18,72 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Quiller

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

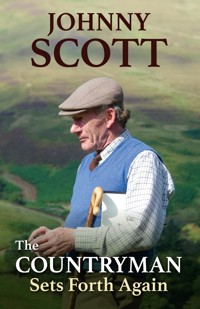

The Countryman Sets Forth Again is a wonderful compilation of articles covering a range of eclectic rural and countryside subjects. There is something for everyone to discover from the ancient language of field sports to the treasures to be found in old barns; the history of the landscape to dryland husky racing and much more.Divided into seasonal sections and featuring more than forty-five chapters, many of the articles have appeared in The Field magazine. Here are all aspects of country life described in vivid detail, from the flora and fauna to the folklore. Descriptions of ancient customs feature alongside accounts of pigeon racing and hound trailing; and stories of exotic plant hunters from past centuries. Readers will encounter mad March hares, owls, ravens, bats, pike, eels, and the rare capercaillie. Other subjects include coppicing, ancient trees, hanging game, stoats, terriers and, that perennial British favourite, the weather. The author also takes us back to his childhood with memories of charcoal burners and of harvesting wild food.Combining his engaging writing, expert insight and immense knowledge, Johnny Scott is a master at celebrating and chronicling the countryside. In this book he continues to convey his wisdom and affection for the magic of nature and rural life.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 353

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Ähnliche

Clarissa and the Countryman

Clarissa and the Countryman Sally Forth

A Sunday Roast

The Game Cookbook

A Greener Life

A Book of Britain

The Countryman Through the Seasons

We are indebted to The Field for its kind permission to reproduce material originally appearing within its pages.

First published 2023

QuillerAn imprint of Amberley Publishing Ltd

Copyright © Johnny Scott, 2023

The right of Johnny Scott to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN 9781846893827 (HARDBACK) ISBN 9781846893834 (eBOOK)

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Typesetting by SJmagic DESIGN SERVICES, India. Printed in the UK.

Quiller

An imprint of Amberley Publishing Ltd

The Hill, Merrywalks, Stroud, GL5 4EP

Tel: 01453 847 800

E-mail: [email protected]

Website: www.quillerpublishing.com

Contents

Introduction

Spring

Landscape

Adders

Laughing Frogs

Mad March Hares

Wise Owl

Folklore and Customs

The Jethart Ba’

Fighting Shrews

Charcoal Burners

Pigeon Racing

Lockdown

Bracken

Summer

Soft or Hard Grouse?

Slippery Eels

Golden Gorse

Bats

Hound Trailing

Ravens

Reading the Weather

Strewing Herbs

Ancient Trees

Kit

Exotica

Terriers

Autumn

Hanging Game

A Mast Year

Dryland Huskies

Elder

Autumn Bounty

Wild Fungi

Capercaillie

Winter

Ferrets

Otter

Pike

Snipe

Britain’s Alpine Heritage

History in a Wall Head

Starlings

Stoats

The Golden Queen of the Woods

Coppicing

Our Fathers of Old

Grey Geese

The Language of Field Sports

Campanology

Sighthounds

Yule Log

January

Introduction

The Countryman Sets Forth Again is the sequel to my previous book published by Quiller, The Countryman Through the Seasons and, like its predecessor, is a compilation of articles I have written over the years for TheField magazine and other publications, containing a mixture of topics including field sports, wildlife, natural history, customs, traditions, and folklore of rural Britain. As before, it is perhaps more in the nature of a scrapbook in which I have recorded vignettes of the odd incidents and episodes which nature has provided to excite my interest, as the wheel of the seasons turns. The sound of a vixen screaming to her mate on a frosty, moonlit winter night; the territorial drumming of cock snipe on a moorland fringe in springtime and the glory of wild flowers in early summer. Badger cubs playing at the mouth of a sett; a hen grouse scuttling through the heather dragging her wing to draw one away from her nest, or the strange outlines on the land that become visible after a fall of snow, indicating some ancient human occupation.

So much of the British countryside has been lost to us during my lifetime, not just through roads, railways, intensive farming and ever-expanding urban sprawl, but because people have lost their connection to the natural world. When I was a child, all children of my age had one thing in common, regardless of background; nature was our principal source of daily entertainment. Urban children learnt about natural history in city parks, railway embankments, churchyards and canal banks, whilst rural ones had the freedom of the countryside. To be outside, whatever the weather, was considered an essential, healthy, beneficial and profitable way for the young to spend their time. These were the philosophies around which the Scout movement, that did such exemplary work in introducing inner-city children to country lore, had been based.

