Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: D. QUIXOTE

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

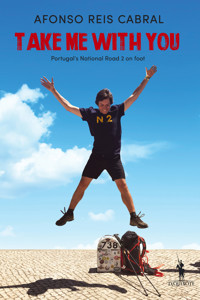

Portugal's National Road 2, at almost 739 kilometers long (459 miles), is the longest road in the country, and one of the longest in the world. It travels the length of Portugal from Chaves in the north to Faro in the South. With a mythical status and its own identity, it's the most beautiful route to travel if you want to get to know the people, landscapes, and the very heart of Portugal.The writer Afonso Reis Cabral, author of two novels and a collection of poems, decided to travel the length of the road on foot. For 24 days, walking alone, he let the road guide him: he crossed mountains and plains, plunged into rivers, walked through storms and sun. But most importantly, he stopped to talk with the people he met. At day's end, he would publish a post on his Facebook page, a diary written on his cell phone, relating the main events of that day's journey. With thousands of readers, comments, and shares, his posts inspired people far and wide.Now, in an expanded, illustrated version, this book is Afonso's travel diary of his journey along that mythical road. Traduzido por Tiffany Higgins

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 102

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Ficha Técnica

Title: Take Me with You—Portugal’s National Road 2 on Foot

Original title: Leva-me Contigo – Portugal a Pé pela Estrada Nacional 2

Editing: Maria do Rosário Pedreira

Translated by Tiffany Higgins

Cover design: Maria Manuel Lacerda / LeYa

Layout: César Marreiros, Mónica Dias and António Rosado / LeYa

Maps: Ricardo Coelho

Photos: AEQC (cover), Sílvia Silva, Luís Ferreira (top of page 80), João Reis Antão, José Vinagre, Carina Vinagre, Ana Bárbara Pedrosa. All the rest are the author’s photos.

ISBN: 9789722072045

Publicações Dom Quixote

(an imprint of Grupo LeYa)

Rua Cidade de Córdova, n.º 2

2610-038 Alfragide – Portugal

Tel. (+351) 21 427 22 00

Fax. (+351) 21 427 22 01

Copyright: © 2019, 2021, Afonso Reis Cabral and Publicações Dom Quixote

All rights reserved

www.dquixote.leya.com

www.leya.pt

AFONSO REIS CABRAL

Portugal’s National Road 2 on foot

“The Road goes ever on and on

Down from the door where it began.

Now far ahead the Road has gone,

And I must follow, if I can,

Pursuing it with eager feet,

Until it joins some larger way

Where many paths and errands meet.

And whither then? I cannot say.”

J. R. R. TOLKIEN, THE LORDOF THE RINGS

Don’t call me Ishmael. But some years ago—it’s not important how many—I too stood in the presence of the New York hordes walking toward the coast. And I think that, like Ishmael, all of us share the same instincts in relation to the sea. All throughout the city, on the roads that take you to the ocean, hundreds of mortals set their sights on the water.

They’re searching for a reflection, they look more inside than outside themselves, in search of the spirit of life. Melville told me this in not so many words, his words much better than mine, and Ishmael’s eagerness to make his way to the sea entered me like those beautiful ideas that never transform into beautiful things.

When I was thirteen, I travelled in a big truck to Germany, but that ride didn’t count because I hardly remember the spark of it, the ignition point of the fires and worries within. Later on, at twenty-five, I repeated the journey, but that also doesn’t count because I was trying to write a novel and, when you’re trying to write a novel, you’re not traveling—you’re trying to write a novel. In time, I dreamed of leaving Portugal aboard an oil tanker, maybe headed to Angola, and from there, bound for who knows where. Recently, I tried to set off in a submarine, but the Navy stopped me. Whenever I visit the bottom of the sea with the help of diving equipment, I never find, in that unsilent kingdom, what it has to give.

The thing is, the sea also gives us roads to the coast. In Portugal, where you only need to open your arms for your fingertips to touch the Cabo da Roca and Elvas, whatever road you take to the sea is too short. With the help of the wind, sometimes you can smell the sea air in Castelo Branco. From Bragança, on the clearest days, if you really squint your eyes, you catch sight of the blue alongside Viana do Castelo. And Lisbon is only sea, even if the sea is only a huge river. From the vantage point of our little places, perhaps Portugal itself —that ancestral ship—moored long ago, forever attracting us.

Though I still yearn to lose sight of land—to join a submarine crew, to depart on an oil tanker, to scrub the deck of a schooner—in the meantime, I decided to do what’s possible, which many times becomes impossible exactly because it’s within our reach: I decided to accept the sea’s challenge to go to the beach on foot, exactly because not all paths to get there are short.

The first time I heard talk of the road that’s not short was three years ago, when there were a lot of news articles about the identity of a certain National Road 2—conceived in 1945 in the Road Plan as a way to link the country in a thread extending well into the interior. When the highways were constructed, the National lost its status as a connecting route, but we were left with the stretch linking Chaves to Faro. Ready to be rediscovered. These days, motorcycles, cars, motor homes, and bicycles whizz through it with the urgency of someone who’s correcting an error. There are eleven districts, thirty-five counties, eleven cities, dozens of villages and hamlets, various mountain chains and many rivers, among them the Douro, Mondego, and Tejo Rivers. And there’s also everything you can’t render in numbers, like the birds songs and people’s lives.

