Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

'Fascinating.' - Daily Mail 'An incredible story' - Daily Mirror The period after the First World War was a golden age for the confidence man. 'A new kind of entrepreneur is stirring amongst us,' The Times wrote in 1919. 'He is prone to the most detestable tactics, and is a stranger to charity and public spirit. One may nonetheless note his acuity in separating others from their money.' Enter Victor Lustig (not his real name). An Austro-Hungarian with a dark streak, by the age of sixteen he had learned how to hustle at billiards and lay odds at the local racecourse. By nineteen he had acquired a livid facial scar in an altercation with a jealous husband. That blemish aside, he was a man of athletic good looks, with a taste for larceny and foreign intrigue. He spoke six languages and went under nearly as many aliases in the course of a continent-hopping life that also saw him act as a double (or possibly triple) agent. Along the way, he found time to dupe an impressive variety of banks and hotels on both sides of the Atlantic; to escape from no fewer than three supposedly impregnable prisons; and to swindle Al Capone out of thousands of dollars, while living to tell the tale. Undoubtedly the greatest of his hoaxes was the sale, to a wealthy but gullible Parisian scrap-metal dealer, of the Eiffel Tower in 1925. In a narrative that thrills like a crime caper, best-selling biographer Christopher Sandford draws on newly released documents to tell the whole story of the greatest conman of the twentieth century.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 487

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

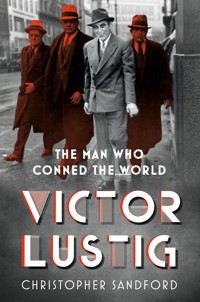

Cover photo: Victor Lustig escorted by police in 1935. © TopFoto/PA Images

First published 2021

This paperback edition first published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Christopher Sandford, 2021, 2024

The right of Christopher Sandford to be identified as the Authorof this work has been asserted in accordance with theCopyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented,including photocopying and recording, or in any informationstorage or retrieval system, without the permission in writingfrom the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 771 1

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

To Jo and David

‘Worth [goes] on foot, and rascals in a coach.’

John Dryden

Victor Lustig’s ‘Ten Commandments of the Con’:

1. Be a patient listener (it is this, not fast talking, that gets a conman his coups).

2. Never look bored.

3. Wait for the other person to reveal any political opinions, then agree with them.

4. Let them reveal religious views, then have the same ones.

5. Hint at sex talk, but don’t follow it up unless the other fellow shows a strong interest.

6. Never discuss health, unless some special concern is shown.

7. Never pry into a person’s personal circumstances (they’ll tell you eventually).

8. Never boast; just let your importance be quietly obvious.

9. Never be untidy.

10. Never get drunk.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

List of Illustrations

1 The Age of Illusion

2 Bohemian Rhapsody

3 A Mask to Show the World

4 The Private Mint

5 French Connection

6 Conning Capone

7 Going South

8 Escape from New York

9 The Rock

Sources and Chapter Notes

Select Bibliography

About the Author

Also by Christopher Sandford

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Victor Lustig used to observe that writers always say they’re aiming to entertain the widest possible audience but they’re in fact in it chiefly for their own amusement. In this context I should immediately acknowledge that the book you’re now holding was largely written during the great lockdown of 2020–21, and as such gave me a daily purpose in life other than obsessing about the correct use of face masks or the latest protocol on social distancing. Even so, I hope you won’t find the story that follows to be entirely without wider merit. Perhaps one of the consolations of getting on a bit is that you tend to clarify in your own mind what’s good and what’s not, and I thus brazenly offer the opinion that this book at least avoids any conspicuous falling off from the modest standards of its predecessors. In fact, further throwing caution to the wind, I can nominate it as my personal favourite. Nonetheless, it goes without saying that none of the names listed below can be blamed for the shortcomings of the text. They are mine alone.

For archive material, input or advice I should thank, professionally: AbeBooks; Alcatraz Archives; Alibris; America; Atlantic Monthly; Bonham’s; Book Depository; Bookfinder; the British Library; the British Newspaper Library; Central Lutheran; Chronicles; Common Ground; the Cricketer International; the Cricket Society; the Daily Mail; the Davenport Hotel; Emerald Downs; the FBI’s Freedom of Information Division; Dominic Farr; Garden Court Hotel; the General Register Office; Grumbles; Hansard; Hedgehog Review; The History Press; Michael Hurley; Jane Jamieson; Barbara Levy; the Library of Congress; Sue Lynch; Christine McMorris; Missouri State Department of Health; the Mitchell Library, Glasgow; Modern Age; the National Archives; the National Gallery; National Review; the 1976 Coalition; the Oldie; Tim Reidy; Renton Public Library; Rebecca Romney; Jane Rosen; St Mary’s Hospital, Paddington; Sandy Cove Inn, Oregon; Seaside Library, Oregon; Seattle C.C.; Seattle Mariners; the Seattle Times; the Spectator; Liz Street; Andrew Stuart; US National Archives/Records of the Bureau of Prisons; Unity Museum, Seattle; University of Montana; University of Washington; Vital Records; Douglas Williford; Wisden Cricket Monthly; Qona Wright; and Simon Wright.

And personally: Tony An; Rev. Maynard Atik; Pete Barnes; Carlos Beltran; Alison Bent; Rob Boddie; Geoff and Emma Boycott; Robert and Hilary Bruce; Jon Burke; John Bush; Lincoln Callaghan; Don Carson; Steve Cropper; Celia Culpan; the Daudet family; Monty Dennison; Ted Dexter; Chris Difford; Micky Dolenz; the Dowdall family; Barbara and the late John Dungee; Jon Filby; Malcolm Galfe; Tony Gill; James Graham; Freddy Gray; Jeff and Rita Griffin; Steve and Jo Hackett; Peter Hain; Nigel Hancock; Hermino; Alastair Hignell; Charles Hillman; Alex Holmes; Jo Jacobius; Mick Jagger; Julian James; Robin B. James; Jo Johnson; Lincoln Kamell; Aslam Khan; Imran Khan; Carol Lamb; Terry Lambert; Belinda Lawson; Eugene Lemcio; Todd Linse; the Lorimer family; Nick Lowe; Robert Dean Lurie; Les McBride; Dan McCarthy; Charles McIntosh; Dennis McNally; the Macris; Lee Mattson; Jim Meyersahm; Jerry Miller; Sheila Mohn; Yvette Montague; the Morgans; Harry Mount; Colleen and the late John Murray; Greg Nowak; Chuck Ogmund; Phil Oppenheim; Valya Page; Peter Parfitt; Robin and Lucinda Parish; Owen Paterson; Bill Payne; Rick Pearson; Peter Perchard; Marlys and the late Chris Pickrell; Pat Pocock, Roman Polanski; Debbie Poulsen; Robert and Jewell Prins; the Prins family; the late Christopher Riley; Neil Robinson; Ailsa Rushbrooke; Debbie Saks; Sam; the late Sefton Sandford; Sue Sandford; Peter Scaramanga; the late Dennis Silk; Silver Platters; Pat Simmons; the Smith family; Chris Spedding; Debbie Standish; the Stanley family; David Starkey; the late Thaddeus Stuart; Jack Surendranath; Belinda and Ian Taylor; Millie Thompson; Hugh Turbervill; Derek Turner; the late Ben and Mary Tyvand; Diana Villar; Ross Viner; Lisbeth Vogl; Phil Walker; Edward Welsch; Alan and Rogena White; Debbie Wild; the Willis Fleming family; the late Aaron Wolf; Heng and Lang Woon; the Zombies.

