Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

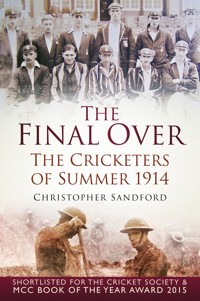

JOINT WINNER OF THE CRICKET SOCIETY and MCC BOOK OF THE YEAR 2020 AWARD The declaration of war against Germany on 3 September 1939 brought an end to the second (and as yet, final) Golden Age of English cricket. Over 200 first-class English players signed up to fight in that first year; 52 never came back. In many ways, the summer of 1939 was the end of innocence. Using unpublished letters, diaries and memoirs, Christopher Sandford recreates that last summer, looking at men like George Macaulay, who took a wicket with his first ball in Test cricket but was struck down while serving with the RAF in 1940; Maurice Turnbull, the England allrounder who fell during the Normandy landings; and Hedley Verity, who still holds cricketing records, but who died in the invasion of Sicily. Few English cricket teams began their first post-war season without holding memorial ceremonies for the men they had lost: The Final Innings pays homage not only to these men, but to the lost innocence, heroism and human endurance of the age.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 553

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

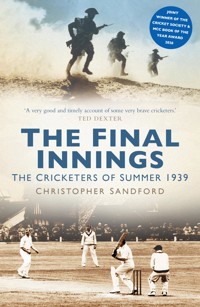

Jacket illustrations:Front: British infantry at El Alamein (Alamy) / Derbyshire v Lancashire, 1939 (Mirrorpix). Back: Spectators and cricketers lounge on the grass (public domain) / Gunners of the Surrey & Sussex Yeomanry play an impromptu game of cricket in Italy. (public domain) Author headshot: © Nicholas Sandford.

First published 2019

The History Press

97 St George’s Place

Cheltenham, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Christopher Sandford, 2019

The right of Christopher Sandford to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9276 3

Typesetting and origination by The History PressPrinted and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Also by Christopher Sandford

FICTION

Feasting with Panthers

Arcadian

We Don’t Do Dogs

PLAYS

Comrades

MUSIC BIOGRAPHIES

Mick Jagger

Eric Clapton

Kurt Cobain

David Bowie

Sting

Bruce Springsteen

Keith Richards

Paul McCartney

The Rolling Stones

FILM BIOGRAPHIES

Steve McQueen

Roman Polanski

SPORT

The Cornhill Centenary Test

Godfrey Evans

Tom Graveney

Imran Khan

John Murray

HISTORY

Houdini and Doyle

The Final Over

Macmillan and Kennedy

The Man Who Would be Sherlock

Union Jack

The Zeebrugge Raid

To Malcolm Robinson1939–2008

‘The cricket’s gone; we only hear machines.’

David McCord

‘I am all right, I have only been slightly hurt. Saluti affettuosi.’

Hedley Verity’s last recorded words before he diedfrom wounds received on the Italian front

‘Ohne Hast, aber ohne Rast’ – (‘Without haste, but without end.’)

Adolf Hitler on cricket

CONTENTS

Preface

1 Golden Age

2 Cricket Without End

3 The Bulldog Breed

4 ‘We Are the Pilgrims, Master’

5 High Summer

6 Throwing the Bat

7 The Dead Cat

8 ‘Now You Buggers Will Believe You’re in a War’

9 Endgame

Sources and Chapter Notes

Select Bibliography

Index

PREFACE

This book, published to coincide with the eightieth anniversary of the outbreak of the Second World War, is a homage to the cricketers at all levels of the game who served their country. It is not a statistical record of each and every individual combatant player of the 1939 English season. Others, notably Nigel McCrery in his book The Coming Storm, have already performed that task admirably well. Nor is it a strictly chronological trawl of each of the 290 or so first-class matches played during that ill-fated summer, for that, too, has been done, chiefly in the pages of Wisden. No slight is intended on the name of any cricketer who might be missing, and anyone interested in reading more about the subject will find some suggestions in the bibliography at the back of the book. Every effort has nonetheless been made to portray the events exactly as they occurred, and to record as accurately as possible the stories of the men and women who lived them. I only wish I could blame someone listed below for the shortcomings of the text. They are mine alone.

By our standards, the English cricketers of 1939 were ill-paid and almost ludicrously badly treated by their clubs. But with a few rare exceptions, they were a remarkably convivial and high-spirited group. It’s this same spirit that’s hopefully celebrated in this book. Rather than loitering over the scores of each match, The Final Innings attempts to follow certain players and their families, both on and off the field, during that strange summer. It seeks to shed light on the daily lives of such individuals; to demonstrate what it meant to be an ‘amateur’ or a ‘professional’ eighty years ago; and to show again the arbitrary nature of war, where one man could fall and the one next to him come home and live to be 90.

Above all, I’ve tried to portray the individuals seen here as flesh-and-blood characters, not merely as statistics, and to show them in the context of how they reacted to the partly ludicrous, partly horrific events of the period from around March to September 1939. Cricket after all is a reflection of life, and by and large cricketers answered the crisis in exactly the same way as everyone else. The records show that they volunteered at broadly the same rate as other young men, and they died, too, in equal proportion. It is a very human story.

For archive material, input or advice I should thank, institutionally: Alibris, America, The American Conservative, Bookcase, Bookfinder, Bright Lights, the British Library, the British Museum, British Newspaper Archive, Cambridge University Library, Chronicles, CricInfo, Cricket Archive, Cricket Australia, the Cricketer, the Cricket Society, Cricket West Indies, Derbyshire CCC, Essex CCC, General Register Office, Hampshire CCC, Hampshire Record Office, Hedgehog Review, Hillingdon Libraries, the Imperial War Museum, Kent CCC, King’s College Library London, Lancashire CCC, the MCC Library, Middlesex CCC, National Army Museum, National Review, Navy News, Northamptonshire CCC, the Oldie, the Peter Edwards Museum and Library, Public Record Office, Renton Public Library, Russian Life, St Martin’s Press, Seaside Library Oregon, South Africa Cricket Association, the Sunday Express, Surrey CCC, Sussex CCC, Touchstone, UK National Archives, USA Cricket Association, University of Montana, University of Puget Sound, Vital Records, Wirral Archives Service, Worcestershire CCC, Yorkshire CCC.

