Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

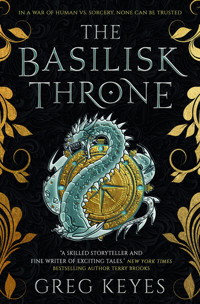

Master and Commander meets A Game of Thrones and Pirates of the Carribean. Rapid-paced high fantasy with all-out combat on the high seas, and a canny young woman who faces the hidden threats of an imperial court. Yet the key to defeating a sorcerous enemy may lie with a wild rogue and the slave of a maniac. For centuries the Drehhu have ruled every continent, brutally enslaving the human inhabitants. Now after endless wars the human empires of Ophion, Velesa, and Modjal have pushed the inhuman enemy back to their heartland and unite in a final, massive assault. Alastor Nevelon and his son Crespin set sail against the Drehhu, and they have their own secret weapons. Yet Alastor is forced to send his daughter Chrysanthe to the capitol city Ophion Magne as a "token" of his loyalty to the emperor. He instructs Chrysanthe to use her considerable intellect to discover what plots may be afoot, even as she enters a place where courtly manners hide murderous intent. As nations collide the true key to defeating the Drehhu may lie in a remote mountain stronghold, with a wild rogue known as Hound and Ammolite, the young slave of a sorcerer more ancient than any nation―whose loyalties remain threateningly unknown.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 607

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

Dedication

The Battle of the Expiry

Book One: The Cost of Sugar

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Book Two: The Price of Passage

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Book Three: The Terms of Exchange

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Book Four: The Dues of Treason

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Praise for Greg Keyes

“Keyes mixes cultures, religions, institutions and languages with rare skill… the rewards [are] enormously worthwhile.”

Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Here is a high fantasy novel that has the grit of secular combat and the heart of one of the great romances.”

Fantasy and Science Fiction Magazine

“Recommended… Keyes’s talent for world crafting and storytelling make this series opener a strong addition to fantasy collections.”

Library Journal

“Keyes takes all the genre’s conventions and, while never overstepping their boundaries, breathes new life into them.”

Kirkus Reviews

“Keyes is a master of world building and of quirky characters who grow into their relationships in unexpected ways.”

Booklist

“Greg Keyes has always been both a skilled storyteller and fine writer of exciting tales.”

Terry Brooks, author of The Sword of Shannara

“Starts in the realm of normalcy and quickly descends into the favorably bizarre and surprising… there was not one character that was uninteresting. The world building is epic.”

Koeur’s Book Reviews

“Strong world building and superior storytelling.”

Library Journal

“[A] sophisticated and intelligent high fantasy epic.”

Publishers Weekly

“A graceful, artful tale from a master storyteller.”

Elizabeth Haydon, bestselling author of Prophesy: Child of Earth,

“The characters in The Briar King absolutely brim with life… Keyes hooked me from the first page.”

Charles de Lint, award-winning author of Forests of the Heart and The Onion Girl

Also by Greg Keyes

Kingdoms of Thorn and Bone:

The Briar King

The Charnel Prince

The Blood Knight

The Born Queen

The Age of Unreason:

Newton’s Cannon

A Calculus of Angels

Empire of Unreason

The Shadows of God

The High and Faraway:

The Reign of the Departed

The Kingdoms of the Cursed

The Realm of the Deathless

Interstellar

Godzilla: King of Monsters

Godzilla vs. Kong

Dawn of the Planet of the Apes: Firestorm

War for the Planet of the Apes: Revelations

Marvel’s Avengers: The Extinction Key

Pacific Rim

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

The Basilisk Throne

Print edition ISBN: 9781789095487

E-book edition ISBN: 9781789095494

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2023

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental. The publisher does not have control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Greg Keyes asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

Copyright © 2023 Greg Keyes. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

For Sandra Baxter

THE BATTLE OF THE EXPIRY

988 E.N.

“HARD ABOUT!” Captain Salemon shouted, as half of their prow disintegrated into a cloud of wooden shards. Sailors fell screaming as splinters pierced them. As Alastor watched, his friend Danyel covered his eyes with both hands, stumbling as blood leaked through his fingers.

The Laros rocked under a second impact, so jarring that Alastor nearly lost his grip on the rigging. Flames erupted, spreading across the deck like a liquid.

“Christ of Ophion,” Jax yelped. Alastor saw his fellow navior holding on by one hand, dangling twenty feet above the deck below. He reached out and grabbed Jax by his shirt, pulling him closer so he could double his grip.

“Captain, if we turn, we cannot engage,” Lieutenant Captain La Treille snapped. “Our orders—”

“We are two hundred yards from being at the outside of our range,” Salemon returned. “We’ll be fish food long before we cover the distance.”

Even Alastor, as green as he was, could see the truth in that. Every ship on their line had been hit, and several were sinking, while the Drehhu vessels remained untouched in the distance. Whatever demonic weapons they were using, they had a far greater range then the spear-flinging quilaines with which the Laros was armed. The fleet was being chewed to pieces, and they hadn’t yet fired a shot.

“They are demons,” Jax said.

“Come on,” Alastor said. “We’ve got to get the sails up.”

They were going against the wind, so they had dropped sail and put the rowers to work. The ship was turning, but very slowly.

“Ah, merde,” Jax said. “The captain’s put us broadside.”

The mainmast exploded in flame; what was left of it went up like a torch. The ship lurched as her babord side was slammed repeatedly by the invisible weapons of the Drehhu. La Treille twisted at the waist and kept turning, as his body tore apart and caught fire at the same time.

“We’re done,” Jax said. He groaned, and Alastor saw his friend had a splinter of the mast as long as an arm sticking out of his chest. Then Jax let go and plummeted to the flaming deck.

As the ship foundered, Alastor clung to the rigging. When it tipped to the side, he let go and fell into the sea. The Drehhu flames ran across the surface of the water. Swimming furiously as the fire swept toward him, he felt heavier with each stroke as the woolen clothing that had kept him warm during their cold passage to this battle became a sodden weight pulling him down. His breath rasped in his chest. His arms and legs stopped burning with exertion and began to grow numb for the chill in the water.