But it was only at the beginning of this year that I noticed that the National Road 2 is the longest route in Portugal to get to the beach on foot. The dance between the highway and the sea extends for 738.5 kilometers. It’s a very quiet dance, because the asphalt doesn’t move, and so the sea has to be all wavy to woo her. Or maybe they’ve actually never met, the road and the sea, since the National 2 finishes in the center of Faro, before ever having caught sight of the Ria Formosa coastal inlet or the ocean.

It also occurred to me that I should really be an expert at diving into the waves after weeks on the road using only my feet, legs, muscles, and will. I didn’t view myself as a masochist; I instead felt like my body was appeased after all that exertion. Hot in the cold water.

The physical appeal combined with my desire for an analog life. The bodies of my generation have digital parts. Our fingertips are worn off from swiping pixels on screens. There’s a part of our cerebral cortex that feels pleasure only from algorithms. I’m not against our artificial intelligence, but I felt myself attracted to a more vivid kind of experience. Genuine because it doesn’t depend on monitors. Eyes gazing without filters, legs walking just to walk.

In a society in which being young is praised as something worthwhile, though worth and merit are exactly what we’re trying to capture, not what’s given to us, I intended to make the road a torture I’d remember getting through. A sacrifice that would mark the passage from youth to the other side, but still would have some creature comforts.

But there was something wrong about the project. I would always be kept company by a guy I can never lay to rest—me. The more I walked, he’d take the same steps, my steps, toward the sea. To give him the slip, I proposed to always meet new people as much as I could, new characters. Luckily, the many kilometers of the National 2 would bring loads of people.

I feel like I’m about to prove myself. To reveal something that’s only mine, like the oyster when it’s relinquishing its pearl. I believe not everything has to be explained, though this excuse serves perfectly: I decided to leave because it appealed to me.

Some people I talked to about this project called me stupid —as I perceive them to be, too—but I maintained a good attitude, imagining that the road would make us part of it. I’d even bought a Forrest Gump hat.

I set the 22nd of April, soon after Easter, as the departure date. If I didn’t end up injured or worse out there, I’d arrive in Faro in less than a month. At the end of the journey, like the explorer Richard Byrd, maybe I too could say of the road that leads to the sea: “Part of me remained [there] forever […] what survived of my youth, my vanity, perhaps, and certainly my skepticism.”

Useful things are always preceded by useless things. The latter, the ones born in your head, range from the smallest to the biggest. In my office there’s an artist who also works there. He set up shop in the kitchen because of the light, which enters through a tiny window, a sort of camera obscura, and he brought with him white canvases and virgin wood and slabs of clay to sculpt. The sculptures would break, many times by accident—I like anatomically perfect statues with amputated heads and arms, too—but the canvases never stay there long without getting filled up. I don’t know much about how all that gets born. He puts down the colors and the colors arrange themselves into feminine figures, forests, ballerinas, and faces of horror. But I know that, before putting paint onto the tip of the brush, these were useless things in his head. These useless things, treated with the care they deserve, end up as useful things on the canvas. Everything that’s beautiful is useful.

After I’d decided to leave, the road wrapped itself around my thoughts like a boa constrictor several kilometers long. Instead of asphalt, there was the fear of not being able to do it, the mania of certain hours where I believed myself capable of everything, including walking from the Shire to Mordor, the dejection of having agreed to a futile idea that came from nothing and would lead to nothing. And the determination to see—to go—to have life run through me. Now, the road was my canvas and I would act like its painter, filling it with useless things waiting for the colors that would transform it into a painting.

One day in March, I began walking after breakfast. I passed a motorcycle and started following it, and kept going. I passed a car and followed it, and kept going. I hadn’t told my legs to go, but they must have believed that my brain had already wasted many days on useless things. The hour of useful things had come, like training the body. Two hours later, I caught sight of the office, which was eight kilometers from my house. I had grown two blisters on my left foot—the same ones that later, returning to my house, would beg me to buy proper shoes right away—but my journey on the National 2 had begun.

I’ve never been in the starting blocks at a race. I imagine the competitors in position, the bodies hot and tense, the stands in silence, waiting for the signal. I find that vision, which I associate with a sort of peace, in the Decathalon sporting goods store. Everything in this store is ready to go: the shelves of equipment, the tents in a row, the inflatable boats, the compresses for your aches and pains, the bicycles, the punching bags. There, little paradises or large tortures await you. I was thinking about this when I asked the saleswoman for the fifth time: “But are you really sure these boots will hold up well on the road?” She was hesitant about the idea of 738 kilometers in Redmond Columbia boots for seventy-nine Euros, but as they were the only ones in my size, she informed me that they’d hold up, and I was satisfied. Many weeks later, in the morning I arrived at Faro, I kissed the boots, grateful they’d withstood what the road and I had done to them.

Next, I bought the kind of paraphernalia that is a lifesaver on the road: a forty-liter backpack with ventilation panels, various pockets, and a rain fly; plastic two-liter bladder for water, equipped with a tube and water bottle; a first-aid kit; yellow jacket, a kind of second skin; fifteen pairs of anti-blister socks; various kinds of lotion to keep your feet well-hydrated; hat with neck protection; a charger to keep on feeding my mobile phone.

In the training days that followed, I discovered that on two feet you see more than on four wheels. At least, you see it more slowly.

Lisbon is surrounded by gardens; in the Parque das Nações, you can ask the few remaining farmers how to weed. Sometimes they don’t respond, but I tell them that I’d like to have a garden like theirs. Sometime you find that there are too few fields for too many people. The problem is the real estate market.