Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

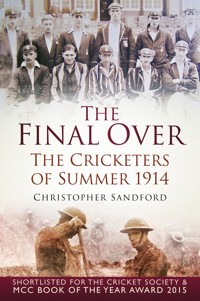

Shortlisted for the 2015 Cricket Society and MCC Book of the Year Award.Shortlisted for the Cross British Sports Book of the Year 2015 (Cricket category). August 1914 brought an end to the 'Golden Age' of English cricket. At least 210 professional cricketers (out of a total of 278 registered) signed up to fight, of whom thirty-four were killed. However, that period and those men were far more than merely statistics: here we follow in intimate detail not only the cricketers of that fateful last summer before the war, but also the simple pleasures and daily struggles of their family lives and the whole fabric of English social life as it existed on the eve of that cataclysm: the First World War. With unprecedented access to personal and war diaries, and other papers, Sandford expertly recounts the stories of such greats as Hon. Lionel Tennyson, as he moves virtually overnight from the round of Chelsea and Mayfair parties into the front line at the Marne; the violin-playing bowler Colin Blythe, who asked to be moved up to a front-line unit at Passchendaele, following the death in action of his brother, with tragic consequences; and the widely popular Hampshire amateur player Robert Jesson, whose sometimes comic, frequently horrific and always enthralling experiences of the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign are vividly brought to life. The Final Over is undoubtedly a gripping, moving and fully human account of this most poignant summer of the twentieth century, both on and off the field of play.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 590

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

To Sefton Sandford

1925–2012

‘The cricket’s gone; we only hear machines.’

David McCord

III

‘If it were not for the war,

This war

Would suit me down to the ground.’

Dorothy Sayers

III

‘Something’s going to happen, Blue.’

Australian bowler ‘Tibby’ Cotter, moments before hisdeath in action

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Quote

Preface

1 Golden Age

2 Spring

3 Early Summer

4 Midsummer

5 High Summer

6 Blood-red Sunset over the Thames

7 To Arms

8 ‘16 Dead Englishmen’

9 Endgame

Appendix: Roll of Honour

Bibliography

Sources and Chapter Notes

Plates

Copyright

PREFACE

Afew years ago I was watching my local cricket club in action when a man of about middle age, coated in designer stubble and with several bits of metal puncturing his face, clad only in voluminous army-surplus shorts, came by to chat. I should mention that the club is in Seattle, USA. After watching the game for a few minutes with an increasingly bemused expression, he asked the inevitable question: could I please explain the attraction? I made the usual not very successful attempt by an Englishman to decipher the game of cricket to an American.The man left, rocked to his core that one batsman could score as many as 20 or 30 in a single game and, I think, also muttering something about a contest that can last five days and end in a draw not immediately conforming to American-spectator standards of entertainment. It was only later, giving the matter some more thought, that I realised the answer to the question was in fact security. With one or two rare exceptions, I’ve always felt completely and contentedly safe while at a cricket match: not only physically safe, but safe from the faintly nagging feeling that something, somewhere, is about to happen to my ultimate detriment. For me, it’s a sort of holiday from the real world. So long as I’m at the back of a stand at Lord’s or the Oval, or sprawled under the boundary trees in Seattle, nothing can go seriously wrong.

All of which is fine as far as it goes. Perhaps one needs to be mildly paranoid about the outside world in the first place in order to find a sanctuary in cricket. It is worth mentioning only because of the very obvious contrast to the players and spectators of the game in England exactly a hundred years ago; for many of them, life could hardly have been less safe or secure as the clock wound down inexorably to the first week of August. It only adds to the poignancy of the story to see how few of them had any inkling of disaster until almost the last instant. Four out of five adults in Britain, according to one study, actually and consciously disbelieved that there would be a general war right up until the moment on the bank holiday Friday of 31 July 1914 when the Stock Exchange closed down early for the first time in its 113-year modern history. ‘If the bankers were worried, so should we be’, said Harold Wright, an opening batsman at Leicestershire. Just over a year later, Wright was mown down in the sustained and ultimately futile Allied offensive at Gallipoli. He was 31.

The Final Over is not a statistical, or necessarily a chronological, record of every first-class cricket match played in England that season. There are other books, notably Wisden, that do the job admirably. It does, however, take the view that cricket is a reflection of life, and that by and large cricketers reacted to the crisis in exactly the same way as everyone else, no better and no worse. The records show that they volunteered at broadly the same rate as other young men, and that they died, too, in proportion: in coldly statistical terms, roughly one in nine of those who fought did not return alive. This book follows some of those individuals and their families on and off the cricket field, and ultimately onto the bloody beaches of Gallipoli, or into the trenches of Flanders that had been churned into a sea of mud and rubble.

The Final Over attempts to shed light on the ‘golden age’ of English cricket; to demonstrate what it meant to be an ‘amateur’ or a ‘professional’ player a hundred years ago; and to show again the arbitrary nature of war, where one man could fall and the man next to him come home and live to be 90.

And there were other casualties. The outbreak of war weighed heavily on some of the recently retired greats of cricket, many of them already struggling to cope with what Andrew Stoddart, the former England captain, called ‘life after death’. As we’ll see, the implications for several of these men would be devastating. The notion of an industry or profession jettisoning some of its most distinguished practitioners in their early middle age may also have a certain resonance today.

Finally, this is neither a political nor a military history of the First World War. There is no shortage of published work on the subject, and a very few suggestions can be found in the bibliography at the end of the book. I should also make clear that it is not a comprehensive list of all worldwide cricketers in some way affected by the war, and no slight is intended on any name omitted. My own main interest is the narrower but hopefully timely one of showing how certain British public figures, particularly sportsmen, reacted to the events of that summer. During the two years I was writing the book, I sometimes thought back to an earlier work I did on Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini, a relationship that at first prospered and then imploded spectacularly in the 1920s. Of his kind, Conan Doyle (a keen cricketer) was perhaps typical of the sort of instinctive patriot whose conceptions of war were shaped more by the past than by premonitions of the future. In the period from November 1914 to November 1918, he lost eleven of his immediate family members, including his eldest son, to combat or disease. Doyle, it seems to me, embodied some of the paradoxes brought about by the First World War; the creator of English literature’s most famous human calculating machine, he spent the rest of his life attempting to contact dead people. I mention it just to show how the broad events treated in this book made some men and broke so many others. If nothing else, I have tried to portray the individuals seen here in the context of how they viewed the partly ludicrous, partly horrific acts of that summer, and not necessarily as we see them today. Although I hesitate to use the word ‘enjoyable’, it was a strangely absorbing book to write – rather more so, I admit, than my recent biography of the Rolling Stones, a group of undoubted charm, whose essential effect on their audience could surely be reproduced by stewards walking up and down the aisles jolting random concert-goers with cattle prods. I only wish I could blame someone listed below for the shortcomings of the text. They are mine alone.

