20,39 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: ONE

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

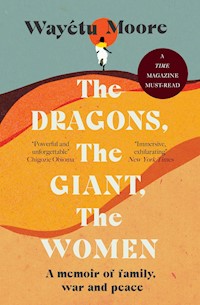

FINALIST FOR THE NATIONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE AWARDA NEW YORK TIMES BOOK OF THE YEARA TIME MUST-READ BOOKWhen Wayétu Moore turns five years old, civil war breaks out in her home country of Liberia. Separated from her mother in far-away New York, Wayétu is forced to flee with her family on foot, until a remarkable rescue by a rebel soldier.But even with her family reunited in the safety of her adopted home, America, Moore finds herself – as a Black woman and an immigrant – in a new kind of danger. Will she forever be that girl still running?PRAISE FOR The Dragons, the Giant, the Women'Immersive, exhilarating… an essential voice' New York Times'As the migrant experience becomes crushingly more common around the world, stories such as The Dragons, the Giant, the Women remind us just how personal and painful these displacements are' Elle, Best New Summer Books'Powerful, utterly convincing and unforgettable' Chigozie Obioma, author of The Fishermen'An urgent narrative about the costs of survival and the strength of familial love' TIME'A propulsive, heart-rending memoir of love and war and peace… marries the language of fantasy with the texture of reality' Namwali Serpell, author of The Old Drift

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Ähnliche

“Deft and deeply human, Wayétu Moore’s The Dragons, The Giant, The Women, had me pinned from its first page to its last … This is an astonishment of a book” Mira Jacob, author of Good Talk

“Absolutely breathtaking. In extraordinary prose and with remarkable restraint, Wayétu Moore has created both a riveting narrative of survival and resilience and a tribute to the fierce love between parents and children” Mary Laura Philpott, author of I Miss You When I Blink

“Wayétu Moore stretches the art of writing on family, war and movement to mythical heights with her otherworldly poeticism” Morgan Jerkins, author of Wandering in Strange Lands

“Wayétu Moore takes an unflinching look at survival in her unforgettable memoir, which traces her family’s journey fleeing Liberia on foot in the midst of a civil war to their experiences, years later, as immigrants living in Texas”TIME, Books of the Year

“A nuanced and haunting memoir”LitHub

“Riveting and beautifully written … The extraordinary power of [The Dragons, The Giant, The Women] resides not only in [Wayétu Moore’s] flight but in her survival”National Book Review

“Building to a stunning crescendo, the pages almost fly by. Readers will be both enraptured and heartbroken by Moore’s intimate yet epic story of love for family and home”Publisher’s Weekly, starred review

iii

The DRAGONS, The GIANT, The WOMEN

Wayétu Moore

v

For Junior & David.

Whatever you are, I am.

vii

Take your broken heart, make it into art.

— carrie fisher

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I have tried to recreate events, locales, and conversations from my memories of them. In order to maintain their anonymity, in some instances I have changed the names of individuals and places, and I may have changed some identifying characteristics and details such as physical properties, occupations, and places of residence.

The DRAGONS, The GIANT, The WOMEN

CONTENTS

RAINY SEASON

ONE

Mam. I heard it again from another room, as I always did when the adults were careful not to mention her name around me, as if it was both a sacred thing and cause for punishment, and I ran toward it. Mam is what they called her then. Down hallways, across the yard, behind closed doors—her name the most timid kind of ghost. “Mam so beautiful” or “Mam used to go there plenty” or “That’s not the way Mam cooked it” they would say quietly, cautious not to raise the drapes with the wind of their voices. And I would stumble in, wanting to catch them in the act, to give me that word again for so long that I fell asleep to the sound of it. Startled by my tiny body, they would stop and ask if I had finished my lessons or if I wanted a snack.

