Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Icon Books

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

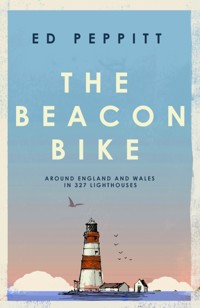

The incredible story of a 3,500-mile cycle ride to explore the onshore and offshore lighthouses around the coastline of England and Wales, proving that a diagnosis of Multiple Sclerosis doesn't mean giving up on a lifelong dream. The Beacon Bike is the inspirational tale of one man's quest to fulfil the promise he made to himself as a small child, nestled in the bed of an attic room while the glow of Dungeness lighthouse flashed past his window - a comforting, ever-present companion. It is also a loving tribute to the coast; not only its beautiful landscape, but also the communities that make it so special. It celebrates the generosity of spirit found in people around the the country, as well as the history of the iconic lights that brighten their world. This journey is a testament to the joy of life's simple pleasures. A warm welcome at the end of a long day. The fire of a child's imagination, rekindled in later life. The power of a light that pierces the darkness.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 486

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in the UK and USA in 2024 by

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

39–41 North Road, London N7 9DP

email: [email protected]

www.iconbooks.com

ISBN: 978-1-83773-168-8

ebook: 978-1-83773-169-5

Text copyright © 2024 Edward Peppitt

Images courtesy of Adrian Burrows

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typesetting by SJmagic DESIGN SERVICES, India

Printed and bound in the UK

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Prologue

Week 1

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 6

Week 7

Week 8

Week 9

Week 10

Week 11

Week 12

Week 13

Week 14

Postscript

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I should really start by thanking Derrick Jackson, the author of Lighthouses of England and Wales, who is entirely responsible for my interest and love of everything lighthouse-related.

My cycling adventure would not have been possible without the help of George Pepper and the wonderfully supportive team at Shift.ms that he has established. Thank you all. If you or anyone you know is diagnosed with MS, then Shift.ms should be your first call.

I’m also indebted to the Association of Lighthouse Keepers for their help in planning my route, supporting me along the way, and hooking me up with members to meet, former keepers to talk to, and beds to sleep in. The Association has become my second family, and I am grateful to you all.

I am very grateful to Robert Gwyn Palmer, who helped me to secure so many valuable connections, including that feature in the weekend Telegraph.

I owe heartfelt thanks to anyone who followed my progress, sent messages of support or donated to Shift.ms. So many times I would have given up without your encouragement.

I was extraordinarily lucky to meet Phil Sorrell, a fellow MSer, who set me up with a brilliant application that plotted my live location on my website map every step of the way. Thank you, Phil. You helped my followers feel so much more connected to my daily progress.

I would like to thank all my followers on social media, but James Sharp in particular, my most prolific and loyal Twitter follower by a distance. I am also indebted to my friend Paul Uttley, whose generosity ensured I could complete the expedition.

With the cycling behind me, so many others helped me in the making of this book:

Thank you, Karena, for convincing me that it was worth writing, as well as for helping me get started. Thank you, Jo, for the ongoing encouragement and for improving my writing in every chapter.

My friend Adrian deserves eternal praise and glory for the time and patience he took to illustrate every one of the 327 lighthouses I saw.

Thank you to my agent, Tom Cull, for agreeing to represent me and finding the perfect home for The Beacon Bike. You are the real deal.

And thank you to Connor Stait and the team at Icon Books, for making the magic happen.

That only leaves arguably the two most influential people who have helped turn a childhood dream into reality …

Allan, my wingman, who was there at the start and again at the finish line, who was ready to travel to Ilfracombe, Lundy, Clevedon, Carlisle, Berwick and Dungeness to make sure I stayed on course.

Lastly, and most of all, my thanks to my long-suffering wife, Emily, for encouraging me to make the journey, tolerating my sabbatical from parental duties, and for her patience, support and kindness throughout.

PROLOGUE

Somewhere in the space between wakefulness and sleep, I become aware of the regular blink of light. It permeates the inky blue darkness and momentarily brightens the plain white walls. I begin to count the interval between flickers – always ten seconds – each flash illuminating the room, punctuating the dark reassuringly. I climb out of bed and make my way to the window, looking out to find the source. And then it comes to me. The light is travelling through the night from Dungeness, from the beacon that keeps ships from running aground and sailors safe, that marks the end of the land and the beginning of the sea. The lighthouse.

Seeing the light

When I was a child, a part of each school holiday was spent at my grandmother’s house on Romney Marsh in Kent, about half a mile from the sea. It was a house divided into two – she had bought a large town house after the war, then set about splitting it down the middle and selling one half to an old friend. The hallway had two unlocked doors, one to each side of the original house, where my grandmother and her friend met each morning to allocate the morning post. They even shared a party phone line between them, and you could often listen to Mrs Kemp’s tittle-tattle just by picking up the receiver. I had a bedroom in the eaves, and from the mullioned window I could see for miles around.

It was July 1974 when I made the discovery that it was the lighthouse that projected its flash onto my bedroom wall. I was just six years old. It felt comforting, reassuring somehow. Each day of our holidays on Romney Marsh, I climbed the stairs to my room at dusk to check that the light was still flashing. And I remember the sense of relief and wonder each time I saw it.

We had a routine for every holiday. There would be a trip to Dymchurch, dubbed ‘the children’s paradise’ and home to fish and chip shops, a funfair and the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch railway that ran along the coast from Hythe. We’d schedule a stop at Dungeness, and my dad would buy fish from the seafront shack run by Mrs Thomas. She’s still there today, although it is her son rather than her husband who brings in the catch, most of which is supplied direct to local restaurateurs. You have to be on the shore early and meet the boat to compete for the pick of the freshest fish.