As children we learnt the seasons of birds, animals, reptiles and insects; the ones that hibernated and those that were nocturnal; the predators, the quarry they hunted and the corridors of safety, such as hedgerows, that smaller animals used as habitat, or links to woodland sanctuary. We were taught which plants were edible and those that were poisonous; how to read the weather from the way wildlife responded to differing atmospheric conditions and we knew how to recognise the presence of animals by identifying their tracks. We absorbed our knowledge on a daily basis from our elders – there were many more people working on the land in those days, but the nation as a whole knew more about the natural history of these islands than at any other time before or since, simply through necessity. Rationing lasted from 1940 to 1954 – a staggering fourteen years during which everyone had to forage for nature’s seasonal bounty to bolster their diet.

The post-war arcadia of my childhood underwent dramatic changes during the sixties and seventies as government policies of agricultural intensification created a chain reaction of loss across the spectrum of wildlife. Vast quantities of habitat were destroyed in parts of Britain as hedgerows were bulldozed out to create bigger fields, old pasture, heath and downland ploughed and marshes drained under devastating Ministry of Agriculture reclamation schemes aimed at making Britain self-supporting. Herbicides and pesticides destroyed the habitat and food source of many small birds, reptiles and mammals, which in turn impacted on the larger species that depended on them. At the same time, the Forestry Commission embarked on a massive programme of planting quick-growing Sitka spruce conifers. Huge areas of land were planted, much of it in areas of outstanding natural beauty and totally unsuited to growing trees, the Highlands of Scotland, for example, or the uplands of Wales and northern England – Kielder Forest alone sprawls over 160 square miles of the Northumbrian hills. Rural communities disappeared; acres of ancient natural woodland were engulfed and in a matter of twenty years, these plantings had become vast black blocks of sterile woodland.

As machinery increasingly replaced manpower, 50 per cent of the agricultural workforce left the land to seek alternative employment in towns. The self-supporting infrastructure of villages became eroded, many of the old rural crafts died out and much country lore, handed down from generation to generation, was lost. As agricultural reclamations destroyed the hedgerows and small broadleaved woodland, they took with them the urban tradition of coming out into the countryside every autumn to pick nuts and berries.

Technology has now enabled more and more people with urban-based employment to live in rural areas and to reap the benefits for themselves and their families from living in the countryside and yet, so many of them feel ill at ease in the midst of their natural heritage through lack of knowledge. A combination of bureaucracy, ill-advised agricultural policies, ignorance and prejudice have combined to obliterate so much of the precious culture of our Sceptred Isle. Gradually, the much vaunted urban–rural divide became established, fuelled by field sports becoming a political football as socialist politicians encouraged lobbying by commercially motivated single issue animal rights activists, forcing genuine country people into becoming an ethnic minority.

It is all still there though. The romance, antiquity and beauty, but our rural culture, heritage and traditions; the catalyst that binds many communities together and provides them with the folklore that defines their regional identity has become very fragile and sadly, there are those motivated by personal gain, who seek to destroy it for ever.

The wonder of the world; The beauty and the power,

The shapes of things; Their colours, lights and shades,

These I saw; Look ye also whilst life lasts.

Spring

Landscape

The British landscape is an extraordinary creation; immensely ancient and full of enchanting surprises which open little windows of our history. I cannot believe that any other country has such a diversity of interest packed into a smaller space. It is impossible to go from one parish to another without coming across some arresting reminder of the country’s past, each with a story to tell – an Iron Age fort, a strangely corrugated field, a ruin, a folly, a venerable tree, a stone circle, castle, sunken lane, ancient bridlepath, right of way, old stone farm building or simply an isolated patch of nettles, indicating that humans had once settled in the immediate area. Every day on my farm here in a remote part of the Scottish Borders, I walk past the physical memorials to previous occupiers of this land going back dozens of centuries. On a bank above the Whitrope Water is a boggy area of ground called Buckstone Moss, named after the Buck Stone, a Neolithic megalith erected perhaps 3,500 years ago by dreamy prehistoric pastoralists. There are the visible remains of the earth banks that surrounded the little fields attached to the Iron Age fort on a hill called the Lady’s Knowe. Below these lie the Lady’s Well, a freshwater spring revered by the Celts long before the nearby chapel, part of the Hermitage Castle, was dedicated to St Mary.