For archive material, input or advice I should thank, institutionally: The American Conservative, Blackheath RFC, Bookcase, Bright Lights, the British Library, the British Museum, Cambridge University Library, CBS News, Chronicles, Cricket Australia, CricInfo, the Cricket Society, Daily Mail, Daily Telegraph, ECB, Essex CCC, General Register Office, Gethsemane Lutheran Church, Hampshire CCC, HMS Protector Association, the Imperial War Museum, Kent CCC, the MCC Library, Middlesex CCC, the Missoulian, National Army Museum, Navy News, Pip, Public Records Office, Radley College, Renton Library, Rugby School, St Peter and Paul Church Tonbridge, Seattle Cricket Club, Seattle Mariners, Seattle Public Library, Somerset CCC, South Africa Cricket Association, Sportspages, Surrey CCC, Surrey History Centre, Taki’s Magazine, UK National Archives, USA Cricket Association, Warwickshire CCC, Yorkshire CCC.

Professionally: Wendy Adams, Christina Alder, Dave Allen, Jeffrey Archer, Stanley Booth, Paul Bradley, Phil Britt, Paul Brooke, Susan Carey, Dan Chernow, Kathryn Churchouse, Allan Clarke, Paul Clements, the Cricket Writers’ Club, Robert Curphey, Curtis Brown, Paul Darlow, Alan Deane, Tony Debenham, Andrew Dellow, Mike Dent, Michael Dorr, Lauren Dwyer, Alan Edwards, the late Godfrey Evans, Rex Evans, Mike Fargo, Tom Finn, Judy Flanders, Tom Fleming, John Fraser, Bill Furmedge, Ann Gammie, Jim Geller, Tony Gill, Freddy Gray, Ryan Grice, the late Reg Hayter, Michael Heath, Andrew Hignell, Jim Hoven, Emily Hunt, the late Len Hutton, Neil Jenkinson, Mike Jones, Edith Keep, David Kelly, Imran Khan, Max King, Alan Lane, Barbara Levy, Cindy Link, John Major, Robert Mann, Ian Marshall, the late Christopher Martin-Jenkins, Dave Mason, Colin Midson, Jo Miller, Nicola Nye, Maureen O’Donnell, Orbis, Michael Owen-Smith, Max Paley, Palgrave Macmillan, David Pracy, Katharina Rae, Neil Rand, Andrew Renshaw, Jim Repard, Mike Richards, Scott P. Richert, David Robertson, Neil Robinson, Peter Robinson, Jane Rosen, Malcolm Rowley, Stephen Saunders, Paul Shelley, Don Short, Ron Simms, Ben Slight, A.C. Smith, Peter Smith, Andrew Stuart, Janet Tayler, Don Taylor, Andrew Trigg, Charles Vann, Suzanne Walker, Carol Ward, Simon Ware, Adele Warlow, Alan Weyer, Mark White, Jo Whitford, Aaron Wolf, Tom Wolfe, David Wood, Martin Wood, Tony Yeo.

Personally: Ann Allsop, Arvid Anderson, Maynard Atik, the Banners, Pete Barnes, Alison Bent, Hilary and Robert Bruce, Jon Burke, John Bush, Lincoln Callaghan, Don Carson, Pat Champion, Hunter Chatriand, Cocina, Common Ground, John Cottrell-Dormer, Tim Cox, Celia Culpan, Deb K. Das, the Davenport, the Deanes, Mark Demos, Monty Dennison, the Dowdall family, Emerald Downs, John and Barbara Dungee, Bob Dylan, Rev. Joanne Engquist, John Engstrom, Explorer West, Malcolm Galfe, the Gay Hussar, Colleen Graffy, Tom Graveney, Jeff Griffin, Grumbles, Masood Halim, the late Marvin Hamlisch, Hemispheres, the late Judy Hentz, Alastair Hignell, Charles Hillman, the late Amy Hofstetter, Alex Holmes, Hotel Vancouver, Jo Jacobius, the Jamiesons, Lincoln Kamell, the Keelings, Aslam Khan, Scott Kramer, KSA, Terry Lambert, Belinda Lawson, the late Borghild Lee, Todd Linse, Cherry Liu, the Lorimers, Rusty MacLean, the Macris, George Madsen, Lee Mattson, Chip Maxson, Les McBride, Jim and Rana Meyersahm, Missoula Doubletree, Sheila Mohn, Bertie Morgan, the Morgans, John and Colleen Murray, Jonathan Naumann, Chuck Ogmund, Larry Olsen, Phil Oppenheim, Pacific Rim Hotel Vancouver, Valya Page, Michael Palmer, Robin Parish, Peter Perchard, Greg Phillips, Chris Pickrell, PNB, Roman Polanski, the Prins family, Renton Coin Shop, Dean Richardson, Ailsa Rushbrooke, Debbie Saks, Sam, my father the late Sefton Sandford, Sue Sandford, Peter Scaramanga, Seattle Symphony, John Shepherd, the Sheriff family, the late Cat Sinclair, Fred and Cindy Smith, Rev. and Mrs Harry Smith, Debbie Standish, Lill Stanley, my friend the late Ted Stanley, Thaddeus Stuart, Jack Surendranath, the Taylors, TEW, Mandolyna Theodoracopulos, Diana Turner, Ben and Mary Tyvand, William Underhill, Diana Villar, Ross Viner, Tony Vinter, Lisbeth Vogl, John and Mary Wainwright, Neill Warfield, the late Chris West, Richard Wigmore, Willis Fleming family, Rusty Zainoulline.

And, as always, a low bow to Karen and Nicholas Sandford.

C.S.

2014

1

GOLDEN AGE

MCC’s seventh tour of South Africa started like an elaborate costume drama. The teams took the field on Saturday 8 November 1913 at the then haphazardly rustic Newlands ground in Cape Town accompanied by a brass band, a welcoming speech by the city’s mayor, and a crowd of 3,000 spectators in ‘loud stripes and voluminous summer dresses’. The local Weekend Argus generously described the visitors as being ‘as good a side as ever left England’. Nine of the fourteen tourists were veterans of the successful campaign to Australia of 1911/12, also led by the boxing cricketer Johnny Douglas of Essex, and they completed their strength with the young Surrey amateur Morice Bird, notable for having once scored two hundreds for Harrow in their annual clash at Lord’s against Eton; Lionel Tennyson, the poet’s grandson, who appeared for Eton in the same tie, if with rather less success; the Norfolk and Sussex all-rounder Albert Relf, a sound man in a crisis; and the Yorkshireman Major Booth, good enough to have scored over 1,000 runs and taken 158 wickets in the previous English summer, whose forename was to prove somewhat confusing when he went on to join the army as a 2nd lieutenant. According to the Argus, ‘the Englishmen as a whole appeared robust to the point of invincible on the Cape’, whereas the home team had struck a lean period ‘with a host of run-getters, but not much to offer in the field’. After a lacklustre opening performance at Cape Town, the tourists duly won all three of the first four Tests that were completed, before appearing for the final international game at Port Elizabeth which ran from 27 February to 3 March 1914. In the event, it was to be the last Test match involving England’s cricketers for nearly seven years.