Professionally: Wendy Adams, Dave Allen, Leann Alspaugh, Val Baker, Phil Barnes, Sue Black, Rob Boddie, Geoff Boycott, Jennifer Boyer, Phil Britt, Michael Cairns, Dan Chernow, Sophie Cooper, Robert Curphey, Paul Darlow, Cindy Da Silva, Alan Deane, Ted Dexter, Michael Dorr, Lauren Dwyer, Mike Fargo, Jon Filby, Bill Furmedge, Jim Geller, Gethsemane Lutheran Church, Mayukh Ghosh, Tony Gill, Freddie Gray, Dominic Green, Ryan Grice, Tess Hines, The History Press, Robin B. James, David Jenkins, Neil Jenkinson, Adam Jones, Edith Keep, David Kelly, Imran Khan, Alex Legge, Barbara Levy, Cindy Link, Diana Lloyd, Barbara McLean, Christine McMorris, Robert Mann, Dave Mason, Jo Miller, Nicola Nye, Max Paley, Palgrave Macmillan, Jezz Palmer, David Pracy, Tim Reidy, Jim Repard, Tim Rice, Paul Richardson, Chris Ridler, William Roberts, David Robertson, Neil Robinson, Rebecca Romney, Jane Rosen, Malcolm Rowley, David Rymill, Sandy Cove Inn, Seattle CC, Paul Shelley, Don Short, Andrew Stuart, Charles Vann, Adele Warlow, Alan Weyer, Aaron Wolf, the late Tom Wolfe, David Wood, Andrew Yates, Tony Yeo.

Personally: Lisa Armstead, Rev. Maynard Atik, Pete Barnes, the late David Blake, Rocco Bowen, Robert and Hilary Bruce, Jon Burke, John Bush, Lincoln Callaghan, Don Carson, Common Ground, Alice Cooper, Tim Cox, Celia Culpan, the Davenport, Monty Dennison, Ted Dexter, Micky Dolenz, the Dowdall family, John and Barbara Dungee, the late Godfrey Evans, Malcolm Galfe, Garden Court Hotel, the late Gay Hussar, Jay Gilmartin, James Graham, the late Tom Graveney, Jeff and Rita Griffin, Grumbles, Steve and Jo Hackett, Masood Halim, Nigel Hancock, Hermino, Alastair Hignell, Charles Hillman, Alex Holmes, Hotel Vancouver, Jo Jacobius, Julian James, Peter Jia, Tom Johnston, Lincoln Kamell, Carol Lamb, Terry Lambert, Belinda Lawson, Eugene Lemcio, Todd Linse, the Lorimer family, Nick Lowe, Robert Dean Lurie, Les McBride, Heather and Mason McEachran, Charles McIntosh, the Macris, Lee Mattson, Jim Meyersahm, Sheila Mohn, the Morgans, Harry Mount, Colleen Murray, the late John Murray, the National Gallery, Greg Nowak, Chuck Ogmund, Phil Oppenheim, Valya Page, Peter Parfitt, Robin Parish, Jim Parks, Owen Paterson, Peter Perchard, Greg Phillips, the late Chris Pickrell, Roman Polanski, Robert and Jewell Prins, the Prins family, the late Bert Robinson, Ailsa Rushbrooke, Debbie Saks, Sam, the late Sefton Sandford, Sue Sandford, Peter Scaramanga, Seattle Prep., Pat Simmons, Dorothy Smith, Fred and Cindy Smith, Debbie Standish, the Stanley family, the late Thaddeus Stuart, Jack Surendranath, Belinda and Ian Taylor, Thomas Toughill, Hugh Turbervill, the late Ben and Mary Tyvand, Diana Villar, Ross Viner, Lisbeth Vogl, Karin and Soleil Wieland, Debbie Wild, Andy Williamson, the Willis Fleming family, Mary Wilson, Heng and Lang Woon, Doris and Felicia Zhu, the Zombies.

My deepest thanks, as always, to Karen and Nicholas Sandford.

C.S.2019

1

GOLDEN AGE

Captain Gerald de Lisle Hough arrived early at the St Lawrence Ground, Canterbury, on the Easter Monday of 10 April 1939 to begin reviving the place from its winter’s sleep. Although just 44, the Kent secretary-manager looked a full decade older. Hough was dark and short, and habitually wore a long and dilapidated tweed jacket that emphasised his lack of height. Moreover, his small frame was wracked with arthritis, and he walked with what was called a ‘corkscrewing’ gait, propelled up and down by a thick wooden cane. ‘Hough seemed to us a rather comic figure, straight out of Charles Dickens,’ the 18-year-old Godfrey Evans, then Kent’s reserve-team wicketkeeper, remembered. ‘I’m afraid some of the younger guys did impersonations of him behind his back. My attitude was, “You are an old fogey and I’m a teenager full of sap. You’ll spoil my fun if I let you, so here I go. Catch me if you can.”’

For all that, Hough was a hardworking and efficient administrator whose physical infirmity was balanced by a number of professional skills. He was a fluent writer and, despite his frailty, a commanding figure in committee meetings with his deep baritone voice and unerring grasp of detail. Although Hough himself rarely mentioned it, he was also a bona fide war hero. Commissioned in September 1914 in the Royal West Kent Regiment, he had been severely wounded a year later at Loos, a battle that was then widely regarded as the epitome of horror in its failed assault under chlorine gas on a series of German-held slag heaps. After several months’ convalescence, Hough had returned to the front in June 1916 and promptly been wounded a second time when a high-explosive shell landed close to his dugout at Vachelles in the killing fields around the river Somme. That had effectively brought an end to his war. Hough served a further two years in a reserve battalion stationed in the market town of Wendover in Buckinghamshire, where he was mentioned in dispatches for ‘exceptional wardship’, and resigned his commission only in September 1921, with the rank of captain.

Despite his injuries, Hough had also been a distinguished all-round cricketer who bowled off-spin and had a ‘thumping power and crispness about his handling of the bat that gave every stroke character and frequently left cover-point wringing his hands’. Having hit 30 and 87, both times not out, in his first representative appearance for Lionel Robinson’s XI in a match against the Australian Forces, it was sometimes suggested that Hough’s name should be included by Wisden on the list of those who have scored a century on their first-class debut, an honour the almanack ultimately denied him. Curiously, Hough also took a wicket with his first delivery in county cricket, when he bowled his former army colleague Joseph Dixon for 6 when playing for Kent against Essex at Leyton in June 1919. A teammate reported that ‘Gerry accepted the toast we drank to him that night with considerable enthusiasm.’

Twenty years later, Godfrey Evans and the other young hopefuls reporting to Canterbury had no idea that their seemingly decrepit club secretary had once been considered among the brightest all-round prospects of post-war cricket, and widely tipped to be a future England player. Instead, Hough had appeared in just a dozen more matches, privately conceding that his war wounds were proving ‘tedious’ during long days in the field, and that it would be unfair on his county colleagues for him to carry on. After scoring 11 and 0 in Kent’s crushing defeat by Lancashire in July 1920, the 26-year-old quietly slipped into retirement. He spent much of the next decade teaching at Bradfield College in Berkshire. In later life, one hot-headed Bradfield student remembered that he had been invited to bowl in the nets one day and was still ‘tearing in like the east wind even after the little chap had effortlessly carted me back over my head for about the twelfth time’.

