Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Birlinn

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

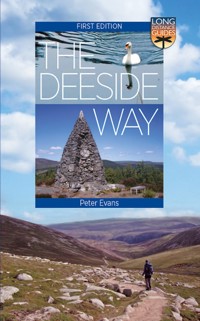

The Deeside Way is a long-distance path running for 66km (41 miles) from Aberdeen, the oil capital of Europe, to Ballater in Royal Deeside in the Cairngorms National Park. Mainly following the course of old Royal Deeside Railway line, it is suitable for cyclists as well as walkers. There is much to be seen along the Way of scenic beauty, historical interest and thriving wildlife. There are fascinating links to the Romans, to Queen Victoria and Balmoral and even to bodysnatchers! This new Guide covers all of these, with a wealth of practical information on preparation for the walk, accommodation, transport and much else. As well as describing the Way itself, Peter Evans includes six additional walks in and around Deeside, varying from short low-level walks to mountain summits.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 148

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

THEDEESIDEWAY

Peter Evans

First published in 2021 by Birlinn Ltd

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

Text © Peter Evans, 2021

Photographs © Peter Evans unless otherwise acknowledged

ISBN: 978 1 78027 590 1eBook ISBN 978 1 78885 209 8

The moral right of Peter Evans to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Printed in China through World Print Ltd

CONTENTS

Walking and Cycling the Way

The Deeside Line

Useful Information

Other Long Distance Routes in Aberdeenshire

Aberdeen: The Granite City

The River Dee

Stage 1, Aberdeen to Peterculter

Stage 2, Peterculter to Banchory

Stage 3, Banchory to Kincardine O’Neil

Stage 4, Kincardine O’Neil to Aboyne

Stage 5, Aboyne to Ballater

Walks around Deeside

The Balmoral Cairns

Burn o’ Vat and Culblean

Loch Kinord

Glen Tanar

Bennachie

Lochnagar

Beyond Ballater: Braemar to Aviemore

Index

The riverside path at Banchory on the Deeside Way.

WALKING AND CYCLINGTHE WAY

The Deeside Way stretches for 66km (41 miles) from the city of Aberdeen to Ballater in the Cairngorms National Park. It is based for the most part on the former railway line which ran along this route for around a century until its closure in the 1960s during the Beeching era. For walkers and cyclists, the Deeside Way provides varied scenery, from the urban, yet leafy confines of Aberdeen and its suburbs to the hillier, more dramatic countryside further west into Aberdeenshire.

The route is well waymarked throughout and level in the main, with the exception of the stretch between Banchory and Aboyne. Here it deserts the old line and there are more ups and downs on forest tracks and paths, though it is never very challenging for anyone with a reasonable level of fitness. So as long distance routes go, it’s at the more amenable end of the spectrum and can therefore be tackled by a broader range of walkers, who might be daunted by the prospect of the West Highland Way, for example.

Cycling charity Sustrans is a funding partner and takes on the task of looking after signage, with volunteers undertaking minor maintenance work. It means that blue Sustrans Cycleroute 195 signs appear along the length of the Way, as well as Deeside Way markers, making route-finding clear and easy.

Aberdeen City Council is responsible for the management of the Way as far as Dalmaik, with Aberdeenshire Council having responsibility for the remaining sections to Ballater. The Cairngorms National Park Authority is developing plans for an extension of the Deeside Way from Ballater to Braemar, but it will be some time before this comes to fruition due to protracted negotiations with landowners.

For the purposes of this guide the route has been divided into five sections, with accommodation readily available for the most part. Kincardine O’Neil is more difficult, though self-catering is a possibility. Otherwise it’s a case of staying nearby and returning to the village on the bus. The division into five sections is designed to enable you to get the most out of what there is to see along the Way, with much of interest within easy striking distance of the route itself and further afield.

A bridge takes the Way over Holburn Street, near Duthie Park.

However, for the more ambitious or those who have less time available, sections can be joined together to make longer days – for example Aberdeen to Banchory and Banchory to Aboyne, though this turns the Way into more of a route march, which is not the best way to enjoy it.