Between the Lady’s Well and the ruins of St Mary’s Chapel are a jumble of mounds and earth banks assumed to be the remains of the motte-and-bailey castle built by Sir Nicholas de Soules, Lord of Liddesdale, in 1240. Further on, beside the Hermitage Water, on a bank above a deep pool is an oblong hump, reputedly the grave of Sir Richard Knout, Sheriff of Northumberland, who was killed by retainers of the de Soules family in 1290 when they rolled him, in his armour, ‘into the frothy linn’. Then there is the grim awesome ruin of the Hermitage Castle, ‘the guardhouse of the bloodiest valley in Britain’, where, in 1566, Mary, Queen of Scots had the infamous meeting with her lover, James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell.Back in the body of the farm, a great wall of boulders, known as the White Dyke, runs across the middle of Hermitage Hill, said to be part of the deer ‘haye’ or funnel into which deer from the castle deer park were driven and slaughtered.

There are more stone walls or dykes built in the eighteenth century during the Acts of Enclosure, when gangs of Irish labourers built mile upon mile of walling across Scotland and Northern England. At much the same time, drainers dug open drains all over the hill to improve the quality of the grazing and built ‘cundies’ (conduits) to carry water from one of the hill burns to power the water mill at the steading. An old drove road runs down the side of the farm’s northern boundary through an area known as the Mount; at the bottom are the ruins of an old toll house and the earth banks of Mount Park, where cattle from all over south-west Scotland rested for the night on their long journeys to the trysts in the north of England. The ‘old’ steading, a handsome range of slate-roofed stone buildings – cattle byres, cart sheds, granary and stabling – was built in 1835; the ‘new’ steading, a hideous open-span erection of steel girders, asbestos and concrete, was put up in the 1970s, when the government was offering subsidies for new farm buildings during a drive to increase agricultural output. I mention all this in detail because my farm only covers 600 hectares and although having a castle on the doorstep adds a certain amount of added historical interest, the visible traces of preceding generations are similar to those of all other farms in the country.

Virtually every corner of the British Isles, from the tip of Cornwall to remotest Hebridean Island, has been owned and tilled, cropped and grazed for at least 7,000 years. For all its wonderful areas of remote, rugged and natural beauty – the Cumbrian Fells, the Cheviot Hills, the savage grandeur of the Highlands or the moorland of the West Country – Britain is the least wild of any country on the planet. It has been estimated there is not a yard of land that has not been utilised by someone since the arrival of Neolithic man, and the landscape we love and admire is entirely man-made. The rolling heather-clad hills of Scotland are most certainly man-made – even the Broads, the stunning network of lakes and rivers covering 300 sq km of Norfolk and Suffolk. Until the 1960s, when the botanist and stratigrapher Dr Joyce Lambert proved otherwise, this vast wetland area was believed to be a natural formation. In fact, they are the flooded excavations created by centuries of peat extraction. The Romans first exploited the rich peat beds of this flat, treeless region for fuel, and in the Middle Ages the local monasteries began to excavate the peat as a lucrative business, selling fuel to Norwich, Great Yarmouth and the surrounding area. Norwich Cathedral, one of the most stunning ecclesiastical buildings in Britain, was built with money from 320,000 tonnes of peat dug out of the Benedictine lands every year, until the sea levels began to rise and the pits flooded.

During this incredible longevity of occupancy we have developed a passion for our countryside, a bond and an affinity with the land that is uniquely British. This love affair has been expressed throughout history by an almost obsessive desire to draw attention to the landscape by affectionately adding what was considered at the time to be an improvement to nature’s already superlative offering. Britain is covered in decorated summits, follies, woodland plantings, individual trees, artificial lakes and monuments, all carefully sited to improve the vista and all constructed as a statement of gratitude.

Our Bronze Age and Iron Age ancestors were among the most diligent of landscape enhancers, compulsively building henges, erecting megaliths and carving hill figures where the colour of the chalk or limestone substrata would show up in contrast with the green of the surrounding sward. Undoubtedly the most famous of these is the White Horse of Uffington, high on an escarpment of the Berkshire Downs below Whitehorse Hill, a mile and a half south of the village of Uffington, looking out over the Vale of the White Horse.

For a piece of artwork which optically stimulated luminescence dating has proved to be 3,000 years old, the highly stylised curving design is extraordinarily contemporary. It was either the late Bronze Age or early Iron Age occupants of the adjacent Uffington Castle hill fort who devoted the immense amount of time, organisation and effort required to carve the 110-metre creature into the hillside and, despite endless hypothesis, no one really knows why. From my perspective, you only have to look at it for an explanation: the horse is a thing of beauty, young, sleek and vibrant, lunging forward with neck arched and forefeet raised, a picture of health and vitality. The carving was deliberately constructed just below the summit where it would be visible to other hilltop settlements and the horse triumphantly shouts a message from his tribe across the wooded valleys: ‘Look at me.’ The horse rejoices, ‘Am I not magnificent? See how beautiful and fertile my hill is.’