Hough took over the secretary’s position at Kent in August 1933, in the middle of what proved to be a golden period for the county, with players like Tich Freeman, Frank Woolley and Les Ames all at or close to the peak of their powers. Nothing could make good the hard financial realities of running even a successful English cricket club in the depths of a recession, however, and like other county officials Hough was forced to cut costs where he could. By 1939 a rising young star like Godfrey Evans was paid only a basic £130 a year, ‘with third-class rail fare and a two-course meal allowance, sans drink’ thrown in for away fixtures. ‘By around early August each year the committee would be looking for names to chop from the next season’s payroll,’ he recalled.

Nonetheless, Hough was generally able to balance the books, and was remembered for one dressing-room speech that Evans paraphrased as ‘like something Churchill gave the troops during the war – “Each one of you buggers should ask himself every day what he can do, how he can contribute to the final goal” – that kind of thing.’ The Kent yearbook for 1939 reports that ‘In spite of the weather and the international situation, attendances were up by 7,000.’ In time Hough told his committee that the club’s financial situation was ‘not wholly deficient’, and that a ‘modest outlay on the regular employment of a masseur for the first time had proved a successful experiment’.

In fact, Hough was better positioned than many of his cash-strapped counterparts on cricket’s county circuit, where even A.F. Davey, the secretary of metropolitan Surrey – a club that boasted the king as its patron – wrote that a balanced budget was beyond his reach in 1939 and ‘at present only a distant dream’. Davey’s committee had come to this conclusion long before he did. ‘Without corrective action there is a looming risk of several first-class venues facing financial difficulties and even insolvency,’ The Times wrote, in words that were to be echoed at regular intervals during the later twentieth century, when reviewing the English county scene as a whole.

At least in 1939 there was no conflict between the traditionalists who remain wedded to the three- or four-day championship format and those who crave an expanded Twenty20 competition and other cash-generating innovations, simply because the concept of limited-overs cricket barely existed eighty years ago. Even a tentative proposal that Rowland Ryder, the longstanding secretary of Warwickshire, put forward for two-day county matches to be played on a Saturday and a Monday came back with a one-word comment stamped across the paper: ‘Rejected’.

It’s worth dwelling a moment longer on English county cricket’s straitened finances in 1939, if only to dispel the myth that a golden age still characterised by dashing, moustachioed amateurs and suitably deferential yeoman professionals, performing in front of packed, shirt-sleeved crowds debating between overs such hot issues as the lob-bowling controversy of the 1770s, or whether Lumpy Stevens would have been a match for Sydney Barnes, was necessarily one that might have been expected to survive after the war. Reviewing the 1939 season in Wisden, R.C. ‘Crusoe’ Robertson-Glasgow wrote: ‘Three-day cricket, in peace, was scarcely maintaining the public interest except in matches between the few best, or the locally rivalrous teams, and how many will [now] pay even sixpence to watch cricket for three days between scratch or constantly varying elevens?’ An anonymous correspondent wrote to the Cricketer with a damning comparison that December. ‘The MCC will bring out its finest fizz to drink in the acclaim of another brilliant year at Lord’s. To many others tending to the health of an English cricket club today it will be a case of counting every penny and praying for a possible resumption following the hostilities.’1

Of Derbyshire’s season, Wisden reported: ‘The wet summer hit the county hard financially. A testimonial fund for Worthington amounted to £720’, or roughly £19,000 in today’s money, to reward an England Test star then in his sixteenth consecutive year of service with the county. For their part, Gloucestershire enjoyed one of their more successful campaigns in 1939. ‘Always ready to offer or accept a sporting challenge in the hope of providing an interesting finish, they set the fashion in the enterprising cricket which prevailed over most of the country,’ it was reported. Yet when the officials at Bristol added up the final figures in September, they too were forced to admit: ‘Considering the team’s achievements, our matches were not well patronised.’ It was the same story at Lancashire, ‘where rain seemed to follow the team, causing 13 blank days’, and tributes in the annual report to the ‘grand work of our batsmen’ were drowned out by statistics of spiralling costs, falling revenues and only ‘fitfully successful’ investments.

Gates were also a concern at Sussex, where the 36-year-old all-rounder Jim Parks, then in his thirteenth and final season at the club, ‘failed to recapture his [past] glories, and this, besides the imminence of war, may have accounted for his benefit bringing him no more than £734-10-6, including collections and subscriptions.’ Further on in the same report of the county’s 1939 fortunes, a sad note concludes: ‘The weather and the international situation, causing the match with the West Indies team to be cancelled, accounted for a loss on the year of £1,853.’ ‘It wasn’t just me winding his career down,’ Parks later reflected. ‘Some of us thought the club’s number was up, too.’

Even at county champions Yorkshire, Wisden wrote: ‘After making the usual allowances and bonuses, the committee reported a profit on the season of £54’ – about the amount the club would have needed to buy each one of its sixteen professional players a basic off-the-peg suit, had it wished to do so, with just enough left over for a modest team dinner.

Perhaps the one exception to the financial woes afflicting England’s county cricket circuit came at Middlesex, a club in the enviable position of playing their home matches at a venue then unchallenged as the sport’s global headquarters. Lord’s was not immune from the effects of the build-up to war in 1939, with a barrage balloon already casting its dark shadow over the Mound Stand when play got underway in the championship match against Somerset on 23 August, the Long Room stripped of its treasures, and sandbags packed up at the gates. But it is the little rituals that most accurately represent the old spirit of the ground and its uniquely prosperous county tenant. The Lord’s authorities were particularly concerned early that season not with civil defence, but with ‘a project for replacing the present Bakery with one located in the disused Racket Court … This move will involve the loss of one Squash Court, but will increase the efficiency of the Refreshment Department.’

Reading the catalogue of gifts made to the Marylebone club at the time much of Europe was mobilising for war that summer is to evoke thoughts of P.G. Wodehouse. The list begins with a vote of thanks ‘to Earl Grey for the photograph of a sculptured arm holding a ball dating from the time of the Ptolemies’. Gratitude was also expressed to ‘Mr R.K. Mugliston for a belt buckle’, and ‘Sir Colin MacRae for a picture of I Zingari v The Army taken shortly after the relief of Bloemfontein in the South African War.’ There were many ‘heads and horns’ of dead animals donated by the club’s hunting element – possibly a majority of the 6,996 (then all-male) members, each paying around £15 a year in order to sit in the Lord’s pavilion, wear the distinctive scarlet and gold colours, and enjoy other perks. On match days, meanwhile, the amateurs’ dressing-room attendant continued to lay out the players’ neatly pressed flannels at the start of play; continued to arrange symmetrically the freshly ironed morning newspapers on the polished side table, and to supply a steady succession of cups of tea and other refreshments served on a crested silver tray. The professional players were not so fortunate, and the 21-year-old Denis Compton later described his core working environment in 1939 as characterised by the ‘pong of old socks and stale fag smoke’.