Another possibility is to make use of the excellent and frequent bus services which run between Aberdeen and Ballater. For walkers this provides the option to do the route in stages from one or two bases – Aberdeen and Banchory for instance – using the bus to return to your start point. This also makes any problems with finding accommodation easier. It’s more plentiful in the city and larger towns.

The Deeside Line

The railway through Deeside began life on 7 September 1853, when the line opened between Aberdeen and Banchory. It was extended to Aboyne six years later, and another extension in 1866 took it as far as Ballater, which became the terminus for the rest of its existence. The line was key to the development of what has become known as Royal Deeside due to its association with the royal family. Originally the entire route ran on a single track with passing loops, but between 1884 and 1899 a double track was laid to Park, near Drumoak. This led to the introduction of a popular suburban commuter service between Aberdeen and Peterculter, affectionately nicknamed the ‘subby’.

Initially the railway as far as Aboyne was operated by the Deeside Railway Company and to Ballater by the Aboyne and Braemar Railway Company. They joined forces in 1876 to form the Great North of Scotland Railway, which was itself amalgamated in 1923 with other east coast railways to form the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). British Railways finally took charge of the Deeside line in 1948 until its closure.

A variety of steam locomotives travelled the route over the years, the best remembered being the ‘Great North’ 4-4-0 class. The sole surviving loco, Gordon Highlander, is now an exhibit at the Glasgow Transport Museum. Well before its time, an electric battery railcar, dubbed the Sputnik by locals, was used experimentally for a number of years from 1958.

In its heyday, the Deeside line stood out as one of the finest rural railway lines in the country. Views from the trains were outstanding, and the service carried a wide variety of passengers from across the world. British and foreign royals, including Queen Victoria, used the line, along with heads of governments – even the Russian Tsar. At the other end of the scale were young adventure seekers with their rucksacks and bicycles, heading for the Cairngorms and the surrounding countryside to soak up the scenery and revel in the challenges of some of Britain’s highest mountains.

The use of the Deeside line by members of the royal family and important visitors, who made their way to and from the royal residence at Balmoral Castle, inevitably gave it added kudos and attracted tourists.

It also provided a cheap form of transport for people holidaying on Deeside and acted as a convenient source of public transport for those needing to get to and from Aberdeen. Originally it was intended that the line would run all the way to Braemar, but Queen Victoria’s fears about her privacy at Balmoral being invaded meant this never came to pass.

Information board for Holburn Station on the Deeside Line.

The platform and former station house, now a holiday home, at Cambus O’May.

Its demise came about following the highly controversial 1963 report by Dr Richard Beeching, which led to the axe falling on 4,500 miles of railway line and 2,128 stations throughout Britain to save money, despite vociferous protests. The Deeside line passenger service ceased in February 1966 and the freight service later the same year.

Restored for trains

A short stretch of the Deeside line – from Milton of Crathes towards Banchory – has been restored, thanks to the work of volunteers, and it’s possible to travel along this section, with efforts being made to extend it as far as Banchory. Trains run between April and September, with an occasional service at other times. A similar line, again run by volunteers, links Aviemore with Boat of Garten in the Cairngorms. It’s a popular mode of travel for anyone wanting to visit the RSPB’s excellent osprey reserve and visitor centre near Boat of Garten.

USEFUL INFORMATION

GENERAL WEBSITES

The official Deeside Way website is www.deesideway.org. Aberdeen City Council look after the early part of the Deeside Way: www.aberdeencity.gov.uk; the rest of the route comes under the jurisdiction of Aberdeenshire Council: www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk.

Other Deeside Way partners are:

Forestry and Land Scotland (formerly the Forestry Commission): www.forestryandland.gov.scot.

NatureScot (formerly Scottish Natural Heritage): www.nature.scot.

Sustrans: www.sustrans.org.uk.

Cairngorms National Park Authority: www.cairngorms.co.uk.

Scottish Enterprise: www.scottish-enterprise.com.

BIKE REPAIR SHOPS

Aberdeen: Alpine Bikes, 70 Holburn St. (01224 411455); Edinburgh Bicycle Co-operative, 458-464 George St. (01224 632994); Evans Cycles, 876 Great North Road (01224 444020); Holburn Cycles, 198 Holburn St. (0845094 8863); Halfords, Bedford Road, Kittybrewster (01224 276811) and at 2 Balnagask Road (01224 875526).