Unless the substrata was regularly kept exposed, a hill carving would disappear back into the ground within a decade and there will have been hundreds of them dotted around the uplands which are now lost to us. The two Plymouth Hoe Giants, visible until the early seventeenth century, are an example, or the Firle Corn, a nearly lost hill figure on Firle Beacon, in Sussex, now looking more like a small ear of corn or a strange weapon than a human figure, whose existence can only be seen by infrared photography. What is so remarkable about the Uffington Horse is that for over thirty centuries whenever the turf looked like growing over it the local people have always cleared it away. Long after the original architects had passed on and whatever religious, totemic or cultural significance attached to the carving had been forgotten, successive generations have preserved the carving through all vicissitudes, simply because they liked having the horse on their hill and felt it looked better with it, rather than without it.

Some hill figures are of dubious provenance. There are no historical records of the priapismic Cerne Abbas Giant before 1694 and there is considerable evidence to suggest that it was created on the instructions of the landowner, Lord Holles, as a parody of Cromwell. Others have been resurrected by nineteenth- and twentieth-century archaeologists – whose enthusiasm has almost certainly changed the original outlines. The Long Man of Wilmington dominating a broad sweep of the South Downs near Eastbourne is an example. The origins of this 70-metre-high figure have been the subject of endless debate, ranging from a heretical image carved by a secret occult sect of the monks of Wilmington Priory during the Middle Ages; a Celtic sun god opening the dawn portals and letting the ripening light of spring flood through; a Roman standard bearer, or a deeply symbolic prehistoric fertility symbol. Unfortunately, many of the original features were lost in 1874, when the outline was altered to make it appear more impressive, but I have no doubt that the Long Man was made by the late Bronze or early Iron Age tribesmen who occupied a substantial settlement on the summit of Windover Hill immediately above it.

Why did the ancients carve a giant man there? I believe, as with the White Horse, they were broadcasting pride of ownership of that particular hill settlement. One thing is certain, the lovely curvature of the Downs and the uniform, slightly convex slope between the two almost identical spurs on which the Long Man has been carved would pass completely unnoticed if he wasn’t there. All the hill carvings, the few ancient ones which have survived or been resurrected and the many that were created in the nineteenth century during the great era of naturalist landscape design, draw the eye to a pleasing feature of landscape.

The exertion that went into digging out hill carvings pales into insignificance when compared with some of the other creations that display an extraordinary commitment of time and effort for no apparent purpose. Silbury Hill near Avebury, in Wiltshire, is the tallest, prehistoric, human-made mound in Europe and one of the largest in the world – similar in size to some of the smaller Egyptian pyramids of the Giza Necropolis. Composed mainly of chalk and clay excavated from the surrounding area, the mound stands 40 metres high and covers about 2 hectares. It is an exhibition of immense technical skill and prolonged control over labour and resources. Archaeologists calculate that Silbury Hill was built nearly 5,000 years ago and took 18 million man-hours, or 5,000 men working flat out for fifteen years to deposit and shape 250,000 cubic metres of material. This incredible structure contains absolutely nothing; no burial chamber of a great tribal chief and not one iota of treasure. A huge disappointment to the first Duke of Northumberland who employed an army of Cornish miners to burrow their way through the hill in 1766, convinced they would find him some loot. There is no explanation why anyone should want to build Silbury Hill, apart from the indisputable fact that it looks jolly impressive in the middle of an otherwise flat piece of ground.

Equally peculiar are the inexplicable earthworks known variously as black-dykes, devil’s dykes or Grim’s dykes, found from the south of England right up into southern Scotland and as far north as Shetland. These consist of a ditch and mound of varying dimensions which follow a winding course across country, often traceable for miles. The great trench and mound of the Devil’s Dyke in Cambridgeshire and the long line of Offa’s Dyke on the Welsh Marches are two of the most well known. The Devil’s Dyke runs for 12 km from the flat farmland of Reach, past Newmarket to the wooded hills around Woodditton, periodically reaching a height of 11 metres. Offa’s Dyke is the massive 200-km linear earthwork, 20 metres wide and about 3 metres high, which roughly follows part of the current border between England and Wales. There are several other remains of earth banking: Grim’s Ditch in Harrow; the Black Ditches at Cavenham in Suffolk; the Brent, Bran and Fleam Ditches in Cambridge, and Woden’s Dyke in Wiltshire. In southern Scotland we have the Catrail, which meanders 22 km from Roberts Linn, just up from the farm, to Hoscote Burn in south-western Roxburghshire. The 8-km Picts Work Ditch, from Linglie Hill to Mossilee, near Galashiels, and the Celtic Dyke in Nithsdale, Dumfriesshire, runs for about 27 km parallel with the River Nith between New Cumnock and Enterkinfoot.