In the same week that Gerald Hough was airing out the musty back rooms in the Canterbury pavilion and writing elegiacally in his diary of ‘a day of awakening blue, all varnish and high hopes’, the Home Office sent out letters of instruction to 65,000 official ‘enumerators’ who would descend upon every household in England and Wales later in the summer to carry out what became the most comprehensive survey (as opposed to formal census) ever taken of the population. The data gathered offers an intriguing snapshot of a generally contented nation set in the context of the deteriorating European order of the late 1930s. To take the figure which made the greatest impression on contemporary public opinion: between January 1933 and January 1937, the total number of unemployed British males fell from 22.8 to 13.2 per cent of the available workforce, and by the beginning of 1939 the figure was 8.1 per cent. By Christmas of that year, with the nation now at war, what had been among the worst unemployment figures in Europe had been turned into a labour shortage.

The statistics also illustrate how Britons’ working lives have changed since 1939 – especially for women, 9.3 million of whom were then described as carrying out ‘unpaid domestic duties’, with 588,000 more working as live-in or full-time household servants. It was also a relatively young society: the figures show that the average age for men was 33 and for women 34, compared to 39 and 40 in 2019. Out of the 41 million people surveyed, just 111 were aged 100 or more, less than 1 per cent of the total of 13,000 British centurions today.

Despite the apparent drudgery of many men’s and more particularly women’s lives, the historian Martin Pugh describes it as a ‘feminine’ era, with some modest innovations in areas like hemlines and hairstyles, and a wealth of popular magazines such as Good Housekeeping focusing on the virtues of home and hearth. The data reveals that 46.2 per cent of the population was married, and that 6.5 per cent had been widowed, but that just 0.1 per cent was divorced. Today 37 per cent of the total population is married, and the divorce rate hovers at around 45 per cent. In 1939 roughly one in twenty of British children was born out of wedlock, a tenth of the modern figure.

‘Business as usual’ was the motto reintroduced by many British retailers during the summer of 1939, echoing the slogan adopted under conditions of similar international disquiet twenty-five years earlier. The self-confidence of the phrase concealed a wide variety of individual household fortunes, with the ‘finest fizz’ available at some tables and a diet rich in commodities like bully beef, boiled potatoes and rice pudding, frequently with a cigarette chaser, at others. George Orwell described the age as one centred around ‘tinned food, the Picture Post and the combustion engine’. The arts scene was similarly diverse: 1939 found Barbara Cartland already in full sail with her eighteenth novel, The Bitter Winds of Love, but it also saw the publication of James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. Roughly 20,000 British households had a television set before their manufacture ceased during the war. The international film industry was booming, with Wuthering Heights; The Four Feathers; Goodbye, Mr. Chips; The Wizard of Oz and Gone With the Wind among the new releases. It was also something of a golden age for music, high and low. Arnold Bax, Benjamin Britten and William Walton all debuted new concertos, while the song most frequently heard on Britain’s 9 million household radio sets was the Leeds-born Michael Carr’s ‘South of the Border (Down Mexico Way)’.

In November 1939, a 38-year-old Iowa farmboy-turned-advertising executive named George Gallup and his young female assistant sailed for Britain, where over the next six weeks they enlisted a small team of regional helpers to knock on a total of 6,200 doors in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Glasgow and, rather curiously, the area around Mamble in Worcestershire, in order to ask residents about their attitudes to everything from the war to the advent of tinned tomato juice on British breakfast tables. One of Gallup’s conclusions when publishing his poll in June 1940 was that ‘the forces of conformity … after the great rise in the unorthodox spiritual movement in the 1920s … coupled with the natural anxieties of the German war, [had] led to a religious revival that appears to be both intense and pervasive.’ Just over 65 per cent of adult Britons canvassed agreed that they drew ‘significant comfort’ from regular church attendance. Paradoxically, only 48 per cent of respondents admitted to believing in life after death, although this figure would rise as the nation’s war losses mounted. Britons, Gallup wrote, were prone ‘to a certain fatalism even in happier times’ and ‘often abide the ills of life more stoically than [their] American cousins’. His poll also confirmed that the ‘physical, social and political milieu in the United Kingdom remains sharply status-conscious’, and perhaps even more than the statistics it’s reading some of the newspaper headlines of the day (‘Butler Driven Mad by Jealousy’; ‘Lady Lansdowne and Staff will Take a Shooting Lodge for August’; ‘City of London Regiment Seeks Men: Upper- and Middle-Class Only Need Apply’) that tells the tale.

Cricket itself was still conducted ‘in a reverent atmosphere, much akin to a church’, wrote the drama critic and composer Herbert Farjeon, author of the immortal song ‘I’ve danced with a man, who’s danced with a girl, who’s danced with the Prince of Wales’. ‘The chief difference is that most of those in attendance at Lord’s would not seem to be faking it.’ Alfred Hitchcock caught some of the intrinsic spirit of the game in his 1939 film The Lady Vanishes, which sees two impeccably upper-crust cricket buffs navigating their way home through the jackbooted officials and villainous spies of the Balkan nation of ‘Bandrika’ in order to watch the final overs of the Test at Old Trafford. It might not be a stretch to say that the director intended the characters to be symbolic of a peculiarly British obstinacy in the face of Nazi aggression. In any event the New York Times reviewer wrote appreciatively of the ‘bumbling aristocratic image of the English national sport’ depicted in the film. ‘Its devotees may be stolid and even a bit slow-witted in their Edwardian languor, but they are also the sort of calm, phlegmatic types who will battle to their last breath to preserve the British way of life.’

The testimony of almost all those who played first-class cricket in 1939 revealingly hints at the impassable gulf that existed between the classes, both on and off the field. ‘It was a feudal system,’ Godfrey Evans recalled, adding that throughout his twenty-year career he had never quite shaken the feeling that he was playing the part of some ‘useful servant’ in a rich man’s house. With the exception of some of the more progressive-minded county sides, the captain still led his fellow amateurs on to the field of play through a separate gate than that used by the horny-handed professionals, a distinction that extended to matters involving meals, hotels and transportation. Lionel Tennyson, Hampshire’s superbly ancien régime leader for much of the interwar years – and still playing representative cricket as late as 1944 – remained fond to the very end of his tenure of communicating with his batsmen in the middle by way of a telegram. If something about the current scoring rate displeased him, for instance, Tennyson’s practice was to summon a messenger boy to the captain’s dressing room and dictate a wire that might read: ‘Too slow. Run self out’, or, alternatively: ‘No more boundaries. Restrain urge at once.’ The messenger would then take the slip to the nearest post office, where it would be transcribed into a cable and in turn brought back to the ground to be ceremonially presented in between overs to the offending player.

