was eroded by the conversion to a comprehensive school. And in the 1990s, the narrow-minded socialist council that has blighted Sunderland’s growth and improvement for generations turned it into a sixth-form college. I later learned from a council member that this was because many of the Labour councillors who had failed to pass the eleven-plus entrance exam were embittered and envious. This inverted snobbery is rife in Sunderland and is almost an inherited disease.

As my family moved back into relative prosperity, I was labelled a ‘poshy’ by certain boys. My accent didn’t help either. My mother’s side of the family were all well-spoken and I lacked the harsh north-eastern twang that signified masculinity and toughness. I also wore my hair neatly parted, shined my shoes and wore my collar fastened and my tie in a Windsor knot, which I fancied looked more ‘sophisticated’ but I imagine made me look rather a pretentious prat, and I was always treated as an outsider – a situation I have come to realise is probably my natural habitat. Fortunately, I was strong enough to fend for myself and was never bullied, but if I had been less robust, I would have been a prime candidate.

Playing for the football team also helped. I was a fairly decent midfielder and that way became quite pally with some of the toughest boys in the school, who occupied all the other positions on the team. 1973–80 were extremely happy years. I made many, many friends and see them all still. In fact, I still go on annual jaunts to France with several of them. A couple I’ve known since primary school in 1966. They are quite simply my dearest friends.

My parents were extremely liberal and I was encouraged very early on to break free from the apron strings. I started work aged twelve in 1974, delivering newspapers underage, morning and night, six days a week, for £1 (£1.15 if no incorrect deliveries were made!). This seemed to me to be slave labour, so after a few weeks, I wrote to the local car dealer and asked if I could help wash his fleet of thirty-plus cars that stood on a forecourt. So, for the princely sum of £1.50, I worked from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Saturdays. In the summers, I worked on a farm nearby and another in Weardale, helping to bring in the hay from dawn till dusk for £6 a day and learning to shoot rabbits with the farmer’s gun and drive his tractor. Incredible to think I was only thirteen. The farmer would be jailed today!

I left home for university in September 1980. Getting to university was a minor miracle as I had messed around with my A level subjects to a reckless extent, starting off with history, politics and, bizarrely, biology. However, after several months, I decided that matters such as the reproductive cycle of the amoeba had failed to grip me and so I switched to economics.

But at the end of the lower sixth, bored by the Marxist soliloquies of the master, I ditched economics for English just two weeks before the end-of-year exams. Unsurprisingly, I managed an embarrassing 26 per cent, prompting W. K. Lewis to remark on my report, ‘Thurlbeck must seriously consider where his advantages lie.’

The following year, I had to cram two years into one, keeping up with the second-year syllabus while teaching myself the first year – including the heaviness of Milton and Chaucer.

Coupled with my self-inflicted burden was my complete reluctance to attend school at all. Weeks would go by without my making an appearance. Between January and Easter 1980, the staff had all but given up on me. Two weeks before the final exams, I crammed as much as I could, spouted it out and did well enough to satisfy the grade requirements for the universities in Manchester, Lancaster, Hull and Birmingham, and take the Bede School Rotary Prize for English.

My tolerant and encouraging English mistress, Mrs Pamela Atkinson, was my saving grace. I deserved to be slung out. But, instead, she wrote me a glittering testimonial which had impressed the four universities to such a degree, they all made me a conditional offer of a place without even asking me to interview.

I had jettisoned Hull and Birmingham as being too dull. And an eagerness to escape the urban griminess of Sunderland made me opt for Lancaster, which was close to my beloved Lake District, where I was to read English with the same haphazard approach as I did at school.

Before I left home, I sent Mrs Atkinson a bunch of flowers and a short note expressing my gratitude and thanks for having faith in such a wretch as I. She was a deep and thoughtful young woman, prone, as many deep and thoughtful young people are, to depression. She was also sensitive and shy. But she had the strength and independence of mind to ignore her superiors and refused to pigeonhole me as an idle loafer, and for that I will always be grateful to her. Four years ago, when I returned to my school to give a journalism lecture, I was distressed to learn of her death in her early sixties. An Old Bedan herself, she was a gifted teacher and I will be for ever in her debt.