They won comfortably there, too. It has been rated as good an all-round England side as would appear anywhere again until the 1950s, and is worth giving in batting order: J.B. Hobbs, W. Rhodes, H. Strudwick (wkt), J.W. Hearne, C.P. Mead, F.E. Woolley, J.W.H.T. Douglas (capt), L.H. Tennyson, M.C. Bird, M.W. Booth, A.C. Relf. Major Booth got his chance only because the great fast-medium bowler and contrarian Sydney Barnes, who was 37, pulled out due to a financial disagreement. He would not represent England again. In the four Tests he did play in South Africa Barnes took 49 wickets, which was only one fewer than all the eight other England bowlers used in the series. Despite the tourists’ victory at Port Elizabeth, the Argus reported that the last day’s crowd was ‘convivial’, watching the comings and goings of their batsmen with equanimity, and ‘filling the blanks in the play with their own humanity … there was frequent laughter around the refreshment tent when a spectator there scored a repartee’. When South Africa’s Reggie Hands, one of three cricket-playing brothers and a former England rugby international, got a wide long-hop from Douglas, he stepped back and shaped to make a full-blooded shot for a certain four to square leg. But not so. Somehow Hands completely misjudged the line of the ball, lost his balance, and fell to earth flat on his chest. Strudwick, the England keeper, made about 5 yards in a shallow dive worthy of the Olympic pool, and still had time to right himself and remove the bails while the batsman remained hors de combat. This ‘brought a fresh round of satirical comment from among the crowd’, wrote the Argus. ‘They accepted the inevitable, and fast ensuing, loss of the Test in excellent heart.’

There was an equally happy informality about the party later that evening for both sets of players and their guests. Before dinner, the cricketers mingled with the state prime minister Louis Botha. Grasping the England captain by the arm and alluding to his former career as an Olympic middleweight boxing champion, the premier said, ‘Well, it’s another knockout blow, Mr Douglas. I heartily congratulate you. The only difference is that your victims here can at least walk away unassisted.’ Douglas remembered being charmed by the humour and generosity of this little exchange, and of his South African hosts in general. ‘It was the tour of everybody who played in it’, he wrote. ‘Victor and vanquished emerged with equal honour; and the chief laurel crowned the game of cricket itself.’

It is worth dwelling on that particular Test at Port Elizabeth for a moment, if only to see what happened to some of its participants over the next five years. Within a month of the outbreak of war in August 1914, three of England’s batsmen, Hobbs, Rhodes and Strudwick, were employed full- or part-time in munitions factories; Hearne and Woolley both served in civilian posts and continued to play cricket in the Bradford League, where they would occasionally encounter Sydney Barnes, who would appear there well into his sixties; Charles ‘Phil’ Mead was apparently excused active duty, suffering from varicose veins and other medical issues; and Morice Bird fought bravely at Gallipoli, where he contracted amoebic dysentery, later emerging after the war as coach of Harrow, his old school, before his early death at the age of 45.

Moving down the England batting order, some of the players fared better than others. One or two of their lives, much like the times, often proved unhappy, macabre, turbulent, impoverished and plain bleak. On 23 July 1914, 24-year-old Lionel Tennyson was part of the Hampshire side starting a three-day match against Surrey at the United Services ground in Portsmouth. It was a day of ‘listless inactivity’, both on and off the field, the city’s Evening News reported. Surrey, the County Championship leaders, eventually won the match by 8 wickets with two sessions to spare. Tennyson, a serving soldier, elected not to appear in his side’s next match, against Essex at Leyton, which ended in a draw on the evening of Saturday 1 August. Heavy rain then set in. Two nights later, on the bank holiday Monday, Tennyson went to bed in his London flat and dreamed he was scoring a match-winning century for his county. ‘Although I acknowledged the applause in the orthodox fashion,’ he wrote, ‘it refused to stop.’ Gradually Tennyson realised that his dream was over and that the noise he heard was that of the night porter banging on the door, announcing he had a telegram to deliver. It was from his regiment, urgently recalling him to base ‘in light of the current situation’. Tennyson left his flat and reported back to barracks in Colchester at eight o’clock that morning. Three weeks later he was in the bloody retreat from Mons; twice Mentioned in Dispatches and three times wounded, he survived the war and eventually returned to captain Hampshire and England.

Major Booth, the sometimes brilliant batsman and wily swing bowler who took 4-49 to finish off the South African batting in the Test at Port Elizabeth, immediately joined the army on the outbreak of war. After serving as a sergeant with the West Yorkshire regiment in the Egyptian campaign, he was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant and sent to the Western Front. He was killed by shell fire on 1 July 1916, at the age of 29, after going over the top on the first day of the Somme offensive.

Johnny Douglas, the England captain in South Africa, also volunteered on the outbreak of war. Behind his muscular and occasionally arrogant presence on the cricket field it was thought that there lay a more complex, often misunderstood character. ‘Johnny never spared himself and did everything for the team’, his colleague Percy Fender once said. ‘Any problems arose because he seldom appreciated that others weren’t necessarily as physically or mentally hard as he was.’ Douglas survived the war and returned to civilian life to play another eleven Tests. On 19 December 1930 he drowned when the SS Oberon, on which he and some of his family were travelling, collided with another ship in heavy fog off the coast of Denmark. According to evidence given at the enquiry, Douglas perished while trying to save his elderly father.

Perhaps the most poignant fate of any of Douglas’s pre-war team was that of the veteran all-rounder Albert Relf, who was good enough to take 1,897 first-class wickets and score 22,238 runs in a 16-year career for Sussex and England. As a batsman, Relf may not have been the most dynamic of stroke-players, but this was offset by his stout defence, his determination, and his ability to improvise in tight situations. ‘No one seeing him for the first time would suppose him capable of getting his hundred in top company’, said Wisden. ‘He has a way of letting the ball hit the bat that is certainly not impressive to the eye. Still, the fact remains that season after season he makes as many runs as men who look twice as good as he is.’ After the war, this seemingly unflappable character took a job as cricket coach at Wellington College. Apparently depressed about money and the state of his wife’s health following a gallstone operation, Relf walked out to the school’s First XI pavilion on a stormy Good Friday morning in March 1937, locked the door, braced a shotgun against his heart and pulled the trigger. His wife later made a full recovery and came in to a considerable inheritance. Relf was 62 years old.