Once when it was raining, I heard her voice outside. An Ol’ Ma, a grand-aunt maybe, told us that all of our dead and missing were resting peacefully in wandering clouds, and when it rains and you listen closely you can hear the things they forgot to tell you before leaving. Mam was not dead, they said, but I stumbled into the rain and stood beside the rosebush where I was sure I had heard her voice, full of laughter and long ago, singing those forgotten things.

“Tell me where she is,” I would ask.6

“In America, you girl. I told you. In New York,” they would say.

“Are you sure?” I asked to be certain. “When will we see her again?”

“Soon,” they said.

“Can I go there?” I asked, though I knew the answer.

“Why would you want to go there, you girl?”

They convinced me that Liberia’s sweetness was incomparable—more than a ripe mango’s strings hanging between my teeth after sucking the juice of every sticky bite, the Ol’ Ma’s milk candy that melted on my tongue, sugar bread, even America—none a match for the taste then, of my country. This was all I knew of my home then—that I lived in a place that made words sing, so sweet. Yet it was without my mother.

In those years, turning five years old tasted like Tang powder on the porch after supper. Little boys drove with their Ol’ Pas, a grand father or other old man with pupils eclipsed with a dwelling blue, to the Atlantic, to fish facing the sunset. Little boys sat in parlors of opaque tobacco smoke as they watched Oppong Weah kick soccer balls into checkered nets against Chelsea. Little boys could now walk alone to those junction markets that sold everything from bushmeat to shoestring, to buy the plantains and eggplant driven from Nimba’s farms for their nagging Ol’ Mas.

Little girls could now help to wash sinks of collard greens in front of kitchen windows that faced pepper gardens. Little girls could draw water from neighborhood wells and balance them on their heads, full of braids and restless musings, all the way back to their houses as the sun lingered at the edge of the sky to make sure they had safe walks home.

I turned five that day and the greens felt soft between my hands. They only let me wash them once, and afterward I was pushed away and told to leave the cooking to the cooks.

“You will have plenty time to wash greens, you girl,” Korkor said, laughing from the hollow between the wide gap of her two front teeth.

“But I want to wash them longer,” I said.

She picked me up from the stool in front of the sink and carried me to a table where a cake tempted me from the middle of snack plates.7

“Look, you will spoil your fine dress!” she said, straightening the purple linen.

“The Ol’ Pa will be vexed if you spoil your fine dress,” she rambled, and returned to the sink to complete the cleansing and preparation of my birthday greens. I did not believe that my grandfather would be angry with me if I spilled water from the greens on the dress he had sewn for my birthday. No, Charles Freeman would be proud that he would have one more granddaughter whom he could send for water from the well in Logan Town where he lived with Ol’ Ma.

It was a famous well, mentioned in many of Ol’ Ma’s stories about Mam’s childhood and those memories of her life before us. It was better than the well near their old home further inside Logan Town. Ol’ Pa was a tailor and Ol’ Ma was a shop owner then, and they had moved with other Vai people toward the city, where most settled in Logan Town after a man they call Tubman, the president at the time, gave jobs to rural Liberians. It was 1966.

They say the water well was a ground-level brick structure with concrete lining similar to most wells in Logan Town. It was a hand-drawn well with a bucket that dropped quickly in and out. As the bucket rose, Mam would grab the handle and pull it toward her small body to empty the water into her own plastic bucket. Once, alone in the yard, Mam peeked over the well and sang into it, as they say she always did, and the well threw an echo back up. “Dance with me,” she sang, and the well repeated her words, spitting a familiar voice onto the yard. She laughed, and while raising one of her hands to cover her mouth, Mam lost her balance and fell into the well. Darkness smothered her and the water below swallowed her body. The bucket rose and Mam spat the coldness out of her nose and mouth, gripped the rope, and yelled so that someone would hear her. As the bucket ascended, she heaved what she could out of her system and yelled again, scraping her fingers on the inside walls for something she could hold on to. The bucket fell again, and this time she did not know if she was moving or still, if the darkness was her end; the sunlight was so close and yet it mocked her in the distance. When the bucket resurfaced from 8the water, Mam’s grip on the rope loosened, and when she opened her mouth to yell, nothing came out. She stretched out her hands, expecting to scrape the concrete walls, to fall again and be lost forever in the Logan Town shadows, but instead, as the bucket rose she felt a coarse palm wrap around her right wrist. Her head lay limp on her shoulder as her body was raised out of the well. It was a Ghanaian neighbor, Mr. Kofi, whom Mam was known to taunt through her window as he walked to work every day. “Thank you,” Mam whimpered, barely conscious. From then on, Ol’ Pa made sure he sent at least two daughters or granddaughters to the well.