My appearance at Lancaster got off to a flying start in the first year. A First in Theatre Studies and 2:1s in English and Philosophy. My portrayal of Jimmy Porter in Osborne’s Look Back in Anger also got me a First in my drama practical and, at 76 per cent, it was the highest mark in the year.

By now I had decided that drama was far more interesting than poring over a lot of Old Norse, Anglo-Saxon poetry and medieval literature. Accordingly, I decided to opt out of any pretension of having any scholarly leanings whatsoever and aim low. The exciting life of the wandering troubadour held its charms. And, to some extent, I’ve been governed by its itinerant principles ever since.

As an active member of the university theatre group and the Theatre Studies department, I took part in back-to-back plays for the next two years, leaving virtually no time for study. In April 1982, the Theatre Studies professor Tom Lawrenson died. He and I had been drinking Scotch into the small hours during the Easter vacation. Only after the best part of a bottle had been consumed did he tell me he was having his cataracts removed under general anaesthetic the following day and he had been warned not to drink the night before. Sadly, Tom died on the operating table from a severe stroke.

Professor T. E. Lawrenson was a founding father of Lancaster University in 1964, when he had originally been professor of French and one of the most revered academic figures in Europe. His memorial service in June was to be attended by leading academics from as far afield as Australia and the university decided to put on a play at the Nuffield Theatre in his honour and to entertain the eminent visitors, his students and the staff.

In a nod to Tom’s French scholastic backgound, Molière’s Le Malade Imaginaire was chosen, although performed in English. And the performance was to be marked as our Theatre Studies practical examination, which I was studying as a minor. I auditioned for the lead role of Argan and got it. I based the performance on my old politics master at school, Mr W. Fell. Bill Fell was an old Bedan and an old bachelor with a fussiness and unintentional line in comic hypochondria, which turned his lessons into a Whitehall farce. Perfect for the self-obsessed Argan. I’d frequently amused my friends at Bede with my impersonation of Bill Fell and the Theatre Studies department thought it would be funny too. Thanks to Bill, I got top marks in the year for a second year in a row, scoring 81 per cent and another First.

Lest I leave the impression that Bill Fell was in any way a foolish man, he was in fact a man of extraordinary brilliance. After leaving Bede as a multi-prizewinner, he took a Double First in history at Oxford during the early 1940s. In 1970, he completed a politics degree at Durham University in just a year instead of the usual three – taking a First. In his long career of teaching A level politics, he had just one failure. He was the most loved and respected schoolmaster I’ve ever come across. He is now no longer with us. But even his demise had its own academic comedy, with him believing in the end that he was in fact the Edwardian Liberal Prime Minister Henry Campbell-Bannerman. Lesser minds tend to opt for Napoleon. God bless you, Bill.

Playing opposite me in the play, as my maid Toinette, was a beautiful young woman with a mass of wavy brown curls and huge green eyes. I’d known her since 1964, when we were at Miss Richie’s nursery school together. She attended the local private Church High School for Girls, where I’d dated a few of her classmates, and I’d bumped into her at parties. Then she came to my sixth form to study for her A levels. On my first day at Lancaster, there she was again on my course and we became very good friends. She was frequently homesick and she felt like I was an older brother, and we laughed a lot too. We became extremely close but there was no question of us forming a relationship. We both had partners. I had a steady girlfriend from school who was at Liverpool University and she was dating one of my chums at Lancaster.

In 1987, four years after leaving Lancaster, a friend of hers passed me her number so I rang out of the blue and invited her for a drink. Another coincidence. She too had become a journalist. At Lancaster, I had always regarded her as my little sister. But standing before me was one of the most beautiful young women I’d ever seen. A petite size eight and with a heart-melting smile. Even though I’d known her since we were three years old, it had taken me until now to fall in love with her. And I did so on the very spot. In a little pub in Hampstead, where I lived. Within ten minutes, I had decided I would marry her. I proposed a few months later in a dingy guest house in the New Forest and, happily, she accepted.

We married in her old school church in February 1993 and a few months later our daughter Kate was born, followed by Phoebe five years later. ‘Boo’ and ‘Bee’, as they are known, have provided us with the happiest days of our lives. As my daughters get older, I preside over them with decreasing levels of influence. Alarmingly, my Christmas present from fourteen-year-old Bee this year was a cook’s apron emblazoned with the slogan ‘Prick with a fork’. There has always been a healthy disregard for authority in my family!