III

In March 1921, the British War Office published ‘final and corrected’ figures listing a total of 573,507 UK servicemen killed in action from 4 August 1914 to 30 September 1919; 254,176 were classified as ‘missing’ in the same period, less 154,308 released prisoners, for a net total of 673,375 dead or unaccounted for. There were 1,643,469 individuals described as ‘wounded or otherwise affected’ in the same report. Other estimates have suggested that there were some 744,700 British combat deaths, out of roughly 6,211,500 total enlistments. The real number will never be accurately known.

By averaging the above sets of statistics, it is possible to say that the chance of a British serviceman losing his life during the First World War was between 10.8 per cent and 11.9 per cent, or roughly one in nine. Although less catastrophic than sometimes thought, these are sobering figures: it’s widely agreed, for instance, that the UK suffered some 383,000 and 67,000 military and civilian deaths respectively in the Second World War, which lasted nearly six years. In purely statistical terms, the loss of Major Booth at the Somme might be said to show that the England cricket team suffered broadly the same casualty rate as for the British armed forces as a whole. If Lionel Tennyson had also died of his wounds, someone might be theorising that Test cricketers were twice as badly affected as the norm and would thus write about the tendency of red-blooded sportsmen to throw themselves in harm’s way when the situation arose. It is surely enough to repeat that cricket is a reflection of life, and that the mixed motives and varying fortunes of Johnny Douglas’s last pre-war side show that his players had their share of humanising contradictions, just like the rest of us. Clearly there were those who enlisted out of high-minded duty, and others who welcomed the call to arms for more personal reasons. To some, at least, the armed forces represented a refuge where the failed, felonious or fed up could simply go to disappear. Lionel Tennyson seemed to allude to this trend when he later wrote of the droves of ‘poor, smashed-up, timid little men’ queuing outside the door of a London recruiting station. A cricketer-soldier named Ian Hay said that ‘war is hell, and all that, but it has a good deal to recommend it. It wipes out all the small nuisances of peace-time’. Personal ambition was just as much the animating spirit of those young volunteers as of the sportsman judging the fine balance of his own performance against that of the team. The role of cricket in war makes such a fitting study precisely because most cricketers met the challenge the same as everyone else did, no better and no worse. There were fierce attachments to the patriotic cause, and there was also a good deal of bemused indignation that the country had somehow got itself in this mess in the first place.

Before leaving the world of cold statistics, we might also note that when England resumed playing international cricket in December 1920, against Australia, their team contained no fewer than six of the men who had appeared in that final pre-war game at Port Elizabeth, which would be to confer a flattering degree of consistency if applied to a modern English representative side. More significantly, three of the South African XI in that last Test also died in the war. The all-rounder Claude Newberry fell in the Somme campaign on 1 August 1916, aged 27; the seam bowler Eric ‘Bill’ Lundie was killed at Passchendaele in September 1917, aged 29, having played his first and only Test in Port Elizabeth; and the double-international Reginald Hands succumbed to wounds suffered on the Western Front in April 1918, also aged 29. Reggie Schwarz, another cricket-rugby international, played for South Africa twenty times between 1905 and 1912. He served in the King’s Royal Rifle Corps throughout the war, winning the Military Cross, and survived the trenches only to fall victim to the worldwide Spanish flu epidemic on 18 November 1918, just a week after the Armistice, aged 43.

III

When the historians and sociologists came to look back on the events of August 1914, some of them made a rather tenuous case about the self-destructive nature of British culture, or society as a whole, as if the nation had somehow been engaged in a headlong communal death wish. Without going overboard, we can perhaps say that it was one of those eras when a precociously talented artistic elite seeks to subvert the consensus mood and disconcert its audience. By June 1914, for example, the touring Imperial Russian Ballet was all the rage at London’s Covent Garden. The company’s latest production, Légende de Joseph, took place on a set decked out in pink marble, with towering pineapple-shaped gold columns and a cast dressed largely in yellow silk, attended by a host of sparsely clad Moorish slaves and two Russian wolfhounds in sparkling diamante collars. As a result, a certain theatricality began to creep into London society dress and furnishings. For the more rhythmically minded, meanwhile, there was Hullo Rag-time!, a song-and-dance revue that ran for nearly 500 performances in 1913–14. Essentially, this was an excuse for wailing young women to high-kick in dresses of a singularly sparing cut, while a line of bongo drummers went into a syncopated frenzy. Some saw it all as a profound indictment of cultural vacuity – others found vacuity in the performance itself. To the 19-year-old cricket-playing author J.B. Priestley, the show was all about ‘progressiveness and dislocation’ in British society.

For those who like to see some higher societal meaning in the arts, there was also Vorticism, an aggressively modernist movement under the loose direction of the 29-year-old painter and author Wyndham Lewis, headquartered at the unambiguously named Rebel Art Centre in central London. The Times described the work displayed there as ‘not so much pictures as theories illustrated in paint’. In July 1914, the Vorticists provoked an unusually heated critical debate when they staged an exhibition of ‘angular abstractions’. At what proved to be the show’s opening and closing night, there were reports of fist fights both among the audience, and between the audience and the police, and one well-dressed patron is said to have climbed an avant-garde rendering of the Statue of Liberty and then swung, ape-like, from a black chandelier. In later years, Lewis insisted that he had repeatedly flicked the gallery’s lights on and off in a strobe-like effect, hoping this would put a stop to the fracas. The accounts are as varied and confused as the scenes they claim to describe, and the only certainty is that the Vorticists disbanded shortly afterwards, and that Lewis himself went on to serve with distinction on the Western Front as an artillery officer and war artist.

Disillusion with the past and an apparent impatience to destroy the last vestiges of Victorianism were not the only background factors said to have set British society on the road to war: ‘roar[ing] for its own death,’ in one contemporary account. Others have claimed that there was something about English sport in general, and cricket in particular, that lent itself to the fatally jingoistic mood of August 1914. In most teams, Priestley theorised, there was a certain ‘dogged and implacable devotion to the higher cause … a disinclination to upend authority’. ‘We were all romantics’, said Ulric Nisbet, a 17-year-old member of the Marlborough XI, who went off to war instead of finishing his last year at school. ‘With us the attitude was “Theirs not to reason why.” There was no tennis at Marlborough, for example. That was too individual: the public school was a team.’ The diaries and letters of many first-class cricketers who served at the front speak of ‘the great game’, the ‘wonderful feeling of fellowship’, the ‘exhilaration’ of fighting alongside one’s friends and comrades. At the beginning of the war, many enlisted in groups in order to form their own cricketing sub-battalions. A widow named Judith Flanders looked out on a dusty field in Carshalton, Surrey, one morning in September 1914 and saw rows of men marching off to camp in ‘blazers, straw hats and striped caps, some of them swinging a bat over their shoulders. They were singing and joking all the way.’ Cricketer psychologists such as Mike Brearley have speculated that the game’s essential structure of long periods of tedium, punctuated by sudden bursts of drama or controlled chaos (and, for the departed batsman, oblivion), might serve as a metaphor of some sort for military life.