Banchory: Banchory Cycles, Station Road (01330 820011).

Ballater: Cycle Highlands, The Pavilion, Victoria Road (01339 755864); Bike Station, Station Square (01339 754004).

ACCOMMODATION

There are plenty of B&Bs and hotels along the route. In Aberdeen, several are close to the start of the Deeside Way. See: www.visitabdn.com/plan-your-trip/where-to-stay and www.visitscotland.com/accommodation for further information.

CAMPSITES

There are sites at Aboyne, Ballater and Maryculter (near Peterculter).

Wild camping is not really feasible for much of the route. In any case, out of politeness it’s wise to ask the landowner’s permission if wild camping is considered.

PUBLIC TRANSPORT

Buses run frequently between Aberdeen and Ballater seven days a week. The relevant services are Stagecoach 201 and 202. Website: www.stagecoachbus.com.

For timetable information call: 0871 200 22 33

Live service information line: 01224 597587

Other Long Distance Routes in Aberdeenshire

The Tarland Way runs for 10km (6 miles) from Aboyne, northwest to Tarland.

The Gordon Way partly follows the old peat extraction routes in the forests around Bennachie. It currently runs for 18km (11 miles) from the Bennachie Visitor Centre west to a car park at Suie, with plans for an extension to Rhynie.

The Formartine and Buchan Way uses the route of a former railway line from Dyce, on the edge of Aberdeen, to Maud in the north, where it divides. The eastern arm goes to Peterhead and the northern arm to Fraserburgh. From Dyce to Fraserburgh is 64km (40 miles) and the extension from Maud to Peterhead is 21km (13 miles) long.

More information including detailed route cards for both these latter routes can be found at www.aberdeenshire.gov.uk/paths-andoutdoor-access/long-distance-routes.

Aberdeen: The Granite City

Situated between two mighty rivers, the Don to the north and the Dee to the south, Aberdeen is one of Scotland’s major conurbations and is currently home to around 230,000 people in the local authority area, encompassing the city and its extensive suburbs.

With heightened fears about global warming and the release of CO2 into the atmosphere, resulting in increasing moves towards the use of renewable energy and less dependence on fossil fuels, Aberdeen still ranks as the offshore oil capital of Europe. A visit to its busy port bears testament to that, with huge vessels coming and going and a feeling of vitality about the place. It also acts as a ferry port for services to Orkney and Shetland. The fate of the city changed dramatically in the mid-twentieth century with the discovery of North Sea oil. Experimental drilling in 1970 led to land being made available for oil-related industries and industrial estates were built to service the anticipated explosion of activity.

The River Dee at Aberdeen Harbour, busy with shipping traffic.

The first oil from the North Sea came onshore in 1975 and the industry brought considerable prosperity, both to those who worked in it and to the city itself. Skilled offshore engineers could earn up to £1,000 a day and property prices went through the roof, though major changes have taken place over the years to reverse this pattern.

While newer enterprises such as information technology have taken up some of the slack, they can never replace the wealth Aberdeen enjoyed in the heyday of the oil industry.

In summer 2018, a constant reminder of the challenge to oil production emerged in the form of a wind farm just off the coast in Aberdeen Bay. The 11-turbine development attracted much controversy in the planning stages, due to opposition from no less a figure than American President Donald Trump. He claimed it would spoil the view from his Menie Estate coastal golf course – itself only created after a great deal of wrangling and acrimony, with the businessman, still to be elevated to the presidency at the time, accused of riding roughshod over opponents to his plans. Mr Trump resorted to law to block the wind farm, taking his case all the way to the UK Supreme Court in London after failure in the Scottish courts, but ultimately lost his battle.

The oil boom through the 1970s and onwards displaced more traditional trades such as fishing, papermaking, shipbuilding and textiles. From the mid-eighteenth to the mid-twentieth century, another enterprise involved the quarrying of grey granite, which was used in many of the city’s buildings and gave Aberdeen its nickname as the Granite City. Much of the material for the city’s buildings came from the giant Rubislaw quarry, located on Rubislaw Hill to the west of Aberdeen.