My deepest thanks, as always, to Karen and Nicholas Sandford.

C.S.

2021

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

p. ii Victor Lustig, c. 1937 (© Bettman / Getty)

p. 5 Horace Ridler

p. 8 Julius and Ada Zancig

p. 10 Horatio Bottomley

p. 13 Charles Ponzi

p. 23 Hostinné in the early twentieth century (© Lebrecht Music & Arts / Alamy)

p. 45 Virginia Woolf and fellow Dreadnought hoaxers

p. 58 ‘Nicky’ Arnstein, Fanny Brice and family(© Bettmann / Getty)

p. 70 Arnold Rothstein (© Everett Collection / Alamy)

p. 86 J. Edgar Hoover (Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington DC)

p. 113 Ruth Etting

p. 119 Hôtel de Crillon (© Historic Hotels PhotoArchive / Alamy)

p. 126 Eiffel Tower with Citroën display

p. 156 Al Capone

p. 168 Jack ‘Legs’ Diamond (Courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection)

p. 173 Peter Rubano with Marshal Ferdinand Foch and others (Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Washington DC)

p. 196 Ronald Reagan (Courtesy of the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library)

p. 224 Billie Mae Scheible (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

p. 237 Victor Lustig with Robert Godby and Peter Rubano, 1935 (© Keystone-France / Gamma-Keystone / Getty)

p. 247 Victor Lustig’s prison break from a third-floor window (Courtesy of Douglas Williford, US National Archives)

p. 258 Victor Lustig in court, 1935 (© Bettman / Getty)

p. 263 Alcatraz Island (Courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley)

p. 265 Victor Lustig’s cell on Alcatraz

p. 271 Letter by Victor Lustig (Courtesy of Douglas Williford, US National Archives)

p. 275 Victor Lustig imprisoned in Springfield, Missouri (Courtesy of Douglas Williford, US National Archives)

p. 277 Grave of Victor and Roberta Lustig (Rick Gleason)

While every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright holders, the publishers would be pleased to rectify at the earliest opportunity any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

1

THE AGE OF ILLUSION

The period either side of the First World War was a golden age for the confidence man. When you add an inflamed sense of patriotism to heightened levels of anxiety about personal survival, you have conditions uniquely receptive to both the acknowledged masters of reality manipulation and to others experienced in squeezing a defenceless victim in a tight spot. ‘A new kind of entrepreneur is stirring amongst us,’ The Times wrote in March 1919. ‘He is prone to the most detestable tactics, and is a stranger to charity and public spirit. One may nonetheless note his acuity in separating others from their money.’

Arthur John ‘Maundy’ Gregory was one of those men who quickly came to appreciate the unintended consequences of the war. ‘He was a compulsive extortionist of the sort prevalent in the 1920s,’ the Daily News once noted. In time Gregory combined active service in the Irish Guards with a sideline in wistful, snobbish journalism and freelance espionage work against what he saw as the rising threat of worldwide Bolshevism. In practice this meant that he arranged payments to the ruling Liberal party in exchange for peerages, published his own newspaper, and collected information about the sex lives of his political foes for the purpose of blackmailing or otherwise fleecing them. Gregory particularly cultivated the company of the deposed royals who haunted Europe in the post-war years, once touching the exiled crown prince of Greece for a loan secured by the proceeds of a non-existent Bolivian goldmine, and similarly interesting the Empress Maria Fyodorovna, mother of the last Tsar, in a perhaps fanciful scheme to breed pigs for the purpose of pitting them in public mud-wrestling contests against human opponents. Gregory was described as a plump, middle-sized man who always wore an exquisite dove-grey suit and made use of a chauffeured, production-model Bentley saloon. He may conceivably have had something to do with the disappearance of his sworn enemy, the radical politician Victor Grayson, who, receiving a phone call while dining with friends in London’s Leicester Square one evening in September 1920, told his companions that he had to go on a matter of urgency to a nearby hotel, but would be back shortly. He never returned. Gregory himself lived long enough to be declared bankrupt and to move to Paris, where he had the ill luck to be captured by the invading Germans in June 1940. He died in an internment camp the following year, aged 64.

Gregory’s was far from the only case of personal duplicity or commercial opportunism to take place in the pendulum years around the time of the Great War. There was the sad story of Mabel Edith Scott, for example, who married the second Lord Russell in 1890 but went on to spend much of the next decade locked in increasingly bitter litigation with her estranged husband over matters involving his unusual bedroom practices and other intimate conjugal details. In time the unhappy lady was able to divorce Russell and enter into a second marriage with an individual describing himself as Arthurpold Stuart de Modena, an Austrian prince who for never fully explained reasons found himself living above a greengrocer’s shop in Portsmouth. In reality, the groom turned out to be a recently discharged naval rating and sometime valet named Bill Brown, and Lady Russell was not his only wife. ‘He was not inattentive to me,’ in the measured words of one lady read out in court, ‘but he presumed on my generosity.’