Of course it is just as likely that the roughly 4,000 cricketers and officials of all standards around the world who signed up and died for their country in the First World War did so for the same quietly heroic reasons as everyone else. Sergeant Colin ‘Charlie’ Blythe, of Kent and England, was 38 when he was killed by shell fire on the railway line outside Passchendaele on 8 November 1917. A fellow serviceman who survived the war wrote: ‘we remember his cheerfulness, his keen sense of joy and devotion, even in the most arduous circumstances, and the brave deeds he performed daily without any hesitation or comment on his part.’ Despite his epilepsy, Blythe both played the violin and perhaps more importantly took 2,503 first-class wickets, 100 of them in Tests, with his slow-to-medium left-arm spin. Some opposing batsmen also attributed his success to a marked volatility and aggression. C.B. Fry thought him to be ‘the classic case of a fast bowler’s mind trapped inside a slow bowler’s body’. A monument erected to Blythe and other Kent players at the entrance to the St Lawrence ground in Canterbury says: ‘He was unsurpassed among the famous bowlers of the period and beloved by his fellow cricketers.’

Shortly after arriving with his unit at Passchendaele, Blythe remarked on the once-idyllic landscape which had been beaten into a sea of mud and rubble torn up by the German artillery. ‘There is no part of the human body I haven’t seen damaged or blown to pieces’, he wrote. To add a personal sense of loss, his younger brother Sidney had been killed in the fighting at the Somme just over a year earlier. At one time in October 1917, Blythe and his battalion had passed over the spot of Sidney’s death. That was ‘bad enough’, he admitted, and soon hunger added to the men’s misery. By early November, they had outrun their supply lines which were disrupted by German air attacks and were effectively living off the land, such as it was. The older Blythe seems to have had no illusions about the nature of war. His commanding officer later wrote that ‘he did not think it was a glorious affair, or that the English inevitably won. For him, there was nothing romantic about suffering, as there was for some of the society-warriors, but he maintained a buoyant note. What he most wanted was to do his job and to serve his fellow brothers-in-arms.’ Like most front-line soldiers, Colin Blythe looked at the war from the narrow circle of his own unit. In his letters authority is portrayed as stubborn or obtuse, while all around him were ‘the finest stock’, ‘the best fighters in the world’, with ‘no swank or bounce’ about them – ‘the men you would lay down your life for’.

III

It is often said the outbreak of the First World War brought an end to a golden age of English cricket. Even professional matches had a certain country-house flavour to them that was conspicuously gone by 1919. A modern county cricketer would hardly recognise the packed grounds on which his counterpart played a hundred years ago, seemingly as part of an extended Georgian garden party, with gaudily clad spectators, and often their servants and pets, too, camped out around the boundary. A finely tuned social etiquette prevailed among the little groups who darted to and fro between overs, like shoals of tropical fish. In general terms, the game combined a colourful splash of summer pastels with an intensity of support that worried the anonymous correspondent of Cricket magazine: ‘I do think sometimes that the Kent crowd is just a little too much wrapped up in Kent’s doings’, he wrote.

Technically, of course, cricket had its shortcomings. With a few notable exceptions, the batting tended to be rustic, the man who could ‘bowl a bit’ was in vogue, the fielding wasn’t great, and many county pitches were rudimentary at best. ‘The sport is, like the music-hall, truly an all-round entertainment’, a Times critic wrote in 1914. ‘There is a peculiar fascination about watching the many-striped stars gently exercise among rolling green fields and bucolic extras.’ Some rural grounds were all but indistinguishable from the neighbouring farms. At Taunton, a stray pig quite often wandered out from the ring of spectators to visit the square. But it would be wrong to portray the pre-war County Championship as merely a case of effete young men in cravats behaving as if they had stepped out of the pages of a P.G. Wodehouse book. There was little of the Corinthian spirit about Colin Blythe, for one. Born in Deptford in 1879, Blythe left school at 12 and applied for a county trial largely as a way to avoid working alongside his father as a fitter. He took a wicket with his first ball in first-class cricket, and resolved then and there to make it his career. As he began an over, the thin and lantern-jawed Blythe would sometimes work himself into a state approaching hatred for the batsman he was about to bowl to. If they watched closely enough, his teammates could hear him muttering to himself and see him clenching his jaw. There was once some protracted controversy when C.B. Fry, batting for Hampshire, objected to Blythe deliberately bowling full-tosses to him in such a way that the ball was completely lost in the sun. This was a rare occasion when the batsman complained about the light being too good. Blythe’s story is not one of schoolboy romance but of a professional sportsman who asked, and gave, no quarter.*

On the morning of 6 May 1914 the Hampshire players took the field for their opening match of the season, against Leicestershire at Southampton. Reporting on the match, The Times was rhapsodic: ‘it [was] all a voyage of the most joyous anticipation, played out among lush hills, blue skies and glistening fresh paint upon the pavilion railings.’ However often stated, there is a poignancy to the idea of so many young men going straight from the pastoral world of English cricket to the horrific scenes of carnage that awaited them on the battlegrounds of northern France. Three months later, fourteen of the twenty-two players at Southampton would actively participate in the war. Hampshire’s demon fast bowler Arthur Jaques, one of the few first-class cricketers born in China, fell at the Battle of Loos in September 1915. Leicestershire’s opening batsman Harold Wright divided his time between playing cricket and managing his family’s elastic webbing factory in Quorn. In July 1914 Wright was commissioned as a captain with the 6th Loyal North Lancashires, and twelve months later took part in the sustained attack at Gallipoli, where he was severely wounded. Refusing medical treatment, he continued to fire at the enemy lines until eventually losing consciousness. Evacuated back to England, Harold Wright died there from his wounds on 14 September 1915, at the age of 31. Several of his letters home write of the ‘adventure’ of war, and of a zeal for the ‘good fight’ as a whole. This quality of enthusiasm might seem eccentric to our more cynical age. Wright’s generation was the first to fly, to travel in cars, to see films and to hear disembodied voices coming to them over the radio. Perhaps it is not surprising so many of them retained a sense of wonder even in the most trying circumstances.