Then we’d walk our Labrador, Sam, along the shingle beach, towards the pair of lighthouses. I discovered that the earlier 1904 lighthouse had been made redundant once the nuclear power station was built in the sixties, which obstructed its beam of light across the distinctive shingle spit. A new lighthouse had to be built in 1961, unmanned and automated, and one of the last new lighthouses that Trinity House, the body that governs lighthouses in England and Wales, ever built.

On some trips, when the weather allowed, Dad would go night fishing with long lines, setting up his fishing paraphernalia, his flask and his lamp on the shingle at dusk. I sometimes joined him, but only in the hope that I might meet the lighthouse keeper arriving for his night duty. I imagined him with a large bunch of keys, immaculately dressed in smart Trinity House uniform and distinctive white-trimmed cap. With hindsight, he must have looked a lot like Captain Birdseye. But he never did arrive, a fact that mystified me, as come what may, the light would unfailingly start to flash as dusk approached.

That’s when my obsession with lighthouses began. My parents noticed, and presented me with a copy of Lighthouses of England and Wales by Derrick Jackson, a book that became my favourite companion for many years. I learned how, when and where they were built, and that every lighthouse has a unique character, with no two sharing the same light, colour and flashing pattern, so that mariners could distinguish one light from another.

I suppose I could have become just as obsessed with steam engines, toy cars, football, sticker albums or any other pastime that tended to attract boys of my age. But for me it was only ever lighthouses.

When I was ten or eleven, and enjoying some independence with the help of my bicycle, I formulated a plan for an adventure that one day I would undertake. I would cycle around the coast, clockwise from my grandmother’s house, ticking off each lighthouse that I’d read about obsessively in my book. I recently discovered five rusty-stapled pieces of paper in the back of a filing cabinet that outlined my proposed journey, how far I would cycle each day, which lights I would see and where I might stay.

It was an expedition I was confident that I would undertake one day, but, like many dreams or ambitions formed in childhood, life got in the way. It was always a trip that I planned to make one day soon. Nevertheless, lighthouses remained a constant feature of my life. I remember every family holiday not by the cottages we rented or the food we ate, but by the lighthouses that were nearby. Summers in the West Country meant Start Point, the Lizard or Tater Du on the south coast, and Hartland Point, Lynmouth Foreland or Trevose Head on the north coast. The August weather had been so poor over the summers of 1974 and 1975 that my parents decided to holiday inland in 1976. We rented a cottage in Kettlewell in the Yorkshire Dales and promptly sweated out the hottest, driest fortnight for 100 years. My mum assumed that my quietness during that holiday was because I was missing the beach and a bucket and spade. But I knew it was because there wasn’t a single lighthouse within 40 miles.

The summer holidays that followed Kettlewell were almost perfect for me. My aunt had bought a small cottage in Llanmadoc, on the Gower Peninsula in Wales, and we stayed there for three consecutive summers. From the cottage, I could walk to the ruined wrought-iron lighthouse at Whiteford Point, and rainy days meant Swansea Market followed by a glimpse of the lighthouse at Mumbles.

After university, I joined up with a number of other slightly rudderless would-be travellers by getting a job at Stanfords, the map and travel bookshop in Covent Garden in London. Here the staff were incredibly knowledgeable, but held a shared belief that they should be, and deserved to be, travelling somewhere. As a result the retail part of the job was never taken very seriously, and serving customers was always regarded as an unwelcome and somewhat disagreeable aspect of saving up for the next big trip.

Retail staff came, saved up their funds, went travelling and then returned to start the process all over again. I quickly learned the hierarchy: seasoned, global travellers worked upstairs on the international desk, sharing their stories of travelling through unmapped and politically unstable parts of the globe. Those with fewer expeditions under their belt worked at the European desk on the ground floor. From here, they were as likely to be called upon to help with the choice of gallery, restaurant or hotel on a romantic city break, as with possible places to camp on a long-distance trek across the Alps. That left me in the basement – a windowless, dark and rather damp space – selling local walking maps and guides to British towns and cities.

There were three of us in the basement. At one end of the floor sat John, a 30-something amateur sailor who ran the maritime department. His passion was for boats rather than retail, and he despised most of the customers he was called upon to serve. He reserved the strongest disdain for customers who asked questions, and also for those who took books or maps off his shelves, even if they subsequently purchased them. But he had one unrivalled skill that became his party piece. Describe a sailing or boat trip anywhere in British waters, and John could tell you which British Admiralty chart or charts you would need. From a catalogue extending to hundreds of pages, this was an impressive feat to witness.

At the other end of the floor was Jon without an h, in charge of all maps and books published by Ordnance Survey. Now, Jon had already clocked up twenty years of service at Stanfords, almost all of which had been served in the basement. He had exceptionally blond hair and pale skin, and I wondered if it was natural or had resulted from a lack of sunlight. He had an extraordinary memory, as well as a trick up his sleeve of his own. Name any village, town or city in the UK and Jon would know, instantly, which of the 250 or so large-scale Ordnance Survey walking maps it appeared on.

I took the central sales area of the basement, and my role covered general UK tour guides, street maps and road atlases. But I spent a lot of my day trying to appease or apologise to customers who’d had dramatic fallings out with John. On one occasion a customer approached my friend David at the international desk and asked for help with selecting an Admiralty chart. When David suggested that he needed to head down to the basement, the customer begged him to come with him, explaining that he ‘daren’t ask that ghastly man for help again!’.

I may have had some natural talent for retail, but I realised that I needed my own party trick if I was to hold my own in the basement. It came very quickly and easily to me. Name any point on the UK coast, and I could reel off the ten nearest lighthouses heading either clockwise or anti-clockwise. Admittedly, mine was the least valuable skill from a retail perspective and it was seldom called upon. But it was always something of which I was immensely proud.