Of course, the Lionel Tennyson school was by no means the whole story. It’s true that the underlying British class structure would come under steadily increasing pressure from within and without in the years either side of the Second World War, but it’s also true that the basic master-servant composition of most first-class cricket teams survived up until the abolition of ‘player’ and ‘gentleman’ status in 1963, and thus long enough to see the advent of the Rolling Stones, the hydrogen bomb and the space age. Even today it’s still mildly odd to read press reports about Len Hutton’s batting or Godfrey Evans’s wicketkeeping in 1939 set amongst all the advertisements for butlers, maids or chauffeurs (‘Rolls Certificate and discreet service essential’), or the lingering accounts in Wisden of innumerable matches such as Beaumont v Oratory, somewhat below the first-class, or to note that the almanack devoted 105 closely typed pages specifically to public-school cricket that year, which is roughly ninety-eight more than it does today.

These were far from the only points of distinction between the English summer sport as it appeared in 1939 and as it does now. Things were generally more haphazard back then when it came to playing conditions and facilities, with a touch of the ramshackle about even the great Test match grounds. Not yet troubled by health and safety requirements, these were often little more than mown fields circled by a few rudimentary stands, some covered, some not, whose architects seemed to have had a poor idea of comfort. Neville Cardus remembered that when watching England play the West Indies at Lord’s, ‘the boundary was no more than the toes of those spectators lying on the grass’. Denis Compton added that at one point the professionals’ dressing room at cricket’s headquarters had been not so much in need of repair as in ‘imminent danger of collapse’, with ‘splintered floors and a couple of rusty tin baths’. These were conditions of Babylonian luxury compared to those at lesser grounds. A Kent-based reporter named Hugh Sidey remarked of the old press box at Canterbury, far removed from today’s media centre: ‘You’d look up from scribbling something in your notebook and find some inky-faced kid in the crowd staring at you through the broken glass in the window, probably wondering if it was your story that had made him choke on his cornflakes the other morning.’

When Kent played on their out-ground at Maidstone, Godfrey Evans remembered, the side’s main concern was to ‘not vanish down one of the gaping potholes on the wicket’. The non-playing amenities were equally basic, with a pervasive smell of boiled cabbage and other, more noxious odours that ‘wafted over from the direction of the khazis’. On the occasions when Northamptonshire staged first-class fixtures at the Town Ground in Rushden, with its notoriously jerry-built pavilion, the visiting side generally found it best to first put on their whites at their hotel or, failing that, to struggle into them behind a nearby tree. When in July 1939 Somerset hosted Essex at the Rowdens Road Ground in Wells, the teams performed on what was essentially a roped-off corner of a large dog-walking park. It had few pretensions to elegance. Wisden wrote that the first first-class match to be played at the venue, when Worcestershire beat Somerset by an innings and 105 runs in July 1935, went ahead in ‘novel conditions’. It added: ‘There were no sight-screens, and the match details were broadcast from the scorers’ box by means of a microphone and loudspeakers.’

Born in September 1914, the MCC, Free Foresters and sometime Hampshire batsman John Manners was able to tell an interviewer more than a century later, ‘The uncovered wickets were often unplayable’ in the 1930s, before adding that what might now be considered sharp practice barely raised an eyebrow then. ‘At Hampshire we had a medium-pacer called Creese. The first thing he did when he came on to bowl was bend down and rub the ball in the dirt.’ Manners, currently the oldest living first-class cricketer, went on to confirm a widely held view of pre-war cricket when he admitted, ‘Some of us were pretty sluggish in the field back then. Even the younger ones stopped the ball with their foot sometimes. You don’t see that now.’ A variation on this theme was provided by the 49-year-old Lionel Tennyson when, standing in the outfield at Lord’s on the first morning of an MCC match in July 1939, he languidly trapped a windswept newspaper under his boot, picked it up and read it. He said later that the racing page was ‘altogether more engrossing’ than the cricket.

For all that, a certain amount of change was afoot in English cricket during that last pre-war season. For one thing, there were more professional players about on the county circuit generally. The ratio varied widely from side to side, but broadly speaking the further north you went, the greater the preponderance of cricketers who were paid for their services. At Essex they had twelve professionals and ten amateurs on the books in May 1939, while in Yorkshire the split was sixteen to four. At the equivalent stage in 1914 the figures had been, respectively, nine to fifteen and fourteen to seven. In recent years several former public-school players, like Gloucestershire’s Charles Barnett, had felt able to turn professional, while the incomparable Wally Hammond had explored the boundaries of the English social divide by enjoying a grammar school education before going on to be paid to play cricket for seventeen seasons, and ultimately to refine his status within the prevailing class structure by declaring himself an amateur at the age of 35, largely in order to satisfy the established MCC concept of the gentleman Test captain.

Among the game’s more technical innovations, 1939 was the one and only season in which English cricket adopted the 8-ball over. The home Tests were each of three days’ duration (Saturday, Monday and Tuesday), and the fielding side could request a new ball after every 200 runs scored. On 28 March of that year, the Advisory Committee of the MCC met at Lord’s to discuss the age-old problem of the proper balance between bat and ball. It concluded: ‘All counties must instruct their groundsmen that the ideal wicket is one which makes the conditions equal as between batsmen and bowlers without being dangerous … Under no circumstances should pitches be prepared so as to favour the bat unduly.’ Perhaps as a result, scores were generally lower in 1939 than in 1938. Only six English players managed an aggregate of 2,000 first-class runs compared to 11 the previous season, with even Hammond falling from 3,011 runs at an average of 75.27 to the relatively paltry total of 2,479 runs at 63.56. Of the leading bowlers, Hedley Verity took 158 first-class wickets in 1938, Tom Goddard took 114 and Doug Wright took 110. In 1939 the figures were 191, 200 and 141 respectively.

It was thought that there was little official need to dwell on any particular concerns about unsportsmanlike conduct in 1939, although the MCC politely reminded umpires that they ‘should not allow themselves to be unduly influenced by appeals from such of the field who were not in a position to form a judgement on the point appealed upon’, or by ‘tricks – such as throwing up the ball, on appealing for a catch at the wicket, without waiting for the decision, etc.’ Due to unspecified ‘ricochet incidents’ in the 1938 season, the MCC now also added the curious edict: ‘The umpire is not a boundary.’