At about the same time there was one Stephane Otto, who, posing as a member of the Belgian royal family, got as far as pinning the Order of Leopold on the lapel of the commanding officer of the American Army of Occupation of the Rhine, but who later went to jail in Crewe after being convicted of obtaining 12s 6d from a clergyman. Similarly there was the case of Netley Lucas, a Croydon drifter who set himself up as a displaced Rumanian count and best-selling author in post-war London, until he received eighteen months at the Old Bailey for obtaining £225 by false pretences. ‘There must be a trace of insanity in my brain,’ he confessed disarmingly. Or, across the Atlantic, there was the so-called Jerome Tarbot, who enjoyed a comfortable living as a decorated combat veteran and visiting lecturer on the horrors of the Somme, until War Department investigators outed him as a convicted swindler and serial bigamist named Al Dubois Jr, a draft dodger who had in fact been stealing cars in California at the time he claimed to have been in the killing fields of France.

The above list is far from comprehensive. What strikes the observer today is just how many men and women could be so restlessly inventive in their pursuit of the brazen personal imposture or the deft financial shakedown. The whole concept of the creative extraction of funds was one that was painfully familiar to a generation coming of age in the early years of the twentieth century. Such was the range and variety of the scams that it sometimes seems surprising that anyone could have emerged from the era with his wallet intact.

Perhaps the most colourful and long-running hoax of the day wasn’t a narrowly commercial one at all, although it could be argued that, over time, whole fortunes were made and lost as a result. It began, instead, at a meeting of immaculately dark-suited and apparently sober-minded men held at the Geological Society in London on 18 December 1912, when a 48-year-old lawyer and amateur palaeontologist named Charles Dawson claimed to have discovered bone fragments at a gravel pit near his home at Piltdown, West Sussex, and that these had ‘terrific significance’ for our understanding of man’s evolution.

At the same meeting, Arthur Smith Woodward, curator of the geological department at the British Museum, announced that a reconstruction of the fragments had been prepared, and that a resulting ‘human-like’ skull, thought to be some 600,000 years old, was all but indistinguishable from that of a modern chimpanzee. Dawson and Woodward went on to claim that ‘Piltdown Man’ represented no less than a genetic missing link between apes and humans, and by extension a denial of the biblical story of creation, a thesis much of the more progressive element of the press was happy to accept.

It would be forty-one years before new scientific dating techniques conclusively proved that Dawson’s find was a hoax. The Piltdown fossils ‘could not possibly form an integral whole’, The Times reported in November 1953. Instead, they consisted of a human skull of medieval age, the jawbone of an eighteenth-century orangutan, and several assorted modern baboon teeth. There was also a bone chip determined to have come from an extinct species of elephant unique to the plains of Tunisia. Only a brief microscopic examination was required to show that several jaw fragments presented by Dawson had been filed down to give them a shape associated with that of a human. A sculpted bone found at the original site in Sussex, and said by the New York Times to be ‘a wonderfully preserved Neanderthal hunting or sporting tool’ – a sort of primitive cricket bat – had in fact been carved with an ‘implement like a Swiss army knife’ in the years around 1911 or 1912. In short order, Piltdown Man was unceremoniously removed from display and consigned to a metal box in the basement of London’s Natural History Museum. Perhaps the ultimate lesson of the whole escapade is that, as Harry Houdini, himself something of a past master of artifice, once observed: ‘As a rule, I have found the greater brain a man has, and the better he is educated, the easier it is to dupe him.’

The commercial possibilities of the time were captivating, and it was remiss of men not to exploit them to the full, a former British army officer named Horace Ridler later wrote when reflecting on his appearance in the pages of Tatler in 1921, and his subsequent life as a paid guest in the upper echelons of London society. After the war he had gone to the tattooist ‘Professor’ George Burchett in his premises behind Waterloo station and had himself engraved from head to toe with black and white stripes, a protracted and painful business that had taken nearly a year to complete. In time Ridler launched himself on the world as ‘The Great Omi: The Zebra Man’, claiming to have been forcibly disfigured under the most barbaric circumstances by native bushmen in New Guinea. He would tell theatrical booking agents that the best time to reach him direct in his office was between 1 and 2 p.m. every weekday while his secretary was at lunch. Ridler would give them the number of a public phone box in Millwall, and ensconce himself in it for an hour each afternoon heedless of other waiting customers. He went on to become a popular lay preacher and to tour with the Ringling Brothers circus, but was turned down when he tried to re-enlist with the army in 1940. He retired at the height of his fame to Ripe, a small village in Sussex, where he died in 1969 at the age of 77.

Horace Ridler, aka the Great Omi or ‘Zebra Man’.

In broadly the same pseudo-anthropological vein, there was the long, often tragicomic saga of the Cottingley fairies. It began one hot afternoon in July 1917, when 16-year-old Elsie Wright and her 10-year-old cousin Frances Griffiths disappeared with a camera into the glen behind the Wrights’ terraced home in West Yorkshire, and returned with an image that among other things seemed to show Frances leaning on the side of a small hill on which four miniature people were dancing. ‘It is a revelation’, no less an authority than the spiritualist-minded author Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote, when hearing of the affair two years later. There were to be several further twists and turns to the story, but the immediate result was that in 1920 Conan Doyle went into print in a widely syndicated article entitled ‘The Evidence for Fairies’.

The reaction to this was mixed. While many in the worldwide spiritualist movement that sprang up after the First World War championed the two young girls, the newspaper Truth expressed a more widely held view when, in January 1921, it wrote, ‘For the real explanation of these fairy photographs, what is wanted is not a knowledge of occult phenomena but a knowledge of children.’ Even this was mild compared to some of the popular jokes that did the rounds, including the one where Doyle was said to have appeared at the climax of his friend James Barrie’s Peter Pan to lead the audience in a chorus of ‘I do believe in fairies!’ Other wisecracks were less elevated.

Although Conan Doyle went to his grave stubbornly believing in what he called the ‘miracle’ of Cottingley, in 1983 the then elderly women at the heart of the affair admitted that ‘most’ of their original pictures had been faked. The two cousins had cut out illustrations from Princess Mary’s Gift Book, a 1914 annual (in which Doyle himself had published a story) and propped them up with hatpins in the grassy banks behind the Wrights’ house. Frances Griffiths added that the girls had ‘not wanted to embarrass the great men’ who had swallowed their tale, and had been horrified to see it take root for the next sixty years.