I had a wonderfully happy time at Lancaster. But I was never the most studious of pupils and my studies began to suffer. Shockingly, I only attended two lectures in three years and barely a handful of seminars. My tutors were despairing. To make matters worse, I did my usual absurdity of changing courses at the last minute, switching from single English honours to a joint English/Theatre Studies degree, which meant I had to cram two years into one. The decision just compounded the confusion and they could only award me a third.

I owed the library a fine of £3.50 and under the university rules they withheld my result until I paid it. I was so disinterested (I had started a job the day after my last exam in June 1983), I didn’t bother to pay and find out my degree result for five weeks. In fact, it was my father who paid it for me. This was a shameful episode and one which I regret to this day. My parents deserved much better from me and I still feel I let them down. I tell the story to illustrate how infuriatingly self-confident I was in those days. I really believed I could make a big splash in the world on my own and on my own terms. I was foolishly rebellious and possessed of an arrogance which wasn’t justified or attractive. I’m lucky to have kept all my friends.

I’m not one for self-psychoanalysis and I am not entirely certain what makes me so outwardly conventional and conservative and yet so absurdly hyper-independent and rebellious. The seeds of this contradictory nature might lie in my background. I am a mish-mash of old-fashioned, well-heeled middle-class entrepreneurs and mid-twentieth-century working-class street fighters. I belong to neither one nor the other. At school, I was never accepted as ‘one of the regular boys’. I was classed as a strong-willed, ‘posh’ eccentric. In the East India Club, I think I’m regarded as a brash, self-made northerner.

We never really know ourselves fully. But I am certain that I am very much an outsider and a loner. Even among my close circle of friends who I’ve known since I was five years old, I am the one who is ever so slightly on the periphery. Always last to make contact or be contacted and, in the 1980s, disappearing for years on end before strolling back.

On the Today newspaper, I was quickly pigeonholed by the news desk as a reporter to peel off from the rest of the Fleet Street pack to dig around on my own for an exclusive. On the News of the World, I worked alone and with very little guidance for the best part of two decades.

There were very few careers open to a man who was brash, pushy to the point of being aggressive, overly self-confident and armed with a third-class degree from a second-class university. Even fewer to one who couldn’t abide authority figures or take orders from anyone but himself.

At university, the only thing I excelled at was acting, gaining extremely good notices in the college and regional press and never anything less than a First in practical exams. Everything was on course for drama school and the stage. But while several of my contemporaries advanced in this direction (most notably Andy Serkis of Gollum fame and my close friend David Verrey, who went to the RSC and the National Theatre), I did my usual trick of changing the game plan at the last minute. I took my final bow in 1983, washed off the panstick, got my final First and never set foot on a stage again.

It was an odd and unexpected decision. But something my father had told me as a boy still resonated. Dad was a superb singer, possessed of a wonderful, light tenor voice. Coupled with his brilliantined good looks, immaculate dress sense and aura of debonair charm and bonhomie, he enjoyed success as a dance band crooner after the war. In 1952, while still nineteen, he made a record with the RAF Dance Band, ‘I’m Yours’. He sings it beautifully and I still have the original 78rpm record and it is the only recording I have of his voice at all. A picture of him in uniform singing into a large microphone looks down on me in my study.

Geraldo, the famous band leader, invited my dad to sing with his world-famous band. Although few under sixty will have heard of Geraldo now, this was rather like being invited to sing with One Direction today, or to duet with Robbie Williams. (Although, in those days, nowhere near as lucrative. The band leader took the royalties and paid his musicians and singers a simple living wage.)

Dad was tempted, of course. But he figured that living out of a suitcase all his life, ‘with no pension at the end of it’, was not a life for him. So he walked off that recording stage in 1952 and never sang commercially again. With hindsight, it was a sound decision. By 1955, the dance bands were no more, replaced by rock ’n’ roll. And Dad was no Elvis Presley! Geraldo managed to limp on as a cruise ship dance band until the early 1970s but the glory days of million-selling recordings were no more.

That recording is, of course, my most precious possession. By the time I married in 1993, he’d been dead four years, felled by an unexpected heart attack after a lifetime of robust health, aged just fifty-six. I still miss him and think of him every day.