Alastor’s head dipped below the surface and salt stung his nose. If not for the many hours of his boyhood spent swimming, he would already be sunken in the gray depths. These were not the warm, sunny waters of the Coste de Sucre, however. He had escaped the fire, but even so he knew he didn’t have long to live.

He spied some floating wreckage and bore toward it, grasping with fingers he could no longer feel, and pulling his arms around it. It wasn’t much, not enough to pull himself fully out of the water, but it kept him afloat. He rested a moment, eyes closed, drawing in breath before opening them once more to look around.

* * *

IN THE distance, it looked as if the whole fleet was burning. Forty-five ships of war, turned to scrap in under an hour. Against all odds, a few had managed to come into range before succumbing to the enemy weapons, but so far as he could see, not one of the Drehhu vessels had been damaged. He was hardly surprised. They had no masts and were armored in metal.

The fleet of Ophion had never had a chance, here on the open sea.

The flames on the waves flickered and died away until only a few ghostly blue vapors remained. It was strangely beautiful, and then they too were gone, leaving only the iron-colored swells.

Another survivor began swimming his way.

“Do you mind?” the fellow asked, gasping as he drew near. He was a freckle-faced man with auburn hair.

“Come aboard,” Alastor said. “I’m Alastor Nevelon, from the Laros.” He helped the man find his grip on the flotsam and then waited for him to gather enough air to speak again.

“Henri Vallet,” the other navior finally said. “Late of the Delphis.”

“Charmed,” Alastor said. “With the two of us pushing this thing, we might be able to join up with that bit of debris over there.” He gestured.

“Ah, and have a proper boat,” Vallet said. “I’m for that.” They set out, kicking hard and navigating their piece of wreckage, and had some luck. Their prize was part of a mast that had some rope on it. It seemed like hours before they managed to lash together enough of a raft that they were able to draw themselves out of the water, and the overcast sky was little help in telling time. Once above the life-leaching sea they both sat silently, rubbing swollen hands. Alastor had torn out three nails, but didn’t feel it yet due to the cold.

“Where from, Nevelon?” Vallet asked, after a time.

“Mesembria,” he replied. “A place called Port Bellship.”

Vallet nodded. “On the Coste de Sucre. Nice little place.”

“And you?”

“Ophion Magne,” the man said. “From the city. Not the nice part of it, though.”

They fell silent. Other survivors could be seen, and more could be heard. Alastor turned his head slowly, surveying the horizon in all directions. The Drehhu ships were visible amongst the ruins of the center of the fleet, but none yet headed their way.

To the west, there was no horizon, only a strange grayness, like a wall of cloud.

“That’s it, isn’t it?”

“The Expiry,” Vallet confirmed.

“We never had a chance,” Alastor sighed. “What madness drove the admiral to this?”

“This wasn’t the plan,” Vallet said. “You must know that. The plan was to slip up into their port of Agath, and launch the assault in the harbor. We would have had twice their number, plus the advantage of surprise. That’s why we swung out so far—so close to the edge of the world—to avoid being noticed until we were there. But the Drehhu found out and met us here, with our backs to the Expiry, so we had no choice but to fight.”

“I hadn’t heard any of that,” Alastor said.

“Only the officers knew,” Vallet replied.

“You’re an officer?” Alastor stared at him. He wasn’t wearing a coat or hat. “Sir,” he added.

“Does it matter now?” Vallet said. “Shall I be captain of our little craft, for as long as it lasts? Be easy, Nevelon.” They fell silent for a time, then Vallet spoke. “Tell me about Port Bellship. Did you grow up there?”

Alastor nodded. “My family has a sugar plantation.”

“Really? And you chose to join the Navy rather than stay home and drink rum?”

“I thought I might see something of the world. Serve my emperor. Later, perhaps become a merchant sailor.” He glanced at the Expiry. He was certain now.

The current was taking them toward it.

Vallet noticed. “Yes,” he said, acknowledging the obvious. He didn’t sound afraid, or even worried. Just tired. “This is as close as I’ve ever been.”

“They say it cuts the world in half.”

“It runs from farthest north to farthest south, that much we know to be true,” Vallet said, “but whether or not the other half of the world lies beyond it, who can say?” He nodded toward the gray wall of mist that stretched as far as they could see in either direction. “No one who has ever crossed into that has ever come back. It might well be the edge of the world. It might be a wall between us and Hell.”

“I fear we shall find out,” Alastor said, although he also felt too exhausted to properly dread their fate.

Vallet glanced toward the Drehhu ships.

Two were moving in their direction.

“We know what the alternative is,” Vallet said. “If the Drehhu do not kill us, they will enslave us.”

Up ahead, from the direction of the Expiry, Alastor heard a single unholy shriek, followed quickly by another, then more, until there was a chorus of them.

“That doesn’t sound promising.”

The wall of mist loomed over them, filling their vision so that it was impossible to tell how distant it was, or how near. Not far off were four naviors on another makeshift raft. They vanished into it, and he expected to hear them scream, but there was no sound. A moment later he thought he heard something, but it might have been his imagination. The sky grew darker, and the approaching Drehhu ships became shadows in the distance.

They heard more shrieks of despair, and then other sounds—deep, stuttering clicks and weird, glissando wails, rising and falling in pitch from a high keening to tones so low he felt more than heard them. And a faint shushing, like an inconstant wind but also like distant whispering in an unknown language.

As full night came on, he thought he saw faint, shifting colors in the darkness.

“When will it happen?” Alastor asked.

“Perhaps we are already within,” Vallet replied.

“It does not feel different.” But even as he said it, he began to experience a prickling on his flesh, and his heart beat faster. It felt as something was shining on the side of him—the one that seemed to be facing the Expiry. A light his eyes could not perceive.

There was another strange noise: a grinding, churning sort of sound.

“Damn!” Vallet suddenly shouted. “Behind us.”

Alastor turned. He saw lights and the outline of a ship. A Drehhu ship. The awful noise was coming from it. A lantern of some sort turned toward them, and the beam fell on their makeshift raft. The enemy ship began to turn, then came directly toward them.

In that light, Alastor could see the Expiry, no more than ten yards away.

“We could swim,” he said. “Deny them their prize.”

