Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Batsford

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

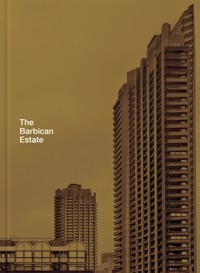

A beautifully produced book to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Grade II listed brutalist icon, the Barbican Estate. 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of the first residents moving into the Barbican Estate in London. This new book is a celebration of this unique complex – looking at the design of the individual flats as well as its status as a brutalist icon. Author and designer Stefi Orazi interviews residents past and present, giving an insight into how life on the estate has changed over the decades. The complex, designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, is now Grade II listed, and is one of the world's most well-known examples of brutalist architecture. Its three towers – Cromwell, Shakespeare and Lauderdale – are among London's tallest residential spaces and the estate is a landmark of the city. This is a beautifully illustrated, comprehensive guide to the estate, with newly commissioned photography by Christoffer Rudquist. It will show in detail each of the 140 different flat types, including newly drawn drawings of the flats as well as original plans and maps. Includes fascinating texts by leading architects and design critics, including John Allan of Avanti Architects on the unique building materials and fittings of the flats, and Charles Holland of Charles Holland Architects (and FAT co-founder) on the home and how these concrete towers have become such an integral part of Britain's domestic and architectural history.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 67

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

TheBarbicanEstate

TheBarbicanEstate

Stefi Orazi

PhotographyChristoffer Rudquist

Contents

Foreword

Barbican: The Unique Urban Vision

John Allan

Exterior

Penthouse and Pavement

Charles Holland

Flat types

A Recollection of Joe Chamberlin, Geoffry Powell and Christoph Bon

Polly Powell

Archival material

Number of flat types

Barbican blocks

Contributors’ biographies

Foreword

Stefi Orazi

I remember very vividly the first time I visited the Barbican estate. It was 1997, I had just graduated from university and got a job as a junior designer for the men’s magazine GQ. It was a hot summer and the Labour government had just got into power. I was broke and in debt, but it didn’t matter – there was positivity in the air.

After a work night out in Soho a group of us ended up going to the art director’s flat in the Barbican. I’d visited the Arts Centre once before, but apart from that I hadn’t even realized there were apartments and people living there. It was late and we were all a bit merry as we walked across Gilbert Bridge, it was also dark so I couldn’t really see much. We got into the lift, up to the sixth floor and into his (Type 36) apartment and I was speechless. A huge double-height living space, walls painted in Corbusian bright colours, simply furnished, books everywhere, wooden open-tread stairs – it was stunning. We all cooed as Tony explained the curiosities of the Barbican such the Garchey waste disposal system and the underfloor heating. Some of us ended up staying over and in the morning I had to navigate my way through the estate to the tube station.

In the daylight Gilbert Bridge, which spans the Barbican lake, was a totally different experience. To one side of the bridge was the waterfall, and on the other, fountains – what the hell was this amazing place?! And so it was by pure luck that a few weeks later, having found myself with nowhere to live, that Tony suggested I could stay in his spare room for a while, the only caveat being that he had ‘this funny man that taught at the Guildhall School of Music, who lodged in that room for a night or two once a month or so’ – a situation that we still laugh about to this day.

What was meant to be a few months ended up being eight years, and a love affair with Barbican and its architecture ever since. At that time the Barbican hadn’t reached the fashionable brutalist status it has today. It was like our little secret. Most people still thought it as ugly, an eyesore sometimes topping polls as Britain’s ugliest building. It was (and often still is) perceived as a council estate. A notion that seemed bizarre to me, having grown up in one. I’d never come across a council estate that was so impeccably designed and maintained. Stairs, lifts, lobbies cleaned and mopped every day. Rubbish collected from a nifty little two-way cupboard daily, with milk delivered to the cupboard above. Private gardens that were pruned and watered to perfection and the Arts Centre literally a lift ride away. This really was a utopia.

After living in the Barbican I moved to neighbouring Golden Lane Estate (also by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon) and then back to the Barbican until my eventual move out of the City in 2015. During those 18 years I saw the demographic and the perception of the Barbican completely transform. Had I been smart enough, I would have started saving to put a deposit down on a flat in those early days. A typical Barbican resident back then would have been a middle-aged City worker. The Barbican was convenient for them location-wise, and very safe, and if the exterior was not to their taste that was okay, as you could chintz-up the inside of your apartment to your heart’s content. I remember there was a family with children in the apartment across the corridor from us, but apart from them I don’t remember seeing any other children. The residents’ gardens were barren and in the summer I was often the only person sunbathing there. I don’t know when it started to change, but slowly and surely my best-kept secret was no longer a secret. The Barbican began to be appreciated. Designers, artists and architects with young families began to move in and today the gardens are populated with children running about. As they should be and as the architects envisaged.

I didn’t know much about the architects or the history at the time of moving there, but living in such a place it’s impossible not to wonder how such a complete new part of the city came to be realized, and in such an uncompromising way. Much has been written about Chamberlin, Powell and Bon and the history of the Barbican and why it was built in the post-war devastated part of the City, which John Allan briefly touches upon in his essay here. But what and who makes the Barbican function? Who are the people that moved there in those early days, and who is choosing to live there today? With its housing across 20 different blocks, 2,000 plus apartments in more than 140 different typologies – from tiny studios to town houses – it is this that fascinates me, and what I wanted to capture in this book. Next year, 2019, will mark the 50th anniversary of the first residents moving into the estate and it seemed like a perfect opportunity to celebrate the Barbican – a unique and special place. It’s hard to imagine anything like it ever being built again.

I am hugely grateful to all the residents who kindly allowed us to photograph their homes, and to those who put me in touch with people on my ‘hit list of flat types I have to photograph’. I’d also like to express my gratitude to the people I have interviewed. I especially want to thank Polly Powell, daughter of the architect Geoffry Powell, for her support, and the staff at Batsford for their invaluable input. A special thank you to Christoffer Rudquist for his incredible photography, his absolute commitment and enthusiasm and for completely ‘getting’ the project. Lastly I would like to thank Tony Chambers for renting out his spare room to me for ‘a short while’.

BarbicanThe Unique Urban Vision

John Allan

The Barbican estate in the City of London is the most complete realization of a Corbusian vision of modern urbanism anywhere in Britain. As the achievement of a receding era, it has now become increasingly hard to comprehend how a work of such magnitude and tenacity was accomplished, and impossible to imagine that anything of comparable ambition could ever be achieved again. It is witness to an order of civic valour of which this country no longer seems capable.

The enormous time-span of the Barbican’s creation – some 30 years from earliest discussions to the opening of the Arts Centre, the final element of the complex, in 1982 – seems curiously linked to its turbulent critical fortunes. Like some mighty cargo vessel defying the incessant sea changes of an ocean-going voyage it has confronted and endured all the vagaries of architectural taste before reaching the safe harbour of listing in 2002, though even this imprimatur was not without controversy. Something of this contested reputation must surely be attributable to its sheer scale and the difficulty of finding suitable comparators. We must look beyond modern times to find similar endeavours in British city building – to Edinburgh New Town perhaps or the works of Regency London by John Nash, or some of the grander infrastructure of the Victorian era. It is surely less from a coincidence of style with popularity than from the eventual acknowledgement of the Barbican’s unimpeachable integrity that this hard-earned recognition ultimately stems.