But I was lucky to be able to play his record for the first dance at my wedding reception in Lumley Castle, Co. Durham, where many of his friends listened with tears in their eyes as my dad crooned the lyrics of ‘I’m Yours’ and his son danced the foxtrot with his new bride.

I briefly took the microphone to introduce my father’s record, ending with, ‘Take it away, Dad,’ and as I did, I registered briefly a look of puzzlement on the faces of his lifelong friends. Afterwards, I learned that none of them had any idea of his early singing career, such was his impeccable modesty. Only his mother had ever played the record. Over and over again, of course, as – like most women who knew my dad – she totally adored him, calling him her ‘little chun boy’. I still have no idea what a ‘chun boy’ is. I only hope it isn’t now something horribly racist!

So, like my father, I turned my back on the idea of settling into a show-business career. After three years of considering nothing else, I pulled off my usual routine. I threw everything up in the air and decided to try something else.

In 1984, I was living in the Lancashire mill town of Galgate with my girlfriend from university and I picked up a copy of The Guardian and turned to the situations vacant pages in the education section. The Sudanese Ministry of Education was looking for English teachers and we thought we’d apply.

Sudan was and still is a hostile country, ripped apart by civil wars and famine, and with a climate like no other. I recalled Alistair Cooke describing the climate on the radio once and his words had remained. ‘There may be hotter places in the world than Khartoum. But if there is, I don’t want to go there.’

By the summer of 1984, the famine which had decimated Ethiopia had swept into the Sudan and Chad, killing millions. Disease was rife and civil war was raging.

I was to be a sixth-form English master at a boys’ boarding school in a village about 120 km south of Khartoum called El Hosh, and my girlfriend would teach in the girls’ school. Our salary was the equivalent of £26 a week, which was roughly the same as we would have got on the dole in the UK. But in the Sudan, it put us in the top one per cent of salary earners.

We were met by a Sudanese teacher who showed us to our accommodation, assuring us as we walked that it was in fact ‘the best house in the village’. In truth, when we got there, it looked no more than two garages joined together with chicken wire for windows. But compared to the rest of the village, it was luxurious. Many of the villagers lived in shacks. Many lived in communities of mud huts.

We had a small, walled yard where the ground had been scorched hard by the sun. Two electric lights. One cold tap in the yard, which, at head height, also doubled as a ‘shower’. The lavatory was a hole in the ground at the bottom of the yard. And there were no mod cons. No TV, washing machine or cooker. Fortunately, we had come with a short-wave radio so it was possible to tune in to the BBC World Service, which was a godsend.

Washing, ironing, cooking and cleaning was carried out by a team of four maids, one for each job, as each task was a long labour in itself. And for their efforts, I paid them the equivalent of 10p a day. To pay a penny more would have incurred the anger of the villagers, as it would have led to increased wage demands elsewhere.

Washing had to be done by hand using a bar of soap in a three-foot washing pan the shape of a dinner plate. The drying was easy – clothes would be bone-dry and semi-bleached by the sun in minutes. A saturated towel would dry in fifteen minutes. My hair would dry on the 30-yard walk between the tap and our home.

Ironing was also labour intensive. There were no electric irons in the Sudan. Instead, hot charcoal was poured into primitive irons in much the same way our great-grandmothers used coal irons until the early 1920s.

Cooking had to be done on a small charcoal stove about twelve inches high and made from clay. There was just one ring to cook an entire meal. There were power cuts for days or weeks at a time, so candles were generally in use when the sun set at 6 p.m., which it did all year round. No electricity also meant no tap water, as the village pump ceased to work. A small earthenware pot, known as a ‘zir’, was constantly filled for emergency rations. In such cases, bathing with precious water became impossible and a ‘sand bath’ was used – handfuls of sand being rubbed across the body as a primitive exfoliant.

Food was scarce as the famine swept west from Ethiopia. Lentils one day, ful masri (Egyptian beans) the next, the occasional rotten tomato, and rice and bread peppered with grit. On starvation rations and with the chronic bacterial and amoebic dysentery which stuck me down with grim regularity, my weight plummeted.

