Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

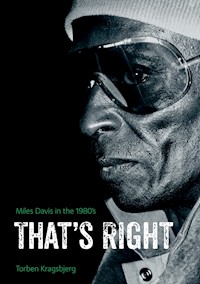

If you want a closer look into what happened with Miles Davis' music in the 1980's, this is the book for you. 10 years ago I planned an updated Danish version of my dissertation "That's Right" from 1991. The project stranded because of financial shortcomings. Things have changed, and this book is a result of that. The dissertation looks at the music Miles Davis recorded in the 1980's. The historic context is described. Miles Davis as an improviser is described and analysed. Focus is on "Blues", "Spanish modes", "Pop" and "Modern composition". The esthetic guidelines he used are stated. When you go to page one you are back in time in the year of 1991. A few more recent comments and explanations have been included.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 169

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dedicated to Vita Anna Kragsbjerg

Contents

PREFACE

INTRODUCTION

MILES DAVIS IN ABSENTIA

Weather Report

Mahavishnu Orchestra

Return To Forever

Headhunters

Keith Jarrett

Other relevant musicians and trends

Miles Davis in the 1970s

DELIMITATION OF MATERIAL

THE ANALYSIS

Blues

Star People (18‘44)

It Gets Better

That’s Right (11’11)

Violet (9’01)

Tutu (5’15)

Pop

Human Nature (4’30)

Time After Time (3’37)

Something Is On Your Mind (6’40)

Perfect Way (4’32)

Spanish modes

Portia (6’18)

Lost In Madrid

Theme For Augustine (4’32)

Claire (2’23)

Siesta (5‘10)

Los Feliz (4’34)

Modern composition

Orange (8‘33)

Green, part 2 (4’10)

White (6‘02)

Blue (6’33)

Summary

The basis for improvisation

Improvisation

The use of oplæg

Roots, seeking the origin.

The use of the Harmon mute

Phrasing

The tradition of speechy and textual related instrumental playing

The outer language limit

Aesthetic guidelines

PERSPECTIVISATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DISCOGRAPHY

BEING A RESONANT BEING

A SPECIAL THANKS TO …

APPENDIX

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Appendix 5

Appendix 6

Appendix 7

Appendix 8

Appendix 9

Appendix 10

Appendix 11

Appendix 12

Appendix 13

Appendix 14

Appendix 15

Preface

This dissertation has, as its background, my interest of approx. 10 years in Miles Davis’ music. Secondly, as a student and as an active jazz musician, I have benefited from the contributions to this genre which Davis made over time. Many of his record releases have also been no less than musical revelations for me. The title That’s Right has been selected for several reasons. With its conciseness it represents Davis’ work by reducing things to the bare essentials. The actual recording of That’s Right, which is part of the analysis, is a study in blue and thus of a colour and of a mood. It was only when analysing this recording that my ears went open to the oral analogy that Davis’ music contains.

Davis views his records as guides to his concerts at a given time, and it appears to be a paradox when he claims that a concert is at its worst, when the music sounds like the record. But the point is that this music is constantly changing, as it is primarily created in the moment, as a constant exploration of moods and colours. Colours from all over the spectrum allow dark and light to meet, or have countless shades within the same tone. Colour compositions which allow colours to be blended or to exist separately, but which, nonetheless, result in a whole. Colours which are left alone, possibly to be taken up again. Colours which are limited to a shade allow light and dark to be divided and are only kept in one tone. A colour that rests in itself, but still contains a diversity. Colours and moods …

Introduction

This thesis will examine Miles Davis’ music from the 1980s and attempt to characterise it based on recordings of the four main groups of blues, pop, Spanish modes and modern composition. These main groups are all rooted far back in Davis’ production, examples of which from before 1980 will be provided in what follows. Following the introduction, the development of contemporary music during Davis’ absence in the years ‘75-80 will be illustrated under the headline Miles Davis in absentia. Music related to that of Davis will be described with the intention of identifying differences and similarities between Davis’ music from the beginning of the ‘70s and ‘80s, respectively.