Stanfords was also where I met my wife, Emily. It’s fair to say that she has endured, rather than embraced, my passion for lighthouses, but she has always been supportive of my slightly quirky interest, nonetheless. She once arranged a surprise holiday on Lundy Island, where we stayed in the old lighthouse, converted by the Landmark Trust into fabulous holiday accommodation. And so when we were planning our wedding Lundy had seemed the obvious location, if only we could pull it off.

We made it work, but at quite a cost. From a financial perspective, it was only possible if we married out of season. We persuaded the local rector at Appledore, on the North Devon coast, to officiate at the marriage ceremony, and a team of bell ringers to bring the St Helen’s Church to life on the morning of the service. We chartered the MS Oldenburg to bring our guests across from Ilfracombe on the last weekend of February in 1998. And from there it all went wrong. There was a force 9 gale that day, and a crossing that should take two hours took nearly four. Our 60 guests made use of more than 100 sick bags between them, and on reaching land several of them kissed the ground. It was a tough start to our wedding weekend, but the vast majority of the guests took it well. Certainly, the conversation in the pub on the first night was not about how they each knew the bride or groom, but how sick they had been on the boat. I got to spend my honeymoon in the old lighthouse, and it is still a wedding that friends talk about with great fondness, more than 25 years later.

So, 45 years after my first encounter with the flashing light in the attic bedroom, my love for lighthouses endures. I have my own family now, and British holidays invariably involve the coast – and making a beeline to the nearest lighthouse, much to my children’s irritation. But my cycle touring dream remained unfulfilled. As with so many romantic notions, stuff got in the way. You get a job, you buy a house, you get married and have a family. Before you know it, taking twelve weeks off work to cycle around the coast isn’t practical, and just seems a bit indulgent. And in my case, it wasn’t only work and family stuff that got in the way.

Into the dark

Fast forward to March 2008. I am lying flat out on the kitchen floor, dizzy with fear, coming round from having fainted. We have just returned from a week-long family holiday in Belgium. At the start of the week I was absolutely fine, but as the week progressed I felt increasingly exhausted, experienced constant nerve pains in my legs, and every step I took was an ordeal.

The first thing I did when I’d recovered sufficiently was to phone my aunt, the one with the cottage on the Gower Peninsula, who was then a doctor in general practice. Now, I have always adored my aunt Shirley, but if ever there was a time for her to drop her trademark ‘tell it like it is’ approach, this was it.

I described my symptoms over the phone, and she started a response that began, ‘Well, I don’t think it’s multiple sclerosis because if it was, then you’d also have …’ And then she listed a series of symptoms and sensations that I knew I had been ignoring for much of my adult life. And that’s when I fainted.

Over the four years that followed, I was put through an endless array of medical tests and interventions, all of which were inconclusive. Multiple Sclerosis (MS) is an imprecise condition to diagnose formally, and one that the NHS is loath to get wrong. MRI scans, eye co-ordination and balance tests became routine. The results showed that my myelin sheath (the coating that protects the spinal column) was eroding, but not at a rate that required invasive or immediate intervention.

What was frustrating for me, and is for most other MS patients, is that until the myelin deterioration reaches a certain level, no formal diagnosis of MS can be made. I knew very well that I had MS. The consultant neurologist discussed with me how best to cope with the condition, but felt able only to make ambiguous statements such as: ‘You are presenting with symptoms that are consistent with a diagnosis of MS, but could be an unrelated neurological condition or disorder.’

Despite the lack of conclusions from the various tests, my health gradually deteriorated. I had worked for myself for more than a decade, and maintaining any sort of schedule or routine was becoming increasingly challenging. I started to feel a constant fatigue, which meant that I couldn’t get through a day without having a rest, or sleep, for a couple of hours. My legs felt like lead, and buzzed with what felt like an electric current, coupled with near-permanent pins and needles. And then things really took a turn for the worse.

I remember waiting on the platform at Appledore, my local unstaffed railway station, having arranged to meet a friend for a drink further down the line in Hastings. I waited on the platform, conscious that the train was running late. I tried to read the scrolling information sign, but for some reason I couldn’t make sense of the words on the screen, even when I got up close. Instinctively, I covered my right eye, thinking that I might see better with just the left. Instead of helping, everything went dark. I realised that I couldn’t read the display because only one eye was functioning, and the resulting imbalance was disorienting and very frightening. This partial blindness lasted nearly three months, and my sight was only restored with steroids.

The partial blindness prompted a new round of tests and scans, and this time the diagnosis was clear. I had relapsing and remittingmultiple sclerosis, and it was time to talk about ‘disease-modifying treatments’. It might seem strange, but the diagnosis came as a relief. Finally, I knew for certain that I had been right about my condition all the time. There would be no more limbo, no more indecision, no more ‘come back in six months’.

For someone who only has to look at a needle and faint, a treatment involving daily self-administered injections was never going to be easy. Yet of all the treatments offered, it was the option that promised the fewest side effects. Currently there is no cure for MS, and so the principle behind many of the treatments available is to stop or slow down what are referred to as ‘MS episodes’, giving patients more time while waiting for a permanent solution to be developed.

After my diagnosis, people who knew me well thought I was taking everything in my stride. I knew that I didn’t want to be defined by my illness and I was determined never to be the person who says, ‘I can’t do that because I’ve got MS.’ But beneath the façade I was in a permanent state of anxiety. I had stopped dreaming of the future, of what I would and could do – and particularly of my lighthouse-to-lighthouse cycle trip.

With the tiredness, the loss of my sight and the heaviness in my legs, I had resigned myself to the fact that my dream was over. Friends and family rallied round and offered their support, as well as suggestions they imagined might help. Perhaps I could make the trip shorter, by including only the coastal lighthouses and not the offshore ones? Or how about driving rather than cycling? Or visiting a handful of lighthouses each summer, until I had completed them all? All sensible suggestions, but they held no appeal.

It wasn’t just visiting every lighthouse that was important to me. It was the idea of a journey that had no formal end point or time limit. I craved the independence of doing it all under my own steam. I decided I’d rather leave the cycle tour behind than compromise in any way. In fact, I gave up on lighthouses altogether.