Scottish ‘black dykes’ are small compared to the others, being about 2.5 metres at the base. Most of these earthworks appear to have been constructed by Bronze Age and Iron Age people, with some in the early Anglo-Saxon period and all, even Offa’s Dyke, share one thing in common: for all the labour and energy that must have gone into building them, they serve no recognisable function. They are demonstrably not defensive; in most cases they are so short that an enemy would simply nip round the sides or, in the case of Offa’s Dyke, it would be impossible to man the entire length effectively. They are obviously not boundaries and a theory popular among nineteenth-century Scottish historians, that they were built to hinder neighbouring tribes escaping with stolen livestock, was quickly discredited. The sort of semi-wild farm animals that were around in those days would easily have been driven through the wide ditch and up the slope of the earthwork.

I find it absolutely delightful that these ancient earthworks have completely stumped the theorists and not even the silliest neo-pagan can claim them as some sort of fertility symbol. So why were they built? In the absence of any other explanation, I presume the motive was similar to that which gave us Silbury Hill; someone must simply have woken up one morning and thought a big earth dyke in this or that location would improve the look of the landscape.

Adders

A little April sunshine and the moorland above the farmhouse throbs with the birdsong of migrants from their coastal winterings who nest every year in the uplands: oystercatchers, curlews, lapwings, snipe, redshanks, greenshanks, golden plover, skylarks, merlins, short-eared owls and the occasional dotterel. A glorious cacophony of mating calls, heralding the start of spring – as is the appearance of the adders I see every year, basking on a bare patch of ground among old heather on a south-facing bank above their hibernation site, the heap of stone from an old sheep stell that collapsed long ago. Vipera berus, Britain’sonly venomous reptile, are short stocky creatures with disproportionately small heads, easily identifiable by the dark zigzag pattern along the length of their back. The male is between 60 and 70 cm long and varying colours of grey and khaki, whilst the larger, stouter female is more brown or red. In both cases the belly is grey and the throat, cream. Adders have the widest distribution of any snake and are found throughout Europe and Scandinavia, across Russia and Asia to northern China and are the only species found inside the Arctic Circle. They occur in a range of habitats from heathland, woodland glades and moors to grassy cliff tops, sand dunes and railway embankments. Their principal requirement seems to be an open, dry, sunny environment free of urban populations, with enough rough cover to escape to when disturbed.

Adders seek hibernation sites when the glass drops in October, with males emerging in early spring several weeks before females, to absorb warmth and vitamin D from sunlight as their sperm develops. They do not feed during this period and continue to live off remaining body fats stored the previous summer. In due course, as the females start appearing they become more active; last year’s dusty skin is shed and the male, gleaming brightly, sets off following a female’s scent trail with his tongue, which acts as the olfactory organ. Once a female has been located, the male writhes over and round her, flicking his tongue along her body and tapping her with his head, becoming almost convulsively frantic in his attentions as she responds and releases pheromones. If another male appears, the first will defend his position aggressively and an ‘adder dance’ ensues taking the form of a wrestling match until one concedes defeat. To assist copulation, adders have been provided with a bifurcated hemipenes covered in spines and once male and female have joined, they may remain locked for up to an hour; if disturbed, the female glides away dragging the male behind her.

Sexual maturity is reached by males at three to four years and females, a season later. Female adders who have bred are generally desperately undernourished as they enter hibernation and only reproduce at most, every other year. Adders give birth to live young and with gestation lasting around twelve weeks, the female needs to feed hard as soon as mating is over to build up fat before advancing pregnancy reduces her ability to hunt. Between five to fifteen brick-red young, 20 cm long are born fully active towards the end of August and into September, receiving no parental attention and leaving their mother within thirty-six hours. Prey consists of small mammals – shrews, voles and field mice, lizards, frogs, toads and during the nesting season, fledglings of ground-nesting birds. Adders hunt using their tongue to follow scent and heat sensors located on their slightly upturned snout which detects the prey’s body warmth. Quarry is killed with a bite from hollow, hinged fangs through which venom is injected from glands in the upper jaw. These fold back and the wide opening upper and lower jaws move independently, allowing adders to swallow victims whole, whilst enzymes in the digestive tract break down all bones and tissue except fur.