Of a more base, sordidly commercial character, there was the sensational case first published in the News of the World on 3 January 1915. It concerned the sorry fate of 38-year-old Margaret Lloyd, née Lofty, a vicar’s daughter who had been married only two weeks earlier. Her 42-year-old husband John, apparently a successful land agent, had discovered her lifeless body in the bath of their lodgings at Bismarck Road in north London. The couple’s landlady testified that she had been ironing in her kitchen that evening when the sound of splashing came from the bathroom above. This was followed by the ‘queer noise of hands rubbing [or] slapping a firm surface’, and then by a deep sigh. A few moments later, she had heard the mournful strains of someone playing ‘Nearer My God, to Thee’ on the organ in the Lloyds’ sitting room. The hymn had ominous associations: legend insists that the ship’s band had been playing the same tune as the RMS Titanic sank into the Atlantic.

Mr Lloyd then came down the stairs and went out, only to ring at the front door a few minutes later, explaining that he had forgotten his key. ‘I’ve bought some tomatoes for Mrs. Lloyd’s supper,’ he announced. ‘Is she down yet?’ Margaret’s death was quickly recorded as misadventure, and her grieving widower collected the £700 life insurance policy he had thoughtfully taken out for her on the day of their wedding. It later emerged that Lloyd, whose real name was George Joseph Smith, had been in the habit of entering into bigamous marriages and disposing of his brides in this manner. He was tried and hanged at Wandsworth Prison for one of what were thought to be as many as six murders.

On a more spiritual if not always charitable level, there were those who exploited the public’s post-war fascination with the idea of a visible afterlife, promising, for only a modest fee, to reunite the living and the dead. It took Houdini himself to put an end to the career of one popular London medium who began her séances by standing nude in a bowl of flour so that she was unable to move around the room without leaving incriminating tracks.

‘She has a tube for her vagin [sic] in which she stashes a pair of silk stockings,’ he explained. ‘When the lights are out, as it is impossible to quit the floor without leaving footprints, she reaches in and gets the silk stockings, puts them on her feet, steps out of the bowl of flour [and] is able to walk around without besmirching the floor or leaving prints. After the materialisation she goes back, takes off her stockings, conceals her load, and – presto! – steps back into the bowl of flour.’

Working much the same angle were the Washington DC-based Julius and Ada Zancig, a husband-and-wife sometime-vaudeville team who in the immediate post-war years advertised themselves as ‘Professional astrologers, tea leaf readers, crystal ball seers, diviners and palmists’. Conan Doyle went to the Zancigs’ home and came away convinced that the couple possessed telepathic powers. Houdini was less impressed, writing that the Zancigs used a system of codes rather than any supernatural gifts to achieve their results, and that even these had been developed only after extended rehearsal. When the first Mrs Zancig had died, her widower ‘took a teenaged street-car conductor from Philadelphia and broke him into the duo,’ Houdini noted. Some acrimony had arisen when the young man later defected from the team and began offering his own mindreading routine, using a trained monkey as a foil. He was replaced by a conjuror known professionally as ‘Syko the Psychic’, who in turn left the act. ‘At that stage, Prof. Zancig came to me for an assistant and I introduced him to an actress,’ Houdini wrote. ‘He said he would guarantee to teach her the code inside a month, but they never came to an agreement on financial matters.’ Where Doyle found Zancig to be a ‘remarkable man [who] undoubtedly enjoyed paranormal or divine powers’, Houdini saw only an old circus sideshow stooge whose new act ‘reflects the modern rage for mediumistic bunco.’

The Zancigs demonstrate their telepathic powers.

A lesser occultist than Zancig, but as great a fraud, was Horatio Bottomley, an English journalist, financier and Liberal politician who in 1912 was bankrupted with liabilities of £233,000, or about £6 million in modern money. He had recently added to his losses when, after bribing all six jockeys in a race at Brighton to finish in a certain order, a heavy sea mist had rolled in and the suddenly blinded riders had failed to follow instructions. Undeterred, Bottomley successfully stood for parliament as an Independent in December 1918 and began offering the public Victory Bonds at the heavily discounted price of £1 each, promising subscribers the chance to enter in an annual draw for prizes – up to £20,000, he said – from the accrued interest. The response to this offer was overwhelming, and Bottomley would have had his hands full had he ever tried to properly administer the scheme. Instead he lavished the funds on luxury cars and thoroughbred racehorses, as well as on mistresses whom he visited in several discreet flats around London. He was eventually sent for trial at the Old Bailey. Even then he conducted himself with a certain élan, securing the judge’s agreement to a fifteen-minute adjournment each day so that he, Bottomley, could drink a pint of champagne, ostensibly for medicinal purposes. Sentenced to seven years, he emerged to launch himself on the London music hall stage of the 1930s, but failed to prosper in his new role. Bottomley died in a charity ward on 26 May 1933, at the age of 73. One obituary called him ‘more a series of public attitudes than a person’.

Horatio Bottomley addresses a wartime recruiting rally in London.

Following in the same long if not distinguished line as Gregory, Bottomley and the rest was Artur Alves Reis, an impoverished Lisbon undertaker’s son who forged himself a diploma from Oxford University and, posing as an accredited government finance ministry official, persuaded a printer to issue him with 200,000 Portuguese banknotes. Reis bought himself old masters, three farms, a taxi fleet and expensive French couture for his wife and numerous mistresses on the proceeds. A contemporary account describes him ‘stroll[ing] the Rua do Salite in a businessman’s double-breasted grey suit, with three-pointed white handkerchief on display in the breast pocket, Malacca cane in hand’. Arrested in December 1925 and sentenced to twenty years, on his release Reis was offered a job advising the state bank on security. He died of a heart attack in June 1955, aged 58.

The equal of them all was Ivar Kreuger, the Swedish-born matchstick king of the post-war world who built himself a marble-floored, 125-room Stockholm office complex as he all but cornered the market for phosphorus-based household combustibles. By 1922 Kreuger had sufficient cash on hand to allow him to lend money to several foreign governments, and was in the habit of transferring funds from one holding company to another with what a judge later called ‘little or no formality’. Some of it went into non-existent client accounts, but more was spent on beautiful women and expensive houses. Kreuger’s penchant for gambling his investors’ money on the foreign exchange markets proved disastrous, however, and he apparently shot himself in March 1932, aged 52, although rumours persist that he was murdered for reasons buried amongst the chaos of his reign as Europe’s most notorious rogue trader.