It was a bleak time, but salvation was to come.

Just a glimmer

It was Jason, a former client who had become a friend, who managed to rekindle my belief that the trip was still possible. Around ten years earlier, he had realised his own dream by visiting every UK pleasure pier using only public buses. He had always fancied a new challenge and on the surface seemed determined not only to help me, but to join me on the way as well.

Just talking about it with him over a pint one evening brought back some of the old excitement. However well-intentioned, he is also a savvy businessman as well as a great fixer of problems. It didn’t take him very long to come up with a solution for how the trip could still go ahead in spite of my health.

He suggested that my condition meant a bike would be out of the question, and that an Aston Martin DB9 on loan from his local dealer would provide more appropriate transport. He was confident that he could pull it off.

It wouldn’t be possible to visit every lighthouse, he continued, so we should handpick 30 or 40 of the lights most accessible from the principal motorway network. We wouldn’t need much luggage. And there would be no need to wash clothes en route because his PA would simply courier us a bag of clean ones every few days.

Over the course of an hour, what began as a free-range bicycle tour around our coast had become a two-week, high-speed rally sponsored by Aston Martin.

The evening had a profound effect. My passion for lighthouses had returned, the excitement about the trip was palpable, but I knew that compromise on its length or scope was out of the question. So was the Aston Martin. For a while I wondered if this was the effect that he had intended all along. I’m too proud to ask him and, in any case, we are no longer in touch.

Nevertheless, my desire to fulfil the mission had returned. After my initial diagnosis, I had joined several of the MS charities, but it was Shift.ms, a social network for people connected by the condition, where I felt I really belonged. Its founder, George Pepper, was diagnosed with MS when he was just 22, and his response was extraordinary. Deciding to travel the world while he still could, he set off on a six-month adventure to visit India, Japan, Indonesia, Argentina, Brazil and Australia. On his return, he set up the charity to motivate, encourage and bring together other people with MS.

George’s inspiring story resonated with me, and provided confirmation that I had given up on my dream too soon. But it was the Shift.ms motto that really attracted my attention:

MS doesn’t mean giving up on your ambitions. It just means rethinking how to achieve them.

Since starting my daily disease-modifying injections, my health had apparently stabilised. However, there were still two significant hurdles to overcome if I was to re-engage with my dream of visiting every lighthouse around our coast. The first was money. The trip would take more than 100 days, and even if I camped or stayed in budget B&Bs, the cost would escalate out of control very quickly. George Pepper offered to email the Shift.ms membership database, and the desire to support me was overwhelming. The offers of accommodation started to land.

I joined a fabulous charity called the Association of Lighthouse Keepers (ALK), whose remit is to keep lighthouse heritage alive. Their support was also humbling, and by publicising my adventure to their membership, several more offers of overnight stays resulted.

The other hurdle related to my health. My injection routine was helping me feel well, but was it artificial? Could I seriously ride a bike every day, for more than 100 days, covering upwards of 3,500 miles?

I concluded that it was worth trying, recognising that I could switch from a regular touring bike to an electric bike if my health deteriorated. And if I did need or want to swap my mode of transport, it would give my friend Allan his perfect role.

Allan knew only too well of my lighthouse obsession. He was one of the 60 wedding guests who had survived the force 9 gale in the Bristol Channel back in March 1998. He had stayed in the old lighthouse the night before the ceremony, and I think just a little of the magic had rubbed off on him. He had always wanted to play a part in my adventure, and quickly volunteered to keep an electric bike safely in his garage in Oxford and drive out with it to meet me on the coast if the need arose.

The only bike I actually owned was rusting away in the shed, with buckled wheels and a couple of flat tyres. It wouldn’t get me to the first lighthouse on the list, Dungeness, let alone all of them. It’s a shame, really, because it was a very fine bike in its day, an electric-blue Dawes Street Sharp that I bought in 1990, when I lived in London and commuted from Whitechapel to Shepherd’s Bush each day. It must have been one of the last hand-built, British-made Dawes models, before the brand was sold and the factory closed.

My plan, then, was to look for a new touring bike, preferably a British one, that could accommodate my ample frame. At six-foot-five and weighing a shade (ahem) more than sixteen stone, it was unlikely that I could buy something off the peg. My research suggested that just as microbreweries have offered an antidote to the giant multi-brand beer brewers, so dozens of smaller, specialist and highly regarded cycle builders have begun to crop up all over the British Isles. While this meant that I had plenty of choice, I am no cycling expert and had no idea at all about which way to turn.

Allan introduced me to Simon Hood, a keen cyclist and York City FC supporter who had cycled to every game, home and away, over the course of the 2010/11 season. I had read Simon’s book about this mad and ultimately futile venture, Bicycle Kicks, and had enjoyed it immensely.

It was Simon who initially suggested that Thorn Cycles would be a good match for me. I drove down to Bridgewater to meet the company’s founder, Robin Thorn, and their longstanding touring-bike designer, Andy Blance. I had been a little apprehensive about my visit, not least because a Google search had revealed slightly disingenuous descriptions of the two men, such as ‘maverick’, ‘cantankerous’ and ‘abrasive’. I feared that my lack of cycling knowledge and jargon would leave me open to ridicule, but I needn’t have worried.

Andy met me in Thorn’s foyer and gave me a tour of the factory and warehouse. Spread across several outbuildings behind a side street in Bridgwater, it gladdened me that British companies like this still exist. Thorn is the cycling equivalent of Morgan cars. Every bike is hand built from the ground up, and matched and fitted precisely to its rider. With an options list running to dozens of pages, no two Thorn bikes are the same. And like a Morgan, you have to be prepared to wait for it.