“A slave can escape,” Vallet said. “He can escape and return to his home and drink rum in the evenings.” He nodded at the wall of mist. “From that, there is no return.”

Alastor nodded. He could see figures moving on the ship now. Not human. Bigger, with broader shoulders. They had four limbs like men, but those were long and spindly, and they made him think more of spiders than of people.

“A slave can escape,” Alastor agreed.

CHAPTER ONE

AMMOLITE

1009 E.N.

THE FIRST time Ammolite looked in a mirror, she was sixteen.

She vomited.

Ammolite was a slave. She did not remember her mother selling her, but Veulkh assured her that it had happened.

“A silver bar and a necklace of glass gems,” he informed her. “That was your price.”

Of course, that was after he began talking to her.

Her earliest memories were of wandering the opalescent, faintly glowing halls of his manse, of standing alone on stone balconies, traveling her gaze over the snow-covered peaks that surely held up the sky. Down the almost sheer rock face into which the manse was built, to the mysterious green valley far below. She left bits of food on the balcony for the birds, and over time some would take their treats from her fingers. She fancied they were her friends and gave them names.

A woman came each day to feed her, read to her, and later teach her to read, but Ammolite never knew her name. No sentiment developed between them. The woman did her job, and hardly spoke a word to her that was not written in a book. Once Ammolite could read passably, the woman showed her the library, and thereafter did not come again.

A new woman brought her meals and did not speak at all. None of the other servants talked to her, either, and she came to realize that some of them were not even capable of speech.

She read and she stared from the balconies, moving through her world almost like a ghost, and though she knew she had a master—and that his name was Veulkh—she never saw him.

Until, one day, she did.

* * *

MOUNTED ON a wall in her room was a calendar, a round mechanical thing of brass and crystal that counted off the days of her life. Once she came to understand it, she knew on a given day that she was—for instance—six years and seventy-five days of age. She did not often consult it, for each day was like any other, and the number of them hardly seemed to matter.

But one morning the calendar, clicking along as usual, suddenly belled a single, beautiful tone. She was awake already, and she stared at the device in astonishment. This was something different, something that had never happened before. It filled her with an unexpected sense of hope and anticipation.

She was exactly sixteen years old.

Before she could rise and dress, a small, hunched woman she had never seen before entered the room, bearing a gown of black silk.

“You will wear this,” the woman said.

The gown had unfamiliar fastenings but the woman helped her put it on. Up until then, Ammolite’s clothing had been simple shifts she pulled on over her head, so she did not know much about clothes, but the dress seemed far too big for her. It piled on the floor and tried to slip from her shoulders. She felt lost in it.

Then the woman led her through the manor into halls she had never seen, to a room with a table large enough to accommodate twice a dozen people but which was set with only two places. At one of these places sat Veulkh.

She was a little surprised at how young he looked. She knew he was a sorcerer, and from her reading she knew that it took many years to become a master of those arts. From some of the things she had overheard the servants say, she thought he must be very old indeed, but his dark hair and beard lacked any hint of silver, and his face was handsome and young.

And yet she still did not like to look upon it. There was something there that bothered her.

The woman led her to her seat. Like the dress, it seemed too large.

“Ammolite,” he said, absently. She wasn’t sure he was speaking to her at first, but then he faced her directly. Though his features were composed, almost serene, his eyes were peculiar, as if he was looking beyond or perhaps into her.

The woman brought each of them a glass of something red.

“I named you that,” Veulkh said, sipping at the red liquid. “Ammolite.” Unsure what to do, she took her glass and tasted its contents. It was strange and harsh, like fruit juice but with something a little spoiled in it.

When she did not say anything, he crooked a finger at her.

“You may speak,” he said.

“I did not know you named me,” she said.

“You had another name, before I purchased you,” he said. “I don’t remember what it was.” He smiled. “It hardly matters, does it?”

“I suppose not, Master,” she replied.

He took another drink of the red stuff.

“This is called wine,” he told her. “Vin in the language of Ophion. Nawash, in Modjal. It has other names. It is made from grapes.”

“Is it made by magic?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said. “A kind of alchemy is involved.”

She took another tentative swallow. It still didn’t taste good.

“I mentioned Ophion and Modjal,” he said. “Do you know what I was referring to?”

“Ophion is an empire,” she said. “Its capital is named Ophion Magne. It is said that a god by that name died and was buried there. They have an emperor and a council of savants. They are famous for textiles—”

“And Modjal?”

“Another empire, southeast of Ophion. Also with a capital of the same name, also said to be the resting place of an ancient god. Their emperor is known as the Qho—”

“Very good,” he said. “You’ve been reading the books I provided you.”

“Yes, Master.”

He nodded approvingly.

“Do you understand, Ammolite, what it is to be a slave?”

“It means that you own me,” she replied.

“That is correct,” Veulkh said. “Like this wine, and the glass it is poured in. If I wish to hurl it against the wall and shatter it, that is entirely my decision. The glass and the wine have no say in the matter.”

“I understand, Master.”

He drained the rest of his drink in a single gulp and then cocked his arm back to dash it against the wall—but then he smiled and settled the glass back on the table. The woman came to refill it from a crystal pitcher.

“Have you ever wondered why you are here?”

She had, but she did not say so. She shook her head and drank a little more of the wine.

“You are here,” he said, “as any slave is, because there are one or more tasks I require of you.”

“I understand, Master,” she said, “but I do not know what they are.”

“Finish your wine, and I will show you,” he said.

He watched in silence as she drank. It became easier as she went along. A sort of warmth crept over her, and her nervousness began to fade.

There is magic in this, she thought.

She wished he would talk more. She liked being spoken to.

“I’ve read about Velesa, as well,” she attempted. “That is where we are, isn’t it?”

“Who told you that?” he asked, a bit sharply.

“No one,” she said, “but your books are mostly in the language of Velesa, and your servants speak it—and that nation is known for high mountains.”

“You’re quite certain none of my servants mentioned it?”

“I’m certain, Master.”

“Well, you are mistaken,” he said. “That is not where we are.” He settled back, but a little frown remained on his face. He gestured for her to finish the wine. When she was done, he signaled to the woman, who left the room. Then he stood.

“Come, Ammolite,” he said.