Technology, too, was marching on. National radio broadcasting – in part made possible by the work of the brilliant but underfunded British physicist and disciple of the paranormal, Sir Oliver Lodge – had begun in June 1920 when the 59-year-old Australian soprano Dame Nellie Melba introduced a concert of recorded opera music, which she fitfully accompanied in a karaoke-like effect, followed by a poetry recital and the national anthem, beamed out from a disused army hut at Writtle in Essex. The newly launched BBC issued a total of 206,000 household radio licences, at 10s each, in 1923. By 1930 the figure had jumped to 3 million licences and stood at close to 10 million on the outbreak of war in 1939. The demand for radio sets rose even in the Depression years, when there was a dip in the sale of almost every other popular commodity. ‘Never a passenger on the austerity bandwagon, the wireless has become a friendly voice in nearly every British sitting room,’ wrote Lodge, who had become convinced that the radio also permitted the spirit world to communicate with the living one over the ether.

John Reith, the morally austere director general of the BBC from 1927 to 1938, seems not to have shared Lodge’s faith in the occult potential of the new medium, but wrote not long before his departure from the corporation: ‘There are clear benefits to a service offer[ing] education and uplifting entertainment, and in so doing acting as an inspiration to and encourager of healthful recreation’ – the slightly bombastic mandate that had been translated during the late 1920s and early 1930s into the first live broadcasts to be made of English cricket.

Reith’s principal instrument in carrying his vision out was an Eton- and Cambridge-educated brigadier general’s son named Seymour Joly de Lotbiniere. Born in 1905, ‘Lobby’ had joined the BBC after a brief and unhappy stint in the law and rose to become director of outside broadcasting from 1935 to 1940. His preferred commentator in those early days of ‘trial and no little error’, as he put it, was a former club cricketer and Oxford rugby blue named Howard Marshall. Marshall’s descriptive powers were perfect both for the game and its frequent interruptions. Instead of talking exclusively about the cricket, the Athletic News wrote, his commentary typically ‘dwelled upon matters such as the number of passing birds, and the variety of interesting hats to be seen in the ladies’ stand’, clearly a harbinger of much of today’s radio coverage. The poet Edmund Blunden wrote appreciatively: ‘On the air, Mr Howard Marshall makes every ball bowled, every shifting of a fieldsman so fertile with meaning that any wireless set may make a subtle cricket student of anybody.’

In October 1938, the BBC commissioned a 31-year-old rugby and cricket writer named Ernest William Swanton to commentate on that winter’s MCC tour of South Africa. Even in his early incarnation, Swanton was a somewhat imperious figure, whose deep, fruity voice and commanding style earned him the nickname ‘Jim’ as a humorous reference to ‘Gentleman Jim, the Journalist’. He was not, it has to be said, an especially imaginative recorder of play in the style of Marshall, and he had no striking turn of phrase. But he was a sound, professional broadcaster nonetheless, who spoke lucidly and always with superb authority.

Swanton’s winter engagement in South Africa represented only the most meagre financial outlay by the BBC. Arriving in Cape Town on 6 December 1938 and leaving again on 17 March 1939, he was paid £122 (roughly £3,200 today) for his services, a rate of about £1-4s per day, or just over £5 for each of the twenty-one first-class matches he covered. When the fifth and ‘timeless’ final Test at Durban developed into a ten-day marathon, and the Englishmen had to hurriedly revise their homeward travel plans as a result, the BBC sent Swanton a cable proposing that they pay him an extra £15 for his trouble. He accepted the offer.

As a result of all this, the first day of the Test at Johannesburg, which fell on Christmas Eve 1938, proved to be the first occasion when a live cricket broadcast was sent back to the UK. It was an inauspicious start. ‘The commentary box held only one (no scorer),’ Swanton recalled. ‘I had not had time to get acclimatised to the 6,000-ft altitude, while on the field the action was minimal.’

As a whole, the match-day facilities both at home and abroad were not ones the modern commentator would envy. When broadcasting at the Oval, Swanton, generously padded even then, ‘swayed up a narrow ladder into a rickety wooden cabin perched over the general direction of long-leg, from which half a dozen fielders, a batsman and an umpire were generally in view’. Howard Marshall added: ‘Even attaining one’s seat in those days required a stamina and agility normally associated with a Royal Marines obstacle course.’

Nonetheless, Swanton was on hand to join Marshall and their BBC colleague Michael Standing in the broadcasting box for the 1939 home Tests against the West Indies, the first to be covered ball by ball throughout the day, and which were also transmitted back to the Caribbean. There was some trepidation at the idea of providing six hours of uninterrupted live commentary for an audience of around 200,000 home listeners, let alone their fanatical overseas counterparts. Swanton believed the initiative was the result of a rash promise ‘made by a Governor of the BBC on a winter cruise of the West Indies … When he came back to Broadcasting House there was some consternation at what he had let us in for.’ The red-letter day duly came on 24 June 1939, when Swanton cleared his throat and announced drily that Bill Bowes would now come in to bowl the first ball of the first session of the match at Lord’s, ‘in the teeth of a brisk nor’easter’, to the West Indies opener Rolph Grant. It was the gentle precursor to what became known eighteen years later as Test Match Special.

BBC Television had meanwhile provided occasional, rudimentary coverage of the Lord’s and Oval Tests against Australia the previous summer, but only now matched the ambitions of its sound colleagues. The Times of 24 June lists: ‘11.30 a.m. cricket: Televised direct from Lord’s, featuring commentary by Thomas Woodroffe’, with a teatime segment billed as ‘Percy Ponsonby Goes to the Test’, followed by more ‘televisual pictures until the close’, which gave way to the news and an Edgar Wallace play called Smoky Cell before the airwaves shut down at 10.30 p.m.

Back in Canterbury, Gerald Hough, born in 1894, wrote a note to his committee wondering if they should invest the necessary 40 or 45 guineas in a new EKCO ‘televisor set’ for the members’ lounge, but was worried about the possible effect this might have on ‘one viewing the cricket at first hand, as opposed to through an inanimate box’. Hough was particularly concerned by the current BBC slogan, You Can’t Take Your Eyes From It. ‘Will we all someday soon be experiencing life this way, not conversing with one another, and never averting our gaze from the screen?’ he asked, presciently.

____________

1 The unnamed writer had a point: the MCC’s auditors reported that same month that 100,933 spectators had each paid around 2s at the turnstiles over the four days of the England v Australia Lord’s Test in 1938, and that after all expenses were met the club had made a net profit of £41,823-1s-1d (roughly £1.3 million today) during the year as a whole.

2

CRICKET WITHOUT END

The fifteen players and three officials of the MCC touring party who assembled to catch their boat-train from London’s Waterloo station on 21 October 1938, and who disembarked two weeks later at Cape Town, did so amid some little tension both in terms of cricket and the wider world. The side was led by Gloucestershire’s Walter Hammond, a peerless batsman who was not so well cast for the man-management aspects of the job. ‘Wally took on the captaincy with professional dedication,’ his tour colleague Paul Gibb remembered. ‘But he believed in letting you get on with it rather than offering you the benefit of his support or wisdom. We hardly saw him once stumps were drawn. I think “reticent” would be the word now, but at the time we thought him a gloomy sort of bugger.’