Andy talked me through the three principal frame designs from which all Thorn bikes are built, and the advantages and disadvantages of each for an expedition like mine. In all honesty I would have been happy with any of the three, but I opted for the one he described as ‘bulletproof like a Land Rover’. It was a ‘Tonka’ yellow Nomad tourer, with front and back racks and a dynamo hub that powered the lights. The only drawback was that it came with an eight-week wait.

It was now the end of March, and the only major decision left was when, exactly, to set off. I wanted to cover as much ground as I could during school term time, partly because I thought accommodation might be a bit cheaper, but also so that I could perform my parental duties and be with the family during the holidays. I settled for the first Monday in May.

While waiting for Thorn to build my transport, I turned my attention to money. I spent a few days in the garden shed, listing redundant garden machinery on eBay. Simon managed to secure me a complete set of Carradice panniers, a Brooks saddle and a decent Lazer helmet in a series of sponsorship deals. Money would be tight, but it was starting to look as though I would be okay.

I collected the bike from Thorn on the Wednesday before setting off. That left me four days to train and practise, which turned into just two after the delivery of my saddle was delayed until the Friday. I decided to ignore a note that accompanied it, suggesting that it would take up to 100 hours of riding before the seat leather would feel supple and comfortable.

My friend Sue introduced me to her publicity agent, who had managed to secure a handful of press and media interviews. Everyone I spoke to wanted to know about my preparation and training routine over recent months. I lied for the first few, and described tough timed trials along the seafront, filling my panniers with increasingly heavy weights from the gym. But when a charming freelance writer for the Sunday Telegraph asked me the same question, I admitted that I had done absolutely nothing.

Despite the lack of preparation, I was committed. I cycled the five miles from my home to Dungeness and back three times over the May Bank Holiday weekend. It seemed to go okay. I fashioned a bag lined with ice packs to keep my Copaxone injections (my MS medication) as cool as possible during each day’s ride. I practised taking the panniers off and putting them back on again, something that would become a daily ritual.

These were just distractions, however, designed to make me feel prepared, and to muffle the doubt that was increasing by the hour. In May 2015, 45 years after that small boy lay awake in the attic bedroom dreaming of a great adventure, it was time to seek out the lights. All of them.

Day 1

The plan was to set off at 10am and cycle the five miles from home to the lighthouse and cafe at Dungeness, where my family and a few friends would raise a toast and send me on my way. Inevitably, I was still at my desk, tying off loose ends. I was working as a copywriter, and when Allan asked whether I was excited, the only emotion I felt was anxiety about the work that was still to be done and the email inbox that needed to be emptied.

It wasn’t until 9:45 that I started to pack. In fact, I had no idea whether what I proposed to pack would even fit into my panniers. I remembered watching a YouTube video that illustrated how to pack panniers evenly, and which items to pack where. So I did a quick search and watched it again.

Allan and I worked in tandem. I filled a rear pannier with clothes and shoes, then passed it to Allan for weighing. Then I filled the other rear pannier with technology – my camera, camcorder, tablet, Kindle – together with a handful of books, notepads and pens. Allan duly weighed it, only to highlight the massive imbalance. With a fair amount of swapping around, we got the weight roughly balanced between the two. So now it was the turn of the front panniers. In one went my first aid box and a bicycle toolkit. In the other, a month’s worth of pre-filled syringes for treating my MS and the handheld injector gun that delivers the daily dose. Once again, the weight was imbalanced. I halved the contents of the first aid kit. I also took a good look at the cycle tool kit and removed a couple of heavy-looking items whose function I could not determine.

I drank three mugs of coffee, skim read the instructions for my lights, mileage counter, camera and the GPS app on my phone. Like everything else in my life, this was all very last minute. I had the right kit but had not invested the time to get to know how it worked or what it could do. When someone came up with the phrase ‘all the gear and no idea’, they were referring to me.

I have never been able to travel light, and looking down at the four heavily laden panniers in front of me, this expedition was clearly to be no exception. Reluctantly, I compromised a little, rejecting a second casual sweater and a third pair of jeans.

When I finally set off, I took the flat, straight road to Dungeness very gently indeed. This was not a race, I kept reminding myself, and I wanted to arrive at the cafe looking calm and full of energy. I had expected half a dozen to be waiting by the Old Lighthouse at Dungeness, but it turned out to be more like 40. I arrived to cheers, bunting, posters wishing me well and a huge homemade cake. My eldest daughter took on the role of chief photographer, while my youngest proudly held up one end of a ‘Good Luck’ banner. My son Tom seemed bemused by all the fuss. Typically, my parents held back, reluctant to be in the spotlight.

I stayed chatting too long, and it was past lunchtime before I finally set off. I got my camera out to take a picture of the first lighthouse of the journey, and as I did so I heard my friend Dinny say: ‘It’s got to be a selfie, surely?’

It hadn’t crossed my mind, but I realised immediately that he was right. A series of selfies, however indulgent, was the perfect way to record my journey. I took the first one in front of the Old Lighthouse, then cycled the few-hundred yards to the current lighthouse to take my second.

The moment I posted the two photographs online, there was no going back. The expedition had begun.

Dungeness is one of the largest expanses of shingle in Europe and is officially classified as a desert by the Met Office. There have been several lighthouses here, the first built nearly 500 years ago. The receding shoreline left the original 1635 light stranded by the sea, and it was eventually replaced with a 1792 tower designed by the architect Samuel Wyatt. The shifting tides left this tower more than 500 metres from the sea, and a new lighthouse (now known as the old one!) was built in 1904.

The current and old lighthouses at Dungeness.

Following the construction of the nuclear power station in the sixties, another new lighthouse was needed. Built in 1961, this is the lighthouse that operates today. It has a tall concrete tower, with lantern and gallery above. It flashes a white light, once every ten seconds, which is visible for 21 miles.