She followed him, feeling a bit sluggish and clumsy. Her head was a little whirly. He led her through a door and into a room furnished mostly in red, and sat her upon a large bed. Then he knelt before her and took her hands. It was such a shock her first instinct was to pull away—hardly anyone had ever touched her, and she never touched anyone. She didn’t like it. His fingers felt warm, even hot, but they were gentle, and so she tried to breathe slowly, to bear it until it was over.

He placed her palms on his temples.

“Close your eyes,” he said. “Look. See her.”

She didn’t know what he meant, but she closed her eyes. At first she saw nothing other than darkness, the backs of her eyelids, but gradually something appeared, a mist, a light.

The light became a face, a woman’s face. She had dark eyes and pale skin, and her hair was as black as smoke. She trembled; it felt like a thousand insects were crawling upon her skin—and under it.

“There,” he said. “Open your eyes.”

She did so and found herself staring into his face.

“Orra,” he murmured. His eyes had changed. They seemed more alive, full of some barely contained emotion. As she stared, he began to weep.

“You must say you love me,” he said.

“I-I, l-love you,” she stammered, suddenly more afraid than ever. Then he pushed his lips onto hers. She felt a rush of claustrophobia, as if she couldn’t move her limbs, and tried to shove him away. Her body felt… bigger. Different. Not hers, somehow.

“You must say I please you,” he said. “You must.”

He was touching her now, touching her everywhere. His fingers were still gentle, but she wanted to scream, to get away.

“I have waited so long, Orra,” he whispered into her ear. “You’ve been gone so long, but I kept you, kept you…” He put his lips on her again, rougher this time, and on her neck and chest. He pressed her back on the bed as he pushed up her dress.

* * *

WHEN IT was over, she still did not know what had happened, but she was sore and sick. She cried, but he kept speaking to her, telling her to say she loved him and how pleased she was. It was almost as if he was begging, and so she did, through the sobs.

“You don’t understand, do you?”

“No.”

“Go there.” He pointed. “Turn the mirror around.”

She did so, happy to be out of the bed, away from him. He had pointed at a wooden frame, mounted on a swivel. She had read about mirrors, had caught faint glimpses of herself in water basins and the polished marble in some of the halls, but had never seen one. She turned the frame.

Ammolite had milky hair, and a small, narrow face. She thought her eyes were pale blue or maybe even white, but what she saw in the mirror was the woman with the black hair. The dress was not loose on her; she filled it with all the curves of the grown women who had attended her. When Ammolite moved her hand, the dark-tressed woman in the glass did the same.

And then she vomited.

Over on the bed, Veulkh laughed at her.

When she was done, trembling, she looked back up at the mirror, and the woman was gone, replaced by a sixteen-year-old girl in a dress far too large for her.

I want to die, she thought.

It would not be the last time.

* * *

SHE DIDN’T know the word for what had happened to her, and there was no one to tell her. The books in the library contained information on a wide variety of subjects, but nothing concerning what that thing was and why he put it in her.

As the calendar in her room ticked by her days and her birthdays—seventeen, eighteen, nineteen, twenty—she came to endure it. She became better and better at saying the things he wanted her to say, in the tone of voice he wanted. She learned to make it go more quickly.

In time, he stopped instructing her entirely, but instead gazed at her as if she were the only thing in the world that mattered. He told her again and again how he loved her, but she did not really know what that meant. She finally found a book that described the forms of “love.” One of them—eros—seemed to involve the things he did to her body with his. Another sort of love—pragma—seemed to explain the way he behaved after he was done with that.

It was in those moments that he spoke to her of things he and Orra had shared, long ago, the countries they had visited, places he would take her again. She realized that, in Veulkh’s mind, she had become two entirely different people—Ammolite and Orra. Sometimes she feared the same separation was happening in her own mind.

As Ammolite she could not bear his touch. It was easier to pretend she was Orra when he took her to the bed.

Except for one thing.

Orra—whoever and whenever she was—must have loved him as he loved her. Ammolite had only the mistiest notion of what love might be, but she knew she did not love Veulkh. She was, in fact, not even fond of him, as the books described it, no matter how embarrassingly sincere his pledges of devotion to her were.

There was another change, as well, and she took full advantage of it. Each night she was Orra and slept in his chambers, but by day—as Ammolite—she could go where she wished within the seemingly endless manse.

Besides the bedroom and dining room, Veulkh’s suite contained a kitchen with a balcony and a view of the mountains. Adjoining it was a steam room and bath tiled in turquoise and polished red coral depicting dolphins and sea serpents. What interested her most, however, was the spiral stair that led upward. Treading it, she discovered Veulkh’s library, which made for much more interesting reading than her own.

There were tomes on alchemy and thaumaturgy, venoms and vitriol, the humors of the universe and the human body, the atomies that dwell in living blood. Many of the books concerned weather and the nature of it, and of the world, its mountains and rivers and seas. Then there were the volumes written in scripts she could not read, but whose illustrations suggested they might be books of spells.

The first time Veulkh discovered her in the library, she thought she might be punished, but he hardly seemed to notice her. As she had once felt like a ghost, she had now become a ghost to him, for when she was Ammolite he hardly seemed to notice her at all.

One day, not long after her twentieth birthday, she decided to see how invisible she truly was, to discover if she could find the exit from the manse and simply walk away.

But if there was a way out, she never found it.

So she continued her self-education. She tried to prise out the meanings of the cryptic symbols in the spellbooks. She searched for some explanation of how Veulkh changed her into Orra, but found nothing except that transformation was one of the most difficult and dangerous of magicks.

* * *

IT TOOK her two years to find the book, the thing for which she had been looking without knowing exactly what she was seeking. By that time, she had taught herself a pair of the obscure languages in which many of the texts were written. It was a treatise on synapses, the locations where the powers of the world crossed or converged. The most powerful were natural, but they could also be created.

Soon after her first night with him, Veulkh took her to see his conjury, where he did his most powerful magics. She was certain it was one such synapse.

From the book she learned of another sort of synapsis, one each sorcerer fashioned for themselves. It was sometimes referred to as a “heart” or “core,” and was something like a key used to unlock the other powers of the world, an intermediary between will and practice.