At around the time the young Harold Wright was setting new batting records at Mill Hill school, a boyish and still only modestly successful middle-aged Scottish author named James Barrie was assembling his own touring cricket side. Born in 1860, the short and moustachioed Barrie would go on to some acclaim with Peter Pan, but was chiefly known at the time for a series of locally popular novels of parochial Scotland, as well as a play about the eighteenth-century poet Richard Savage which had closed after one matinee performance. As soon as he announced he was raising a team, Barrie was deluged with applications by players not only from Britain but all over Europe. The side’s first fixture did not bode well for this cosmopolitan line-up: one French playwright turned up wearing pyjamas, a colleague extended the idea by falling asleep in the outfield, while a third man, a Belgian, thought that the game had finished every time the umpire called ‘Over’. Barrie’s men managed a total of just 11 runs on that occasion. The writers Arthur Conan Doyle, Willie Hornung, A.A. Milne and P.G. Wodehouse, of Sherlock Holmes, Raffles, Winnie the Pooh and Jeeves fame respectively, all turned out for the side over the years. Since Barrie himself went on to produce The Admirable Crichton, members of his eleven would be responsible for creating English fiction’s two most famous valets. Conan Doyle once achieved the unusual distinction of managing to set himself on fire when batting. A ball struck him on the outside of the thigh and ignited the box of matches he kept in his pocket. After experimenting with various alliterative nicknames – Jingo Jim’s, Bards and Barbarians, the Tartan Terrors and so on – the team eventually called themselves the ‘Allahakbarries’, which they translated as ‘God help us.’

When the war came, the Allahakbarries suffered as much as everyone else. Guy du Maurier, a soldier-author who wrote a patriotic play called An Englishman’s Home, fell at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle in March 1915. Barrie added the graphic detail that his friend had ‘wandered around the battlefield for half-an-hour with his stomach hanging out, begging somebody to finish him off’. Following the death of their parents, du Maurier had become the co-guardian of his five Llewelyn Davies nephews, who served as the inspiration for Peter Pan. Barrie wrote to George Llewelyn Davies, who was in France with the Rifle Brigade, to inform him of Guy’s death; by the time Barrie received his reply, George himself had been killed; he was 21. George’s younger brother Peter fought at the Somme, and was invalided home after six weeks suffering from shell-shock. He later returned to the front and won the Military Cross. Four regular members of the Allahakbarries side, including Conan Doyle, lost a son in the war. The emotional scars affected Barrie for the rest of his life. ‘The war has done at least one big thing’, he said early in 1919, ‘it has taken spring out of the year.’ The Allahakbarries never played as a team again, though there was a brief but poignant revival in 1922 when Barrie, in a tweed suit and homburg, picked up a cricket ball and bowled it to Field Marshal Haig, the British commander at the Somme, who faced it in full military uniform. The author bowled him out. Barrie died in 1937 and Peter Llewelyn Davies committed suicide in 1960, aged 63.

III

Over the August bank holiday of 1914, coastal England teemed with men and women sporting a variety of decorous bloomers and modest dark-toned stockings who still bathed in separate preserves; couples parading on the front arm-in-arm was the limit of a public show of affection. Brighton and the other resorts had rarely been as full as they were that weekend. Elsewhere in England, there was a busy programme of summer sport. The annual Henley Regatta had wound up on 5 July, with record crowds enjoying the ‘grilling hot’ days of Renoir-like display, though its general mood of ostentation lingered: thanks to the Anglo-American Exposition, there were an estimated 80,000 tourists from across the Atlantic in London, which saw a full-scale baseball game played at Holland Park and nightly fireworks over Westminster. According to the Daily Mirror, American women preferred ‘white canvas boots and suits of fine blue serge’, and were easily recognisable by the battery-operated fans many carried while en route to their dates at ‘the air-cooled Cecil Hotel, or the new-fangled soda-fountain in the Strand’. Among those the crowds had come to see at Henley was the chisel-jawed Australian Frederick Kelly. By all accounts, this ‘beautifully rugged specimen’, as The Lady called him, was one of those Renaissance men to whom nature runs riot in its gifts. Having won a chestful of medals as an oarsman, he turned to the running-track, ‘where he was as fleet as a greyhound’, and also played competitive tennis, golf and polo. Away from the sports field, Kelly was an accomplished classical pianist and composer, and once conducted a programme of his work to a full house at London’s Wigmore Hall. He immediately joined a detachment of the Marines on the outbreak of war, won the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC), and died in November 1916, aged 35, while leading an attack on a German machine-gun emplacement at the Somme.

Meanwhile, the Jersey golfer Harry Vardon won the sixth and last of his British Open championships, amid scenes which again contained as much blazered pageantry as raw sport. Vardon volunteered to fight on the outbreak of war, when he was 44, but was found to be suffering from tuberculosis. North of the border, the Hearts football team finished the Scottish season in some style, with a run of eight successive wins. On the same day at the end of the season, every member of the side joined the British army. Three of the eleven, Harry Wattie, Duncan Currie and Ernie Ellis, were killed on the first morning of the Somme offensive. A colleague, Paddy Crossan, survived the war but later died, aged 39, his lungs all but destroyed by poison gas.

At Wimbledon, Norman Brookes of Australia won the men’s singles final against New Zealand’s Tony Wilding, holder of the title for the previous four years. Wilding had also appeared as an all-rounder in first-class cricket for Canterbury. On the outbreak of war he joined the Royal Marines, and was killed during an attack on enemy sniper positions at Neuve Chapelle in May 1915 at the age of 31. The popular German champion Otto Froitzheim went straight from Wimbledon to take part in an international challenge cup in the United States. War was declared halfway through his first match. Froitzheim sailed home to enlist, but his boat was detained by a Royal Navy patrol and he was taken into custody in Gibraltar. As the war continued, many of the non-combatant German POWs were transferred to England. As a result, Froitzheim spent the next four years in an internment camp at Leigh-on-Sea, where he was regularly seen strolling on the front clad in a German tennis blazer and that town’s only pair of cerise trousers, chatting affably with the locals. Released in January 1919, he was briefly engaged to the filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl, and died in 1962, aged 78.

In cricket, everything changed and everything stayed the same. On the bank holiday Monday of 3 August, there was a crowd of 15,000 at the Oval to watch Jack Hobbs score 226 in just over four hours for Surrey against Nottinghamshire. Due to the weather, the match was drawn. Hobbs notes the event serenely in his autobiography: ‘I made [the runs], with never a thought of war.’ Late the following afternoon, as the British government delivered its note to Germany, signs were pasted up announcing that the Oval would be ‘commandeered for military purposes’ at the close of the match. On Wednesday morning, 5 August, the players and spectators returned to the ground to find themselves at war. It was raining. According to Wisden, the mood in the stands reflected a ‘notably less convivial’ atmosphere than had prevailed a day earlier. ‘After Surrey’s innings had been finished off, [Nottinghamshire’s] Gunn and Hardstaff stayed together for two hours. So bad was the “barracking” at times that several of the offenders were removed by the police.’