Hammond’s biographer David Foot has suggested that he was suffering from what is known euphemistically as a ‘social disease’ contracted in the West Indies in 1925–26, and that this accounted for his mood swings later in life. There were strains, too, in Hammond’s marriage to his long-suffering wife Dorothy, who saw photographs in the English press of her husband beaming down at a local beauty queen named Sybil Ness-Harvey at an official reception in Durban. ‘But Dot, you know what it’s like at these affairs,’ Hammond protested in a letter home. ‘I’m the captain now and have to mix.’ Perhaps it was to further assuage her anxieties that he wrote: ‘She’s just another girl with a double-barrelled name out here.’ But Mrs Hammond remained unmollified. Eight years later, having divorced Dorothy, Hammond married Sybil in a brief ceremony at Kingston Register Office, an event none of his Test or county cricket colleagues attended.

The lifestyles of one or two of the players who toured South Africa under Hammond’s leadership perhaps also defied the MCC orthodoxy of the day. In particular, there was 22-year-old Bill Edrich of Middlesex, who was selected despite having scored only 67 runs at an average of 11 in four home Tests against Australia the previous summer. Apart from his form with the bat, Edrich also posed something of a challenge to the social decorum of the side. His drinking exploits were legendary, and he was judged even by Lionel Tennyson to have ‘overdone the Bacchic rites’ while playing in a side Tennyson led to India in the winter of 1937–38. Edrich was small and busy, with an upturned nose that gave him a vaguely feral air – ‘like a randy mole’ in one woman’s later assessment. In time his England career would be rudely interrupted when he came back to the team hotel in the early hours of the morning of a Test match at Old Trafford and had to be helped to bed by the night porter, in the process waking the occupant of the next room, who happened to be the chairman of selectors.

Elsewhere in the South African tour party, there was 38-year-old Tom Goddard, a fine off-spinner for Gloucestershire in his day, who came almost to hate his county and Test captain. ‘Don’t like the way Wally behaves when his wife is away,’ he remarked. The feud came to a head in 1947, when Hammond refused to play in Goddard’s benefit match. Doug Wright of Kent had also had a modest time while bowling his leg-breaks against the 1938 Australians and had trouble with no balls due to his odd run-up. ‘He waves his arms widely, and rocks on his legs like a small ship pitching and bobbing in a heavy sea,’ one critic said of him. Standing 6ft 6in, the swarthily handsome Ken Farnes of Essex was another bowler who had been only fitfully successful the previous summer, and one who, despite having a ‘glad animal action’ and ‘liking to thud the ball into the batsman’s ribs’, was widely suspected of being an intellectual. When sailing into Port Said on a previous MCC tour, Farnes wrote in his diary: ‘We passed no other ship save the ship of the desert trotting through the sand. The sun fell. And the deep sunset red of the desert filled the western sky. Stars, with strange suddenness, bedewed the night.’ Later he wrote: ‘The sun came out and silvered the reef’, but crossed out ‘silvered’ and inserted ‘jewelled’, evidently feeling that was the mot juste.

Hammond’s tour also went ahead at a time of rising tension on the world stage. On 8 November 1938, the day on which MCC began their first match in South Africa, the British Home Secretary Samuel Hoare told the cabinet in Downing Street that his department was preparing an Air Raid Precautions Bill, and that ministers would need to discuss further the ‘provision of blast-proof shelters in existing buildings’. That same week, Germany exploded in an orgy of state-sanctioned violence against its Jewish minority in the notorious pogrom of 9–10 November 1938, known, because of the shards of glass littering the pavements of Berlin and elsewhere, as Kristallnacht. Speaking two months later to an audience of army commanders in the Kroll opera house, Adolf Hitler restated his belief that Germany’s future could only be secured by the appropriation of ‘living space’. ‘Be convinced, gentlemen,’ he added, ‘that when I think it possible, I will take action at once and never draw back from the most extreme measures.’ In between playing cricket in Johannesburg in February 1939, Ken Farnes wrote in a letter back to a friend in Essex: ‘A Napoleonic character, Herr Hitler’ and asked: ‘What will happen now?’

The eleventh MCC tour of South Africa nonetheless provided both agreeable cricket and a welcome relief from outside events, at least up until the moment of the fifth Test at Durban, which was to be played to a finish, whatever it took, if neither side then held more than a one-nil advantage in the series. This unique endurance test aside, Wisden judged it a ‘highly successful visit by practically the full flower of England’s cricketers, which gave a great fillip to the game in South Africa’. Three of the first four Tests were drawn, and England won the other one. Hammond scored 1,025 runs on the tour at an average of 60, and eight other batsmen besides him hit centuries. Four of the five major MCC wicket-takers were spinners. In the third Test at Durban, which England won, Eddie Paynter of Lancashire hit 243 in just over five hours. Wisden said: ‘The game attracted big crowds, 12,000 people, who paid £1,200 – a ground record – watching play on the second day.’

The tourists moved around the southern continent by air-cooled train, with first-class seats for the amateurs, and travelled in some style as a whole, though Swanton later wrote in a serious libel: ‘Many of the overnight accommodations were strictly of the Blackpool guesthouse variety.’ The same commentator noted of South Africa in general:

One encountered the black only in friends’ houses where the servants, in retrospect, with their simplicity, humour and natural good manners seem[ed] not too unlike the West Indians one came later to know; in domestic surroundings, and at wayside stations where cheerful urchins offered delicious peaches for sale at the train windows as one relaxed in one’s coupe.

The discrepancy in touring conditions as between then and now sometimes extended to the field of play. At Bulawayo in early February there was no ‘grass of a uniform texture’ in the middle, as promised, nor grass of any sort. The batsmen took guard on a threadbare matting wicket, and the outfield consisted of white sand sprinkled liberally over a crust of mud. A few days later, in Salisbury, the groundsman dried the pitch by the expedient of setting it on fire. In the innings victory over Orange Free State achieved on a ‘malign trampoline’ of a wicket in Bloemfontein, Norman Yardley of Yorkshire scored 182 and his county colleague Hedley Verity took 7-75 in the second innings, despite being hit for 42 runs in 3 overs by the Free State’s number eleven, a local electrician appropriately named Sparks. A team of oxen laboriously dragged the heavy roller across the pitch at East London.