I turned five that day so I knew that I could now be called to go too.

“But you say I can wash them today,” I said, turning from the pink and yellow birthday fixtures on the table back to Korkor. “You say I can wash them.”

“And I let you wash them, enneh-so?” she said, placing the greens into a bowl on the counter. Korkor wiped her hands on the lappa tied around her waist and came to me. She took my hand and led me to the den and I dragged my feet so that my white dress shoes scraped the floor behind her.

“Torma!” Korkor yelled out. “Torma, come get this girl.”

In the den, Torma sat with my sisters, Wi and K, in front of a game of Chutes and Ladders.

“Come,” Torma said, taking my fallen fingers. “Come play, small girl. Be on my team. I winning,” she assured me.

Torma was a teenage Vai girl from the village of Lai, a third cousin, another caretaker who boarded with us after Mam left. Papa paid for Torma’s education in Monrovia, and she, in turn, took care of my sisters and me in Mam’s absence. Korkor mentioned once that the girls from Lai made good mothers. I cried the night she moved in and told Papa that I did not want anyone else to come be my “mama.”

“She will not be your mama. Mam is coming back. She will be your friend.” When Torma stepped out of Papa’s pickup truck, she was introduced as “your cousin from Lai. Your big sister.” She kept to herself mostly, and alongside Korkor if she was not at the table reading or “taking care of lesson.” Over time the same orange shirt she was wearing 9on the day that I met her became faded and stained with spilled food. Finger paint remained splattered between the buttons, no matter how many times she washed it.

“Look, we winning,” Torma said as I knelt in front of the board game. K, a three-year-old with a charming round face who knew the power of being the youngest of the three of us girls, parked in Torma’s lap as soon as she sat back on the floor. She would turn four in only two months and looked to have been coerced to behaving with a party of her own. She twirled the barrette that stopped one of her pigtails between her fingers and smiled toward Wi, my six-year-old sister who concentrated on the board. The den was decorated with colorful helium balloons and metallic streamers taped neatly onto the folds where our walls met.

“Where my papa?” I asked Torma.

“Your papa outside with Moneysweet and Pastor,” she said, and sucked her teeth as I bounded out of the room and onto the porch deck of our yard.

Papa sat in a deck chair beside the pastor of our church, a man who always gently shook my hand when he saw me. The reflection of their water glasses speckled the plastic table where they sat. It was a warm day, and the leaves of towering palm trees swayed above us amid a vast field of freshly watered grass. A radio rested on the rail of the deck and the exaggerated harmonies, the clashing of cymbals and drums, filled the surrounding yard. Papa’s and Pastor’s smiles bent to the rhythm as it vibrated the metal antennae. Moneysweet sat on a stool near the table and peeled a mango plum with a sharp knife. The sweat from his orange, square head descended both sides of his face in the sun, and upon seeing me he extended a slice of plum in my direction.

“Papa,” I said, whining as I climbed into Papa’s lap. “Korkor say I will wash greens on my birthday and then today she say not for long.”

“You wash greens you will spoil your dress,” he said, repeating Korkor’s warning.

“I will not spoil it,” I insisted.