Canterbury cricket week opened to bright sunshine, and capacity crowds, with a hard-fought match between Kent and Sussex. Colin Blythe returned figures of 6-107 and 4-39, but by the time Sussex came to win with just twelve minutes left, said Wisden, the event was ‘shorn of most of its social functions’. Hospitality tents reserved for the East Kent regiment and other army units had been hurriedly deserted. At Old Trafford, the 37-year-old Lancashire captain Albert Hornby, son of the great ‘Monkey’ Hornby, was called from the field on the first morning of the annual Roses match against Yorkshire and rushed south to join his regiment. Although Hornby survived the war, his younger brothers John and Walter were wounded and killed respectively. Three of Hornby senior’s four sons predeceased him. Yorkshire’s captain in the match, Sir Archibald White, also left the field early in order to report to the War Office. Reggie Spooner, of Lancashire and England, soon followed them into the colours. Spooner was another of those prodigiously talented athletes, good enough to have played both rugby and cricket at international level. He cut a dashing figure. Six feet 2in tall and superbly lithe, he wore immaculately tailored suits and gave one royal admirer ‘the appearance of strutting even when sitting down’. It was said that no one played the cover drive better than he did until Walter Hammond appeared on the scene. Captain Spooner saw action with the Lincolnshire regiment, but was invalided home after being wounded at Mons. He played only a few more times after the war, though he lived to be 80. Both Pelham Warner and Arthur Carr, captain of Middlesex and Notts respectively, abandoned cricket after being called away by the authorities.

III

Early death is frequently seen as a sort of martyrdom. Individual deaths are often depicted that way, with whole news broadcasts devoted to covering the funeral of, say, a self-destructive, middle-aged showbusiness celebrity, and it is possible much the same thing applies to an era that ends abruptly or violently. So it might be best to approach the ‘golden age’ of cricket with caution. The 1890–1914 period certainly contained its fair share of acknowledged giants of the game such as Grace, Trumper, Hobbs, Barnes, Ranjitsinhji, Woolley and Foster. During the same era, Test cricket and representative tours both acquired something close to their modern structure. England and Australia played each other in fifteen series during those years, with England narrowly winning eight series to seven. Although it offered few of today’s limited-overs batting fireworks or terrier-like fielding (and as late as 1913 the MCC side was accompanied to South Africa by all of two pressmen, one an expert on bowls), the hard-fought and animated game of around the turn of the century was enormously popular with crowds in Britain and overseas. Stately-home cricket was at its peak and the public-school game enjoyed no fewer than eighty-four closely typed pages of coverage in the 1915 Wisden, which is roughly eighty-one more than it does today. The annual Oxford-Cambridge match at Lord’s remained one of the highlights of the London social season. Add a thriving series of northern leagues, a network of increasingly well-organised clubs and villages, and private teams such as Barrie’s travelling the length and breadth of the country each weekend, and it is clear cricket was not only the dominant English sport, but one of the nation’s defining themes.

Of course, it is also possible that we tend to idealise the age precisely because it finished as suddenly and brutally as it did. Even after a second great conflict loomed and the Great War had become known as the First World War, the events of 1914–18 were seen as the end of an age of innocence, the end of a way of life identified with the nineteenth century, and a transition to the age of modernity. For decades, the phrase before the war meant ‘before 1914’, and the words carried echoes of a time that was lost forever. Defining social eras is always a risky business, and often owes more to nostalgia than to dry historical facts. The cricket writer David Frith alludes to this when he talks of the ‘soft, romantic shafts of museum lighting’ that can retrospectively colour our judgement of certain periods of the game. It’s difficult to write objectively of a group of young sportsmen knowing that so many of them will go on to die in action, be wounded, or come home with mental scars that will never heal. The war gave a whole generation deep and well-justified reasons to be sceptical about the wisdom of political and social leadership, and that scepticism of authority spilled over even into cricket, which never quite regained its air of magnificently feudal charm on its return to England in May 1919.

Although the war and its aftermath necessarily chastened the cricket world, not everything about the pre-1914 game was of utopian innocence, or everything post-1918 of cynical self-interest. Just to put some perspective on it, we find the great Victorian W.G. Grace, in 1895, concerned that cricket had become ‘too much of a business like football’ – perhaps ironically, from a man as famous for his robust financial negotiating as for his batting. When Grace agreed to captain the MCC side to Australia in 1891/92, he did so only after securing a personal fee of £3,000 (a county professional – or ‘professor’ – of the day might earn as much as £150 a year, but he did so without job security or a pension, and in the knowledge that he faced a likely ignominious exit in his mid-thirties, which was not quite the same thing). Grace’s successor as England captain, Andrew Stoddart, angrily withdrew from a home Test against Australia in 1896 after the Morning Leader ran an editorial attack on him for his practice of demanding ‘extortionate’ performance bonuses. No fewer than five England players in the same match threatened to take strike action unless they were paid twice their normal fee. Clearly, too, not everything was relentless swashbuckling on the field of play. One correspondent’s recollection of the Nottingham Test that year was of ‘hour after hour of the backward-defensive stroke, of cricket as dour and grey as the smoke going up straight from the chimneys beside the Trent’.

The idea that Britain itself was an unmitigated social paradise in the years before 1914 also needs correction. Apart from the Irish Question, the trade unions were up in arms, conditions in many factories had changed little from Dickens’s day, and for large numbers of working-class children malnutrition was the rule and adequate food and shelter the exception. In one Birmingham suburb, it was reported, the local state school ‘did not satisfy the most basic educational or even sanitary requirements’, while even in more affluent mid-Sussex the Express newspaper deplored the number of ‘stunted-looking youths with some debility, and the pallor of anemia’. The life expectancy for a British male was 46. These facts do not exactly suggest a Garden of Eden before the Fall. Meanwhile, the suffragette movement was beginning to make itself heard by the smashing of shop windows, the holding of rallies, and the periodic invasion of golf tournaments and race meetings. One correspondent of Cricket magazine was worried that the ‘vandals’ would desecrate the most hallowed turf of all:

Are the authorities at Lord’s taking heed of the latest aspect of the ‘monstrous regiment of women’, with a view to protecting their sacred charges? After the golf greens, surely the cricket grounds in their due season? And that will be a matter of vastly larger import to the main body of the community.