Socially, one could take the view that some of the Englishmen used the tour as an opportunity to boldly explore the limits of their wedding vows, and that this constituted a sorry lapse of personal morality as defined in the 1930s; or, conversely, that their behaviour was only the sort of thing that was bound to happen from time to time when red-blooded sportsmen are sent away from home for five months. As so often, Bill Edrich was the trailblazer in this particular area. Even under the captaincy of Lionel Tennyson, himself a noted swinger, Edrich had been discreetly warned to ‘in future be more restrained in your cups’. It was good advice, but it apparently didn’t work. Already married to the first of his five wives, Edrich appeared at the team hotel in Pretoria accompanied by a pneumatic young woman he introduced as ‘Roxy – a masseuse’ and whom the Rand Daily Mail described as the player’s ‘bosom friend’ when she joined him at a civic function in the town. Swanton believed that this was ‘not an entirely isolated fall from grace’ on the Middlesex player’s part. Earlier in the tour, Edrich had actually subjected himself to a strict routine of early nights and ‘severely rationed drink and smoking’ in a bid to recover his form with the bat, but found that this regimen only ‘made me more nervous than before for the big occasion’.

By the time Edrich arrived at Durban for the climactic fifth Test he was emphatically off the wagon and only too happy to accept the pre-match hospitality of Harold ‘Tuppy’ Owen-Smith, the former Middlesex and South Africa all-rounder who lived in the city. ‘They had to put Bill to bed early that morning,’ Edrich’s brother Eric later confided. ‘He was still smiling when they shook him awake to go out to play in front of a full house.’ Edrich managed only 1 run in the England first innings, but followed this with a knock of 219, made in seven and a quarter hours, in the second. During the afternoon interval, Flt Lt Albert Holmes, the moustachioed MCC manager, poured the not-out double centurion a glass of champagne with the words, ‘I hear you train on the stuff.’ Edrich downed a second glass as well but was then out in the first over after tea – if it could be called that – having both seen England to 447-3 and probably saved his own Test career in the process.

The moral latitude Edrich allowed himself in South Africa was matched by that of his captain Hammond, whose thick dark thatch of hair and twinkling eye was said to have been especially enticing to the tour’s female spectators. Swanton recalled: ‘Hugh Bartlett of Sussex was a magnificent player and very attractive chap. But at Bloemfontein he made the cardinal error of showing a good deal of interest in the girl Wally had his eyes on. An unwise thing to do.’ Despite making a century in that particular match, Bartlett duly found himself out of favour when the England team was announced for the first Test soon afterwards. ‘The first I knew of it was when I looked at the list pinned to the dressing room door and saw Bryan Valentine’s name there instead of mine.’

Other players preferred a more elevated approach to their off-duty hours during the tour. Hedley Verity was said to have walked around each town on the team’s itinerary dressed in a ‘neat blue suit [and] what looked like a pair of dancing shoes’, making many new friends wherever he went. The tall, sharp-eyed bowler, whom Swanton thought resembled an intelligent bird, received several offers of coaching appointments in the event he and his young family might wish to settle in South Africa. Verity’s 22-year-old Yorkshire teammate Len Hutton had left his fiancée Dorothy behind in Pudsey but contented himself with a regimen of long-distance runs and early nights with a good book to solace the void. ‘Anyone got a fag?’ was the nearest Hutton ever came to a note of self-indulgence, a query quite often followed by ‘Then I’ll smoke one of my own.’ For his part, Ken Farnes privately recorded five personal objectives for his time of South Africa, none of them specifically related to his bowling, but which included:

To remain conscious of my inner, natural, more realised self instead of being overcome by successive and accumulated environments experienced on tour.

Elsewhere in his diary, Farnes admitted to feeling ‘removed’, ‘dissociated’ and ‘disgruntled with myself’, and aspiring to a ‘subjugation of self’ that would enable him to achieve ‘the required metaphysical state’. His shining moment came early on in the tour when he took 7-38 to destroy the Western Province batting in the state match at Cape Town. ‘Neither the South Africans nor I could quite believe it,’ Farnes wrote.

The events that followed the England team’s arrival for the limitless Test at Durban beginning on Friday 3 March 1939 can be quickly summarised: The South African first innings of 530, made in supremely relaxed style, the first boundary coming only after nearly four hours of play; the crowds, big at first, growing smaller; the subsequently diminished atmosphere, over which Farnes admitted, ‘I should prefer to draw a veil … There was so much batting it would be tedious to mention details’; Verity’s 766 deliveries in the Test; the final ‘impossible’ target of 696 to win; Edrich’s hungover heroics; at lunch on the tenth day the tourists needing another 118 with 7 wickets in hand; the cussedness of heavy rain then falling just as the match seemed finally to be staggering to a close; the Englishmen declining the offer of a plane and instead hurrying for the night train to Cape Town in order to catch the mail steamer Athlone Castle home; Farnes’s private remark that ‘Even the Good Lord stopped on the seventh day and rested’, and Hammond’s public one that that ‘I don’t think timeless Tests are in the best interests of the game, and I sincerely hope that the last one has been played.’ To date he has got his wish.2

The Athlone Castle herself, tricked out in purple livery in honour of the returning cricketers, her public rooms teeming with prospective brides of one sort of another, ‘wasn’t the worst place in the world to spend a damp fortnight in early spring’, Swanton reflected. ‘Bill Edrich was a lively young fellow at the time, and I daresay he added to his winter’s score, as it were.’ Early on in the voyage, Edrich decided to throw himself a 23rd birthday party, even though this was still at least a week early. He would remember forty years later:

There was a raging storm outside, I seem to recall, and the heating broke down in the ship’s restaurant, but that didn’t bother me at all. I drank toasts with the manager and toasts with the players, and somehow I managed to notice that the skipper had for company a well-upholstered young American lady who was wearing a low-cut frock and a diamond tiara and telling him how much she wanted him to bowl a maiden over. I think we’d earned our night out, because it wasn’t as if any of us got rich from the tour. When everything was added up I put about 200 quid in the bank for my five months’ work, so no wonder everyone enjoyed a bash when they could get one.

Edrich continued:

I had a great time. At least everyone told me I did. Somebody stuck a Red Indian headdress on my bonce and when I woke up that’s all I was wearing. Luckily we were crossing the Equator later that day and we greeted it in fancy dress. Wally Hammond had a long black coat and a fat cigar in his mouth and he looked like a cross between a riverboat gambler and an undertaker. There were more toasts – toasts to King and Country, and the Empire, and the MCC, and then Kenny Farnes stood up and made one to world peace, and after that there was a bit of a lull in the room. He’d said something we all had on our minds.

Edrich always perked up at the prospect of a party, or for that matter the opportunity of overseas travel, and as he remembered it, ‘One of the major advantages of touring was being able to just turn off the rest of the world for a few weeks.’ The technology of the day helped reinforce this sense of isolation. ‘Back then, neither the power of the BBC transmitters nor the efficiency of the