That heart was also a vulnerability, for once it had been made, the sorcerer could not survive without it.

If she could find Veulkh’s heart…

She hardly dared think it at first. The book didn’t describe what such a thing would look like, but a few weeks after reading the book, she began to search. Carefully.

Veulkh’s conjury was above the library, a vast space carved deep into the living stone of the mountain, but with one face open to the wind. The floor was concave, and so smooth that she nearly slipped the first time she set foot upon it. Besides the stairway entrance there were two additional portals—one quite large, the other of a size with those throughout the manse. Both were always locked.

Sometimes she watched him work. It was never the same twice. At times he surrounded himself with dark fumes and sang in a guttural language. On other occasions, he drank potions, traced symbols on the floor, or sketched them in the air with a burning wand. Sometimes he made no preparation other than to walk to the center of the room and stand silently.

Whatever his behavior, the hair pricked up on the nape of her neck and she felt strange tastes in the back of her throat. Light and color became weird, and faint noises sounded within her skull. It frightened her, but she was also strangely drawn to it.

She also began to see what it did to him, how each time afterward he was both more and less than he had been before. Sometimes he lay in a daze, neither truly awake nor asleep, twitching at things she did not see. When this happened, however, Kos, the captain of his ravens, was always near, along with four or five other guards. The ravens dressed in red, umber, and black-checked doublets and were armed with sword and dagger.

They were not slaves. He paid them in gold.

At times the stairwell door was locked. On many of the occasions when he was rendered weak, she could not see what he did. On those days, the very stone of the mountain shook, as if thunder had been loosed inside of it. At first it had alarmed her, but eventually she learned to accept it as a natural way of things.

“Why do you do it?” she asked him one night, when she wore Orra’s face. She had drunk more wine than usual and felt talkative.

“Because I can,” he replied. For a moment, she wasn’t sure he knew what she was asking, but then he rolled on his side and looked her in the eyes. “Princes beg for my services,” he said. “Emperors fling gold at my feet, and yet I am beholden to no one.”

“What of the Cryptarchia?” she asked.

An expression of impatience began to inform his features. “What do you know of the Cryptarchia?” he asked.

“That it’s something like a guild,” she replied. “A sorcerous guild.”

“That clucking bunch of hens.” He sighed. “I condescend to follow their rubrics when it suits me, but I long ago rose above them. I am my own. The cryptarchs—politicians, librarians, and their strigas-sniffing bitches. It can hardly be named sorcery, what they practice. There are very few of my kind, Orra. I am one of the last.”

“But there are others?”

“A few,” he replied. “None so powerful as me. And now we shall speak no more of this.”

She knew his moods, and so pressed no further. For several months things went on as they always had.

Then the calendar struck her twenty-first birthday.

CHAPTER TWO

CHRYSANTHE

COSTE DE SUCRE, MESEMBRIA

1014 E.N.

CHRYSANTHE KNEW Lucien was going to kiss her.

A zephyr soughed through the sugar cane fields that rolled to the right and down from the hilltop path, stirring the curls of her golden hair. A flamboyance of flamingos rose through a saffron haze, drawing their silhouettes across the cinnamon and indigo clouds mounded on the horizon. Pale green sprites flitted in the jagged fronds of the palm forest bordering the left side of the trail. The hem of her periwinkle gown brushed softly against the grass.

It seemed as if all the world was in a state of pleasant agitation.

And then they stopped walking.

Lucien was taller, so he had to bend. It gave her time to turn her face, so his lips landed on her cheek. He paused for a moment, his brown eyes peering uncertainly, and then abruptly straightened.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I suppose I wasn’t thinking.”

“I suspect you were doing a great deal of thinking.”

She smiled, to soften it.

He folded his arms.

“It’s just, the time we’ve spent together—when you asked me to escort you…”

“But I didn’t, Lucien,” she said. “You asked to accompany me. By the gate, as I was leaving.”

A little furrow appeared on his forehead, and she thought again how handsome he was—pretty, almost, with his high cheekbones and aquiline nose. Although he was only twenty-five years of age, the line of his cinnamon hair was already receding from his brow, yet it lent him some needed gravity. As always, he was dressed fashionably—today in a canary shirt, a cravat of fawn ribbon, and a redingote of the same color. He held in his hands a small-brimmed bicorn hat.

“Yes,” he said. “I suppose that’s true—but really, how could I allow a lady to go solitary into the countryside?”

“You are gallant,” she said, “and I am happy to have your company. Only… behave.”

Lucien smiled: nervously, she thought. He was an entirely affable character, intelligent and well-read. She enjoyed their conversations. Of good birth, he was lately from distant, fabulous Ophion, an investor in her father’s enterprises on an extended stay to learn how the sugar business was run. Quite different from the local characters who called on her.

A breath of fresh air, at least at first. And her mother adored him, with her eye always turned toward noble connections to lift the family from its mercantile roots.

Chrysanthe turned from the large path onto a smaller one that wound off through the palms.

“It is getting late,” Lucien said. “The sun is nearly gone under. Perhaps we should turn back.”

“Only a little further,” she said. “It’s been a long time since I’ve come this way. There’s an old chapel just ahead. It’s quite beautiful, especially at dusk.”

“A proper chapel, you mean, or some old native collection of rocks?”

“Well, you can judge it for yourself.”

They walked a few more paces.

“This seems like a dreadful idea,” he said as they moved further from the fields and into the thickening forest. “We might become lost. Or some wild animal—”

“You have your sword, don’t you?” she said. “You can defend me if need be, can you not?”

“Well, yes.”

“And as for becoming lost—look, this is a well-worn trail. More so than I remember it, really. Last I came here it was quite overgrown.”

“Still. I will have to answer to your mother if I keep you out after dark.”

“A spring dampens the path here,” she warned. “Take care, the ground is slippery.” She took her own advice, stepping carefully through the slick white clay. The chapel rose ahead, caught in a low beam of westering light that sifted through the trees. She found a pleasant view and stopped to admire it, leaning against the husky bole of a palm.

Even in its age and disrepair she thought the chapel was beautiful. Built of white stone, its every surface was figured with serpents, flowers, dancing figures, and symbols of air and night.