As basis for selecting material for examining in each of the four main groups, the known recordings will be delimited. The possibility of making an adequate characteristic of Davis’ music from the ‘80s by applying this delimitation will be discussed. Subsequently, the analysis methodology applied to the selected material will be presented. The subsequent analysis presents blues as the first main group followed by pop, Spanish modes and modern composition. The summary is begun with a description of the basis for improvisation as it was at the time. Then follows an attempt to summarise the analyses of the improvised solos presented in the preceding text. This is done by breaking down the solos into whether they include a climax or not. In continuation of this, it is attempted to make an overall interpretation of the content of the improvisations. Davis’ use of the Harmon mute is highly relevant when trying to capture his improvisatorial style. A description is therefore provided of the use of this mute. In continuation of this, Davis’ phrasing is examined, and the background for the subsequently applied analogy to the spoken language and its outer limit will be given. Examples will be provided from jazz tradition of known uses of imitations of spoken language. This is pursued in the subsequent text as the outer language limit is described and the use of imitations of it is identified from the analysis. The ending of the summary provides a number of aesthetic guidelines once and once again presented by Davis and which have been exemplified in the preceding text.

“The very first thing I remember in my early childhood is a flame, a blue flame jumping off a gas stove somebody lit … I saw that flame and felt the hotness of it close to my face … The fear I had was almost like an invitation, a challenge to go forward into something I knew nothing about.”1

It is hardly a coincidence that Miles Davis starts his autobiography by describing a blue flame that gave him an unsettling experience. For since he started as a professional musician around 1945, blue has characterised the music he chose to play. First and foremost as blues. In the beginning of Davis’ career, bebop music was the prevailing style. Blues was often played in fast tempi with extended chords and distinctive embellished melody.

Since then, Davis left his own mark on the blues. For instance with the modal blues, Freddie Freeloader and All Blues, from the album Kind Of Blue (‘59). In the following years, Davis played the blues on this background and based on more common versions of the blues. Around ‘69, Davis, exhibiting his usual ability to turn his back on the past and set a new course, said:

I was telling Herbie2 the other day: “We’re not going to play the blues anymore. Let the white folks have the blues … Play something else.”3

With these words, Davis seems to say goodbye to the blues, but in reality, he only said goodbye to the too obvious versions of blues. On the album Big Fun (‘74), the blues chord progression was disrupted and reformed in a new manner in the recording Go Ahead John.4 The album Get Up With It (‘74) also applied blues as its vantage point. Accordingly, Red China Blues is rhythm & blues-inspired, and Honky Tonk reduces the harmonious content to a two-chord vamp. In Davis, the blues is first and foremost known as a mood, since form, harmony and other characteristics are often altered. A mood that can also be applied in recordings which do not otherwise make use of blues characteristics by using the blues scale.

Popular songs, or standards, were a key part of the bebop repertoire and thus part of the music Davis started his career playing. They originate from movies, revues, shows and recordings and were composed by George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Irving Berlin, etc. It is remarkable that from the mid-’60s and until ‘75, no standards were recorded. The word pop emerged in the mid-’50s. Pop relates to the teenage audience that was the main buyer of popular music at the time. It changed character with the emergence of rock. To illustrate the two concepts, Frank Sinatra can be said to represent popular songs, while Elvis Presley represents pop. From the mid-’60s to the end of the ‘70s, contemporary music was the preoccupied with experimenting, often seeking a raw expression far removed from that of pop. This raw expression was refined with the emergence of symphonic rock. Around ‘80, pop music once again had a place where the combination of wide attention and experimenting was possible. Only, now in a different manner as represented by e.g. Prince.

In respect of the Spanish modes, it seems that their parallel to blues was what fascinated Davis: ““Solea” is a basic form of flamenco. It’s a song about loneliness, about longing and lament. It’s close to the American black feeling in the blues.”5 The Spanish inspiration is already introduced on the album Miles Ahead (‘57) with the recordings The Maids Of Cadiz and Blues For Pablo6. The album Sketches Of Spain (‘60) solely makes use of Spanish modes, only now in a relatively pure, folkloric version. On both albums, Davis is the soloist accompanied by arranger and composer Gil Evans’ ensemble. However, Davis also used the Spanish modes in his combo recordings, e.g. on the album Kind Of Blue (‘59) in the Flamenco Sketches recording. As a final example, it is worth mentioning the recording Spanish Key from the album Big Fun (‘74) where the Spanish modes are used more freely.