In the years following the First World War, a lady might have discreetly availed herself of a small mechanical device known as a Pulsocon. Looking rather like a hand-cranked rotary egg whisk, it was officially described as a ‘blood circulator, able to relieve pain, rheumatism, deafness, gout, and many other ailments’, but seems to have been most popular as a prototype vibrator. It was the brainchild of an Irish-born showman called Gerald Macaura. Macaura gave himself the title ‘Doctor’, but he had no medical qualification; nor had he served in the trenches, as he often claimed. Jailed in Paris for practising without a licence, he returned to his native country to promote the merits of his new invention the O’Lectron, which ‘produces both mechanical and magnetic oscillations’, giving man ‘control over the circulation of his blood and the very atoms of which he is composed’. It sold in impressive numbers, allowing Macaura to buy large houses on both sides of the Atlantic, as well as to underwrite a brass band and a first-ever cinema in his home town. Strong, sly, charming, decisive and intolerant of criticism, over the years he successfully sued a number of newspapers and once forced the New York Times to publish a front-page apology for having aired doubts about the O’Lectron. How did he do it? ‘Gerry told them to shut up, so they shut up,’ one Irish justice ministry official explained.

Consumers in the 1920s became accustomed to the miracle health cure or the sure-fire investment opportunity. In the era of dissimulation, it was all part of their daily routine. Perhaps no one was more emblematic of the age than the Italian-born Carlo ‘Charles’ Ponzi (1882–1949), who for a few heady years bestrode the financial malpractice world with his ‘scheme’ to buy up stocks of the humble international reply coupon – a voucher to allow someone in one country to send it to a correspondent in another country – and sell them at a 400 per cent profit. By June 1920 investors were cheerfully paying some $1 million a day to be allowed to participate. In the classic tradition, Ponzi bought himself a fabulous Boston estate, which he staffed with numerous live-in servants and a pack of Doberman guard dogs. One biographer writes: ‘He had an enormous limousine specially built for him, driven by a chauffeur with a footman beside him, both in plum uniforms to match the car.’ It seemed Ponzi had positioned himself exactly where he wished to be – poised to profit from either the naked greed or the naïve enthusiasm of the American consumer of the 1920s.

Charles Ponzi.

Alas, the scheme collapsed just as quickly as it had risen. Later in the summer of 1920 the Boston Post began asking pointed questions about Ponzi’s cash machine, noting that he would have needed to control a minimum of 160 million international reply coupons to have covered his investments. As there were only 27,000 such certificates in worldwide circulation, ‘there would seem to be doubts about the soundness of his basic proposition’, in the Post’s measured words. It all came crashing down for Ponzi later in August 1920 when the same paper revealed that the ‘modern-day King Midas’ was one and the same as the young Montreal bank clerk who had recently been released from a Canadian prison after being convicted of forgery. He was eventually indicted on eighty-six counts of fraud, and served three-and-a-half years of a five-year sentence. It was thought that Ponzi’s investors had collectively lost some $20 million (roughly $500 million today) as a result of his activities. On his release the Massachusetts officials promptly arrested him again for grand larceny.

While awaiting trial, Ponzi moved to Florida and offered investors parcels of ‘prime oceanside real estate’ on which he promised a 200 per cent return within sixty days. In reality it was a scam that sold practically worthless swampland. Following that, Ponzi shaved his head, grew a moustache, and tried to flee the country disguised as a crewman on a merchant ship, but was returned to serve seven more years in jail before emigrating to Brazil. On his death his final estate was valued at $62, which proved just enough to provide a third-class funeral in Rio’s municipal cemetery.

Broadly speaking, there are two distinct kinds of confidence artist: those who aspire to the single, big score, or at least who work one basic angle and then repeat it, with little or no variation, to the bitter end; and others who go in for variety, perhaps truer to the spirit of the scam as an expression of rebellion, of reinvention, and of scandalising the respectable. An example of the former would be Arthur Orton, aka Thomas Castro, the young butcher’s assistant from Wagga Wagga in New South Wales by way of Wapping, east London, who famously came forward claiming to be Roger Tichborne, the shipwrecked heir to the wealthy baronetcy of Tichborne Park in Hampshire. Although the claimant’s manner and bearing were unrefined and he appeared to have both doubled in weight and lost a number of distinguishing tattoos during the years he had wandered around the Australian bush, he gathered support and duly sailed to England. Lady Tichborne initially accepted him as her lost son, although other family members were sceptical that the obese and barely literate Orton might be one and the same as the slight and well-educated Roger Tichborne. Extensive civil and criminal proceedings followed, at the end of which the claimant was tried for perjury under the name of Thomas Castro and sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment. He died on April Fool’s Day, and was given a pauper’s grave without a headstone. It seems Orton wasn’t so much a career confidence man per se as someone who saw his opportunity, however misguided, and took it.

Much the same could be said of Anna Anderson, the young woman who in 1922 emerged from a Berlin mental ward to insist that she was the Grand Duchess Anastasia, youngest daughter of the last Tsar of Russia, who conventional wisdom believed had been murdered by Red Guards along with the rest of her family four years earlier in the basement of a house in the foothills of the Ural mountains 900 miles from Moscow. The German courts were unable to decide Anderson’s claim one way or another, and, after forty years of deliberation, ruled that her case was ‘neither established nor refuted’. Most modern scholars are agreed that she was probably one Franziska Schanzkowska, a wartime Polish factory worker with a history of mental illness.

Perhaps both Orton and Anderson were simply clever and unusually tenacious frauds, or possibly they could be seen as more timeless figures – social anarchists, masters of imposture, the ultimate inappropriate persons. In any case, they surely anticipate our modern celebrity culture, which relentlessly teaches us that we can break free from the mundane or unpalatable reality of our lives and instead be whatever we choose.

By contrast, there are serial grifters such as the Irish-born but truly international man of mystery Michael Dennis Corrigan, who enlivened the legal pages of the world’s press in the 1920s and ’30s. Hailing, like Gerald Macaura, from Cork, he posed successively as a general in the Mexican army, a Chinese warlord, the Soviet Union’s commissar for trade, and an apparently authorised representative of the Rumanian government, mandated to enter into commercial agreements with foreign powers. To call Corrigan the David Bowie of the early twentieth-century flimflam world is to confer a flattering sense of consistency on a man whose personal changes of status were so rapid and extreme that there was only the simple, unifying theme of deceit running as a throughline to confirm that he was the same person. Described as a ‘stolid man of military bearing’, Corrigan went bankrupt while living in London in 1928 with debts of £108,882 and assets of £30. That same year he sold a French businessman sight unseen 550 crates of supposedly high-grade rifles and ammunition, but which turned out on closer inspection to contain only sawdust and bricks. On another occasion, Corrigan played the part of a chief inspector in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police seconded to London, and persuaded a Mayfair jeweller to lend him his stock for a day in order to trap a gang of international thieves. At the time of his eventual arrest he was living in a luxurious Chelsea penthouse, employing a butler and a chauffeur, and apparently happily married to a woman whose own mother he had taken for several thousand pounds in a share fiddle. Facing up to twenty years for fraud, Corrigan hanged himself in his cell with an Old Etonian tie. He left a note for his solicitor saying, ‘I deserve everything for being such a greedy fool … I don’t think I can pay this price.’