My journey proper began along the main road to Lydd, the most southerly village in Kent, and then joined a dedicated cycle path towards Camber. A few miles outside Lydd I passed a caravan and camping site, directly opposite an army firing range and next to a vast industrial cement works. The fixed caravans and mobile homes were neatly arranged around the base of a huge electricity pylon, which was humming loudly. At the entrance was a somewhat optimistic sign that read: ‘Do you want the quiet life?’

My first stop was the medieval town of Rye, one of the Cinque Ports, just over the county border into East Sussex. There were once several navigation lights in and around Rye, but after storms changed the course of the River Rother and cut the town off from the sea, the town’s importance as a port began to decline and now no traces of these lights remain.

I was making for Rye Harbour, a popular village and nature reserve about two miles beyond the medieval town centre. As I approached the harbour office, I thought it odd that I couldn’t picture the harbour lighthouse, given that I had lived locally for many years. It was only after opening my guidebook that I discovered that the hexagonal tower had been demolished more than 40 years earlier, and replaced with a pair of cheerless, forgettable wood and metal lattice structures.

I wasn’t expecting my lack of preparation to be apparent so soon. If I had known that these lights were just a pair of beacons, I probably wouldn’t have stopped here. Should I even count harbour lights as lighthouses? This and many other questions ran through my mind, barely three hours after setting off.

I photographed the two lights, before retiring to the excellent Bosun’s Bite cafe. A lean, weathered man in his sixties pointed at my bike and told me that I had made the right choice. He had been riding Thorn bikes for thirty years, and he and his wife toured regularly on a Thorn tandem. Looking at my four heavily laden panniers, he asked me where I was heading, so I told him about my adventure.

‘Wow!’ he replied. ‘You look exhausted! How much further have you got to go?’

I stammered a hasty, non-committal reply, and decided it was time to get going towards Hastings.

The steep climb through Fairlight village was torture, and before long I was off the bike and pushing. Progress was painfully slow, and at one point I suffered the indignity of being overtaken by an elderly lady walking her dog. She told me that I was nearly halfway up, which only served to dampen my mood further.

After Fairlight the going got much easier, and I dropped down into Hastings at speed. There are two lights in Hastings, both operated and maintained by the council, guiding the local fishing fleet back to the shingle beach from which they launch. I made my way to the higher light (known as the rear light), positioned on the cliffs above the shore at West Hill. Normally a sleepy, genteel part of town, today the crowds had descended to enjoy the May Day parade. The freshly mown parkland was strewn with thousands of beer cans and bottles, and hundreds of revellers, many drunk, were singing, shouting, arguing and fighting. When I approached two female police officers to ask where I might find the local lighthouse, they seemed genuinely pleased that I was sober and unlikely to cause trouble. They weren’t locals themselves, however, so couldn’t help.

In one corner of the park I saw what I was looking for: a pentagonal, wooden weather-boarded structure, looking more like a beehive than a lighthouse. This is the rear of a pair of range lights which, when aligned, mark the safe passage for shipping. With its elevated position, it emits a fixed red light with a range of four miles. It wasn’t what you’d call a lighthouse, but it seemed a lot closer than what I had found at Rye Harbour. The front range light at the water’s edge, however, was no one’s idea of a lighthouse – just a fixed red light mounted on a short metal pole.

With photographic evidence secured, I set off along the coast towards Eastbourne, where I was due to stay with Adrian, my go-to graphic designer and illustrator from my days in publishing, who swapped London for a quieter life on the Sussex coast nearly a decade ago. Having driven between Hastings and Eastbourne many times, I remembered it as a fast, busy and dangerous stretch of road. But the National Cycle Network (NCN) Route 2 stayed off-road, hugging the seafront, all the way from St Leonards to beyond Pevensey.

After Pevensey Bay the route returned to the main A259, but by now the road was much quieter and there was a dedicated cycle lane along much of its length.

At Sovereign Harbour I stopped to locate a beacon mounted on top of the Martello tower, one of a number of small defensive forts built along this section of coast to protect against possible invasion from France in Napoleonic times. For the third time that day, I stood in front of a structure that bore little resemblance to a lighthouse, and was conscious of the need to establish a meaningful definition of what counted as one, and what should not.

From Sovereign Harbour I could make out the Royal Sovereign Lighthouse, built by Trinity House in 1971 to replace the lightvessel which had marked the shoal since 1875. It is an extraordinary structure, closely resembling an oil rig, with a rectangular platform containing living accommodation perched on top of a concrete pillar, with a short red-and-white banded light tower and helipad above. It may not be the archetypal lighthouse of children’s drawings, but there is something special about Royal Sovereign. It is one of the last lighthouses Trinity House built, and it plays an important role in guiding shipping away from the many shoals and sandbanks so prevalent off this stretch of coast. Until 2022, it displayed a flashing white light, visible for twelve miles, but has since been decommissioned and dismantled.

Royal Sovereign.

By the time I reached Eastbourne’s elegant Victorian seafront and was less than a mile from Adrian’s house, it was getting dark. Despite arriving two hours later than expected, Adrian and his partner Samina were enormously welcoming and great company. Adrian and I reminisced about the characters we had worked with during our publishing days over a wonderful homemade goulash, a couple of pints of bitter brewed in the Lake District and an excellent bottle of Rioja. Unsurprisingly, I slept very well indeed.

Day 2

I was up early to hear that gales were forecast across the country. Adrian is a keen cyclist himself, and he advised me to get up onto Beachy Head via Duke’s Hill, rather than the route along the main road that I had planned. He warned me that it was quite steep, but that it should only take around fifteen minutes if I took it steadily.

‘Oh! And another thing,’ he said. ‘As you turn the final bend it sometimes gets a bit choppy on the top.’