Davis’ earliest inspiration from modern composition is evident in the collaborations he had with Gil Evans. Already on the album The Birth Of The Cool (‘50), Davis’ works with an atypical instrumentation for jazz. Accordingly, the album featured tuba and French horn. The classic-inspired instrumentations are characteristic for the early collaboration between Evans and Davis. These instruments were also used on the albums Miles Ahead (‘57), Porgy And Bess (‘58) and Sketches Of Spain (‘60) with large ensembles. Sketches Of Spain includes a recording of Rodrigo’s Concierto De Aranjuez, originally a concert for Spanish guitar, but in Evans’ arrangement with Davis’ trumpet as the solo part. Besides the inspiration from jazz tradition, including Duke Ellington, Evans’ arrangements particularly show inspiration from Maurice Ravel, but also Igor Stravinsky. In the years leading up to ‘75, the influence on Davis from modern composition is represented by the inspiration from Paul Buckmaster and Karlheinz Stockhausen. This influence was used in fusion with other elements, and often, even this music would have a blue undertone.

1 Autobiography, p. 11

2 Hancock

3 Milestones 2, p. 136

4 Cf. T. Mortensen, p. 49

5 Autobiography, p. 242

6 Picasso

Miles Davis in absentia

The period leading up to Miles Davis’ re-emergence on the stage in 1980 will be examined for two reasons: partly to be able to assess the development of related music during his absence and its influence on his music in 1980, partly to attempt to uncover elements used from the time immediately preceding the inactive period. This will be illustrated by following some of the musicians from Davis’ band around ‘70. It appears that these musicians, considering the projects they have participated in, have had a considerable influence on this area of contemporary music. Davis’ music until ‘75 will be described in short and ties will be drawn to the vantage point he chose in ‘80.

It is characteristic that all these musicians more or less have worked with funk as an ingredient in the music they chose to play. In a number of interviews7, the common thread is that they are inspired by musicians like James Brown and Sly and the Family Stone. Another trend seems to be symphonically conditioned, meaning that it involves working with classic musicians, partly as an extension of the combo format that was common nature in jazz, but also as actual collaborations between two different ensembles. This trend has proven paramount to the development of the music, since even ensembles without classically trained musicians now had access to the orchestral sound that traditionally was only found in symphonic orchestras. New technologies were also applied in music where, for instance, the synthesizer had many uses. Some of these uses are linked to sounds which resemble the strings section of a symphonic orchestra. The possibility of long, sustained chords was a new in a combo context.

The wha-wha pedal, initially known from Jimi Hendrix’ use, was now used in various contexts, including in connection with bass and particularly Fender-Rhodes. It is worth taking a retrospective look, since Miles Davis also used the wha-wha pedal in the years leading up to this period, at which time he used it together with the direct electrical amplification of the trumpet. This completed the ring since the effect is originally known from the early jazz, which used wha-wha mutes for trumpets and trombones. The new technology obviously did not only provide electronic imitations of acoustic instruments, but also various opportunities which were distinctly electronic and therefore also new and unexplored.

A third overall trend is the use of ethnic music retrieved from near and far. This influence in particular is manifested in the introduction of a wide range of new percussion instruments and thus affects the rhythmical foundation of the music. In many cases, the ethnic inspiration affects the music more than the rhythm.

The period was characterised by an interest in different religions. This included religions which were obvious choices in relation to the musically ethnic inspiration, but interest was also shown in relatively new religions.

Weather Report

In the Weather Report ensemble, Joe Zawinul and Wayne Shorter found a playground for various sound and rhythmical experiments. From the beginning, it involved taking inspiration from ethnic music, e.g. based on Shorter’s year-long break as an active musician from the end of ‘69. During that time, he studied e.g. Ima Sumac, Peruvian and Latin-American music. Zawinul also studied the music of various cultures and he believed that “The mixing of races and the mixing of cultures create the greatest of all things.”8 He also talks about his joy of e.g. Arabian music, which has “everything”: African and European influences besides the distinctive Arabian.

The Weather Report style was in the making in the years leading up to ‘75, and it is typical that the album Talespinnin’ (‘75) states Zawinul as “Orchestrator”, because this album involved an arrangement and orchestration to an extent that was unusual in a combo context. However, it was done without losing the natural laid-back attitude that also characterise the music. The reason for this can be that the arranged music was always accompanied by an improvisatorial element. The ensemble also used collective improvisation, a practice that was already formulated on the cover of the first album as: “We always solo, and we never solo.”9 This sentence has become typical for all of the band’s production. It is characteristic of Weather Report’s music that the naive and high-technological co-exist and that something essential of Zawinul’s orchestrations is the playing that occurs when a melodica is followed by a synthesizer or when wordless singing suddenly overtakes a melody line. – A playing of similarity and dissimilarity. In ‘75, Zawinul tallies the key instrument he uses: piano, two ARP 2600 synthesizers, Fender-Rhodes (electric piano) with the effects Phase-shifter, Echoplex and wha-wha pedal. That is to say, relatively few means seen from today’s perspective. The effects were also used by the band’s bass player.