An interesting fact about many of the scams seen above, whether of the habitual or more specialised kind, is the almost touching gratitude displayed by at least some of the victims. Horatio Bottlomley’s career is evidence not only of personal chutzpah on a grand scale but of the extent to which the public will always be charmed by a plausible rogue. ‘I like this man,’ one man told his family after being fleeced of his life savings. ‘I have heard him speak. I won’t have you say a word against him. Anyone who utters a breath against Bottomley I will quarrel with. I am not sorry I lent [sic] him the money, and I would do it again.’

It was the same story with Charles Ponzi. Even in prison he continued to receive Christmas cards from dozens of his defrauded customers, as well as requests from many others to take more of their money. When the French police first came for Gerald Macaura they were attacked by a large crowd of men and, more particularly, women gathered in the street, so sure were they of their hero’s innocence. The obituary in the daily News Chronicle attempted to make sense of Michael Corrigan’s life in a long notice that wasn’t uncritical of Corrigan’s habitual attempts to hoodwink the public. The paper’s final conclusion, nevertheless, was that the deceased had been ‘at heart a thoroughly credible and strangely likeable character who [had] targeted well-heeled institutions and governments rather than the common man’. The lesson seems to be that one mistake in public life can often lead to oblivion, but that even today many of us find the crooked charmer such as Macaura or Bottomley a rather endearing figure.

Another theme observable in the careers of Corrigan and his like is that they rarely seem to end well. At heart the confidence man really deals in the disintegration of lives, his own as well as his victims’. With just a touch of colour, Corrigan once remarked from his cell that, ‘Heaven and hell [were] both in evidence during my mortal walk.’ The opportunity to travel the world, often in the guise of a visiting foreign dignitary, and be treated with a ‘warmth and respect denied the common pilgrim’ provided a glimpse of heaven. There was his late 1930s tour of Leningrad, for instance, where he gamely sought to interest the municipal authorities in a heavily discounted consignment of asbestos padding for their new city hall. In between being wined and dined by his Soviet hosts, Corrigan took the time to write in his journal of the ‘rustling woods, green fields waving in the wind, spruce white-painted churches and red-roofed, oak-beamed peasant cottages trimmed in shades of pink and ochre’. These were not the typical sights or experiences of the average illegitimately born working-class Irishman of his day.

Hell was provided by Brixton Jail. Corrigan spent some weeks confined there over the winter of 1945–46 while awaiting trial at the Old Bailey. He had finally been incarcerated after being charged with posing as a member of the Guatemalan government visiting London as part of an elaborate scam to supply the Ministry of Defence with 300 tons of ‘high-quality native rosewood’ for the construction of wartime fighter aircraft. Corrigan had previously secured £2,000 from the King’s personal dentist as a loan towards his modest accommodation and travel expenses while concluding the deal. Brixton was a ‘squalid and inhumane existence, caged up like a beast 23 hours a day,’ he wrote. At one stage the resident of the next cell had been a well-born, 34-year-old American embassy clerk named Tyler Kent. Kent had been picked up in 1940 under the Official Secrets Act, shouting through the letterbox of his London flat to inform the first police on the scene that they were Communists who themselves deserved to be arrested. After breaking down the door and taking the suspect into custody, the authorities had found 1,929 official or semi-official documents, as well as what the Home Office report termed ‘a female clad in the most sparing of garments’ on the premises. The former included copies of secret cables between Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt that would seem to have been in breach of the strict US neutrality laws. It says something for the inveterate schemer in Corrigan that he went on to persuade both Kent and a number of other Brixton inmates to invest in an apparently legitimate mortgage company, which he marketed under the slogan, ‘Own your own house and be a free man’. This, too, ultimately failed to prosper, and there had been ‘grim scenes’, he admitted, when some of the disgruntled subscribers to Corrigan’s project had confronted him about it in the prison showers.

Like all confidence men, Corrigan loathed being alone. As the door of his single cell slammed behind him on the dark night of 15 October 1946 he was left to write of the ‘self-imposed hades’ of his recent life, adding somewhat oddly that ‘these blasted krauts who [had] so terrorised the world surely deserve the rope more than me’. Corrigan could have had no way of knowing that Hermann Göring, the most senior surviving such Nazi official, would commit suicide in his own prison cell some 600 miles away in Nuremberg on the same night he did. It was much the same sorry tale for Maundy Gregory, Horatio Bottomley, Artur Reis, Ivar Kreuger and Charles Ponzi – not to mention George Joseph Smith – as well as many others. For the truly dedicated career confidence man it would seem that disappointment and ultimate self-destruction are the rule, and prolonged professional or personal contentment the exception.

A final generic thought on the times in which most if not all of the above names came to prominence. One of the striking characteristics of the 1920s is the unparalleled rapidity and unanimity with which millions of men and women, on both sides of the Atlantic, opened their wallets to an exceptional number of charlatans and hoaxers. Whether it was the frenzied speculation in worthless American swampland, or the mania in the upper echelons of British society for quack doctors and miracle health cures, the immediate post-war generation seemed to be in thrall to almost every halfway plausible huckster to appear over the horizon. Without delving too far into the briar patch of psychiatry, it’s possible to generalise that a disillusioned world fed on war, self-denial and conformity was revolting against the diminished prospects in life it had long been forced to endure. For years people had been spiritually and materially starved. They had seen their ideals and illusions and hopes one by one worn away by the corrosive influence of events and ideas – by the horrors of the war and its aftermath, by scientific doctrines and psychological themes that undermined their religion and shook the guardrails defining the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, by the spectacle of graft in politics and a seemingly daily newspaper diet of smut and murder, and then in turn by a widespread if by no means universal decade of prosperity, during which the businessman was, as the economist Stuart Chase put it, ‘the dictator of all our destinies’, ousting ‘the statesman, the priest, the philosopher, as the creator of standards of ethics and behaviour’ and becoming ‘the final word on the conduct of our society’.