“Wait, small small,” he said. “After your party you will wash the greens.”10

I bit down on the ripe plum wedge, and the juice from it oozed out and followed the lines of my lips and jaw until the bottom of my face was completely sticky and wet. I worried that Papa would see me and send me back inside to Korkor or Torma to wipe my face, but he and Pastor had already resumed a conversation about a man whose name I heard at least once a day.

“But Doe has spoiled the country. Liberia spoiled-oh,” Pastor said, shaking his head.

“It’s not spoiled. Two more years the man’s gone. A new president will come.”

“He will rig the thing like he rigged the last one. Everybody fighting, everybody wants to be president. Everybody says they president,” Pastor continued.

“Yeh, the country spoiled. Sam Doe spoiled it,” Moneysweet agreed from the corner of the deck before shoving another slice of plum in his mouth.

I asked Ol’ Ma who this man was, Samuel Doe, whose name I heard once a day, and she told me he was president of Liberia. Every time I listened to people talk about this man, it reminded me of the Hawa Undu dragon, the monster in my dreams, the sum of stories I was too young to hear. The Hawa Undu dragon was once a prince with good intentions, who entered the forest to avenge the death of his family, all buried now in the hills of Bomi County. He was a handsome prince, tall with broad shoulders, high cheeks, and coarse hands marked by the victory of his battles. He entered the forest and told the people that he would kill the dragons who left mountains of ashes in Buchanan and Virginia, who left poisoned eggs in Careysburg and Kakata. But the prince became a dragon himself. One with asymmetrical teeth, taloned elbows, and paper-thin eyes. One with a crooked back, coarse like the hollows of the iron mines where many sons were still lost, always dying. One rich enough to fly, yet too poor to know where to go. He humbugged the animals, killed for food, forgot his promises. And now, Hawa Undu was president of Liberia, once a prince with good intentions. Ol’ Ma said everybody was talking about him because there was another prince who wanted to enter the forest and kill Hawa Undu, to 11restore peace. This prince was named Charles, like my Ol’ Pa. Some thought he would be the real thing—that he could kill Hawa Undu and put an end to the haunting of the forest and the spirit princes who danced throughout—but others feared he would be the same, that no prince could enter the forest and keep his intentions. The woods will blind, will blunder. Hawa Undu would never die.

“You see the Burkina Faso rebels them have entered the country, and come start killing Krahn people left and right because Doe is Krahn man. You don’t think they will kill Doe? They going for him,” Pastor said, rubbing his chin.

“You hear from Patrick?” Papa asked after a moment.

“No, the people say he went and collected his Ol’ Ma from the bush and went to Ghana,” Pastor said.

“His house still there?”

“They looted it, I hear. But they didn’t get much,” Pastor continued.

“Mr. Patrick?” I asked. My father nodded, reluctantly. “Mr. Patrick is in Ghana?”

To this he did not respond, and I wondered about Mr. Patrick and Ms. Genevieve, his wife, and their two sons. Ms. Genevieve always gave us milk candy when we visited their house in Sinkor, which was so big that ten women were able to fit their markets in the front.

“All the Gio and Mano people running.”

“Patrick was safe, my man. Doe’s people were not looking for him. They know he was not giving money for no rebel business,” Papa said.

“Doe’s soldiers don’t know nothing. They see Mano man, he gone.”

“Hm. Everybody say they will kill man in power and lead better. Say they want kill Krahn man ’cause Krahn man not good president,” Papa argued.

“And Krahn man want kill Gio man and Mano man,” Moneysweet added. “For what?”

“And Gio man want kill Mandingo man,” Pastor said loudly as he pointed at Moneysweet.

“And every man want kill Congo man,” Papa said, almost singing. “Quiwonpka tried and now the man dead, enneh-so?”

Moneysweet laughed, wiped his sticky hands on his jeans, and stood 12up from the stool where he sat, shaking his head. He vanished into the house and reemerged with a napkin that he used to wipe my face.

“You will leave, Mr. Moore?” Moneysweet asked Papa.