The albums Mysterious Traveller (‘74) and Black Market (‘76) use tape sequences which are applied to the actual recording. Nubian Sundance from the first album has an accompanying recording of large excited crowd. It runs in parallel with the remaining soundscape and is muted or comes to the foreground and so helps to condense or dilute the intensity in various places of the recording. The Black Market album also uses a number of short tape recordings at the beginning and end of several of the recordings as mood-creating preludes and postludes. The ensemble had its big breakthrough with the album Heavy Weather (‘77), and with the bass player Jaco Pastorius, it now had a musician who, at the time, had his own, new sound and who was able to take on the roles required and contribute with a new take on these roles. Some of them include: giving the music a foundation by means of ostinato or walking play, playing melody lines in e.g. harmony and chord progressions. With Pastorius joining the ensemble, the use of wha-wha pedal on the bass was dropped. As a soloist, he gave the ensemble a somewhat different profile. This was in part due to his bebop-based style, but also a very outgoing stage presence. The way Pastorius took on the bass role was largely adopted by those who succeeded him in the ensemble. In the time after the Heavy Weather album, this now more defined style was continued, only now without a percussionist.

The community created by Zawinul and Shorter was i.a. based on the view that music cannot be viewed in isolation of the musician’s life, but that it in fact springs from it. This view is part of the teachings of Nichiren Shoshu Buddhism – a religion that Shorter had had ties to since ‘74.

Mahavishnu Orchestra

The breakup of the first Mahavishnu Orchestra in ‘73 and the formation of the new ensemble allowed John McLaughlin to realise a number of projects where a modern jazz/rock combo with strong Indian inspiration was combined with the classic tradition. On the Apocalypse album (‘74), the classic is represented by London Symphony Orchestra, which in Michael Gibbs’ arrangements of McLaughlin’s music adds elements from late romanticism and early modernism. This combination is in itself an experiment, and the two ensembles are used in contrast to each other as a surprising effect, whith the symphony orchestra as underscore for the combo and with smooth transitions. Irregular time signatures are widely used, and with new rhythmical variants. For instance, shuffle rhythm with cross-sticks10, which lends it a Latin-American feel, or funk in an irregular time signature.11 In many ways, the album Visions Of The Emerald Beyond (‘75) is a continuation of the Apocalypse idea, but now so that the classic element has been reduced to constitute an extension of the combo with a string trio and two wind players, who are, however, mainly used for riffs in the more funk-oriented passages. As its predecessor, this album explores irregular time signatures and surprising juxtapositions, partly in the manner in which the recordings follow each other, but often also within the individual recording. An example of the latter is Faith, where a 5/4 harmony progression is played on a steel-string acoustic guitar with drum and bass accompaniment and gets a still higher melody line by an electric violin, before breaking off to an unaccompanied electric guitar cadence that soon finds a very quick-tempoed rhythmic ostinato, which triggers the theme that has been recurrent for the entire album, then a person laughs and suddenly we hear a triad in second inversion resolution on the organ. All these elements are run through during the very short duration of the recording of 1’59. The album also features electronic sound experiments, Pegasus, string quartet, reminiscent of Bela Bartok, Opus 1, and a duo for heavily distorted guitar and drums, On The Way Home to Earth, with a parallel in the duo playing which John Coltrane favoured playing with either Elvin Jones or Rashied Ali. On the Lp the three recordings immediately succeed each other and have largely been chosen as a contrast to each other. In the years ‘76-78, McLaughlin solely played acoustic music in the group Shakti. This group played music that was much more Indian inspired and featured Indian percussion, violin and custom-built steel-string acoustic guitar. The influence Indian culture had on McLaughlin springs from a religious interest in the teachings of spiritual leader Sri Chinmoy and thus the idea of a cosmic connection. This seems to have furthered the work with elements which, from a western perspective, at first seem incompatible. McLaughlin returns to electric music in ‘79.

Return To Forever

Chick Corea also studied ethnic music; particularly Spanish, Cuban and African music had his interest. He formed Return to Forever in ‘73, which explored the opportunities of the new electronic music. Corea himself points out that even in this ensemble, the music had a Latin-American, Brazilian inspiration12