Granite produced around Aberdeen is shot through with mica crystals which glint in the sunlight, providing the city with another name – the Silver City with the Golden Sands. The latter is derived from the long sandy beach stretching all the way from the Dee estuary north along the esplanade to the mouth of the Don – popular with Aberdonians and visitors alike for relaxing and even surfing when the conditions allow.

Rubislaw Quarry.

RUBISLAW QUARRY

After it was opened in 1740, an estimated six million tonnes of granite were excavated from the quarry over a period of 200 years. It provided granite not only for buildings in Aberdeen but also for the balustrade of London’s Westminster Bridge, built from 1811 to 1817.

Other buildings using Rubislaw granite include the Tower of London, Leeds University, the Halls of Justice in Swindon and Dumbarton’s Municipal Buildings. In 1964, stone from the quarry was used for the imposing memorial to Robert the Bruce at Bannockburn.

The quarry closed in 1971 – the last in Aberdeen to do so. One of the largest man-made holes in Europe, 142 metres deep with a diameter of 120 metres, it is currently filled with water.

Aberdeen is home to two universities – the University of Aberdeen, founded in 1495, and Robert Gordon University, awarded university status in 1992 – and has won the Britain in Bloom competition a record-breaking 10 times. The bustling city centre, based around Union Street and the Union Square shopping and leisure complex, which opened in 2009, encompasses modern shops and offices and a variety of bars and restaurants.

Famous people connected to the city include Manchester United legend Denis Law, singers Annie Lennox and Emeli Sandé and virtuoso percussionist Dame Evelyn Glennie. Paul Lawrie, the last Scottish golfer to win a Major with his victory in the Open Championship at Carnoustie in 1999, was born in Aberdeen.

The modern, vibrant city of today is a far cry from Aberdeen’s origins, when prehistoric villages grew around the mouths of the Don and Dee around 8,000 years ago. By the early twelfth century Aberdeen had grown into a town with a busy port, exporting salted fish, hides and wool. In the early Middle Ages there were actually two settlements, Old and New Aberdeen, which later merged, but remained legally separate until they were finally unified in 1891.

The Church, Catholic at this time, exercised great power and its presence was everywhere. St Machar’s Cathedral was built in stages in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The Church ran the only ‘hospitals’ during this period, with records of the poor being given food and shelter. In 1363 a leper hospital was founded outside Aberdeen on Spital Hill, where monks looked after the lepers as best they could. The dreaded disease slowly died out as time went on.

King Robert the Bruce had a close association with the city and is commemorated by a statue outside the city council’s imposing granite headquarters at Marischal College.

During the Wars of Scottish Independence, Aberdeen had a castle which was occupied by an English garrison. Bruce and his men laid siege to the fortress in 1308, burning it down and killing its inhabitants. He was seemingly helped in the task by local people, who were rewarded for their loyalty with the gift of a royal hunting forest. The secret password Bon Accord, said to have been used in the conflict, has been incorporated into Aberdeen’s coat of arms.

In 1350 the town was stricken by the Black Death, which killed thousands across Britain and wiped out around half the population of Aberdeen. Then in 1401, another disease called the ‘pest’ – possibly typhoid – killed many more. However, Aberdeen bounced back, growing into a large town by the standards then, with a population of about 4,000 as the Middle Ages came to an end. By the early seventeenth century numbers had reached between 8,000 and 10,000.

Important buildings from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries include Provost Skene’s House, named after Sir George Skene, who was provost of Aberdeen from 1676 to 1685. In 1593 Earl Marischal founded Marischal College and the Tolbooth was erected after 1615, with a steeple added in 1629.

With a history spanning more than 750 years, Aberdeen Grammar School is another notable educational institution in the city and one of the oldest grammar schools in Britain.

Aberdeen continued to be an important port and in 1607 a bulwark was built along the south of the estuary to allow the harbour to be made deeper by tidal movements. In 1618 a large rock that blocked the harbour was removed to improve passage for vessels.

Things took a turn for the worse again in September 1644 when the Marquis of Montrose led his royalist troops against Aberdeen, plundering it and killing many of the townspeople, but there was revenge in 1650 when Montrose was captured and executed. One of his arms was sent to Aberdeen and put on public display.