When I asked my teacher what happened to Kelly, what happened to Josephine, what happened to Wiatta, what happened to Gerald, what happened to Saa, she murmured, America. I did not believe her until I stopped seeing them. I did not have a chance to share what I wanted to tell Mam in case they saw her.

“No. Me, I’m staying. The people are not serious,” Papa said. “When the people realize it’s a waste of time trying to push the man out and let him just go on his own through the next election, the country will go back to normal.”

“Hmph. He will not go on his own-oh. He will not go,” Pastor said matter-of-factly.

Through a green and clear Liberian April, a car approached us from the flat road with shoulders and elbows sticking out of its windows. When it parked in front of the deck, I stood up when I recognized Mam’s parents, my Ol’ Ma and Ol’ Pa, whom we called Ma and Pa. My uncle was with them also, and a cousin and his mother. I stood up from where I sat with Papa and ran to Pa, a towering man with a round bald head, whose face I could barely see when I looked up and the sun was its highest.

“Birthday geh,” he said, picking me up with great difficulty as soon as he stepped out of the car.

“Look, my dress,” I said into his face.

“It looks good,” Ma said, touching the lace cloth that lined the hem.

My sisters, who heard their voices from inside, bolted toward Ma and Pa, nearly bowling them over with the charge.

The men settled on the porch with Papa and Pastor. They were mostly dark and stout men who all appeared serious, only to collectively descend into an abyss of laughter at the right word or joke at an unfortunate person’s expense. Korkor walked onto the deck and told the guests that the food was ready, then she whispered something into Ol’ Ma’s ear. Beyond the den and around the dining room table, my 13family was gathered behind a cake with burning candles coming from its face. They noticed me and began to clap and holler, and Ol’ Ma pushed me toward the table and cake from behind. It became quiet and I was sure they would all sing.

“Where is Mam?” K asked.

Mam. It remained silent for a moment. It was a moment like a box packed tight and closed for so long that when it was finally opened its contents rushed out. I did not wait for them to bellow the birthday song, but ran into my room and stared out of the window. Mam. Korkor came behind me, and Papa, but none would pull me away. Not the smell of fresh greens, not my Ol’ Ma, not my Ol’ Pa. Not the cake and streamers, or turning five. I remained near the window waiting. I needed it to rain again. I wanted to hear Mam sing.14

TWO

In the months after Mam left Liberia for New York, we talked to her every Sunday. She sounded the same to me then, though once or twice her voice disappeared while she spoke. I inhaled the heavy silence, hoping that some of her would seep through the phone so that I could lay my head against it.

“I will soon be back, yeh?” she would say.

After moving into the house with palm trees, I found that her smell had moved with us, followed me as I, on so many Saturday afternoons, had trailed her around the apartment in her red high heels that dragged underneath my feet. In her closet, in her room, in the kitchen, even Korkor smelled like her—the calming blend of seasoned greens and rose water.

Every day our driver, a short, chubby man with a blunt line of gray hair an inch above each ear, picked us up from school. Torma met him at the end of the road to walk us home. From the main road we could see our house dancing in the heated rays of the sun, a drawing that grew bigger and more real with each step. We stumbled out of the car in uniform plaid skirts and small pink backpacks. Torma waved at our driver as his tires blew a whirl of dust into the air when he drove away. 16

“Come,” Torma said, turning around to us. “Surprise for you all inside.”

Upon hearing the word, we sprinted down the dusty road. It was dry season in Monrovia and the sun strained its eyes, burning arms and feet as we ran. Moneysweet waved from a rosebush in the front yard and we waved back before nearly tripping over our feet into the house.

“Surprise today,” he said as we climbed, one step at a time, up the porch stairs. He laughed and shook his head at our excitement.

Inside, there was no father or grandparents. The foyer was empty. We searched our rooms and found nothing of importance or shock, so we approached Torma in the hallway.

“You girls fast,” she said.

“Where’s the surprise?” Wi asked.