“Lovely, isn’t it?” she said. “In their day, the Tamanja built magnificent things. Before the Drehhu destroyed their civilization.”

“There’s not so much to them now,” Lucien said. “Passable laborers, but of little use in any higher capacity. They are lucky to have our protection.”

“Yes,” she said. “Our protection.”

“I admit, though, that it’s a fetching sight,” Lucien said. “May I now escort you home?”

“You know,” Chrysanthe said, “there is a ghost here. If you stand just in this place, sometimes she makes herself known.” She took a few steps toward the chapel and then stopped. Took a deep, slow breath as Lucien joined her. “You feel that?” she whispered. “Like water running across your face?”

“I—yes!” Lucien said. “That is quite amazing.”

Chrysanthe smiled. She had been only eight when she discovered the ghost.

“Close your eyes,” she said, shutting hers. For a moment, there was nothing but darkness, but then a face formed, a girl’s face with broad cheekbones and green eyes.

Mah simki? Simi Sasani, a voice murmured.

“Oh!” Lucien said. Chrysanthe opened her eyes and saw that he had jumped back a yard.

“Were you startled?” she asked. “I did warn you.”

“It’s just… your voice sounded so strange. Not like you at all.”

“Oh, did I speak?” Chrysanthe asked.

“Yes, in some strange language.”

“That was her,” she said. “The ghost. The language is an antique form of Tamanja. She asked my name and said hers was Lotus.”

“I did not hear a ghost speak, only you.”

She nodded. “I am sensitive to ghosts,” she replied. “I always have been, like my grandmother was. Parfait Hazhasa at the basilica says it’s not common, but not unheard of either.”

“I see.” Lucien nodded. “How terribly interesting. Now may I renew my offer to walk you home?” He still seemed agitated.

“That’s agreeable,” she said, and watched the relief spread on his face.

“Wait a moment,” she said. “Do you hear something?”

“Another ghost?” he asked.

“No. In the chapel.”

“No,” he replied. “Nothing.”

“Let’s have a look.”

“Chrysanthe!” he said sharply. “If someone is there, they might well be thieves or vagabonds.”

“Well, if so, they have no right to take up residence on my father’s estates,” she said. “You have your sword. We shall investigate.”

“You are far too rash,” he complained.

But he followed as she crept toward the chapel. The building’s base was oval, some forty feet in length, with an entrance on the east side. Before they had reached the opening, a man stepped out. He was a rough-looking fellow, dressed in worn cotton shirt and pants. His lips were bisected by a scar that resembled a white caterpillar when he closed his mouth. He had a short, heavy sword thrust in his belt.

He glared at the two of them.

“What is this?” he demanded.

“What are you doing in there?” she demanded. “I am Chrysanthe Nevelon. These are Nevelon holdings. Step aside, please.” Beside her, Lucien drew his sword.

“Do as she says.”

Reluctantly, the man moved away from the door. Chrysanthe approached the chapel and looked within. The fearful, wide-eyed gazes of some fifteen children looked back at her. They were dirty, clad in rags, and bound together by chains.

“Danesele!” one of them cried.

“Yes, Eram,” she said. “We shall have this all fixed, very soon.”

She turned back to Lucien, who now stood with the other man, facing her.

“Chrysanthe…” he began. His sword did not quite threaten her, but aimed at some point between her feet and his.

“I do not like coincidences, Lucien,” she told him. “True happenstance is vanishing rare. The children began disappearing soon after you arrived. I inquired about and discovered that you had made some odd purchases—chains, for instance—and I once noticed a bluish-black stain on your kerchief. It looked like ahzha, which is often used by slavers to pacify their victims.

“At times,” she continued, “you had on your coat a scent of burnt dung, which is what the villagers use for fuel. What business would you have in the villages? I wondered. In time, my only question became where you were keeping your prey until you could move them to the trade, and then I noticed the white clay on your boots. This is the only place I know of where that particular color of soil is present.

“And you.” She nodded at the other man. “I recognize you. You work for my father. How could you betray him so?”

Lucien looked terrified, his features working.

“Chrysanthe,” he said. “This all can be explained—”

“Yes,” she said. “The explanation is that you’re selling into slavery children under my father’s protection.”

“They are little better than slaves as it is,” he said, starting to look angry.

“That is not true,” she said. “They are paid wages, and they may not be purchased or sold.”

“Accidents happen,” the other man suddenly said. “There is a place, not far from here. Many crocodiles. She went out alone, she never comes back…”

Lucien pursed his lips and broke eye contact. He looked like a trapped civet.

“Lucien,” Chrysanthe said. “There are two reasons I did not let you kiss me. The first, I think you now know. The second reason is that if my brothers saw you taking such liberties with me, they might kill you.”

“Your brothers?” he said. “They were not there.”

“Oh, Lucien,” she said. “Of course they were.”

Lucien paled and turned as her eldest brother Tycho emerged from the trees. At twenty-four he was six years her senior, as brown-skinned as their father. Like her, his hair fell in curls to his shoulders, although in his case the locks were almost ebony. He wore a hunting jacket and broad-brimmed straw hat that stood in marked contrast to Lucien’s finery.

“Another of your games played out, sister?”

Upon his arrival, Lucien’s partner in crime suddenly bolted toward the jungle deeps, only to be arrested at sword-point by Gabrien, the next eldest, his cropped red-gold hair like a mirror of the drowning sun. He had their mother’s thin, fine nose, which along with his coloring—and certain behaviors—had earned him the nickname Li Goupil, or “the Fox.” Theron—the youngest at fifteen—came close behind, a bow and six arrows couched casually in one hand. Theron and Chrysanthe shared the same heart-shaped face, deep brown complexion, and blonde hair. Despite the age difference, people often thought them twins.

Lucien spun and sprang toward her, his expression fervid. She had almost been expecting something like that and had quietly slipped a bodkin into her hand, but her shoes were still slippery from the mud and she slid on the ancient limestone of the chapel. She dropped her knife and, before she could find her balance, Lucien grabbed her.

“Listen,” he cried. “I mean none of you any harm. I only intended to earn a bit of profit.”

“You took a walk off that road,” Tycho said, “when you put hands on my sister.” He laid his hand on the grip of his saber.