In short, a large number of people, in all walks of life, were in an unusually febrile mood following the years of sacrifice, and now had unprecedented amounts of cash at their disposal. These were conditions that would seem to have been tailor-made for the type of smooth-talking individual tuned in to the commercial opportunities of the age – the sort of person who understands that it’s when we’re most emotionally vulnerable, or when the times are most volatile, that we’re most grateful for the kind stranger who shows up with the easy solution, and who has both the gall and the resources to carry it all off.

In assessing the career of that ultimate emblematic criminal of the day, Victor Lustig, we should acknowledge that he was one of those marginal figures who, as the police say, had form. In fact, he epitomised the serial offender. By the age of 16, while still at a state-run boarding school in Dresden, Lustig already knew how to hustle an older opponent at billiards, understood both how to lay odds at the local racecourse and rapidly absent himself from the scene if the need arose, was on terms of some familiarity with what he called the ‘incurable romantics’ who loitered around doorways in the city centre dressed in tight skirts, and, to quote his subsequent arrest file, generally preferred the company of the ‘louche and mutant types who [sat] drinking away the afternoon’ rather than the more conventional adolescent pursuits of his day.

Despite all this, Lustig could speak fluent German, Italian, Hungarian, French and English while still a schoolboy, loved to watch the opera, and taught himself to play competitive-level chess. As he remarked in a letter he wrote from a prison cell, ‘I have a consuming thirst for knowledge, and have always been able to find it, one way or another.’ The author Floyd Miller later noted that the man who had gone on to become the quarry of police forces all over the world was ‘the cleverest and most resourceful exploiter of human frailty in the history of crime’.

One stormy night in November 1906, the teenaged Lustig took a young girlfriend with him to a production of Wagner’s Rienzi at the ornate Semperoper theatre in Dresden. The girl was impressed both by her companion’s obvious good taste and abundant charm, but she grew uneasy when, following the performance, he silently led her on to a nearby rooftop, grasped her hand tightly as they stood staring down on the city lights and in a voice ‘hoarse with passion’ began to speak of his hopes and fears for a life that, like that of the fictional Rienzi, he was convinced fate had singled out for the wildest extremes of success and disaster. With his eyes narrowed and the collar of his black opera cloak turned up in the chill night air, he seemed ‘almost possessed’, wrote the girl, who put an end to their relationship a short time later.

Here is what Lustig’s first and most tenacious wife, the former Roberta Noret of Kansas, had to say of him:

He could be terrible. His dark streak frightened even his friends. And he remembered. He never missed anything you said or did.

But although Lustig had a sort of personal blacklist, Roberta added:

If, on the other hand, you were on his good side, he treated you like a brother. If you were his friend, nothing was too much trouble. He would only take from those who deserved it. His life’s purpose was to rob the rich and help the needy. If you were on his white list, you could do no wrong. There was no grey list. He was incapable of grey. It was always either black or white.

It is debatable how far Lustig’s benevolence truly extended beyond himself and his immediate circle. But there’s no doubt that he was one of those individuals who opt for a full-blooded approach to life rather than what he termed a ‘timid but steady progress [towards] the grave’. When such a character is both supremely intelligent and intensely ambitious and he is, like Lustig, possessed of almost messianic zeal for his life’s goal of separating people from their money, matched only by that of the world’s police forces for stopping him, then the stage is set for high drama.

2

BOHEMIAN RHAPSODY

Victor Lustig was not born either in New York City or Paris on 4 January 1891. The date and one or other of the locations appear in several records, primarily rap sheets, circulated during his lifetime. Perhaps they help form an appropriately hazy starting point for a career dedicated to the art of deception. He certainly never went out of his way to correct the misapprehension, which arose out of a combination of clerical error and his own reluctance to dwell on his immigrant past or admit his real age. On the day in May 1935 when he was detained in New York, he signed a statement with the inscription: ‘Count Robert V. Miller-Lustig, b. Jan 4 ’91, NYC’, and those details duly appeared in the indictment read out in the federal court proceedings against him later in the autumn, possibly giving him a last sardonic laugh at the expense of the authorities he had so successfully misled for much of the previous twenty-five years.

Victor Lustig wasn’t even his real name, of course. Somehow aptly, his parents christened him Robbe, today’s Robert, and as a family they generally went by variants of Molnar, Mueller or Miller. A land tax assessment issued to their home in December 1897 is addressed to one ‘L. Muller’, although in those days spelling was still generally as flexible as in pre-Chaucerian Britain. Perhaps it hardly matters in the case of a man who eventually enjoyed some forty-five different aliases.

Victor Lustig, as we’ll call him, was born, the middle of three children, in the small family home in Hostinné, Bohemia, one of those marginal places in central Europe that flit back and forth between countries depending on the fortunes of war. At the time, it was a hamlet of some 6,000 souls, set close to the junction of the Elbe and Čistá rivers in what is now the Czech Republic. In 1841, Hostinné had also been the birthplace of Karel Klíč, the inventor of the photogravure process that in later years made millionaires of several counterfeiters of the world’s banknotes, Lustig himself prominently among them. In the late nineteenth century the town was spread out around a number of bustling squares in a haphazard jumble of shops, bazaars, tenements, bungalows, bridges and richly aromatic livestock pens. There was also a Gothic city hall set up on a rocky spur, fronted by a gold-faced clock tower and topped by domes pointed like witches’ hats. Visiting Hostinné in 1893, Klíč wrote of the town’s striking architectural contrasts, ‘a glittering visual patisserie’ of soaring medieval spires and ‘crude wooden shacks with animal swamps that bubbled and stank like stewing tripe’. Gritty snow hillocks formed every winter along the unpaved streets, and sewage ran raw and braided in the gutters. Many of the town’s adult inhabitants were illiterate, or semi-literate at best, and had been born as serfs. In all, it was the kind of place that teaches a boy to be practical while it forces him to dream of other, headier realities. Lustig was born here on the Saturday morning of 4 January 1890. There is no evidence that either he or any of his family were ever granted the title ‘Count’.

Hostinné’s Gothic city hall by moonlight.