Although poisonous, adders are not aggressive and their danger is largely exaggerated. They are more anxious to avoid people than to attack and usually slither into cover when they detect the ground vibration of an approaching human. Bites happen through accident or stupidity and are rarely fatal – the last death was in 1975 – the effect varies from localised discomfort and swelling, to vomiting and diarrhoea, although dogs are particularly at risk in the spring when the haemotoxic venom is more potent. Until well into the twentieth century, ointments made from adder fat were the universal cure-all for bruises, rheumatism, deafness and snake bite, with adder catchers in various parts of the country making a decent living catching and selling adders to quack doctors. Perhaps the most famous snake catcher was Harry Mills, who died in 1905 and is reputed to have caught over 20,000 snakes in the New Forest during his life. Since 1981, adders have been protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act from being killed, injured or sold.

Adders have few predators. A hungry brock will take the odd one; a fox with nothing better to do might torment an adder until it is exhausted and kill it. Hedgehogs occasionally eat them and basking adders run the risk of being spotted by buzzards. Although not threatened with extinction in Britain or considered a priority species under the UK Biodiversity Action Plan, adders are endangered in certain areas through habitat loss to agricultural reclamation, motorways and urban spread. Assessing the adder population is now of considerable importance and the Herpetological Conservation Trust would be enormously grateful for information on adder sightings this spring, so keep your eyes peeled.

Laughing Frogs

The Cooling Marshes, on the Hoo Peninsula, was an area I knew well in the 1970s. Part of the North Kent marshes that run beside the Thames from Shorne to Allhallows at the mouth of the estuary, they are an isolated sanctuary in a heavily urbanised area surrounded by industrialisation. All marshes are atmospheric but these ancient grazings are more so than any others I know. Iron Age settlers, the Belgae, Romans and Saxons all left their mark. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the tidal creeks were the scene of intense smuggling activity, with contraband carried to the sinister Shades House, from Egypt Bay, a sheltered anchorage named after African slavers and their cargoes of ‘Egyptians’. These marshes were the inspiration for Dickens’ Great Expectations, but above all, they have always been a haven for a multitude of wildfowl, a natural bounty harvested for centuries to supply the demand in London, as names like Decoy Farm and Decoy Fleet suggest.

I came back to this eerie part of the world for the first time in twenty-five years the summer before last, to see an area of marsh that had been purchased by the Kent Wildfowling and Conservation Association with support of grant aid from the Nature Conservancy Council. Following the track past the ruins of Cooling Castle, out towards the sea wall to meet Allen Jarrett, the KWCA president and Phil Eliot, who manages this part of their landholding, at the famous Cooling Black Hut, a wildfowlers’ refuge built from driftwood under the sea wall.

Walking across the marshes to look at one of the ‘scrapes’, shallow depressions which when flooded, provide KWCA members with spectacular duck flighting, I could hear above the sound of teeming flocks of waterfowl and waders a curious, incessant quacking from a big ditch behind the mounds of old Roman pottery workings. It was an odd sound, that stopped just short of recognisable. ‘Widgeon?’ I enquired. ‘That’s what I thought, the first time I heard them,’ Phil told me, ‘but it’s not. It’s those Continental frogs. There are thousands of them, all over the marshes.’

Almost immediately I saw one, sunning itself among the sea club rushes on the edge of a dyke. About the size of a common toad, with a pointed snout, light-green head and olive body speckled with black, warty protuberances, the frog gazed at me defiantly through golden eyes before leaping sideways, to land with a plop in the water. This started a chain reaction down the length of the dyke as more basking frogs, sensing a predator, took to the water. With identification, their raucous quacking, which had at first seemed localised, now became an irritating background sound right across the area. A foreign reptilian intrusion on the familiar beauty of marshland music.

Rana ridibunda, the ‘laughing frog’, so called because its duck-like mating call resembles a chuckle, are the largest frog in Europe – Phil has seen them with a body as big as 13 cm long – has a distribution among European river valleys, ranging from Denmark to the southern Balkans and across Spain, Portugal and the south of France. More commonly called marsh frogs, they were unknown in Britain before the mid-1930s and the story of their introduction and subsequent colonisation is, like most invasive species, a pretty quixotic one.