“In the den,” Torma said. Before she finished the sentence, we were in full stride through the front hallway toward the den.

In the den, near my mother’s scented couch, there was a large brown envelope with black writing and stickers on it. Anytime something like this sat on the table when we came home, it meant that Mam had sent something for us.

“It’s from New York! It’s from New York!” we chanted and took turns waving the large envelope in the air.

The front door opened and after a short set of footsteps, Papa walked into the den.

“Mr. Moore, you here?” Torma asked, quickly standing. He motioned for her to sit down and allowed us to jump around the room before throwing our arms around his neck.

“I got in early. It came, enneh-so?” Papa asked. Torma nodded. She walked out of the den and returned with a pair of scissors. She cut the tape on the envelope and opened it. I reached inside.

“What is this?” I asked disappointedly. Two small boxes that looked like video cases lay inside the box with a letter.

“Movies,” Papa said as K pinched his cheeks, already distracted by his presence from the mysterious box that she was shouting over only a few seconds earlier. 17

“Ma-Ma-lawa?” K asked in his lap.

“No, not that movie,” he said. The Malawala Balawala country dancers were K’s favorite. The people on the two boxes I held looked different. On one box there was a girl with white skin and a blue dress, a little dog, and three Gio devils that were connected at their hips. The other was a woman with white skin and white hair with her hands stretched out in grass. I was confused.

“Read it,” Papa said.

“Wiz-ard of Oz,” Wi read from the box with the Gio devils.

“Sound of Mu-sic,” she read from the other box.

I was still confused.

“Why do they look like that?” I asked.

“Like what?” Papa asked.

“Like, sick. White, an—” I said.

“They don’t look sick. They just have different color skin. Like the missionary woman, Sis’ Walton,” Papa said.

“What?” I asked, disappointed.

“Like our neighbors,” he said.

“The neighbor not white,” I said.

“No,” Papa continued. “But he is different color.”

Torma held her hand to her mouth and giggled.

Papa stood up and took the movie from my hand. He put it in the VCR and turned on the television. He stood for a while in front of the television and then walked behind it and fidgeted with a long black cord.

“This cord is spoiled. Who spoiled the cord?” he asked, lifting the stretch of cord where tiny red and green wires peeked distortedly out of their leather shield. I would have suggested that it was K and her incessant viewing of the Malawala Balawala country dancers, but I knew Papa would call it “frisky” and I did not want to risk watching the white people.

“Mr. Moore, I can go to the store,” Torma suggested.

Papa shook his head as Moneysweet walked through the den door.

“Mr. Moore, I’m finished,” Moneysweet said, still sweating. 18

“Moneysweet, you can go to the market for VCR cord?” he asked.

“Sorry, Mr. Moore, I’m meeting friends tonight,” he said.

Papa nodded and reached his hands into his pocket. He paid Moneysweet his daily wages, and Moneysweet walked through the den to his garage apartment.

“Have fun with your surprise,” he said, walking out.

Papa folded his hands.

“I know. Let’s go see if the neighbor has a cord,” he said.

Wi and K jumped out of their seats. I was not so quick to move. This news of our neighbor’s possible “whiteness” both frightened and angered me.

Our neighbors lived behind a tall cement wall crowned with barbed wire. Papa said they blocked off their house like this because the rogues kept coming to steal from them. Their gate was open, so we walked through. When he opened his door, I did not know what to expect. I thought he would be as blue as my skirt or as orange as Torma’s shirt. He was, however, still the same as the last time I saw him.

“Hello, Mr. Moore, girls,” he said, nodding toward us with his syrupy accent. They said hello. I whispered it while inspecting his face for rainbows.

“Hello,” Papa said. “The girls and I wanted to know if you had an extra VCR cord. Mam sent a video from America that they want to watch,” he said.