“Stepping into a big crack,” Theron confirmed, laying an arrow on his bowstring.

“Maybe we should visit those oh-so-convenient crocodiles,” Gabrien suggested.

“No, listen,” Lucien pleaded, desperately. His sword was at her throat; she could feel the edge nicking her. “You three back off. I only want to reach the emperor’s consul and assure my survival from you… barbarians.”

“All of this sweet talk,” Gabrien said. “You’re right, Santh, quite a romantic fellow.”

“Lucien,” Chrysanthe said. “Listen to me quite carefully. The penalty for kidnapping children is something your family will be able to pay off, in time, but if you hurt me—Lord forbid that you should kill me—there will be no court for you. You will be hacked to pieces, and your head put on a spike so the vultures can peck it to the bone.”

He seemed to sag, but the sword did not waver.

“They will kill me anyway,” he said. He was weeping.

“I will ask them not to.”

He tightened his grip. “Why should…?” he began, but then a hand appeared in front of her face, coming from behind. It grabbed the blade at her throat and pushed it away. Lucien yelped and let her go. She stumbled back against the chapel as someone slammed Lucien to the ground, following him down.

No, not someone. Two men, in the sable-and-aubergine uniforms of the Emperor’s Navy. Lucien tried to fight back to his feet, but one of the men dealt him a terrific blow to the chin. The other fellow picked himself up and stood aside, throwing her a concerned look with his wide blue eyes.

“Crespin!” she shouted. “Oh, Crespin!”

Her brother’s companion, a lanky fellow with unruly brown hair spilling from beneath a seaman’s cap, kicked Lucien in the ribs.

“Miserable excuse for a dog!” he shouted. “Shit from a bastard hyena…”

“Renost!” she cautioned. “Do not kill him.”

Renost kicked the man again. “I’m not your brother,” he said. “I’m not bound by your request.”

“We need him, Renost,” she insisted. “To find the other children.”

Renost stood there, panting heavily for a moment, his black eyes blazing. Then he nodded.

“But for the grace of her,” he told the moaning Lucien, then he spit on him. Crespin had reached her by then, and she threw her arms around him.

“We were bringing you a little surprise when Theron reported that you had wandered off with this fellow,” Tycho said, nodding at Lucien. “I suppose it’s a bit more of a surprise now.”

“It is,” she said. “Of course it is. A wonderful surprise. Crespin, I thought you had another year at sea before we would see you again. And you, Renost…”

She suddenly realized Renost was bleeding heavily from one hand. It must have been he who had grabbed Lucien’s sword.

“That?” he grunted, noticing her attention. “Just a nick.” Then his eyes went wide, and he fumbled to remove his hat. “Danesele,” he said.

“Travel has made you more presentable, Renost,” she said, “but formal address is unnecessary. Despite your protests, you are as much a brother to me as these others.” It was then she noticed a third fellow in the emperor’s colors, a nice-looking young man with straw-colored hair watching everything with what she took to be surprised amusement.

“Sir,” she said, nodding.

“Oh, sister,” Crespin said. “I am remiss. This is our companion, the most excellent seigneur Hector de la Forest, our ship’s surgeon. He came ashore with us at our urging, so he might see for himself that our country is not so savage as he has heard.”

“I am most pleased to meet you,” Forest said, making a little bow. “And to you, Crespin, I must apologize for my former opinion. Not a jot of savagery to be seen here. But perhaps our friend Renost could use a bit of aid?”

Renost shrugged. Blood continued to pour from his hand.

“Really,” Chrysanthe said. “Let’s wrap that up.” She ran her gaze over the whimpering, supine form of Lucien, and his accomplice, who—despite his sun-darkened face—seemed as pale as a cotton boll.

“Unchain these children,” she told him.

“Yes, lady,” he said.

“Theron,” Tycho said, “fetch the horses.” He turned to Chrysanthe. “We’ll see to them,” he said. “Crespin and Renost will escort you back home.” She checked an objection—she wanted to see the children returned, but who knew how long Crespin would be in port.

“Thank you, Tycho,” she said. “And you two,” she added to Theron and Gabrien. “Where would I be without you?”

“Crocodile food, I reckon,” Gabrien said.

* * *

NIGHT FELL softly, stirred by warm winds fragrant with the perfumes of orchids and water lilies. Beyond the terrace, fireflies danced above the swollen waters of the Laham River as bright Hesperus set into the trees and lesser stars brightened. A night bird trilled, accompanied by the strains of a harp. Chrysanthe glanced over at Forest, who was gazing out over the river.

“I’m sorry for your rude introduction to our country, seigneur de la Forest.”

“Eye-opening to be sure,” he said, “but I’ve spent some time in company with your brother, so these events are perhaps not so surprising.” He swept his glass around. “And this is all so lovely,” he said. “You are all so gracious to invite me to your home.”

“Where do you call home, seigneur?”

“Please, call me Hector,” he replied. “My home is a little-known place, I’m afraid. Poluulos.”

“The island in the Mesogeios Sea?” she said. “Known for its excellent timber?”

“You astonish me,” Forest said. He looked over at Crespin. “Your sister astonishes me.”

“Oh, yes,” Crespin said. “We are all quite astonished.”

Forest looked back to her and nodded. “Yes, that is indeed the place. In fact, its timber was once so excellent that, at present, not a single tree remains on that little rock.”

“That, I was not aware of,” Chrysanthe said.

Hector spread his hands. “Well,” he said, “the timber is gone, but we still have young boys in plenty to grow up and go into the emperor’s service, and so here I am, in this very excellent company. Tell me, Danesele, is your life always so exciting as it was today?”

“Yes,” Renost answered. “Because she makes it so.”

“Exactly,” Crespin said. “You realize, Chrysanthe, that eventually one these escapades of yours will end… badly.”

“It did end badly, for Lucien,” Tycho pointed out, taking his seat. He had traded his hunting attire for a zawb, the loose linen robe favored by the native Tamanja. The younger boys were still cleaning up.

“I mean for her,” Crespin said. “And she knows it.”

“I cannot stand idly by while my father is robbed or his reputation compromised,” she protested.