An understatement, if ever there was one. As I made the final turn, the wind was so strong that it blew me into the bushes with my bike wedged firmly on top of me. I saw a large, empty car park about half a mile ahead of me, which I took to be where tourists parked to walk onto the South Downs. But no matter how hard I pushed, I made no progress towards it whatsoever. Twice more the winds pushed me into the side of the road. I tried getting off the road altogether and onto the slightly more sheltered South Downs Way footpath. For a while it seemed like a good call. But as I emerged from the shelter of a group of gorse bushes, I struggled to stay upright, so for an hour or so I just stayed where I was.

With strength renewed, I pushed back from the footpath to the road, and this time made it to the car park, where by now a solitary ice-cream van was its only occupant. I lay my bike flat on the ground, tapped on the van’s window and shouted my order for a large cornet. The man sealed inside the van made my ice cream, but as soon as it was ready, we both realised we had a problem. The moment he passed my cornet through his window, the ice cream would surely blow away. On the other hand, I wasn’t prepared to hand over my money until the ice cream was safely delivered. There was only one solution, and it was not a dignified one. He opened his sliding window just wide enough for me to poke my head through into his van. For as long as my head remained inside his van, I could eat the ice cream safely. It was only a small van, and I dislike invading people’s space at the best of times. But this really was the only solution. I ate quickly, paid up, locked my bike to a bench, and strode off towards the cliff edge to search for Beachy Head Lighthouse.

For a lighthouse enthusiast it’s unfortunate that I don’t like heights. The closer I got to what I knew to be a sheer cliff edge, the more frightened I became. And with the wind unrelenting, I was simply unable to get too close from fear. Eventually, I found a single spot where I could remain on safe, solid ground and take a very quick photo of the lighthouse hundreds of feet below me.

The current lighthouse at Beachy Head was commissioned in 1899 after the former Belle Tout Lighthouse was abandoned, as it was regularly shrouded in mist and fog. The current tower was brought into service some three years later, in 1902, and is sited at sea level, about 165 metres from the base of the cliffs. It has a tapering granite tower, with lantern and gallery above. It flashes a white light, twice every twenty seconds, which is visible for sixteen miles. The lighthouse was electrified in 1920 and automated in June 1983.

The ride from Beachy Head to the car park below Belle Tout Lighthouse should have been a joyous, five-minute freewheel downhill. Cycling into a fierce headwind, however, it felt at times as though I was actually going backwards. I was grateful there was so little traffic, because the wind would periodically blow me forwards, backwards, out into the middle of the road, or off it altogether.

Belle Tout Lighthouse is currently a luxury B&B, and its location alone makes it a wild and romantic place to stay. Its proximity to the South Downs Way, however, evidently encourages unwanted visitors, and as I circled the perimeter of the tower I noticed signs everywhere discouraging the riff-raff: Private. No entry. Keep out. No access. No parking. Residents only. They gave the place an austere and inhospitable feeling, and although this was a lighthouse I had long wanted to visit, I wasn’t sorry to leave.

Beachy Head.

Belle Tout was built on the cliff top above Beachy Head in 1832, with its location meticulously planned so that the light would be visible for twenty miles out to sea but would be obscured by the edge of the cliff if ships sailed too close to the shore. However, its position so high above the shore was flawed, and the light was frequently obscured by sea mists, significantly reducing its range. More importantly, the chalk cliff face suffered intense coastal erosion, and the light was decommissioned in 1899, replaced by the more familiar Beachy Head Lighthouse at the base of the cliffs in 1902.

The lighthouse has had a varied and chequered history ever since. After the war the building changed hands several times, and was at various times a tea shop, a private dwelling and even a film location, before continuing erosion left it perilously close to the cliff edge. The lighthouse came to public prominence in 1999, when its owners undertook to move the entire structure seventeen metres back from the cliff edge. This extraordinary feat of engineering was filmed and turned into a television documentary.

After refuelling at the National Trust cafe at Birling Gap, I pushed on to Seaford. I had wanted to dislike the place, because I once rented a flat in London from an appalling woman who lived there. She had insisted on leaving most of her belongings in the flat’s cupboards and drawers, spent every day for a month painting a single window frame, disappeared whenever there was a problem, yet always appeared punctually to collect her rent.

As it was, I rather liked Seaford. It felt calm and unfussy. Along the esplanade I passed a row of well-maintained beach huts and a Martello tower. Between them, a tiny seafront cafe serving the richest and most welcome homemade tomato and basil soup. I was their only customer, and I devoured three bowlfuls.

I reached Newhaven at 4pm, much later than I had planned, and headed straight for the harbour. Newhaven lies at the mouth of the River Ouse in East Sussex, and unlike the Kent ports further east at Folkestone and Ramsgate, Newhaven is still an important harbour providing cross-channel connections to the continent for both passengers and freight.

The harbour comprises of east and west piers, with a light on each. On the west pier, the original light was built in 1883, but was rebuilt in 1976 after both the pier and lighthouse suffered storm damage. The east pier originally had a wooden lattice tower with wooden lantern room, but this was rebuilt in steel in 1928, and eventually demolished following vandalism in 2006. Now a 41-foot circular steel pole, painted white with three horizontal green bands, stands in its place.

I could not reach either light up close. The walkway along the west pier was closed off, while the modern east pier light is now controlled by the harbour authority and is inaccessible to the public. I cycled to a large car park close to the west pier to get the best view of both lights.

Leaving Newhaven shortly before six, the route to Brighton was a straight dash along the coast, passing through Peacehaven and Saltdean, before descending down onto Brighton Marina. At the end of the west arm of the breakwater, there is a modern light mounted on a cylindrical concrete tower, displaying a quick-flashing red light. It is not a landmark of great beauty, but it was no less a lighthouse than several I had seen so far, so I was glad to mark it as ‘bagged’.

I was due to stay with Jacqueline and Andy, who offered to put me up after responding to a request for help from Shift.ms. They lived on an elegant street a mile from the seafront, together with their three children, Dylan, Lauren and Natasha, who turned out to be, unquestionably, the most polite and well-mannered kids I have ever met.