In 1935, the playwright, and author, E. P. Smith, acquired twelve marsh frogs from University College, London, which had been imported for scientific research from Debrecen in Eastern Hungary. These were released into the pond in Smith’s garden at Stone-in-Oxney beside the old Royal Military Canal, overlooking the lovely Walland and Romney marshes. It has been suggested that Smith wanted the frogs to remove mosquito larvae from his pond and that the idea, in those pre-DDT days, was inspired by publicity surrounding the recent introduction of giant marine toads to control grey-backed beetles in the Queensland cane fields.

The frogs, who have a voracious appetite, will eat virtually anything they can get their mouth round, including all invertebrates, small crustaceans and fish, adult newts, other frogs and the occasional mouse or fledgling. They made no impact on the mosquitoes and, preferring deeper water than was on offer in Smith’s pond, very soon decamped. The network of drainage ditches, dykes and waterways that criss-cross the marshes proved an acceptable habitat and the frogs began to breed. Female marsh frogs are very prolific and can lay between 4,000 and 12,000 eggs, depending on body weight. Not surprisingly, within three years they had colonised an area of Romney Marsh extending to 46 sq km. E. P. Smith, who took a very proprietorial interest in the frogs’ progress, as fellow members of the Garrick Club knew to their cost, was apparently delighted. The inhabitants of the marshland villages, considerably less so.

During the breeding season which starts in May, male marsh frogs become extremely vocal, inflating a grey, pea-sized sac on either side of the mouth to emit their loud, exuberant love song. The noise, which can carry for miles and is described succinctly by Phil as ‘deafening’, reaches a crescendo through June and continues sporadically into September, when the weather cools and the frogs start thinking about hibernating. Unlike our common frog which mates in February and March, considerately piping down after dusk, marsh frogs become even more vocal during the night. Such was the noise disturbance that the local MP was soon being lobbied by furious residents, demented through lack of sleep, to raise a question in the House of Commons. Unfortunately, political interest in marsh frogs was overtaken by world events and they continued to spread unimpeded across the marshes throughout the war years.

By 1960, the whole of Romney, Walland, Denge and Winchelsea Marshes, an area of 160 sq km, was thoroughly colonised and E. P. Smith had prudently moved to another part of the country. They were on the Isle of Sheppey by the early seventies and Phil mistook them for widgeon on Stoke Saltings, at the mouth of the Medway, early in the season of 1979. He first saw them out on Cooling Marshes nine years ago. Meanwhile, marsh frogs were becoming established by human agency elsewhere. A farm labourer near the Lewes area brought some frogs back from the Romney Marshes in 1974, which subsequently escaped into the Lewes Brooks and have spread across marshland on either side of the River Ouse, south to Newhaven and north to Barcombe. There is another population in the vicinity of Heathrow, reputedly turned into the wild by a soft-hearted customs official and there have been further releases on the Somerset Levels and further north, on the marshes off the Humber.

A number of factors favour the increase and spread of marsh frogs. Their ideal habitat is warm wet lowlands, with a preponderance of slow-moving deep water and we have no shortage of that. There is a constant food supply and our climate is getting warmer, giving marsh frogs the opportunity of an extended range of distribution. Being primarily aquatic and having toxic skin secretions that make them and their tadpoles taste revolting, marsh frogs have few predators other than herons, little egrets and grass snakes. When basking on the edge of water they are constantly alert and dive for safety at the first hint of terrestrial danger. Pollution and habitat destruction through agricultural reclamation were threats during the eighties, but conservation awareness has removed this in both cases.

Some wildlife organisations insist that marsh frogs occupy an ecological niche that poses no threat or habitat competition to our native amphibians. I am certain they are wrong. Marsh frogs are predators and their increasing numbers must impact, sooner or later, on existing biodiversities. The fact that Phil has not seen a common frog on the inland marshes at Cooling for the last eight years, is conclusive in my view. The history of damage to the ecology by introduced exotic species looks about to be repeated. Except, that marsh frogs are edible and France imports 3,500 tonnes of frogs’ legs per annum from Eastern Europe. It’s just a thought.

Mad March Hares

The late train from London gets into Newcastle at midnight and, barring mishaps, the drive home takes another hour and a half. The last part of the journey is on a tiny back road that winds its way along the edge of the moors, with open hill on one side and fields of the marginal upland on the other. Coming back under a brilliant full moon the other night, with the windows open and lights off, listening for the first sound of spring – the exultant yapping of oystercatchers, I rounded a corner by a windbreak of beech and larch trees to find a company of six brown hares in the middle of the road. Two were engaged in a classic ‘mad March hare’ pose – nose to nose like sumo wrestlers, the others crouched, watching in eager anticipation.