“Sure, sure, yes,” our neighbor said and invited us into his house. Their den was decorated with porcelain statues and many pictures of their lives and family in China. Bright red drapes hung down to the floor and the gray couches and chairs were covered with plastic. His wife came toward us from the back of their house. She shook Papa’s hand and nodded her entire body toward him multiple times. Our neighbor returned to the room with the cord, and after taking it from him, Papa became distracted by a stack of boxes in the corner. He fidgeted with the cord and stared at the boxes, then at our neighbor in concern.

“You planning to move?” he asked, pointing toward the boxes. 19

Our neighbor put his arm around his wife’s shoulder, squeezing it underneath his fingers.

“Yes, yes, we going back for a while,” he said, and glanced at my sisters and me.

“Why? What about your business?”

Our neighbor removed his arm from around his wife’s shoulder.

“Mr. Moore, can I talk to you? In the sitting room?” he asked. Papa nodded and followed, closing the door behind them.

“Wait here,” his wife said with a voice as soft as feathers. She exited the den and my sisters and I were left standing alone. Behind the door, I heard Papa say Hawa Undu’s name. He did not sound angry, but he was not laughing or smiling. I could tell he and our neighbor were very serious. There were many boxes in the corner. Torma said once that if someone came to remove Hawa Undu the dragon and the people started to fight, they would hurt not only other Liberians but also the Chinese people who were bad to them. And they would go find the Lebanese people, too, and they would hurt the boss man who slapped their sons at work. And they would find the professors who failed them for not being smart, the professors who did not take money for grades. And they would find the people who were rude to them once or twice, and those who had offended them years ago, and they would hurt them.

His wife returned to the room with three pieces of candy, which she gave to us, smiling. Shortly after, Papa and our neighbor came back.

“You should come too. Come with us to China,” he joked, patting Papa’s arm.

“No, no. We’re staying here,” Papa said. “Things will be fine. You will see.”

“Yes, well. Hopefully. Then we come back,” our neighbor laughed.

On the walk home I asked Papa what they had talked about in the room, but his eyes looked as serious as he sounded behind those doors. His grip on my hand was tighter than it was when we walked to our neighbor’s house. He was murmuring to himself and he shook his head, as if he did not hear me, and he was sweating, because of the 20sun and maybe because of what they had talked about. I asked once more but a gust of wind upstaged me. Rainy season was coming and the wind was angrier every day.

The Sound of Music was the first film in. After the first several minutes of the movie, when I realized that none of them were going to turn purple, I learned about children like me, whose mother was far away. I wondered if Mam had seen this film and if she was singing along with me. When she called that Sunday and it was my turn to speak to her, I sang her the verses that I had memorized and she laughed on the other end of the phone.

“You learned the songs already?” she asked.

I agreed and sang, and as Mam joined me her voice left the small circle near my ear and filled our den with a soft alto trembling that could only be hers. When I forgot the words of the song, Mam continued until her voice broke on the other end of the phone.

“You there?” she asked.

“Yeh, Mama,” I said, wanting all of her back in Liberia, hating the sound of music so far away.

Some Saturdays later, my Ol’ Ma was visiting from her house in Logan Town and after eating breakfast, I led her to the den to watch The Sound of Music with me. I sang along, echoing their words since I did not know them, trailing behind a story that I could not fully understand. Wi and K sat in the den also. They were more entertained by the head tie wrapped around Ma’s head than by the movie. They were taking turns unfolding it from her head and wrapping it around again.

There was a loud knocking at the front door that escalated to a persistent thud. Papa walked into the den from his room, and he looked like he was ready to yell at us for jumping or tapping on the walls.

“What’s that sound?” he asked.

The thud was accompanied by a soft wailing, voices that at first sounded like singing, then rose to collective screams. 21

We turned toward the noise and the clamor of voices when a neighbor beat on the den window.

“Turn that down,” Papa said, pointing toward the television while he opened the window.

“Mr. Moore! Mr. Moore!” The woman was Mam’s friend, and she lived several houses past our neighbors. “They coming! The war now come! They coming!” she shouted.