His father, Ludwig, was of ‘low peasant stock’, Victor later recalled, although other accounts insist that he served as the mayor of Hostinné. Perhaps both versions are true. It’s known that the family lived in a four-roomed stone house on Tyrsovy, a narrow street winding up by the river north of the main market square, and that neither the home itself nor the immediate vicinity had any pretension to elegance. On the day Victor was born the weather broke in a thick shawl of snow. Jugs of river water had to be boiled over a peat fire in the parlour to help with the delivery. At that time of the year, a greasy, yellow fog often descended by day, leaving spectacular rime deposits on Hostinné’s streets. At night the Čistá froze solid and the cold seemed to have the pygmy’s power of shrinking skin.

Ludwig was a small, squat, cynically humorous man. Whatever his true status in life, he doesn’t always make a sympathetic figure in Lustig biographies. We know that he was relatively well groomed, irrepressibly proud of his dark cavalryman’s moustache, responsible and apparently honest, but also that he was gruff, bad-tempered and stingy – a ‘clenched fist’ in one account. Ludwig’s granddaughter Betty remembered him as a tradesman, dealing mainly in pipes and tobacco, and adds that he had forced the young Victor to take violin lessons, which he hated. In a distressing scene, she writes that following one clash of wills on the subject, ‘Ludwig carefully raised the instrument, pointing to the ceiling, and, with all the force of his more than average strength, every muscle in his body taut, brought it down on the boy’s head.’

Ludwig had, it’s agreed, a way with women, a talent Victor would inherit from him. Mostly, though, the son consciously tried to be as unlike his father as possible. Where Ludwig was frugal, Victor prided himself on spending money the second he got it, and often even earlier. The boy was told that the novels of Émile Zola and his school were corrupting filth, and at the age of 8 he had to sign a solemn oath that he would abstain from alcohol and faithfully attend the Catholic Church. The elder Lustig was ‘used to dominating all scenes in which he appeared,’ Betty wrote. Unsurprisingly, Victor never forgot the violin incident: for the rest of his life authority figures would rarely evoke anything but contempt. In later years he complained bitterly that Ludwig had frequently thrashed him ‘unmercifully with a bull whip’, although in the rural Bohemia of those days severe beatings of children weren’t uncommon, being considered good for the soul. The violence apparently extended to Ludwig’s docile wife Amelia, known as Fanny, fifteen years younger than her husband, and if true must have made an indelible impression on Victor.

Weighing up the evidence, it seems fair to say that the family were of modest means, certainly, but not the absolute dregs of Habsburg society as it was constituted in the 1890s. Ludwig’s granddaughter says that his tobacco business often took him on lucrative trips as far afield as Zürich or Prague. At the age of 7, Victor accompanied his father on the train to Paris, a city that later struck him as exquisite in its central areas, but elsewhere a ‘sad, soiled place that slithered around in a sea of immorality’, to which in time he duly contributed. Victor was considered bright but wayward as a child. Early on he showed signs of being both self-willed and resistant to the discipline of regular work. He lasted only one day at the Hostinné infants’ school, where he was expelled for saying ‘Leck mich am Arsch’ – roughly translated as ‘Kiss my ass’ – to his female teacher. After that he transferred to a one-room establishment located 3 miles away down a dirt path in Čermná, which he reached each day on foot. Victor’s parents reportedly separated only a year later, when he was 8, although the Habsburg census taken in December 1900 shows all five family members, a mule and a 15-year-old ‘idiot-girl’ named Klara Muller – possibly a cousin – living together at the Tyrsovy residence.

Even at that early age there was something in the dark-eyed youngster’s look that set him apart from his schoolmates. In the form picture that year at Čermná he stands in the centre of the front row, looking several years older than his contemporaries, chin up, frowning. ‘We all liked him, but the teachers didn’t,’ his friend Karl Harrer wrote. ‘He had “guts”. He could impersonate different people’s voices, march[ing] around the play yard shouting mad army commands with a tin saucepan on his head. Somehow he seemed a lot wiser than us. I remember he was the first person who told me in detail about the difference between boys and girls, [which] was very impressive.’

Perhaps reflecting the authorities’ less appreciative view, Lustig’s July 1902 school report called him ‘Retarded morally, an idiot in other respects’. Such things tended to be more bluntly stated than they are today. At 13 he was tall and heavyset with an engaging smile that carried a glint of rebellion. Talented at boxing, he was not otherwise very athletically gifted. From early childhood he was a martyr to his sinuses, sometimes emitting a harsh, guttural snort that Harrer compared to the ‘violent peal of a blocked sewer’ as he painfully cleared his throat. Although Victor always seemed strong, he was sick a great deal, a reality he hid from his school friends. Migraines continued to plague him, his hands mysteriously swelled up in the summer months, and, on a trip to Prague, he fell and broke his collarbone. Nonetheless, he hated to miss even a day of school, where he had a perfect attendance record. Karl Harrer once watched in wonder as his friend came ‘bound[ing] up to the front gate one morning, like a dog off the leash, and then only minutes later, once out of view, slowly shuffled up a muddy back path to the latrine one limping step at a time’.

Harrer himself, who was a year younger, provided – in addition to Lustig’s little brother Emil – the necessary audience for the stream of fantasy he poured out. In what way Victor was to express his latent genius was unclear – whether as artist, actor, inventor (he produced elaborate plans for a flying bicycle), boxer or poet – but it was always on his own terms, not as a team player. Socially he was quite precocious. In later and less-reticent times several American ladies would come forward to describe, often in well-remembered detail, how Lustig had so thoroughly corrupted them. Leaving aside his own moral shortcomings, with certain rare exceptions the complainants’ principal qualities would seem to have been vapidity, greed and physical beauty. As a 14-year-old schoolboy Lustig apparently once persuaded a village girl of his own age to accompany him back to his empty family home, where he made love to her on the floor in front of a large antique mirror propped up against the wall. Immediately afterwards he found that he wanted to be alone. ‘I’ve got to run,’ he announced. Lustig seems not to have understood how cutting his remark was, or that leaving so abruptly might have hurt anyone’s feelings, because he reportedly said the same thing to a number of subsequent partners – indeed, it became something of a catchphrase for him later in life.

Betty Lustig writes that when her father was 12 he ran away from home and in due course found himself living 700 miles away in Paris. ‘There, for two months, he lodged in various quarters … He even found shelter in a house of prostitution, where the Madam was kind to him and never once let him be harmed. Finally, the police found him and returned him to his father.’