Nor did the audience have long to wait. The protagonists sprang upright and engaged briefly in an exchange of blows with their forefeet, turned and tore down the road shoulder to shoulder. They stopped abruptly and jumped over each other kicking with their hind legs, boxed again and rushed back towards me. All six swirled up and down the road as the two bucks leapt and pranced. They gambolled, chased, kicked and boxed in a frenzy of energy before the whole lot swarmed over a dry-stone wall and careered off down the side of a field. Depending on the weather, brown hares breed at any time of the year and the exuberant lunacy that afflicts them during March must have as much to do with their reaction to the start of spring growth and certainty of summer’s warmth, as any urge to rut.

There are three species of hare in the British Isles, the blue or mountain hare which is indigenous, turns from chocolate brown to white in winter and lives on high moorland. The larger, lowland brown hare which was introduced and the Irish hare, a recognised species in its own right, exclusive to Ireland. These combine some of the characteristics of both, being larger than a mountain hare with a coat that turns partially white in winter. Blue hares can be found on high ground across northern Europe and the Arctic regions. Brown hares have a natural distribution that extends across the whole of Europe to central Asia and were introduced during the 1800s for sport to North and South America, Australia and New Zealand.

No other animal is more surrounded by myths and legends or commands such respect among sportsmen than the hare. Most of it attached to brown hares, partly because they are bigger, faster, more extreme in every way and infinitely better eating than their mountain cousins, but also I suspect, because they played such an important role in Celtic religion. Oestre, the pagan goddess of dawn, fertility and rebirth, had a hare as her favourite animal, light bearer and attendant spirit. They were also the symbol of Andrasta, patron goddess of the Anglo-Saxon Iceni, to whom hares were periodically sacrificed, which would seem to contradict the accepted belief that the Romans were the first to introduce brown hares to Britain. Paradoxically, the wildest of all animals can be easily tamed, if caught young enough and the Celtic ruling classes liked to keep them in their houses as a sort of living connection to the gods. Boadicea is reputed to have careered into battle with the family pet stuffed inside her blouse.

Solitary and nocturnal, brown hares are the fastest and most agile European animal, capable of speeds of 65 kph. They can turn on a sixpence in full flight and jump over 6 metres with ease. This in itself was enough to command respect from early people but their behaviour, which sometimes appears almost humanly irrational and a hideously childlike scream when caught or injured, convinced them that hares were more than simply animals. As surface dwellers, hares rely on speed, eyesight and acute hearing for protection, and have developed elaborate defensive tactics to disguise their scent from predators. Hares feed at dusk and dawn, lying up by day and eating the soft faeces from the previous nights’ feed. When leaving or approaching their form, they double back and forth, making sudden leaps and 90-degree turns to break up the scent line.

For centuries, there was a common belief that hares were hermaphrodite and both sexes bred. This was disproved in the nineteenth century, but what is almost unique, is their ability to be pregnant and conceive at the same time. Does can have four litters of between two and four leverets a year and unlike most young animals that are born blind, bald and defenceless, these have fur and can see immediately. Once the birthing process is over, the doe scrupulously cleans each one and moves them to separate hiding places where they wait, silent and immobile for their daily feed. About an hour after sunset, breaking her scent trail in the usual way, the doe suckles each leveret in turn. Once fed, she rolls the little animal on its back and stimulates the urinary area with her tongue, ingesting any discharge to ensure it remains scent free for the next twenty-four hours before moving them to new sites. Leverets become independent of their mothers after a month.

Under Norman Forest Law, hares were elevated to be one of the five noble beasts of venery, joining the hart, hind, boar and wolf. The Normans were great hound men and loved hunting. Deer, boar and wolves provided speed and drama, but for the complicated science of hound work there is still nothing to beat a hare. They remained fiercely protected by successive game laws, until suddenly demoted to vermin by the Ground Game Act of 1880. Nearly 200 years of agricultural improvements and the small field mixed farming policy of the time, providing an ideal habitat and food range, had led to a dramatic increase in hare numbers – a conservative estimate of the winter population exceeded 4 million. With the right to take game restricted to landlords, tenant farmers struggling to survive decades of agricultural depression lobbied Parliament to be allowed to protect their crops at any time and by whatever means. Hare numbers dropped so alarmingly in the decade following the Act, that a feeble effort to stop the decline, the Hare Preservation Act – which simply banned the sale of hares between March and July, was passed in 1892. It has been left to the sporting community to give hares the courtesy of a closed season.