“Tycho is in charge when Father is away,” Crespin replied. “He is fully capable of seeing after the business. It’s not like when were children, pretending to be agents of the empire—”

“Remember that secret language you two used to scribble in?” Renost said.

“It wasn’t a language,” Chrysanthe said. “It was a cypher.” She shot a mock frown at her brother. “Did you come all and across the sea just to lecture me, dear brother?”

Crespin spread his hands. “The lecture is done,” he said. “I only urge you to exercise some sense.”

“Like you, I suppose?” she said. “Renost, Hector, tell me truthfully. Has my brother stayed clear of trouble during his time in the Navy?”

Renost grinned. “Well, that all depends on what you mean by trouble.”

“Renost!” Crespin said.

“Is it trouble, for instance, to offend the Veil of Codaey by offering his daughter inappropriate gifts?”

“Flowers!” Crespin protested.

“Red jonquines, to be particular,” Renost said. “They have a very specific symbolism in Codaey. Shall I explain?”

“No need,” Chrysanthe said hastily, glancing at her younger sister Phoebe, whom she found gazing at Renost with adoring eyes. When the girl noticed Chrysanthe watching her, she quickly returned her regard back to her harp strings.

“I was innocent of their meaning,” Crespin alleged.

“Was it trouble to climb upon the roof of the holy sepulcher of Phejen?” Renost went on. “Trouble only for the city watch, who pursued him throughout the town for the better part of the night.”

“Us,” Crespin amended, waving a finger between them. “Pursued us.”

Renost raised his wine. “Well,” he allowed, “It was an excellent view.” The two men clinked their glasses together.

“I see,” Chrysanthe said. “So I’m to be advised against a little housecleaning, while you two leave every port in shambles?”

Crespin frowned. “Is this true?” he asked Renost. “Every port?”

“No,” Hector said. “The two of you left Isle Saint in good order. Hardly touched.”

“There,” Crespin said. “You overstate the case, sister.”

“Trop, enough!” Chrysanthe said. “No more of your mishaps, but tell me this—what happy chance brings you home to us early?”

Crespin’s squared features settled into more serious lines. “The same turn of fate that will bring Father back home tomorrow, or the next.”

The harp stopped abruptly.

“Father returns?” Phoebe gasped.

“He does,” Crespin replied.

“We shall all be together, then!” Phoebe said joyfully. At fifteen, her capacity for mercurial elation—and misery—seemed boundless.

“For a time,” Crespin said.

Chrysanthe felt a sudden worry creep into her ear and down to her throat.

“What is it, Crespin?”

“War,” he replied. “We are going to war.”

Silence fell for a moment. Chrysanthe was considering what to say when the door burst open behind her.

“Chrysanthe!” her mother bellowed. “What have you done?”

CHAPTER THREE

HOUND

THE VALLEY OF ELMEKIJE

1014 E.N.

AS HE watched the baron’s horsemen gallop down below, Hound was suddenly sorry he’d done such a good job in laying the false trail. They had fallen for it and were going the wrong way—the chase was over before it had begun. The idiots were only yards away, but they would never see him, hidden as he was in the leafy stand of hog-laurels.

That can be fixed, he thought.

With a wild shout, he bounded down the hill and flung himself at the rearmost horseman. With the back of his tomahawk, he rang the fellow’s helmet like a bell. Before the rider had toppled from his saddle and slammed heavily to earth, Hound was already hurtling up the hill on the other side of the path.

“He’s there!” one of the men shouted.

Belatedly a few arrows hissed through the oaks, none very close to him. He whooped mockingly as he once again vanished from their sight, then chuckled at the litany of curses that followed. Running along the ridge top for a few paces, he descended into the next valley in long leaps that sent him skidding on leaf mold. It felt almost as if he was flying. The curses were still there, and the crashing of horses and armored men through the undergrowth.

Hound was not so encumbered—he wore nothing but a loincloth and a belt that supported his small ax and a bag of smooth stones.

He vaulted over the stream at the base of the valley, ran a few more steps, and then stopped in front of a wall of thorny briars. Putting his ax back in his belt, he took one of the pebbles from his bag and appraised it before uncoiling the sling from his wrist. Then he fitted the stone into the elk-hide pocket.

The men came down the hill now. One of them, named Detel—a burly fellow with red hair—spotted him.

“Shoot!” Detel bellowed. A few more arrows came his way, this time with better aim, and Hound stepped behind a sweetgum.

“You little piece of govno,” Detel shouted. “Today is the end of you.”

“Well, everyone has their day,” Hound yelled back. He stuck his head out from behind the trunk. “But tell me—what are you fellows so mad about?” He ducked back as a feathered shaft thunked into the tree.

“Trespass in my lord’s forest,” the man responded. “Every kind of petty thievery. Vandalism. Witchery. Chicken stealing—”

“I think you covered chickens under petty thievery,” Hound shot back. “Yes?”

“Get him!” Detel roared.

Hound took the time to pick out the best of the archers. Whirling his sling, he stepped from behind the tree. The man wore a helmet with a nose guard, so Hound sent the missile into his unprotected throat. Then he flung himself into the briars, dropping down on hands and knees to scuttle along the slightly less congested forest floor.

He emerged from the thorns at the edge of a cliff which dropped about twice the height of his body down to a beaver pond. He jumped and hit the deepest part. Surfacing, he swam to shore. From there, he turned east and began to work his way back behind his pursuers, reckoning there might be some fun yet to be had with them.

He checked the sky, saw a raven circling, and smiled.

Climbing a huge magnolia, he perched in the upper branches and watched the first of the baron’s knights hack his way through the briars, lose his balance, and topple into the beaver pond. Another man emerged: Hound gauged the distance. They were just at the edge of his range, so chances were another stone would only alert them to his location. Which might be fun—starting the chase up again—but probably wouldn’t be. Better he return to Grandmother to tell her what he had seen.

He was starting down the almost ladder-like arrangement of limbs when he heard a twig snap. Looking down, he found himself facing the point of an arrow on a drawn bow. Wielding the bow was a lean man with surprisingly blue eyes and not much hair. He stood in a copse of fern trees nearly as tall as he was. A pack rested on the ground not far from his feet.