Still, for a cricketer it was a good life while it lasted. A professional like Colin Blythe, who was married with several dependent relatives, must have enjoyed the opportunity to escape a hard and monotonous career in a factory and instead be paid for doing what he loved, earning not only a fixed salary but a cash bonus of 2 guineas for each first-class wicket he took over a total of 80. He managed 167 in the 1913 season and 159 in 1914. As well as county and Test cricket, Blythe was invited to regular country-house matches, like the one he played at Old Buckenham Hall in Norfolk in September 1913, where the owner, a socially ambitious Australian mining tycoon named Robinson, presented each of the players with a bag of six gold sovereigns, an engraved cigar case and a bottle of ‘dynamite-strength’ liqueur before leading them in to an elaborate banquet – ‘a marathon event with six courses, and topped off by an Australian brandy of such potency it was considered unwise to smoke in the same vicinity’. Blythe was also asked to play in the annual Gentlemen v. Players fixture at Scarborough at the beginning of a week-long festival, and finally in a ‘Kent and Yorkshire against The Rest’ match at the Oval, where he took only one wicket but enjoyed another ‘long and well-provisioned beano’ at London’s Strand Palace Hotel after stumps were drawn on 17 September. According to another of the players, Major Booth, everything went well enough at the dinner until someone asked someone else to pass the soup ‘and he airlined it’. Booth then went under the table, where he found George Hirst of Yorkshire and England. Someone bowled a series of bread rolls down the tile floor. Gilbert Jessop hit at least one of them with a hard-backed menu. Two policemen turned up, one of them a former MCC player named Rawson, whereupon ‘they proceeded to remove his helmet and use it as a receptacle’. A great deal of beer was also poured over Hirst’s head, and he remembered experiencing a ‘wavy feeling’ when rattling up in the train the next morning to Leeds. Shortly after all this, Blythe was able to enjoy a brief winter holiday in Chamonix in the French Alps, where he mingled with the likes of Arthur Conan Doyle, Count Betrand de Lesseps – son of the canal builder – and a resting German opera diva ‘among other prominent figures of the Arts’, before moving around France and various small towns on the Italian Riviera, eventually reporting back to Canterbury on 12 April 1914.

It was also an era when many first-class cricketers excelled at more than one sport. Andrew Stoddart was probably the leading English example of the Renaissance man who played Test cricket and international rugby, as well as being a founding member of what became both the British Lions and the Barbarians. He was the son of a Durham colliery owner who made himself into the beau ideal of a southern gentleman cricketer, and later used his considerable charm to help win (and then lose) large sums as a City stockbroker. Long before their 1914 ‘crisis of Europe’ tableau, Stoddart had his own waxwork effigy at Madame Tussaud’s. There were numerous other cases of the performer popularly acclaimed at two or more sports, including among others George Vernon, Reginald Hands, ‘Monkey’ Hornby, Sammy Woods, Richard Young, Cuthbert ‘Pinky’ Burnup, Reggie Schwarz and Frank Mitchell. Mitchell achieved the unusual distinction of winning a triple blue at Cambridge, before going on to play rugby for England and Test cricket for England and South Africa. An all-rounder in the fullest sense, Major Robert Poore played cricket for South Africa, Natal and Hampshire, interrupting his career only to serve with distinction on the away side in the Boer War. He also excelled at polo, golf, tennis, fencing and the blunderbuss. A genuine eccentric, in hot weather Poore fielded in a solar topee and once advised a terrified young colleague that the best way to play Harold Larwood was to ‘fix yer bayonets and charge ’im’.

Another versatile character was Lieutenant Cecil Abercrombie, who combined a brief but distinguished naval career with playing cricket for Hampshire, for whom he scored four centuries in his first and only full season, including one on his county debut, and rugby for the United Services and Scotland. Abercrombie ‘flashed his bat like a cavalry sword’, said the Gazette, rather mixing its armed forces. It was widely said that he hit the ball as hard as anyone in the history of cricket to then. On the outbreak of war, Lieutenant Abercrombie immediately rejoined his squadron at Portsmouth. On 31 May 1916 at 5.30 p.m. he was on the bridge of the armoured cruiser HMS Defence, sailing about 3 miles in advance of the main British fleet off Jutland. Emerging from the mist, a German battlecruiser and four dreadnoughts opened fire from a distance of 7,000 yards. The Defence was hit by two salvoes from the enemy ships that caused her aft magazine to explode. Within two minutes, the resulting fire had spread by way of the ammunition passages to the ship’s main magazines, which detonated in turn. There were no survivors among the 900-strong crew. Cecil Abercrombie had just celebrated his 30th birthday.

Abercrombie largely learned his cricket in the nets at Portsmouth, where he often practised with his friend Lionel Tennyson when both men were making their way into the Hampshire side. Because of injuries and military commitments they rarely had the chance actually to play together, and we can only speculate on how they might possibly have found themselves appearing alongside one another in the post-war England team, when they would have been in their early thirties. Tennyson missed much of the 1913 season largely because of army duties, but always remembered the Friday afternoon when he went to the county ground at Southampton to watch the cricket prior to driving ‘Uncle Cec’ up to London for a weekend house party.

The match was Hampshire v. Sussex in mid-August, and it was as good an example as any of the ‘quaint idyll’ ideal of cricket’s golden age. It began on one of those perfect late-summer mornings, with the local Gazette reporting that ‘thousands stood wilting under the heat to pay their admission of ninepence at the turnstiles, which clicked away busily’. Immediately next to the report of the match, the paper noted that the German Kaiser had spoken to journalists that week about settling his territorial ambitions with ‘blood and iron’. The visitors won the toss, batted, and made exactly 300. The opener Joe Vine hit a lightning-fast 75, often profitably exploring the aerial route over extra cover, and Vallance Jupp, coming in at number seven, added 50 not out. The Sussex side contained no fewer than three Relf brothers, as well as the 20-year-old Percy Fender, in his last season with the county before moving to Surrey. On this occasion, Fender, a mercurially talented and often eccentric cricketer whom a later critic felt had ‘prefigured Peter Sellers playing the part of Inspector Clouseau’, departed for a second-ball duck. The Gazette remarked that ‘the refreshment tent, which had emptied when “PGF” strode out to the crease, soon filled to capacity again’. Hampshire went in late on the first evening and scored 420, with Phil Mead contributing 100 at a run a minute. The bowling Relf brothers all came in for grief, though the youngest of the three, Ernest, eventually finished with creditable figures of 2-26. Fifty years later, Fender could still remember the subtle efforts of the Sussex bowlers not to catch their captain’s eye and become the next victim. Cecil Abercrombie then chipped in with what the paper called an ‘exquisite cameo’ of 37. At one stage, Fender himself bowled him what he remembered as a ‘really good fast-medium yorker on his leg stump’; Abercrombie killed the ball with a forward prod, ‘then looked up, courteously touched his cap and grinned: “Well bowled, Master”.’ Fender thought to himself, ‘He won’t expect another one’, so he repeated the performance. This time, Abercrombie took a half-step forward and deposited the ball over long-on, where it eventually landed in a mobile whelk stall. ‘He was a joy to watch unless you happened to be bowling to him’, said Fender, ruefully.