I arrived at around seven, and by half past, at their recommendation, I was sitting in the nearby Preston Park Tavern with my food ordered and a pint of Hop Pocket in my hand.

Days 3 and 4

As I made my way back to the seafront the next morning, I was struck by how well Brighton caters for its cyclists. Almost every road in the city centre has a dedicated cycle lane, many with their own set of lights and right of way. The promenade, too, separates pedestrians and cyclists effortlessly, and although it was busy, I was cycling out of the city towards Shoreham in no time.

Shoreham Port is one of the largest cargo-handling ports on the South Coast, and there are a number of navigation lights in evidence. However, I was here to see the grey limestone tower on the seafront, with its cast-iron and copper lantern. It was built in 1846 and began life as a fixed oil-burning light, but was converted to gas in the 1880s, with a rotating light using a mechanism similar to a long-case clock. The lighthouse remained gas powered until 1952, when a new fixed electric light was installed. It currently has a range of ten miles.

The NCN Route 2 follows the seafront from Shoreham to beyond Worthing, but as the winds had now become gale force, it became impossible to continue on it. I found myself employing the principles of barely remembered weekend sailing lessons, tacking my route away from the seafront with a series of right turns, and then turning back again towards the sea a few-hundred yards later with a series of left turns. Progress was painfully slow, with just the occasional sympathetic nod from a solitary dog walker to encourage me. At one point I was overtaken comfortably by a stray wheelie bin, which had broken free from its owner’s driveway.

In the five miles to Worthing I learned one valuable lesson. Each time I tried riding my bike in these winds, I elicited pained looks of sympathy from the few people I passed, as if they felt they should offer to give me a push. But if I got off the bike, I gave the impression that I had all but completed my journey and was just pushing my bike the final few-hundred yards to my destination.

So I continued, cycling when I was able to keep away from the seafront, and pushing when it seemed the better option. Despite the slow pace I reached Littlehampton at around 4pm and made straight for the harbour.

Littlehampton once had a pair of small wooden weatherboarded leading harbour lights that were affectionately referred to as the salt and pepper pots. They were built at either end of the east pier, with the high light completed in 1848 and a shorter low light completed in 1868.

Concerned that an invasion force might use the lights as navigation aids, they were demolished in 1940. After the war ended, a pair of lights was built in the same location in 1948. The current rear range light is a futuristic-looking, white-painted, concrete tower whose light is visible for ten miles. The current front range is a simple fixed green light mounted on a black column.

I rather liked Littlehampton and was delighted when the Facebook post announcing my arrival had attracted the attention of Philip, an old friend from London. I first met him 30 years ago, when I rented a corner of his girlfriend’s living-room floor each weekday night to avoid having to find a place of my own. After a comfortable night only yards from the harbour, we met for breakfast, and while I contemplated my greying beard and expanding waistline, I was irritated to see that he looked exactly the same as he did back then. He may have moved out of London, got married, had children then divorced, yet he seemed as relaxed and untroubled by the world as he did all those years ago.

Leaving Littlehampton behind, the seas and wind were calmer, and I was happy just to let my GPS guide me to the next lighthouse at Southsea, some 40 miles further along the coast. Initially, the route took me inland to Yapton, and then meandered back to the coast at Bognor Regis, before heading inland once more into Chichester.

Chichester is a wonderfully preserved Georgian cathedral city with wide, prosperous streets surrounded by ancient city walls. I was last here to visit my friend Kate, a nutrition expert, who had moved out of London a few years earlier to an extraordinarily old, beautiful, beamed and low-ceilinged town house. My route took me straight past her front door.

Over lunch in the city centre, I noticed that NCN Route 2 followed another long section of the dreadful A259 road that had caused me such grief with Bank Holiday traffic on the first day. I was confident I could do better, and set off along a series of small lanes, cycle paths and tracks through Bosham and Chidham, before finding myself on a wide, apparently abandoned stretch of traffic-free road. I cycled its length joyously, revelling in my ability to use my nose to find the best route. But after following the road for a couple of miles, it stopped abruptly at the entrance of the Baker Barracks, guarded in number by armed soldiers of the Royal Artillery.

I retraced my steps and followed the route I should have taken from the start. After Havant, I managed to stay away from the main road, with large expanses of water to my left and unspoiled views across to Hayling Island.

I approached Southsea Castle along the splendid Eastney Esplanade, from where I got my first view of the Solent and the Isle of Wight. The castle was built in 1544 and was part of a series of coastal fortifications constructed by Henry VIII. It was extended and largely rebuilt in the early 1800s and the lighthouse, commissioned by the Admiralty, was constructed on the western gun platform in 1828, rising 34 feet and built into the castle’s outer walls. The stone tower is painted white with black bands, and its flashing white light can be seen for eleven miles.

Day 5

I was up and off the next morning, excited at the prospect of organising a boat trip out to the Palmerston Forts. These four remaining granite and iron forts were built in the Solent between 1867 and 1880, after Prime Minister Lord Henry Palmerston commissioned them to defend the Royal Navy fleet in Portsmouth harbour against a Napoleonic invasion. The French invasion never materialised, and they came to be referred to as ‘Palmerston’s Follies’.

All four forts originally housed lighthouse towers on their roofs, and two have since been converted into luxury hotels. The concierge was based down at Gunwharf Quays, so I headed there full of enthusiasm. My excitement was short-lived, however, after one of the Solent Forts hotel group crew informed me that the only way I could visit would be to book a Sunday lunch package at £160 per person. Alternatively, I could opt for a two-night, two-dinner ‘trio of forts experience’, but she declined to mention the price for this, having seen my face drop at the cost of lunch.

I settled for a long-lens photo of Spitbank Fort from Southsea, and later saw Horse Sand Fort and No Man’s Land Fort from the Isle of Wight ferry, and finally St Helens Fort from Nodes Point on the Isle of Wight.