Malaria was a killer in the area among the undernourished, especially young children. Mothers frequently appeared at the house or the school, holding a limp child and begging for anti-malarial chloroquine tablets, which I had in abundance. We doled them out like Smarties, fully expecting to be able to buy or bribe our way back into supplies with our ‘considerable’ salary.

When they finally ran out, I discovered none were available. The result was instant malaria, so I self-medicated as best I could with black tea and rest.

Teaching the boys in the Sudan wasn’t too hard. As it had been a British colony, English was a strong second language. And until the year before, when President Gaafar Nimeiry introduced strict Sharia law, it had been the language of teaching in all the schools. Even chemistry was taught in English.

Almost all the boys were Muslims and although they were boarders, their families all lived within a few hours’ drive from the school. But two or three Christian boys came from the south of the country and were totally isolated from their families. A trip home would take several days and was only affordable once a year.

Peter Malek Aywell and John Deng were two such boys and they regularly came to my home for free private tuition in English literature. They were from the very primitive Dinka tribe who were noted for their bravery and ferocity in battle. Peter and John were both over seven feet tall, which isn’t unusual among the Dinkas. Their faces were almost a purplish-black with scars carved into their heads and faces – the straight lines denoting their unflinching bravery while self-inflicting the wounds with a sharp knife. They were also as bright as any boy I had studied with. I taught Peter chess and after a dozen or so games, he was beating me. They also loved the short-wave radio and listened to the BBC avidly. Peter couldn’t listen to it without clutching it and resting it on the end of his knees!

Their visits were at their request and had soon become as much of a social gathering as anything. They were twenty-one (families had to save long and hard to send boys to school and students were often quite old) and I was twenty-two, so we were contemporaries and soon became good friends.

At school, class sizes were never below sixty, with five or six boys often sharing one textbook. There was no glass in the windows, causing sand to blow everywhere. And there were no teaching aids apart from a blackboard and chalk.

Sudan in 1984 was frozen in time. The former colony was granted independence in 1956, but the institutions which the British had installed remained and were largely unmodernised and falling into various states of disrepair. Steam trains still puffed along railway lines built by Kitchener at the end of the nineteenth century. Fuelled by charcoal, rather than the vastly superior coal, they barely exceeded 30mph. The most modern aeroplane was Sudan Airways’ ageing, second-hand 707s, reserved for long hauls. But many internal flights were carried out by ancient 1930s German Fokker biplanes with room for just thirty passengers. Alarmingly, they would leave a trail of thick black smoke pouring from their propellers as they droned through the air.

I never came across a home with a telephone. Calls were all made from the local post office and had to be booked in advance. My call to my parents in England had to be arranged two weeks before I wanted to make it. So we resorted to letters, which took six weeks to arrive.

Even the machinery of government was of a bygone era. At the Ministry of Education in Khartoum, they still had a vast typing pool of about 400 women, all in serried rows, methodically clattering out bureaucratic missives on shiny black, 1920s Imperial typewriters.

And the most popular mode of travel was on foot. Followed by donkey. Only the wealthiest could afford cars, the most popular model being the 1950s Hillman Minx.

When I washed up at home in the spring of 1984, unannounced, my father answered the door. When he opened it he stood in the doorframe looking blankly at his only son. Although it had only been a year since he had last seen me, he didn’t recognise me. My face was tanned and my hair was bleached by the Sudanese sun. But I had become unrecognisable due to my chronic weight loss. I stood on the bathroom scales. When I left the UK, I was 11st 6lbs. I was now 8st 10lbs. Even my muscles had wasted through illness and chronic food shortages. At 5ft 11in., I was skeletal.

Over the years, I’ve had a couple of trips to hospital or the doctor to deal with recurrent malaria. Both bouts hit me when I was on holiday, allowing me to maintain my family tradition of no Thurlbeck taking a day off work sick since 1915. The only other side effects are a propensity to tan in the merest blink of sunshine and an inclination to carry more weight in case I’m forced to face a starvation diet again. I have been 13 stone since I was twenty-five – about a stone overweight. But compared to the suffering of the Sudanese, through drought, famine, civil war, bullets, shrapnel and shell, I count myself lucky.

Despite the privations, the Sudan was a golden opportunity for adventure and for making contacts and plans. Some of the contacts I made during my travels I remain in touch with to this day. And my plan, on my return to England, was to become a journalist.